|

READING HALLTHE DOORS OF WISDOM |

|

|

|

|||

ITALY AND HER INVADERS.BOOK VIII.

|

|

On the 18th of June, 740, died the great Iconoclast Emperor, Leo the

Third, after a reign of twenty-four years, marked by many great calamities, by

earthquake, pestilence and civil war, but also by legal reforms, by 7a fresh

bracing up of the energies of the state both for administration and for war, by

the repulse of a menacing attack of the Saracens on Constantinople, and by a

great victory over their army gained by the Emperor in person in the uplands of

Phrygia. Leo III was Emperor succeeded by his son Constantine V, to whom the

ecclesiastical writers of the image-worshipping party have affixed a foul

nickname, and whose memory they have assailed with even fiercer invective than

that of his father. He was undoubtedly a harsh and overbearing man, who carried

through his father's image-breaking policy with as little regard for the

consciences of those who differed from him as was shown by a Theodosius or a

Justinian, but he was also a brave soldier and an able ruler, one of the men

who by their rough vigour restored the fainting energies of the Byzantine

state. While he was absent in Asia Minor continuing his father's campaigns

against the Saracens, his brother-in-law, the Armenian Artavasdus,

grasped at the diadem, and by the help of the image worshipping party succeeded

in maintaining himself in power for nearly three years; but Constantine, who

had been at first obliged to fly for his life, received steadfast and loyal

support from the troops quartered in the Anatolic theme, and by their aid won

two decisive victories over his rival. After a short siege of Constantinople he

was again installed in the imperial palace, and celebrated his triumph by

chariot races in the Hippodrome, at which Artavasdus and his two sons, bound with chains, were exposed to the derision of the

populace. With this short interruption the reign of Constantine V lasted for

thirty-five years (740-775), a period during which memorable events were taking

place in Western Europe.

On the 10th of December, 741, Pope Gregory II died and was succeeded (as

has been already stated) by Zacharias, whose pontificate lasted for more than

ten years. The new Pope, like so many of his predecessors, was a Greek : in

fact, for some reason which it is not easy to discern, it was a rare thing at

this time for the bishop of Rome to be of Roman birth. Among the more important

events of his pontificate were those interviews with Liutprand at Terni (742)

and at Pavia (29 June, 743) which resulted in the surrender of the Lombard

conquests in Etruria, the Sabine territory, and the district round Ravenna, and

which have been fully described in an earlier volume. But far the most

important act of the papacy of Zacharias was that consent which near the close

of his life he gave to the change of the royal dynasty of the Franks, a

transaction which will form the subject of the following chapter.

Two months before this change in the wearer of the papal tiara had come

that vacancy in the office of the Frankish mayoralty which, as before stated

was caused by the death of Charles Martel at Carisiacum (October 21, 741).

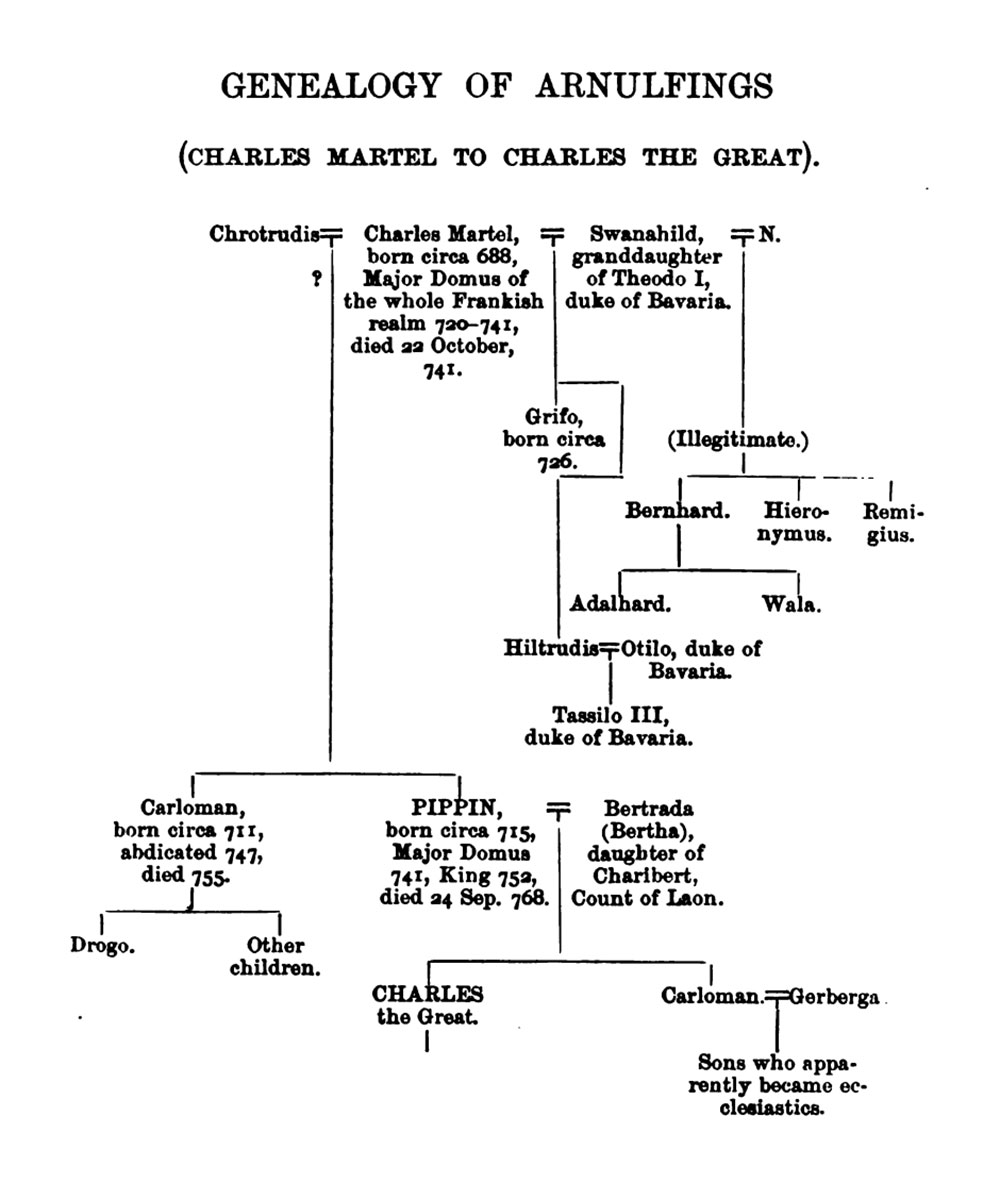

Two sons, Carloman and Pippin, the issue of his first marriage,

inherited the greater part of the vast states which were now practically

recognized as the dominions of the great Major Domus, who for the last four

years had been ruling without even the pretence of a Merovingian shadow-king

above him. Of these two young men, Carloman, the eldest, was probably about thirty,

Pippin about twenty-seven when they became possessed of supreme power by the

death of their father. As far as we can discern anything of their respective

characters from the scanty indications in the chronicles, Carloman seems to

have been the more impulsive and passionate, but perhaps also the more

generous, and, in the deeper sense of the word, the more religious of the two

brothers. Pippin seems to have been of calmer mood, clement and placable, a good friend to the Church, but also a man who

from beginning to end had a pretty keen sense of that which would make for his

own advantage in this world or the next.

In the division of the inheritance, Carloman, as the elder son, received

all the Austrasian lands, the stronghold of the Arnulfing family, together with Swabia and Thuringia. To Pippin fell as his share

Neustria, Burgundy, and the reconquered land of Provence. That Bavaria in the

east and Aquitaine in the west are omitted in the recital of this division is a

striking proof of the still half-independent condition of those broad

territories.

But besides several confessedly illegitimate sons of the late Major

Domus, there was one who both by his mother's almost royal birth and by the

fact of her marriage (possibly after his birth) to Charles Martel had some

claim, not altogether shadowy, to share in the inheritance. This was Grifo, son

of the Bavarian princess Swanahild, at the time of his father's death a lad of

about fifteen. Already during Charles Martel's lifetime Swanahild appears to

have played the part of a turbulent wife, and in league with Gairefrid, count of Paris, to have actually barred her

husband out of his Neustrian capital and appropriated some part of the revenues

of the great abbey of S. Denis. Either the turbulence of the rebellious or the

blandishments of the reconciled wife appear to have so far prevailed with the

dying Mayor of the Palace that he left to the young Grifo a principality in the

centre of his dominions carved out of the three contiguous states, Austrasia,

Neustria, and Burgundy. But almost immediately on Charles's death the discord

between Swanahild’s son and his brothers burst into a

flame. Whether Grifo took the initiative, occupied Laon by a coup de main, and

declared war on his brothers aiming at the exclusive possession of the whole

realm, or whether the Franks, hating Swanahild and her son, rose in armed

protest against this division of the realm and blockaded Grifo in his own city

of Laon, we cannot determine. In either case the result was the same : Laon

surrendered, Grifo was taken captive, and handed over to the custody of

Carloman, who for six years kept him a close prisoner at ‘the New Castle' near

the Ardennes. Swanahild was sent to the convent of Chelles,

where she probably ended her days.

A little more than two years after the death of Charles Martel, in

January, 744, his brother-in-law Liutprand, king of the Lombards, also departed

this life. The papal biographer who records the death of a wise and patriotic

king with unholy joy attributes it to the prayers of Pope Zacharias,

calumniating, as we may surely believe, that eminent pontiff, who had received

many favours from Liutprand, and who seems also to have been a man of kindlier

temper than many Popes, and still more than the Papal biographers.

On the death of Liutprand, his nephew and the partner of his throne,

Hildeprand, succeeded of course to the undivided sovereignty. That unhelpful

prince, however, whose whole career corresponded too closely with the ill omen

which marked his accession, was after little more than half a year dethroned by

his discontented subjects. In his stead Ratchis, the brave duke of Friuli, son

of Pemmo victor of the Sclovenic invaders and hero of

the fight at the bridge over the Metaurus, was chosen

king of the Lombards. His accession appears to have taken place in the latter

part of September, 744. What became of his dethroned rival we know not, but the

silence of historians is ominous as to his fate.

Immediately on his accession Ratchis concluded a truce with Pope

Zacharias, or rather perhaps with the civil governor of the Ducatus Romae, which was to last for twenty years : and

in fact the relations between Roman and Lombard were peaceable ones during

almost the whole of his short reign. But now that we have lost the guidance of

Paulus Diaconus—an irreparable loss for this

period—it is practically impossible to continue the narrative in the court of

the Lombard kings. History will insist in concerning herself chiefly with the

actions of four men—Zacharias the Greek, Boniface the man of Devonshire, and

the two Frankish Mayors of the Palace. When she is not listening to the

discussions in the Lateran patriarchate, she overpasses the Alps and waits upon

the march of the Frankish armies, or follows the archbishop of Germany in his

holy war against paganism and heresy.

The troubles of Carloman and Pippin did not end with the suppression of

Grifo's rebellion. All round the borders of the realm the clouds hung menacing.

In Aquitaine, Hunold son of Eudo was again raising his head and endeavouring to

assert his independence. Otilo of Bavaria had probably abetted the revolt of

his nephew Grifo, and certainly chafed like Hunold under the Frankish yoke. The

Alamanni in the south, the Saxons in the north, were all arming against the

Franks. It was probably in part at least as the result of these troubles that

the two brothers determined to ‘regularise their position', if we may borrow a

word from the dialect of modern diplomacy, by seating another shadow on the

spectral throne of the Merovingians. Since the death of Theodoric IV in 737

there had been no faineant king sitting in a royal villa or nominally presiding

over the national assembly of the Campus Martius. A certain Childeric, third

king of that name and last of all the Childerics and Chilperics and Theodorics who for

the previous century had been playing at kingship, was drawn forth from the

seclusion probably of some monastery, was set on the archaic chariot to which

the white oxen were yoked, was drawn to the place of meeting, and solemnly

saluted as king. This Childeric's very place in the royal pedigree is a matter

of debate. In the documents which bear his name he meekly alludes to ‘the

famous man Carloman, Mayor of the Palace, who hath installed us in the throne

of this realm'. That he was enthroned in 743 and dethroned in 751 is

practically all that is known of this melancholy figure, ignavissimus Hildericus.

Having thus guarded themselves against the danger of an attack from

behind in the name of Merovingian legitimacy, Carloman and Pippin, who always

wrought with wonderful unanimity for the defence of their joint dominion,

entered upon a campaign against Otilo, duke of Bavaria. Otilo, as has been

said, had probably aided his young nephew Grifo in his attempt at revolution.

He had also formed a league with Hunold, duke of Aquitaine, and with Theobald,

duke of the Alamanni, and openly aimed at getting rid of the overlordship of

the Frankish rulers. Further to embitter the relations between the two states,

he had married Hiltrudis, daughter of Charles Martel,

contrary to the wish of her two brothers. To avenge all these wrongs and to

repress all these attempts at independence ‘the glorious brothers' led their

army into the Danubian plains and encamped on the

left bank of the Lech, the river which flows past Augsburg and was then the

western boundary of the Bavarian duchy. On the opposite bank was the Bavarian

army, with a large number of Alamannic, Saxon, and Sclavic auxiliaries. So the two armies lay for fifteen

days. The river was deemed unfordable, yet Otilo as a matter of extraordinary

precaution had drawn a strong rampart round his camp.

The fortnight passed amid the jeers of the threatened Bavarians.

Possibly too there may have been some heart-searching in the tent of the

Frankish Mayors, for near the close of that period there appeared in the camp

the presbyter Sergius, a messenger from Pope Zacharias, professing to bring the

papal interdict on the war and a command to leave the land of the Bavarians

uninvaded. However, at the end of the fifteen days the Franks, who had found

out a ford by which waggons were wont to pass, crossed the Lech by night, and

with forces divided into two bands fell upon the camp of the Bavarians. The

unexpected attack was completely victorious; the rampart apparently was not

defended; the Bavarian host was cut to pieces, and Otilo himself with a few

followers escaped with difficulty from the field and placed the river Inn

between himself and his triumphant foe. Theobald the Alamannic duke, who must have been also present in the Bavarian camp, saved himself by

flight. But the priest Sergius was taken, and with Gauzebald,

bishop of Ratisbon, was brought into the presence of the two princes. Thereupon

Pippin with calm soul addressed the trembling legate. “Now we know, master

Sergius, that you are not the holy apostle Peter, nor do you truly bear a

commission from him. For you said to us yesterday that the Apostolic Lord, by

St. Peter's authority and his own, forbade our enterprise against the

Bavarians. And we then said to you that neither St. Peter nor the Apostolic

Lord had given you any such commission. Now then you may observe that if St.

Peter had not been aware of the justice of our claim he would not this day have

given us his help in this battle. And be very sure that it is by the

intercession of the blessed Peter the Prince of Apostles and by the just

judgment of God that it is decreed that Bavaria and the Bavarians shall form

part of the Empire of the Franks”.

The invading army remained for fifty-two days in the conquered province.

Otilo seems to have visited the Frankish court as a suppliant, and obtained at

length (perhaps not till after the lapse of a year) the restoration of his

ducal dignity, but with his dependence on the Frankish overlords more

stringently asserted than before, and with a considerably diminished territory,

almost all the land north of the Danube being shorn away from Bavaria and

annexed to Austrasia. Otilo appears to have lived about five years after his

restoration to his duchy, and to have died in 748, leaving an infant son

Tassilo III, of whose fortunes much will have to be said in the following

pages.

For the time, however, we are more concerned with the relation of

Carloman and Pippin to Pope Zacharias; and this indeed is that which has made

it necessary to tell with some detail the story of the Bavarian campaign.

Priest Sergius said that he brought a message from the Pope forbidding the

Frankish princes to make war on Bavaria. Is it certain that he had not in truth

such a commission? He is spoken of by the annalist as the envoy of the Pope,

and though after the battle of the Lech it might be convenient for the Pope and

all belonging to him to acquiesce in the decision of St. Peter as manifested by

the disaster to the Bavarian arms, it is by no means clear that Zacharias, both

as a lover of peace desirous to stay the effusion of Christian blood and also

as a special ally and patron of the lately Christianized Bavarian state, did

not endeavour by spiritual weapons to repel the entrance of the Franks into

that land. Late and doubtful as is the source from which the story of the

mission of Sergius is drawn, it has a certain value as coinciding with other

indications to make us believe that the Papacy still looked coldly on the

Frankish power, that the remembrance of Charles Martel and his highhanded

dealings with Church property was still bitter, and that we are yet in 743 a

long way from that entire accord between Pope and Frankish sovereign which is

the characteristic feature of the second half of the eighth century.

To the influence of one man, a countryman of our own, more than to any

other cause was this momentous change in the relation of the two powers to be

attributed. The amalgam between these most dissimilar metals, the mediator

between these two once discordant rulers, was Boniface of Crediton, the virtual

Metropolitan of North Germany. We have already seen how he consolidated the

ecclesiastical organization of Bavaria, reducing it, as an old Proconsul of the

Republic might have done, into the form of a province abjectly submissive to

Rome. Thuringia and Hesse felt his forming hand. From Carloman, who was

becoming more and more fascinated by his religious fervour, he obtained a grant

of sixteen square miles of sylvan solitude in the modern territory of Hesse Cassel,.

where he founded the renowned monastery of Fulda, which he destined for the

retreat of his old age. But not yet did he dream of retiring from his church-

moulding labours. His influence was felt even in Neustria, and he might almost

have been called at this time the Metropolitan of the whole Frankish realm.

Devoted as Boniface was to the cause of the Papacy, he shrank not from

speaking unpalatable truths even to the Pope when he deemed that the cause of

the good government of the Church required him to do so. In the collection of

his letters there are some which remarkably illustrate this freedom of speech

on the part of the English missionary. In one, Boniface calls upon Zacharias to

put down the ‘auguries, phylacteries and incantations' detestable to all

Christians, which were practised on New Year's Day by the citizens of Rome,

probably in order to obtain a knowledge of the events which should happen in

the newly- opened year. Then again, after Boniface had prayed the Pope to grant

the archiepiscopal pallium to the bishops of Rouen, Rheims and Sens, and Zacharias

had agreed to the proposal and sent the coveted garments, Boniface seems to

have changed his mind and limited his request to one only, on discovering or

suspecting that the Papal curia was asking an exorbitant sum for each of the

pallia. Even the gentle Zacharias was roused to wrath by what seemed to him the

inconstancy and suspiciousness of his correspondent. “We have fallen”, he said,

“into a certain maze and wonderment on the receipt of your letters, so

discordant from those which you addressed to us last August. For in those you

informed us that by the help of God and with the consent and attestation of

Carloman you had held a council, had suspended from their sacred office the

false priests who were not worthy to minister about holy things, and had ordained

three archbishops, giving to each his own metropolis, namely to Grimo the city which is called Rodoma (Rouen), to Abel the city which is called Remi (Rheims) , and to Hartbert the

city which is called Sennis (Sens). All which was at

the same time conveyed to us by the letters of Carloman and Pippin in which you

[all three] suggested to us that we ought to send three pallia to the

before-mentioned prelates, and these we granted to them accordingly for the

sake of the unity and reformation of the Churches of Christ. But now on

receiving this last letter of yours we are, as we have said, greatly surprised

to hear that you in conjunction with the aforesaid princes of Gaul have

suggested one pallium instead of three, and that for Grimo alone. Pray let your Brotherhood inform us why you first asked for three and

then for one, that we may be sure that we understand your meaning and that

there may be no ambiguity in this matter. We find also in this letter of yours

what has greatly disturbed our mind, that you hint such things concerning us as

if we were corrupters of the canons, abrogators of the traditions of the

fathers, and thus—perish the thought—were falling along with our clergy into

the sin of simony, by compelling those to whom we grant the pallium to pay us

money for the same. Now, dearest brother, we exhort your Holiness that your

Brotherhood do not write anything of this kind to us again; since we find it

both annoying and insulting that you should attribute to us an action which we

detest with all our heart. Be it far from us and from our clergy that we should

sell for a price the gift which we have received from the favour of the Holy

Ghost. For as regards those three pallia which as we have said we granted at

your request, no one has sought for any advantage from them. Moreover, the

charters of confirmation, which according to custom are issued from our

chancery, were granted of our mere good will, without our taking anything from

the receivers. Never let such a crime as simony be imputed to us by your

Brotherhood, for we anathematize all who dare to sell for a price the gift of

the Holy Spirit”.

It would be of course a hopeless attempt to endeavour to ascertain the

cause of this strange misunderstanding between two men who seem to have been

both in earnest in their desire for the good government of the Church.

Certainly the impression which we derive from the correspondence is that the

Papal Curia was charging a fee for the bestowal of the pallium, and such an

exorbitant fee that Boniface felt that he must limit his application to one,

when in the interests of the Gaulish Church he would have desired to appoint

three archbishops. It may perhaps be conjectured that the officials of the

Curia were in this matter obeying only their own rapacious instincts and were

acting without the knowledge of their chief, whose character, if we read it

aright, was too gentle and unworldly to make him a strenuous master of such

subordinates. It speaks well for the earnestness and magnanimity of both Pope

and Bishop that the friendly relations between them do not appear to have been

permanently disturbed. Even the letter just quoted concludes with these words :

“You have asked if you were to have the same right of free preaching in the

province of Bavaria which was granted you by our predecessor. Yes, God helping

us, we do not diminish but increase whatever was bestowed upon you by him. And

not only as to Bavaria, but as to the whole province of the Gauls,

so long as the Divine Majesty ordains that you shall live, do you by that

office of preaching which we have laid upon you study in our stead to reform

whatsoever you shall find to be done contrary to the canons and to the

Christian religion, and bring the people into conformity with the law of

righteousness”.

It will be seen how wide was the commission thus given to Boniface,

covering in fact the whole Frankish realm. In conformity therewith we find him

holding synods, not only in Austrasia under the presidency of Carloman, but

also in Neustria under that of his brother; the object of both synods and of

others held at Boniface's instigation being the reform of the morals of the

clergy, the eradication of the last offshoots of idolatry, the tightening of

the reins of Church discipline. Churchmen were forbidden to bear arms or to

accompany the army except in the capacity of chaplains. They were not to keep

hawks or falcons, to hunt, or to roam about in the forests with their dogs.

Severe punishments were ordained for clerical incontinence, especially for the

not uncommon case of the seduction of a nun. A list of survivals of heathenism,

rich in interest for the antiquary and the philologer, was appended to the

proceedings of one of the synods, as well as a short catechism in the German

tongue, containing the catechumen's promise to renounce the devil and all his

works, with Thunar, Woden and Saxnote and all the fiends of their company.

By all this reforming zeal Boniface made himself many enemies. Nothing

but the powerful support of the Pope and the two Frankish Mayors probably saved

him and his Anglo- Saxon companions (the strangers as they were

invidiously called) from being hustled out of the realm by the Gaulish bishops,

who for centuries had scarcely seen a synod assembled. However, with that

support and strong in the goodness of his cause Boniface triumphed. At the

synod of 745 Cologne was fixed upon as the metropolitan see of ‘the Pagan

border-lands and the regions inhabited by the German nations', and over this

great archbishopric Boniface was chosen to preside. Two years later the

metropolitan dignity was transferred to the more central and safer position of

Mainz, Boniface still holding the supreme ecclesiastical dignity. In frequent

correspondence with Zacharias and steadily supported by him, he deposed a

predecessor in the see of Mainz who had in true old German fashion obeyed the

law of the blood-feud by slaying the slayer of his father. He procured the

condemnation of two bishops whom he accused of wild, but doubtless much

exaggerated heresies. We read with regret that Boniface was not content with

deposing these men from their offices in the Church, but insisted on invoking

the help of the secular arm to ensure their life-long imprisonment.

While these events were taking place in the Church, other events in

camps and battlefields were preparing the way for a change in the occupants of

the palace, which took all the world by surprise. The two brothers Carloman and

Pippin fought as before against the Saxons (745) and against the duke of

Aquitaine (746), punishing the latter for his confederacy with Otilo of

Bavaria. But against the restless and faith- breaking Alamanni Carloman fought

alone, and here his impulsive nature, lacking the counterpoise of Pippin's

calmer temperament, urged him into a dreadful deed, and one which darkened the

rest of his days. Something, we are not precisely told what, but apparently

some fresh instance of treachery and instability on the part of the Alamanni,

aroused his resentment, and he entered the Swabian territory with an army. He

summoned a placitum, a meeting of the nation under arms, at Cannstadt on the Neckar. It is suggested that the avowed object of the placitum was a

joint campaign against the Saxons, but this is only a conjecture. Apparently

however the Alamanni came, suspecting nothing, to the place of meeting

appointed by the Frankish ruler. Carloman adroitly stationed his army

(doubtless much the more numerous of the two) so as to surround the Alamannic host, and the latter thus found themselves

helpless when some sort of signal was given for their capture. Some were taken

prisoners, but many thousands, it is said, were slain. Theobald their chief and

the nobles who had joined with him in making a league with Otilo were taken,

and ‘compassionately dealt with according to their several deservings.

Probably this means that there was a kind of judicial enquiry into their cases,

and some may have escaped from the general massacre.

When he came to himself and reflected on what he had done, when he saw,

it may be, how this unknightly deed, more worthy of the chamberlain of a

Byzantine emperor than of a brave duke of the Franks, struck the minds of his

brother warriors, Carloman was filled with remorse. This then was the end of

all those conversations with Boniface, of all those aspirations after a better

and holier life, which had upward drawn his soul. He, the friend of saints, the

reformer of Churches, had done a deed which his rude barbarian forefathers, the

worshippers of Thunor and Woden, would have blushed

to sanction. There was then no possibility of salvation for him in this world

of strife and turmoil. If he would win a heavenly crown he must lay down the

Frankish mayoralty. “In this year Carloman laid open to his brother Pippin a thing

upon which he had long been meditating, namely his desire to relinquish his

secular conversation and to serve God in the habit of a monk. Wherefore

postponing any expedition for that year in order that he might accomplish

Carloman's wishes and arrange for his intended journey to Rome, Pippin gave his

whole attention to this, that his brother should arrive honourably and with

befitting retinue at the goal of his pilgrimage”.

It was near the end of the year 747 when Carloman, with a long train of

noble followers, set out for Italy. He visited on his road the celebrated

monastery of St. Gall, the friend of Columbanus, which he enriched with

valuable gifts. Having therefore probably descended into Italy by the pass of

the Splugen, he proceeded at once to Rome, where he

worshipped at the tomb of St. Peter, and again gave innumerable gifts to the

sacred shrine, among them a silver bow weighing seventy pounds. The fair locks

of the Frankish duke were clipped away; he assumed the tonsure and received the

monastic habit from the hands of Pope Zacharias. From Rome he withdrew to the

solitude of Mount Soracte, and there founded a

monastery in honour of Pope Silvester, who was fabled to have sought this

refuge from the persecution of the Emperor Constantine.

What visitor to Rome has not looked forth towards the north-western

horizon to behold the shape, if once seen never to be forgotten, of Soracte? In winter sometimes, as Horace saw it, ‘white with

deep snow', in summer purple against the sunset sky, but always, (according to

the well-known words of Byron), Soracte

‘from out the plain

Heaves like a long-swept wave about to break

And on the curl hangs pausing.'

But though most travellers are content to behold it from afar, he who

would visit Soraete will find himself well rewarded

for the few hours spent on his pilgrimage. Leaving Rome by the railway to

Florence, the modern equivalent of the Via Flaminia, after a journey of about

forty miles he reaches a station from which a drive of five miles up towards

the hills and out of the valley of the Tiber brings him to Civita Castellana,

the representative of that ancient Etruscan city of Falerii which according to

Livy's story was voluntarily surrendered to Camillus by the grateful parents

whose sons had flogged their treacherous schoolmaster back from the camp to the

city.

Aptly is this place called ‘the castle-city', for it looks indeed like a

natural fortress, standing on a high hill with the land round it intersected by

deep rocky gorges, and these gorges lined with caves, the tombs of the vanished

Etruscans. Soracte soars above in the near

foreground, and thither the traveller repairs, driving for some time through

the ilex-woods which border its base, and then mounting upwards to the little

town of St. Oreste—a corruption probably of Soracte—which

nestles on a shoulder of the mountain. Here the carriage-road ends, but a good

bridle-path leads to the convent of S. Silvestro on the highest point of the

mountain. Ever as the traveller works his way upwards through the grateful

shade of the ilex- woods, he is reminded of Byron's beautiful simile, and feels

that he is indeed walking along the crest of a mighty earth-wave, spell-bound

in the act of breaking. Here on the rocky summit of the mountain, 2,270 feet

above the sea-level, stands the desolate edifice which, though for the most

part less than four centuries old, still contains some of the building reared

by Carloman in honour of Pope Silvester. Unhappily all the local traditions are

concerned with this utterly mythical figure of the papal hermit. The rock on

which Silvester lay down every night to sleep, the altar at which he said mass,

the little garden in which his turnips grew miraculously in one night from seed

to full-fed root, all these are shown, but there is no tradition connecting the

little oratory with the far more interesting and historical figure of the

Carolingian prince. But the landscape at least, which we see from this mountain

solitude, must be the same that he gazed upon : immediately below us Civita

Castellana with its towers and its ravines; eastward, on the other side of the

valley of the Tiber, the grand forms of the Sabine mountains; on the west the Ciminian forest, the Lago Bracciano,

and the faintly discerned rim of the sea; southward the wide plains of the

Campagna and the Hollow Mountain which broods over Alba Longa.

Here, for some years apparently, Carloman abode in the monastery which

he had founded. But even lonely Soracte was too near

to the clamour and the flatteries of the world. The Frankish pilgrims visiting

Rome would doubtless often turn aside and climb the mountain on which dwelt the

son of the warrior Charles, himself so lately their ruler. Longing to be

undisturbed in his monastic seclusion and fearing to be enticed back again into

the world of courtly men, Carloman withdrew to the less accessible sanctuary of

Monte Cassino. Of his life there we have only one description, and it reaches

us from a somewhat questionable source, the Chronicle of Regino, who lived a

hundred years after the death of Carloman; but as the chronicler tells us that

he made up his history partly from the narration of old men his contemporaries,

we may suffer him to paint for us at least a not impossible picture of the

Benedictine life of the Frankish prince. According to this writer, Carloman

fled at night from Soracte with one faithful

follower, taking with him only a few necessary provisions, and reaching the

sacred mountain knocked at the door of the convent and asked for an interview

with its head. As soon as the abbot appeared he fell on the ground before him

and said, “Father abbot! a homicide, a man guilty of all manner of crimes,

seeks your compassion and would fain find here a place of repentance”.

Perceiving that he was a foreigner, the abbot asked him of his nation and his

fatherland, to which he replied, “I am a Frank, and I have quitted my country

on account of my crimes, but I heed not exile if only I may not miss of the

heavenly father-land”. Thereupon the abbot granted his prayer and received him

and his comrade as novices into the convent, but mindful of the precept, “Try

the spirits whether they are of God”, laid upon them a specially severe

discipline, inasmuch as they came from far and belonged to a barbarous race.

All this Carloman bore with patience, and at the end of a year he was allowed

to profess the rule of St. Benedict and to receive the habit of the order.

Though beginning to be renowned among the brethren for his practice of every

monastic virtue, he was not of course exempted from the usual drudgery of the

convent, and once a week it fell to his lot to serve in the kitchen. Here,

notwithstanding his willingness to help, his ignorance caused him to commit

many blunders, and one day the head-cook, who was heated with wine, gave him a

slap in the face, saying, “Is that the way in which you serve the brethren?”.

To which with meek face he only answered, “God pardon thee, my brother”; adding

half-audibly, “and Carloman also”. Twice this thing happened, and each time the

drunken cook's blows were met by the same

gentle answer. But the third time, the faithful henchman, indignant at

seeing his master thus insulted, snatched up the pestle with which they pounded

the bread that had to be mixed with vegetables for the convent dinner, and with

it struck the cook with all his force, saying, “Neither may God spare thee,

caitiff slave, nor may Carloman pardon thee”.

At this act of violence on the part of a stranger received out of

compassion into the convent, the brethren were at once up in arms. The henchman

was placed in custody, and next day was brought up for severe punishment. When

asked why he had dared to lift up his hand against a serving-brother he

replied, “Because I saw that vile slave not only taunt but even strike a man

who is the best and noblest of all that I have ever known in this world”. Such

an answer only increased the wrath of the monks. “Who is this unknown stranger,

whom you place before all other men, not even excepting the father abbot

himself? “. Then he, unable longer to keep the secret which God had determined

to reveal, said, “That man is Carloman, formerly ruler of the Franks, who for

the love of Christ has left the kingdoms of this world and the glory of them,

and who from such magnificence has stooped so low that he is now not only

upbraided but beaten by the vilest of men”. At these words the monks all arose

in terror from their seats, threw themselves at Carloman's feet and implored

his pardon, professing their ignorance of his rank. He, not to be outdone in

humility, cast himself on the ground before them, declared with tears that he

was not Carloman, but a miserable sinner and homicide, and insisted that his

henchman's statement was an idle tale trumped up to save himself from

punishment. But it was all in vain. The truth would make itself manifest. He

was recognized as the Frankish nobleman, and for all the rest of his sojourn in

the convent he was treated with the utmost deference by the brethren.

It was in 747 that Carloman entered the convent. Two years later his

example was followed by the Lombard king, but there is reason to think that in

his case the abdication was not so voluntary an act as it was with Carloman.

King Ratchis, we are told, ‘with vehement indignation' marched against Perugia

and the cities of the Pentapolis. Apparently these cities were not included in

the strictly local truce which he had concluded for twenty years with the

rulers of the Ducatus Romae.

But Pope Zacharias, mindful of his previous successes in dealing with these

impetuous Lombards, went as speedily as possible northwards with some of the

chief men of his clergy. He found Ratchis besieging Perugia, but exhorted him

so earnestly to abandon the siege that Ratchis retired from the untaken city.

Nay, more, says the papal biographer (for it is his narrative that we are here

following), Zacharias awakened in the king's mind such earnest care about the

state of his soul, that after some days he laid aside his royal dignity, came

with his wife and daughters to kneel at the tombs of the Apostles, received the

tonsure from the Pope, and retired to the monastery of Cassino, where he ended

his days.

This is the papal story of king Ratchis' abdication, but a study of the

laws of his successor seems to confirm the statement (made it is true on no

very good authority) that it was really the result of a revolution. This

authority, the Chronicon Benedictanum , tells us that

the queen of Ratchis, Tassia, was a Roman lady, and that under her influence

Ratchis had broken down the old Lombard customs of morgincap and met-fiu (the money payments made on the betrothal

and marriage of a Lombard damsel), and had given grants of land to Romans

according to Roman law. All this may have made him unpopular with the stern

old-world patriots among his Lombard subjects. But it is conjectured with some

improbability that it was their king's retreat from the walls of untaken

Perugia and his too easy compliance with the entreaties of Zacharias which at

last snapped the straining bond of his subjects' loyalty.

Whatever the cause may have been, the fact is certain. The Lombard

throne was declared to be empty, and Aistulf, brother of the displaced king,

was invited to ascend it (July, 7491). There may not have been bloodshed, but

there was almost certainly resistance on the part of the dethroned monarch, for

the first section of the new king's laws, published soon after his accession,

provides that, ‘As for those grants which were made by king Ratchis and his

wife Tassia, all of these which bear date after the accession of Aistulf shall

be of no validity unless confirmed by Aistulf himself.'

Thus these two men, lately powerful sovereigns, Carloman and Ratchis,

are meeting in church and refectory in the high-built sanctuary of St. Benedict

on Monte Cassino. We shall hereafter have to note the emergence of both from

that seclusion, on two different occasions and with widely different motives.

|

|

|

|