CHAPTER I. The Roman and Barbarian Worlds at the End of

the Fourth Century.

The End of

Ancient History. New Form of the Roman Empire.—Municipal Government. Curials.—Taxes.—Condition of Persons.—The Army.—Moral and

Intellectual Condition.— The Christian Church.—The Barbarians.—Germanic

Nations. —Slavs and Huns

CHAPTER II. First Period of Invasion (375-476). Alaric, Radagaisus, Gaiseric, and Attila.

First Movement

of the Barbarians before the Death of Theodosius.—Division of the Empire at

the Death of Theodosius (395).—Alaric and the Visigoths (395-419); the Great

Invasion of 406.—Founding of the Kingdom of the Burgundians (413), of the

Visigoths, and qf the Suevi (419).—Conquest of Africa

by the Vandals (431).—Invasion of Attila (451-453).—Taking of Rome by Gaiseric

(455).—End of the Empire of the West (476)

CHAPTER

III. Second Period of Invasion: the

Franks, the Ostrogoths, the Lombards and the Anglo-Saxons (455-569)

PA

A Second Invasion of German Barbarians Successful in founding States.—Clovis

(481-511).—The Sons of Clovis (511-561).— Conquest of

Burgundy (534) and of Thuringia (530). Theodoric and the Kingdom of the

Ostrogoths in Italy (493-526).—The Lombards (568-774).—Foundation of the

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (455-584)

CHAPTER

IV. The Greek Empire from 408 to 705; Temporary Reaction of the Emperors of

Constantinople against the Germanic Invaders.

Theodosius

II, Marcian, Leo I, Zeno, Anastasius, Justin I (408-

527).—Justinian I (527-565).—Wars against the Persians (528-533 and

540-562).—Conquest of Africa from the Vandals (534); of Italy from the

Ostrogoths (535-553); Acquisitions in Spain (552); Justinian’s Administration

of the Interior; Code and Digest.—Justinian II, Tiberius II, Maurice and

Phocas (565-610); Heraclius (610-641); Decline of the Greek Empire

CHAPTER

V. The Renewal of the German Invasion by

the Franks. Greatness of the Merovingians.—Their Decadence (561-687).

Power

of the Merovingian Franks New Character of their History.— Lothaire I, Fredegonda and Brunhilda.— Lothaire II (613-628).— Dagobert (628-638).— Preponderance of Franks in Western

Europe.— Customs and Institutions introduced by the Germans among the

Conquered Peoples.— Laws of the Barbarians.—Decline of the Royal

Authority; the “ Rois Faineants.”—Mayors of the

Palace.—The Mayor Ebroin (660) and Saint Leger;

Battle of Testry(687).—Heredity

of Benefices

CHAPTER

VI. Mohammed and the Empire of the Arabs (622-732).

Arabia

and the Arabs.—Mohammed.—The Hegira(622); Struggle with the Koreishites (624); Conversion of Arabia.—The Koran.—The First Caliphs of Persia

and of Egypt; Conquest of Syria (623-640).—Revolution in the Caliphate,

Hereditary Dynasty of the Ommiads (661-750).—Conquest

of Upper Asia (707) and of Spain (711)

CHAPTER

VII. Dismemberment, Decline and Fall of the

Arabian Empire (755-i°58).

Accession

of the Abbasides (750), and Foundation of the

Caliphate of Cordova (755).—Caliphate of Bagdad (750-105S).— Almanssur, Haroun-al-Rashid, Al-Mamun.— Creation of the Turkish Guards. Decline and

Dismemberment of the Caliphate of Bagdad.—Africa; Fatimite Caliphate (968).—Spain; Caliphate of Cordova.—Arabian Civilization

CHAPTER

VIII. The Mayors of Austrasia and the Papacy,

or the Efforts to Infuse Unity into the State and the Church.

Pippin

of Heristal (687-714).—Charles

Martel (714-741); The Carolingian Family reorganizes the State and its

Authority. —Formation

of Ecclesiastical Society; Elections; Hierarchy; the Power

of the Bishops.—Monks; Monasteries; the Rule of St. Benedict.—The Pope; St.

Leo; Gregory the Great.— The Papacy breaks away from the Supremacy of Constantinople

(726); invokes the Aid of Charles Martel.—Pippin the Short (741-768)

CHAPTER

IX. Charlemagne; Unity of the Germanic

World.—the Church in the State (768-814).

The

Union, and the Attempted Organization A the Whole Germanic World under

Charlemagne.—Wars with the Lombards (771-776).—Wars with

the Saxons (771-804).—Wars with the Bavarians (788), the Avars (788-796),

and the Arabs of Spain (778-812): the Extent of the Empire.—Charlemagne comes

Emperor (800).—Results of his Wars.—Literary Revival

CHAPTER

X. LOUIS the Pious and the

Treaty of Verdun (815-843).

Instability

of Charlemagne’s Work.—Louis the Pious (814-840); his

Weakness; Division of the Empire.—Revolt of the Sons of

Louis the Pious.—Battle of Fontenay (841); Treaty of Verdun

(843)

CHAPTER

XI. Final Destruction of the Carolingian

Empire (845-887).

Internal

Discords; Vain Effort of the Sons of Louis the Pious to reconstitute the

Empire.—Division

of the Royal Authority; Heredity of Benefices and of Offices.—Louis the

Stammerer (877)—Louis III, and Karlmann (879);

Charles the Fat (1884)

CHAPTER

XII. The Third Invasion, in the Ninth and

Tenth Centuries.

The

Norsemen in France and England.—In the Polar Regions and in Russia.—The

Saracens.—The Hungarians.—Difference between the Ninth Century Invasion and

those preceding

CHAPTER

XIII. France and England (8S8-1108); Decline of the Royal Power

in France. Increase of the National Power.—Norman Conquest of England (1066).

The

Struggle of a Century between the Last Carolingians and the First of the

Capetian Dynasty.—The Accession of Hugh Capet (987).—Weakness

of the Capetian Dynasty: Robert (996); Henry I. (1031); Philip I

(1060).—Activity of the French Nation.—Downfall of the Danish Dynasty in

England (1042); Eadward the Confessor.—Harold

(1066).—The French Invasion of England.—Battle of Hastings (1096).—Revolts

of the Saxons aided by the Welsh (1067) and the Norwegians (1069). —Camp of

Refuge (1072); Outlaws.—Spoliation of the Conquered.—Results of

this Conquest

CHAPTER

XIV. Germany and Italy (888-1039).—Revival of the Empire of Charlemagne by the German

Kings.

Extinction

of the Carolingian Family in Germany (911).—Election of Conrad I. (911), and of

Henry the Fowler (919); Greatness of the House of Saxony.—Otto I, or the Great

(936); his Power in Germany; he drives out the Hungarians (955).—Condition

of Italy in the Tenth Century.—Otto re-establishes the Empire (g62).Otto II,

Otto III, Henry II (973-1024), and Conrad II (1024-1039)

CHAPTER

XV. Feudalism.

Beginning

of the Feudal Regime.—Reciprocal Obligations of Vassal and

Lord.—Ecclesiastical Feudalism.—Serfs and Villeins. —Anarchy and

Violence; Frightful Misery of the Peasants; Several Goods Results.—Geographical

Divisions of Feudal Europe

CHAPTER

XVI. Civilization in the Ninth and Tenth

Centuries.

Charlemagne’s

Fruitless Efforts in Behalf of Literature.—Second Renaissance after the Year

1000.—Latin

Language.—Language

of the Common People.—Chivalry, Architecture

CHAPTER XVII. The Quarrel over Investitures (1059-1122).

Complete

Supremacy of the Emperor Henry III. (1039-1056).— Hildebrand’s Effort to

regenerate the Church and emancipate the Papacy; Regulation of 1059.—Gregory

VII. (1073). His Great Plans.—Boldness of his First Acts.—Humiliation of the

Emperor (1077).—Death of Gregory VII. (1085), and of Henry IV. (1106). Henry V

(1106).—The Concordat of Worms (1122); End of the Quarrel over Investitures

CHAPTER

XVIII. Struggle between Italy and Germany (1152-1250).

Three

Epochs in the Struggle between the Papacy and the Empire. —Strength

of German Feudalism; Weakness of Lothar II (1125); the Hohenstaufen

(1138).—Division of Italy; Progress of the Small Nobles and of the Republics.—Arnold

of Brescia (1144).—Frederick I., Barbarossa (1152); Overthrow of Milan (1162);

the Lombard League (1164); Peace of Constance (1183).—Emperor

Henry VI. (1190); Innocent III. (1198); Guelfs and Ghibellines in

Italy.—Frederick II. (1212-1250).— Second Lombard League (1226).—Innocent IV.

(1243); Fall

of German Power in Italy (1250)

CHAPTER

XIX. The First Crusade to Jerusalem (1095-1099).

Condition

of the World before the Crusades; the Greek Empire.— Peter the Hermit; the

Council Of Clermont (1095) and the first Crusaders.—Departure

of the Great Army of Crusaders (1096); Siege of Nicaea and Battle of Dorylaeum.—Siege

and Taking of Antioch (1098); Defeat of Kerboga;

Siege and Taking of Jerusalem (1099).—Godfrey, Baron of the Holy Sepulchre.— Organization of the New Kindgom

CHAPTER

XX. The Last Crusades in the East; Their

Results (1147-1270).

Second

Crusade (1147).—Jerusalem taken by Saladin; Third Crusade (1189).—Fourth Crusade

(1201-1204).—Foundation of an Empire at Constantinople (1204-1261).—The last

Four Crusades in the East; the Mongols of Jenghiz Khan.—Seventh and Eight Crusades (1248 and 1270).—Effects of the Crusades

CHAPTER

XXI. The Crusades of the West.

The

Crusades in Europe; the Teutonic Order (1230).—Conquest and Conversion of

Prussia, Livonia, and Esthonia.—Crusade against the

Albigenses (120S); Union of Southern and Northern France.—The

Spanish Crusade.—Decline of the Caliphate of Cordova during the Ninth Century;

its Renewed Strength during the Tenth Century, and its Dismemberment in the

Eleventh Century. Formation of the Kingdoms of Castile and Leon, of Navarre,

and of Aragon. Taking of Toledo (1085); Founding of the County of Portugal

(1095); the Cid.— Incursions of the Almoravides (1086), and of the Almohades (1146).—Victory

of Las Navas de Tolosa (1211). The Moors driven back upon Granada.—Results of the Spanish Crusade 290

CHAPTER

XXII. Progress of the Cities.

Beginnings

of the Communal Movement —Communes properly so called.—Intervention of Royalty;

Decline of the Communes.— Cities not Communal.—Origin of the Third Estate.—Advancement of

City Populations in England and Germany.—Feudal Rights and Customary Rights

opposed

CHAPTER

XXIII. Civilization of the Twelfth and

Thirteenth Centuries.

Explorations

in the East and the Commerce of the Middle Ages.— New Departures in Industry

and Agriculture.—Corporations. —Condition of the Country Districts.—Lack of

Security.—The Jew and Bills of Exchange.—Intellectual Progress; Universities,

Scholastics, Astrology, Alchemy, Magicians.—National

Literature.—Arts;

Ogival Architecture

BOOK EIGHT

RIVALRY BETWEEN ‘FRANCE AND ENGLAND (1066-14531)

Louis

the Fat (1108-1137); William II and Henry I (1087-1135). —Louis VII (1137-1180)

in France; Stephen and Henry II. (1135-1189) in England.—Abuse of Ecclesiastical

Jurisdiction.—Thomas 4 Becket (1170).—Conquest of Ireland (t 1717; the King of France sustains

the Revolt of the Sons of the English King (1173).—New

Character shown by French Royalty in the Thirteenth Century; Philip Augustus

(1180) and Richard the Lion-hearted (1189).—Quarrels between Philip Augustus

and John Lackland; Conquest of Normandy and of Poitou (1204).—Quarrel between

John Lackland and Innocent III (1207). —Magna Charta

(1215) .

Internal

Administration of Philip Augustus.—Louis VIII (1223) and the Regency of Blanche

of Castile. — Saint Louis, his Ascendency in Europe; Treaties with England

(1259), and with Aragon (1258).—Government of Saint Louis.—Progress of the

Royal Authority.—New Character of Politics; Philip III (1270), Philip IV.

(1285); New War with England (1294).—A New Struggle between the Papacy and the

State (1296-1304).— The Papacy at Avignon (1309-1376).—Condemnation of the

Templars (1307).— Administration of Philip IV; Reign of his Three Sons

(1314-1328)

Pledges made by

the Magna Charta (1215).—Henry III. (1216).— The League of the Barons;

Provisions of Oxford; the Parliament (1258).—Edward I (1272).—Conquest of

Wales (1274- 1284).—War with Scotland (1297-1307); Balliol, Wallace, and

Bruce.—Edward II. (1307); Progress of Parliament

Preliminaries

of the Hundred Years War (1328-1337).—Battle of Sluys (134o); State of Affairs in Brittany.—Crecy (1346) and Calais (1347).—John

(1350); Battle of Poitiers; States General; the Jacquerie; Treaty of Bretigny (1360).—Charles V. (1364); Du Guesclin; the Great

Companies in Spain.—The War with the English renewed (1369); New

Method of Warfare.—Wycliffe.—Wat Tyler and the English King Richard IE (1377)-—Deposition

of Richard II and Accession of Henry IV of Lancaster (1399).—Henry V

(1413).—France under Charles VI (1380-1422); Popular Insurrections.—Insanity of

Charles VI. (1392); Assassination of the Duke of Orleans (1407);

the Armagnacs and the Burgundians.—Henry V reopens the War with the French

(1415).—Battle of Agincourt. —Henry VI and Charles VII, Kings of France (1422);

Joan of Arc (1421-1431).—Treaty of Arras (1435); Charles VII at Paris (1436);

End of the Hundred Years War

Parliament’s

Increasing Power in England.—The English Constitution in the Middle of the Fifteenth

Century.— France: Progress of Royal Authority.—Formation of a Princely

Feudalism by Appanages.—Development of the Old and New institutions

BOOK

NINE

ITALY,

GERMANY, AND THE OTHER EUROPEAN STATES TO THE MIDDLE OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

CHAPTER

XXIX. Italy from 1250 to 1453.

Italy

after the Investiture Strife; Complete Ruin of all Central power (1250).—Manfred

and Charles of Anjou.—The Principalities in Lombardy; Romagna and the

Marshes.—The Republics: Venice, Florence, Genoa, and Pisa.—Reappearance of the

German Emperors in Italy and the Return of the Popes to Rome.—Anarchy;

the Condottiere.—Splendor of Literature and the

Arts.—Dante,

Petrarch, Boccaccio

.CHAPTER

XXX. Germany from 1250 to 1453,

The Great Interregnum (1250-1273).—Usurpation of Imperial Property and

Rights.—Anarchy and Violence; Leagues of the Lords and of the Cities.—Rudolf of Hapsburg

(1273).—Founding of the House of Austria (1282).—Adolf of Nassau (1291) I and Albert of Austria (1298).—Liberation of Switzerland (1308). -Henry

VII (1308) and Lewis of Bavaria (1314).—The House of Luxemburg (1347-1438); the

Golden Bull.—The House of Austria recovers the Imperial Crown, but not its

Power (1438)

CHAPTER

XXXI. The Spanish, Scandinavian, and Slavic

States.

Spain

from 1252 to 1453.—The Crusade suspended.—The Scandinavian States, Denmark,

Sweden and Norway; their Secondary Role after the Time of the Norsemen.—Slavic

States; Power of Poland; Weakness of Russia.—Peoples of

the Danube Valley; the Hungarians.—The Greek Empire.—The Ottoman Turks and the

Mongols of Timour

BOOK

TEN

CIVILIZATION

IN THE LAST CENTURIES OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

CHAPTER

.XXXII. The Church from 1270 to 1453.

Foreshadowings of a New Civilization.—The

Papacy from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII.—The Popes at

Avignon (1309—1376) ; Great Schism of the West (1378-1448).—Wycliffe, John

Huss, Gerson; Councils of Pisa (1409), of Constance (1414), and of Basel

(1431); Gallican Doctrines

CHAPTER

XXXIII. The National Literatures.—The

Inventions of the Middle Ages.

The

Italian and French Literatures.—The Literatures of the North. —English, German,

and Scandinavian.—Spanish and Portuguese Literatures.—Renaissance of Classical

Learning.—Printing, Oil-painting, Engraving, and Gunpowder

THE HISTORY

OF

THE MIDDLE AGES

AUTHOR’S

PREFACE.

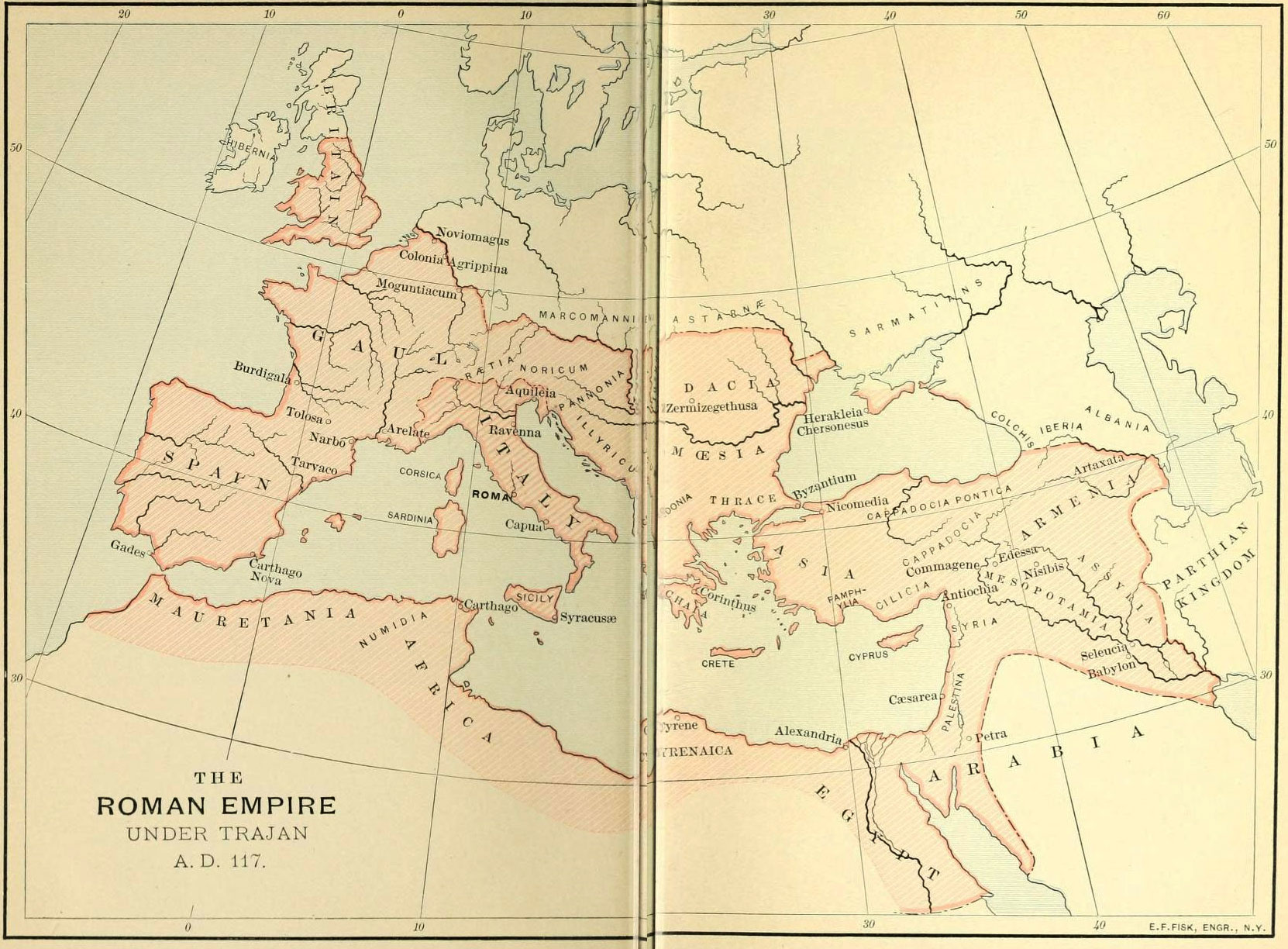

The term Middle Ages is applied to the time which elapsed between the fall of the

Roman Empire and the formation of the great modern monarchies, between the

first permanent invasion of the Germans, at the beginning of the fifth century

of our era and the last invasion, made by the Turks, ten centuries later, in

1453.

During this

interval between ancient and modern times the pursuit of learning and of the

arts was almost entirely suspended. Instead of the republics of antiquity and

the monarchies of the present day, a special political organization was

developed which was called feudalism : this consisted in the rule of the lords.

Though every country had its king, it was the military leader who was the real

ruler. The central power was unable to assert itself and the local powers were

without supervision or direction. Hence this epoch was different in every

respect from those which preceded and followed it, and it is on account of this

difference in character that we give it a special name and place in universal

history.

The history of

the Middle Ages is generally disliked by those who are obliged to study it, and

sometimes even by those who teach it. It seems to them like a great Gothic

cathedral, where the eye loses itself in the infinite details of an art which

is without either unity or system, or like an immense and confused book which

the reader spells out laboriously but never understands. If, however, we are

content to confine this history to the significant facts which alone are worth

remembering, and to pass over the insignificant men and events, giving

prominence and attention to the great men and great events, we shall find this

period to be as simple as it is generally considered confusing.

In the first

place, we must define its limits. The true history of the Middle Ages does not

extend beyond the ancient Roman Empire and the provinces added to it by Charlemagne

when he brought the whole of Germany under one common civilization. Outside of

these limits all was still barbarism, of which little or nothing

can be known, and whose darkness is only occasionally relieved by a gleam from

the sword of a savage conqueror, a Tchingis-Khan, or

a Timour. The events which interest us and which

exerted an active influence on the development of the modern nations took place

within these limits. And even among these events we need only remember those

which characterize the general life of Europe, not the

individual, isolated life of the thousand petty States

of which the historian as well as the poet can say :

“ Non ragioniam di lor ; ma guarda, e passa.”

The

Middle Ages were built on the ancient foundation of pagan and Christian Rome. Hence our first

task is to study the Roman world and examine the

mortal wounds it

had suffered; to pass in review this empire, with so many

laws but no institutions, with so many subjects but no

citizens, and with an administration which was so elaborate

that it

became a crushing burden ; and, finally, to conjure up before us this

colossus of sand, which crumbled at the touch of paltry foes, because,

though it contained a religious life, eager for heavenly things,

it was inspired by no strong political life such as is necessary for the

mastery of the earth.

Beyond

the Empire lay the barbarians, and in two currents of invasion they rushed

upon this rich and unresisting prey. The Germans seized the provinces of the

north ; the Arabs those of the south. Between these mighty streams,

which flowed from the east and the west, Constantinople, the decrepit daughter

of ancient Rome, alone remained standing, and for ten centuries, like a rocky

island, defied the fury of the waves.

With

one bound the Arabs reached the Pyrenees, with a second the Himalayas, and the

crescent ruled supreme over two thousand leagues of country, a territory of

great length, but narrow, impossible to defend, and offering many points of

attack. The Caliphs had to contend against a mighty force in the geographical

position of their conquests, a force which is often fatal to new-born States,

and which in this case destroyed their Empire and at the same time brought ruin

to their equally brilliant and fragile civilization.

Many

chiefs among the Germans also called into being States which were only

ephemeral, because they arose in the midst of this Roman world, which was too

weak to defend itself but strong enough to Communicate to all with whom it came

in contact the poison which was working in its own veins. To this fact we may

attribute the fall of the kingdoms of Gaiseric, Theodoric, and Aistulf; of the Vandals, the Heruli,

and the eastern and western Goths.

One

people alone fell heir to the many invaders who entered the Empire by means of

the Rhine and the Danube, namely, the Franks. Like a great oak, whose roots

grow deep down in the soil which bears and nourishes it, they kept in constant

communication with Germany and drew thence a barbarian vigor which continually

renewed their exhausted powers.

Though

threatened with an early decline under the last Merovingians, they revived

again with the chiefs of the second dynasty, and Charlemagne tried to bring

order into chaos and throw light into darkness by organizing his dominions

around the throne of the Emperors of the west, and by binding to it Germanic

and Christian society. This was a magnificent project and one which

has made his name worthy to be placed by the side of the few before which the

world bows. But his design, which was incapable of accomplishment, not only

because geography was against it, as it was against the permanence of the

Arabian Empire, but because all the moral forces of the times, both the instincts

and the interests of the people, were opposed to its success. Charlemagne

created modern Germany, which was a great thing in itself, but the day when he

went to Rome to join the crown of the Emperors to that of

the Lombard kings, was a fatal day for Italy. From that time this beautiful

country had a foreign master, who lived far away and only visited her

accompanied by hordes of greedy and barbarous soldiers, who brought ruin in

their train. How much blood was shed during centuries in the attempt to

maintain the impossible and ill-conceived plan of Charlemagne. How many of the

cities and splendid monuments of the country were reduced to ruins, not to

mention the saddest thing of all, the ruin of the people themselves and of

Italian patriotism.

After

the ninth century the Carolingian Empire tottered and fell through the

incompetency of its chiefs, the hatred of the people, and the blows of a new

invasion led by the Norsemen, the Hungarians, and the Saracens. It separated

into kingdoms, and these kingdoms into seignories. The great political

institutions crumbled into dust. The State was reduced to the proportions of a

fief. The horizon of the mind was equally limited ; darkness had fallen upon

the world; it was the night of feudalism.

A few great

names, however, still survived: France, Germany and Italy; and great titles

were still worn by those who were called the kings of these countries. These

men were kings in name but not in truth, and were merely the symbols of a

territorial unity which existed no longer, and not real, active, and powerful

rulers of nations. Even the ancient Roman and Germanic custom of election had

been resumed.

Of these three

royal powers, one, that of Italy, soon disappeared ; the second, that of

France, fell very low ; while the third, that of Germany, flourished vigorously

for two centuries after Otto I had revived the Empire of Charlemagne, though

on a small scale. Just as the sons of Pippin had reigned over fewer peoples

than Constantine and Theodosius, the Henrys, Fredericks, and Ottos reigned

over a smaller territory than Charlemagne and with a less absolute power.

By

the side of and below the kingdoms born of invasion there arose a power of

quite a different character, and one which did not confine itself to any

limits, whether of country or of law. The Church, emerging wounded

but triumphant from the catacombs and the Roman amphitheatres,

had gone out to meet the barbarians, and at her word

the Sicambrian meekly bowed his head. She only sought a spiritual

kingdom ; she also gained an earthly one. Power came to her unsought, as it

comes to every just and righteous cause which aids the advance of humanity

toward a better future. After establishing the unity of her dogma and of her hierarchy,

her chiefs attained the highest eminence in the Catholic world, whence they

watched, directed, and restrained the spiritual movements inspired by them.

The

Church strove to teach mildness to a violent and lawless society, and, opposed

to the feudal hierarchy, the equality of all men; to turbulence, discipline; to

slavery, liberty; and to force, justice. She protected the slave from his

arrogant master, and defended the rights of women, children, and the

family against the fickle husbands who did not draw back even from divorce and

polygamy. The only succession recognized by the States in their public offices

was succession by right of inheritance; the Church set the example of

succession by right of intellectual superiority, by the election of her

abbots, bishops, and even her pontiff, and serfs succeeded to the chair of St.

Peter, thus attaining a dignity higher than that of kings. The barbarians had

demolished the civilization of antiquity ; the Church preserved its fragments

in the seclusion of her monasteries. She was not only the mother of creeds,

but was also the mother of art, science, and learning. Those great scholars who

taught the world to think again, those maîtres es pierres vives, who gave Christianity its most wonderful movements, were sons of the

Church.

The feudal

princes and lords, when freed from feudal slavery, thought themselves above all

law because they had put themselves beyond the reach of resistance; but the

Popes used the weapons of the Church against them. They excommunicated a

usurper of the throne of Norway, a king who falsified the coinage in Aragon,

the treacherous and foresworn John in England and in France Philip Augustus,

when he repudiated his wife the day after his marriage. During the rule of

force the Popes had become the sole guardians of the moral law and they

recalled these princes, who transgressed against it, to their duty by releasing

their people from their oath of fidelity. The pontifical power spoke in the

name and place of popular right.

This great

moral force, however, was not always mistress of herself. Until 726 the

pontiffs had been the subjects of the Emperors of Rome, western or eastern.

Charlemagne claimed and wielded the same authority over them. His successors,

the German emperors, tried to follow his example. Henry III deposed three

Popes and in 1046 the council of Sutri once again

recognized that the election of no sovereign pontiff could be valid without the

consent of the emperor.

But after

Charlemagne’s death the Church constantly grew in power. Her possession of a

large part of the soil of Christian Europe gave her material force ; while the

fact that all, both great and small, obediently received her command, gave her

great moral force; these two forces, moreover, were increased tenfold by the

addition of a third, namely, unity of power and purpose; at the time of the

Iconoclasts and the last Carolingians, the sole aspiration of the Church had

been to escape from the bonds of the State and to live a free life of her own.

When she became stronger and, of necessity, more ambitious, she claimed the right,

after the manner of all powerful ecclesiastical bodies, to rule the lay part of

society and the civil powers.

Two powers,

accordingly, stood face to face at the end of the eleventh century, the Pope of

Rome and the German emperor, the spiritual and the temporal authorities, both

ambitious, as they could not fail to be in the existing state of morals,

institutions, and beliefs. The great question of the Middle Ages then came up

for solution: Was the heir of St. Peter or the heir of Augustus to remain

master of the world ? There lay the quarrel between the priesthood and the

empire.

This quarrel

was a drama in three acts. In the first act the Pope and the emperor disputed

for the supremacy over Christian Europe; in the Concordat of Worms (1122) they

made mutual concessions and a division of powers, which has been confirmed by

the opinion of modern times ; in the second act, the main question to be solved

was the liberty of Italy, which the Popes protected in the interest of their

own liberty; in the third act, the existence of the Holy See was in peril; the

death of Frederick II saved it.

The result of

this great struggle and far-reaching ambition was the decline and almost the

ruin of the two adverse powers. The papacy fell, shattered, at Avignon, and the

Babylonian captivity began, while the German Empire, mortally wounded, was at

the point of disappearing during the Great Interregnum, and only escaped

destruction to drag out a miserable existence.

During the

contest the people, recovering from their stupor, had turned to seek adventure

in new directions. Religious belief, the most powerful sentiment of the Middle

Ages, had led to its natural result; it had inspired the crusades and had sent

millions of men on the road to Jerusalem.

Though the crusade

was successful in Europe against the pagans of Prussia and the infidels of

Spain, and, accompanied by terrible cruelty, against the Albigenses of France,

it failed in its principal object in the East the Holy Sepulchre remained in the hands of infidels and Europe seemed in vain to have poured out

her blood and treasure in the conquest of a tomb which she was not able to

keep. Nevertheless, she had regained her youth ; she had shaken off a mortal

torpor, to begin a new existence, and the roads were now crowded with

merchants, the country covered with fruitful fields, and the cities filled

with evidences of her growth and power. She created an art, a literature and

schools of learning, and it was France which led this movement. The Middle Ages

had come to an end when the successors of Charlemagne and of Gregory VII

became powerless, when feudalism tottered to its fall and when the lower

classes threw off their yoke ; new ideas and new needs arising proclaimed the

advent of Modern times.

These new needs

were represented by the two countries, where they were most fully met, namely,

France and England. The England of today dates from the Magna Charta of King

John, just as the royal power of Louis XIV came directly from Philip Augustus

and St. Louis. We find in these two countries three similar elements : the

king, the nobles, and the people, but in different combinations. From this

difference in combination resulted the difference in their histories.

In England the

Conquest had made the king so strong that the nobles were obliged to unite with

the commons in order to save their honor, their estates, and their heads. The

nobility favored popular franchises, which they found necessary to their cause; the people were attached to their feudal lords, who fought for them. English

liberty, sprung from the aristocracy, has never been unfaithful to its origin,

and we have the curious spectacle of a country in which the greatest freedom

and the greatest social inequalities exist side by side.

In France, it

was the king and the people who were oppressed ; they were the ones to unite,

in order to overthrow the power of feudalism, their common enemy : but the

rewards of victory naturally fell to the share of the leader in battle. This

twofold tendency is evident from the fourteenth century. At the beginning of

that century, Philip the Fair leveled the castles with the ground, called

peasants to participate in his councils, and made every one, both great and

small, equal in the eye of the law ; at the end of it the London parliament

overthrew its king and disposed of the crown.

If these two

countries had not fallen upon each other in the violent struggle which is

called the Hundred Years War, the fourteenth century would have seen them fairly

started in their new life.

Germany and

France have a common-starting point in their histories : each arose from the

ruins of the great Carolingian Empire, and each was originally possessed of a

powerful feudal system ; consequently their subsequent careers might have been

the same. In one, however, the royal power reached its apogee ; in the other it

declined, grew dim, and disappeared. There was no mystery in this ; it was a

simple physiological fact for which no reason can be given. The Capetian

family did not die out. After the lapse of nine centuries it still continued to

exist; by this mere fact of continuance alone the custom of election was not

suffered to become established, as there was no occasion for its use. The

dynasties on the other side of the Rhine, on the contrary, though at first

abler and stronger, seemed to be cursed with barrenness. At the end of two or

three generations they became extinct; eighteen royal houses can be counted in

five centuries ; that is to say, that eighteen times the German people saw the

throne left vacant, and were obliged to choose an occupant from a new family.

Succession by election, which had been one of the customs of Germany and which

the Church had retained, became a regular system. The feudal chiefs were not

slow to understand what advantages the system had for them; at each election,

to use an expression of the day, they plucked a feather from the imperial

eagle, and Germany finally counted a thousand princes; while on the other side

of her great river, the heir of Hugh Capet could say with truth, “ I am the

State.”

Such were the

three great modern nations, as early as the fourteenth century : Great Britain,

with its spirit of public liberty and hereditary nobility ; France, with a

tendency toward civil equality and an absolute monarchy; Germany, toward

independent principalities and public anarchy. Today, the one is virtually an

aristocratic republic, the other a democratic State, and the third was until

lately a confederation of sovereign States ; this difference was the work of

the Middle Ages.

In Spain, the

Goths who had fled to the Asturias had founded there a Christian kingdom;

Charlemagne had marked out two more, by forcing a passage through the Pyrenees

at two points, Navarre and Catalonia. These three States, strongly protected by

the mountains at their back, had advanced together toward the south against the

Moors; but modern times had already begun on the north of the Pyrenees, while

the Spaniards, in the peninsula, had not finished their crusade of eight

centuries. They gave as yet no sign of what was to be their subsequent career.

The other

Neo-Latin people, the Italians, had not been able to find in the Middle Ages

the political unity which alone constitutes the individuality of a great

nation. There were three obstacles in the way of this: the configuration of the

country, which did not offer a geographical center ; the thousand cities which

ancient civilization had scattered over its surface, and which had not yet

learned by bitter experience to surrender a part of their municipal independence

to save the common liberty ; finally, the papacy, which, owning no master, even

in temporal affairs, laid down this principle, very just from its point of view

and entirely legitimate in the Middle Ages, namely, that from the Alps to the

Straits of Messina there should never be one sole power, because such a power

would certainly desire Rome for its capital. This policy lasted for thirteen

centuries. It was the papacy which, as early as the sixth century, prevented

the consolidation of the Italian kingdom of the Goths; and, in the eighth

century, the formation of that of the Lombards ; which summoned Pippin against Aistulf, Charlemagne against Desiderius, Charles of

Anjou against Manfred; as well as later the Spaniards, the Swiss, and the

Imperialists against the French; the French against the Spaniards ; which

finally entered into compacts with all the foreign masters of the peninsula in

order to assure, by a balance of influences and forces,

the independence of her little domain and her authority.

Italy,

having no central power, was covered with republics, most of which, after a

time, developed into principalities. The life there was brilliant, but corrupt,

and the civic virtues were forgotten. Anarchy dwelt in her midst, an infallible

sign that the foreigner would again become her master.

In

the North, utter darkness: Prussia and Russia are of yesterday. But in the

East there appeared a nation, the Turks, which was formidable since it

possessed what Christian Europe no longer had, the

conquering spirit of religious proselytism, which had been the spirit of the

crusades ; and also what Europe did not yet possess, a strong military

organization.

Accordingly

this handful of nomad shepherds, which had so suddenly become a people, or

rather an army, accomplished without difficulty the last invasion ;

Constantinople fell. But at the

very moment when the last remaining fragment of the Roman Empire disappeared,

the genius of ancient civilization arose, torch in hand, from the midst of the

ruins. The Portuguese were on the road to the Cape of Good Hope, while the

artists and authors were opening the way to the Renaissance : Wycliffe

and John Huss had already, prepared the road for Luther and Calvin. The changes

at work in the States corresponded to the change in thought

and belief. Reform was demanded of the Church ; shaken by

schism, she refused it; in a century she had to deal with a revolution.

The

important facts to be noted are :

The

decline of the Roman Empire and the successful accomplishment of two invasions

; the transient brilliancy of the Arabian civilization.

The

attempted organization of a new Empire by Charlemagne,

and its dissolution.

The

rise and prevalence of feudalism.

The

successive Crusades.

The

contest between the Pope and the Emperor for the sovereignty of the world.

We

have here the real Middle Ages, simple in their general outline, and reaching

their highest development in the thirteenth century.

But

even before this period a new phase of the Middle

Ages

had appeared in England and France; which led to a new social organization of

the two countries. Soon a few brave voices were heard discussing the merits of

obedience, of faith, even, and pleading the cause of those who, until that

time, had been of no account, the peasants and the serfs.

Humanity,

that tireless traveler, advances unceasingly, over vale and hill, today

on the heights, in the light of day, tomorrow in the valley, in darkness and

danger, but always advancing, and attaining by slow degrees and weary efforts

some broad plateau, where he pauses a moment to rest and take breath.

These

pauses, during which society assumes a form which suits it for the moment, are

organic periods. The intervals which separate them may be called inorganic

periods or times of transformation. On these lines we may divide the ten

centuries of the Middle Ages into three sections : from the fifth to the tenth

century, the destruction of the past and the transition to a new form ; from

the tenth to the fourteenth, feudal society with its customs, its

institution, its arts, and its literature. This is one of the organic periods

in the life of the world. Then the tireless traveler starts again : this time

he again descends to depths of misery to reach, on the other side, a country

free from brambles and thorns. When the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are

crossed we already perceive from afar the glorious forms of Raphael,

Copernicus, and Christopher Columbus, in the dawn of the new world.