THE HISTORY OF MUSIC (art and Science) FROM THE EARLIEST RECORDS TO THE FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

CHAPTER

XIII

ORGANS

Organs of two kinds were known to the ancients. One

was the Pneumatic Organ, which was blown by bellows fashioned very much in the

present style, and the second was popularly called the Hydraulic Organ (in

Greek, Hydraulis, or Hydraulikon Organon). In spite of its name, this second instrument was decidedly not

hydraulic, although it bore the appearance of being so.

The Hydraulic Organ was always an enigma to

superficial observers. They saw water bubbling up from the bottom of an open

vessel, and the water in the perpetual interchange of rise and fall, and of

rolling or tumbling about. They saw a piston working in a cylinder, and at

every stroke of the piston the water rose higher in the vessel. Hence they

concluded, naturally enough, that it was water which was undergoing the process

of injection into the pipes of this organ, and that the effects were produced

by means of that syringe-like pump. But it was simply a condensing syringe

acting upon air.

Ctesibius, the Egyptian, was the inventor, and the date of this one of the several

inventions attributed to him may be fixed within the reign of Ptolemy

Philadelphus, or between the years 284 and 246 B.C. The question may one day

arise as to whether all these were the inventions of Ctesibius,

or whether he was but the medium of communicating Egyptian science to the

Greeks.

The biographer of Philon, the cele6brated mechanician

of Byzantium, in Dr. W. Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, has relied upon a statement by Athenaeus, that Ctesibius flourished in the reign of Ptolemy Euergetes II. He

has therefore dated three important men in the history of science a full

century or more too near to our own times, viz., Ctesibius,

Philon, and Heron of Alexandria. Athenaeus was undoubtedly mistaken when he

wrote Euergetes II. It should have been Euergetes I; but, as he was recounting an historical event

of five hundred years before his own time, Athenaeus was liable to such slips. Euergetes I succeeded Ptolemy Philadelphus, but the

invention of the organ must be referred to the earlier of the two reigns.

An epigram, by Hedylus,

fixes the date conclusively, and a copy of this epigram is included in Athenaeus’s

own book. He must therefore have forgotten it when he wrote Euergetes II. Hedylus therein alludes to the temple of Arsinoe,

to the Hydraulic Organ, and to Ctesibius as its

inventor. This Hedylus was the rival of Callimachus,

who was librarian to Ptolemy Philadelphus, or Ptolemy II. Upon the authority of Hedylus, or even upon that of the epigram alone,

without the name of its author, there can be no reasonable doubt as to the date

of Ctesibius. No one would be found to pay homage to

the deceased Arsinoe, as to a divinity, after her brother-husband’s death.

VARIOUS MEANINGS OF ORGAN.

There is often a difficulty as to the precise meaning

of the word organ in Greek and in Latin, when it is unaccompanied by further

explanation. Any simple mechanical invention, musical or otherwise, was an

organ. Ordinarily, the best translation is the first of those given by Liddell

and Scott, an instrument; for it might be a surgical instrument; or it might be

a musical instrument, such as a simple pipe; or even an organ of sense, as the instrument of reasoning, or of

other power. Vitruvius draws a distinction between an organ and a machine, as

that a machine requires the labour of several

persons, or a greater exertion of power by one than is required for an organ;

whereas all the powers of an organ may be exhibited, without any especial

exertion, by one alone. It is not, therefore, to be inferred, as it has been by

some musical writers, that a Greek organon, or a Latin organum,

must necessarily mean a musical instrument; but rather that every manufactured

musical instrument might be included under the designation

of organon.

The first full description of the Hydraulic Organ is

by Heron of Alexandria, who was a pupil of its inventor, Ctesibius. Ctesibius seems to have flourished only some fifty

years after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great; and, not only in that

century, but even long after it, all who desired to obtain a thorough knowledge

of art or science, such as no European teachers could impart, sought to place

themselves under Egyptian masters. Philon, the mechanician of Byzantium, the

site of Constantinople, must also have been to some extent, if not altogether,

a pupil of Ctesibius. In his Belopoiika he

speaks of Ctesibius in the past tense, as having

resided in Alexandria, and of his having explained to him the nature of air,

and especially its elasticity. He refers also to several inventions by Ctesibius, and, among them, to the Hydraulic Organ. Philon

defines it as a kind of syrinx played by the hands, which we call hydraulis; and he adds, that the kind of bellows, by

which the pnigeus, or air-condenser, was filled with

air, was made of copper. It was, in fact, nothing more than a condensing

syringe, which is just the opposite of the modern air-pump, or exhausting

syringe; for the first pumps air into a receiver, and the second withdraws the

air. The Egyptians had for ages before employed small syringes for injecting

embalming fluids into the bodies of the dead.

The second full description of the Hydraulic Organ is

by Vitruvius Pollio, in his discursive treatise upon Architecture. The date of

this treatise is stated to be between B.C. 20 and 11. Although there have been

numberless commentators upon the works of Heron and of Vitruvius, the Hydraulic

Organ has not been sufficiently explained, and does not seem even now to be

fully understood.

I argue thus, from still reading Athenaeus’s erroneous

description quoted by an eminent scholar, in one of the latest English books.

Thus, currency is given to the fable of the pipes having been bent down into

water, and the water being pounded by an

attendant. From this it is evident that the mistake of Athenaeus has not yet

been satisfactorily proved.

Athenaeus knew nothing except by hearsay about the

Hydraulic Organ, for he goes so far as to assert that it was debated whether it

ought to be classed among wind or stringed instruments. If he had understood

its construction, he would have ridiculed such a discussion.

Neither Sir John Hawkins nor Dr. Burney, our two recognised musical historians, has rendered any assistance

towards correcting the error of Athenaeus they give up the instrument as incomprehensible. Neither does the Hydraulic

Organ seem to be better understood in Germany than in England, if an opinion

may be formed from the labours of one of the latest

exponents of the musical instruments of the ancients. In a work of such a

class, some special study of the subject might reasonably be expected, but Herr

Volkmann informs his readers that the pipes of the organ were filled with air

through the compression of water enclosed in a bronze receiver, which water

boys were stirring about. Also, that the organ was played upon with difficulty,

and with considerable exertion. As to the difficulty of performing upon the

instrument, Herr Volkmann seems to have mistaken the labours of the bellows-blower for those of the organist. The organ itself was of very

light touch, and the labour of filling it with air

fell upon the attendants. As to the compression of water, the learned writer

must be understood to mean compression of air by water, which is not over-clearly expressed. The boys did but pump in air; and the

air was enclosed under a receiver, into which water had free ingress and

egress. Water is practically incompressible.

I shall have occasion to explain the principle of the

instrument hereafter, and will now only adduce the evidence of Claudian, as an

eye-witness to the lightness of the touch.

In one of his poems, Claudian lauds the organist as “He

who, sending forth powerful rolling sounds by his light touch, can cause the

countless tones, which spring from the graduated multitude of bronze pipes, to

resound to his wandering finger; and who, by a beam-like lever, can arouse from

their depths the struggling waters into song”.

These lines are thus versified by Dr. Busby:

With flying fingers, as they lightsome bound,

From brazen tubes he draws the pealing sound.

LIGHT TOUCH OF THE ORGAN.

Unnumbered notes the captive ear surprise,

And swell the thunder, as his art he plies :

The beamy bar is heaved! the waters wake!

And liquid lapses liquid music make.

Claudian refers to one of the large Roman organs

dating from the second to the fourth century of our era, and not to those which

existed two or three centuries before the commencement of that era. The pipes

of the earliest organs were made of large reeds, just as are those of the

Chinese at the present time, and not, at first, of bronze. But, from Claudian’s description, it appears that the touch of the

large Roman organs was equally light; and, indeed, there is no reason that it

should have been otherwise, for the key-action of the one must have answered

equally well for the other.

One of the ablest commentators upon the Hydraulic

Organ, in modern times, is Isaac Vossius, in

his De Poematum Cantu, et viribus Rhythmi, printed at Oxford in 1673. In this work

he gives a partial description of the organ of Vitruvius, and supplies many of

the quotations which have since been constantly reappearing in the works of

later commentators. During the eighteenth century, perhaps the ablest treatise

on the subject was that of Albert Meister, in 1771. It is mainly copied from Vossius. Gottlob Schneider, in his careful edition of

Vitruvius, supplied much that was desired towards a correct text of his author,

but he does not explain the principle of the organ.

The comments of Vossius, of

Albert Meister, and many others, were published before the Histories of Burney

and of Hawkins. Dr. Burney, remarking upon them, says: But neither the

description of the Hydraulic Organ in Vitruvius, nor the conjectures of his

innumerable commentators, have put it into the power of the modems either to

imitate or perfectly to conceive the manner of its construction. And Sir John

Hawkins says: So imperfectly has Vitruvius described it, that to understand his

meaning has given infinite trouble and vexation to many a learned commentator.

And again, after publishing the Latin text of Vitruvius, from a copy not

over-carefully collated, Hawkins adds: This description to every modern reader

must appear unintelligible.

I cannot admit the existence of any such extraordinary

difficulties. The descriptions are troublesome, as I found when scrutinizing

that of Heron; but it sufficed for me, after some reflection, to make an

experimental Hydraulic Organ, and it answers perfectly. That which is now more

wanted than a new translation is an explanation of the principle of the

instrument, and I do not doubt but that I can make it intelligible henceforth

to everyone who may indulge a wish to understand it. A mass of learning has hitherto

been expended upon it without any very adequate result.

PRINCIPLE OF THE HYDRAULIC ORGAN.

If only a thoroughly good translation of Heron were

wanted, there could not be, so far as I am able to judge, a better than the one

included in the English edition of Heron’s Pneumatika, or Spiritalia, published in 1851.

The translation is by Mr. J. G. Greenwood, Fellow of University College,

London. Manuscripts must have been carefully collated for the text of that

edition.

The principle of the Hydraulic Organ is both simple

and ingenious, but it is one no longer in use. To this fact we may trace, at

least, one reason why it has not hitherto been generally understood.

I have already said that the name hydraulic is, at

least in the modern view, incorrect. There is not one water-pipe in the

instrument they are all for air. The Greeks were not far advanced in science when the

public gave it this name. The earliest description is in a Greek work on

Pneumatics.

The ingenious application of water was but to prevent

the possibility of over-blowing the instrument, and thus to save it from the

destruction to which the Pneumatic Organ was always liable from that particular

cause. Such an improvement was, no doubt, the principal reason for the superior

popularity of the Hydraulic over the Pneumatic Organ for many centuries. A

second advantage in the Hydraulic Organ was, that the condensing syringe for

injecting air took up less space than the Egyptian-shaped bellows, which were

trodden by the feet, and which the sculptured Pneumatic Organs on the Obelisk

of Theodosius prove to have been continued in use by the Romans down to the

fourth century of our era.

The apparatus for supplying wind to the Hydraulic

Organ acted vertically, and not horizontally, as it would in bellows. The

upright condensing syringe was worked by a lever from below. It pumped in wind,

but no water. It injected air very spasmodically, on account of the elasticity

of air, and as a syringe it could act only at intermittent intervals. The

distribution of the air was then equalized, and the supply to the pipes was

maintained by the pressure of water returning to seek its level under the bronze

receiver, from which it had been previously expelled by the air. The receiver

was open at the bottom, and, according to Vitruvius, its edges were supported

by wedges. Thus the water had free ingress and egress. It is a well-known fact

that the pressure of water is alike in all directions, so that it must act

equally well upwards or downwards.

The law is that liquids transmit pressure equally in

all directions, and the pressure they produce by their own weight is

proportionate to the depth.

And now, for exemplification, take a glass funnel, and

turn the broad end downwards in a pan of water. Put a cork under the funnel,

and it will float upon the surface of the water. If you then cover the smaller

end of the funnel with your lips and blow down it, you will see the cork sink

gradually to the bottom of the pan. When it has arrived there, all the water

will have been expelled from under the funnel, and, instead of water, it will

be filled by the breath from your mouth. The water which you have driven out

will necessarily mix with, and raise the height of the outer water, which is

around the funnel, in the pan. If you then continue to blow, your breath will

only rise in bubbles from the bottom of the pan to the surface of the water.

The elastic force of the increased quantity of air within the funnel has become

too great to be further condensed by that insufficient weight of water.

Now, suddenly remove your lips, and put a tiny organ

pipe, or whistle, into the neck of the funnel, covering the pipe round with india rubber, or a cork, to make it fit into the neck. As

the pressure from your mouth is now withdrawn, and there is a hole through the

pipe which permits the escape of the air, the water will return, and in

returning under the funnel to seek its level, it will drive up the air that has

been enclosed, through the pipe. In doing this it will keep up a continuous

sound from the pipe just as if it were blown from the lips. The pressure of the

water will continue until it has found its level within as without. The water

exercises the pressure of its weight upon the air, and the higher the water in

the pan, the greater will be that weight. There is hardly a limit to the

compressibility and to the elasticity of air, (as witnessed in the pop-gun, and

in the air-gun,) but water is not practically compressible, and therefore is

not elastic. It exercises only its weight.

This is the simple secret of the pnigeus or air-compressor of the Hydraulic Organ. It is evident from it that the

Egyptian inventor understood the compressibility and the elastic power of air,

as well as that the pressure of water is equal in all directions.

We may note also an advantage in this system of

causing water to return to seek its own level under a solid open receiver. It

thus becomes a more powerful agent than if the same amount of water were

equally distributed as a weight upon the top of a drum-shaped, receiver having

elastic sides, because the water expelled from the pnigeus will raise the height of that in the pan or outer vessel, and the weight of

water is proportionate to its depth.

But the pnigeus, or

air-compressor of the organ, had two pipes at the top instead of the one of the

funnel, and being made of bronze instead of glass, it was impossible to see

into it, as through the glass of the funnel. Suppose, then, that instead of a

funnel, you use as an air-condenser a large pewter basin, inverted in a pan of

water, and, near to the circular rim, which would support the basin if it were

upright, let there be two holes on opposite sides. The first hole is for the

insertion of a pliable tube to communicate with the syringe by which the air is

to be injected into this condenser, and the second hole is for a somewhat

smaller tube, to carry air from this condenser into the organ. If the wind be

then injected into the condenser, it cannot escape through the second tube until

a key of the organ has been put down, to allow it to pass, and, in passing, to

sound a pipe. The only means of knowing whether this condensing receiver is

well supplied with air, is to continue blowing until bubbles rise from the

bottom of the pan to the surface of the water. Then as much air is inclosed as the pressure of the water will retain. If

greater loudness be required from the pipes, it is only necessary to take a

deeper, receiver, and to add more water in order to increase the weight upon

the enclosed air. Under any circumstances, the only way to make sure of having

a supply of air in readiness is to see the bubbles rise outwards.

If the pewter basin were deeper, and it were made of

copper or bronze, as was the Greek pnigeus which was used for this purpose, it would resemble a caldron, and the bubbling

up of the water from the bottom would, to a superficial observer, strengthen

the idea that it was really a caldron, and that the water was boiling.

To that appearance we may attribute the Latin name

of cortina (the caldron), given to

the Hydraulic Organ, as, for instance, in the poem of Aetna, of which a superior text has recently been edited,

from a Cambridge manuscript, by Mr. H. A. J. Munro, late Professor of Latin in

that University.

In the sequel of this book, if it should extend to the

Middle Ages, more allusions will be found to the supposed boiling of the water,

to make the pipes sound; one, even of as late a date as the twelfth century, in

the writings of William of Malmesbury.

It should be added that this pnigeus,

or air-condenser, was placed within a pedestal, made in the form of a small

altar, being either rounded and like a very short column, or hexagonal with its

base in steps. The tops of altars were hollowed out, to prevent the spread of

fire, and the pnigeus was a sort of extinguisher for

it. The water in the outer rim or basin of the condenser was kept incessantly

tossing up and down, because it rose at every fresh injection of air into the

condenser, and it fell again at every emission of that air through the smaller

tube into the organ, whenever the organist touched a key. This accounts for the

toiling and labouring of the water so often referred,

to, as by Tertullian and others.

The foregoing full explanation of the air-condenser,

air-compresser, or pnigeus,

has perhaps been demanded, because this contrivance of ancient science is no

longer in use, but the condensing syringe, which supplied the place of the

ordinary bellows, acted so much like an ordinary condensing syringe of today,

that, except perhaps as to the position of the valve, it will be better

understood by a glance at a diagram, than, from any number of words.

The question then arises as to which of the diagrams

is to be offered to the reader. It cannot be one copied from the small antique

designs upon medals or gems, because they are too minute to supply the details.

It may be desirable to reproduce one further on, not only for the sake of the

true external appearance of the Hydraulic Organ, but also for the purpose of

presenting to the enquiring public a portrait of one of the laurelled organists

of former days. Still, for present use, some one of the medieval designs must

be adopted, such as are found in manuscripts, or in early printed copies

of-Heron’s Pneumatika.

An objection may be raised to the one in Vetera Mathematica, and in other editions of

Heron’s work, on the following grounds. Either the artist, or the engraver, has

so rounded off the ends of tubes, and the mouths of cylinders, in order to

improve the picture according to his ideas of the beautiful, and yet, so little

in accordance with the description in the text, that, instead of elucidating,

they only tend to mystify the subject. The worthy man saw that the organ was

infinitely larger than the air-compressor, and therefore he gave it a tube four

times the size of the other; and yet, in practice, the intermittent action of

the condensing-syringe would require a channel double the size of the second

tube, which had to convey a continuous and equal flow of air into the organ.

Again, he has given a pretty battledore-shaped slide under the mouth of the

organ pipe, instead of a straight one. It has at least the merit of being large

enough, but how it was to slide in a narrow groove must be a mystery to all

enquirers.

Choice is embarrassing, for each artist has had his

special proclivities. I have adopted the diagram in the Harleian manuscript,

No. 5605, and, ceteris paribus, I was perhaps a little influenced

in the choice by a curious exhibition of idiosyncrasy on the part of the good

monk who must be supposed to have designed it. It appears that he could not

induce his pious fingers to draw a heathen altar as a support for anything, and

therefore he left the pnigeus dangling in the air.

Our less scrupulous artist has supplied the stand, but the reader must not

expect to find anything of the kind in the manuscript.

No one of these diagrams is of any authority, the

oldest extant copy of the Pneumatikanot being older than the fourteenth or fifteenth century. The text is the one and

only reliable source for elucidation.

It may be well to note that the condensing syringe, or

wind pump, must be understood as being detached from the organ; for, in this

design, it looks very much as if it were under it; moreover, the condensing

syringe, or wind-pump, as here represented, is of most unnecessary grandeur for

so small an air-compressor, or pnigeus.

Instead of the tedious series of three or four

letters, one for every angle of each part to be described, I have substituted

the names, which seem to be quite sufficient for an intelligent reader. The

lever by which the condensing syringe, or wind-pump, is worked explains itself.

The little valve to admit air is at the top of the syringe, in the small box

above the shoulder of the larger cylinder in which the piston works. It falls

to a restricted distance by its own weight when the piston is down, and so it

admits air; and it is closed by the rush of air from below when the piston is

suddenly forced upwards. That valve added greatly to the labour of blowing. The most important of subsequent improvements in the Hydraulic

Organ was in the form and character of the valve. Instead of being flat, as

here, it was made like a cymbal, or of a bell-shape, so as to catch the wind

from below more readily. Again, its weight was balanced from the outside, by

hanging this bell-shaped valve to a little chain, which was held in the mouth

of a dolphin shaped balance. The dolphin moved upon a centre-pin,

and his head went down or up with the bell. So he took off the weight of the

valve, and looked like a dolphin sporting. Thus, too, the popular idea of the

agency of water was further promoted.

And now as to the key-action of the organ. The diagram

is here enlarged in order to show more plainly the little key with three bent

arm. It will be seen that, when the key is pressed down at its upper extremity

by the finger, it will cause the lid of the box to slide on, so as to close it,

and thus to bring the little round hole in the lid under the mouth of the pipe,

and admit air to it. The box ought to have been inverted, the mouth of the pipe

fitted into it, and the slide should act below, instead of above, but then the

action could not have been seen.

The box should also have been exceedingly shallow, so

as only to take in hautboy reeds, and the lid to slide as in a box for dominos.

The shallower the box, the quicker would the pipe speak. The slide is the one

important part, and that alone is spoken of by later writers. The wind-chest of

the organ included an air-channel under these slides.

Wien the finger was raised from the key, there was a

piece of string, like the tape in a modern pianoforte action, to bring back the

key into its place. The string was attached to a spring secured to the case,

and this spring was made of elastic horn. It will be seen in the diagram acting

upon the lower end of the vertical arm of the key. The action is very simple.

The key turns upon a centre-pin, like two spokes of a

wheel upon its axle.

It has been argued that the Greeks had no keys to

their organs, because such a word as kleis,

which would express the key to a fastening or lock, is not named in connection

with musical instruments. But it should be remembered that we employ the

English word idiomatically. Even in Latin, Vitruvius uses pinna for an

organ-key for playing upon the instrument, and would only adopt such a word

as clavis for a key in the literal

sense, if it were to lock up the instrument.

The hydraulic action of modem organs does not bear any

resemblance to the ancient. The object of the present hydraulic action is only

to diminish the weight of the touch.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE HYDRAULIC ORGAN.

The following is the invention of Ctesibius,

as described by Heron of Alexandria. I give a free translation, because it will

save trouble to all readers. For instance, a word like kanon is

here used in half-a-dozen different senses. Any straight rod, beam, pole, or

rule of any kind is a kanon, besides its

other meanings. Here, it is at one time a piston-rod; next, the beam of a

lever; thirdly, the fulcrum upon which the lever works; fourthly, it is a part

of the case within the organ. To give at once its precise name saves the reader

the trouble of gathering from the description what kind of kanon is there intended. The most tiresome part

of all indefinite or technical descriptions is the summing up of an author’s

words to find out his meaning.

Herons’ Pneumatika, or Spiritalia, has not been

reprinted in Greek for the last two centuries, therefore, that part of the work

which contains the description of the Hydraulic Organ is now freed from

abbreviations, and subjoined in modern types. The only exception is, as to the

three letters, koppa, sampi,

and stigma, which are only here employed to denote parts of the

instrument, and therefore do not give any trouble :

Let there be a small altar-like pedestal of bronze,

containing water. In the water let there be a convex hemisphere, called a pnigeus, retaining a free passage for water underneath it.

From and through the top of this pnigeus, let two

tubes be carried above the pedestal; one of them bending downwards outside the

pedestal, and communicating with the box of a condensing syringe having its

mouth downwards, and its inner surface made smooth and true to fit a piston.

Let the piston be well fitted into this box, or cylinder, so that no air may

escape by its side, and to the piston attach a very strong piston-rod. Again,

to this piston-rod attach a transverse rod, which shall act as a centre-pin (at v), and work as a lever upon an upright

fulcrum which must be firmly set.

Into the inverted bottom of the box above described

insert another box of small size, with its mouth quite open to the larger, but

closed above, and having a hole through the upper part, by which air may enter

into the larger box. But under this hole let there be a thin plate to close it,

and let this plate be upheld by pins passing through small holes made in it,

and these pins are to have heads, so that the plate may not fall off. Such a

plate is called a valve (platusmation).

The second tube from the top of the pnigeus is to be carried up to communicate with the

transverse channel [included in the wind-chest of the organ]. Into this

transverse channel the ends of the organ pipes are inserted, and have their

extremities enclosed in little boxes, such as are made to hold hautboy reeds.

The orifices of the organ pipes are left open within them.

The lids of these boxes are to slide over the orifices

of the organ pipes, and they must have holes made in them, so that when the

sliding lids are pushed home, the holes in them may correspond with the

orifices of the organ pipes; but when the sliding lids are drawn back, they

will pass over these orifices and close the pipes.

Now, if the lever be depressed at its extremity the

piston will be raised, and thus expel the air which is enclosed in the box of

the cylinder, and the force of that air will close the hole in the little box

above it, through its action upon the aforesaid valve. The air can then pass

out only through the first tube, and so into the pnigeus;

again, out of the pnigeus, along the second tube,

into the wind-chest of the organ; lastly, out of the wind-chest of the organ

into the pipes, if the orifices in the pipes and the holes in the sliding lids

coincide and that is, when the lids, or some of them, are pushed home.

Therefore, in

order that, when we wish any of the pipes to sound, their orifices may be open,

and that, when we wish them to cease, these orifices may be shut, we may do as

follows:

[The Action of the Key.] Suppose one of the reed-boxes to be separated from the rest, the open part

of its sliding lid being δ; the organ pipe above it being ε; the entire slide that fits below the organ pipe being ςρ; and the hole in that slide which is to correspond with the orifice of the

organ pipe being η. Then let

there be a key with three little bent arms to it, of which the arm is attached

to the above-named slide, and the key to turn upon a centre-pin

at μ2.

If we depress with the hand the highest arm of the key

in the direction of the open part of the slide (δ), we shall push the slide inwards, and when it has reached the end of the

box, the hole in the lid will correspond with the orifice of the organ pipe.

In order that, when we withdraw the hand, the slide

may also be withdrawn mechanically, and thus close the communication with the

pipe, do as follows:

Rather lower than the reed-boxes, but at the level of,

and parallel to, the wind-chest, let a rod (υ4 υ6) be

carried along, and to this rod fix slips of horn, elastic and curved, one of

which (υ6) is

opposite to the reed-box (δγ).

From the top of this piece of horn let a catgut

string, well secured to it, be carried round the extremity of the key (θ), [the point of the lower angle of the key,] so that, when the sliding lid

is pushed in the opposite direction, the string may be tightened. Then, if we

depress the upper part of the key at its extremity (υ2), we drive home the lid of the box, and the string draws after it the end

of the piece of horn, so as to straighten it by this traction.

But when the hand is withdrawn from the key, the horn,

by returning to its original form, draws back the slide away from the mouth of

its box, so as to overlap and cover up the hole in the end of the organ pipe.

A contrivance of this kind being applied to the

box under each of the pipes, when we wish some of the pipes to sound, we must

press with the fingers the key of each; and when we do not wish them to sound,

we withdraw the fingers, and then the pipes from which the slides are drawn

away will cease to sound.

[The Principle of the Instrument.] Water is poured into the stand in order that the superabundant air, I mean that which, when driven out of the cylinder, raises the height of

the water in the stand may be

retained within the pnigeus, so that the pipes shall

always have a supply in readiness to enable them to be sounded.

When the piston (ρσ) is raised, it drives the air out of the cylinder, as already explained,

into the pnigeus; and when the piston is depressed,

it opens the valve in the little box above it, by which means the cylinder is

refilled with air from without. So that, when the piston is again forced up, it

will again drive air into the pnigeus.

It is better that the piston-rod (τυ) should work round a centre-pin at τ [where it joins the lever], and this by means of a ring in the bottom of

the piston-rod, through which the centre-pin [formed

by the end of the lever-rod] must pass, in order that the piston may not be

twisted, but rise and fall vertically.

Between the age of Heron and that of Vitruvius, there

is not perhaps any extant notice of the Hydraulic Organ which will throw

additional light upon its construction. The description of Vitruvius is ample

for those who have some previous knowledge of the instrument; but it has the

fault of being too briefly expressed to be intelligible to others who have not

had that experience. It is evident, from the concluding passage of his chapter,

that Vitruvius did not anticipate any better result from his labours. At least four attempts have been made to translate

his work into English, but all have failed at this point. The last two are by

Newton and Gwilt. Newton leaves the hard words as they stand in the original,

trusting that their meanings may be discovered by the reader. He writes of the little

cistern which supports the head of the machine, instead of the wind-chest of

the organ, and of brass buckets with movable pistons. The late Joseph Gwilt,

who was learned in music of the Madrigalian era, has

nevertheless misconceived the Hydraulic Organ. He translates manubreis ferreis with

iron finger-boards, (instead of with iron handles,) although, in the next line,

these handles are to be turned round.

For these reasons, the first object of a new attempt

should be to write so explicitly as to make it possible that every one may

understand. I therefore amplify the description of Vitruvius, and appeal rather

to his words, to justify the construction I have put upon them, than offer such

a literal translation as may hereafter be made by any one, with the assistance

of the paraphrase. The sentences of Vitruvius are exceedingly long and

interwoven, and I have therefore divided them into parts. Further than this Vitruvius having two condensing syringes, or wind-pumps, to his organ

instead of one, describes each part of them in the plural number. He thus

complicates his explanations ; but as the two are alike, it suffices to

describe one, and to reserve plurals for parts of that one.

The accompanying diagram is mainly a copy from one

made by Isaac Vossius for his De Poematum Cantu et Viribus Rhythmi. Vossius’s dolphins

are made to work by the tail instead of by the bead, because the text that he

followed had ex oere, instead

of ex ore. He therefore referred those words to the cymbals; but as

cymbals were invariably of metal, the addition of ex oere would have been superfluous. Isaac Vossius understood the instrument, but as he was treating

upon another subject, he did not complete his explanation. Again, he wrote in

Latin, like Vitruvius, and so he left some technical difficulties which neither

Dr. Burney nor Sir John Hawkins1 could master.

THE HYDRAULIC ORGAN DESCRIBED BY VITRUVIUS.

But I will not omit to touch, as briefly as possible,

upon the plan of the Hydraulic Organ, and to express, as well as I can in

writing, the principle of its construction.

A bronze altar-shaped pedestal is set upon a basis of

timber.

Upon this same basis are straight bars of wood, shaped

like the sides of ladders, and erected both on the right and on the left of the

pedestal. The bronze cylinders of two condensing syringes, (one on each side,)

are maintained in an erect position by these bars. Each of these cylinders has

a movable piston, which has been carefully turned by the lathe. The piston has

an iron elbow-joint fixed into its centre [at the

lower end]. The vertical arm of this elbow is formed by the piston-rod; and the

horizontal arm by a lever, the end of which passes through the handle of the

piston-rod, and thus becomes the centre-pin by which

the piston-rod is raised or depressed. It is covered with unshorn sheepskin [to

prevent noisy action].

In the top of each of the cylinders is a circular

hole, of about the size to admit three fingers; and immediately above this hole

is a bronze dolphin, which is balanced upon a centre-pin

passing through its middle. The dolphin holds in its mouth a little chain,

which is attached to a small convex metal cymbal, with a flat edge or margin

[like a modem cymbal]. The cymbal is hidden within the cylinder, [it being just

below the hole so that the first puff of air from below will cause it to stop

the hole].

And now, as to the altar-shaped pedestal. In the upper

part, where water is maintained, is the air-condenser, called pnigneus, which is of a convex form, like an inverted

funnel. Under the pnigeus are wedges, which, in

height, are, about equal to the breadth of three fingers, and they maintain a

free space below, for the passage of the water between the lower edges of the pnigeus and the bottom of the vessel.

Above the neck of the pnigeus is the wind-chest for all the pipes, which sustains the upper part of the

organ. The wind-chest is called in Greek The regulator of the music (Canon musicus).

In the wind-chest are air-channels running

longitudinally; four air-channels if for four stops; six for six stops; and

eight for an eight-stopped organ.

Each of these longitudinal air-channels is shut in by

its stop, which is worked by an iron handle. When one of the handles is turned

round, it admits air from the wind-chest into that channel or groove. These

air-channels have transverse holes in them, which open into corresponding holes

above in the table-board, or sound-board of the organ, which is called in Greek

“The Register-table” (pinax).

Sliders are interposed between this register-table and

the wind-chest; and these sliders are pierced through with holes which

correspond in size with the transverse holes above-named. The sliders are

oiled, in order that they may easily be pushed in and withdrawn.

These sliders are for stopping the holes, and they are

technically called “The Plinths”, as each forms a kind of basement to an organ

pipe. (Plinthides.) Their sliding in and out

will one way open, and the other way will close the holes that have been bored

for air-passages.

These sliders have iron conductors fixed to them, and

connected with the keys of the organ. Then, the touching of a key will cause a

corresponding movement of its slider.

On the upper side of the before-named register-table

are the holes through which the air must make its egress from the air-channels

into the pipes. These holes have rings fixed in them, into which rings the

orifices of all the pipes are inserted.

And now, to revert to the cylinder of the condensing

syringe. Each cylinder has a tube running from it to connect it with the pnigeus, in which the air is condensed, and out of the pnigeus through its neck, (which is formed by a short

tube,) up to the orifice of the wind-chest, over which orifice a well-turned

valve is placed. When the wind-chest has received its supply of air, this valve

closes the orifice, and does not permit the air to return.

Now, to go back to the lever. When the handle is

raised, it depresses the elbow-joint of the piston, which is at its opposite

extremity, and thus it brings down the piston of the air-cylinder to its lowest

point. Then the dolphin which, as before said, is set upon a centre-pin, lowers the cymbal which hangs from its mouth,

and thus refills the cylinder with air.

On the other hand, when the lever raises the

piston-rod, and the piston is worked with vigorous frequency, it closes the

hole above the cymbal, and then the enclosed air is driven, by the pressure of

the piston, into the tube. Through the tube the air passes into the pnigeus, and from the pnigeus,

through the second tube, into the wind-chest. By continued vigorous movement of

the lever, the air being frequently compressed, it flows through the apertures

left open by the organ stops, and refills the air-channels that are included in

the wind-chest with air.

Therefore, when the keys of the organ are touched by

the hands, they, continually propel and bring back the sliders, alternately

closing and opening the holes. Thus, by the art of music, these pipes send

forth their resounding tones, with manifold varieties of modulations.

I have endeavoured, to the

best of my ability, to explain this obscure subject in writing; but it is not

an easy matter. Neither will this explanation be intelligible to all, beyond

those who have had some practice in things of this kind. But if they can

understand but little from this description, yet, when they know the thing

itself, they will certainly cap. 13.) find every part of it to be curiously and

ingeniously arranged.

From the above it will he evident that there were

organs with four, six, and eight stops before the birth of Christ; and, as a

consequence, that they had different qualities of tone. The reed principle was

so fully understood, and so much in favour, that its

application to the organ cannot reasonably be doubted. Organ pipes must have

had sliders to close or open them, and when there was any music worthy of the

name, these sliders could only have been managed by the fingers acting upon

keys.

Before parting with Vitruvius, a few words may be said

about the metal vessels fixed in open spaces among the seats, or otherwise near

to the audience, in Greek theatres, which vessels he describes in his fifth

book.- They were an ingenious and scientific contrivance for assisting both

voice and instrument, and the principle upon which they were constructed may be

thus familiarly explained.

It is a well-known fact that, when a harp and a

pianoforte are in the same room, and in precise tune together, a chord struck

upon the pianoforte will produce a corresponding chord from the harp. The

sound-waves that the pianoforte has set into vibration have reached the strings

of the harp, and they have sufficient power to excite new sounds in unison with

them, from the tightly drawn strings of the harp. The effect will be the same

with two pianofortes if the dampers are up, and with other instruments. This

principle was well understood by the ancients. It is referred to both by

Aristotle and by Aristides Quintilianus. It differs, from echo, which is but a

reverberation of one sound. The main body of sound travels like a billiard

ball, and it will either be returned or deflected according to the angle at

which it strikes the object.

The Greek vessels in theatres were for the purpose of

utilizing this waste power. The sound-waves that were acting upon the ear of

the listener were at the same instant exciting new waves of sound from another

body, by setting it also into vibration as a sound-board, when they would

otherwise have been deflected, or had travelled away.

The vessels must have had either a contracted edge or

lip, or else a hole in them. Sound may be produced from air set in vibration by

the edge of a reed, as in a pandaean pipe; or from

the lip of a phial, or from the hole in a flute; but no sound will ensue from

blowing into a tea-cup. In that case the breath will only be deflected. It

requires the strong friction of a wet finger round the edge of a tea-cup, or of

a finger-glass, to set so wide-mouthed a body into vibration.

The vessels thus set round the theatre were tuned to

the different notes of scales, even to quarter-tones, because each vessel could

produce but one note. It is strange that this scientific contrivance should not

have been utilized in any way by the modems, with the well-known fact of the

harp and pianoforte before them. Surely it is preferable to reverberation, both

from its adding power, and from its simultaneousness.

About eighty, years after Vitruvius wrote,

improvements were made, or attempted, in the Hydraulic Organ, but the nature of

those improvements is nowhere explained. Suetonius reports of the Emperor Nero

that, having finished a consultation hurriedly when his enemies were

approaching, he passed the remainder of the day in exhibiting and in discussing

the properties of Hydraulic Organs of a new kind, which he had resolved to

bring out. Just before his death, Nero vowed that, if he escaped the danger

then threatening him, he would appear upon the stage to contend for victory on

the Hydraulic Organ, on the pipe for accompanying choruses, and on the bagpipe;

also that, on the last day of the games, he would appear as an actor and as a

dancer. All these delights were lost to the Romans by his enforced suicide.

There are extant medals of the reign of this Emperor,

and of several other Roman Emperors, which were given for victories gained in

public contests of organ-playing upon the Hydraulic Organ. One such medal, of

the time of Nero, is in the British Museum, and it has on one side the head of

the Emperor, with the inscription, Imp. Nero Caesar Aug. P. Max. The letters

are, as usual, in capitals, without stops between them. If in full, it would

have been, Imperator Nero, Caesar Augustus, Pontifex Maximus. He was indeed a

strange specimen for a high priest. On the reverse of the medal is the portrait

of the victorious organist, and the inscription, Laurenti nica, (The victory of Laurentius). The victor stands

beside his organ, with a branch of laurel raised high in his right hand. Laurel

is upon the front of the organ, and on the further side from the organist also

are two branches, where one of the condensing syringes should be. The limit of

space did not permit the introduction of either of the condensing syringes into

the medal.

There are other such medals of the reigns of the

Emperors Trajan, Caracalla, and Valentinian, in the same collection. The

last-named has the inscription Placeas Petri. In that we have a side view of the organist who is seated, and of

two organ blowers who are working at the condensing syringes, one on each side

of the organ. A front row of nineteen pipes is to be seen; but, in all such

cases, the number of pipes has been restricted by want of space. Engravings

from medals of the same class, and copied from coins which are extant in

foreign cabinets, are depicted in Description General des Medallions contorniates, by J. Sabatier. In describing one of the

time of the Emperor Trajan, Sabatier has mistaken the laurel of the victor for

a flabellum.

In spite of these medals being contorniate,

or having an outer rim turned by the lathe, and raised to protect them, they

are much worn, and consequently indistinct. They are all seemingly of copper,

which is much softer than bronze. For this reason, I select an example from an

antique gem. It is a cornelian intaglio, formerly in the Hertz Collection, and

now in the British Museum. As it would be too minute to be distinct if

exhibited in the gem size of the original, it has been enlarged by our artist.

He could not determine the character of the ornament upon the pedestal of the

organ, but Mr. Murray, of the British Museum, has since kindly informed me that

it is a wreath of laurel, and should have been carried round the centre of the pedestal. The gem seems to have been intended

for the finger, being nearly the length of a finger-joint. It was found to be

too narrow to admit of the portrait of the organist by the side of his

indispensable organ, if the organ blowers were to have their share of fame, and

therefore he has been exhibited in full face above it. It is to be regretted

that we cannot ascertain the name of this eminent artist, but even his initials

are not to be deciphered. The medal is peculiar in exhibiting the victor in a

nude state, but it has this advantage, that we may now admire his ribs and his

collar bone, as well as his good-humoured face. So

great a celebrity deserves something more than a mere bust.

The two organ blowers have, one the lever up and the

other down; thus to work alternately, and so to diminish the spasmodic

injection of the air. The portrait of the before-named victor, Laurentius, may

be seen in Dr. William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, (under Hydraula). A third organist,

but one looking more like a woman than a man, is exhibited on another coin of

Nero, and by the side of that organ is a horn-blower, with a curved horn made

of metal, and of the largest size a very base instrument. The horn is curved

over the player’s shoulder, and it passes under his arm, to his mouth. A spear

crosses the circle described by the horn, and is seemingly there placed for the

purpose of steadying the horn.

Tertullian, the most ancient of the Latin Fathers of

the Church, and who flourished in and after the end of the second century,

compares the soul of man to the Hydraulic Organ. As the soul animates the human

body, and acts in every part of it, so does the wind which fills the organ.

Behold, says he, the highly portentous and munificent

bequest of Archimedes, I mean the

Hydraulic Organ. So many members of that body, so many parts, so many joints,

so many channels for utterance, such union of different sounds, such

interchanges between time, measure, and mode, and so many rows of pipes; yet

all together form but one huge pile! So the breath, which there pants by the

tossing about of the water, will not be separated into parts, because it is

administered through parts; it remains entire in essence though divided in its

working.

Tertullian was too full of his main subject to think

twice as to whether he was ascribing the invention of the Hydraulic Organ to

the right person. He stands alone in attributing it to Archimedes. Not only his

cotemporary, Athenseus, but also Vitruvius before,

and Pliny after his time, unite in ascribing it to Ctesibius,

as do all earlier writers.

Three names were given to the sliders of the Hydraulic

Organ. First, Heron describes them as plinths to the pipes; next, Vitruvius, as

straight pieces of wood (regulae); and

Publilius Optatianiis Porphyrius, a Roman poet of the

age of Constantine I, terms them the square plectra. This was, no doubt,

from their acting like the plectra of the lyre in exciting sound, although from

pipes. The wind itself had a stronger claim to the designation of plectrum, in

an organ. These changes in the names of sliders have been a puzzle to all commentators.

As I shall not again speak of the plectrum, it is well

to notice two Latin idioms, intus canere, and foris canere. In touching the lyre with the plectrum,

the hand was projected outwards, and so away from the lyre. That was foris canere. The

fingers of the left hand were behind the strings of the lyre, and when they

were used in playing, the fingers were drawn in towards the palm of the hand

and the body of the player. That was intus canere. Hence, intus canere became proverbial for the action of a

petty thief, who would draw in anything upon which he could lay his hands, and

sometimes also for a glutton. Again, thieves were, for a like reason, hinted at

as Aspendii Citharistae,

because Aspendius was a famous performer on the lyre

and cithara, who rejected the use of a plectrum, and played upon all the

strings of the cithara with his left hand. Therefore his performances were

altogether of the intus canereclass.

Cicero compares Verres to Aspendius in one of his

orations, and Asconius comments upon the passage; but

it is desirable that the modern reader should know the position of the hands

upon the cithara in order to appreciate the two allusions.

The Hydraulic Organ forms the subject of one of the

poems of the before-named Publilius Optatianus. For some reason now unknown, he

had been banished from Rome; and, in order to be allowed to return, he

addressed a panegyric in the form of a set of short poems to the Emperor

Constantine I. This flattery was sufficiently acceptable to Constantine to

accomplish the object of the poet; and, further, it established him in the

Emperor’s favour.

Among these poems are three which are respectively

entitled An Altar, A Syrinx, and Organon, which is the Hydraulic Organ.

The last is a fanciful composition, which is intended

to resemble the form of the organ. Between twenty-six short iambics and

twenty-six hexameters a single long line runs vertically, from the top to the

bottom of the poem. This may be supposed to represent the edge of the

register-board, upon the surface of which the pipes are placed. The

twenty-six hexameter lines represent a row of pipes, and each hexameter

increases by one letter in each succeeding line, just as the pipes increase in

height. The short iambics may be designed for the body of the organ below the

register-table. It is difficult to decide whether so, or for back rows of

pipes. The pipes are described as of copper or bronze, accompanied by others of

reed. The organ is to be so powerful as to be capable of causing the hearers to

tremble. The length of the pipes is no further defined than that the smallest

is represented by twenty-five letters, and the largest by fifty, thus making

twenty-six in a row. The only guess that can be formed as to the length of the

pipes is from the allusion to the trembling of the hearers. If the organ could

cause a rumbling sensation through the body of the listener, there must have

been pipes of at least 16 feet in length, but probably longer. Cassiodorus

compares the organ to a tower, and the preceding quotation from Tertullian

represents it as a grand pile (moles). Optatian speaks of organ-blowers only in the plural number, without specifying the

precise number.

So many Roman Emperors admired the tone and the power

of the organ that, considering first the public competitions in playing, and

secondly the wealth of the empire, coupled with the luxurious extravagances of

both emperors and patricians, we may

reasonably assume at least the occasional use of the largest pipes from which

sound could be produced. There can be but little doubt as to experiments having

been made upon the largest scale. In the character of the Roman nobles, by Ammianus Marcellinus, written about the year 380, and quoted by Gibbon in

chapter XXXI, he says :

But the costly instruments of the theatre, flutes, and

enormous lyres and Hydraulic Organs are constructed for their use; and the

harmony of vocal and instrumental music is incessantly repeated in the palaces

of Rome. In these palaces sound is preferred to sense, and the care of the body

to that of the mind.

Having enlarged upon the pith of Optatian’s poem, his description of the organ may be transferred to a note. In order to

observe his self-imposed task of making each succeeding line to consist of

exactly one letter more than the former, Optatian seems to have been driven into writing quis for queis, and into

spelling rythmus instead of rhythmus.

It is assumed that M. Danjou was the first of the

moderns who counted the letters of Optatias’ verses,

and so found out their design. Attention was drawn to this fact by my learned

friend, the Chevalier E. de Coussemaker, when

discussing the difficult subject of the musical instruments of the Middle Ages in the Annales Archaeologiques of Didron, in and after the year 1844. I cannot follow M. Danjou in his further

inference that, because the letters increase in length in each hexameter

instead of decreasing, therefore the shortest pipes were on the left of the

ancient player, and he must have played the longest pipes, which form the base

of the organ, with his right hand instead of his left. There are undoubtedly

some representations of organs in that form, but they are overbalanced by

others which are not so. On the two medals of Nero’s date the one is; and the

other is not. An engraver who was not an organ player, but a spectator, would

perhaps accustom his eye to the view he had taken when facing the organist, and

so would place the long pipes on the right. The light touch and the wandering

finger were far more probably employed upon the smaller and more

quickly-speaking pipes than upon the large ones.

Again, an engraver may have thought it a matter of

indifference which view he gave of the organ, or he may have forgotten to

invert the whole of the design from right to left for a transfer to a seal or

to a die.

The poems of Optatian may he

dated in or before the year 324, because, in one of the set, he lauds Crispus,

the brave and accomplished eldest son of Constantine, who was put to death by

his jealous father in that year.

Among the remaining passages from ancient authors

which might be quoted as referring to the Hydraulic Organ, I do not observe one

which will throw further light upon the construction or the character of

the instrument, and only such are here required. I therefore pass on to the

Pneumatic Organ, or organ blown by bellows, more or less after the present

manner.

Since the bellows by which the organ was inflated are

the distinguishing feature, it may be well to show first how these ancient

bellows were worked.

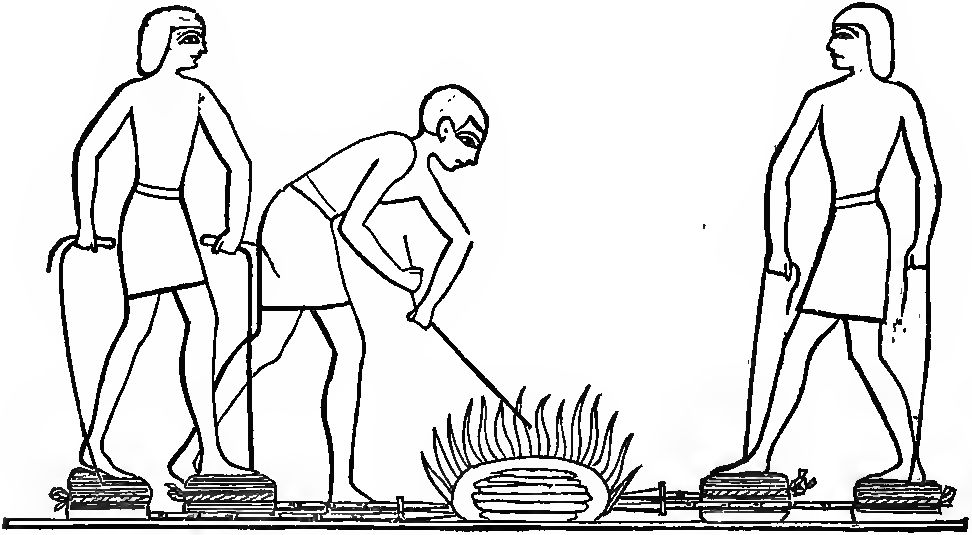

In one of the tombs at Kourna is a painting of an Egyptian smithy; the smith is heating a rod of iron, and

his two assistants are blowing the bellows. These are, in every sense, pairs of

bellows, for the blower has one under each foot. He throws the weight of his

body first upon one leg, and then upon the other, drawing up the exhausted

bellows at each movement of his body by a string. This mode of action

proves that in ancient times bellows were furnished with valves, like those of

the present day; for, if otherwise, the exhausted bellows could not have been

thus drawn up by the hand. The weight of depressing, and the weight of

raising, would have been equal.

If we now turn to Herodotus, we shall find, through an

interpretation which the Lacedaemonians gave to an Oracle, that the ancient

Arcadians, the most primitive of Greeks, employed bellows of the same

character.

The Lacedaemonians had been repeatedly overcome in war

by the Tegeans, and therefore sent to the Oracle at Delphi to enquire which of

the gods they should propitiate in order to become victorious over the Tegeans.

The prophetes,

or priest, who interpreted the Oracle, judging wisely that, as the

Lacedaemonians were a brave people and had set their minds upon it, their turn

must eventually come, answered that the Lacedaemonians should become victorious

over the Tegeans. It would have been unsafe for the reputation of the Oracle

that it should predict a particular date, lest the Tegeans should still be too

strong; so the Pythian was reported to have added: When they had brought back

the bones of Orestes, the son of Agamemnon. That was indeed a safe prophecy,

for the Lacedaemonians knew absolutely less about the bones of Orestes than we

do about the bones of Moses. They could not even tell in what country Orestes

had died. If, then, the Lacedaemonians should again be beaten, although they

had brought home certain bones which they supposed to be those of Orestes, it

would be argued that the Oracle was true, and that the error was altogether on

the part of the Lacedaemonians, in having brought home the bones of the wrong

person.

A further advantage was to be gained by

the charming vagueness of the reply. It must entail a second consultation

of the Oracle; and then the brief was likely to be endorsed with a liberal

consultation fee, considering the weight of the cause, the promise of success

already made, and the desirability of propitiating the god through his

ministers.

All was wisely judged. The Lacedaemonians went a

second time to entreat further information. The priests still took care to have

plenty of loophole, for they alone could interpret the Pythian. They instructed

the Lacedaemonians to search for the bones of Orestes in the enemy’s country;

to

Seek for them where two winds with strong compulsion

are blowing,

Stroke ever answering stroke, and woe upon woe ever

growing.

This lucid exposition gave considerable occupation to

Lacedaemonian brains, but luckily there was one sagacious fellow among them,

named Lichas. He had heard from a smith, (whether

blacksmith or whitesmith is not expressed,) that being about to dig a well by

his smithy, in Tegea, he had found there the body of a man of great size, which

had been buried upon the spot. This was enough for one so acute in making

discoveries as Lichas. He hired the smithy, stole the

bones, and carried them off to Sparta. For seeing the smith’s two bellows, he

discerned in them the two winds, and in the anvil and hammer the stroke

answering to stroke, and in the iron that was being forged the woe that grew on

woe; representing that iron had been invented to the injury of man. Such

confidence did he inspire into the Lacedaemonians as to his having fulfilled the prophecy, that they were fully convinced they could

then beat the Tegeans, and so they did.

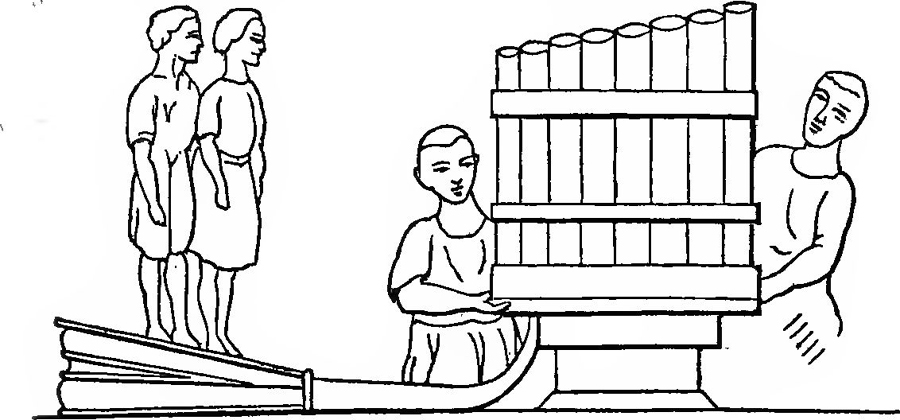

And now as to the Roman method of inflation. We may

descend to the fourth century of the Christian era, and yet we find the same

bellows employed for Pneumatic Organs, according to the sculptures upon the

Obelisk of Theodosius. This Obelisk was erected in the Hippodrome at

Constantinople, and on its white marble base are three pipers playing upon

double pipes, seven dancers, and two Pneumatic Organs, one having larger pipes

than the other.

A representation of the entire subject would exceed

the width of the present page, and the curious may see it in the Annales Archaeologiques of Didron for 1845 (p. 277). It is included in

one of the learned articles upon musical instruments, more especially those of

the Middle Ages, by M. de Coussemaker. The

representation is necessarily minute even in the quarto page of Didron; and, since one of the organs is alone required, I

have availed myself of the following woodcut of larger size from The History

of the Organ by my friends Dr. Rimbault and Mr. E. J. Hopkins, by the

kindness of Messrs. R. Cocks & Co.

These two men, or boys, ought to have strings in their

hands, and to be standing upon different bellows. All that can be said as to

this deficiency is, that the sculptor has not descended to minutiae. The boys

could be of no possible use as they are represented in the engraving.

In point of date the Pneumatic system for the organ is

probably long anterior to the Hydraulic. Heron’s work was evidently intended to

describe only such inventions as were then recent, or which had some

peculiarities not generally understood. For that reason, probably, the only

representation of the Pneumatic Organ included in his book is of one with a windmill

acting upon the piston of a condensing syringe. Thus it drives air directly

into the wind-chest of the organ, without the intermediate action of a

condenser. The pairs of bellows might not have been worked so easily by a

windmill as could a piston, but the organist would only be able to perform upon

the wind-mill-instrument when there was a sufficiently high wind.

The main difficulty in identifying the organ among

casual notices of musical instruments by Greek or Roman writers rests upon the

wide significations of organon and organum. The

organ may sometimes have been intended, even when the word syrinx is

used; for Philon explains an organ to be a syrinx played by the hands. The four

principles of musical pipes were evidently so well understood by the ancients,

that it would be strange indeed if they had not utilised reeds which were too large

for the mouth, and too long to be carried about in the hands. Still, we cannot

look back for the organ to any barbarous age. A love of harmony, and of hearing

several instruments in concert, must have arisen before the organ would have

been brought into ordinary use.

The word organ retained its wide application to

musical instruments of all classes, down to the times of the fathers of the

Christian Church. For instance, St. Augustine says that all musical instruments

are called organs, not merely

the organ which is of large dimensions, and which is blown by bellows, but also

every kind of instrument upon which a tune can be played, or which may be used

for accompanying the voice.

The Emperor Julian wrote an epigram upon the Pneumatic

Organ, in which he alludes to its metal pipes and to its leathern bellows. As

the epigram is written in the form of an enigma, it is less easy to translate.

Dr. Burney, Dr. Busby, and others, accomplished it by passing over some of

the words, I therefore attempt a more literal version.

I see reeds, or pipes, of a different kind : I ween

that from another, a metallic

soil, they have perchance rather sprung up. These are agitated wildly, and not

by our breath; but a blast, rushing from within the hollow of a bull’s hide,

passes underneath, below the foundation of the well-pierced pipes, and a

skilled artist, possessed of nimble fingers, regulates by his wandering touch

the connecting rods of the pipes, and these rods, softly springing to his

touch, express [squeeze out] the song.

There are several words in the above which will bear

two constructions, and thus may form an enigma. For instance, donax is not only a reed shaken by the wind,

and a reed pipe, but also a metal organ pipe. Theodoret uses calamus in the last sense, in a

comparison included in the third of his Ten Orations on Providence,

where he says : It is like a musical organ which consists of copper or

bronze pipes, inflated by leather bellows, and which, when played upon by the

fingers of a skilled musician, produces that enharmonic reverberation of sound.

Cassiodorus, who was Consul of Rome in 514, retired in

the latter part of his life to a monastery of his own founding. He there wrote,

among other works, certain Commentaries on the Psalms, which

he acknowledged to be, in a great measure, derived from the comments of St.

Augustine. In his exposition of the 150th Psalm, Cassiodorus thus describes the

organ of his day:The or gan,

therefore, is like a tower, made of different pipes, from which, by the blowing

of bellows, a most copious sound is secured; and, in order that a suitable

modulation may regulate the sounds, it is constructed with certain tongues of

wood from the interior, which the fingers of the masters, duly pressing (or

forcing back), elicit a full-sounding and most sweet song.

In this last quotation, there is some doubt whether he

may not mean an organ with sliders only; for the word reprimentes would

apply equally to pressing down a key and to forcing back a slider which last is the effect produced by pressing a key. We have in this case a

Roman, instead of a Greek, writer before us; and one whose date falls within

what were once termed the Dark Ages. They were indeed dark as to music. The

organ was then falling into disuse in Rome; and, consequently, the art of its

construction was soon afterwards lost.

It is from passages of this indefinite class, and from

descriptions of rudely constructed instruments of later date, that the

employment of keys in ancient organs has been doubted. Cassiodorus speaks of

organists in the plural number; two would, indeed, be required if the organ had

but sliders. On the other hand, he refers to playing it with the fingers, and

not with the entire hand, therefore it is still to be assumed that the organ

was provided with keys. If the instrument had sliders, and no keys to command

them, either the entire hand or the forefinger and thumb would be used, and not

merely the fingers.

The last notable point in the quotation from

Cassiodorus is, that the sounds produced by the organists are not termed

harmony (concentum), but simply an air (cantilenam). This may be because he sums up the

whole effect as one; but, if to be taken literally, how greatly must the art of

organ-playing have declined in the early part of the sixth century, supposing

two persons to have been required to play the treble and base of an air! The

doubts of our earlier historians as to Greek and Roman organs having been

furnished with keys are to be accounted for by their not having known the Pneumatika of Heron. Neither Dr. Burney nor Sir John

Hawkins refers to Heron’s work in their Histories, nor would they expect to

find a description of the Hydraulic Organ in a work professedly on Pneumatics.

Each, therefore, required better data to enable him to form a sound judgment.

GREEK WORDS MISAPPLIED

Having now brought down an account of the organ from

its earliest known date to the sixth century, its future history will pass

through the ordeal of a second infancy of music, in the Middle Ages,

before that noble instrument can emerge in its full powers. The obscurity which

reigned in those ages was originally and mainly due to the indifference which

had so long characterized the Romans as to arts and sciences which would

neither tend to their pecuniary advantage, nor assist them to an advance in the

State. Neither in the times of Roman virtue, nor in those after times of luxury

and self-indulgence, do we find symptoms of that earnest desire for knowledge

which was characteristic of the ancient Greeks. It would be vain to search for

a Socrates, a Plato, an Aristotle, a Didymus, or even a Claudius Ptolemy, among

Romans. Bunsen has said, rather severely, that the divine thirst for knowledge

for its own sake, or for truth from a love of truth, never disturbed a Roman

mind.

After they had conquered the Greeks, the Romans

embellished their own language by so large an importation of Greek words, as to

form no inconsiderable part of a modern Latin dictionary; but partly from

inattention, and partly from insufficient knowledge of the Greek tongue, they

so misapplied many of the words, as to cause the greatest perplexity to such

after-enquirers as have sought to learn Greek arts through the medium of Latin

interpretations.

This was especially the case in music, but the

misapplication of Greek terms extended far beyond that greatest of arts. Even

in architecture, upon which the Romans especially prided themselves,

indifference as to the preservation of right meanings of words was equally

manifest. Vitruvius comments upon some of these misapplied terms in his book ; but, like a true Roman, not from any desire

to see them restored to their proper places, but simply to explain the words

for the benefit of philologists.

Unhappily, there was no Vitruvius to explain to us the

misappropriation of Greek terms in music, and, consequently, they have

remained, to this time, the great stumbling-block to an intelligent

appreciation of the Greek system.

Further than this, Western Europe was taught through

the Latin medium that there are but three accents (prosodiai)

in the Greek language. Discussions have consequently been carried on for more

than a century, and many of the ablest scholars in Europe have taken part in

them, to decide whether Greek accents have that quantity in them which

characterizes the accents of modern Europe, or whether they have not. Each

side, indeed, might claim to have been right, according to its different

acceptation of the word accents or prosodiai;

for, while the acute and the grave accents have neither stress nor

quantity assigned to them by any ancient Greek author, there are other prosodiai which have quantity. Again, there is one

for hard breathing, therefore it involves the stress which has been claimed for

them.

Ancient authorities define accents as of three kinds;

the first, for the pitch of the sound; the second, for its duration; and the

third, for the hard or soft breathing of vowels and consonants. The three which

are for pitch are the acute, the grave, and the circumflex accents; the two for

time are identical with those which are still used in prosody to mark long and

short syllables; and the two for the management of the breath are the

well-known signs which are placed over Greek vowels, to denote hard or soft

breathings. Some writers, indeed, add three more to the above seven, viz., the

apostrophe, the hyphen, and the short stop called hypodiastole,

but no marks, which were on the same level or under the words, are generally

admitted among prosodiai.

Prosodiai were signs to guide the voice in recitation of all kinds, and out of

those accents grew the systems of ecclesiastical notation, called pneumata guides for the management of the breath, now called neumes. These are

abundantly exhibited in manuscripts of the Eastern, and of the early Western,

Churches; but the two divisions worked out their systems differently. Neumes

did not originally designate any definite notes or pitch, because musical

intervals were not required in recitation. If any fixed musical sounds had been

designed, letters over the words would necessarily have been employed, as in

Greek music, instead of such indefinite marks.

In the course of after-ages, some of the scribes

attached to the Western Church drew faint lines through each row of the neumes

with a plummet, while others painted coloured lines

through them, first one, and afterwards two lines red and saffron. These were to guide as to the starting notes of the

chants, and as to the degrees of ascent or descent for the voice. Thus the

present musical notation by lines and spaces had its origin. Square and round