|

READING HALLTHE DOORS OF WISDOM |

|

|

|

|||

ITALY AND HER INVADERS.BOOK VIII.

|

|

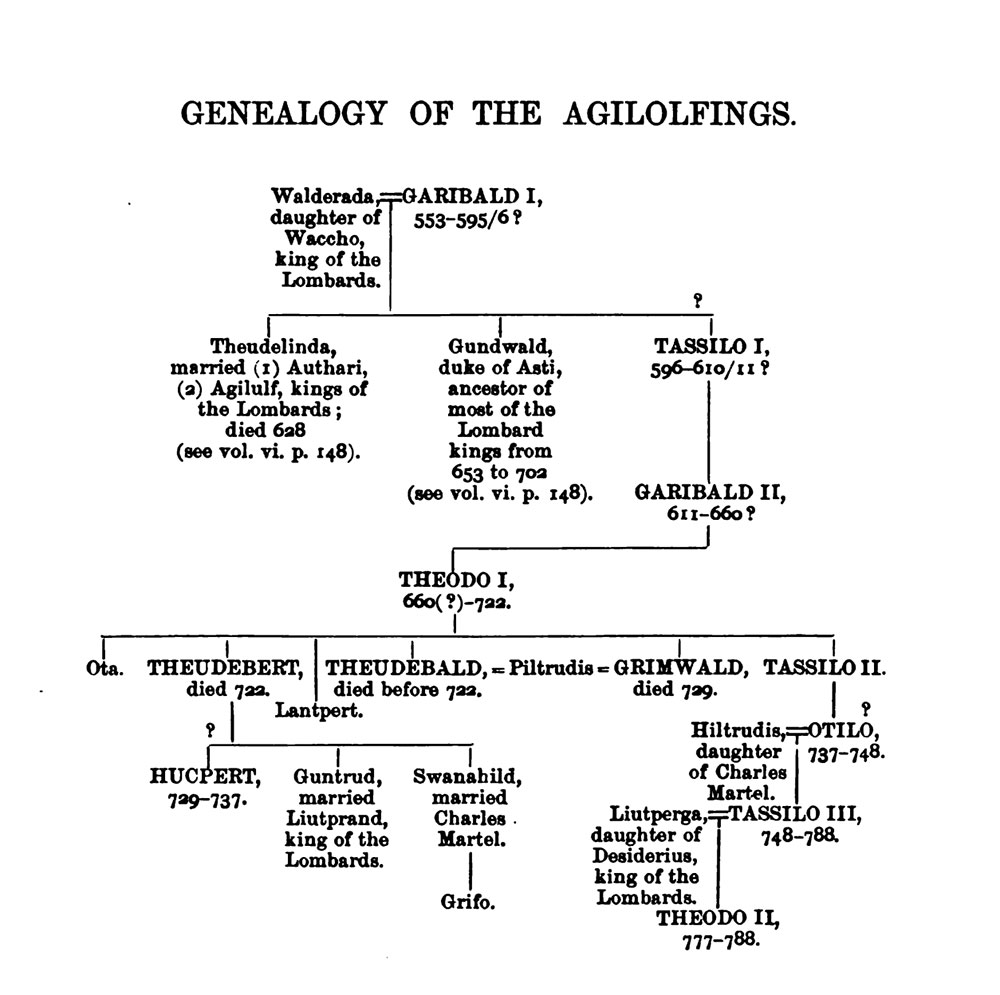

The first of these Agilolfing rulers of whom

history makes mention is Garibald, husband of the Lombard princess Walderada, who was the divorced wife of the Frankish king

Chlotochar. His daughter Theudelinda was the celebrated and saintly queen of

the Lombards. The reader may remember the romantic stories of her wooing by the

disguised Authari and of the cup of wine which she handed to the favoured

Agilulf. From some cause which is unknown to us Garibald incurred the

displeasure of his Frankish lords and probably had to submit to a Frankish

invasion . There is no proof however that he lost his ducal crown, and about

the year 596 he seems to have been succeeded by a son named Tassilo I

(596-611). It is indeed nowhere distinctly stated that this was the relationship

between the two princes, but the fact that Tassilo's son and successor was

named Garibald II renders it probable.

Of the reigns of these early dukes of Bavaria we know very little, nor

can we with any certainty fix the date of the second Garibald's possession of

power. It seems clear, however, that through the greater part of the seventh

century the bond of allegiance to the Frankish monarchy was growing looser and

looser; faineant Merovingian kings and warring Mayors of the Palace having

little power to enforce its obligations. The duke seems to have surrounded

himself with seneschal and marischal and all the

other satellites of a sovereign prince, and his capital, Ratisbon on the

Danube, doubtless outshone Paris and Metz in the eyes of his Bavarian subjects.

With the accession to the ducal throne of Theodo I (660-722) we gain a

clearer vision of Bavarian affairs from the lives of the saints, Rupert,

Emmeran, and Corbinian, who came from Gaul and from Ireland to effect the

conversion of the people. It is indeed surprising to us who have witnessed the

earnest zeal of the Bavarian Theudelinda, not merely for Christianity but for

orthodoxy among her Italian subjects, to find that, two generations later, her

own Bavarian countrymen still needed conversion. But apparently the

Christianity of Garibald's court was not much more than a court fashion (the

result very possibly of his own Frankish origin), and had not deeply leavened

the mass of his subjects. Probably we are in the habit of underestimating the

stubbornness of the resistance of Teutonic heathenism to the new faith. When a

tribe like the Franks or the Burgundians settled in the midst of a people

already imbued with Christian ideas through their subjection to the Empire, it

was comparatively easy to persuade them to renounce idolatry or to change the

Arian form of Christianity for the Athanasian. But when the messengers of the

Church had to deal with nations all Teutonic and all heathen, like the

Frisians, the Saxons, or the Bavarians, the process of conversion (as we know

from the history of our own forefathers) was much slower and more laborious.

Thus it came to pass that in the middle of the seventh century the mass of the

Bavarian folk were apparently still heathen, worshipping the mysterious goddess

Nerthus, and venerating a statue of Irmin in the sacred wood, feasting on

horse-flesh in the half-ruined temple which had perhaps once been dedicated to

Jupiter or Isis, and offering, with drunken orgies, sacrifices of rams and

goats beside the bier of their dead comrades, to commemorate their entrance

into Walhalla.

Into this rude, more than half-Pagan world came towards the end of the

seventh century bishop Rupert or Hroudbert of Worms.

His ancestry and birthplace are doubtful. Some have described him as sprung

from Ireland, while others make him a Frank, of kin to the royal house of the

Merovingians. He came into Bavaria, we are told, at the invitation of the duke,

but probably also with the full consent if not at the actual suggestion of the

great Frankish Mayor, Pippin of Heristal, who at this time not only by warlike

expeditions but also by wise and politic counsels was tightening once more the

loosened bonds which bound the Bavarians as well as the other nations east of

the Rhine to the Frankish kingdom.

At the outset of his operations Rupert baptized duke Theodo and then

proceeded with the conversion of the heathen remnant of his people to

Christianity, reconsecrating old temples which still bore the names we are told

of Juno and Cybele, and dedicating them to the Virgin, and ever on the quest

for some one place where he might found a monastery which he might make the

centre of his missionary work. Not desirous apparently of too near

neighbourhood to the ducal court at Ratisbon, he decided at last upon the

little Waller See about seven miles from Salzburg, where he founded the

monastery of the Church-by-the-Lake (See-Kirche). But

not long had he dwelt here when the desolate ruins of the once stately Roman

city of Juvavia attracted his notice. Still desolate,

two centuries after that destruction which St. Severinus had foretold of them

and the other cities of Noricum, they attracted and fascinated him by their

mouldering greatness. He obtained from duke Theodo a grant of the old city and

of the fort above, with twenty farms and twenty salt-pans at Reichenhall,

eighty ‘Romans ' with their slaves, all the unoccupied lands in the district of

Salzburg, and other rights and royalties. High up on that noble hill which

still bears the name of the Monk's Mountain Rupert reared his church, which he

dedicated to St. Peter, and founded there his monastery, which he put under the

guidance of twelve young Franks, his disciples and fellow-countrymen. Such was

the beginning of the great and rich bishopric of Salzburg.

It was probably about the time of Rupert’s first missionary operations

in Bavaria that duke Theodo, now past the middle of life, divided his duchy

between himself and three of his sons. Of these sons the only one of whom we

hear anything important is Grimwald, whose capital was Freising, about twenty

miles north-east of Munich, and who probably ruled over that part of Bavaria

which lies between the Danube and the Alps.

Soon after this division of the duchy and about the time of the death of

Pippin of Heristal, we may conjecturally place the appearance of the second

great Frankish missionary in Bavaria, Emmeran of Poitiers: a meteoric

appearance which heralded storm and was strangely quenched in darkness. Emmeran

came, we are told, into Bavaria, intending only to traverse the country on his

way to the barbarous Avars, of whom he desired to make proselytes. He came to

the strongly fortified city of Ratisbon and stood before duke Theodo, but an

interpreter was needed to mediate between the speech of Aquitaine and the

speech of Bavaria. He explained to the duke the object of his mission, and

Theodo replied, “That land to which thou wouldest fain go, on the banks of the Ens, is lying all waste and desolate, through the

incursions of the Avars. Stay rather here, and I will make thee bishop in this

province, or give thee the oversight of some abbey”. And Emmeran, learning that

the conversion of the Bavarians was yet but half accomplished and that they

still blended their heathen sacrifices with the Supper of the Lord, was

persuaded to stay in that fruitful land, whose inhabitants pleased him well,

and he preached there during three years.

Now Emmeran was a man of noble stature and comely face, generous both of

speech and of money, and extraordinarily affable to women as well as to men :

evidently a courtly bishop rather than an austere recluse. Unfortunately at the

end of the three years the princess Ota, duke Theodo’s daughter who had fallen into sin, accused the Frankish missionary as her

seducer, and either through consciousness of guilt, or through unworldly

carelessness as to his good name, he took no steps to clear himself of the

charge. He left Bavaria indeed, but it was not to prosecute his journey to

Avar-land, but to cross the Alps to Rome. A son of duke Theodo named Lantpert

pursued after him, and having overtaken him ere he had reached the mountains,

inflicted upon him the punishment of an incontinent slave, mutilation of the

tongue, the hands and the feet. He died of his wounds, and the Church (which

was persuaded of his innocence of the charge against him) reverenced him as a

martyr.

In the year 716, soon probably after the death of Emmeran, Theodo with a

long train of dependants visited Rome to pray at the tomb of St. Peter. As has

been already suggested, the visit was probably connected in some way with the

terrible event which had preceded it, and it is possible that the

reconciliation of the ducal family to the Pope may have been accomplished at

the price of some concessions which made the Bavarian Church more dependent on

the see of Rome.

The third great Frankish missionary, Corbinian, was a man of hot and

choleric temper, and he, like Emmeran, had his quarrels with the ducal house of

Bavaria, though they did not for him end in such dire disaster. Born at a place

called Castrus near Melun about the year 68o, he was

the son of a mother already widowed who probably fostered her child's

domineering and impetuous disposition. He seems also to have been a man of

wealth and some social importance, and accordingly, when his genius took the

direction of miracle-working and monastic austerity, the fame of his young

saintliness easily penetrated the court and reached the ears of the aged Pippin

of Heristal, who probably encouraged him to turn his energies to the building

up of a Frankish-Christian Church in barbarous Bavaria. After fourteen years of

retirement in his cell, he journeyed to Rome, ‘in order to ask of the Pope

permission to spend his life in solitude',' says his admiring biographer Aribo. But the Pope, we are told, perceiving his fitness for

active work in the Church, and determined that he should not hide his light

under a bushel, utterly refused to grant him the required permission to lead an

anchorite's life, pushed him rapidly through all the lower grades of the

hierarchy and consecrated him bishop, without however assigning him any

definite see, so that he must have been looked upon as a bishop in partibus. After this consecration we are surprised to

hear of his spending the next seven years in the cell of St. Germanus in his

native place. This and some other suspicious circumstances of the story incline

some scholars to believe that the whole tale of this earlier episcopate is a

figment of the biographer.

After this interval of seven years Corbinian appears in Bavaria, intent,

we are told, on undertaking a second journey to Rome. He chose, says Aribo, ‘the more secret way through Alamannia,

Germany, and Noricum' [Bavaria], instead of taking ‘the public road' from the

regions of Gaul. Arrived in Bavaria he found there the devout Theodo, who had

lately accomplished the partition of his duchy with his sons. The eldest

survivor of these sons, Grimwald, eagerly welcomed the saint, and offered if he

would remain to make him co-heir with his own children, doubtless only of his

personal property. Corbinian however rejected this offer, and insisted on

continuing his journey to Rome. Finding it impossible to change his purpose,

Grimwald dismissed him with large presents and gave him an honourable escort,

but at the same time gave secret orders to the dwellers in the Vintschgau that on his return he should be arrested at the

moment of his crossing the Bavarian frontier. We see at once that there is

something more here than the biographer chooses to communicate. The Bavarian

prince looks on the expected return of the great ecclesiastic from beyond the

Alps with the same sort of feelings which induced Plantagenet princes to decree

the penalties of praemunire against any one who should import into England

bulls from Rome.

Corbinian accomplished his journey into Italy. He was ill-treated by Husingus, duke of Trent, who stole from him a beautiful

stallion which he refused to sell, but was kindly received by king Liutprand at

Pavia. He remained here seven days, chiefly occupied in preaching to the king,

who listened with gladness to his copious eloquence. When he was leaving the

capital he again had one of his horses stolen, by a Lombard courtier, whose

dishonesty he detected and whose punishment he foretold. At last after divers

adventures he reached Rome, and here, in spite of his entreaties and his tears,

the Pope (probably Gregory II) ordered him once more to abjure a life of

solitude and to undertake active ecclesiastical work. On his return he again

visited Pavia, and on his arrival at that place the first object that met his

gaze was the body of the Lombard nobleman who had stolen his horse laid upon a

bier and carried forth to burial. The horse was restored, and the widow of the

culprit, grovelling at the saint's feet, besought him to accept 200 solidi

(£120), which her husband on his death-bed had ordered her to pay as the

penalty of his crime.

With a long train of horses and servants Corbinian now took his journey

up the valley of the Adige in order to return into Bavaria by the pass of the

Brenner. Scarcely, however, had he entered the Bavarian territory when by

Grimwald's orders he was arrested at Castrum Magense.

And now we hear something more of the cause of Grimwald's fear of the

holy man. The Bavarian duke had married a young Frankish lady of noble birth

named Piltrudis, who was the widow of his brother Theudebald. Against this kind of union, as we know, Rome

uttered strong though not always irrevocable protests, and it was possibly from

fear of Corbinian's bringing across the Alps a bull of excommunication of the

guilty pair that Grimwald had given orders for his arrest on entering the

duchy. However, after a struggle, the details of which are very obscurely

given, Corbinian obtained a temporary victory. Grimwald obeyed the order of the

saint, backed as he probably was by the Frankish Major-Domus, and within the

specified time of forty days put away Piltrudis.

It is needless to say that the divorced wife, who is looked upon by the

ecclesiastical historians as another Herodias, was full of resentment against

the author of her disgrace and vowed to compass his downfall. If we read the

story rightly, the saint's own choleric temper—even his biographer confesses

that he was easily roused to anger by vice, though ready to forgive—aided her

designs.

One day when Corbinian was reclining at the table with the duke he made

the sign of the cross over the food set before him, at the same time giving

praise to God. But the prince took a piece of bread and thoughtlessly threw it

to a favourite hound. Thereat the man of God was so enraged that he kicked over

the three-legged table on which the meal was spread and scattered all the

silver dishes on the floor. Then starting up from his seat he said, “The man is

unworthy of so great a blessing who is not ashamed to cast it to dogs”. Then he

stalked out of the house, declaring that he would never again eat or drink with

the prince nor visit his court.

Some time after this there was another and more violent outbreak of the

saint's ill-temper. Riding forth one day from the royal palace he met a woman

who, as he was told, had effected the cure of one of the young princes by

art-magic. At this he trembled with fury, and leaping from his horse he

assaulted the woman with his fists, took from her the rich rewards for the cure

which she was carrying away from the palace, and ordered them to be distributed

among the poor. The beaten and plundered sorceress, who was perhaps only a skillful female physician, presented herself in Grimwald's

hall of audience with face still bleeding from the saintly fists, and clamoured

for redress. Piltrudis, who seems to have returned to

her old position, seconded her prayer, and Corbinian was banished from the

ducal presence. He had already received from his patron a grant of the place

upon which he had set his heart, Camina, about five miles north of Meran in the

Tyrol, with its arable land, its vineyards, its meadows, and a large tract of

the Rhaetian Alps behind it, and thither he retired to watch for the fulfillment of the prophecies which he had uttered against

the new Ahab and Jezebel.

The longed-for vindication came partly from foreign arms, partly from

domestic treachery. It is possible that Grimwald had to meet a combined

invasion both from the north and from the south, for, as Paulus Diaconus informs us, Liutprand, king of the Lombards, ‘in

the beginning of his reign took many places from the Bavarians'. This may be

the record of some warlike operations undertaken in the troublous years which followed the death of old duke Theodo (722), and may point to some

attempt on the part of the Lombard king, who had married the niece of Grimwald,

to vindicate the claims of her brother Hucpert, whom

Grimwald seems to have excluded from the inheritance of his father's share in

the duchy. This however is only conjecture, and as Liutprand came to the throne

in 712 it is not perhaps a very probable one. But it is certain that in 725 the

great Frankish Mayor, Charles Martel, entered the Bavarian duchy, possibly to

support the claims of Hucpert, but doubtless also in

order to rivet anew the chain of allegiance which bound Bavaria to the Frankish

monarchy. In 728 he again invaded the country, and this invasion was speedily

followed by the death of Grimwald (729). He was slain by conspirators says the

biographer of Corbinian, who adds, with pious satisfaction, that all his sons,

‘deprived of the royal dignity, with much tribulation gave up the breath of

life', but it is probable that all these events were connected with the blow to

Grimwald's semi-regal state which had been dealt by Charles the Hammer.

After one of his invasions of Bavaria, perhaps the first of the two,

Charles Martel carried back with him into Frankland two Bavarian princesses, Piltrudis, the ‘Herodias' of Corbinian's denunciations, and

her niece Swanahild, sister of Hucpert. The latter

lady became, after the fashion adopted by these lax moralists of the

Carolingian line, first the mistress and afterwards the wife of her captor, and

she with the son Grifo whom she bare to Charles caused in after years no small

trouble to the Frankish state.

The result of this overthrow of Grimwald was the establishment on the

Bavarian throne of his nephew Hucpert, son of

Theudebert, brother-in-law of Liutprand the Lombard and Charles the Frank, who

ruled for eight uneventful years, at peace apparently with his nominal overlord

the Merovingian king and his mighty deputy. On his death in 737 the vacant

dignity was given to his cousin Otilo who ruled for eleven years (737-748), and

to whom Charles Martel gave his daughter Hiltrudis in

marriage.

The reign of Otilo (737-748) was chiefly memorable for the

reorganisation of the Bavarian Church by the labours of an Anglo-Saxon

missionary, the great archbishop Boniface. The offshoot of Roman Christianity

planted in Britain by direction of Gregory the Great had now at last, after

much battling with the opposition both of heathenism and of Celtic

Christianity, taken deep root and was overspreading the land. It is not too

much to say that in the eighth century the most learned and the most exemplary

ecclesiastics in the whole of Western Christendom were to be found among those

Anglian and Saxon islanders whose not remote ancestors had been the fiercest of

Pagan idolaters. But precisely because they were such recent converts and

because the question between the Celtic Christianity of Iona and the Roman

Christianity of Canterbury had long hung doubtful in the scale, were these

learned, well-trained ecclesiastics among the most enthusiastic champions of

the supremacy of the Roman see. To us who know what changes the years have

brought, it seems a strange inversion of their parts to find the Celtic

populations of Ireland and the Hebrides long resisting, and at last only with

sullenness accepting, the Papal mandates, while a sturdy Englishman such as

Boniface almost anticipates Loyola in his devotion to the Pope, or Xavier in

his eagerness to convert new nations to the Papal obedience.

Born at Crediton in Devonshire about 775, and the son of noble parents,

the young Wynfrith (for that was his baptismal name),

after spending some years in a Hampshire monastery and receiving priest's

orders, determined to set forth as a missionary to the lands beyond the Rhine,

in order to complete the work which had been began by his fellowcountryman Willibrord. With his work in Frisia and Thuringia we have here no concern. We

hasten on to a visit, apparently a second visit, which he paid to Rome about the

year 722 when he had already reached middle life. It was on this occasion

probably that he assumed the name of Bonifatius; and at the same time he took

an oath of unqualified obedience to the see of Rome, the same which was taken

by the little suburbicarian bishops of the Campagna, save that they bound

themselves to loyal obedience to ‘the most pious Prince and the Republic' ,an

obligation which Boniface in his contemplated wanderings over central Europe,

free from all connection with Imperial Constantinople or with the civic

community of Rome, refused to take upon himself. His eager obedience was

rewarded by a circular letter from the Pope calling on all Christian men to aid

the missionary efforts of ‘our most reverend brother Boniface', now consecrated

bishop in partibus infidelium,

and setting forth to convert those nations in Germany and on the eastern bank

of the Rhine who were still worshipping idols and living in the shadow of

death. At the same time a letter of commendation addressed to the Pope's

‘glorious son duke Charles' obtained from Charles Martel a letter under his

hand and seal addressed to ‘all bishops, dukes, counts, vicars, lesser

officers, agents and friends' warning them that bishop Boniface was now under

the mundeburdium of the great Mayor, and that

if any had cause of complaint against him it must be argued before Charles in

person.

As has been already observed, the protection thus granted by the mighty

Austrasian to the Anglo-Saxon missionary powerfully aided his efforts for the

Christianization of Germany. The terror of the Frankish arms, as well as a

certain vague desire to watch the issue of the conflict between Christ and

Odin, may have kept the Hessian idolaters tranquil while the elderly Boniface

struck his strong and smashing blows at the holy oak of Geismar. At any rate,

truehearted and courageous preachers of the faith as were Boniface and the

multitude of his fellowcountrymen and

fellow-countrywomen who crossed the seas to aid his great campaign, it is clear

that the fortunes of that spiritual campaign did in some measure ebb and flow

with the varying fortunes of the Frankish arms east of the Rhine.

Some time after the death of Gregory II Boniface again visited Rome

(about 737) and received, apparently at this time, from Gregory III the dignity

of Archbishop and a commission to set in order the affairs of the Church in

Bavaria. In fulfilling this commission he must have had the entire support of

the then reigning duke Otilo; but it is not so certain that he was still acting

in entire harmony with the Frankish Mayor. We have seen that after his death

the memory of Charles Martel was subjected to a process the very opposite of

canonization, and there are some indications that at this time the obedient

Otilo of Bavaria was looked upon at Borne with more favour than the too

independent Mayor of the Palace who refused to help the Pope against his

brother-in-law the king of the Lombards. However this may be, it is clear that

Boniface accomplished in Bavaria something not far short of a spiritual

revolution. He had been instructed by the Pope to root out the erroneous

teaching of false and heretical priests and of intruding Britons. The latter

clause must be intended for the yet unreconciled missionaries of the Celtic

Church. Is it possible that the Frankish emissaries were also looked upon with

somewhat of suspicion, that the work of the Emmerans and Corbinians was only half approved at Rome, even

as the life of Boniface certainly shines out in favourable contrast with the

ill-regulated lives of those strange preachers of the Gospel?

“Therefore”, says the Pope to the Archbishop, “since you have informed

us that you have gone to the Bavarian nation and have found them living outside

the order of the Church, since they had no bishops in the Church save one named Vivilo [bishop of Passau], whom we ordained long ago,

and since with the assent of Otilo, duke of the same Bavaria, and of the nobles

of the province you have ordained three more bishops and have divided that

province into four parrochiae, of which each

bishop is to keep one, you have done well and wisely, my brother, since you

have fulfilled the apostolic precept in our stead. Therefore cease not, most

reverend brother, to teach them the holy Catholic and Apostolic tradition of

the Roman see, that those rough men may be enlightened and may hold the way of

salvation whereby they may arrive at eternal rewards”.

Here then at the end of the fourth decade of the eighth century we leave

the great Anglo- Saxon archbishop uprooting the last remnants of heathenism

which his predecessors had allowed to grow up alongside of the rites of

Christianity ; forbidding the eating of horseflesh, the sacrifices for the

dead, and the more ghastly sacrifices of the living for which even so-called

Christian men had dared to sell their slaves; everywhere working for

civilization and Christianity, but doubtless at the same time working to bring

all things into more absolute dependence on the see of Rome. In him we see the

founder, perhaps the unconscious founder, of that militant and lavishly endowed

Churchmanship which found its expression later on in the great

Elector-Bishoprics of the Rhine. We shall meet again in future chapters both

with Boniface and with the Dukes of Bavaria.

|

|

|

|