THE HISTORY OF MUSIC (art and Science) FROM THE EARLIEST RECORDS TO THE FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRECHAPTER XII.

Stringed

instruments

Of stringed instruments much has already been said

incidentally. As to the different sizes, and different kinds of Lyre, Aristides

Quintilianus classifies them in the following manner: First, the parent Lyre, as the most masculine, on account of its low and

rough tones. This was therefore the largest kind of Lyre, and probably was

often on a stand, as its name agrees with that of a fixed star. Next to it, the

Kithara, as a little less low and rough, but not differing materially from the

Lyre. The Kithara was a portable instrument, and as the quality of yielding low

sounds must depend mainly upon length of string, it may be ranked as rather

less in size than the Lyre proper. It is now indistinguishable from the

Phorminx, which was also portable; but a third kind, the Chelys,

derives its name from its having had a shell back. Aristides passes on from the

Kithara to the Polyphthongos, or many-sounding Lyre. This is elsewhere termed the Polychordon, or many-stringed,

and is equivalent to the Barbitos, or Asiatic Lyre.

Anacreon preferred instruments of many strings, and he refers to the Barbitos, as of the lyre kind. We know that Greek lyres had

not attained to many strings in his time. Horace likewise alludes to the Barbitos as a Lesbian instrument, and devotes it to the

hands of Polyhymnia. (Ode I.)

If neither Euterpe withhold her double pipe, nor

Polyhymnia flee away to strain the Lesbian Barbiton.

Theocritus describes the Barbiton as many-stringed,

and Euripides again makes it a synonym for lyre. Aristides describes the Polyphthongos as of a feminine character, in contrast to

the larger Lyre and to the Kithara, as masculine. It is hardly to be doubted

that the instrument which is seen in the hands, of the young girl at p. 118,

where she is reading music from a scroll or book, is the Polyphthongos or Barbitos. The description as feminine means

that it yielded higher sounds than the larger instruments, which had also fewer

strings.

The following representation of Terpsichore, with a

lyre, is from Herculaneum. As the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, by which both

Herculaneum and Pompeii were overwhelmed, took place in the year 79, the

representation cannot be of later date than the first century of the Christian

era. The lyre is of the more poetical kind fit for recitation, but of very little use for music, in our sense of the

word.

The wood of the crumbling Greek Lyre in the British

Museum is sycamore; and it is noteworthy that the Egyptian Lyre in the Berlin

Museum, and the two in the British Museum, are of the same wood.

The most feminine, or highest sounding of lyres,

according to Aristides, was the Sambuca.

Strabo says that this name is barbarian; the Phoenicians, the

Parthians, the Scythians, and the Troglodytes or cave-dwellers, have in turn

had the credit of the invention. The last were a wise people to have made their

homes under ground, when they had such a country to inhabit as the borders of

the Red Sea. The Parthian and the Troglodyte instruments are said to have had

but four strings. We may suppose this kind to have been the little Trigon.

Aristides does not name the Phoinix nor the Atropos,

but they must have had many strings, for Aristotle refers to them as magadizing, or octave-playing, instruments.6 According to

Semos of Delos, the ribs of the Phoinix were made of the palm tree. Among the

Etruscan antiquities in Sir William Hamilton’s collection, is the accompanying

representation of a small lyre of peculiar construction. It has a tail-piece

for the attachment of the strings; a bridge to raise them; and sound-holes for

the escape of the tone. The strings are seven in number, but virtually only

four, because, while the base string is but single, the others are Etruscan

Lyre, doubled. Six are placed closer together, in twos, so that the plectrum

could sweep from one to another. I find nothing like it among Greek

instruments, but the bridge, the tail-piece, and the sound-holes, are ancient

Egyptian. We find a bridge to the hieroglyphic lute on p. 62, and sound-holes

to one of those in the frontispiece, and again at p. 43.

THE TRIPOD OF PYTHAGORAS.

Athenaeus quotes a story told by Artemon, that

Pythagoras once strung the three sides of a Delphian tripod, such as was used

to support an ornamental vase, and that he tuned one side to the Dorian scale,

another to the Phrygian, and the third to the Lydian scale or mode. So far, all

was possible; but it is improbable that Pythagoras should have attempted it,

because there could be no tone from such a tripod, for it had no

sounding-board. The minuteness of the remaining part of the story proves the

whole to be a myth. Artemon adds that Pythagoras contrived a pedal to turn this

tripod, and that he twisted it about with such rapidity while he was playing,

that any one might have fancied he was hearing three players upon three

different instruments.

Pythagoras, at least, had ears; and no one possessed

of them could have tolerated such barbarisms as rapid changes from D minor into

E minor, and then into F sharp minor, and back again. Artemon admits that it is

uncertain whether such an instrument ever existed, and there can be no doubt

the story was fabricated by someone who had no knowledge of music. That,

indeed, would not preclude a painter from depicting such a tripod, and so the

curious may see the imaginary instrument copied into Dr. Burney’s History of

Music.

Another instrument, which demands a certain amount of

faith to believe in it, is depicted upon an ancient vase in the Munich

collection, No. 805. It is supposed to be in the hands of Erato, and it is

perhaps as mythical as the Mese. No sounding-board is shown, and, without one,

it could have no tone. The form does not even seem to admit of such an

addition.

There are many more ancient instruments for which we are indebted to the invention of painters and of sculptors. Some are made so heavy with ornament that any tone produced by the strings would have been inaudible at the distance of a few yards. Others are without sounding-boards. Apollo was in these respects a particularly unfortunate god. He had scarcely ever a lyre that would have been worth an obolus for its music.

PEKTIS, NABLA, AND PANDOURA

The Pektis is almost as

perplexing as the Sambuca. Sopater says that it had two strings. In that case,

it must have had a neck and a finger-board, like the hieroglyphic lute. But

then Diogenes, the tragic poet, says that it was harp-shaped. That was quite

another instrument, and one that had neither neck nor finger-board. Plato

supports the second description, by referring to it as a Trigon, or harp,

having many strings.0 Again, both Aristoxenus and Menaechmos identify the Pektis as

a kind of Magadis, and the former adds that it was

played with both hands, without the use of a plectrum. In those cases it was an

Egyptian harp. Anacreon and Sophocles ascribe this instrument to the Lydians.

The root of the name has seemingly to be sought in some language other than

Greek. The description of Sopater is irreconcilable with those of others; and,

further, there were also lyres and pipes called by the same name.

Again, as to the Greek Nabla, Euphorion distinguishes between the Nabla and the Pandoura. This is, perhaps, only as to name,

for, in the same sentence, he joins together the Baromos and the Barbitos,0 which two instruments, quotations from other authors seem to

identify. Sopater appears to attribute the Nabla to

the Phoenicians, when he alludes to the sounds produced by the hand upon the

neck, (the laryngophonos,) of the

Sidonian Nabla. Yet, Mustakos,

in The Slave, notices the emblem of the lotus painted upon the ribs

of the instrument. The lotus was the emblem of Lower Egypt, and the Phoenicians

were the corn carriers of Egypt. An instrument with ribs had, in all

probability, a back rounded like a lute, for that form alone would require to

be ribbed. It is probable, then, that the Nabla is

one of the two kinds of lute exhibited in Egyptian paintings, as in the

frontispiece to this book; and, possibly, Pandoura may be the Greek name for

the other.

And now, while on the subject of the ribs of an

instrument, which ribs would only be made for one rounded at the back, there is

an antique pantheistic gem of the second century, which exhibits both the

ribbed back and the receding head of the lute. It represents, perhaps, Osiris

as Apollo, with the seven rays, for the rising sun. On the head are the wings

of Hermes; under the chin, the moon; and at the back of the head of Apollo, the

trident of Neptune, and a lute, instead of the lyre, for Hermes. The gem is cut

in chalcedony, and is here copied from the collection of Gemme Antiche, by Causeus de la

Chausse, Rome. 4to. 1700. This is the earliest that I have yet observed with

the receding head, which distinguishes the lute.

With all the care that can be taken, and after every

word of the description has been studied, ancient musical instruments are a

difficult subject, and one of which but little can be gleaned. What can be said

of the Skindapsos? We know only that it

was a barbarian instrument, and that it had four strings. Again, the

Spadix, one of the same class, having high notes. The Pelex was a kind of psaltery, according to Julius Pollux, and the only guide to its

probable form is that the name also signifies a helmet.

GREEKS COMPARED TO EGYPTIANS.

Perhaps no one thing is more likely to strike the

reader in the foregoing account than the very limited amount of invention among

the Greeks, if there was even any at all, as to musical instruments. These seem

to be all Asiatic or African. Even the word lyre has not been

traced to a Greek root, and we have representations of many-stringed lyres in

Egyptian paintings before the Greeks were a nation. Again, the Dorian Mode was

the one upon which the Greeks prided themselves; and Herodotus, in tracing the

genealogy of the Dorians, makes them natives of Egypt; adding that, in this

respect, the Lacedaemonians resemble the Egyptians: their heralds, musicians,

and cooks, succeed to their fathers’ professions, so that a musician is the son

of a musician. We can find no new principle for stringed instruments discovered

by a Greek, nor anything new in pipes. All was ready-made for them, together

with their system of music. The Greeks were even inapt pupils; for, although

they had many strings ever before their eyes, they did but reduce the number,

after a time, to bring the instruments down to then-own level. They practised a certain amount of harmony, but not so much as

earlier nations. Cultivation of the ear is required to be able to appreciate

many different notes running together at one time, especially with different

qualities of tone. We read of no such combinations of instruments in Greece as

we see with our own eyes in Egypt; and Greek definitions of concord and of

discord are almost invariably limited to two simultaneous sounds. On a first

perusal of Greek authors on music, I had formed a much higher estimate of the

nation in comparison with others, than a subsequent more general acquaintance will

sustain.

If the following account of the present state of music

in Japan, as given by a recent visitor, may be relied on, the Japanese are now

very much in the condition of the earliest Egyptians and Greeks as to music,

and they, too, must have had a Hermes, or an Apollo, among them :

The music of the Japanese is worth extremely little.

To accompany the singers on the stage, they have an orchestra of twenty-one

performers. The Syamsia is the principal

instrument. It is a kind of guitar with three strings, two being toned in the

Octave, and the third in the dominant. The body of the instrument consists of

the shell of a turtle, in the cavity of which the sounds produced by the three

strings are re-echoed, the strings being set in movement by a small rod, made

of horn. From this wretched instrument, the reader may form an idea what the

others must be. The Japanese are not acquainted with harmony, and their

instruments are played either unisono, or in the Octave. As regards

intervals and rhythm, the poverty of their melody is such that no European

musician can possibly conceive it. The Japanese, nevertheless, listen with

pleasure to their music for hours together. Blind people are exceedingly numerous

in Japan, even if we leave out of consideration the beggars who feign

blindness. The bands which play at festivities and private parties are composed

of blind men.

Here we have actually the lyre of the Egyptian Hermes,

with the two outer strings sounding an Octave apart, and the middle string a

Fifth from the lower, and a Fourth from the upper. We have also the shell back

to the instrument, and a piece of horn for the plectrum. Thus, wherever music

is in its infancy, we may encounter the same kind of story again and again.

PARTS OF THE LYRE.

Before passing on to the many-stringed instruments,

such as harp and psaltery, something may be said about the appendages to the

lyre.

The magas, or bridge,

which was added to some kinds of lyre, and which is shown on the Etruscan lyre

at p. 298, was admittedly of barbarian origin. Hypolyrios has been also occasionally translated bridge, but its more precise meaning

seems to be the cross-reed, or fixed cross-bar, to which the lower ends of the

strings were attached in very early lyres, and not the movable bridge over

which strings were passed in order to raise them above the body of the

instrument. In many cases there was no sounding-board which could be in the way

of a hand on the strings, and so that which is strictly a bridge was not

necessary.

According to the Latin version of Julius Pollux, but

not at all according to the Greek, the Hypolyrios formed the sides of the lyre. The translator was led into that misconception by

adhering to the old manner of rendering the preposition anti by loco,

although, just as in a case before cited, it was in evident contradiction to

the sense of the whole passage.

The Greek lyre seems to have been tuned at the lower

end of the strings, and that part of the instrument to have had the name of the Chordotonon, or Batera. The Echeion was the sounding-board, or rather the

sounding part of the body.

The lower parts of the curved sides of the lyre were

called Angkones, and above them were the Pechees, or fore-arms, also called Ktenia,

for which Kerata, horns, were sometimes substituted.

The Zugon, (in Latin, Transtillum,)

was the cross-bar that yoked together the fore-arms, or horns, and along which

the upper ends of the strings were either tied, or otherwise fastened. In some

Egyptian lyres this crossbar sloped, and the strings were timed by sliding the

noose upwards, and so increasing the tension.

An eighteen-stringed Egyptian lyre will be found

preceding the pipes and harp, in the following from Wilkinson’s Egypt.

Singers, accompanied by Harp, Double Pipes, and Lyre.

ERATO’S UPRIGHT PSALTERY.

Psaltery was a general name for several kinds of

stringed instruments. The Greek word, psalterion,

is derived from psallein, to twang a

string with the fingers, as a bow-string. Every stringed instrument which was

played upon with the fingers of both hands, instead of by one hand and a

plectrum held in the other, came under the denomination of a psaltery.

Therefore the Greek name for a harp was also psalterion.

Again, the harp might be called a Trigon, in reference to one of triangular

shape. Aristotle combines the two words, Psalterion and Trigon, in defining our harp. On the other hand, Psalteries were not

necessarily Trigons, as will be seen from the following copy of a painting

found in Herculaneum.

The instrument is evidently the four-sided, or Upright

Psaltery. A second representation of one of the same description is also

included in the Herculaneum collection. It has a similar outline, and the same

number of strings; but the painter, who placed it in the hands of Achilles, and

represented him as taking his music-lesson from the Centaur Chiron, forgot, in

that case, that there was such a thing as a sounding-board necessary to give

sonority to the strings. However, to give the artist the benefit of the doubt,

he may have intended to represent Achilles as taking his music-lessons upon a

dumb instrument, in order that he might not offend Chiron’s ears.

In the following representation the Muse Erato holds a

ten-stringed psaltery; and, happily, both the name of the Muse, and that of the

instrument which she holds, are given at the foot, so as to remove any doubt.

Athenaeus’ distinction of an upright psaltery might

lead to the inference that there was another kind to be used in a horizontal

position. In such a case the employment of wire strings might be suspected, and

that, so far, it would resemble the modern dulcimer; but no sign of the

employment of such thin wire strings as would be required for this purpose has

yet been traced among the ancients; or, at least, no such discovery has

hitherto been made known. We have no proof that the art of wiredrawing was then

understood, and Athenaeus must therefore be supposed to distinguish between the

quadrilateral and the triangular psalteries.

In the Egyptian Sistrum there were loose bars of metal

to be rattled by shaking; and in the Assyrian dulcimer there were firm bars of

metal of different lengths, fixed into a frame by bending, and these were to be

struck by a short rod; but in no case have such thin wires yet been found as

could be tuned by turning them round a pin or a peg.

The Egyptian instruments made of metal rods, and fixed

either at one or at both ends, have already been referred to.

The psalteries of ancient Greece cannot have been

strung with wire, because no such instruments would have been played upon with

the hands. The ancient Greeks were very tender of their fingers, as may be seen

by their preference for a plectrum to touch even the finer catgut strings of

the lyre. Fingers were their purveyors for the mouth, and the forefinger of the

right hand was made especially useful in cleaning out the dish. The practice of

employing two hands was primarily due to a multiplication of strings, and that

increase was one of the many importations from Asia, or from Egypt. Clemens Alexandrinus says that Psalterion was a name applied generally to such stringed instruments as were Egyptian.

That would be on account of their larger number of notes requiring the use of

two hands. A plectrum was unfitted for playing chorda, it could only sound one

string at a time, or slip from one to the next.

Psalmos is another name for a Psaltery, and the only distinction that can now be

drawn between the two is, that Psalmos implies an

instrument made expressly for accompanying the voice, and that the same

designation includes any song to be chanted or sung with such an accompaniment.

Hence our word Psalm. Whoever may wish to return to the primitive use of

psalmody should therefore chant or sing the Psalms, whether he may adopt the

one version in prose, or the other in metre. The Psalmos must have had at least ten strings, if not more,

because Plutarch speaks of it as an octave-playing instrument. We might infer

from his description that the number was much larger, if he had not coupled

with it the Phorminx, in the same sentence. We know of no Greek lyre that had

more than fifteen strings, and even such a lyre would have been ranked as a Polychordon. On the other hand, we have, at p. 306, a

representation of an Egyptian lyre which has seventeen or eighteen strings.

THE EPIGONEION, WITH FORTY STRINGS.

We now arrive at a Greek instrument that must have

been originally the true Egyptian harp, but which was afterwards changed in

form, and mutilated in compass, by the Greeks. Julius Pollux says that the Epigoneion had forty strings, and that it took its name

from Epigonus, who was the first to introduce it. Athenaeus adds, upon the

authority of Jobas, or Juba, (the learned King of

Mauritania, who had been educated in Italy,) that Epigonus brought the

instrument from Alexandria, and that he played upon it with the fingers of both

hands, instead of the Greek usage of but one hand, and of employing a plectrum

with the other. Further, that Epigonus did not confine the powers of his harp

to a simple accompaniment for the voice, but introduced chromatic passages, and

instituted a chorus. Nevertheless, his example was not followed by the Greeks;

for Athenaeus adds that the Epigoneion had been

transformed into an upright psaltery, although it still retained the name of

the attributed inventor. So the ultimate meaning of the word was an instrument to be played upon with two hands, after the manner of

Epigonus.

Any portable instrument having forty strings would

necessarily be made of triangular form, on account of the extreme difference of

length that was absolutely required between the longest and the shortest

string. No other shape was practicable where the diminution was progressive,

and the number so large. The transformation of an instrument of forty strings

into one of only ten proves that the cultivation of music was not sufficiently

advanced among the Greek people, to enable them to appreciate such harmony as

arises from many simultaneous sounds. Every one who

can now listen with pleasure to the chords upon a harp or a pianoforte is in

advance of the average of musical intelligence among the ancient Greeks.

The Greeks had also a second kind of harp, called the Simikion, or Simikon. It had

thirty-five strings, but the reason for its name is unknown. All the musical

instruments of Egypt must have been known to the Greeks, and yet, as to those

which had many strings, we find scarcely a reference to one of them in the

works of Greek classical authors, or a representation in their sculptures. As

two Octaves are the full average compass of the human voice, so fifteen strings

seem to have been the maximum extent of Greek musical instruments. The Simikion, and the Epigoneion in

its original form, are rather to be classed among instruments once known to the

Greeks, than among Greek instruments.

The Romans undoubtedly approved the combination of

numerous instruments in concert, but rather, as it seems, for their increased

loudness, than from any more decided taste for harmony than that of the Greeks.

Indeed, both Greeks and Romans sink below the average, when compared either by

the standard of the most ancient, or of the modem stages of musical

cultivation. This is perfectly natural; for nations so often engaged in war,

and especially with intestine wars, could have but little leisure for the more intellectual

branches of art or science. The only inventions encouraged, at such times,, are

those of some new missile for destruction, while the arts of peace die away,,

rather than make advance. The history of music affords throughout the most

perfect proof of this acknowledged maxim.

STATE OF THE CULTIVATION OF MUSIC

In consequence of the absence of representations in

the sculptures and paintings of Greece and of Italy, we must revert to Egypt

for the forms of ancient harps, and there we may indeed find them portrayed to

perfection. Some [Egyptian] harps, says Sir Gardner Wilkinson, stood on the

ground while played, having an even, broad base; others were placed on a stool,

or raised upon a stand, or limb, attached to the lower part. Men and women

often used harps of the same compass, and even the smallest, of four strings,

were played by men; but the largest were mostly appropriated to the latter, who

stood during the performance. These large harps had a flat base, so as to stand

without a support, like those in Bruce’s Tomb; and a lighter kind was also

squared for the same purpose, but, when played, was frequently inclined towards

the performer, who supported the instrument in the most convenient position.

The Egyptian name for the harp was Bouni, having

usually the prefix of the article Ta, in the feminine gender for The.

The preceding highly ornamented harps are copied from

paintings in the Tomb of Rameses III, by Wilkinson, whose remarkable accuracy

has been so frequently attested by more recent travellers.

They are of the greater interest because they exhibit two of the stages of

transition from the original shape of a bow to that of a triangle. The one is

bent over like the stem of a pliable tree from its trunk, while the larger

number of strings upon the other necessitates a nearer degree of approach to

the triangular form.

When James Bruce, the celebrated Eastern traveller, first brought home the model of harps of this

kind from Thebes, because they had no poles; which were judged necessary to

support the forearm against the tension of the strings, his account was

disbelieved, and he was nick-named the Theban Lyre. Bruce’s truthfulness has

been vindicated by every succeeding traveller, and in

the most ample manner ; but the want of. poles to Egyptian harps has

nevertheless appeared as a singular deficiency in so advanced a stage of art.

On the other hand, it is a satisfactory proof that the bow and bow-string were

the models upon which these instruments were originally, formed; indeed, we may

see the earliest Egyptian harps to have been bow-shaped, as are those of the

fourth dynasty, exhibited at p. 65. The bow-shape did not admit of treble

strings, and hence the substitution of the triangle.

Many minor varieties of harp-form will be found in the

admirable work from which the last two splendid specimens have been borrowed.

In a general history, extracts are necessarily limited to essential varieties

in construction, and the Popular Account of the Ancient Egyptians is accessible

to all. More is to be learnt about the inner life of the Egyptians from Sir J.

Gardner Wilkinson’s volumes than from the costly and noble works of Lepsius,

Rosellini, and others put together. A great lesson is also to be derived as to

the rise and fall of nations, and how art, science, and literature, spring up

and decline with them. In Sir Gardner Wilkinson’s pages we see the character of

the Egyptians: a great and free people under then-own kings, learned, skilful,

inventive, industrious, sportive, and mirthful; also more humane, because more

civilized, than any other ancient nation. The Egyptians make no exhibitions of

torturing prisoners and flaying them alive, as do the Assyrians, the Egyptians had no gladiatorial fights, like the Romans, human sacrifices had been abolished in the empire of Upper Egypt for ages

before Moses was born. Dr. Burney says that the Greeks and Romans made religion

an object of joy and festivity, but that the Egyptians worshipped their gods

with sorrow and tears. He made this erroneous deduction from a corrupt text of

Ammianus Marcellinus, written after the nation had been crushed by five hundred

years of slavery. It should be: The Egyptians have a suppliant, rather than a sad,

expression of face, and not, they are even more sad. How

different is sadness to the song and dance to Ptah, or Vulcan, exhibited at p.

63. Women, we know, are more readily given to tears than men, but even the

ladies are there sufficiently happy-looking and cheerful. So late as the end of

the first century of our era, Dion Chrysostom speaks of the Egyptians as

cheerful and hilarious, although they had a mortal objection to paying tribute.

The men had also the credit, a little before that date, of having become expert

thieves. The crushing out of such a nation is one of the problems of the world.

Josephus, in his answer to Apion, triumphantly

accounts for it on the score that the Egyptians were never admitted to

citizenship by any of their conquerors. This policy was often reversed in the

case of smaller nations, like the Jews, who were less to be dreaded. Whatever

may have been the causes, or cause, the Copts, who are but a mixed race, seem

now to be the only remaining descendants of the once mighty nation of the

Egyptians.

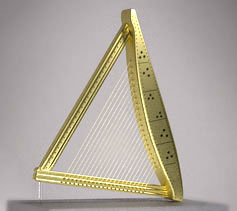

Egyptian triangular harps, or Trigons, had but a frame

on two sides of the triangle, the third side being formed by the lowest string,

but the Etruscan had frames complete. A fine example of these will be exhibited

in the sequel, under the head of Hebrew Music. They are of the class so much

referred to in the middle ages as in the form of the Greek letter delta,

and, therefore, as emblematic of the Trinity. The same form is found in

Herculaneum.

TRIGON, OR TRIANGULAR HARP

The Egyptians had triangular harps in great varieties

of form. The following is one of twenty one strings, and the original

instrument is included in the Paris collection.

An imaginary Egyptian Trigon will be found in Wilkinson’s

Egypt, and in Champollion’s great work, under the arm of Typhon. In depicting

the gods, such license might well be allowed, but some sculptors employed their

imagination equally upon musical instruments which they put in the hands of

mortals. The Assyrian sculptor, who designed the triumphal procession on the

magnificent marble slab, which represents the triumph of their king

Asshur-Bani-Pal over the Susians, and which is now in

the British Museum, has indulged his fancy rather overmuch in the forms of the

harps which the harpers are supposed, to be playing in the open air, at this

celebration. The instruments have no other sounding-boards than one upper bar,

and the lower is too weak to bear the requisite tension. They consist of one

horizontal and one nearly vertical bar, therefore approaching to a right angle,

without support to the comer at which they are joined. If of metal, the harps

would give no sound, and if of wood, the strings could not be tuned to an

audible pitch without breaking the frame. There are instruments of similar

character in Egypt, but the bars and the strings are shorter. We must suppose

that, in both cases, one of the bars was large enough to be made hollow, so as

to assist the production of tone.

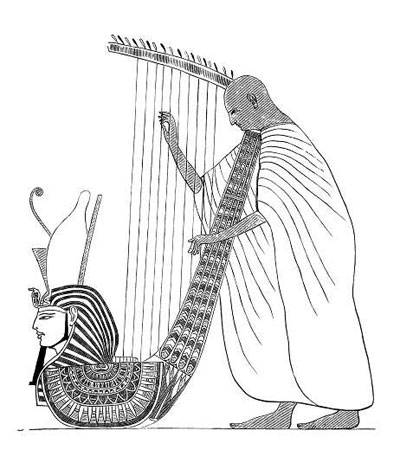

The following elegantly designed harp, in the hands of

a blind man, is of smaller size than those in Bruce’s Tomb. We have here a band

of blind men, with harp, double pipes, and lute, or Nefer. The last named

instrument has a head, either of a god or of a human being, carved at the

extremity; and it may be noted that the old English cittern inherited this

characteristic. Music has been a resource for the blind of civilized countries

in all ages. In England and Wales blind harpers, who sang ballads to their

harps, were once as numerous as are blind organists now. The frequent

representations of Egyptian blind men playing or singing in concert prove a

system of musical education for the blind in ancient Egypt. The preceding

representation is taken from Lepsius’s great work, and a second, very much like

it, will be found in Wilkinson’s Popular Account, vol. I. p. 110. The harp has

not there quite so many strings, and the central figure is beating time,

instead of playing on the pipes.

ROMAN FOUR-STRINGED TRIGONS.

Small Trigons, or harps with only four strings, seem

to have been used by Roman singers for the sole purpose of taking a pitch for

the voice. If tuned to an Octave chord, they would have had one outer string

double the length of the other. Horace refers to them in the third Satire of

his first book. The subject of the Satire is a celebrated musician, named Tigellius, who was admitted to intimacy by C. Julius

Caesar. The first eight lines of the argument may be stated as follows: Singers

have all one failing that they cannot bring themselves to sing to their

friends when they are asked, but when unasked they never leave off. This was

the case with the Sardinian Tigellius. Even Caesar

himself, though he were to entreat him by his father’s friendship, and by his

own, could not prevail upon him to sing; but, if Tigellius were in the humour, he would sing convivial songs

from the time of egg to that of the apples, or from the beginning to the end of

the repast. Then follows the musical point

.........modo summa

Voce, modo hac resonat quae chordis quatuor ima,

at one time in the highest pitch of his voice, and at another, in that

[pitch] which vibrates lowest in the four strings; or less literally, at the

pitch of the lowest of the four.

A doubt has long been felt by the learned as to

whether summa voce is to be taken to denote highest pitch in our sense,

or lowest pitch in the Greek musical application of the word Hypate. I submit that the evidence of Nicomachus clears up the doubt, and that the former is the true rendering. I have already

shown from his treatise, that Hypate was the name of a string, or strings, upon the lyre, and had no

reference to the sound produced by those strings. It or they were simply highest

by being the longest upon the lyre. So the sense of Nete and of Hypate was

not changed in music. The mistake was to think of them as to the notes they

produced instead of as mere strings.

THE DEFICIENCIES OF BOETHIUS.

The confusion as to the meaning of the two words seems

to have originated with Boethius, and is therefore of very long standing. I

observed his error while skimming over his treatise after the principles of

Greek music had been fixed in my mind. I noted also that the forte of

Boethius rests in arithmetic of the oldest school of musical proportions, and

that the remainder of his treatise is but indiscriminately copied from Greek

writers, without a thorough understanding of the subject. The one inducement to

him to write upon music must have been the arithmetical part, so as to form a

sequel to his De Institutione Arithmetica. He limits his definition of the science of

music to the cognitio rationis,

and declares it to be as superior to the practical branch as the mind is to the

body. This is only an apology for his want of practical knowledge, and

his cognitio rationis should

be translated, acquiring a knowledge of the ratios of intervals, for that is

the limit of his acquaintance with the science. Boethius makes such a confusion

of terms between summa and ima,

in reference to Hypate and Nete,

and so turns the Greek scale upside down, that I can only transfer the passages

to a note. It is strange that he should quote the very paragraph from Nicomachus, comparing the seven planets to seven strings of

the lyre, and yet not discover the meaning of Nete and

of Hypate. His treatise, which has now

been regarded as a grand authority for many ages, has really been the prime

cause that the subject of ancient music has been so generally misunderstood.

ORGANS

|