|

HAILE SELASSIE1892 – 1975EMPEROR OF ETHIOPIA1930-1974WITH A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE HISTORY OF ETHIOPIA, AND A DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY AND ITS PEOPLESBOOK CONTENTSIntroductionI. Emperor at BayII. The Emperor’s SecretIII. Ethiopia, the Unconquerable LandIV. The Historica BackgroundV. Solomon and ShebaVI. Christianity and the Coptic ChurchVII. The Writings of CosmasVIII. The Legend of Prester JohnIX. The Portuguese AdventurersX. King TheodoreXI. The Emperor MenelekXII. The Vision of Ras MakonnenXIII. The Youth of Haile SelassieXIV. The Downfall of Lidj YassuXV. ZawdituXVI. The Feud with ItalyXVII. Ethiopia Joins the LeagueXVIII. The Truth About SlaveryXIX. ConcessionsXX. The Great CoronationXXI. The Daily Life of the EmperorXXII. An Emperor WorshipsXXIII. The Revolt of Ras HailuXXIV. WarXXV. The Treachery of Haile Selassie GugsaXXVI. Where are they Tending?------------------------------A History of Abyssinia [Ethiopia] By A.H.M. Jones and Elizabeth MonroeTHE NILOTIC SUDAN AND ETHIOPIA , C. 660 BC-.AD 600ETHIOPIA, ERITREA AND SOMALILANDSlavery and the Slave Trade in Ethiopia and EritreaWITH THE MISSION TO MENELIK, 1897THE BOOK OF THE SAINTS OF THE ETHIOPIAN CHURCHA HISTORY OF ETHIOPIA NUBIA & ABYSSINIA (ACCORDING TO THE HIEROGLYPHIC INSCRIPTIONS OF EGYPT AND NUBIA, AND THE ETHIOPIAN CHRONICLES)ETHIOPIA. The study of a polity , 1540 - 1935ETHIOPIA

|

|

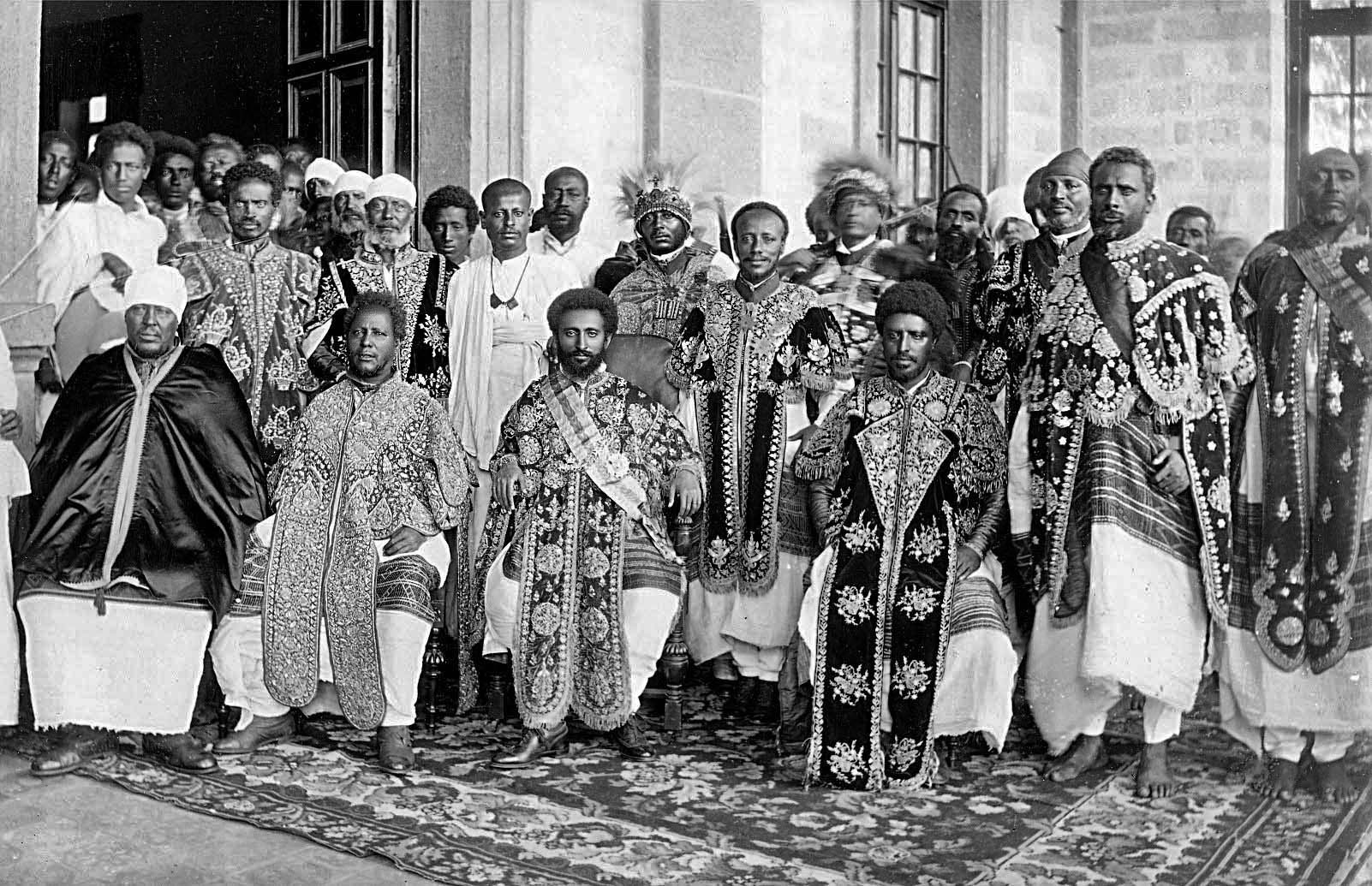

Negusa Nagast Haile Selassie with other Ethiopian nobles and retainers. |

Menelik II (name Abba Dagnew: 17

August 1844 – 12 December 1913), baptised as Sahle Maryam was King of Shewa from 1866 to 1889

and Emperor of Ethiopia from 1889 to his death in 1913. At the height of

his internal power and external prestige, the process of territorial expansion

and creation of the modern empire-state was completed by 1898.[

The Ethiopian Empire was transformed under Emperor

Menelik: the major signposts of modernisation were

put in place, with the assistance of key ministerial advisors. Externally,

Menelik led Ethiopian troops against Italian invaders in

the First Italo-Ethiopian War; following a decisive victory at

the Battle of Adwa, recognition of Ethiopia's independence by external

powers was expressed in terms of diplomatic representation at his court and

delineation of Ethiopia's boundaies with the adjacent

kingdoms. Menelik expanded his realm to the south and east,

into Oromo, Kaffa, Sidama, Wolayta and other kingdoms or peoples.

Later in his reign, Menelik established the first

Cabinet of Ministers to help in the administration of the Empire, appointing

trusted and widely respected nobles and retainers to the first Ministries. These

ministers would remain in place long after his death, serving in their posts

through the brief reign of Lij Iyasu (whom

they helped depose) and into the reign of Empress Zewditu.

Early life

Menelik was the son of the

Shewan Amhara king, Negus Haile Melekot,

and probably of the palace servant girl Ejigayehu Lemma Adyamo. He

was born in Angolalla and baptized to the

name Sahle Maryam. His father, at the age of 18 before inheriting the

throne, impregnated Ejigayehu, then left her; he did not recognize that

Sahle Maryam was born. The boy enjoyed a respected position in the royal

household and he received a traditional church education.

In 1855 the Emperor of Ethiopia, Tewodros II,

invaded the then semi-independent kingdom of Shewa. Early in the subsequent

campaigns, Haile Malakot died, and Sahle Miriam was captured and taken to the

emperor’s mountain stronghold, Amba Magdela.

Still, Tewodros treated the young prince well, even offering him marriage to

his daughter Altash Tewodros, which Menelik accepted.

Upon Menelik's imprisonment, his uncle, Haile

Mikael, was appointed as Shum of Shewa by Emperor Tewodros II with the

title of Meridazmach. However, Meridazmach Haile Mikael rebelled against Tewodros,

resulting in his being replaced by the non-royal Ato Bezabeh as Shum. Ato Bezabeh in turn rebelled against the Emperor and proclaimed

himself Negus of Shewa. Although the Shewan royals imprisoned at Magdela had been largely complacent as long as a member of

their family ruled over Shewa, this usurpation by a commoner was not acceptable

to them. They plotted Menelik's escape from Magdela;

with the help of Mohammed Ali and Queen Worqitu of Wollo, he escaped from Magdala on the night of 1

July 1865, abandoning his wife, and returned to Shewa. Enraged, Emperor Tewodros

slaughtered 29 Oromo hostages then had 12 Amhara notables

beaten to death with bamboo rods.

King of Shewa

Bezabeh's attempt to raise an army against Menelik failed; thousands of Shewans rallied to the flag of the son of Negus Haile Melekot and even Bezabeh's own

soldiers deserted him for the returning prince. Abeto Menelik entered Ankober and proclaimed

himself Negus.

While Negus Menelik reclaimed his ancestral Shewan

crown, he also laid claim to the Imperial throne, as a direct descendant male

line of Emperor Lebna Dengel. However, he made no overt attempt to assert

this claim at this time; Marcus interprets his lack of decisive action not only

to Menelik's lack of confidence and experience but that "he was

emotionally incapable of helping to destroy the man who had treated him as a

son." Not wishing to take part in the 1868 Expedition to

Abyssinia, he allowed his rival Kassai to benefit with gifts of

modern weapons and supplies from the British. When Tewodros committed

suicide, Menelik arranged for an official celebration of his death even though

he was personally saddened by the loss. When a British diplomat asked him why

he did this, he replied "to satisfy the passions of the people ... as for

me, I should have gone into a forest to weep over ... [his] untimely death ...

I have now lost the one who educated me, and toward whom I had always cherished

filial and sincere affection."

Afterwards other challenges – a revolt amongst

the Wollo to the north, the intrigues of

his second wife Befana to replace him with her choice of ruler,

military failures against the Arsi Oromo to the southeast – kept

Menelik from directly confronting Kassai until after his rival had brought

an Abuna from Egypt who crowned him Emperor Yohannes IV.

Menelik was cunning and strategic in building his

power base. He organised extravagant three-day feasts

for locals to win their favour, liberally built

friendships with Muslims (such as Muhammad Ali of Wollo)

and struck alliances with the French and Italians who could provide firearms

and political leverage against the Emperor. In 1876, an Italian expedition set

out to Ethiopia led by Marchese Orazio Antinori who described King

Menelik as "very friendly, and a fanatic for weapons, about whose

mechanism he appears to be most intelligent". Another Italian wrote for

Menelik, "he had the curiosity of a boy; the least thing made an

impression upon him ... He showed ... great intelligence and great mechanical

ability". Menelik spoke with great economy and rapidity. He never became

upset, Chiarini adds, "listening calmly, judiciously [and] with good sense

... He is fatalistic and a good soldier, he loves weapons above all else".

The visitors also confirmed that he was popular with his subjects, and made

himself available to them. Menelik had political and military acumen and

made key engagements that would later prove essential as he expanded his

Empire.

On 10 March 1889, Emperor Yohannes IV was killed in a

war with the Mahdist State during the Battle of Gallabat (Metemma). With

his dying breath, Yohannes declared his natural son, Dejazemach Mengesha

Yohannes, to be his heir. On 25 March, upon hearing of the death of Yohannes,

Negus Menelik immediately proclaimed himself as Emperor.

Menelik argued that while the family of Yohannes IV

claimed descent from King Solomon and the Queen of

Sheba through females of the dynasty, his own claim was based on

uninterrupted direct male lineage which made the claims of the House of Shewa

equal to those of the elder Gondar line of the dynasty. Menelik, and

later his daughter Zewditu, would be the last Ethiopian monarchs who could

claim uninterrupted direct male descent from King Solomon and the Queen of

Sheba (both Lij Iyasu and

Emperor Haile Selassie were in the female line, Iyasu through his

mother Shewarega Menelik, and Haile Selassie through

his paternal grandmother, Tenagnework Sahle

Selassie).

In the end, Menelik was able to obtain the allegiance

of a large majority of the Ethiopian nobility. On 3 November 1889, Menelik was

consecrated and crowned as Emperor before a glittering crowd of dignitaries and

clergy by Abuna Mattewos, Bishop of Shewa, at the

Church of Mary on Mount Entoto. The newly

consecrated and crowned Emperor Menelik II quickly toured the north in force.

He received the submission of the local officials in Lasta, Yejju, Gojjam, Wollo, and Begemder.

Conquest of neighboring states and defeat of the

Italians

Menelik II is argued to be the founder of modern

Ethiopia. Before Menelik's colonial conquests, Ethiopia and Adal

Sultanate had been devastated by numerous wars, the most recent of which

was fought in the 16th century. In the intervening period, military

tactics had not changed much.

In the 16th century, the Portuguese Bermudes

documented depopulation and widespread atrocities against civilians and

combatants (including torture, mass killings and large scale slavery) during

several successive Gadaa conquests led by Aba Gedas of territories

located north of Genale river (Bali, Amhara, Gafat, Damot, Adal. Warfare

in the region essentially involved acquiring cattle and slaves, winning

additional territories, gaining control over trade routes and carrying out

ritual requirements or securing trophies to prove masculinity. Menelik’s

clemency to Ras Mengesha Yohannes, whom he made hereditary Prince of his

native Tigray, was ill repaid by a long series of revolts. In 1898,

Menelik crushed a rebellion by Ras Mengesha Yohannes (who died in 1906). After

this, Menelik directed his efforts to the consolidation of his authority, and

to a degree, to the opening up of his country to outside influences.

The League of Nations in 1920 reported that

after the invasion of Menelik's forces into non Abyssinian lands

of Somalis, Harari, Oromo, Sidama, Shanqella etc., the inhabitants were enslaved and

heavily taxed by the gebbar system leading to

depopulation

Menelik brought together many of the northern

territories through political consensus. The exception was Gojjam,

which offered tribute to the Shewan Kingdom following its defeat at

the Battle of Embabo. Most of the western

and central territories like Jimma, Welega Province and Chebo surrendered to Menelik's invading forces with

no resistance. Native armed soldiers of Ras Gobana Dacche, Ras Mikael Ali, Habtegyorgis Dinegde, Balcha Aba Nefso and

were allied to Menelik's Shewan army which campaigned to the south to

incorporate more territories.

Beginning in the 1870s, Menelik set off from the

central province of Shewa to reunify 'the lands and people of the

South, East, and West into an empire. This period of expansions has been

referred to by some as the 'Agar Maqnat' - roughly

translating to some type of 'Cultivation' of land. The people incorporated

by Menelik through conquest were the southerners – Oromo, Sidama,

Gurage, Wolayta and other groups. Historian Raymond

Jonas describes the conquest of the Emirate of Harar by Menelik as

"brutal".

In territories incorporated peacefully like Jimma,

Leka, and Wolega the former order was preserved and

there was no interference in their self-government; in areas incorporated after

war, the appointed new rulers did not violate the peoples' religious beliefs

and they treated them lawfully and justly. However, in the territories

incorporated by military conquest, Menelik's army carried out atrocities

against civilians and combatants including torture, mass killings, and large

scale slavery.[ Large scale atrocities were also committed against

the Dizi people and the people of the Kaficho kingdom. Some estimates that the number of people killed as a result of the

conquest from war, famine and atrocities go into the millions. Based on

convergent subjugation approaches, cooperation between Menelik and Belgian

king Leopold II were attempted more than once.

Foundation of Addis Ababa

The imperial flag of Menelik II. For a period,

Ethiopia lacked a permanent capital; instead, the royal encampment served as a

roving capital. For a time Menelik's camp was on Mount Entoto,

but in 1886, while Menelik was on campaign in Harar, Empress Taytu Betul camped at a hot spring to the south of

Mount Entoto. She decided to build a house there and

from 1887 this was her permanent base, which she named Addis

Ababa (new flower). Menelik's Generals were all allocated land nearby to

build their own houses, and in 1889 work began in a new royal palace. The

city grew rapidly, and by 1910 the city had around 70,000 permanent

inhabitants, with up to 50,000 more on a temporary basis. Only in 1917,

after Menelik's death, was the city reached by the railway from Djibouti.

The Great Famine (1888–1892)

During Menelik's reign, the great famine of 1888

to 1892, which was the worst famine in the region's history, killed a third of

the total population which was then estimated at 12 million. The famine

was caused by rinderpest, an infectious viral cattle disease which wiped

out most of the national livestock, killing over 90% of the cattle. The

native cattle population had no prior exposure and were unable to fight off the

disease.

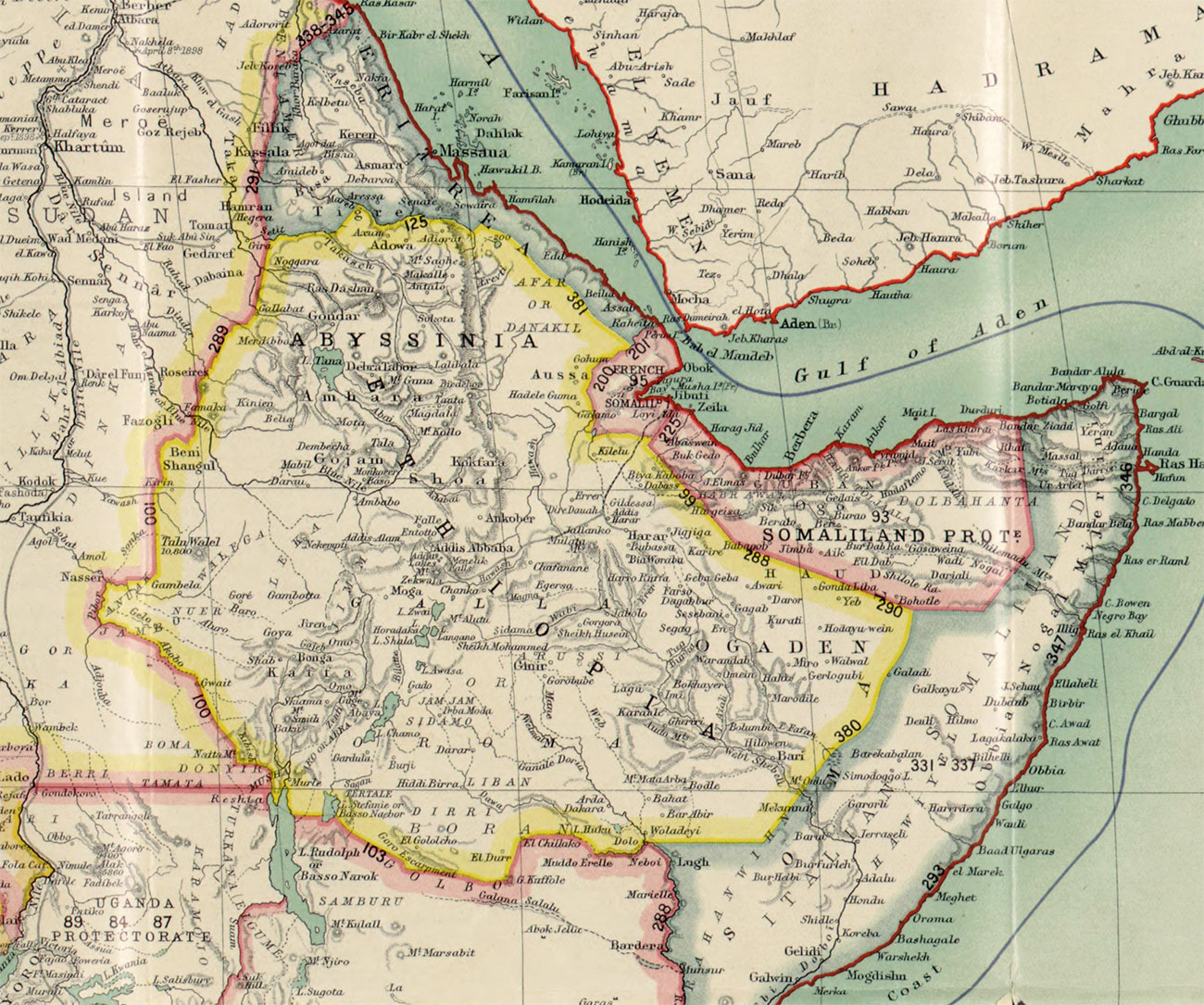

Wuchale Treaty Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in an 1891 map, showing national

borders before the Battle of Adwa On 2 May 1889, while claiming the throne

against Ras Mengesha Yohannes, the "natural son" of Emperor

Yohannes IV, Menelik concluded a treaty with Italy at Wuchale (Uccialli in

Italian) in Wollo province. On the signing of the

treaty, Menelik said "The territories north of the Merab

Milesh (i.e. Eritrea) do not belong to Abyssinia nor are under my

rule. I am the Emperor of Abyssinia. The land referred to as Eritrea is

not peopled by Abyssinians – they are Adals, Bejaa, and Tigres. Abyssinia

will defend his territories but will not fight for foreign lands, which Eritrea

is to my knowledge." Under the

Treaty, Abyssinia and Kingdom of Italy agreed to define the

boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia. For example, both Ethiopia and Italy

agreed that Arafali, Halai, Segeneiti and Asmara are

villages within the Italian border. Also, the Italians agreed not to harass

Ethiopian traders and to allow safe passage for Ethiopian goods, particularly

military weapons. The treaty also guaranteed that the Ethiopian government

would have ownership of the Monastery of Debre Bizen but

not use it for military purposes.

However, there were two versions of the treaty, one in

Italian and another in Amharic. Unknown to Menelik the Italian version gave

Italy more power than the two had agreed to. The Italians believed they had

"tricked" Menelik into giving allegiance to Italy. To their surprise,

upon learning about the alteration, Emperor Menelik II rejected the treaty. The

Italians attempted to bribe him with two million rounds of ammunition but he

refused. Then the Italians approached Ras Mengesha of Tigray in an attempt to create

civil war, however, Ras Mengesha, understanding that Ethiopia's independence

was at stake, refused to be a puppet for the Italians. The Italians, therefore,

prepared to attack Ethiopia with an army led by Baratieri.

Subsequently, the Italians declared war and attempted to invade Ethiopia.

Italo-Ethiopian War

Menelik's disagreement with Article 17 of the treaty

led to the Battle of Adwa. Before Italy could launch the invasion, Eritreans

rebelled in an attempt to push Italy out of Eritrea and prevent its invasion of

Ethiopia. The rebellion was not successful. However, some of the Eritreans

managed to make their way to the Ethiopian camp and jointly fought Italy at

the battle of Adwa.

On 17 September 1895, Menelik ordered all of the Ethiopian nobility to call out their banners and raise their feudal hosts, stating: "An enemy has come across the sea. He has broken through our frontiers in order to destroy our fatherland and our faith. I allowed him to seize my possessions and I entered upon lengthy negotiations with him in hopes of obtaining justice without bloodshed. But the enemy refuses to listen. He undermines our territories and our people like a mole. Enough! With the help of God I will defend the inheritance of my forefathers and drive back the invader by force of arms. Let every man who has sufficient strength accompany me. And he who has not, let him pray for us". Menelik's opponent,

General Oreste Baratieri, underestimated the

size of the Ethiopian force, predicating that Menelik could only field 30,000

men.

Despite the dismissive Italian claim that Ethiopia was a

"barbaric" African nation whose men were no match for white troops,

the Ethiopians were better armed, being equipped with thousands of modern

rifles and Hotchkiss artillery guns together with ammunition and shells which

were superior to the Italian rifles and artillery. Menelik had ensured that his

infantry and artillerymen were properly trained in their use, giving the

Ethiopians a crucial advantage as the Hotchkiss artillery could fire more

rapidly than the Italian artillery. In 1887 a British diplomat, Gerald Portal,

wrote after seeing the Ethiopian feudal hosts parade before him, the Ethiopians

were "...redeemed by the possession of unbounded courage, by a disregard

of death, and by a national pride, which leads them to look down on every human

being who has not had the good fortune to be born an Abyssinian

[Ethiopian]".

The Emperor personally led his army to attack an

Italian force led by Major Toselli on 7 December 1895 at Boota Hill. The

Ethiopians attacked a force of 350 Eritrean irregulars on the left flank, who

collapsed under the Ethiopian assault, causing Toselli to send two companies of

Italian infantry who halted the Ethiopian advance. Just as Toselli was

rejoicing in his apparent victory, the main Ethiopian assault came down on his

right flank, causing Toselli to order retreat. The Emperor's best

general, Ras Makonnen, had occupied the road leading back to Eritrea, and

launched a surprise attack, which routed the Italians. The battle of

Amba Alagi ended with an Italian force of 2,150 men losing 1,000 men and

20 officers killed.

Ras Makonnen followed up that victory by

defeating General Arimondi and forcing the Italians

to retreat to the fort at Mekele. Ras Makonnen

laid siege to the fort, and on the morning of 7 January 1896, the defenders of

the fort spotted a huge red tent among the besiegers, showing that the emperor

had arrived. On 8 January 1896, the emperor's elite Shoan infantry

captured the fort's well, and then beat off desperate Italian attempts to

retake the well. On 19 January 1896, the fort's commander, Major Galliano,

whose men were dying of dehydration, raised the white flag of surrender. Major

Galliano and his men were allowed to march out, surrender their arms and to go

free. Menelik stated he allowed the Italians to go free as "to give

proof of my Christian faith," saying his quarrel was with the Italian

government of Prime Minister Francesco Crispi that was trying to

conquer his nation, not the ordinary Italian soldiers who been conscripted

against their will to fight in the war. Menelik's magnanimity to the

defenders of Fort Mekele may have been an act of

psychological warfare. Menelik knew from talking to French and Russian

diplomats that the war and Crispi himself were unpopular in Italy, and one of

the main points of Crispi's propaganda were allegations of atrocities against

Italian POWs. From Menelik's viewpoint allowing the Italian POWs to go free and

unharmed was the best way of rebutting this propaganda and undermining public

support for Crispi.

Crispi sent another 15,000 men to

the Horn of Africa and ordered the main Italian commander, General Oreste Baratieri, to finish off the "barbarians". As Baratieri dithered, Menelik was forced to pull back

on 17 February 1896 as his huge host was running out of food. After Crispi

sent an insulting telegram accusing Baratieri of

cowardice, on 28 February 1896 the Italians decided to seek battle with

Menelik. On 1 March 1896, the two armies met at Adwa. The Ethiopians came

out victorious.

With victory at the Battle of Adwa and the

Italian colonial army destroyed, Eritrea was Emperor Menelik's for the taking

but no order to occupy was given. It seems that Emperor Menelik II was wiser

than the Europeans had given him credit for. Realising that the Italians would bring all their force to bear on his country if he

attacked, he instead sought to restore the peace that had been broken

by the Italians and their treaty manipulation seven years before. In signing

the treaty, Menelik II again proved his adeptness at politics as he promised

each nation something for what they gave and made sure each would benefit his

country and not another nation. Subsequently, the Treaty of Addis

Ababa was reached between the two nations. Italy was forced to recognise the absolute independence of Ethiopia, as

described in Article III of the treaty.

Developments during Menelik's reign

Following Menelik's victory at the First

Italo-Ethiopian War, the European powers moved rapidly to adjust relations with

the Ethiopian Empire. Delegations from the United Kingdom and France—whose

colonial possessions lay next to Ethiopia—soon arrived in the Ethiopian capital

to negotiate their own treaties with this newly proven power. Quickly taking

advantage of the Italian defeat, French influence increased markedly and France

became one of the most influential European powers in Menelik's court. In

December 1896, a French diplomatic mission in Addis Ababa arrived and on 20

March 1897 signed a treaty that was described as "véritable traité d'alliance. In turn,

the increase in French influence in Ethiopia led to fears in London that the

French would gain control of the Blue Nile and would be able to

"lever" the British out of Egypt.

On the eve of the Battle of Adwa, two Sudanese envoys

from the Mahdiyya state arrived at Menelik's camp in Adwa to

discuss concentrated action against the Italians. In July 1896 an Ethiopian

envoy was present at Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's court in Omdurman. The

British, fearing that Menelik would support the Mahdist revolt, sent a

diplomatic mission to Ethiopia and on 14 May 1897 signed

the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897. Menelik assured the British that he

would not support the Mahdists and declared them as the enemy of his country in

exchange for cession of the northeastern part of the Haud region,

a traditional Somali grazing area, to Ethiopia. In December 1897, Ras

Makonnen led an expedition against the Mahdists to seize the gold

producing region of Benishangul-Gumuz

Abolition of slave trading

By the mid-1890s, Menelik was actively suppressing

the slave trade, ordering the destruction of several slave

markets throughout the region and punishing slave traders with amputation. Both

Tewodros II and Yohannes IV had outlawed slave trading, but as not all tribes

were against it and as the country was surrounded on every side by slave

raiders and traders, it was not possible even at the dawn of the 20th century

to suppress the trade entirely. According to apologists, while Menelik

actively enforced his prohibition, it was beyond his power to change the minds

of all his people regarding the age-old practice.

Introducing new technology

After the Treaty of Addis Ababa was signed

in 1896, Europeans recognised the sovereignty of

Ethiopia. Menelik then finalised signing treaties

with Europeans to demarcate the border of modern Ethiopia by 1904 Menelik II

was fascinated by modernity, and like Tewodros II before him, he had a keen

ambition to introduce Western technological and administrative advances into

Ethiopia. Following the rush by the major powers to establish diplomatic

relations following the Ethiopian victory at Adwa, more and more westerners

began to travel to Ethiopia looking for trade, farming, hunting, and mineral

exploration concessions. Menelik II founded the first modern bank in

Ethiopia, the Bank of Abyssinia, introduced the first modern postal system,

signed the agreement and initiated work that established the Addis Ababa

–Djibouti railway with the French, introduced electricity to Addis Ababa, as

well as the telephone, telegraph, the motor car, and modern plumbing. He

attempted unsuccessfully to introduce coinage to replace the Maria Theresa

thaler.

In 1894, Menelik granted a concession for building the

Ethio-Djibouti Railways In 1894, Menelik granted a concession for the building

of a railway to his capital from the French port

of Djibouti but, alarmed by a claim made by France in 1902 to control

of the line in Ethiopian territory, he ordered a stop for four years on the

extension of the railway beyond Dire Dawa. In 1906 when France, the United

Kingdom, and Italy came to an agreement on the subject, granting control to a joint

venture corporation, Menelik officially reaffirmed his full sovereign rights

over the whole of his empire.

According to one persistent tale, Menelik heard about

the modern method of executing criminals using electric chairs during

the 1890s, and ordered 3 for his Kingdom. When the chairs arrived, Menelik

learned they would not work, as Ethiopia did not yet have an electric

power industry. Rather than waste his investment, Menelik used one of the

chairs as his throne, sending another to his second (Lique Mekwas)

or Abate Ba-Yalew. Recent research,

however, has cast significant doubt on this story, and suggested it was

invented by a Canadian journalist during the 1930s.

Personal life and death

Menelik reportedly spoke French, English and Italian

fluently. He read many books and was educated in finance, getting involved

in various investments, including in American railroads and American securities

and French and Belgian mining investments.

The British journalist Augustus B. Wylde wrote after

meeting Menelik: "I had found him a man of great kindness, a remarkably

shrewd and clever man and very well informed on most things except on England

and her resources; his information on our country evidently having been

obtained from persons entirely unfriendly to us; and who did not want

Englishmen to have any diplomatic or commercial transactions whatever with

Abyssinia [Ethiopia]".

After meeting him, Count Gleichen wrote:

"Menelik's manners are pleasant and dignified; he is courteous and kindly,

and at the same time simple in manner, giving one the impression of a man who

wishes to get at the root of a matter at once, without wasting time in

compliments and beating about the bush, so often the characteristics of

Oriental potentates...He also aims at being a popular sovereign, accessible to

his people at all hours, and ready to listen to their complaints. In this, he

appears to be quite successful, for one and all of his subjects seem to bear

for him a real affection."

Wives

Taytu Betul, the third wife of Menelik. Menelik married three times but he did not

have a single legitimate child by any of his wives. However, he is reputed to

have fathered several children by women who were not his wives, and

he recognized three of those children as being his progeny.

In 1864, Menelik married Woizero Altash Tewodros, whom he divorced in 1865; the marriage produced no children. Altash Tewodros was a daughter of Emperor Tewodros II. She

and Menelik were married during the time that Menelik was held captive by

Tewodros. The marriage ended when Menelik escaped captivity, abandoning her.

She was subsequently remarried to Dejazmatch Bariaw Paulos of Adwa.

In 1865, the same year as divorcing his first wife,

Menelik married the much older noblewoman Woizero Bafena Wolde

Michael. This marriage was also childless, and they were married for seventeen

years before being divorced in 1882. Menelik was very fond of his wife, but she

apparently did not have a sincere affection for him. Woizero Befana had several

children by previous marriages and was more interested in securing their

welfare than in the welfare of her present husband. For many years, she was

widely suspected of being secretly in touch with Emperor Yohannes IV in her

ambition to replace her husband on the throne of Shewa with one of her sons

from a previous marriage. Finally, she was implicated in a plot to overthrow

Menelik when he was King of Shewa. With the failure of her plot, Woizero Befana

was separated from Menelik, but Menelik apparently was still deeply attached to

her. An attempt at reconciliation failed, but when his relatives and courtiers

suggested new young wives to the King, he would sadly say "You ask me to

look at these women with the same eyes that once gazed upon Befana?",

paying tribute both to his ex-wife's beauty and his own continuing attachment

to her.

Finally, Menelik divorced his treasonous wife in 1882,

and in 1883, he married Taytu Betul. Menelik's

new wife had been married four times previously, and he became her fifth

husband. They were married in a full communion church service and the marriage

was thus fully canonical and indissoluble, which had not been the case with

either of Menelik's previous wives. The marriage, which proved childless, would

last until his death. Taytu Betul would become

Empress consort upon her husband's succession, and would become the most

powerful consort of an Ethiopian monarch since Empress Mentewab.

She enjoyed considerable influence on Menelik and his court until the end,

something which was aided by her own family background. Empress Taytu Betul was a noblewoman of Imperial blood and a

member of one of the leading families of the regions of Semien, Yejju in modern Wollo,

and Begemder. Her paternal uncle, Dejazmatch Wube Haile

Maryam of Semien, had been the ruler of Tigray and much of

northern Ethiopia. She and her uncle Ras Wube were

two of the most powerful people among descendants of Ras Gugsa Mursa, a ruler of Oromo descent from the house of was

Sheik of Wollo. Emperor Yohannes was able to broaden

his power base in northern Ethiopia through Taytu's family connections in Begemider, Semien and Yejju; she also served him as his close adviser, and went

to the battle of Adwa with 5,000 troops of her own. From 1906, for all intents

and purposes, Taytu Betul ruled in Menelik's stead

during his infirmity. Menelik II and Taytu Betul

personally owned 70,000 slaves. Abba Jifar II also is said to have more than

10,000 slaves and allowed his armies to enslave the captives during a battle

with all his neighboring clans. This practice was common between various

tribes and clans of Ethiopia for thousands of years.

Taytu arranged political marriages between her Yejju and

Semien relatives and key Shewan aristocrates like Ras Woldegyorgis Aboye,

who was Governor of Kaffa, Ras Mekonen who was

governor of Harar, and Menelik's eldest daughter Zewditu Menelik who

became Nigeste Negestat of

the empire after the overthrow of Lij Iyasu. Taytu's step daughter, Zewditu, was married to her

nephew Ras Gugsa Welle who administered Begemider up to the 1930s.

Natural children

The emperor caricatured by Glick for Vanity

Fair (1897) Previous to his marriage to Taytu Betul, Menelik fathered several natural children. Among them, he

chose to recognise three specific children (two

daughters and one son) as being his progeny. These were:

A daughter, Woizero Shoaregga Menelik, born 1867. She would marry twice and become the mother of: A son, Abeto Wossen Seged Wodajo, born

of the first marriage; never considered for the succession due to dwarfism

A daughter, Woizero Zenebework Mikael, who was married at age twelve and died in childbirth one year later

A son, the purported Emperor Iyasu V. He

nominally succeeded upon Menelik's death in 1913, but was never crowned; he was

deposed in 1916 by powerful nobles.

A daughter, Woizero (later Empress) Zewditu

Menelik, born 1876, died 1930. She married four times and had some

children, but none of them survived to adulthood. She was proclaimed Empress in

her own right in 1916, but was a figurehead, with ruling power in the hands of

regent Ras Tafari Makonnen, who succeeded her in 1930 as

Emperor Haile Selassie.

A son, Abeto Asfa

Wossen Menelik, born 1873. He died unwed and childless when he was about

fifteen years of age.

Menelik's only recognised son, Abeto Asfa Wossen Menelik, died unwed and

childless when he was about fifteen years of age, leaving him with only two

daughters. The elder daughter, Woizero Shoaregga, was

first married to Dejazmatch Wodajo Gobena, the son of

Ras Gobena Dachi. They had a son, Abeto Wossen Seged Wodajo, but this grandson of Menelik II was

eliminated from the succession due to dwarfism. In 1892, twenty-five-year-old

Woizero Shoaregga was married for a second time to

forty-two-year-old Ras Mikael of Wollo. They had two

children, namely a daughter, Woizero Zenebework Mikael, who would be married at the age of twelve to the much older Ras Bezabih Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, and would die in childbirth a year later; and a

son, Lij Iyasu, who would nominally succeed

as Emperor after Menelik's death in 1913, but would never be crowned, and would

be deposed by powerful nobles in favour of Menelik's

younger daughter Zewditu in 1916.

Menelik's younger daughter, Zewditu Menelik, had

a long and chequered life. She was married four

times, and eventually became Empress in her own right, the first woman to hold

that position in Ethiopia since the Queen of Sheba. She was only ten years

old when Menelik got her married to Ras Araya Selassie Yohannes, the

fifteen-year-old son of Emperor Yohannes IV, in 1886. In May 1888, Ras Araya

Selassie died and Zewditu became a widow at age twelve. She was married two

more times for brief periods to Gwangul Zegeye and Wube Atnaf Seged before marrying Gugsa Welle in 1900. Gugsa Welle was the nephew of Empress Taytu Betul, Menelik's third wife. Zewditu had some

children, but none of them survived to adulthood. Menelik died in 1913, and his

grandson Iyasu claimed the throne on principle of seniority. However,

it was suspected that Iyasu was a secret convert to Islam, which was

the religion of his paternal ancestors, and having a Muslim on the throne would

have grave implications for Ethiopia in future generations.

Therefore, Iyasu was never crowned; he was deposed by nobles in 1916,

in favour of his aunt, Zewditu. However, Zewditu

(aged 40 at that time) had no surviving children (all her children had died

young) and the nobles did not want her husband and his family to exercise power

and eventually occupy the throne. Therefore, Zewditu's cousin Ras Tafari

Makonnen was named both heir to the throne and regent of the empire.

Zewditu had ceremonial duties to perform and wielded powers of arbitration and

moral influence, but ruling power was vested in the hands of regent Ras

Tafari Makonnen, who succeeded her as Emperor Haile Selassie in 1930.

Apart from the three recognised natural children, Menelik was rumoured to be the

father of some other children also. These include Ras Birru Wolde

Gabriel and Dejazmach Kebede Tessema. The

latter, in turn, was later rumoured to be the natural

grandfather of Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, the communist leader

of the Derg, who eventually deposed the monarchy

and assumed power in Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991.

Illness, death and succession

On 27 October 1909, Menelik II suffered a massive

stroke and his "mind and spirit died". After that, Menelik was no

longer able to reign, and the office was taken over by Empress Taytu, as de facto ruler, until Ras Bitwaddad Tesemma was publicly

appointed regent. However, he died within a year, and a council of regency

– from which the empress was excluded – was formed in March 1910.

Menelik's mausoleum. In the early morning hours

of 12 December 1913, Emperor Menelik II died. He was buried quickly without

announcement or ceremony at the Se'el Bet Kidane Meheret Church, on the grounds of the Imperial

Palace. In 1916 Menelik II was reburied in the specially built church at Ba'eta Le Mariam Monastery in Addis Ababa.

After the death of Menelik II, the council of regency

continued to rule Ethiopia. Lij Iyasu was never

crowned Emperor of Ethiopia, and eventually, Empress Zewditu

I succeeded Menelik II on 27 September 1916.

Legacy

The Adwa Victory Day is celebrated in March

annually, and it would also inspire Pan-African movements around the

globe.

Despite being generally considered the founder of

modern Ethiopia, Menelik's legacy also garnered controversies due to the

atrocities committed by his army against civilians and combatants during the

annexation of territories into his Empire, which are considered by many

historians as constituting genocide. According to Awol Allo:

The historical figure that masterminded the victory at

Adwa, Emperor Menelik II, also presided over some of the most brutal atrocities

committed against the various groups in the southern part of the country,

particularly the Oromos, as they resisted his southward expansion. For

Oromos, Menelik II is devil incarnate and is beyond redemption. Perhaps, the

association of Adwa with Menelik II is the single most important reason behind

Oromo ambivalence towards this historical event.

A desire to share in the glamor Menelik enjoyed after

his victory over Italy may explain an improbable Serb legend,

recounted by English anthropologist Mary E. Durham, portraying Menelik and

the Serb king of Montenegro as kinsmen, based on little more than the

similarity between the Ethiopian honorific Negus and the name of

the Herzegovinian village, Njegushi, from

which the Montenegrin royal family originated:

When these Herzegovinese migrated to Montenegro, a large body of them went yet farther afield and

settled in the mountains of Abyssinia, among them a branch of the family

of Petrovich of Njegushi, from which is directly

descended Menelik, who preserves the title of Negus and is a distant

cousin of Prince Nikola of Montenegro, and to this large admixture of

Slav blood the Abyssinians owe their fine stature and their high standard of civilisation, as compared with the neighbouring African tribes.

|