|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

SECTION II The Construction of the Violin The construction

of the present form of the Violin

has occupied the attention of many scientific men. It cannot be

denied that the subject possesses a charm sufficiently powerful

to induce research, as endeavour is made to discover the causes

for the vast superiority of the Violin of the seventeenth century

over the many other forms of bow instruments which it has survived.

The characteristic differences of the Violin have been obtained

at the cost of many experiments in changing the outline and placing

the sound-holes in various incongruous positions. These, and the

many similar freaks of inventors in their search after perfection,

have signally failed, a result to be expected when it is considered

that the changes mentioned were unmeaning, and had nothing but novelty

to recommend them. But what is far more extraordinary is the failure

of the copyist, who, vainly supposing that he has truthfully followed

the dimensions and general features of the Old Masters, at last

discovers that he is quite unable to construct an instrument in

any way deserving of comparison with the works of the period referred

to. The Violin has thus hitherto baffled all attempts to force it

into the "march of progress" which most things are destined

to follow. It seems to scorn complication in its structure, and

successfully holds its own in its simplicity. There is in the Violin,

as perfected by the great Cremonese masters, a simplicity combined

with elegance of design, which readily courts the attention of thoughtful

minds, and gives to it an air of mystery that cannot be explained

to those outside the Fiddle world. Few objects possess so charming

a display of curved lines as the members of the Violin family. Here

we have Hogarth's famous line of beauty worked to perfection in

the upper bouts, in the lower bouts, in the outer line of the scroll,

in the sound-hole. Everywhere the perfection of the graceful curve

is to be seen. It has been asserted by Hogarth's enemies that he

borrowed the famous line from an Italian writer named Lomazzo, who

introduced it in a treatise on the Fine Arts. We will be more charitable,

and say that he obtained it from the contemplation of the beauties

of a Cremonese Violin. In looking at a Violin

we are struck with admiration at a sight of consummate order and

grace; but it is the grace of nature rather than of mechanical art.

The flow of curved lines which the eye detects upon its varied surface,

one leading to another, and all duly proportioned to the whole figure,

may remind us of the winding of a gentle stream, or the twine of

tendrils in the trellised vine. Often is the question

asked, What can there be in a simple Violin to attract so much notice?

What is it that causes men to treat this instrument as no other,

to view it as an art picture, to dilate upon its form, colour, and

date? To the uninitiated such devotion appears to be a species of

monomania, and attributable to a desire of singularity. It needs

but little to show the inaccuracy of such hypotheses. In the first

place, the true study of the Violin is a taste which needs as much

cultivation as a taste for poetry or any other art, a due appreciation

of which is impossible without such cultivation. Secondly, it needs,

equally with these arts, in order to produce proficiency, that spark

commonly known as genius, without which, cultivation,

strictly speaking, is impossible, there being nothing to cultivate.

We find that the most ardent admiration for the Violin regarded

as a work of art, has ever been found to emanate from those who

possessed tastes for kindred arts. Painters, musicians, and men

of refined minds have generally been foremost among the admirers

of the Violin. Much interest attaches to it from the fact of its

being the sole instrument incapable of improvement, whether in form

or in any other material feature. The only difference between the

Violin of the sixteenth century and that of the nineteenth lies

in the arrangement of the sound-bar (which is now longer, in order

to bear the increased pressure caused by the diapason being higher

than in former times), and the comparatively longer neck, so ordered

to obtain increased length of string. These variations can scarcely

be regarded as inventions, but simply as arrangements. The object

of them was the need of adapting the instrument to modern requirements,

so that it might be used in concert with others that have been improved,

and allow the diapason to be raised. Lastly, it must be said that,

above all, the Violin awakens the interest of its admirers by the

tones which it can be made to utter in the hands of a skilful performer.

It is, without doubt, marvellous that such sounds should be derivable

from so small and simple-looking an instrument. Its expressiveness,

power, and the extraordinary combinations which its stringing admits

of, truly constitute it the king of musical instruments. These somewhat

desultory remarks may suffice to trace the origin of the value set

upon the Violin both as a work of art and as a musical instrument. We will now proceed

to consider the acoustical properties of the Violin. These are,

in every particular, surprisingly great, and are the results of

many tests, the chief of which has been the adoption of several

varieties of wood in its construction. In Brescia, which was in

all probability the cradle of Violin manufacture, the selection

of the material of the sides and back from the pear, lemon, and

ash trees was very general, and there is every reason to believe

that Brescia was the first place where such woods were used. It

is possible that the makers who chose them for the sides and backs

of their instruments considered it desirable to have material more

akin to that adopted for the bellies, which was the finest description

of pine, and that the result was found to be a tone of great mellowness.

If they used these woods with this intention, their calculations

were undoubtedly correct. They appear to have worked these woods

with but few exceptions for their Tenors, Violoncellos, and Double

Basses, while they adopted the harder woods for their Violins, all

which facts tend to show that these rare old makers did not consider

soft wood eligible for the back and sides of the leading instrument;

and later experiment has shown them to have arrived at a correct

conclusion on this point. The experiments necessary to obtain these

results have been effected by cutting woods of several kinds and

qualities into various sizes, so as to give the sounds of the diatonic

scale. By comparing the intensity and quality of tone produced by

each sample of wood, plane-tree and sycamore have been found to

surpass the rest. The Cremonese makers seem to have adhered chiefly

to the use of maple, varying the manner of cutting it. First, they

made the back in one piece, technically known as a "whole back";

secondly, the back in two parts; thirdly, the cutting known as the

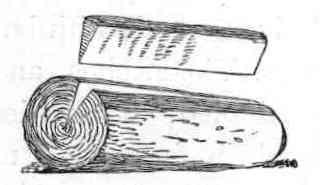

"slab back." There being considerable doubt as to the

mode of dividing the timber, the woodcuts given will assist the

reader to understand it. Fig. 1 represents the cutting for the back

in two pieces—the piece which is separated from the log is

divided. Fig. 2 shows the method adopted to obtain the slab form.

This mode of cutting

is constantly met with in the works of the Brescian makers, and

likewise in those of the early Cremonese. Andrea Amati invariably

adopted this form. Stradivari rarely cut his wood slab-form. Joseph

Guarneri made a few Violins of his best epoch with this cutting,

the varnish on which is of an exquisite orange colour, so transparent

that the curls of the wood beneath resemble richly illuminated clouds. There can be no doubt

whatever that the Cremonese and Brescian makers were exceedingly

choice in the selection of their material, and their discrimination

in this particular does not appear to have risen so much from a

regard to the beauty as to the acoustic properties of the wood,

to which they very properly gave the first place in their consideration.

We have evidence of much weight upon this interesting question in

the frequent piecings found on the works of Cremona makers, pointing

to a seeming preference on their part to retain a piece of wood

of known acoustic properties rather than to work in a larger or

better preserved portion at the probable expense of tone. The time

and care required for such a delicate operation must have been sufficient

to have enabled the maker, had he been so minded, to have made a

complete instrument. There is also ample proof that Joseph Guarneri

possessed wood to the exceptional qualities of which he was fully

alive, and the same may be said of Stradivari, Ruggeri, and others.

It is scarcely reasonable to suppose that in the seventeenth century

there was a dearth in Italy of timber suitable for the manufacture

of Violins, and that in consequence these eminent makers were compelled

to patch and join their material to suit their purpose. They were

men who were in the enjoyment of a patronage certainly sufficient

to enable them to follow their calling without privation of any

kind. Scarcity of pine and sycamore, good or bad, could not have

been the cause, since we find Italian cabinet-work of great beauty

that was manufactured at this same period. The plane-tree and pine

used by the Amati, Stradivari, and the chief masters in Italy, was

usually of foreign growth, and was taken from the Tyrol and Istria.

Its value was, therefore, in advance of Italian wood, but hardly

so much as to place it beyond the reach of the Cremonese masters.

It is, further, improbable that these masters of the art should

have expended such marvellous care and toil over their work, pieced

as it frequently was like mosaic, when for a trifling sum they could

have avoided such a task to their ingenuity by purchasing fresh

wood. We are therefore forced to admit that there must have been

some cause of great weight which induced them to apply so much time

and labour, and that the problem can only be accounted for by the

solution before proposed, viz., that external appearance was of

less importance than the possession of acoustic properties thoroughly

adapted to the old makers' purpose, and that the scarcity of suitable

wood was such as to make them hoard and make use of every particle.

The selection of material was hence considered to be of prime importance

by these makers; and by careful study they brought it to a state

of great perfection. The knowledge they gained of this vital branch

of their art is enveloped in a similar obscurity to that which conceals

their famous varnish, and in these branches of Violin manufacture

rests the secret of the Italian success, and until it is rediscovered

the Cremonese will remain unequalled in the manufacture of Violins. We may now pass to

the consideration of the various constituent parts of a Violin.

It will be found, if a Violin be taken to pieces, that it is constructed

of no less than fifty-eight separate parts, an astonishing number

of factors for so small and simple-looking an instrument. The back

is made of maple or sycamore, in one or two parts; the belly of

the finest quality of Swiss pine, and from a piece usually divided;

the sides, like the back, of maple, in six pieces, bent to the required

form by means of a heated iron; the linings, which are used to secure

the back and belly to the sides, are twelve in number, sometimes

made of lime-tree, but also of pine. The bass or sound-bar is of

pine, placed under the left foot of the bridge in a slightly oblique

position, in order to facilitate the vibrating by giving about the

same position as the line of the strings. The divergence is usually

one-twelfth of an inch, throughout its entire length of ten inches.

It is curious to discover that this system of placing the bar was

adopted by Brensius of Bologna, a Viol-maker of the fifteenth century,

and by Gasparo da Sal�. The later Violin-makers, however, for the

most part, do not appear to have followed the example, they having

placed it in a straight line, thus leaving the system to be re-discovered.

The bar of the Violin not only serves the purpose of strengthening

the instrument in that part where the pressure of the bridge is

greatest, but forms a portion of the structure at once curious and

deeply interesting; it may indeed be called the nervous system of

the Violin, so exquisitely sensitive is it to external touch. The

slightest alteration in its position will effect such changes in

the tone as often to make a good Violin worthless. Those troublesome

notes technically known as "wolf notes" by its delicate

adjustment are sometimes removed, or passed to intervals where the

disagreeable sound is felt with less intensity. Numerous attempts

have been made to reduce these features to a philosophy, but the

realisation of the coveted discovery appears as distant as ever.

The most minute variation in the construction of the instrument

necessitates a different treatment of this active agent as regards

its conjunction with the bridge; and when it is considered that

scarcely two Violins can be found of exactly identical structure,

it must be admitted that the difficulties in the way of laying down

any set of hard and fast rules for their regulation seem to be insuperable. The next important

feature of the internal organism is the sound-post, which serves

many purposes. It is the medium by which the vibratory powers of

the instrument are set in motion; it gives support to the right

side of the belly, it transmits vibrations, and regulates both the

power and quality of tone. The terms used for this vital factor

of a Violin on the Continent at once prove its importance. The Italians

and French call it the "Soul," and the Germans the "Voice."

If we accept the bass-bar as the nervous system of a Violin, the

sound-post may be said to perform the functions of the heart with

unerring regularity. The pulsations of sound are regulated by this

admirable contrivance. If mellowness of quality be sought, a slight

alteration of its position or form will produce a favourable change

of singular extent; if intensity of tone be requisite, the sound-post

is again the regulator. It must, of course, be understood that its

power of changing the quality of the tone is limited in proportion

to the constitutional powers of the instrument in each case. It

is not pretended that a badly constructed instrument can be made

a good one by means of this subtle regulator, any more than a naturally

weak person can be made robust by diet and hygiene. The position of the

sound-post is usually one-eighth to three-eighths of an inch behind

the right foot of the bridge, the distance being variable according

to the model of the instrument. If the Violin be high-built, the

post requires to be nearer the bridge, that its action may be stronger;

whilst flat-modelled instruments require that the post be set further

away from the bridge. It is not possible to have any uniform arrangement

of the sound-post in all instruments; as we have remarked before

in reference to the bass-bar, the variations in the thickness, outline,

model, &c., of the Violin are so frequent as to defy identity

of treatment; uniformity has been sought for, but without success. The post can only

be adjusted by a skilful workman, who either plays himself or has

the advantage of having the various adjustments tested by a performer.

The necessity of leaving this exceedingly delicate matter in practised

hands cannot be too strongly impressed upon the amateur, for the

damage done in consequence of want of skill is often irreparable. There are two methods

of setting the sound-post in the instrument: the first fixes it

in such a position as to place the grain of the post parallel with

the grain of the belly; the second sets it crosswise. The next important

feature to be mentioned is the bridge, which forms no small part

of the vibrating mechanism of the instrument, and needs the utmost

skill in its arrangement. Its usual position is exactly between

the two small niches marked in each sound-hole, but this arrangement

is sometimes altered in the case of the stop being longer or shorter.

Many forms of bridges have been in use at different periods, but

that now adopted is, without doubt, the best. In selecting a bridge

great care is requisite that the wood be suitable to the constitution

of the Violin. If the instrument is wanting in brilliancy, a bridge

having solidity of fibre is necessary; if wanting in mellowness,

one possessing soft qualities should be selected. We now pass to the

neck of the Violin, which is made of sycamore or plane-tree. Its

length has been increased since the days of the great Italian masters,

who seem to have paid but little attention to this portion of the

instrument, in regard to its appearance and as to the wood used

for its manufacture, which was of the plainest description. It may

be observed that in those times the florid passages which we now

hear in Violin music were in their infancy, the first and second

positions being those chiefly used; hence the little attention paid

to the handle of the instrument. Modern requirements have made it

imperative that the neck should be well shaped, neither too flat

nor too round, but of a happy medium. The difficulties of execution

are sensibly lessened when due attention is paid to this requirement. The finger-board

is of ebony, and varies a little in length according to the position

of the sound-holes. To form the board properly is a delicate operation,

for if it be not carefully made the strings jar against it, and

the movements of the bow are impeded. The nut, or rest, is that

small piece of ebony over which the strings pass on the finger-board. The purfling is composed

of three strips of lime-tree, two of which are stained black. Whalebone

purfling has been frequently used, particularly by the old Amsterdam

makers. The principal parts

of the instrument have now been described, and there remain only

the pegs, blocks, strings, and tail-piece, the sum of which makes

up the number of fifty-eight constituent parts as before mentioned.

There is still, however, one item of the construction to be mentioned

which does not form a separate portion of the Violin, but which

is certainly worthy of notice, viz., the button, which is that small

piece of wood against which the heel of the neck rests. The difficulty

of making this apparently insignificant piece can only be understood

by those who have gone through the various stages of Violin manufacture.

The amount of finish given to the button affects in a great measure

the whole instrument, and if there is any defect of style it is

sure to be apparent here. It is a prominent feature, and the eye

naturally rests upon it: as the key-stone to the arch, so is the

button to the Violin. The sound-holes,

or f-holes, it is almost needless to remark, are features

of vital importance. Upon the form given to them, and the manner

of cutting them, largely depend the volume and quality of tone.

The Italian makers of Brescia and Cremona appear to have been aware

of the singular influence the formation of the sound-hole has upon

the production and quality of sound. The variety of original shapes

they gave to them is evidence of their knowledge. Appearance in

keeping with the outline of their design may have influenced them

in some measure, but not entirely. Most makers used patterns from

which to cut their sound-holes; Joseph Guarneri and some others

appear to have drawn them on the belly, and cut them accordingly. From the foregoing

remarks upon the various portions of the Violin it may be assumed

that the reader has gained sufficient insight into the process of

its manufacture to enable him to dispense with a more minute description

of each stage. In conclusion, I

cannot refrain from cautioning possessors of good instruments against

entrusting them into the barbaric hands of pretended repairers,

who endeavour to persuade them into the belief that it is necessary

to do this, that, and the other for their benefit. The quack doctors

of the Violin are legion—they are found in every town and

city, ready to prey upon the credulity of the lovers of Fiddles,

and the injury they inflict on their helpless patients is frequently

irreparable. Unfortunately, amateurs are often prone to be continually

unsettling their instruments by trying different bars, sound-posts,

&c., without considering the danger they run of damaging their

property instead of improving it. Should your instrument need any

alteration, no matter how slight, consult only those who have made

the subject a special study. There are a few such men to be found

in the chief cities of Europe, men whose love for the instrument

is of such a nature that it would not permit them to recommend alterations

prejudicial to its well-being. Italian and other Strings Upon the strings

of the Violin depends in a great measure the successful regulation

of the instrument. If, after the careful adjustment of bridge, sound-post,

and bass-bar, strings are added which have not been selected with

due care and regard to their relative proportion, the labour expended

upon the important parts named is at once rendered useless. Frequently

the strings are the objects least considered when the regulation

of a Violin is attempted; but if this be the case, results anything

but satisfactory ensue. It is, therefore, important that every Violinist

should endeavour to make himself acquainted with the different varieties

and powers of strings, that he may arrange his instrument with due

facility. The remarkable conservatism

attending the structural formation of the Violin exists more or

less in the appliances necessary for the awakening of its dormant

music. If we turn to its pegs, we find them of the same character

as the peg of its far-removed ancestor, the monochord; and if we

compare the Italian peg of the seventeenth century with a modern

one, the chief difference lies in the latter being more gross and

ugly. Upon turning to the bridge, we see that the bridge of today

is almost identical with the bridge of Stradivari; and when we come

to the strings of the Violin, we discover that we have added but

little, if anything, to the store of information regarding them

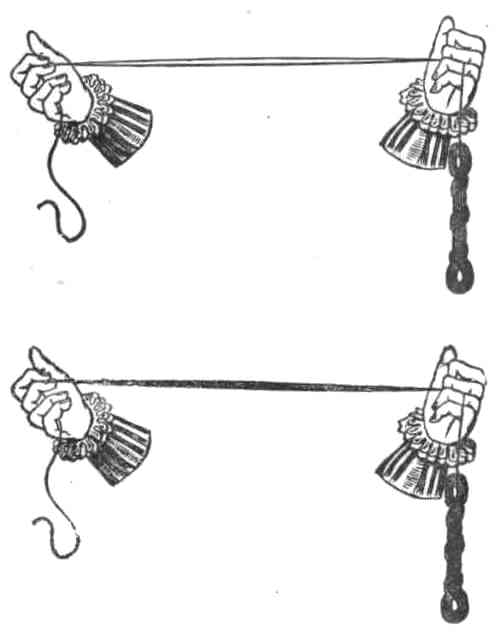

possessed by our forefathers. In, perhaps, the

earliest book on the Lute, that of Adrian Le Roy, published in Paris

in 1570, and translated into English in 1574, we read: "I will

not omit to give you to understand how to know strings." "It

is needful to prove them between the hands in the manner set forth

in the figures hereafter pictured, which show on the finger and

to the eye the difference from the true with the false." The

instructions here given, it will be seen, are those set forth by

Louis Spohr in his "Violin School." In the famous musical

work of Merseene, published in 1648, we find an interesting account

of strings; he says they are of "metal, and the intestines

of sheep." "The thicker chords of the great Viols and

of Lutes are made of thirty or forty single intestines, and the

best are made in Rome and some other cities in Italy. This superiority

is owing to the air, the water, or the herbage on which the sheep

of Italy feed." He adds that "chords may be made of silk,

flax, or other material," but that "animal chords are

far the best." The experience of upwards of two centuries has

not shaken the soundness of Merseene's opinion of the superiority

of gut strings over those made of silk and steel. Although strings

of steel and silk are made to some extent on account of their durability

and their fitness for warm climates, no Violinist familiar with

the true quality of tone belonging to his instrument is likely to

torture his ears with the sound of strings made with thread or iron.

Continuing our inquiries among the old musical writers in reference

to the subject of strings, we find Doni says in his musical treatise,

published in 1647: "There are many particulars relating to

the construction of instruments which are unknown to modern artificers,

as, namely, that the best strings are made when the north and the

worst when the south wind blows," a truism well understood

by experienced string manufacturers. Thomas Mace, in his curious

book on the Lute, enters at some length into the question of strings,

and speaks in glowing terms of his Venetian Catlins.

The above references to strings, met with in the writers of the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, indicate a full knowledge of

the most important facts concerning them on the part of the musicians

and makers of those days; and notwithstanding our superior mechanical

contrivances in the manufacture, it is doubtful whether modern strings

are generally equal to those made in times when leisure waited on

quality, in lieu of speed on quantity.

Musical strings are

manufactured in Italy, Germany, France, and England. The Italians

rank first, as in past times, in this manufacture, their proficiency

being evident in the three chief requisites for string, viz., high

finish, great durability, and purity of sound. There are manufactories

at Rome, Naples, Padua, and Verona, the separate characteristics

of which are definitely marked in their produce. Those strings which

are manufactured at Rome are exceedingly hard and brilliant, and

exhibit a slight roughness of finish. The Neapolitan samples are

smoother and softer than the Roman, and also whiter in appearance.

Those of Padua are highly polished and durable, but frequently false.

The Veronese strings are softer than the Paduan, and deeper in colour.

The variations described are distinct, and the more remarkable that

all the four kinds are produced by one and the same nation; as,

however, the raw material is identical throughout Italy, the process

of manufacture must be looked upon as the real cause of the difference

noticed. The German strings now rank next to the Italian, Saxony

being the seat of manufacture. They may be described as very white

and smooth, the better kinds being very durable. Their chief fault

arises from their being over-bleached, and hence faulty in sound.

The French take the third place in the manufacture. Their strings

are carefully made, and those of the larger sizes answer well; but

the smaller strings are wanting in durability. The English manufacture

all qualities, but chiefly the cheaper kinds; they are durable,

but unevenly made, and have a dark appearance. The cause of variation

in quality of the several kinds enumerated arises simply from the

difference of climate. In Italy an important part of the manufacture

is carried on in the open air, and the beautiful climate is made

to effect that which has to be done artificially in other countries.

Hence the Italian superiority. Southern Germany adopts, to some

extent, similar means in making strings; France, to a less degree;

while England is obliged to rely solely on artificial processes.

It therefore amounts to this—the further from Italy the seat

of manufacture, the more inferior the string. From the foregoing

references we find that strings, although called "catgut,"

are not made from the intestines of that domestic animal. Whether

they were originally so made, and hence derive their name, it is

impossible to learn. Marston, the old dramatist, says:

We may be sure, however,

that had the raw material been drawn from that source up to the

present time, there would have been no need to check the supply

of the feline race by destroying nine kittens out of ten; on the

contrary, the rearing of cats would indeed have been a lucrative

occupation. A time-honoured error is thus commemorated in a word,

the origin of which must be ascribed to want of thought. If the

number of cats requisite for the string manufacture be considered

for a moment, it is easy to see that Shylock's "harmless necessary"

domestics are under no contribution in this matter. Strings are

made from the intestines of the sheep and goat, chiefly of the former.

The best qualities are made from the intestines of the lamb, the

strength of which is very great if compared with those of a sheep

more than a year old. This being so, the chief manufacture of the

year is carried on in the month of September, the September string-makings

being analogous to October brewings. The demand for strings made

at this particular season far exceeds the supply, and notably is

this the case with regard to strings of small size, which have to

bear so great a strain that if they were not made of the best material

there would be little chance of their endurance. To enter into a

description of the various processes of the manufacture is unnecessary,

as it would form a subject of little interest to the general reader;

we may therefore conclude this brief notice of strings by a few

rules to be observed in their selection. Endeavour to obtain

strings of uniform thickness throughout, a requisite which can only

be insured by careful gauging. In selecting the E string, choose

those that are most transparent; the seconds and thirds, as they

are made with several threads, are seldom very clear. The firsts

never have more than a few threads in them, and hence, absence of

transparency in their case denotes inferior material. Before putting

on the first string, in particular, in order to test its purity

it will be well to follow Le Roy's advice, which is to hold between

the fingers of each hand a portion of the string sufficient to stretch

from the bridge to the nut, and to set it in vibration. If two lines

only be apparent, the string is free from falseness; but if a third

line be produced, the contrary conclusion must be assumed. In the

case of seconds and thirds we cannot always rely on this test, as

the number of threads used in their manufacture frequently prevents

the line from being perfectly clear. The last precaution of moment

is to secure perfect fifths, which can only be done by taking care

that the four strings are in true proportion and uniform with each

other. To string a violin correctly is a very difficult undertaking,

and requires considerable patience. The first consideration should

be the constitution of the Violin: the strings that please one instrument

torture another. Neither Cremonese Violins nor old instruments in

general require to be heavily strung: the mellowness of the wood

and their delicate construction require the stringing to be such

as will assist in bringing out that richness of tone which belongs

to first-rate instruments. If the bridge and sound-board be heavily

weighted with thick strings, vibration will surely be checked. In

the case of modern instruments, heavy in wood, and needing constant

use to wear down their freshness, strings of a larger size may be

used with advantage, and particularly when such instruments are

in use for orchestral purposes.

Vast improvements

have been effected in the stringing of Violins within the last thirty

years. Strings of immense size were used alike on Violins, Violoncellos,

Tenors, and Double Basses. Robert Lindley, the king of English Violoncellists,

used a string for his first very nearly equal in size to the second

of the present time, and the same robust proportion was observed

in his other strings. The Violoncello upon which he played was by

Forster, and would bear much heavier stringing than an Italian instrument;

and, again, he was a most forcible player, and his power of fingering

quite exceptional. Dragonetti, the famous Double-Bass player, and

coadjutor of Lindley, possessed similar powers, and used similar

strings as regards size. Their system of stringing was adopted indiscriminately.

Instruments whether weakly or strongly built received uniform treatment,

the result being in many cases an entire collapse, and the most

disappointing effects in tone. It was vainly supposed that the ponderous

strings of Dragonetti and Lindley were the talisman by use of which

their tone would follow as a matter of course, whereas in point

of fact it was scarcely possible to make the instruments utter a

sound when deprived of the singular muscular power possessed by

those famous players. After Lindley's death his system passed away

gradually, and attention was directed to the better adaptation of

strings to the instrument, and also to the production of perfect

fifths. We have now only

to speak of covered strings, in which it is more difficult to obtain

perfection than in the case of those of gut. There are several kinds

of covered strings. There are those of silver wire, which are very

durable, and have a soft quality of sound very suitable to old instruments,

and are therefore much used by artistes; there are those of copper

plated with silver, and also of copper without plating, which have

a powerful sound; and, lastly, there are those which are made with

mixed wire, an arrangement which prevents in a measure the tendency

to rise in pitch, a disadvantage common to covered strings and caused

by expansion of the metals; these strings also possess a tone which

is a combination of that produced by silver and copper strings.

Here again, however, great discrimination is needed, viz., before

putting on the fourth string. The instrument must be understood.

There are Violins which will take none but fourths of copper, there

are others that would be simply crippled by their adoption. It cannot

be too much impressed upon the mind of the player that the Violin

requires deep and patient study with regard to every point connected

with its regulation. So varied are these instruments in construction

and constitution, that before their powers can be successfully developed

they must be humoured, and treated as the child of a skilful educator,

who watches to gain an insight into the character of his charge,

and then adopts the best means for its advancement according to

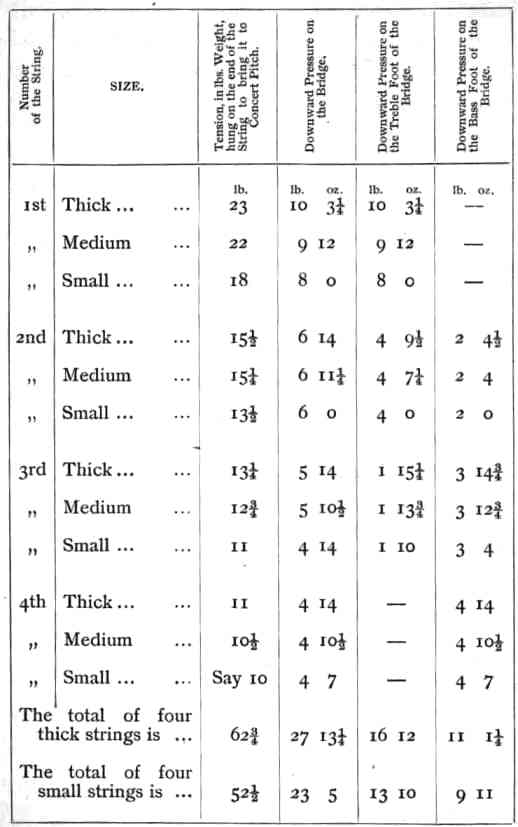

the circumstances ascertained. The strain and pressure

of the strings upon a Violin being an interesting subject of inquiry,

I give the annexed particulars (see Table below) from

experiments made in conjunction with a friend interested in the

subject, and possessed of the necessary knowledge to arrive at accurate

results. The Violin being

held in a frame in a nearly upright position, so that the string

hung just clear of the nut to avoid friction, the note was obtained

by pressing the string to the nut. When the Violin was

laid in a horizontal position, and the string passed over a small

pulley, an additional weight of two or three pounds was required

to overcome the friction on the nut and that of the pulley. Therefore

it is probable that the difference in the results obtained by other

experiments may have arisen from the different methods employed.

But with a dead weight hung on the end of each string there could

be no error. TENSION OF VIOLIN STRINGS.

B A C is the average

angle formed by a string passing over the bridge of a Violin, and

the tension acts equally in the direction A B, A C.

Take A C=A B. From the point B

draw B D parallel to A C. And from the point C draw C D parallel

to A B, cutting B D at D. Join A D. Then, if a force

acting on the point A, in the direction of A B, be represented in

magnitude by the line A B, an equal force acting in the direction

A C will be represented by the line A C, and the diagonal A D will

represent the direction and magnitude of the force acting on the

point A, to keep it at rest. N.B.—The bridge

of a Violin does not divide the angle B A C quite equally, but so

nearly that A D may be taken as the position of the bridge. Also, the plane passing

through the string of a Violin, on both sides of the bridge, is

not quite perpendicular to the belly. To introduce this variation

into the calculation would render that less simple, and it will

be sufficient to state that about the 150th part must be deducted

from the downward pressures given in the above table from the first

and fourth strings, and about the 300th part for the second and

third strings. The total to be deducted for the four strings will

not exceed three ounces. On the line A B or

A C set off a scale of equal parts, beginning at A, and on A D a

similar scale beginning at A. Mark off on the scale

A B as many divisions as there are lbs. in the tension of a string,

for example 18, and from that point draw a line parallel to B D,

cutting A D at the point 8 in that scale. Then, if the tension of

a string be 18 lb., the downward pressure on the bridge will be

8 lb.; and therefore for the above angle the downward pressure of

any string on the bridge will be 8/18=4/9 of the tension of that

string. The whole of the

downward pressure of the first string falls upon the Treble Foot

of the Bridge. The downward pressure

of the second string is about 2/3 the Treble Foot of the Bridge,

and 1/3 on the Bass Foot. The downward pressure

of the third string is about 1/3 on the Treble Foot, and 2/3 on

the Bass Foot. The whole of the

downward pressure of the fourth string falls upon the Bass Foot

of the Bridge. CONTENTS SECTION

I.—THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE VIOLIN. SECTION II.—THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE VIOLIN. ITALIAN AND OTHER STRINGS. SECTION

III.—THE ITALIAN SCHOOL. THE ITALIAN VARNISH. THE ITALIAN

MAKERS . |

||||||||||||||||||||||