|

BIOGRAPHYCAL UNIVERSAL LIBRARY |

|

|

|

RICHARD THE LION HEART

BOOK I

RICHARD OF AQUITAINE

CHAPTER ITHE BOY DUKE1157-1179

“The eagle of the broken covenant shall rejoice

in her 1157 third nesting”—thus ran one of the predictions in the so-called

“prophecy of Merlin” which in the latter half of the twelfth century was

generally regarded as shadowing forth the destiny of Henry Fitz-Empress and his

family. “The queen” said those who interpreted the prophecy after the event,

“is called the eagle of the broken covenant because she spread out her wings

over two realms, France and England, but was separated from the one by divorce

and from the other by long imprisonment. And whereas her first-born son,

William, died in infancy, and the second, Henry, in rebellion against his

father, Richard, the son of her third nesting, strove in all things to bring

glory to his mother’s name”.

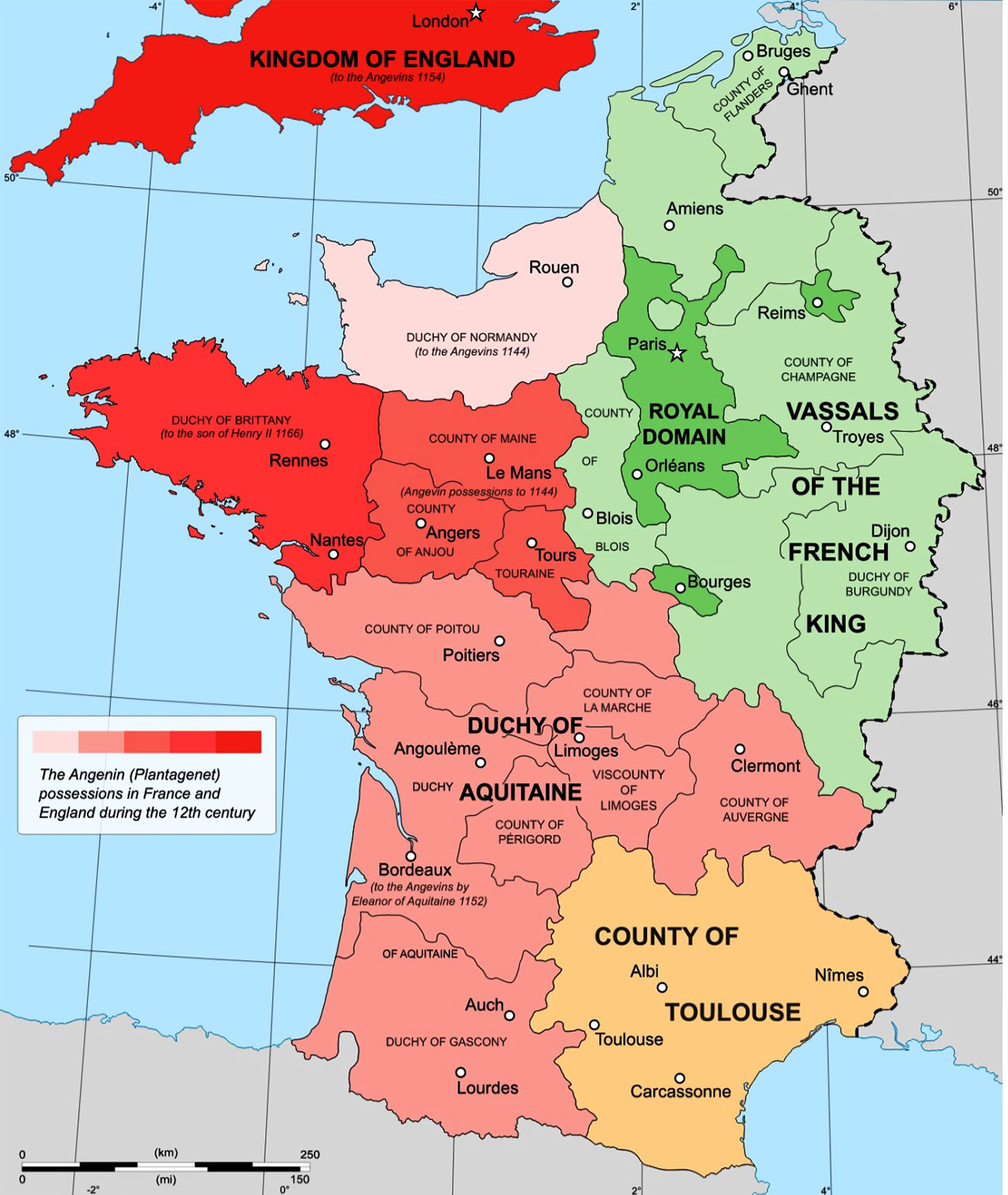

There was nothing to mar the rejoicing of

either Eleanor or Henry in September 1157. The young king had overcome the

difficulties which had beset him at the opening of his reign. Public order and

the regular administration of public justice had been restored throughout his

realm. He had obtained the French king’s recognition of his rights over

Normandy and the Angevin lands, and also over Eleanor’s duchy of, Aquitaine,

where in the winter of 1156 he had received the homage of the barons and kept

the Christmas festival with her at Bordeaux. King and queen 1157 returned to

England in the spring. Soon afterwards the last remnant of

opposition to the rule of the Angevin king in England had been disarmed in the

persons of Earl Hugh of Norfolk and Count William of Boulogne; Henry had

“subdued all the Welsh to his will” and received, together with the homage of

Malcolm of Scotland, a formal restitution of Northumberland, Westmorland and

Cumberland, which had been in the possession of the Scots since 1136. From

these successes Henry had either just returned, or was on his way back to

rejoin his queen at Oxford, when their third son was born there—no doubt in

Beaumont palace—on September 8. A woman of S. Alban’s was chosen for the boy’s

nurse and fostered him together with her own son, born on the same night and

afterwards known as Alexander Neckam, author of a

treatise on natural science or what passed for science in his time. Her name

was Hodierna; in later days she had from the royal

domains in Chippenham an annuity of seven pounds, doubtless granted to her by

her royal nursling, whom she seems to have survived by some twenty years. Whether

she dwelt at the court while he was under her charge, or whether, like 1157 his

ancestor Geoffrey Martel, he was sent to dwell with his foster-mother, there is

nothing to show. Before he was two years old his destiny was planned by the

king; Richard was to be heir to the dominions of his mother.

“Aquitaine” says an English writer of the

time, “abounding in riches of many kinds, excels other parts of the western

world in such wise that it is reckoned by historians as one of the happiest

and most fertile among the provinces of Gaul. Although its fields respond

abundantly to culture, its vines to propagation, and its woodlands to the

chase, yet nevertheless it takes its name not from any of these advantages, but

from its waters (aquae), haply esteeming as alone worthy of account among its

delights that which its health-giving water brings forth either to be returned

to the sea, or uplifted in the air. If, indeed, we track the Garonne from its

fount along its rapid course to the sea, and if we also follow the line of the

Pyrenean mountains, all the country that lies between derives its name from the

beneficent waters that flow through it. Furthermore, in those parts smoothness

of tongue is so general that it promises impunity to everybody, and any one who knows not the manner of that people cannot know

whether they are more constant in deed than in word. When they set themselves

to tame the pride of their enemies, they do it in earnest; and when the labours of battle are over and they settle down to rest in

peace, they give themselves up wholly to pleasure”.

Whatever may be thought of Dean Ralph’s

etymology, there was an element of truth in his description, half jesting

though it seems to be, of the country and the character of its people. He gives

indeed hardly sufficient prominence to the pugnacious side of the latter; and

the boundaries which he assigns to the former are considerably narrower than

those of the duchy of Aquitaine as it stood at the time of Richard’s birth.

That duchy comprised, in theory at least, fully one-third of the kingdom of

France. As counts of Poitou its dukes bore direct sway over a territory bounded

on the north by Britanny, Anjou, and Touraine, on the

west by the sea from the bay now known as that of Bourgneuf to the mouth of the Charente, and on the east (roughly) by the course of the

river Creuse from a little distance below Argenton to

its junction with the Vienne; and also over the dependent district of Saintonge

on the north side of the estuary of the Garonne, or Gironde. As counts of

Gascony they were overlords of a number of lesser counties and lordships,

extending from the mouth of the Garonne to the Pyrenees, and forming a

territory nearly twice the size of Poitou. Between Poitou and Gascony lay the

counties of Angouleme, La Marche, and Perigord, and,

between the two latter, a cluster of minor fiefs which collectively formed the

district known as the Limousin, and of which the most

important was the viscounty of Limoges. All these had from early times owned

the overlordship of the Poitevin counts in their

ducal capacity. So, too, had Berry, an extensive district lying to the north of

La Marche. The north-eastern portion of Berry, which formed the viscounty of

Bourges, had, however, for a long time past been lost to the dukes and reckoned

as part of the Royal Domain of France. On the eastern and south-eastern borders

of the duchy lay the counties of Auvergne and Toulouse. Toulouse, with its

dependencies—the Quercy or county of Cahors, Alby,

Foix, Carcassonne, Cerdagne and Roussillon—had always

been a separate fief held directly of the Crown; but the right to its ownership

had for the last sixty years been in dispute between the Poitevin counts and its actual holders, the house of St. Gilles, who also held the neighbouring county of Rouergue and with it the overlordship of a number of smaller fiefs along the southern

coast. Auvergne, originally a part of the Aquitanian duchy, was strongly

disposed to reject the authority of the Poitevin dukes; and both Auvergne and Toulouse were more or less openly supported in

this matter by the French king. Nor were 1157 the other underfiefs of the duchy, or even the barons of Poitou, by any means models of feudal

obedience. For a century or more the dukes had been periodically at strife with

the counts of Angouleme, the counts of La Marche, the lords of Lusignan (in

Poitou), the viscounts of Limoges, and the neighbours and rivals of these last. It was little more than twenty years since Count

William of Angouleme had carried off from Poitiers Eleanor’s stepmother, the

Countess Emma, “by the counsel of the chiefs of the Limousin who feared lest the Poitevin yoke should be laid more

heavily upon them” owing to her marriage with the duke, she being a daughter

and a possible co-heiress of the viscount of Limoges. At Limoges itself,

moreover, there seems to have been a perennial rivalry between the bishop, the

viscount, the abbot of the great abbey of S. Martial, and the townsfolk.

When Henry II went to Limoges after his

marriage in 1152 he seems to have been welcomed as duke by the viscount; but

strife arose between his followers and the citizens which so enraged him that

he ordered the recently built walls of the town to be razed and the bridge to

be destroyed. As the town—locally called “the castle”—was held by the viscount

of the abbot, this was an offence to all parties at once; and the abbot

retorted by refusing to grant the duke’s claim to a procuration in the

city—that is, outside the walls—saying he was only bound to grant it within the

enclosure of the “castle”. Henry, though angry, had his mind fixed on more

important matters, and let the insult pass; but on his next visit to Limoges,

in 1156, he successfully asserted his ducal rights. In the spring or early

summer of 1159 he again went to Aquitaine, to prosecute by force of arms his

claim, as Eleanor’s husband, to the county of Toulouse. The support of the Count

of Barcelona and his wife, the Queen of Aragon, was purchased by a promise that

Richard should wed their infant daughter and should on his marriage receive the

Dukedom of Aquitaine. The Quercy was conquered by

Henry and held for him awhile after he had abandoned the siege of Toulouse and

returned to Normandy. A treaty made between Henry and Louis of France in May

1160 contained a provision for a year’s truce between Henry and Raymond of

Toulouse, during which Henry was to keep whatever he at the date of the treaty

had of the honour of Toulouse, Cahors, or Quercy. This was

probably not much, as his troops had already been withdrawn from the conquered

territory; the greater part of it seems to have fallen back into Raymond’s

hands, and we hear nothing more of the relations between him and Henry for

nearly thirteen years.

Where and how the future duke of Aquitaine

was being brought up there is nothing to show. All that we know about him, till

he was well advanced in his thirteenth year, is that the sheriffs of London

paid ten pounds six and eightpence for his travelling expenses on some

occasion—probably his elder brother’s birthday feast—in 1163, and that in May

1165 he went with his mother and eldest sister to join the king in Normandy.

Henry’s quarrel with S. Thomas of Canterbury was then at its height; and

Henry’s discontented subjects in Aquitaine were quick to take advantage of the

opportunity for mischief given them by the difficulties with France in which

that quarrel involved him. On the pretext of “certain liberties whereof he had

deprived them” some of them became so troublesome—chiefly, it seems, by their

intrigues with King Louis—that in November 1166 he summoned them to a

conference at Chinon. It took place on Sunday,

November 19, with so little result that he sent Eleanor, who had apparently

been trying to maintain order in the duchy during his absence, back to England

and himself went to keep Christmas at Poitiers. Whether Richard went with his

mother or stayed with his father does not appear.

In March Henry had a conference with Raymond

of Toulouse at Grandmont. Shortly afterwards he tried

to assert his ducal authority over the count of Auvergne. The only result was a

fresh rupture with Louis, which was temporarily patched up by a truce made in

August to last till Easter next, March 31, 1168. Before that date a formidable

rebellion broke out in Aquitaine. The counts of Angouleme and La Marche, the

viscount of Thouars, Robert of Seilhac in the Limousin and his brother Hugh, Aimeric of Lusignan in Poitou, Geoffrey of Rancogne in the 1168 county of Angouleme, “with many

others,” sought to rebel against the king, and went about ravaging with fire

and sword. When the king heard of this he hurried to the place, took the strong

castle of Lusignan and made it stronger still, and destroyed the villages and

fortresses of the rebels.” He then revictualled his own castles, and left the

duchy under the charge of Eleanor (who had rejoined him after Christmas) and of

Earl Patrick of Salisbury, while he himself went to meet Louis on the Norman

border on April 7. The truce between the kings was now expired, and

Henry desired a treaty of peace; but meanwhile the southern rebels were urging

Louis to insist that Henry should indemnify them for the loss and damage which

he had inflicted upon them, and which they represented as a breach of his truce

with France, the French king being supreme lord of Aquitaine. They even placed

in the hands of Louis the hostages which they had promised to Henry. Louis did

not go to the conference in person, but sent some nobles to represent him. To

them Henry proposed a new scheme for the future of Aquitaine : that its young

duke-designate should marry the youngest daughter of Louis. The French envoys

refused to bind their sovereign to this unexpected condition; it was, however,

agreed “that if Richard should ask for

his rights over the Count of St. Gilles”—that is, of Toulouse—“the king of

France should try the cause in his court”. Thus the settlement of Aquitaine on

Richard was, by implication at least, recognized by France, although Richard

himself was not yet eleven years old. As to the aggrieved nobles, Henry

promised them restitution; but Louis would not give up the hostages; and the

conference ended in another truce to last till the octave of midsummer.

Scarcely had the parties separated when

tidings came that Earl Patrick had been slain in a fight with some of the

malcontents. Henry was too much overburdened with other cares to attempt during

the rest of that year any personal intervention in Aquitaine. Eleanor seems to

have urged him to make it formally over to Richard. She probably saw that there

was no likelihood of a good understanding between her people and her Angevin

husband, and hoped to be more successful in governing them herself in the name

of her son. Her suggestion, and that which Henry had made nine months before to

the representatives of Louis, were both carried into effect on January 6, 1169,

when the two kings made peace at Montmirail. The two

elder sons of Henry and Eleanor were both present at the meeting. Henry himself

first did homage to Louis for his continental possessions; young Henry did the

like for Britanny, Anjou and Maine; then Richard was

betrothed to the French king’s daughter Aloysia, and

likewise performed the homage due to Louis for the county of Poitou and the

duchy of Aquitaine. The feudal situation created by these transactions was a

strange one. It was capable of at least two different interpretations, and its

practical result, so far as Aquitaine was concerned, was that for the next

twenty years there were two dukes of that country. Henry’s purpose in thus

making his sons do homage to Louis was to guard against the possibility of

dispute, after his own death, as to the portion of his dominions to which each

of them was entitled. In his eyes the homage was anticipatory of a future and

perhaps—for he was not yet thirty-six—still very remote event, and its effect'

was merely prospective. But, so far as can be seen, no such limitation of its

scope was expressed in the act of homage; and the legal effect of that act

therefore was not merely prospective, but immediate; it at once made the

younger Henry and Richard respectively count of Anjou and duke of Aquitaine,

not under the suzerainty of their father, but under the direct overlordship of

the French king. Such at least would be its legal effect as soon as the boys

were old enough to govern for themselves; and this age young Henry had almost

reached, for he was in his fourteenth year. Their father, on the other hand, as

the sequel shows, never intended to give during his own lifetime any real

authority at all to young Henry, nor did he intend to give any to Richard

otherwise than with a tacit but perfectly well understood reservation of his

own right of intervention and control whenever he might choose to exercise it;

and he still remained legally both count and duke, for he had just repeated, in

both capacities, his own homage to Louis. There can be no doubt that Louis was

fully alive (although it seems that Henry was not) to the advantages which the

French Crown might derive from this complicated state of affairs. But he was,

of course, not desirous of pointing them out to his rival; and during the next

four years he carefully refrained from all interference with the affairs of the

Angevin dominions. The new duke of Aquitaine was, however, not yet twelve years

old, and it was clearly with the French king’s sanction that his father, in the

spring, marched into the duchy and forcibly brought the counts of Angouleme and

La Marche and most of the other rebels to submission.

Our only certain notice of Richard between

January 1169 and June 1172 shows him to

have been, at some time in 1170, at Limoges with his mother, laying the

foundation-stone of the abbey of S. Augustine. On the Octave of Whit-Sunday,

June 11, 1172, his formal installation as duke took place at Poitiers. In the

abbey church of S. Hilary he was placed, according to custom, in the abbot’s

chair, and the sacred lance and banner which were the insignia of the ducal

office were given to him by the Archbishop of Bordeaux and the Bishop of

Poitiers. He afterwards proceeded to Limoges, where he was received with a

solemn procession; the ring of S. Valeria, the protomartyr of Aquitaine, was

placed on his finger, and he was then proclaimed as “the new Duke”—for it was

in virtue of this double investiture, given not by the king of France, but by

the local prelates and clergy as representatives of the local saints of the

land, that the dukes of Aquitaine claimed to hold their dukedom.

Eight months later another important ceremony

took place at Limoges. Henry and Eleanor, accompanied by their two elder sons,

held court in the castle for a week with the kings of Aragon and Navarre, and

the counts of Toulouse and Maurienne. Alfonso of

Aragon, Raymond of Toulouse, and Humbert of Maurienne had met Henry at Montferrand in Auvergne, the

last-named to make a treaty of marriage between his daughter and Henry’s

youngest son, John, the two former to seek the king’s mediation in a quarrel

between themselves. Alfonso was the son of Queen Petronilla and Raymond of

Barcelona, and brother of the girl to whom Richard had been betrothed in 1159.

He and Raymond of Toulouse were at strife about the homage of Cerdagne, Foix, and Carcassonne; both were anxious for the

friendship of their nearest and most powerful neighbour.

Henry “made peace between them” and Raymond, whose territories were ringed in

by those of Aragon and Aquitaine, paid the peacemaker his price; “he became the

man of the king, and of the new king his son, and of Count Richard of Poitou,

to hold Toulouse of them”—that is, to hold it immediately of Richard, who held

it under his elder brother and his father—“as a hereditary fief, by military

service at the summons of either king or count, and by a yearly payment of a

hundred marks of silver or of ten destriers worth at least ten marks each.”

A few months later Richard entered actively

on public life; and he made a bad beginning. Towards the end of March the

younger King Henry fled from his father’s court in Normandy to that of Louis.

The elder Henry had been warned at Limoges by Raymond of Toulouse that “his

wife and his sons had formed a conspiracy against him”; but he had

disregarded the warning, and left Richard and Geoffrey in Aquitaine under the

guardianship of their mother. Early in the summer both the lads joined their

elder brother in France, and all three pledged themselves by a solemn oath, at

a great council in Paris, “not to forsake the king of France, nor to make any

peace with their father save through him (Louis) and the French barons”; Louis

in return swearing, and causing his barons to swear, “that he would help the

young king and his brothers, to the utmost of his power, to maintain their war

against their father and to gain possession of the kingdom of England for young

Henry”.

The “young king” was eighteen years old; he

was as shallow-minded and selfish as he was handsome and superficially

attractive; and he had fallen under the influence of Louis, to whose daughter

he was married. Crowned in 1170 as his father’s heir, he chose to consider

himself aggrieved by being given no share in the government of England or of

the Angevin homelands. He may have persuaded his brothers to consider themselves

as victims of a similar grievance with regard to their duchies of Aquitaine and Britanny. He and Louis were naturally anxious to

secure the forces of those two duchies in support of their scheme of ousting

the elder King Henry from his dominions, continental and insular; and they

hoped that the example of the boy-dukes might help to detach their respective

vassals from their father’s cause. But the lads had a nearer counsellor than

young Henry or Louis, and one to whose counsels it was only natural, and in a

measure right, that they should listen with reverence and submission. Eleanor

unquestionably sided with her elder son against her husband, for she was caught

in the act of trying to make her way from Aquitaine to the French court

disguised in the dress of a man. Certainly nothing can justify, or even excuse,

the duplicity of this “eagle of the broken covenant” towards the husband and

sovereign who, even when his eyes were fully opened to the treason of their

eldest son, still put such confidence in her loyalty as to leave the younger

eaglets in her charge. But there is a very considerable excuse for Richard and

Geoffrey. On the ground of that feudal loyalty which was a principle of such

importance in the life of those days, there was, indeed, something to be said

for all three of the brothers, and more especially for Richard. None of them

were homagers of Henry II; all of them were, homagers of Louis and of Louis alone. For Richard it might

further be urged that if he was under any other feudal obligation, it was more

to his mother than to his father; his possession of Aquitaine was their joint

gift, but it was on Eleanor’s consent that the validity of the gift really

rested; Henry possessed the dukedom only in right of his wife. On the higher ground

of filial duty Henry’s and Eleanor’s claims to the obedience of their children

were equal; Richard and Geoffrey suddenly found that those claims were

conflicting, and that a choice must be made between the two. That the choice

really lay between right and wrong is much plainer to us than it could be to

these lads, of whom the elder was not yet sixteen, and both of whom were under

the direct personal influence of their mother. On her, rather than on them,

lies the responsibility for their wrong choice.

Eleanor, captured by some of her husband’s

scouts, was at once placed by him in strict confinement. Her eldest son’s cause

gained practically nothing by the adhesion of his young brothers. According to

one account, both of them accompanied him to the siege of Drincourt in July. The success of that siege, however, was due, not to any of

the three, but to their allies the counts of Flanders and Boulogne; moreover,

the death of the latter soon afterwards caused the Flemish troops to withdraw

to their own country, and nothing further came of the expedition. The rebel

barons of Geoffrey’s duchy all submitted to his father in the autumn. At a

conference on September 25 at Gisors Henry made fair

offers to all three of his sons; “but the king of France did not deem it

advisable that the [English] king’s sons should make peace with their father.”

At some time before the end of the year Richard was knighted by Louis. Young

Henry and Geoffrey seem to have remained at the French court through the

winter, but Richard characteristically went his own way; he returned to

Aquitaine. Considering the extent of that country and the character of its

previous relations with Henry II, it seems to have furnished a very small

proportion of names to the list of avowed partizans of the young king; and the more important Aquitanian names which we do find

there are those of men whose disobedience is very unlikely to have been in any

way connected with that of Richard—Count William of Angouleme, Geoffrey of Rancogne, Geoffrey and Guy of Lusignan, William of Chauvigny, and Thomas of Coulonges in Poitou, Charles of Rochefort in Saintonge, Robert of Blé in the Limousin, and in Gascony Jocelyn of Maulay and Archbishop William of Bordeaux. The

first four of these needed no incitement from the young duke’s example, and the

last two are not likely to have been influenced by it, to throw off their

allegiance to his father. The Aquitanian rebels in 1173 would probably have

been more numerous had not the barons of the Limousin been at that time too busy fighting among themselves to give much heed to

disagreements between their rival rulers. The confusion in those parts was

aggravated by a swarm of “Brabantines,” or foreign

mercenaries, probably brought in by Henry at an earlier time, and now roving

about the land and preying on it wholly at their own will and pleasure. There

was no one to control either Brabantines or barons,

since Richard’s withdrawal and Eleanor’s imprisonment had left Aquitaine

without any resident governor at all, till in the winter Richard went back to

put himself single-handed at the head of affairs. We hear of him as far south

as Bordeaux, where he was no doubt sure of a welcome from Archbishop William,

and secured the support of another great churchman, the abbot of S. Cross, by confirming

the privileges of the abbey. He tried to win to his cause the rising town of La

Rochelle; but in this he failed; the townsfolk shut their gates in his face.

He soon, however, had under his command a considerable force of knights which at

Whitsuntide 1174 seized the city of Saintes. Henry was then at Poitiers; at the

head of a body of loyal Poitevins he marched upon

Saintes and drove out the intruders, and recovered possession of several other

rebel fortresses. The hopes of young Henry and Louis had broken down

both in Aquitaine and in Normandy. In England they broke down still more

completely; and the failure of the rebellion there led to the reopening of

negotiations for peace.

Some ten or fifteen years later a bitter

enemy of Henry II described the characters of young Henry and of Richard both

at once in the form of a comparison, or rather contrast, between them. The

contrast showed itself even in the ill-omened first stage of their political

and military careers. Throughout the rebellion of 1173-4 the young king was a

mere tool—and a very inefficient one—in the hands of Louis. At the instigation

of Louis he had entered upon the war, and at the dictation of Louis he was

ready to accept terms of peace. Geoffrey was apparently contented with a similar

position; but not so Richard. Eleanor might have made a tool of her second son,

but no one else could do so. It was not for love of either young Henry or Louis

that he had sided with them, and not at their behest would he give up the

struggle. On his seventeenth birthday the kings met at Gisors;

but “they could not come to a settlement because of the absence of Count

Richard, who at that time was in Poitou, making war on the castles and men of

his father”. The conference ended in a truce till Michaelmas,

on the understanding that meanwhile Henry should subdue Richard by force without hindrance from Louis, young

Henry, or their adherents. Richard was not yet hardened enough to contemplate

fighting his father in person; “when King Henry was come into Poitou, his son

Richard dared not await him, but fled from every place at his approach,

abandoning all the, fortresses that he had taken, not daring to hold them

against his father”. When he learned the terms of the truce, his indignation at

being thus deserted by his supposed allies made him suddenly determine on a

better course. “He came weeping, and fell with his face on the ground at the

feet of the king his father, beseeching his forgiveness”. It was granted

instantly and completely. Father and son re-entered Poitiers

together. At Henry’s suggestion Richard went in person to assure his elder

brother and Louis that he was no longer an obstacle to the conclusion of peace;

and on September 30 the peace was made at Montlouis in Touraine. Henry’s three sons placed themselves at his mercy and “returned to

him and to his service as their lord.” He promised to each of them a specified

provision; and they all pledged themselves to accept these provisions as final

and nevermore to require anything further from him save at his own pleasure,

nor to withdraw themselves or their service from him. Richard and Geoffrey also

did homage to him “for what he granted and gave them.” Young Henry would have

done likewise, but his father would not permit it “because he was a king.” This

treaty seems to have been afterwards put into writing and formally executed at

Falaise, probably on October 11. Early in 1175 Richard and Geoffrey

did homage to their father again at Le Mans, and on April 1 their elder brother

did the same at Bures.

The new provision for Richard did not include

his reinstatement as duke of Aquitaine or count of Poitou. It consisted merely

of “two fitting dwelling-places, whence no damage could come to the king, in

Poitou”, and half the revenues of that county in money. The strict letter of

the treaty of Montlouis (or of Falaise) in fact

reinstated Henry II as sole ruler of all the Angevin dominions, and reduced all

his sons to the position of dependents on his bounty. Henry, however, soon

showed that he had no intention of enforcing this punishment to the uttermost

on Richard and Geoffrey. The treaty ordained that all lands and castles

belonging to the king and his loyal barons were to be restored to their owners

and to the condition in which they had been fifteen days before “the king’s

sons departed from him”; so, too, were the lands of the rebels, but in their

case no mention was made of their castles. With these castles,

therefore, Henry was left free to deal at his pleasure. Accordingly, when early

in 1175 he set himself to carry out this clause of the treaty in Anjou and

Maine, he not only revictualled and repaired whatever fortresses of his own had

suffered damage, and destroyed whatever new fortifications had been added to

the castles whose owners had defied or resisted him, but also ordered that some

of these latter should be razed. Geoffrey was sent to carry out this process in Britanny, and Richard in Aquitaine, while the two

Henrys returned to England together on May 9.

Besides the avowed partizans of young Henry in Aquitaine, there were others who had seized the opportunity

afforded them by the war to fortify their castles and set the ducal authority

at defiance. The men of the South for the most part would at any moment gladly

have flung off that authority altogether, no matter whether it was wielded by

the heiress of the old ducal house, her husband, or her son. The Aquitanian

barons whose castles had in the time of the war been fortified or held against

Henry II made it clear that they were not disposed to give them up to Richard.

He therefore, in pursuance of his father’s orders, set out “to reduce the said

castles to nothing”. He began after midsummer by marching into the county of Agen, where Arnald of Bonville

had fortified Castillon against him, “and would not

give it up.” This place, fortified by both nature and art, held out against the

duke and his engines of war for nearly two months; at last he took it, and in

it thirty knights whom he kept in his own hands. We have no certain knowledge

of his further movements till the following spring, When he and Geoffrey of Britanny went to England together. They landed on Good

Friday, April 7. Richard’s purpose seems to have been to seek counsel and help

in the difficult task which his father had assigned to him, for when the Easter

festivities were over it was arranged by the elder Henry that the younger one

should go with Richard into Poitou “to subdue his enemies.” Young Henry went to

Normandy on April 20; Richard probably returned about the same time, though the

brothers did not cross the Channel together. During his absence Vulgrin of Angouleme, a son of the reigning count William Taillefer, had “presumed” to march into Poitou at the head

of a troop of Brabantines. The bishop of Poitiers had

at once resolved, with Theobald Chabot, who was the leader of Duke Richard’s

soldiery, to deliver the people committed to him out of the hand of their

enemies, and the invaders, although they far outnumbered the forces of the

bishop and the constable, had been completely routed near Barbezieux.

Richard made straight for Poitou and called out its feudal levies, and a great

multitude of knights from the regions round about flocked to him, for the wages

that he gave them. He began by punishing some of the rebels in Poitou; next,

after Whitsuntide (May 23), he marched against Vulgrin’s Brabantines and defeated them in a pitched battle

between St. Maigrin and Bouteville,

near the western border of the Angoumois. Thence he led his host into the Limousin, to punish Count Aimar of Limoges, who also had taken advantage of the duke’s absence to commit some

breaches of the peace. First, Richard besieged and took Aimar’s castle of Aixe with its garrison of forty knights.

Then he attacked Limoges, and in a few days was master of the city and all its

fortifications. All this was the work of a month. Shortly after midsummer he

returned to Poitiers; there he was at last joined by the young king. After

taking counsel with the Poitevin barons it was

decided that the next step should be the punishment of Vulgrin of Angouleme. The brothers led their united forces to Chateauneuf on the Charente, south-west of Angouleme, and won the place after a fortnight’s

siege. Thereupon young Henry would stay with his brother no longer, but

following evil counsel departed from him. Richard, thus suddenly deserted,

moved cautiously further away from Angouleme to Moulineuf,

another castle belonging to Vulgrin; this he captured

in ten days. Then he turned back again and laid siege to Angouleme itself.

Within its walls were not only Vulgrin and his

father, Count William, but also Aimar of Limoges and

two other rebel leaders, the viscounts of Ventadour and of Chabanais. In six days Count William was

forced to surrender into Richard’s hands himself, his city, and all its

contents, his castles of Bouteville, Archiac, Montignac, Jarnac, La Chaise, and Merpins,

and to give hostages for his submission to the mercy of Richard and of King

Henry, to whom Richard immediately sent him and the other nobles who had

surrendered with him. They presented themselves before Henry at Winchester on

September 21, fell at his feet, and obtained mercy from him; that is to say,

he, it seems, sent them back again with instructions that they should be

temporarily reinstated in their possessions, pending a fuller consideration

which he purposed to give to their case when he should return to Normandy.

Having for the moment reduced northern

Aquitaine to subjection, Richard set himself to a like task in Gascony. After

keeping Christmas at Bordeaux he marched upon Dax, which had been fortified

against him by its viscount with the help of the count of Bigorre.

Its recovery by Richard was quickly followed by that of Bayonne, held against

him by its viscount Ernald Bertram. Thence he marched

up to the very “Gate of Spain”—St. Pierre de Cize, on

the Navarrese border at the foot of the Pyrenees—took the castle of St. Pierre

in one day, razed it, compelled the Basques and Navarrese to swear that they

would keep the peace, “destroyed the evil customs which had been introduced at Sorde and Lesperon” (two towns in

the Landes) “where it was customary to rob pilgrims

on their way to or from S. James”, and by Candlemas was back at Poitiers,

having—for the moment—restored all the provinces to peace. The count of Bigorre in the south and a few barons of Saintonge and of

the Limousin had not yet submitted; Richard, however,

made no further movement against any of them for many months. His inaction may

have been due to instructions from his father, who was probably unwilling to

let him engage in another campaign against these rebels at a moment when all

the available forces of the Angevin house and the presence of Richard himself

seemed likely to be needed in another quarter.

The richest baron of Aquitanian Berry, Ralf

of Déols, the lord of Chateauroux, whose lands were

said to be worth as much as the whole ducal domains of Normandy, had died at

the close of 1176 leaving as his sole heir a daughter three years old. The

wardship of this child and of her heritage belonged of right to her

suzerain, the Duke of Aquitaine; but her relations were resolved to keep, if

possible, both herself and her lands in their own power, so they carried her

off to La Chatre, and prepared her castles and their

own for defence and defiance. When these tidings

reached King Henry in England, he sent urgent orders to his eldest son to

assemble the Norman host without delay and take forcible possession of the

lands of Déols. Henry’s action in this matter is

noticeable as showing that he regarded Richard’s tenure of the dukedom of

Aquitaine at this period as merely nominal or delegated; he claimed Denise of Déols as his own vassal, not as Richard’s. It is, however,

not at once apparent why, since he had intrusted to

Richard the task of subduing the other Aquitanian rebels, he did not leave the

affair of Déols to the same hands. The reason may

have been mainly a geographical one. These things may have taken place at a

moment when Henry knew Richard to be busily engaged at the very opposite end of

the duchy, at any rate somewhere in Gascony, perhaps at its extreme southern

border. The young king, on the other hand, was in Normandy, whence it would be

easy for him to lead a force through Maine and Touraine into Berry. On

receiving his father’s instructions he did so, and laid siege to Chateauroux,

which surrendered to him at once. He did not, however, gain possession of the

little heiress or of the rest of her lands; for the matter now became

complicated by the intervention of the supreme lord of Berry and of Aquitaine,

King Louis.

For more than eight years, ever since January

1169, Aloysia of France had been in Henry’s

guardianship as the destined bride of Richard. According to one of the best

informed English writers of the time, Louis, when this engagement was made, had

promised that on the marriage of the young couple he would make over to

Richard, as Aloysia’s dowry, the city of Bourges with

all its appurtenances; that is, the portion of Berry the ownership of which

was in dispute between France and Aquitaine. Ten years before—in the year of Aloysia’s birth—he had promised to King Henry a like

cession of the Vexin, the disputed borderland of

France and Normandy, as the dowry of Aloysia’s sister

Margaret on her intended marriage with Henry’s eldest son, and Henry had taken

advantage of the ambiguous wording of a clause in the treaty to have the two

children—contrary to Louis’s intention—at once formally married in church;

whereby he gained immediate possession, not indeed of the whole Vexin, but of that portion of it which had once been Norman

and which contained its most valuable fortresses, these being surrendered to

him by the Templars, who were by the treaty to have them in custody till the

marriage should take place. That marriage, nevertheless, had brought more

advantage to Louis than to Henry, by bringing Margaret’s husband, as soon as he

reached manhood, under the influence of his father-in-law in opposition to his

own father. There was but too much reason to fear a like result in the case of

Richard; and the dangers of such a result were even greater in this case than

in the former one, owing to special circumstances connected with the betrothal

of Richard and Aloysia. That betrothal was the price,

or part of the price, paid by Henry at Montmirail in

1169 for Louis’s sanction, as overlord, to the scheme devised by Henry for

securing a certain distribution of his dominions among his sons. Henry’s own

renewal of homage to Louis on that occasion for all his continental territories

was a token that he did not intend to renounce his personal rights over any of

his lands, but merely to secure for himself the power of sharing those rights

with his sons whenever he might choose to do so, and for the boys an

unquestionable right of succession at his death to their respective shares of

the Angevin heritage. But, somewhat like Louis nine years before, Henry made a

mistake which rendered it possible for his adversary to put another

construction upon the matter. He secured young Henry’s claims to the future

possession of the heritage of Geoffrey of Anjou and Maud of Normandy, and

Richard’s claim to the heritage of Eleanor, by making them do homage to Louis

for Anjou and Aquitaine respectively; but he omitted to secure the

subordination of their claims to his own during his lifetime by making them do

homage to himself. Owing to this omission, it was open to Louis to assert, if

he chose, that the Angevin counties and the Norman duchy legally belonged to

young Henry and the duchy of Aquitaine to Richard, in virtue of the homage

rendered by them for those lands direct to himself as .overlord; Henry II—so he

might argue—having by his consent to that homage tacitly renounced all claim to

the lands for which it was rendered, and being thenceforth merely in temporary

charge of them as guardian of the boys. The promise of the cession of Bourges

was a very small price to pay for a weapon so tremendous as that which Henry

had thus, it seems, unconsciously placed in the hands of an enemy whose mean

jealousy and unscrupulous astuteness he appears never to have fully realized.

He unintentionally made this possible construction of the treaty of Montmirail still more plausible through the crowning of his

eldest son in 1170 and the solemn installation of the second as duke of

Aquitaine in 1172. Louis acted upon it in 1173, although he does not seem ever

to have put it into formal words; and his action, coupled with that of the

ungrateful sons urged on by their mother, must have opened Henry’s eyes to the

peril in which he had involved himself through his misplaced confidence in the

loyalty both of his overlord and of his own family. It showed that as soon as

Richard and Aloysia were married, Louis might and in

all probability would demand the recognition of his new son-in-law as sole

ruler of Aquitaine, independent of any superior save Louis himself.

At the close of 1175 or early in 1176 Louis,

it seems, reminded Henry that, Richard being now in his nineteenth year and Aloysia in her sixteenth, it was full time for the contract

of marriage between them to be carried into effect; but the answer which he

received was so unsatisfactory that he referred the matter to the Pope. We have

no actual record of any communication between the kings on the subject at this

time, but something of the kind must have taken place to cause the Pope’s

action. In May 1176 Alexander bade Cardinal Peter, then legate in France, lay

the whole of Henry’s lands on both sides of the sea under Interdict “unless he

(Henry) would permit Richard and Aloysia to be

married without delay.” The legate, however, seems to have done nothing in the

matter for more than a year. Probably the two kings were negotiating; but we

hear nothing of their negotiations till June 1177, when Henry sent an embassy

to France to convene Louis about the dowries which he had promised to give with

his two daughters to the young king and to Richard—to wit, the Vexin (that is, its eastern or French part, which was still

in Louis’s hands) and the viscounty of Bourges. It seems that Henry,

having found Margaret’s marriage fail to give him the control over her promised

lands, demanded to be put in possession of those of Aloysia before he would allow her to marry Richard. But meanwhile the Pope had in May

renewed the injunctions which he had issued to Cardinal Peter eleven months

before; and on July 12 the English envoys returned with the news that Peter was

instructed to lay the whole of their sovereign’s dominions, insular and

continental, under Interdict, unless Richard were at once permitted to take for

his wife the maiden whom Henry “had so long already, and longer than had been

agreed, had in his custody for the said Richard.” Henry at once made the

English bishops appeal to the Pope. Illness detained him in England for nearly

five weeks; then he went to Normandy (August 18), and on September

21 met Louis and the legate at Nonancourt. In the

legate’s presence he promised that Richard should wed Aloysia,

if Louis gave Bourges to Richard and the Vexin to the

young king as previously agreed. Whether the wedding or the cession was to take

place first, however, seems to have been left an open question; and four days

later the whole matter was again postponed indefinitely by a treaty whereby the two elder kings pledged themselves to take the Cross and go to the Holy

Land together, and meanwhile, as brother Crusaders, to lay aside all mutual

strife and make no claims or demands upon each other’s possessions as they held

them at that moment, except with regard to Auvergne and to any encroachments

which the men of either party might have made upon those of the other in the

territory of Chateauroux or of the lesser fiefs on the border of their

respective lands in Berry. If on these excepted matters they could not agree

between themselves, twelve arbitrators were to decide according to the sworn

evidence of the men of the lands in question.

All immediate danger of interference from

either Louis or the Legate being thus removed, Henry summoned the Norman host

to meet at Argentan on October 9 for an expedition

against the rebels in Berry. Young Henry and Richard had, by his desire, joined

him on his arrival in Normandy; the former was now despatched in advance into Berry, and when the king’s host reached the Norman border at

Alençon Richard was detached from it and once more sent into Poitou to subdue

the enemies there, while the king himself marched upon Chateauroux. After

receiving its formal surrender he proceeded to La Châtre;

this place, and the little Lady of Déols, were also

given up to him at once. Thence he proceeded into the Limousin and called upon those of its nobles and knights who had taken part in the

rebellion of 1173 to give an account of their conduct; one of the most

important of them, the viscount of Turenne, surrendered his chief castle, “strongly

fortified by both art and nature with the others Henry dealt according as each of them deserved. He then

hurried back to Graçay in Berry, to meet Louis and

the commissioners who were to report to the two kings the result of their

investigations about Auvergne. What that result was we are nowhere directly

told; we only hear that both the rivals declared themselves content to abide by

it. The next reference to the overlordship of Auvergne, however, some twelve

years later, seems to indicate that the commissioners gave their award in favour of the duke of Aquitaine.

Another of Henry’s vassals in Berry, Odo of Issoudun, had lately died

leaving an infant heir, and this child had been stolen by his kinsman the duke

of Burgundy. The custody of his fief was offered to the king by the barons who

had it in their keeping, but he refused to receive it without the child, whom

he made no attempt to reclaim. It was not worth while to risk an embroilment with Burgundy about a petty lordship in Berry at the

moment when an opportunity was just presenting itself for annexing to the Poitevin domains a valuable fief of the duchy of Aquitaine,

the county of La Marche, which lay between Berry and the Limousin.

Count Adalbert V of La Marche had separated from his wife, lost his only son,

and seemingly disinherited his only daughter with her own consent; the kinship

between him and his only other surviving relatives was so remote that he deemed

himself free to dispose of his county without regard to them; and he now

offered to sell it to its overlord, King Henry, for a sum of money wherewith he

himself might go to end his lonely days in the Holy Land. In December Henry

went to meet him at Grandmont; the bargain was

quickly struck, the conveyance executed, and the purchase money—less than a

third of what Henry is said to have estimated the county as worth—paid down,

and the barons and knights of La Marche did homage to Henry as their immediate

liege lord.

In all these proceedings of Henry in

Aquitaine there is no reference to Richard. They clearly indicate that the

elder holder of the ducal title still claimed the ducal power and authority as

his own, not his son’s. He seems, however, to have left to Richard the

punishment of one important Limousin rebel whose case

he had a year before expressly reserved for his own judgement; for it was

Richard who now took away the castle’—that is, the fortified town—at Limoges

where S. Martial rests in his minster from the viscount; and it served the

viscount right, adds a Norman chronicler, for helping the count of Angouleme

against the duke. This seems to have been about the time when Henry was in

Aquitaine, and it is the only act of Richard’s mentioned by any chronicler

between Henry’s arrival in Normandy in August 1177 and his return to England in

July 1178. We may infer, almost with certainty, that it was done by

Henry’s order; and, with considerable probability, that the unusual state of

quiescence in which Richard seems to have passed these eleven months was due in

part at least to the restraint placed on him by Henry’s presence on the

continent. So long as Richard remained in the dependent position to which he

had been reduced by the agreement at Montlouis, it

would be impossible for him to take any considerable military or political

action, unless by his father’s order, while his father was within reach.

But in the autumn of 1178, when Henry was

once more in England, Richard’s activity recommenced. With a great host he again proceeded into Gascony as far as

Dax. There, to his delight, he found that the count of Bigorre,

who two winters before had helped the viscount of Dax to hold the city against

the duke, had somehow incurred the displeasure of the citizens and was fast in

their prison. They seem to have handed him over to Richard; but King Alfonso of

Aragon, grieving that his friend the count of Bigorre was held in chains, came to the said duke, and entreating that his friend might

be liberated, stood surety for him that he would do the will of the duke and of

his father the king of England; and the count of Bigorre,

that he might be set free, gave up to the duke Clermont and the castle of Montbron. Richard then went northward again, and after

keeping Christmas at Saintes gathered another great host for the subjugation of

Saintonge and the Angoumois. These two districts had been for years, and indeed

for generations, a seed-plot of rebellion. Richard seems to have been bent upon

reducing them to order once for all. The moving spirits of defiance there were Vulgrin of 1178 Angouleme and Geoffrey of Rancogne. Count William of Angouleme, after being

re-instated by Henry in his capital city, seems to have made over the

government of his county to his eldest son, Vulgrin,

who had headed the resistance to Richard in 1176. Geoffrey of Rancogne took his name from a place in the same county, and

was also owner of two lordships of far greater importance in Saintonge, one of

which, Pons, lay close to the border of the Angoumois, and the other, Taillebourg, was a fortress of great strength, about half

way between Saintes and St. Jean d’Angely. It was to

Pons that Richard now laid siege. After some weeks, finding that he made no

progress, he left his constables there with a part of his forces, and led the

rest, in Easter 1179 week (April 1-8), into the Angoumois. A three days’ siege

won the castle of Richemont; four other castles—Genzac, Marcillac, Gourville, Auville—were taken in the last fortnight of April and

levelled with the ground. Then he turned westward again, recrossed the border,

and marched upon Taillebourg.

By Richard’s contemporaries the siege of Taillebourg was looked upon as a most desperate enterprize, which none of his predecessors had ever

ventured to attempt. Never before had a hostile force so much as looked upon

the castle. It seems indeed to have been not merely a castle but a strongly

fortified, though small, town, the castle proper—perched on the summit of a

rock of which three sides were inaccessible by nature and the fourth was defended

by art—forming the citadel. “Girt with a triple ditch; defying from behind a

triple wall every external authority; amply secured with weapons, bolts, and

bars; crowned with towers placed at regular intervals; furnished with a handy

stone laid ready for casting from every loophole; well stocked with victuals;

filled with a thousand men ready for fight,” this virgin fortress “was in no

wise affrighted” at the duke’s approach. Richard, however, had made up his mind

to subdue the pride of Geoffrey of Rancogne once for

all. He had collected auxiliaries from every quarter; and he set them all to

work as soon as the host reached Geoffrey’s border. He carried off the wealth

of the farms; he cut down the vines; he fired the villages; whatever was left

he pulled down and laid waste; and then he pitched his tents on the outskirts

of the castle close to the walls, to the great alarm of the townsfolk, who had

expected nothing of the kind. At the end of a week (May 1-8), deeming it a

disgrace that so many high-spirited and well-proved knights should tamely

submit to be shut up within the walls, they agreed to sally forth and fall upon

the duke’s host at unawares. But the duke bade his men fly to arms, and forced

the townsmen to retire. The mettle of horses, the worth of spears, swords, helmets,

bows, arbalests, shields, mailcoats, stakes, clubs,

were all put to proof in the stubborn fight that raged at the gates, till the

townsmen could no longer withstand the fierce onslaught of the duke’s van

headed by the duke himself. As they retired helter-skelter within the walls, he

by a sudden dash made his way with them into the town. The citadel now became

their only refuge from their assailants, who rushed about the streets

plundering and burning at their will. Two days later—on Ascension Day, May 10—the

castle was surrendered, seemingly by Geoffrey in person; and in a few days more

the whole of its walls were levelled with the ground.

The capture of Taillebourg was Richard’s first great military exploit. It laid the foundation of his

military fame, not so much by the intrinsic importance of the exploit itself as

by the revelation, in the campaign of which it was at once the turning-point

and the crown, of the character and capability of the young duke. Its immediate

result was the complete submission of the rebels against whom that campaign was

directed. Not only did Geoffrey of Rancogne surrender

Pons, but Vulgrin of Angouleme, before the end of the

month, gave up his capital city and his castle of Montignac;

and when Richard, after razing the walls of all these places, sailed for

England, he left in Aquitaine, for the moment at least, all things settled

according to his will. He seems to have visited the tomb of S. Thomas the

Martyr at Canterbury before joining his father. Henry received him with great honour and gave him his reward; when the young conqueror

returned to Aquitaine shortly before Michaelmas, he

returned not merely as his father’s lieutenant, but as once again, with his

father’s sanction, count of Poitou.

BOOK I. RICHARD OF AQUITAINE , 1157-1189CHAPTER IIFATHER AND SONS1179-1183

|

|

|