|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

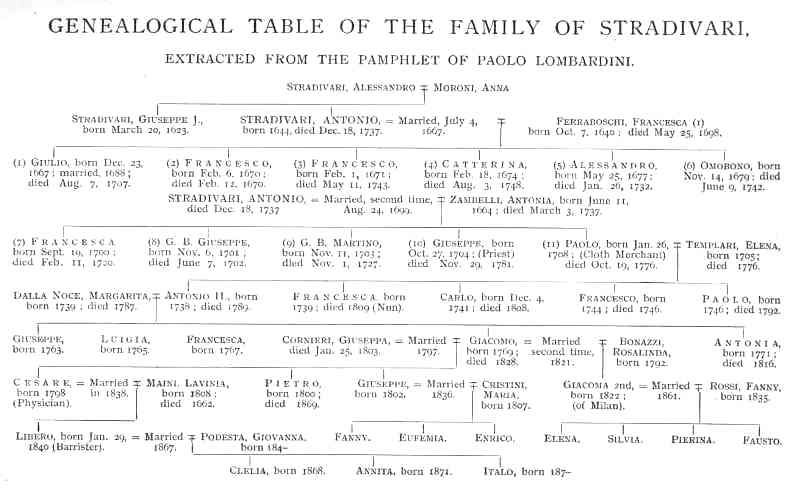

SECTION III The Italian School The fifteenth century

may be considered as the period when the art of making instruments

of the Viol class took root in Italy, a period rich in men labouring

in the cause of Art. The long list of honoured names connected with

Art in Italy during the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries

is a mighty roll-call indeed! The memory dwells upon the number

of richly-stored minds that have, within the limits of these three

centuries, bequeathed their art treasures to all time; and if here

we cannot suppress a comparison of the art world of the present

Italy with that of the periods named, still less can we fail to

be astonished as we discover the abyss into which Italy must be

judged to have sunk in point of merit, when measured by the high

standard which in former days she set herself. But perhaps the greatest

marvel of all is the rapidity of the decadence when it once set

in, as it did immediately after the culminating point of artistic

fame had been reached.

To reflect for a

moment upon the many famous men in Italy engaged in artistic vocations

contemporary with the great Viol and Violin makers cannot fail to

be interesting to the lovers of our instrument, for it has the effect

of surrounding their favourite with an interest extending beyond

its own path. It also serves to make prominent the curious fact

that the art of Italian Violin-making emerged from its chrysalis

state when the painters of Italy displayed their greatest strength

of genius, and perfected itself when the Fine Arts of Italy were

cast in comparative darkness. It is both interesting and remarkable

that the art of Italian Violin-making—which in its infancy

shared with all the arts the advantage attending the revival of

art and learning—should have been the last to mature and die. Whilst the artist,

scientist, and musician, Leonardo da Vinci, was painting, inventing,

and singing his sonnets to the accompaniment of his Lute; whilst

Raphael was executing the commands of Leo X., and Giorgio was superintending

the manufacture of his inimitable majolica ware, the Viol-makers

of Bologna were designing their instruments and assimilating them

to the registers of the human voice, in order that the parts of

Church and chamber madrigals might be played instead of sung, or

that the voices might be sustained by the instruments. If we turn to the

days of Gasparo da Sal�, Maggini, and Andrea Amati, we find that

while they were sending forth their Fiddles, Titian was painting

his immortal works, and Benvenuto Cellini, the greatest goldsmith

of his own or any age, was setting the jewels of popes and princes,

and enamelling the bindings of their books. Whilst the master-minds

of Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri del Ges� were occupied

with those instruments which have caused their names to be known

throughout the civilised world (and uncivilised too,

for many thousands of Violins are yearly made into which their cherished

names are thrust, after which they are despatched for the negro's

use), Canaletto was painting his Venetian squares and canals, Venetians

whose names are unrecorded were blowing glass of wondrous form and

beauty. At the same time, in the musical world, Corelli was writing

his jigs and sarabands, Geminiani penning one of the first instruction

books for the Violin, and Tartini dreaming his "Sonata del

Diavolo"; and while Guadagnini and the stars of lesser magnitude

were exercising their calling, Viotti, the originator of a school

of Violin-playing, was writing his concertos, and Boccherini laying

the foundation of classical chamber-music of a light and pleasing

character. It would be easy to continue this vein of thought, were

it not likely to become irksome to the reader; enough has been said

to refresh the memory as to the flourishing state of Italian art

during these times. What a mine of wealth was then opened up for

succeeding generations! and how curious is the fact that not only

the Violin, but its music, has been the creature of the most luxurious

age of art; for in that golden age musicians contemporary with the

great Violin-makers were writing music destined to be better understood

and appreciated when the Violins then made should have reached their

maturity. That Italy's greatest

Violin-makers lived in times favourable to the production of works

possessing a high degree of merit, cannot be doubted. They were

surrounded by composers of rare powers, and also by numerous orchestras.

These orchestras, composed mainly of stringed instruments, were

scattered all over Italy, Germany, and France, in churches, convents,

and palaces, and must have created a great demand for bow instruments

of a high class. The bare mention

of a few of the names of composers then existing will be sufficient

to bring to the mind of the reader well versed in musical matters

the compositions to which they owe their fame. In the sixteenth

century, Orlando di Lasso, Isaac, and Palestrina were engaged in

writing Church music, in which stringed instruments were heard;

in the seventeenth, lived Stradella, Lotti, Bononcini, Lully, and

Corelli. In the eighteenth century, the period when the art of Violin-making

was at its zenith, the list is indeed a glorious one. At this point

is the constellation of Veracini, Geminiani, Vivaldi, Locatelli,

Boccherini, Tartini, Viotti, Nardini, among the Italians; while

in France it is the epoch of Leclair and Gavini�s, composers of

Violin music of the highest excellence. Surrounded by these men

of rare genius, who lived but to disseminate a taste for the king

of instruments, the makers of Violins must certainly have enjoyed

considerable patronage, and doubtless those of tried ability readily

obtained highly remunerative prices for their instruments, and were

encouraged in their march towards perfection both in design and

workmanship. Besides the many writers for the Violin, and executants,

there were numbers of ardent patrons of the Cremonese and Brescian

makers. Among these may be mentioned the Duke of Ferrara, Charles

IX., Cardinal Ottoboni (with whom Corelli was in high favour), Cardinal

Orsini (afterwards Pope Benedict XIII.), Victor Amadeus Duke of

Savoy, the Duke of Modena, the Marquis Ariberti, Charles III. (afterwards

Charles VI., Emperor of Germany), and the Elector of Bavaria, all

of whom gave encouragement to the art by ordering complete sets

of stringed instruments for their chapels and for other purposes.

By the aid of such valuable patronage the makers were enabled to

centre their attention on their work, and received reward commensurate

with the amount of skill displayed. This had the effect of raising

them above the status of the ordinary workman, and permitted them

as a body to pass their lives amid comparative plenty. There are,

without doubt, instances of great results obtained under trying

circumstances, but the genius required to combine a successful battle

with adversity with high proficiency in art is indeed a rare phenomenon.

Carlyle says of such minds: "In a word, they willed one thing,

to which all other things were subordinate, and made subservient,

and therefore they accomplished it. The wedge will rend rocks, but

its edge must be sharp and single; if it be double, the wedge is

bruised in pieces, and will rend nothing." It may, therefore,

be affirmed that the greatest luminaries of the art world have shone

most brightly under circumstances in keeping with their peaceful

labours, it not being essential to success that men highly gifted

for a particular art should have this strength of will unless there

were immediate call for its exercise. Judging from the

large number of bow-instrument makers in Italy, more particularly

during the seventeenth century, we should conclude that the Italians

must have been considered as far in advance of the makers of other

nations, and that they monopolised, in consequence, the chief part

of the manufacture. The city of Cremona became the seat of the trade,

and the centre whence, as the manufacture developed itself, other

less famous places maintained their industry. In this way there

arose several distinct schools of a character marked and thoroughly

Italian, but not attaining the high standard reached by the parent

city. Notwithstanding the inferiority of the makers of Naples, Florence,

and other homes of the art as compared with the Cremonese, they

seem to have received a fair amount of patronage, the number of

instruments manufactured in these places of lesser fame being considerable. To enable the reader

to understand more readily the various types of Italian Violins,

they may be classed as the outcome of five different schools. The

first is that of Brescia, dating from about 1520 to 1620, which

includes Gasparo da Sal�, Maggini, and a few others of less note.

The next, and most important school, was that of Cremona, dating

from 1550 to 1760, or even later, and including the following makers:

Andrea Amati, Girolamo Amati, Antonio Amati, Niccol� Amati, Girolamo

Amati, son of Niccol�; Andrea Guarneri, Pietro Guarneri, Giuseppe

Guarneri, the son of Andrea; Giuseppe Guarneri ("del Ges�"),

the nephew of Andrea; Antonio Stradivari, and Carlo Bergonzi. Several

well-known makers have been omitted in the foregoing list simply

because they were followers of those mentioned, and therefore cannot

be credited with originality of design. The makers of Milan and

Naples may be braced together as one school, under the name of Neapolitan,

dating from 1680 to 1800. This school contains makers of good repute,

viz., the members of the Grancino family, Carlo Testore, Paolo Testore,

the Gagliano family, and Ferdinando Landolfi. The makers of Florence,

Bologna, and Rome may likewise be classed together in a school that

dates from 1680 to 1760, and includes the following names: Gabrielli,

Anselmo, Tecchler, and Tononi. The Venetian school, dating from

1690 to 1764, has two very prominent members in Domenico Montagnana

and Santo Seraphino; but the former maker may, not inappropriately,

be numbered with those of Cremona, for he passed his early years

in that city, and imbibed all the characteristics belonging to its

chief makers. Upon glancing at

this imposing list of makers, it is easy to understand that it must

have been a lucrative trade which in those days gave support to

so many; and, further, that Italy, as compared with Germany, France,

or England at that period, must have possessed, at least, more makers

by two-thirds than either of those three countries. And this goes

far to prove, moreover, that the Italian makers received extensive

foreign patronage, their number being far in excess of that required

to supply their own country's wants in the manufacture of Violins.

Roger North, in his "Memoirs of Musick," evidences the

demand for Italian Violins in the days of James II. He remarks:

"Most of the young nobility and gentry that have travelled

into Italy affected to learn of Corelli, and brought home with them

such favour for the Italian music, as hath given it possession of

our Parnassus. And the best utensil of Apollo, the Violin,

is so universally courted and sought after, to be had of the best

sort, that some say England hath dispeopled Italy of Violins."

We also read of William Corbett, a member of the King's band, having

formed about the year 1710 a "gallery of Cremonys and Stainers"

during his residence in Rome. Brescia was the cradle

of Italian Violin-making, for the few makers of bowed instruments

(among whom were Gaspard Duiffoprugcar, who established himself

at Bologna; Dardelli, of Mantua; Linarolli and Maller, of Venice)

cannot be counted among Violin-makers. The only maker, therefore,

of the Violin of the earliest date, it remains to be said, was Gasparo

da Sal�, to whom belongs the credit of raising the manufacture of

bowed instruments from a rude state to an art. There may be something

in common between the early works of Gasparo da Sal� and Gaspard

Duiffoprugcar, but the link that connects these two makers is very

slight, and in the absence of further information respecting the

latter as an actual maker of Violins, the credit of authorship must

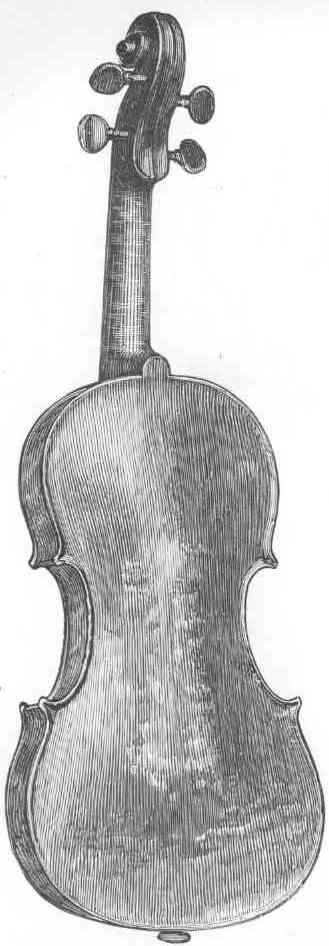

certainly belong to Gasparo da Sal�. We are indebted to

Brescia for the many grand Double-basses and Tenors that were made

there by Gasparo da Sal� and Maggini. These instruments formed the

stepping-stones to Italian Violin-making, for it is evident that

they were in use long before the first era of the Violin. The Brescian

Violins have not the appearance of antiquity that is noticeable

in the Double-basses or Tenors, and for one Brescian Violin there

are ten Double-basses, a fact which goes far to prove that the latter

was the principal instrument at that time.

From Brescia came

the masters who established the School of Cremona. The Amatis took

the lead, their founder being Andrea Amati, after whom each one

of the clan appears to have gained a march on his predecessor, until

the grand masters of their art, Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe

Guarneri del Ges�, advanced far beyond the reach of their fellow-makers

or followers. The pupils of the Amati, Stradivari, and Guarneri

settled in Milan, Florence, and other cities previously mentioned

as centres of Violin-making, and thus formed the distinct character

or School belonging to each city. A close study of the various Schools

shows that there is much in common among them. A visible individuality

is found throughout the works of the Italian makers, which is not

to be met with in anything approaching the same degree in the similar

productions of other nations. Among the Italians, each artist appears

to have at first implicitly obeyed the teaching of his master, afterwards,

as his knowledge increased, striking out a path for himself. To

such important acts of self-reliance may be traced the absolute

perfection to which the Italians at last attained. Not content with

the production of instruments capable of producing the best tone,

they strove to give them the highest finish, and were rewarded,

possibly beyond their expectation. The individuality noticed as

belonging in a high degree to Italian work is in many instances

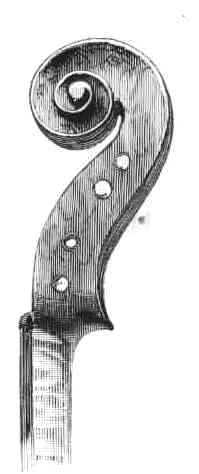

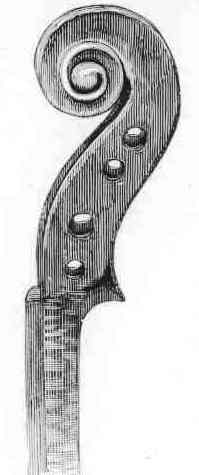

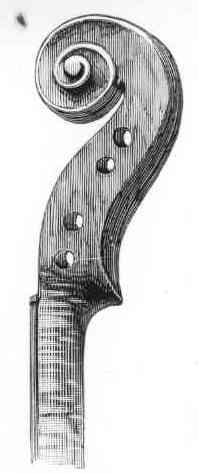

very remarkable. How characteristic the scroll and the sound-hole

of each several maker! The work of master and pupil differs here

in about the same degree as the handwriting of father and son, and

often more. Although Stradivari was a pupil of Niccol� Amati, yet

how marked is the difference between the scrolls and sound-holes

of these two makers; Carlo Bergonzi worked with Stradivari, yet

the productions of these two are more easily known apart. A similarly

well-defined originality is found, in a more or less degree, to

pervade the entire series of Italian Violins, and forms a feature

of much interest to the connoisseur. In closing my remarks

upon the Italian School of Violin-making, I cannot withhold from

the reader the concluding sentences of the Cremonese biographer,

Vincenzo Lancetti, as contained in his manuscript relative to the

makers of Cremona. He says: "I cannot help but deeply deplore

the loss to my native city (where for two centuries the manufacture

of stringed instruments formed an active and profitable trade) of

the masterpieces of its renowned Violin-makers, together with the

drawings, moulds, and patterns, the value of which would be inestimable

to those practising the art. Is it not possible to find a citizen

to do honour to himself and his city by securing the collection

of instruments, models, and forms brought together by Count Cozio

di Salabue, before the treasure be lost to Italy? I have the authority

of Count Cozio to grant to such a patron every facility for the

purchase and transfer of the collection, conditionally that the

object be to resuscitate the art of Violin-making in Cremona, which

desire alone prompted the Count in forming the collection."

These interesting remarks were written in the year 1823, with a

view to their publication at the end of the account of Italian Violin-makers

which Lancetti purposed publishing. As the work did not see the

light, the appeal of the first writer on the subject of Italian

Violins was never heard. Had it been, in all probability Cremona

would at this moment have been in possession of the most remarkable

collection of instruments and models ever brought together, and

be maintaining in at least some measure the prestige belonging to

its past in Violin-making. A word or two must

be said upon the famous varnish of the Italians, which has hitherto

baffled all attempts to solve the mystery of its formation. Every

instrument belonging to the school of Cremona has it, more or less,

in all its marvellous beauty, and to these instruments the resolute

investigator turns, promising himself the discovery of its constituent

parts. The more its lustre penetrates his soul, the more determined

become his efforts. As yet, however, all such praiseworthy researches

have been futile, and the composition of the Cremonese varnish remains

a secret lost to the world—as much so as the glorious ruby

lustre of Maestro Giorgio, and the blue so coveted by connoisseurs

of china. Mr. Charles Reade truly says: "No wonder, then, that

many Violin-makers have tried hard to discover the secret of this

varnish: many chemists have given anxious days and nights to it.

More than once, even in my time, hopes have run high, but only to

fall again. Some have even cried 'Eureka' to the public; but the

moment others looked at their discovery and compared it with the

real thing, 'Inextinguishable

laughter shook the skies.' At last despair has

succeeded to all that energetic study, and the varnish of Cremona

is sullenly given up as a lost art." Declining, therefore,

all speculation as to what the varnish is or what it is not, or

any nostrums for its re-discovery, we will pass on at once to the

description of the different Italian varnishes, which may be divided

into four distinct classes, viz., the Brescian, Cremonese, Neapolitan,

and Venetian. These varnishes are quite separable in one particular,

which is, the depth of their colouring; and yet three of them, the

Brescian, Cremonese, and Venetian, have to all appearance a common

basis. This agreement may be accounted for with some show of reason

by the supposition that there must have been a depot in each city

where the varnish was sold in an incomplete form, and that the depth

of colour used, or even the means adopted for colouring, rested

with the maker of the instrument. If we examine the Brescian varnish,

we find an almost complete resemblance between the material of Gasparo

da Sal� and that of his coadjutors, the colouring only being different.

Upon turning to the Cremonese, we find that Guarneri, Stradivari,

Carlo Bergonzi, and a few others, used varnish having the same characteristics,

but, again, different in shade; possibly the method of laying it

upon the instrument was peculiar to each maker. Similar facts are

observable in the Venetian specimens. The varnish of Naples, again,

is of a totally different composition, and as it was chiefly in

vogue after the Cremonese was lost, we may conclude that it was

probably produced by the Neapolitan makers for their own need. If we reflect for

a moment upon the extensive use which these makers made of the Cremonese

varnish, it is reasonable to suppose that it was an ordinary commodity

in their days, and that there was then no secret in the matter at

all. To account for its sudden disappearance and total loss is,

indeed, not easy. After 1760, or even at an earlier date, all trace

of it is obliterated. The demand for it was certainly not so great

as it had been, but quite sufficient to prevent the supply from

dying out had it been possible. The problem of its sudden disappearance

may, perhaps, be accounted for without overstepping the bounds of

possibility, if we suppose that the varnish was composed of a particular

gum quite common in those days, extensively used for other purposes

besides the varnishing of Violins, and thereby caused to be a marketable

article. Suddenly, we will suppose, the demand for its supply ceased,

and the commercial world troubled no further about the matter. The

natural consequence would be non-production. It is well known that

there are numerous instances of commodities once in frequent supply

and use, but now entirely obsolete and extinct. While, however, our

attention has been mainly directed to the basis of the celebrated

varnish, it must not be supposed that its colouring is of no importance.

In this particular each maker had the opportunity of displaying

his skill and judgment, and probably it was here, if anywhere, that

the secret rested. The gist of the matter, then, is simply that

the varnish was common to all, but the colouring and mode of application

belonged solely to the maker, and hence the varied and independent

appearance of each separate instrument. With regard, however, to

the general question as to what the exact composition of the gum

was or was not, I shall hazard no further speculation, and am profoundly

conscious of the fact that my present guesses have gained no nearer

approaches to the re-discovery of the buried treasure. A description, however,

of the various Italian varnishes may not be inappropriate. The Brescian

is mostly of a rich brown colour and soft texture, but not so clear

as the Cremonese. The Cremonese is of various shades, the early

instruments of the school being chiefly amber-coloured, afterwards

deepening into a light red of charming appearance, later still into

a rich brown of the Brescian type, though more transparent, and

frequently broken up, while the earlier kinds are velvet-like. The

Venetian is also of various shades, chiefly light red, and exceedingly

transparent. The Neapolitan varnish (a generic term including that

of Milan and a few other places) is very clear, and chiefly yellow

in colour, but wanting the dainty softness of the Cremonese. It

is quite impossible to give such a description of these varnishes

as will enable the reader at once to recognise them; the eye must

undergo considerable exercise before it can discriminate the various

qualities; practice, however, makes it so sharp that often from

a piece of varnishing the size of a shilling it will obtain evidence

sufficient to decide upon the rank of the Violin. And here, before

we dismiss the subject of the varnish, another interesting question

occurs: What is its effect, apart from the beauty of its appearance,

upon the efficiency of the instrument? The idea that the varnish

of a Violin has some influence upon its tone has often been ridiculed,

and we can quite understand that it must appear absurd to those

who have not viewed the question in all its bearings. Much misconception

has arisen from pushing this theory about the varnish either too

far or not far enough. What seems sometimes to be implied by enthusiasts

is, that the form of the instrument is of little importance provided

the varnish is good, which amounts to saying that a common Violin

may be made good by means of varnishing it. The absurdity of such

a doctrine is self-evident. On the other hand, there are rival authorities

who attach no importance to varnish in relation to tone. That the

varnish does influence the tone there is strong proof, and to make

this plain to the reader should not be difficult. The finest varnishes

are those of oil, and they require the utmost skill and patience

in their use. They dry very slowly, and may be described as of a

soft and yielding nature. The common varnish is known as spirit

varnish; it is easily used and dries rapidly, in consideration of

which qualities it is generally adopted in these days of high pressure.

It may be described as precisely the reverse of the oil varnish;

it is hard and unyielding. Now a Violin varnished with fine oil

varnish, like all good things, takes time to mature, and will not

bear forcing in any way. At first the instrument is somewhat muffled,

as the pores of the wood have become impregnated with oil. This

makes the instrument heavy both in weight and sound; but as time

rolls on the oil dries, leaving the wood mellowed and wrapped in

an elastic covering which yields to the tone of the instrument and

imparts to it much of its own softness. We will now turn to spirit

varnish. When this is used a diametrically opposite effect is produced.

The Violin is, as it were, wrapped in glass, through which the sound

passes, imbued with the characteristics of the varnish. The result

is, that the resonance produced is metallic and piercing, and well

calculated for common purposes; if, however, richness of tone be

required, spirit-varnished instruments cannot supply it. From these

remarks the reader may gather some notion of the vexed question

of varnish in relation to tone, and be left to form his own opinion. The chief features

of the Italian School of Violin-makers having been noticed, it only

remains to be said that the following list of makers is necessarily

incomplete. This defect arises chiefly from old forgeries. Labels

used as the trade marks of many deserving makers have from time

to time been removed from their lawful instruments in order that

others bearing a higher marketable value might be substituted. In

the subjoined list will be found all the great names, and every

care has been taken to render it as complete as possible. Several

names given are evidently German, most of which belong to an early

period, and are chiefly those in connection with the manufacture

of Lutes and Viols in Italy. These are included in the Italian list,

in order to show that many Germans were engaged in making stringed

instruments in Italy, about the period when Tenor and Contralto

Viols with four strings were manufactured there—a circumstance

worthy of note in connection with the history of Viol and Violin

making in Italy, bearing in mind that four-string Viols were used

in Germany when Italy used those having six strings.

Italian Makers ABATI, Giambattista,

Modena, about 1775 to 1793. ACEVO, Saluzzo. Reference

is made in the "Biographie Universelle des Musiciens"

to this maker having been a pupil of Gioffredo Cappa, and M. F�tis

mentions his having seen a Viol da Gamba dated 1693 of this make,

which belonged to Marin Marais, the famous performer on the Viol. ALBANESI, Sebastiano,

Cremona, 1720-1744. The pattern is bold and the model flat. Although

made at Cremona, they do not properly belong to the school of that

place, having the characteristics of Milanese work. The varnish

is quite unlike that of Cremona. ALBANI, Paolo, Palermo,

1650-80. Is said to have been a pupil of Niccol� Amati. The pattern

is broad and the work carefully executed. ALESSANDRO, named

"Il Veneziano," 16th century. ALETZIE, Paolo, Munich,

1720-36. He made chiefly Tenors and Violoncellos, some of which

are well-finished instruments. The varnish is inferior, both as

regards quality and colour. The characteristics of this maker are

German, and might be classed with that school. ALVANI, Cremona.

Is said to have made instruments in imitation of those of Giuseppe

Guarneri. AMATI, Andrea, Cremona.

The date of birth is unknown. It is supposed to have occurred about

1520. M. F�tis gave this date from evidence furnished by the list

of instruments found in the possession of the banker Carlo Carli,

which belonged to Count Cozio di Salabue. Mention is made of a Rebec,

attributed to Andrea Amati, dated 1546. Upon reference to the MSS.

of Lancetti, I find the following account of the Rebec: "In

the collection of the said Count there exists also a Violin believed

to be by Andrea Amati, with the label bearing the date 1546, which

must have been strung with only three strings, and which at that

epoch was called Rebec by the French. The father of Mantegazza altered

the instrument into one of four strings, by changing the neck and

scroll." From these remarks we gather that the authorship of

this interesting Violin is doubtful. There is, however, some show

of evidence to connect Andrea Amati with Rebecs and Geigen, in the

notable fact that most of his Violins are small, their size being

that known as three-quarter, which was, I am inclined to believe,

about the size of the instruments which the four-stringed Violin

succeeded. As to the time when Andrea Amati worked, I am of opinion

that it was a little later than has hitherto been stated. We have

evidence of his being alive in the year 1611, from an entry recently

discovered in the register of the parish in which Andrea Amati lived,

to the effect that his second wife died on April 10, 1611, and that

Andrea was then living. The discovery of this entry (together with

many important and interesting ones to which I shall have occasion

to refer) we owe to the patience and industry of Monsignor Gaetano

Bazzi, Canon of the Cathedral of Cremona. Andrea Amati claims attention

not so much on account of his instruments, as from his being regarded

as the founder of the school of Cremona. There is no direct evidence

as to the name of the master from whom he learnt the art of making

stringed instruments. If his work be carefully examined, it will

appear that the only maker to whose style it can be said to bear

any resemblance is Gasparo da Sal�, and it is possible that the

great Brescian may have instructed him in his art. It is unfortunate

that there are no data for our guidance in the matter. These men

often, like their brothers in Art, the painters of olden times,

began to live when they were dead, and their history thus passed

without record. Andrea Amati may possibly have been self-taught,

but there is much in favour of the view given above on this point.

His early works are so Brescian in character as to cause them to

be numbered with the productions of that school. For a general designation

of the instruments of this maker the following notes may suffice.

The work is carefully executed. The model is high, and, in consequence,

lacks power of tone; but the Violins possess a charming sweetness.

The sound-hole is inelegant, has not the decision of Gasparo da

Sal�, although belonging to his style, and is usually broad. His

varnish may be described as deep golden, of good quality. His method

of cutting his material was not uniform, but he seems to have had

a preference for cutting his backs in slab form, according to the

example set for the most part by the Brescian makers. The sides

were also made in a similar manner, the wood used being both sycamore

and that known to makers as pear-tree. The instruments of Andrea

Amati are now very scarce. Among the famous instruments of this

maker were twenty-four Violins (twelve large and twelve small pattern),

six Tenors, and eight Basses, made for Charles IX., which were kept

in the Chapel Royal, Versailles, until October, 1790, when they

disappeared. These were probably the finest instruments by Andrea

Amati. On the backs were painted the arms of France and other devices,

with the motto, Pietate et Justitia. In the "Archives

Curieuses de l'Histoire de France," one Nicolas Delinet, a

member of the French King's band, appears to have purchased in 1572

a Cremona Violin for his Majesty, for which he paid about ten pounds—a

large sum, it must be confessed, when we think of its purchasing

power in the sixteenth century. Mr. Sandys, who cites this curious

entry, rightly conjectures it may have included incidental expenses.

No mention is made of the maker of the Violin in question; we find,

however, that in the collection of instruments which belonged to

Sir William Curtis there was a Violoncello having the arms of France

painted on the back, together with the motto above noticed. The

date of the instrument was 1572. We may therefore assume that the

Violin purchased by Nicolas Delinet in the same year was the work

of Andrea Amati, and belonged to the famous Charles IX. set. AMATI, Niccol�, Cremona,

brother of Andrea. Very little is known of this maker or of his

instruments. AMATI, Antonio and

Girolamo, sons of Andrea Amati, Cremona.There does not exist certain

evidence as to the date of the birth and death of Antonio Amati.

We have information of the dates on which his brother Girolamo died

in extracts from parish registers; also the date of his marriages,

which took place in the year 1576, and on May 24, 1584. By his second

wife, Girolamo had a family of nine children; the fifth child was

Niccol�, who became the famous Violin-maker. The mother of Niccol�

died of the plague on October 27, 1630, and her husband, Girolamo,

died of the same disease six days later, viz., November 2, 1630,

and was buried on the same day. Girolamo is described in the register

as "Misser Hieronimo Amati detto il leutaro della vic di S.

Faustino" (viz., maker to the Church). Vincenzo Lancetti states

that "Count Cozio kept a register of all the instruments seen

by him, from which it appeared that the earliest reliable date of

the brothers Amati is 1577, and that they worked together until

1628; that Antonio survived Jerome and made instruments until after

the year 1648—a fine Violin bearing the last-named date having

been recently seen with the name of Antonio alone." This information

serves in some measure to set at rest much of the uncertainty relative

to the period when these makers lived. These skilful makers produced

some of the most charming specimens of artistic work. To them we

are indebted for the first form of the instrument known as "Amatese."

The early efforts of the brothers Amati have many of the characteristics

belonging to the work of their father Andrea; their sound-hole is

similar to his, and in keeping with the Brescian form, and the model

which they at first adopted is higher than that of their later and

better instruments. Although these makers

placed their joint names in their Violins, it must not be supposed

that each bore a proportionate part of the manufacture in every

case; on the contrary, there are but few instances where such association

is made manifest. The style of each was distinct, and one was immeasurably

superior to the other. Antonio deviated but little from the teaching

of his father. The sound-holes even of his latest instruments partake

of the Brescian type, and the model is the only particular in which

it may be said that a step in advance is traceable; here he wisely

adopted a flatter form. His work throughout, as regards finish,

is excellent. Girolamo Amati possessed

in a high degree the attributes of an artist. He was richly endowed

with that rare power—originality. It is in his instruments

that we discover the form of sound-hole which Niccol� Amati improved,

and, after him, the inimitable Stradivari perfected. Girolamo Amati

ignored the pointed sound-hole and width in the middle portions

observable in his predecessor's Violins, and designed a model of

extremely elegant proportions. How graceful is the turn of the sound-hole

at both the upper and lower sections! With what nicety and daintiness

are the outer lines made to point to the shapely curve! Niccol�

Amati certainly improved even upon Girolamo's achievements, but

he did not add more grace; and the essential difference between

the instruments of the two is, that there is more vigour in the

sound-hole of Niccol� than that of his father Girolamo. The purfling of the

brothers Amati is very beautifully executed. The scrolls differ

very much, and in the earlier instruments of these makers are of

a type anterior to that of the bodies. Further, the varnish on the

earlier specimens is deeper in colour than that found on the later

ones, which have varnish of a beautiful orange tint, sparingly laid

on, and throwing up the markings of the wood with much distinctness.

The material used by these makers and the mode of cutting it also

varies considerably. In some specimens we find that they used backs

of the slab form; in others, backs worked whole; in others, backs

divided into two segments. The belly-wood is in every case of the

finest description. The tone is far more powerful than that of the

instruments of Andrea, and this increase of sound is obtained without

any sacrifice of the richness of the quality. AMATI, Niccol�, Cremona,

born December 3, 1596, died April 12, 1684. Son of Girolamo Amati.

It is gratifying in the notice of this famous Violin-maker to be

able to supply dates of his birth, marriage, and death. Niccol�

was christened on December 6, 1596. His marriage took place on May

23, 1645, and it is interesting to record that his pupil Andrea

Guarneri witnessed the ceremony, and signed the register. The information

recently supplied by Canon Bazzi of Cremona, relative to the pupils

and workmen of Niccol� Amati, who were duly registered in the books

of the parish of SS. Faustino and Giovita, is fraught with interest.

It seems to carry us within the precincts, if not into the workshop,

of the master. Andrea Guarneri heads the list in the year 1653,

age twenty-seven, and married; next comes Leopoldo Todesca, age

twenty-eight; and Francesco Mola, age twelve. In the following year

Leopoldo Todesca appears to have been the only name registered as

working with Amati. In the year 1666 we have the name Giorgio Fraiser,

age eighteen. In 1668 no names of workmen seem to have been registered.

In 1680 the name of Girolamo Segher appears, age thirty-four, and

Bartolommeo Cristofori, age thirteen. In 1681 another name occurs,

namely Giuseppe Stanza, a Venetian, age eighteen. In the following

year the only name entered was that of Girolamo Segher, age thirty-six.

Niccol� Amati was the greatest maker in his illustrious family,

and the finest of his instruments are second only to those of his

great pupil, Antonio Stradivari. His early efforts have all the

marks of genius upon them, and clearly show that he had imbibed

much of the taste of his father Girolamo. He continued for some

time to follow the traditional pattern of the instruments, with

the label of Antonius and Hieronymus Amati, and produced many Violins

of small size, of which a large number are still extant. He appears

to have laboured assiduously during these early years, with the

view of making himself thoroughly acquainted with every portion

of his art. We find several instances in which he has changed the

chief principles in construction (particularly such as relate to

the arching and thicknesses), and thereby shown the intention which

he had from the first of framing a new model entirely according

to the dictates of his own fancy. The experienced eye may trace

the successive steps taken in this direction by carefully examining

the instruments dating from about 1645 downwards. Prior to this

period, there is a peculiarly striking similarity in his work and

model to that of his father, but after this date we can watch the

gradual change of form and outline which culminated in the production

of those exquisite works of the art of Violin-making known as "grand

Amatis"—a name which designates the grand proportions

of the instruments of this later date. It may be said that the maker

gained his great reputation from these famous productions. They

may be described as having an outline of extreme elegance, in the

details of which the most artistic treatment is visible. The corners

are drawn out to points of singular fineness, and this gives them

an appearance of prominence which serves to throw beauty into the

entire work. The model is raised somewhat towards the centre, dipping

rather suddenly from the feet of the bridge towards the outer edge,

and forming a slight groove where the purfling is reached, but not

the exaggerated scoop which is commonly seen in the instruments

of the many copyists. This portion of the design has formed the

subject of considerable discussion among the learned in the Violin

world, the debatable points being the appearance of this peculiarity

and its acoustic effect. As regards the former question, the writer

of these pages feels convinced that the apparent irregularity is

in perfect harmony with the general outline of the great Amati's

instrument; and it pleases the eye. From the acoustical point of

view, it may be conceded that it does not tend to increase of power;

but, on the other hand, probably, the sweetness of tone so common

to the instruments of Niccol� Amati must be set to its credit; for,

in proportion as the form is departed from, the sweetness is found

to decrease. The sound-hole has all the character of those of the

preceding Amati, together with increased boldness; in fact, it is

a repetition of that of Girolamo, with this exception. The sides

are a shade deeper than those of the brothers Amati. The scroll

is exquisitely cut. Its outline is perhaps a trifle contracted,

and thus is robbed of the vigour which it would otherwise possess.

From this circumstance it differs from the general tenor of the

body, which is certainly of broad conception. The maker would seem

to have been aware of this defect, if we may judge from the difference

of form given to his earlier scrolls, as compared with those of

a later date, in which he seems to have attempted to secure increased

boldness, as more in keeping with the character of the body of the

instrument. It must be acknowledged, however, that these efforts

did not carry him far enough. The surface of the scroll is usually

inclined to flatness. The wood used by Niccol� Amati for his grand

instruments is of splendid quality, both as regards acoustical requirements

and beauty of appearance. The grain of some of his backs has a wave-like

form of much beauty, others have markings of great regularity, giving

to the instrument a highly finished appearance. The bellies are

of a soft silken nature, and usually of even grain. A few of them

are of singular beauty, their grain being of a mottled character,

which, within its transparent coat of varnish, flashes light here

and there with singular force. The colour of the varnish varies

in point of depth; sometimes it is of a rich amber colour, at others

reddish-brown, and in a few instances light golden-red. These, then, are

the instruments which are so highly esteemed, and which form one

of the chief links in the Violin family. The highest praise must

be conceded to the originator of a design which combines extreme

elegance with utility; and, simple as the result may appear, the

successful construction of so graceful a whole must have been attended

with rare ingenuity and persevering labour. Here, again, is evidence

of the master mind, never resting, ever seeking to improve—evidence,

too, that mere elaboration of work was not the sole aim of the Cremonese

makers. They designed and created as they worked, and their success,

which no succeeding age has aspired to rival, entitles them to rank

with the chief artists of the world. On the form of the

instrument known as the "grand Amati" Stradivari exerted

all the power of his early years; and the fruits of his labours

are, in point of finish, unsurpassed by any of his later works.

Where Niccol� Amati failed, Stradivari conquered; and particularly

is this victory to be seen in the scrolls of his instruments during

the first period, which are masterpieces in themselves. How bold

is the conception, how delicate the workmanship, what a marvel of

perfection the sound-hole! But as these Violins are noticed under

the head of "Stradivari," it is unnecessary to enter into

details here. Beside Stradivari, many makers of less importance

followed the "grand Amati" pattern, among whom may be

mentioned Jacobs, of Amsterdam, who takes a prominent place as a

copyist. The truthfulness of these copies, as regards the chief

portions of the instrument, is singularly striking, so much so,

indeed, as to cause them to be frequently mistaken for originals

by those who are not deeply versed in the matter. The points of

failure in these imitations may be cited as the scroll and sound-hole.

The former lacks ease, and seems to defy its author to hide his

nationality. The scroll has ever proved the most troublesome portion

of the Violin to the imitator. It is here, if anywhere, that he

must drop the mask and show his individuality, and this is remarkably

the case in the instance above mentioned. A further difference between

Amati and Jacobs lies in the circumstance that the latter invariably

used a purfling of whalebone. Another copyist of Amati was Grancino.

As the varnish which he used was of a different nature from that

of his original, his power of imitation must be considered to be

inferior to that of some others. Numerous German makers, whose names

will be found under the "German School," were also liege

subjects of Amati, and copied him with much exactness; so also,

last, but not least, our own countrymen, Forster, Banks, and Samuel

Gilkes. Lancetti, writing

of Niccol� Amati in 1823, says: "Some masterpieces by him still

remain in Italy, among which is the Violin dated 1668, in the collection

of Count Cozio. It is in perfect preservation, and for workmanship,

quality, and power of tone far surpasses the instruments of his

predecessors." The same writer remarks that "Niccol� Amati

put his own name to his instruments about 1640." It was upon

a Violoncello of this make that Signor Piatti played when he first

appeared at the concert of the Philharmonic Society, on June 24,

1844. The instrument had been presented to him by Liszt, and is

now in the possession of the Rev. Canon Hudson. In an entry in the

Cathedral Register at Cremona, the name of the wife of Niccol� Amati

is given as Lucrezia Paliari. The meagreness of accounts of a documentary

character in relation to the famous makers of Cremona naturally

renders every contribution of the kind of some value. The following

extract, taken from the State documents in connection with the Court

of Modena, serves to indicate the degree of esteem in which the

instruments of Niccol� Amati were held during his lifetime, in comparison

with those of his contemporary and pupil, Francesco Ruggieri. Tomaso

Antonio Vitali, the famous Violinist, who was the director of the

Duke of Modena's Orchestra, addressed his patron to this effect:

"Please your most Serene Highness, Tomaso Antonio Vitali, your

highness's most humble servant, bought of Francesco Capilupi, through

the agency of the Rev. Ignazio Paltrineri, for the price of twelve

doublons, a Violin, and paid such price on account of its having

the name inside of Niccol� Amati, a maker of great repute in his

profession. The petitioner has since found that this Violin has

been wrongly named, as underneath the label is the signature of

Francesco Ruggieri detto il Pero, a maker of less credit, whose

Violins do not scarcely attain the price of three doublons." Vitali

closes his letter with an appeal to the Duke for assistance to obtain

redress. AMATI, Girolamo,

Cremona, born 1649, third son of Niccol�. The labels which I have

seen in a Violin and a Tenor bear the name "Hieronymus Amati,"

and describe the maker as the son of Niccol�. He was born on February

26, 1649, married in 1678. In 1736 he, together with his family,

removed to another parish, as shown by the original extract from

the books of the Cathedral at Cremona, sent by Canon Manfredini

to Lancetti. Girolamo Amati died in the year 1740. There appears

to have been some doubt as to whether Girolamo Amati, the son of

Niccol�, made Violins, according to Lancetti. He says, "Those

seen with his label, dated between 1703 and 1723, were ascribed

by some to Sneider, of Pavia, and by others to J. B. Rogeri, of

Brescia." In a letter of Count Cozio di Salabue to Lancetti,

dated January 3, 1823, he states that "in May, 1806, Signor

Carlo Cozzoni gave an old Amati Violin for repair to the Brothers

Mantegazza, dealers and restorers of musical instruments, in Milan,

and upon their removing the belly they were pleased to discover,

written at the base of the neck, 'Revisto e coretto da me Girolamo

figlio di Niccol� Amati, Cremona, 1710.'" In some instances

the instruments of this maker do not resemble those of Niccol� Amati,

or indeed those of the Amati family. The sound-holes are straight,

and the space between them is somewhat narrow. In others there is

merit of a high order—the pattern is large, broad between

the sound-holes, and very flat in model, and resembling the form

of Stradivari rather than that of Amati. These differences are accounted

for by the fact made known by Lancetti, that the tools and patterns

of Niccol� Amati passed into the possession of Stradivari, and are

therefore included with those now in the keeping of Count Cozio's

descendant, the Marquis Dalla Valle. The varnish of Girolamo Amati

shows signs of decadence; in some instances, however, we find it

soft and transparent. The few which have this quality of varnish

I am inclined to think were made in the time of Niccol�, since the

instruments of a later date have a coating of varnish of an inferior

kind. This maker—as with the Bergonzis—seems, therefore,

to have been either ignorant of his parent's mode of making superior

varnish, or was unable to obtain the same kind or quality of ingredients.

With Girolamo closes the history of the family of the Amati as Violin-makers.

Girolamo had a son, Niccol� Giuseppe, born in 1684, who removed

with his father to another parish in 1736, as mentioned above, but

he was not a maker of Violins. AMBROSI, Pietro,

Rome and Brescia, about 1730. Average merit. The workmanship resembles

that of Balestrieri, as seen in the inferior instruments of that

maker. ANSELMO, Pietro,

Cremona, 1701. The instruments of this maker partake of the Ruggeri

character. The varnish is rich in colour and of considerable body.

Scarce. I have met with two excellent Violoncellos by this maker.

Anselmo is said to have worked also in Venice. ANTONIAZZI, Gaetano,

Cremona, 1860. The work is passable, but the form faulty. The sound-holes

are not properly placed. ANTONIO OF BOLOGNA

(Antonius Bononiensis). There is a Viol da Gamba by this maker at

the Academy of Music, Bologna. ANTONIO, Ciciliano,

an Italian maker of Viols. A specimen exists at the Academy of Bologna,

without date. ASSALONE, Gasparo,

Rome, 18th century. The model is high and the workmanship rough.

Thin yellow varnish. BAGONI, Luigi (or

Bajoni), Milan, from about 1840. Was living in 1876. BAGATELLA, Antonio,

Padua, made both Violins and Violoncellos, a few of which have points

of merit. He wrote a pamphlet in 1782 on a method of constructing

Violins by means of a graduated perpendicular line similar to Wettengel's;

but no benefit has been derived from it. BAGATELLA, Pietro,

Padua, is mentioned as a maker who worked about 1760. BALESTRIERI, Tommaso,

middle of the 18th century. Said to have been a pupil of Stradivari,

which is probable. The instruments of Balestrieri may be likened

to those of Stradivari which were made during the last few years

of his life, 1730-37. The form of both is similar, and the ruggedness

observable in the latter instruments is found, but in a more marked

degree, in those of Balestrieri. These remarks, however, must not

be considered to suggest that comparison can fairly be made between

these two makers in point of merit, but merely to point out a general

rough resemblance in the character of their works. The absence of

finish in the instruments of Tommaso Balestrieri is in a measure

compensated by the presence of a style full of vigour. The wood

which he used varies very much. A few Violins are handsome, but

the majority are decidedly plain. The bellies were evidently selected

with judgment, and have the necessary qualities for the production

of good tone. The varnish seems to have been of two kinds, one resembling

that of Guadagnini, the other softer and richer in colour. The tone

may be described as large and very telling, and when the instrument

has had much use there is a richness by no means common. It is singular

that these instruments are more valued in Italy than they are either

in England or France. BALESTRIERI, Pietro,

Cremona, about 1725. BASSIANO, Rome. Lute-maker.

1666. BELLOSIO, Anselmo,

Venice, 18th century. About 1788. Similar to Santo Serafino in pattern,

but the workmanship is inferior; neat purfling; rather opaque varnish. BENTE, Matteo, Brescia,

latter part of the 16th century. M. F�tis mentions, in his "Biographie

Universelle des Musiciens," a Lute by this maker, richly ornamented. BERGONZI, Carlo,

Cremona, 1716-47. Pupil of Antonio Stradivari. That he was educated in Violin-making

by the greatest master of his art is evidenced beyond doubt. In

his instruments may be clearly traced the teachings of Stradivari.

The model, the thicknesses, and the scroll, together with the general

treatment, all agree in betokening that master's influence. Giuseppe

Guarneri del Ges� here stands in strong contrast with Bergonzi.

All writers on the subject of Violins assume that Guarneri was instructed

by Stradivari, a statement based upon no reasons (for none have

ever been adduced), and apparently a mere repetition of some one's

first guess or error. As before remarked, Carlo Bergonzi, in his

work, and in the way in which he carries out his ideas, satisfactorily

shows the source whence his early instructions were derived, and

may be said to have inscribed the name of his great master, not

in print, but in the entire body of every instrument which he made.

This cannot be said of Giuseppe Guarneri. On the contrary, there

is not a point throughout his work that can be said to bear any

resemblance to the sign manual of Stradivari. As this interesting

subject is considered at length in the notice of Giuseppe Guarneri,

it is unnecessary to make further comment in this place. The instruments of

Carlo Bergonzi are justly celebrated both for beauty of form and

tone, and are rapidly gaining the appreciation of artistes and amateurs.

Commercially, no instruments have risen more rapidly than those

of this maker; their value has continuously increased within recent

years, more particularly in England, where their merits were earliest

acknowledged—a fact which certainly reflects much credit upon

our connoisseurs. In France they had a good character years ago,

and have been gaining rapidly upon their old reputation, and now

our neighbours regard them with as much favour as we do. They possess tone

of rare quality, are for the most part extremely handsome, and,

last and most important of all, their massive construction has helped

them, by fair usage and age, to become instruments of the first

order. The model of Bergonzi's Violins is generally flat, and the

outline of his early efforts is of the Stradivari type; but later

in life, he, in common with other great Italian makers, marked out

a pattern for himself from which to construct. The essential difference

between these two forms lies in the angularity of the latter. It

would be very difficult to describe accurately the several points

of deviation unless the reader could handle the specimens for himself

and have ocular demonstration; the upper portion from the curve

of the centre bouts is increased, and, in consequence, the sound-holes

are placed slightly lower than in the Stradivari model. Bergonzi

was peculiar in this arrangement, and he seldom deviated from it.

Again, increased breadth is given to the lower portion of the instrument,

and in consequence the centre bouts are set at a greater angle than

is customary. The sound-hole may be described as an adaptation of

the characteristics of both Stradivari and Guarneri, inclining certainly

more to those of the former. As a further peculiarity, it is to

be noticed that the sound-holes are set nearer the edge than is

the case in the instruments of either of the makers named. Taken

as a whole, Bergonzi's design is rich in artistic feeling, and one

which he succeeded in treating with the utmost skill. Carlo Bergonzi furnishes

us with another example of the extensive research with which the

great Cremonese makers pursued their art, and a refutation of the

common assertion that these men worked and formed by accident rather

than by judgment. The differences of the two makers mentioned above,

as regards form, are certainly too wide to be explained away as

a mere accident. It is further necessary to take into consideration

the kind of tone belonging to these instruments respectively. If

Bergonzi's instruments be compared with those of his master, Stradivari,

or of Guarneri del Ges�, the appreciable difference to be found

will amount to this, that in Bergonzi's instruments there is a just

and exact combination of the qualities of both the other two makers

named. Is it not, therefore, reasonable to conclude that Carlo Bergonzi

was fully alive to the merits of both Stradivari and Guarneri, and

deliberately set himself to construct a model that should embrace

in a measure the chief characteristics of both of them? The scroll is deserving

of particular attention. It is quite in keeping with the body of

the instrument, and has been cut with a decision of purpose that

could only have been possessed by a master. It is flatter than usual,

if we trace it from the cheek towards the turn, and is strikingly

bold. Here, again, is the portrait of the character of the maker.

Although by a pupil of Antonio Stradivari, the scroll is thoroughly

distinct from any known production of that maker—it lacks

his fine finish and exact proportion; but, on the other hand, it

has an originality about it which is quite refreshing. The prominent

feature is the ear of the scroll, which being made to stand forth

in bold relief, gives it a broad appearance when looked at from

the front. The work of Bergonzi,

as has been the case with many of his class, has been attributed

to others. Many of his instruments are dubbed "Joseph Guarneri,"

a mistake in identification which arises chiefly from the form of

the sound-hole at the upper and lower portions. There is little

else that can be considered as bearing any resemblance whatever

to the work of Guarneri, and even in this case the resemblance is

very slight. Bergonzi's outline is totally different from that of

Guarneri, and is so distinct and telling that it is sure to impress

the eye of the experienced connoisseur when first seen. The varnish of Bergonzi

is often fully as resplendent as that of Giuseppe Guarneri or Stradivari,

and shows him to have been initiated in the mysteries of its manufacture.

It is sometimes seen to be extremely thick, at other times but sparingly

laid on; often of a deep, rich red colour, sometimes of a pale red,

and again, of rich amber, so that the variation of colour to be

met with in Bergonzi's Violins is considerable. We must concede

that his method of varnishing was scarcely so painstaking as that

of his fellow-workers, if we judge from the clots here and there,

particularly on the deep-coloured instruments; but, nevertheless,

now that age has toned down the varnish, the effect is good. Carlo Bergonzi lived

next door to Stradivari, and I believe the house remained in the

family until a few years since, when it was disposed of. Lancetti remarks:

"From want of information, we have forgotten in the second

volume"—referring to his "Biographical Dictionary,"

part of which was printed in 1820—"to include an estimable

maker named Carlo Bergonzi, who was pupil of Stradivari, and fellow-workman

with his sons. From the list of names and dates collected by Count

Cozio, it appears that Carlo Bergonzi worked by himself from 1719

to 1746. He used generally very fine foreign wood, and a varnish

the quality of that of his master." In the collection of Count

Cozio di Salabue, there were two Violins by Bergonzi, dated 1731

and 1733, and a Violoncello, 1746. We have in this country two remarkable

Violoncellos of this maker. The perfect and unique Double Bass which

Vuillaume purchased of the executors of Luigi

Tarisio is now in the possession of the family of the late Mr. J.

M. Sears, of Boston, U.S. BERGONZI, Michel

Angelo, Cremona, 1730-60. Son of Carlo. The pattern of his instruments

is somewhat varied. Many are large, and others under-sized. The

varnish is hard, and distinct from that associated with Cremonese

instruments.

BERGONZI, Niccol�,

Cremona. Son of the above. He made a great number of Violins of

similar form to those of his father. The wood which he selected

was of a close nature and hard appearance. The varnish is not equal

to that of Carlo; it is thin and cold-looking. The workmanship is

very good, being often highly finished, but yet wanting in character.

The scroll is cramped, and scarcely of the Cremonese type. Lancetti

mentions a Tenor by this maker, dated 1781. In the correspondence

which passed between the grandson of Antonio Stradivari and the

agents of Count Cozio (which is given in these pages), reference

is made to some of the moulds of the great maker being in the keeping

of —— Bergonzi, they having been lent to him, the writer

saying that he would obtain them and put them with the other patterns,

which appears to have been done. These moulds were doubtless lent

to Michel Angelo Bergonzi, and were used by Niccol� as well as his

father, which accounts for the form of their instruments being varied. BERGONZI, Zosimo,

Cremona. Brother of Niccol�. BERGONZI, Carlo,

Cremona, about 1780-1820. Son of Michel Angelo. He made a few Violins, large Stradivarius

form, sound-holes straight and inelegant. BERGONZI, Benedetto,

Cremona, died in 1840. Tarisio learned little points of interest

concerning Stradivari and his contemporaries from Benedetto Bergonzi. BERTASSI, Ambrogio,

Piadena (near Cremona), about 1730. BIANCHI, Niccol�,

Genoa and Nice. Worked until about 1875. BIMBI, Bartolommeo,

Siena, 1753-69. High-built, small pattern, orange-yellow varnish. BODIO, G. B., Venice,

about 1832. Good workmanship; oil varnish, wide purfling. BORELLI, Andrea,

Parma, about 1735. His instruments are little known; they resemble

those of Giuseppe Guadagnini. BRENSIO, Girolamo

(BRENSIUS, Hieronymus), Bologna. Reference has been made to the

Viols of this maker in the first section of this work. BRESCIA, Da, Battista.

A Pochette or Kit of this maker is at the Academy of Music, Bologna,

signed "Baptista Bressano"; the period assigned to it

is the end of the 15th century. BROSCHI, Carlo,

Parma. Carlo Broschi in

Parma, fecit 1732. BUSSETO, Giovanni

M., Cremona, 1540-80. Maker of Viols. M. F�tis mentions, in his

"Biographie des Musiciens," that Busseto derived his name

from Busseto, a borough in the Duchy of Parma, where

he was born. He also mentions a Viol of this maker, dated 1580,

which was found at Milan in 1792. CALCAGNI, Bernardo,

Genoa, about 1740. Neat workmanship, small scroll, flat model, well-cut

sound-holes, Stradivari pattern, orange-red varnish. CALVAROLA, Bartolommeo,

Bergamo, about 1753. The work is neatly executed. These instruments

are somewhat like those of Ruggeri in form. The scroll is weak,

and ill-proportioned. CAMILLI, Camillo,

Mantua, 17—. The form partakes of that of Stradivari; wood

usually of excellent quality. The sound-hole is rather wide and

short. The varnish resembles that of Landolfi, but is less brilliant. CAPPA, Gioffredo,

Cremona, 1644-1717. The dates of birth and death were ascertained

by Dr. Orazio Roggiero, a lawyer of Saluzzo, whose researches set

at rest many doubts and speculations as to this excellent maker

and his period of activity. He was formerly held to be a pupil of

the brothers Amati, but the assumption, having regard to the date

of birth, is untenable. The greater number

of his productions consist of works of high merit. Their likeness

to the instruments of the Amati is in some instances peculiarly

striking, but in others there is a marked dissimilarity. Particularly

is this the case in the form of the sound-hole and scroll. The sound-hole

is sometimes large, and quite out of keeping with the elegant outline

of Amati. The points of difference may be summed up as follows:

the sound-hole is larger, and more obliquely set in the instrument;

the upper portion of the body has a more contracted appearance;

the head, as is the case with most makers, differs most, and, in

this instance, in no way resembles Amati. There are few specimens

of Cappa that bear their original labels; most of them are counterfeit

"Amatis," and hence the great confusion which has arisen

concerning their parentage. Lancetti says: "Foreign professors

and amateurs, and particularly the English—though connoisseurs

of the good and the beautiful—in buying the instruments of

Cappa thought they had acquired those of Amati, the outline and

character of the varnish and the quality of the tone resembling

in some measure the instruments of the Brothers Amati. It is, however,

reserved to a few Italian connoisseurs to distinguish them. Those

of large pattern, and even of medium size, that have not been injured

by unskilful restorers, are scarce, and realise high prices."

These remarks, suggested many years since, by so able a connoisseur

as Count Cozio, possess a peculiar interest, and cannot fail to

interest the reader. As Lancetti remarks, they are of two patterns,

one larger than the other. The large one is, of course, the more

valuable; it is flatter, and altogether better finished. The Violoncellos

of Cappa are among the best of the second-class Italian instruments,

and are well worthy the attention of the professor and amateur.

The varnish is frequently of very rich quality, its colour resembling

that of Amati in many instances. CARCASSI, Francesco,

Florence, about 1758. CARCASSI, Lorenzo,

about 1738. CARCASSI, Tomaso,

worked in partnership with Lorenzo, but also alone, according to

labels. There were several makers of this name. CASINI, Antonio,

Modena. Antonius Casini,

fecit Mutine anno 1680. CASTAGNERI, Andrea,

Paris, about 1735. This Italian maker appears to have settled in

Paris. I have seen a Violin by Castagneri, date 1735; flat model,

bold outline, and varnish of good quality. CASTELLANI, Pietro,

Florence, died about 1820. CASTELLANI, Luigi,

Florence, died 1884. CASTRO, Venice, 1680-1720.

The wood is of good figure generally. The outline is defective;

the middle bouts are too long to be proportionate. Sound-hole roughly

worked. Varnish red, the quality of which is scarcely up to the

Venetian standard. CATENAR, Enrico,

Turin, about 1671. Henricus Catenar,

fecit Taurini anno 167— CELIONIATI, Gian

Francesco, Turin, about 1734. Appears to have copied the form of

Amati. Yellow varnish, good workmanship. CERIN, Marco Antonio,

Venice, end of the eighteenth century. Signed himself as a pupil

of Belosio. Marcus Antonius

Cerin, alumnus Anselmi Belosii, fecit Veneti�, 17— CERUTI, Giovanni

Battista, Cremona, 1755-1817. Ceruti made a large number of Violins

and Violoncellos of the Pattern of Amati. He appears to have been

a prolific workman, his instruments numbering, it is said, about

five hundred. His favourite model was the large Amati. Giovanni

Ceruti succeeded to the business of Lorenzo Storioni in 1790, in

the Via dei Coltellai, near the Piazza St. Domenico. CERUTI, Giuseppe,

son of Giovanni, Cremona, 1787-1860. Was a maker and restorer of

instruments. He is said to have exhibited, at the Paris and other

exhibitions, Violins of good quality. He died at Mantua, in 1860. CERUTI, Enrico, son

of Giuseppe, Cremona, born in 1808, died on October 30, 1883. Enrico

Ceruti is the last of the long line of Cremonese Violin-makers;

there is, in consequence, a peculiar interest attached to him. Independent

of this, however, he is deserving of special notice from his having

been the recipient of the traditional history attending the makers

of Cremona, from Amati to Stradivari and Bergonzi, and from Bergonzi

to Storioni and Ceruti. He was acquainted with Luigi Tarisio and

with Vuillaume, to whom he gave many interesting particulars relative

to the great makers of his native city. The instruments of Enrico

Ceruti are much valued by Italian orchestral players. They are said

to number about three hundred and sixty-five, among which are several

Violoncellos. He exhibited at the London Exhibition of 1862, and

at other exhibitions. The last Violin he made was shown at the Milan

Exhibition, 1881. CRISTOFORI, Bartolommeo,

Padua and Florence, 1667-1731. Apprenticed to Niccol� Amati. Is

best known as the inventor of the "hammer system," and,

therefore, the father of the modern pianoforte. Bow instruments

of his make are rare, but authentic examples are in every way excellent.

A fine Double Bass, dated 1715, is in the museum of the Musical

Academy in Florence. Violoncellos and other instruments are known,

and it is to be regretted that so few specimens are to be met with. CIRCAPA, Tommaso,

Naples, about 1730. COCCO, Cristoforo,

Venice, 1654. A Lute-maker. The Museum of the Paris Conservatoire Nationale

de Musique contains a specimen of this make, which is described

in M. Gustave Chouquet's catalogue of the collection. CONTRERAS, Joseph,

Madrid, 1745-80. This being one of the few Spanish makers, his name

is placed with the Italian, the number of the Spanish being insufficient

for a separate list. The model of this maker is very good and the

workmanship superior. He probably lived In Italy during his early

life, the style being Italian. He was born in Granada, and was called

the Spanish Stradivarius. He died about 1780, and is said to have

been seventy years of age. CORDANO, Jacopo

Filippo, Genoa, about 1774. Jacobus Philipus

Cordanus, fecit Genu� anno sal. 1774. CORNA, Dalla, Brescia,

early maker of Viols, about 1530. COSTA, Pietro Antonio

dalla, Venice and Treviso. The label he used is curious.

He copied the Brothers Amati with much skilfulness. The sound-holes

are like those of the early instruments of the Amati; the varnish

is golden in colour and excellent in quality; the scroll, as usual

with all imitations, is a weak feature, but does not lack originality. DARDELLI, Pietro,

Mantua, about 1500. Is described as a maker of Lutes and Viols.

M. F�tis relates, in his "Biographie des Musiciens," that

the painter Richard, of Lyons, possessed about the year 1807 a beautiful

Lute by this maker, which was made for the Duchess of Mantua. The

instrument is described as richly inlaid with ebony, ivory, and

silver, dated 1497, and having the name "Padre Dardelli."

On the belly the Mantuan arms are represented. M. F�tis was unable

to discover any tidings of this interesting instrument after the

death of Richard. Dardelli was a Franciscan monk at Mantua, and

occupied himself with making musical instruments and inlaying them.

Work of any kind executed under such circumstances is rarely found

to be other than artistic. DESPINE, Alexander,

Turin, nineteenth century. A very good maker; worked with Pressenda,

whose labels his instruments sometimes bear. DIEFFOPRUCHAR, Magno,

Venice, 1612. Lute-maker. An instrument of this make is at the Academy

of Music, Bologna. M. Engel remarks, "There can be no doubt

that we have here the Italianised name of the German Magnus Tieffenbrucker,

who lived in Italy." There appears to be a connection between

these Venetian Lute-makers of this name and Duiffoprugcar of the

sixteenth century. DOMINICELLI, Ferrara,

said to have worked about 1700. DUIFFOPRUGCAR, Gaspar,

Bologna. This famous maker of Viols is said to have settled in Bologna

in the early part of the sixteenth century. He appears to have obtained

much renown as an inlayer of musical instruments, and it is stated

that Francis I., upon the occasion of his visit to Italy in 1515,

prevailed upon the Viol-maker to settle in France. The name of Duiffoprugcar

has been made familiar to us, not so much on account of his merits

as a Viol-maker, but almost wholly on account of his having been

represented as the first maker of the Violin tuned in fifths, and

the representation having been supported by the production of three

Violins signed and dated 1511, 1517, 1519. I saw, about the year

1877, one of these, and was informed by the owner that the others

were almost identical. The instrument bore distinct evidence of

its being a modern French imitation, or rather an ingenious creation

evolved from a myth, which in all probability had its origin in

France. Duiffoprugcar was unquestionably an artist of a high order,

but his abilities appear to have been chiefly directed to the art

of wood-inlaying, rather than to the making of stringed instruments.

He made Viols da Gamba, and he may have made smaller Viols, though

I am not aware of any being in existence; but there is no evidence

whatever to show that he made Violins. FARINATO, Paolo,

Venice, 1695-1725. FICKER, Johann Christian,

Cremona, middle of the 18th century. Although dating from Cremona,

has nothing in common with Cremonese work. FICKER, Johann Gottlieb,

Cremona, 1788. FIORILLO, Giovanni,

Ferrara, 1780. The style is a mixture of German and Italian, the former

preponderating. The sound-hole is an imitation of that of Stainer.

His Violoncellos are among his best instruments. FIORINO, Fiorenzi,

Bologna, about 1685. FREI, Hans, Bologna,

1597. Lute and Viol-maker. There is an instrument of this make at

the Bologna Academy of Music. It is probable there was a family

connection between Hans Frey, of Nuremberg, and this maker. GABRIELLI, Giovanni

Battista, Florence, about the middle of the 18th century. The instruments