|

READING HALLTHE DOORS OF WISDOM |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ITALY AND HER INVADERS

BOOK I.THE VISIGOTHIC INVASION

CHAPTERSI. EARLY HISTORY OF THE GOTHSII. JOVIAN, PROCOPIUS, ATHANARICIII. VALENTINIAN THE FIRSTIV. THE LAST YEARS OF VALENS

V. THEODOSIUS AND FOEDERATI.VI. THE VICTORY OF NICAEAVII. THE FALL OF GRATIANVIII. MAXIMUS AND AMBROSEIX. THE INSURRECTION OF ANTIOCH.X. THEODOSIUS IN ITALY AND THE MASSACRE OF THESSALONICA.XI. EUGENIUS AND ARBOGAST.XII. INTERNAL ORGANISATION OF THE EMPIRE.XIII. HONORIUS, STILICHO, ALARIC.XIV. ARCADIUS.XV. ALARIC'S FIRST INVASION OF ITALY.XVI. THE FALL OF STILICHO.XVII. ALARIC’S THREE SIEGES OF ROME.XVIII. THE LOVERS OF PLACIDIA.XIX. PLACIDIA AUGUSTA.XX. SALVIAN ON THE DIVINE GOVERNMENT.

BOOK II.THE HUNNISH INVASION<I.

|

|

|

|

|

THOMAS HODGKIN

|

In the following pages I have endeavoured to meet the requirements of two

different classes of readers. For the sake of the general reader, who may not

have his Gibbon before him, nor a Latin Dictionary and Classical Atlas at his

elbow, I have taken for granted as little special knowledge of Roman history as

possible, I have generally kept the text clear of untranslated quotations, and

I have explained, with even tedious minuteness, the modern equivalents of

ancient geographical designations, and have sometimes used the modern name

only, at the cost of an obvious anachronism.

On the other hand, as I have proceeded with my work,

and become more and more interested in the study of my authorities, I have

begun to indulge the hope that I might number some historical scholars among my

audience. To these, accordingly, I have addressed myself almost exclusively in

the notes, whether at the foot of the page or at the end of the chapter; and

these notes, for the most part, the general reader may safely leave unstudied.

Should my book be fortunate enough to come into the hands of a scholar, he is

requested to pardon many an explanation of things to him trite and obvious,

which I should never have introduced had I been writing for scholars alone.

It will be observed that when sums of money are spoken

of, I have generally given the equivalent in sterling. This does not, however,

convey much information to the mind unless it be also stated what was the

“purchasing power” of a sum equivalent to a pound sterling in those days. I

would gladly have added a chapter on “The History of Prices under the Empire”

and had collected some materials for that purpose, but I feared to weary my

readers with a discussion which might have interested only a few. The general conclusion

at which the most careful modern enquirers seem to have arrived is thus stated

by Gibbon: about the year 470, the value of money appears to have been somewhat

higher than in the present age. The general rise of prices since Gibbon’s time

may justify us in making this statement somewhat stronger. It is probable that

in Imperial Rome £100 would have had about the same command over commodities

which £200 has in our own day. But of such enormous differences in value, when

measured by the precious metals, as exist between the England of Victoria and

the England of the Plantagenets there is here no question.

I have made a slight departure from precedent by

introducing more illustrations, than are usual in a work of this description.

The chief object of the chromo-lithographs of ecclesiastical edifices at

Ravenna is to convey to those who have not visited that place some idea of the

general effect of the Mosaics. They are engraved from drawings carefully made

on the spot by Mr. George Nattress. The coins here figured are, with one

exception, all in the British Museum. I am indebted to the kind assistance of

Mr. H. A. Grueber (in the coin department of that institution) for their

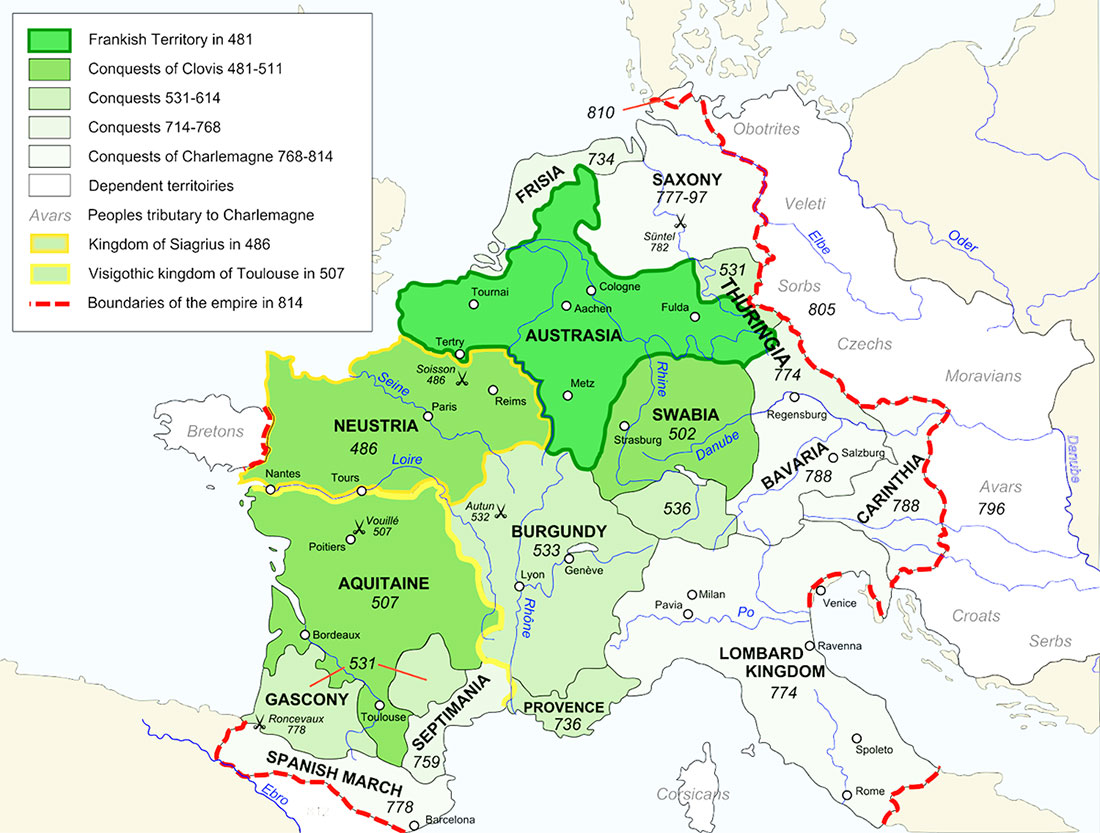

selection and arrangement. For the maps, though chiefly founded on Smith’s Classical

Atlas, I must be myself responsible. Some boundaries are conjecturally drawn,

but I have endeavoured to make this conjectural element as small as possible.

I take this opportunity to express my thanks to three

friends, with whom this book, which has given me six years of happy labour,

will always be connected in the mind of the author. My brother-in-law, Mr.

Justice Fry, first encouraged me to attempt such an undertaking, and the advice

of Dr. James Bryce and the Rev. M. Creighton was exceedingly helpful at a later

period of the work. My hearty thanks are also due to the Delegates of the

Clarendon Press, for undertaking the publication of the work of one who is a

stranger to the University of Oxford.

The volumes now published form a chapter of history which

is complete in itself; but if life and health be continued to me, I hope to

narrate hereafter the fortunes of the Ostrogoths and Lombards, and thus to

bring my work down within sight of the august figure of Charles the Great.

THOS. HODGKIN.

Benwelldene,

Newcastle-on-Tyne, 5th December, 1879.

|

|

|

|