|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

THE HISTORY OF MUSIC (art and Science) FROM THE EARLIEST RECORDS TO THE FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE.CHAPTER X.

The musical

instruments of the ancients.

The musical instruments of the ancients have always

been found a difficult subject to treat upon; and for several reasons. The

first is, because only a limited number of the instruments named by classical

authors can be thoroughly identified. This is partly owing to the absence of

contemporary representations in sculpture or in paintings; and even when such

are to be found, too much poetical license has not infrequently been taken with

their forms, and they are rarely accompanied by distinctive names. Such allusions

to them as are to be found in the texts are generally casual and brief, and

often very indefinite. In these cases, other notices have to be sought for,

sometimes far and wide; they are then to be collected together, and to be

compared.

When all this has been done, the descriptions have

often an appearance of being contradictory, and the next step must be to endeavour to trace the source of this seeming

contradiction. Sometimes it will be found that a name has been varied on

account of a slight, and, perhaps, unimportant difference of pattern, or in the

material of which the instrument was made. It is next to impossible to

distinguish such differences in sculpture, and hardly less so in paintings,

without a previous minute knowledge of what is to be sought for. Again, the

same material may have supplied names to widely differing instruments; and,

lastly, some even of the ancients, who undertook to describe them, were not

musically qualified for the task.

This was especially the case with Athenaeus, to whom

we are, nevertheless, more indebted than to any other writer, for having

collected together a large number of extracts concerning musical instruments.

Athenaeus had little or no knowledge of their construction, although he seems

to have taken particular pleasure in hearing music. If there were no other

description extant of the Hydraulikon, or Hydraulic

Organ, than the one he has given, it would now be classed among mythical

instruments. Fortunately there exist two other good and even minute

descriptions. According to Athenaeus, the Hydraulic Organ was inflated with

water, and the pipes were turned down into the water. Then the water was

strenuously agitated by a youth, and thus the pipes were made to emit an

agreeable sound.

This is just such a description as might have been

given by any careless observer, who knew nothing of hydraulics or pneumatics,

and who did not trouble himself to enquire into the principle of the

instrument. Anyone who has once heard the rush of water through a pipe into a

cistern, after the turncock has turned on the water-supply to a house, will be

able to judge whether a series of such pipes would emit agreeable sounds. It is not too much to say that no really musical instrument was ever

constructed upon such a principle, although the attempt has certainly been made

in consequence of Athenaeus’s description. The true Hydraulic Organ will here

be shown to have been of a very different character.

Again, the reader must not expect help, as to music,

from the generality of old Latin translations, such as that of Julius Pollux’s Onomastikon. Many musical instruments are enumerated in the Greek text, but the author

of the Latin version knew so little about Greek poetry and Greek music that he

could not distinguish between a Mode and a Nome, i.e., between a

scale and a hymn. It is, therefore, hardly a matter for surprise that he

supposed flutes to have been played upon by strings, instead of by wind.

Translations of the same description are by no means so uncommon as many would

gladly suppose, but one such instance will suffice for present purpose.

General names create one of the greatest difficulties

to the enquirer into ancient musical instruments; and his first thought should

be: “Is this a generic or a particular name?”. In the case of the Magadis, or Octave-playing instrument, many

seemingly conflicting descriptions are collected by Athenaeus. All are

reconcilable the moment it is understood that the name Magadis was transferable to any stringed or wind instrument that might be played in

Octaves. The name was originally given to a foreign instrument. It was a Lydian Magadis upon which Anacreon played, that had

twenty strings.

Again, the Sambuca, in Greek, Sambuke,

is described by one as a small triangular harp with four strings, and of such

high sounds as to make it practically of little use. That kind of Sambuca was a

small Trigon. By a second, it is identified with the Barbitos,

or many-stringed Lyre. By a third writer, it is made a synonyme for the Lyro-phoenix, or Phoenician Lyre. In a fourth

case, it is the large Greek Lyre. In a fifth case, it is a Magadis.

In the middle ages, it was at one time a Dulcimer, and at others a large Pipe.

In a seventh case, it was a Roman military engine, of a light and portable

character, for scaling walls.

It is scarcely to be doubted that the clue to all

these varieties is the word Elderwood. The musical instrument was not

originally Greek, which will account for the root of the word not being Greek;

but the Romans inherited the name as that of the elder tree, in the form of

Sambucus and of Sabucus. Pythagoras and Euphorion speak of the Sambuca as played by the Parthians,

and by nations bordering on the Red Sea. Others again attribute it to the

Phoenicians. Elderwood, when dried, is very light in point of weight; and

first, its portability, and, secondly, its wide grain, would have recommended

it for sonority in stringed musical instruments. Again, the facility with which

the green pith might be removed from its branches made them useful for large

pipes. The system of naming musical instruments after the wood of which they

were made was very common in ancient times. For instance: Boxwood, (Gr. Puxos, Lat. Buxus,) lent its name to

smaller pipes and flutes; because, being a hard and close-grained wood, it was

suitable for exactitude in the bore of their tubes. It was smooth, and took a

good polish, and it would bear rough usage. Clarionets,

flutes, and fifes are still made of boxwood. Both in Greek and in Latin the

name of this wood is often used for the pipe.

There are so many kinds of general names for musical

instruments: some derived from a particular nation, some from an inventor, some from

their special use, and some from their shape, that the more practicable way of

treating the subject, at the present time, seems to be according to the principles involved in their construction, and thus in

classes, instead of individually. It will greatly abbreviate details, and the

various properties of the instruments will be more readily understood.

THE WINDS. THE FIRST TEACHERS.

To which class shall priority be given to wind, string, or percussion? It may justly be argued that melody first

arose between the beats of time that marked rhythm, and therefore rhythm was

the parent of vocal melody; but whether instruments of percussion, like the

drum, are on that account to be ranked as the first of musical instruments, as

Dr. Burney and others would have it, is another question. Upon such a theory

precedence must be given to hands and feet before all instruments, but where is

their musical sound? The distinction between noise and music is, that the first

acts by sudden and irregular shocks, and the second by rapidly succeeding

periodic impulses upon the ear. These impulses give the continuity of tone

which is called music. Rather, then, should the play of the wind upon the ends

of broken reeds be credited with the first suggestion to man of a musical

instrument.

To cut pieces of reed so as to form whistles, was, in

all probability, a thought which preceded that of boring holes into one reed,

so as to make it emit several sounds. Priority may also be assigned to this

practice of blowing at an angle across the ends of the reeds, in the manner of

the wind, before that of twisting a string and attaching it to a

sounding-board, so as to cause it to produce a musical note. And, thirdly, over

the cutting off a part of the horn of an animal, with the object of employing

it as a wind instrument, by inserting the smaller open end into the mouth.

Fond zephyrs playing on the hollow reeds

First taught the rustic how to use his pipe.

The Syrinx of the Greeks is now called Pandean Pipe,

or Pan’s Pipe, and is rarely seen except with the Punch and Judy showman. It

was formed by a combination of short pieces of reed of different lengths, and

they were joined together by waxed threads, and tuned to a scale by filling the

ends with wax, or by cutting down the reeds exactly to the note.

A pipe composed of reeds of lessening height,

By wax conjoined the greater to the less.

Instruments of that kind are common to uncivilized as

well as civilized nations. In consequence of the myth that Pan was the inventor

of such pipes, and that he taught the world how to join the reeds together with

wax and flax, the Syrinx came to be called the Pandura. This name, instead of

Syrinx, was assigned to it only by comparatively late writers, among whom are

Cassiodorus, Hesychius, and Isidore of Seville. It has already been shown that

the more ancient Pandura, or Pandoura, was a stringed instrument.

The Syrinx was one of Nebuchadnezzar’s musical

instruments, according to the Septuagint version of the Book of Daniel, and it

was used by the Lydians in going to battle. Nebuchadnezzar’s comet, flute,

harp, sackbut, psaltery, dulcimer, according to the Greek, were the Salpinx, i.e., trumpet, the Syrinx, the Kithara, the Sambuca, the

psaltery, and the symphonia, the last being but a vague name for some

instrument for harmony.

Theocritus wrote a short poem, under the title of “The

Syrinx.” It consists of twenty lines, in ten pairs of gradually decreasing

length, like the pipes of the instrument. Each of the last pair is composed of

a single word of four syllables. From the ten pairs of lines in this poem it

may be inferred that, at the time it was written, or in the earlier part of the

third century before Christ, the Syrinx had ordinarily ten pipes or reeds. But,

according to sculptures of later date, seven or eight reeds was its more usual

number.

The Syrinx is of an exceptional character. It is not

to be classed with any other, because all other ancient pipes had the wind blown wholly or partially through them; whereas, in

the Syrinx, the wind passes in and out of the same aperture. The breath

directed against the inner edge of the top of the reed causes it to sound, just

as it would upon the inner lip of an empty physic phial.

Setting aside this instrument as one of a peculiar

character, there are four distinct principles upon which ancient musical pipes

and flutes were constructed, and all were acted upon by blowing through at

least some part of the pipe, instead of merely across the end of it, as in the

Syrinx. Out of these have important modern instruments been evolved, as well as

the admirably contrasted tones of organs. All four had their origin in shepherd’

pipes, and were made either out of a reed or of a straw. They may still be

experimented upon with, the original materials, and with the like result.

Shepherds are no longer musical as a class in our

latitudes, but boys in country schools exercise themselves occasionally in the

craft, and many of them would be good teachers of the four different systems.

Having received some instruction, and gained a little practical experience, I

will endeavour to explain them. Two are with a

vibrating tongue of straw or reed, which is to be held in the mouth, and two

are without it.

THE DOUBLE REED,

OR HAUTBOY SYSTEM.

The First Principle is on the Double Reed or Hautboy

system.

Take the pulpy end of a straw of green corn, or one of

the smallest of reeds without a knot, and split one end by squeezing it. Place

the split end between the lips, and blow through the straw. The split part will

act like the double reed of the hautboy, of which the ancient English name was

Waight. That nam was derived from the Castle

Waight, or Watchman, who carried and played upon pipes of this kind at stated

hours of the night.

The experimentalist must vary the strength of his

blowing till he finds the pitch of this tiny tube, or else it will not sound;

and then he can raise or lower the note by shortening the straw or by taking a

longer.

The modern bassoon has a double reed on this same

principle, but it is one of larger size than that of the hautboy. Thus it forms

the appropriate base to the hautboy.

The intermediate instrument was formerly called the

cornet in England, from having been originally made of horn, and still is

called the Corno Inglese. It forms the tenor to the hautboy.

And now to trace back instruments constructed on this

double reed principle.

In the Egyptian collection at the British Museum is a

small reed pipe of eight and three-quarter inches in length, and into the

hollow of this little pipe is fitted at one end a split straw of thick Egyptian

growth, to form its mouthpiece. When compressed by the lips, this mouthpiece

will leave but a tiny space for the admission of the breath. The pipe

corresponds so precisely to the descriptions of the Gingras, given by Greek

writers, as to leave hardly a doubt of its identity. The agreement is not as to

form only, but also as to the wailing tone attributed to the Gingras. That

quality could only be produced by a pipe on the double reed principle. The

Gingras in the British Museum has four holes for the fingers.

Athenaeus, quoting Xenophon, says that the Phoenicians

used a kind of pipe, called the Gingras, about a span in length, of very high

pitch, and of a mournful tone. Also that it was employed by the Carians in

their wailings, and that these pipes were called Gingroi by

the Phoenicians, from the lamentations for Adonis, “for you Phoenicians call

Adonis Gingres, as Democlides tells us.” So this Adonis-pipe was admittedly of

Asiatic origin, and was most likely common to the various nations of Asia, as

well as to Egypt.

Next, the Bombos of the

Greeks signified both the base of a scale and a long pipe that produced very

low notes. Such a pipe was specially used at funerals; and its name, which

signifies humming or buzzing, again suggests the double reed

principle. There would be no buzz without a reed, unless a thin piece of skin

or parchment were made to vibrate, as paper with a comb, and so to parody the

quality of its tone. From a flute of either kind, the tone would be pure, soft,

and weak in the base, whether blown from the end or at the side.

For these reasons, it seems a fair inference that the Bombos of the Greeks, and the Bombard of the middle ages,

are now most nearly represented by the bassoon. But there is this difference

that, whereas the Bombos was a very long pipe, the

wooden tube of the bassoon, which would be equally long if straight, is curved

back in the middle, or folded in two, in order to avoid the inconvenience of

great length. A curved end is therefore necessary to keep the face of the

player away from his returned breath. The reed is inserted into the curved end,

which is usually made of brass.

Some Etruscan Pipes show the double reed very clearly.

The Etruscans seem to have had a great preference for such pipes. Among their

musical instruments are lyres, tabrets or tambourines, with gingling little cymbals attached to them, and the Syrinx. Although the harp is less

frequently exhibited, there is at least one specimen to be found on an Etruscan

vase in the British Museum.

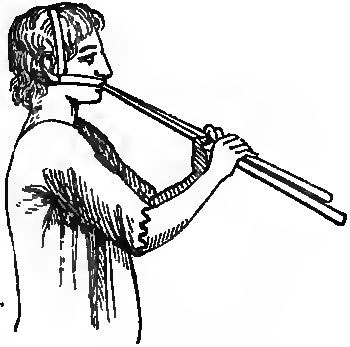

In the following representation, a Roman holds two

conical pipes, which are therefore the true hautboy, as are some of the

Etruscan. The original of the picture is in the British Museum, case 67.

THE SINGLE REED, OR CLARIONET SYSTEM.

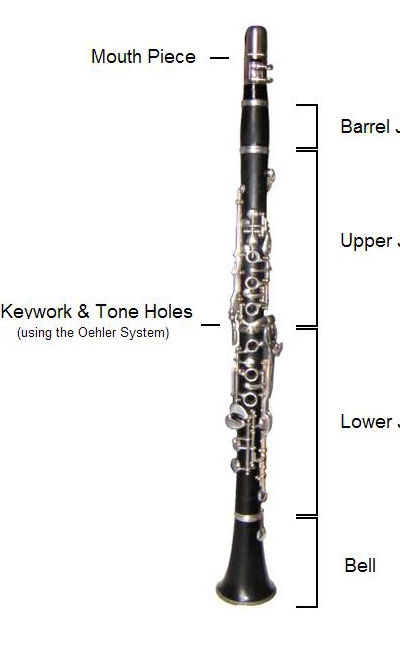

The Second Principle is that of the Single Reed or Clarionet system.

Take a straw with a knot at one end and open at the

other. To borrow Professor Tyndall’s words: At about an inch from the knot, cut

lightly with a penknife to the depth of about a quarter of the straw’s

diameter. Then, turning the blade flat, pass it upwards towards the knot, and

so raise a strip of the straw, nearly an inch long. This strip will be the reed

or tongue, to be set in vibration by the breath passing down upon it into the

pipe. The straw may be cut the reverse way, that is, beginning from the knot,

and with the same effect. The tongue of straw is so pliable as not to require

pressure from the lip, as it would in the case of a reed.

Such was the principle of the ordinary pipe of the

ancients. The greater depth and volume of tone that could be produced from the

middle and lower notes by the employment of a reed, recommended it especially

for out-door celebrations.

It was the Shawm, Schalm, Schalmuse,

or Chalumeau of a few centuries ago, and it is now represented in an improved

form by the clarionet with keys. The clarionet differs from the hautboy in form as well as in

the reed, for the clarionet is an equal sized tube,

enlarging only at the bell end, but the bell adds nothing to the tone, and

might be discarded. The hautboy has been already described as conical.

In all cases where a reed mouthpiece is required, the

object most desired by players is to obtain a pliable one. The stiffer the reed

the harsher and louder will be the tone produced. There was one case among the

ancients in which a stiff reed became rather desirable than otherwise. That was

in the Pythian games, when the players had to take part in the representation

of the fight between Apollo and the Python. It must have been rather an amusing

exhibition for once seeing. It consisted of five parts. First, the attempt;

second, the provocation; the third an iambic, and the fourth a spondaic

movement; the fifth, the ovation to the god.

APOLLO AND THE PYTHON.

During the first movement Apollo looked about him to

see if the place was convenient for a fight, for even the gods were prudent in

such matters. In the second, Apollo provoked the dragon, and in the third they

fought. This third movement, being in iambic measure, was excellent for

thrusting. While the fight was going on, the pipers had both to play, and now

and then to imitate upon their pipes the hissings of the dragon, the gnashing

of his teeth, and his screams when he was hit by the arrows of the god. (Here

the stiff clarionet reed would be most useful.) The

base trumpets impressively gave out the dragon’s shudders and groans. When the

fight was over, came the stately spondaic movement. That was to represent Apollo’s

victory. Last came the ovation, during the whole of which the god danced to

celebrate his triumph. We are not told the measure of this last movement, but,

having already had both iambic and spondaic, we may suggest anapaestic,

and then we can fancy Apollo carelessly dancing the polka.

For this game the players had especial pipes, called

in Greek Puthauloi, Latin, Pythauli. The same pipes, but not necessarily

with the same stiff reeds, were also used with choruses of voices, and thus

were called also Chorauloi.

The single and double reed principles may be said to

have been by far the more general among Greeks and Romans, especially with the

latter, who required the loudest pipes for the great dimensions of their amphitheatres. Horace refers to pipes of his time as being

bound with copper or bronze, and as emulating the power of the trumpet. He

contrasts them with pipes of more ancient days, which were of small bore,

slender in size, and had few notes. The ancient pipes, said he, accompanied a

chorus, but those of his own time served rather to drown it. This emulation of

the power of the trumpet in pipes seems to have suggested the modem name of clarionet; for a clarion was a trumpet an octave above the

ordinary one, and clarionet is its diminutive. In

this way, the names of instruments are sometimes transferred from one class to

another of widely different character.

Whenever we read of an ancient player who had a box,

in which he kept the reed or tongue of his pipe, (the glotta or glossa,)

we may infer that he used a double, or possibly, a single reed, because they

alone would require the protection. The double reed is the more probable,

because a cap over the end of the pipe would suffice to protect the stronger

single reed. The necessity exists at this day. The clarionet player has a wooden cap to cover the end of his pipe, but no hautboy or bassoon

player would be without a box, into which he fixes his delicate double reeds

when he has ceased to play. The ancient reed-box had a sliding top, like a

modem box for dominos. The slide is described in Heron’s explanation of the

Hydraulic Organ. The double reed principle is nearest to that of the human

voice; but, as the reeds are smaller than the aperture at the top of the

throat, their tone has more of the quality that we designate as reedy.

It is next to impossible to identify many of the

pipes. The names give no sufficient clue to them. Aulos is a

general title that does not distinguish between a pipe and a flute; and the

Latin Tibia is equally indefinite.

Among other materials employed by the ancients, for

pipe or flute, were lotus, laurel, palmwood, pinewood, boxwood, beechwood, elderwood, ivory, reeds of various kinds, leg-bones of

animals and of large birds, such as the eagle, vulture, and kite; horns of

various animals for the bell-ends of certain pipes, and metals of various

sorts. Some pipes derived their names from the special purposes to which they

were devoted, as Spondauloi, for supplication to the

gods; Chorauloi, for accompanying choruses; Chorikoi, for accompanying choral dancings;

Dactylic pipes, for a kind of dancing which must have been in common time, from

its name; Hippophorboi, for horsekeepers,

whose pipes were made of the bark of the laurel; others for travellers,

and so on.

Again, pipes were sometimes named after the country or

nation from which the Greeks derived them, as Alexandrian, Tuscan, Theban,

Scythian, Phoenician, Lybian, Arabian, which were

very long pipes; and Phyrgian, or Berecynthian.

The Lybian was a true flute, blown at the side; a Plagiaulos. It was made of lotus, and so was distinct from

the horsekeeper’s flute which was also attributed to Lybia. The Scythian were of eagles or vultures’ legs; and

the Theban were made of the thigh-bone of a fawn, and were covered with metal.

The length of Arabian pipes was proverbial, and a man, of whose tongue there

seemed to be no end, was called an Arabian piper.

The Egyptians had the credit of the many-toned flute,

as they had of the many-stringed instruments.

THE BOMBYX, OR SILKWORM PIPE.

Perhaps another of the ancient pipes may be

identified, from its seeming to answer so well to the descriptions; its name,

Bombyx, supplies the clue, for the pipe bears some resemblance to a

silkworm.

Adrian Junius, in his Nomenclator, quotes

Aristotle to the effect that these pipes were long, required a great deal of

breath, and were blown only with much exertion. If they required exertion, as

well as a great deal of breath, they were wide pipes, and were blown through a

reed mouthpiece. Pliny, in describing the reeds grown in lake Orchomenus, in

Boeotia, says, that one which was pervious throughout was called the piper’s

reed, (auleticon). This reed, says he, used to

take nine years to grow, as it was for that period the waters of the lake were

continually on the increase. If the flood lasted at the full for a year, the

reeds were cut for double pipes (zeugitce), and if

the waters subsided sooner, the reeds were not so fine, were called Bom-byciae, and were used for single pipes. These reeds threw

out shoots around them, and perhaps each row of shoots may have been counted as

a year’s growth. In Burney’s History of Music there

is a representation of a large musical pipe, copied from the beautiful sarcophagus in the Campidoglio, or

Capitoline Museum, at Rome, and this is, in all probability, a Bombyx. Thereon

seem to be the marks of the attributed nine years’ growth, from each of which

the leaves have been cut away, and they give it the appearance of the silkworm’s

body, while the five raised circular apertures may have suggested the idea of

silkworms’ legs. Perhaps, also, the reed was flossy, and thus had a silky

appearance.

These circular apertures were probably made of horn,

and intended as stops by turning them round, and so to close or open the pipe.

Such use appears more probable than that they can have been intended either to

be plugged, or to be stopped by the fingers during the performance. The pipe is

the only large one that I have noticed which can be supposed to bear any

resemblance to the silkworm. The Bombyx, says Julius Pollux, was well fitted

for orgies, on account of its powerful tones.0 If it had been played without a

reed, the tone of the low notes would have been soft and feeble.

The single reeds for mouthpieces, such as we call clarionet reeds, were cut out of Bombyx.

PIPES PLAYED WITHOUT REEDS.

And, now, to the Third and Fourth Principles, which

are those of Flutes and Pipes which are blown, either at the end or at the

side, without the intervention of an artificial reed to increase the power and

to change the quality of the tone.

Of these two, the Plagiaulos,

or flute, blown at the side, as at the present time, is the more powerful. The

reason is, that the lip is made to serve the purpose of a reed, and it sets the

column of air within the pipe into more active vibration. On the other hand,

the flute or pipe blown at the end has a stiff mouthpiece, which precludes the

use of the lip, and the sounds are weaker, but with nearer approach to perfect

purity of tone. The tone is there produced by the breath being directed against

a sharp edge.

Instruments of comparatively modem date will sometimes

serve to illustrate the principles of ancient ones; and it may, therefore, be

noticed that the old English flute, blown at the end, was remarkable for

sweetness, but with little power. In France, (according to Rousseau) it had

three names Flute-bec, Flute douce,

and Flute d’Angleterre. It has a mouthpiece like the

beak of a bird cut short, and the second name exactly describes the kind of

tone. Having once possessed a set of four such flutes, of different sizes, I

may, with more certainty, speak of the general quality as remarkably sweet and

musical, but with little power. The flageolet and the diapason-pipe of an organ

are constructed on this same system, and carry out the description.

For exemplification of this third principle, viz.

instruments blown at the end take a

joint of reed which has a knot at one extreme, and is open at the other. Take

the knotty end for the mouth, and make a narrow slit through the upper part of

the knot, almost to the outside of the reed, so as to admit the breath only

through that slit; then cut a sloping notch out of the body of the pipe, about

an inch from the knot, so as to leave a sharp edge pointing towards the slit.

Against this edge the thin sheet of breath must be directed as it passes

through the slit. When blown, the breath will then flutter rapidly against the

sharp edge, and that edge will sound the pipe. It would not have any musical

sound without it. Such is the principle of the diapason pipes of an organ. The

kind of notch to be made may be seen on the outside of the pipes of an

ornamental organ-front. This also is the principle of the flageolet. Take off

the mouthpiece of a flageolet, and the fine slit through which the breath must

pass will be then seen. The inside of the organ pipe has the same long narrow

aperture, but is not exposed to the eye. The mouthpiece of the flageolet is

added for convenience rather than for use. The pipe may be sounded without it.

The two essential parts are the slit and the notch. If a pipe blown at the end

has no notch it, it, that pipe can only have been intended for a reed.

For exemplification of this principle among the

ancients, we may look back to the Egyptian ladies in the plate at p. 63. One of

them holds two of these pipes, with ivory mouthpieces between her lips. The

mouthpiece is like that of a flageolet, but the pipes are longer. They seem to

be made entirely of reeds, and so would answer to the Kalamauloi of

the Greeks. The notches in the pipes are not shown in this mural painting,

neither are the strings to the lyres in the other portion which forms the

frontispiece, but strings and notch were equally indispensable.

The sweet Monaulos,

which, according to Sophocles and others, was derived from Egypt, and the

invention of which was attributed to Osiris, was the single pipe of this class.

To attribute it to Osiris was about equivalent to saying that it was so very

ancient that the Egyptians knew nothing at all about its origin. It had many

notes; was a shepherd’s pipe; was made of reed; and, on account of the

sweetness of its tone, was especially employed at weddings. Athenaeus collected

notices of this instrument, and, among others, one from Amerias the Macedonian, who calls it the shepherd’s pipe, or Tityrinus.

This last name was derived from the Tityri, or

Satyrs. Again. Athenseus quotes from Alexandrides, “I the Moriaulos took, and played a wedding song; and next, from Protagorides,

He touched every kind of instrument, but drew the sweetest music from the sweet Monaulos.”

Whenever we read of a flute or pipe of remarkably soft

tone, we may infer that it was one of the two kinds played upon without a reed

mouthpiece, and this, blown at the end, would most closely answer to the

description. Such pipes had not sufficient power for a Roman amphitheatre, but were charming in a room. The tone of all

pipes is softest when they have been well moistened by use.

ANCIENT FLUTES.

The Fourth Principle is that of our present Flute,

blown at the side by the help of the lip, and the breath passing down the tube

at a right angle, or nearly so, to the direction of the breath. It is only

within about a century that this one kind has monopolized the name of flute.

Before that date it was distinguished in France and England as the German

Flute, and in Germany as the Swiss Flute. It was called Photinx by the Greeks, and the fact of its being turned laterally for playing, gave it

the second name of a Plagiaulos. The corresponding

name in Latin is Tibia vasca, or Tibia obliqua. It is found among the earliest monuments

of Egypt, and one of great length has been shown in the plate on p. 65, of the

fourth dynasty of Egypt. According to Athenaeus, the Photinx was made of lotus-wood, and he adds that the lotus grows in Lybia.

Modern flutes are not made of such great lengths as

many of the ancient, and consequently they can be held in a horizontal

position. If a flute were so long as to reach to the ground, it would fatigue

the arm to hold it so high as we do for any lengthened time. Our flutes are

held nearly in a balance by the two hands, and in a convenient position for the

mouth, through an extension of the headpiece beyond the mouth. This also

carries the upper end beyond the face, and so with less risk of being pushed into

the eye or mouth of the player. But the principle is not altered. That

headpiece is filled by a plug to within about a quarter of an inch of the hole

through which the flute is blown. So, the long Egyptian flute, into which the

player seems to blow at the very extreme of the side, is the same as our own.

He turns the lower end of his flute rather behind him, so that in case of being

caught by the foot or leg of a passer, the upper end may be directed beyond his

face.

When we see a representation of a man playing a flute

of about one foot in length, we may say, at once, that man is playing the

treble, because the length of his pipe will not sound lower than about treble

C. If the flute is two feet long, he is playing the tenor part, because such a

flute is an Octave below the other. And if four feet long, he is playing the

base, because the length of the instrument, roughly taken, gives C in the base

staff. So our Egyptian performer with the long flute, on page 65, is certainly

playing the base. We could equally tell the compass of the other two pipes

which we see to be blown at the ends, if we could determine whether the pipers

are, or are not, using single reeds. There are no indications of them, and

therefore, in all probability, the music is of the soft English flute kind,

like that of the Egyptian lady represented at page 63; but the three instrumentalists

are undoubtedly playing music in three parts. The shortest pipe may go down to

about a in the treble staff, and the longer pipe is about an Octave lower.

There is no appreciable object for a selection of pipes of such varied lengths

except to play in harmony, and the avoidance of varied sounds would be

impossible when they were used. If the pipes have single reeds, like clarionets, they must still be playing in harmony, but an

Octave lower. There is, however, another reason why it is improbable that

either of the players with the shorter pipes should be employing clarionet reeds, and it is because, in that case, a flute

would make too weak a base for them. On the contrary, such a flute would be

quite an appropriate base for the Egyptian Monaulos,

which was like the old English flute, or the flageolet.

PHOTINX AND MONAULOS.

If the Egyptian pictures have all been copied

correctly, and have not been inverted by the engravers, the flute players

sometimes held their flutes on the left side of the body, and sometimes on the

right. The side-blown flutes were used in the worship of Serapis, and,

according to Apuleius, they were held on the right side, as our own. The

invention of the Photinx was attributed to Osiris, as

well as that of the Monaulos. Each kind was made of

various sizes and lengths. Poseidonius, speaking of a

war which the Apameans were about to wage, says that

they had asses laden with wine and every sort of meat, and by the side of them

were packed little Photinges and little Monauloi, instruments of revelry, and not of war.

Dr. Burney doubly mistook the Photinx when he said, on the one hand, that it was the Monaulos,

and on the other, that it was a crooked flute, and its shape that of a bull’s

horn. He there mixed together three different instruments. Neither the Photinx nor the Monaulos were

crooked, neither was either of them shaped at the end like a horn. An

instrument made of a bull’s horn would have been a Keras,

literally horn; and a pipe with a horn at the end, or a horn blown at the side,

would have been a Keraulos, or horn-pipe. The Monaulos and the Photinx were

both straight, and the difference between the two was, that the first was blown

at the end, and the second at the side.

Dr. Burney was possibly thinking of the deep-toned Berecynthian pipes which were named from Berecynthus, in Phrygia, and were, therefore, also called

Phrygian. Horace refers to these pipes in the first Ode of his fourth Book, and

Ovid to the curved horn in Fasti, lib. iv. line 181 :

Protinus inflexo Berecynthia tibia cornu

Flabit. ....

Athenaeus speaks of the deep-toned Phrygian pipe as

having a horn mouth somewhat like a trumpet, and others say, like Ovid, that

the ends were turned up with horns.

“The Phrygian pipe, says Porphyry, is of smaller bore

than the Greek, and, therefore, emits much graver sounds.” He there assigns a

wrong reason. The bell at the end would lengthen the column of air, and thereby

give a little deeper tone to Phrygian pipes; but, in all probability, they were

like clarionets, blown down into by a single reed,

and so had the character of stopped pipes. That would make them an Octave below

others. The old theory was, that there can be no difference of pitch between

pipes of equal length upon any other principle than that of the one being a

stopped pipe, whether wide or narrow, for width was supposed only to increase

loudness. Practically, the variation is very trifling when the length is but 2

or 3 feet; but, when pipes are upon a much larger scale, the increase of

diameter sensibly flattens the pitch. If the pipes in question had reeds like clarionets, the expanding mouth would make no difference in

the power of tone. In a trumpet, it is the reverse, for all power depends upon

the bell. It is difficult to account for a clarionet having the properties of a stopped pipe, but the only Harmonics it produces are

two Twelfths, one above the other, and the breath cannot produce a third

Harmonic.

PHRYGIAN AND BERECYNTHIAN PIPES.

Phrygian pipes are described by Aristides Quintilianus

as of a feminine character, for wailing and lamenting. From that it must be

inferred that some were on the hautboy and bassoon principle, played with

double reeds, So there were Phrygian pipes other than Berecynthian,

and it is the more certain, because Aristides contrasts them with the Pythic,

which were on the single reed or clarionet principle,

and he describes the last as of lower pitch, and having more virility, or

power, than the Phrygian.

The Phrygian are commonly spoken of as double pipes,

and sometimes as equal, and at others as of unequal length. Octaves might be

played upon two pipes without doubling the length of one of them, if a low note

were taken on the one and a high note on the other.

Double pipes of unequal length were often

distinguished as male and female, and their piping as gamelion aulema, or married piping.

Phrygian pipes were much in request for funerals and

lamentations. There, again, we have the bassoon principle.

Sophocles refers to a pipe called Elymos,

in his Niobe, and in his Tympanistai,

upon which Athenaeus comments that “we do not understand it to be anything but

the Phrygian, upon which the Alexandrians are very skilful.” Again, Juba says that the Elymoi were an invention of the Phrygians, and that they

were also called Scytalise. This name may have arisen

from their resemblance to staves, or to Laconian snakes, said to be of equal

circumference throughout. J. C. Scaliger says that the Scytalia was a tiny pipe, like a small twig, and of very thin tone. It is to be

regretted that he does not give his authority, for a horn could not be fixed at

the end of a twig, and his description answers better to the Asiatic Gingras

than to the ordinary Phrygian.

Lastly, Julius Pollux says that the Elymos was an invention of the Phrygians, that it was a

double pipe, made of boxwood, with a horn end to each tube, and that it was

employed in the worship of Cybele. The second pipe may have been then used as a

drone. As the two pipes were of boxwood, they would not probably exceed the

diameter of a clarionet, nor the length, on account

of the weight of the material employed. The definition of Julius Pollux agrees

with the former descriptions.

There seems to have been also a stringed instrument

called Elymos; for Apollodorus classes it among them

in his reply to a letter of Aristocles, where he says, “That which we now call Psalterion is the same which was formerly called Magadis; but that which used to be called Klepsiambos (a lyre described as suited for varied metres, and perhaps deriving its name from klepto, to steal, or filch from others,) and the Trigon, and the Elymos, and the Enneachordon, or

nine-string, have fallen into comparative disuse.”

Before parting with the subject of ancient pipes,

there are a few points connected with the manner of playing upon them, and with

pipers, that should be noted. In the first place, we see representations of men

with leathern bands over their mouths, and something of the halter kind over

their cheeks and heads. The bands are stretched tightly over the cheek, and a

hole is cut in the leather to admit the ends of pipes into the mouth, while the

loop over the head seems intended to prevent the strap from slipping below the

cheek. This sort of bandaging was called the Phorbeion;

in Latin, Capistrum. It served to relieve the lip

from the weight of the pipes, but more especially, by its tightness, to

diminish the exertion of contracting the muscles of the mouth, which was

necessary for the production of high Harmonic notes.

In the competitions between ancient pipe-players, it

seems to have been an especial study who should produce the loudest and the

highest notes. A competitor would over-exert his lungs, and overstrain the

muscles of his face, if he could only obtain Harmonic sounds higher than his

fellows. We may smile at their folly in making high notes such an object of

competition, but it is not far different from that of the modem tenor singer,

who, in his endeavour to bring down the applause of

the galleries, will strain his lungs to the very utmost to bring out an ut de poitrine, or high C, from his chest voice.

Some of the Harmonic notes from pipes require great

exertion, and will even bring a flush into the face and forehead, but not so

the fundamental or ordinary notes of the pipes. The following is a player, with

a bandage of this kind, copied from the Arch of Titus.

Another peculiarity was that the players had sometimes

plugs, or stopples, that passed quite through their pipes. The effect of such

plugs might be to shorten the column of air, and so to raise the pitch of the

instrument, or, on the other hand, to close the tube so effectually as to make

a stopped pipe. The capricious forms of some of them are a puzzle that has

hitherto defied explanation, and may continue to do so, until some ancient

treatise on pipe-playing shall be discovered.

The bagpipe had at least the Greek name of Askaulos, but it was very little used by Greeks. The Romans

sometimes gave it this Greek name, and, at others, called it the Tibia utricularis. It is to be considered rather as a Roman

than as a Greek instrument.

Ancient pipes were of so many kinds, that it has

required consideration to place the subject even so far in a digested form

before the reader. Other classes of instruments do not present the same amount

of difficulty. But, before parting with the subject of vibrating reeds, a Fifth

Principle should be mentioned, although we yet lack evidence of any very

ancient use.

In instruments of the clarionet kind we have a single reed that extends over, and flaps against, the sides of

the mouthpiece. That is called the Beating Reed.

CHINESE FREE REED.

The Fifth Principle is the Free Reed that vibrates

without touching anything. The earliest use we know of it is in Chinese organs,

but of these we have no really ancient specimens. Still it is a principle of

considerable interest at the present time, because it is the one upon which

harmoniums are constructed, and we are indebted to the Chinese for all such

instruments. The free reed is now also employed in modern organs. Tongues of

this kind will vibrate, and therefore produce musical sounds, whether they be

made of wood or of metal. If the tongue be large, so as to fit very closely,

and perhaps even to touch the sides of its frame imperceptibly, the tone is

more reedy than with a freer space. Hence the varied qualities that may be

produced from metal reeds made of the same material. Another variation is

caused by superior hardness and closeness of metal.

The Sixth Principle, that of a cup to be blown into by

the mouth, using the lip as a reed, as for Trumpets and Horns, is the same now

as ever. It matters not, except for convenience, whether the instruments be

curved or straight. They all require the lip to be subjected to strong

pressure, the marks of which will often be seen on the player’s mouth. It is

the lip that makes them sound, by its acting as a vibrating reed. Their great

power arises from the bell end.

The ancient trumpet, (Salpinx of the

Greeks, and Tuba of the Romans,) was ordinarily, but not

always, straight, and some were very long. Egyptian trumpets seem to have been

straight, and, in comparison with others, to have been short. Sir J. Gardner

Wilkinson says eighteen inches long. The Assyrian were only rather longer than

the Egyptian. The curved trumpet used by Greeks and Romans was of attributed

Tyrrhenian, otherwise Etruscan, or Tuscan origin. The tubes were of metal,

usually of bronze, and the mouth-pieces of bone. The curvature enabled the Tyrrhenians,

who, according to Aristoxenus, were originally

Greeks, to have more deeply-sounding trumpets, without inordinate length. Some

of the earlier specimens of the straight trumpet, such as one kind of Assyrian,

were cones of gradually increasing circumference, in the style of a postman’s

horn, instead of having only a bellshaped kodon, or mouth. Others, like the Egyptian, had the bell end, as in modem

trumpets; but the Egyptians had also conical trumpets of four feet in length,

without bell ends, and speaking-trumpets of five feet in length, and of large

diameter.

SHELLS FOE HORNS AND TRUMPETS.

A shell of twisted form was used rather as a horn than

as a trumpet, by the Greeks and by the Romans. The Greek name was Kerux, which also signifies a Herald and a Crier,

suggesting that it was originally employed by men holding such offices. The

Latin name of the shell was Buccinum, and

of the trumpet, Buccina. By the Romans it was chiefly, but not

exclusively, used for proclaiming the watches of the day and of the night.

Virgil, and others, refer to the employment of the Buccina in

war, as well as for various other purposes.

When Greece fell under the dominion of the Romans, the

ancient Greek name, Kerux, seems to have been

dropped, and the Greeks to have adopted an imitation of the Latin, calling it Bukane.

We may suppose the original to have been the shell

with which Tritons are represented on ancient gems.

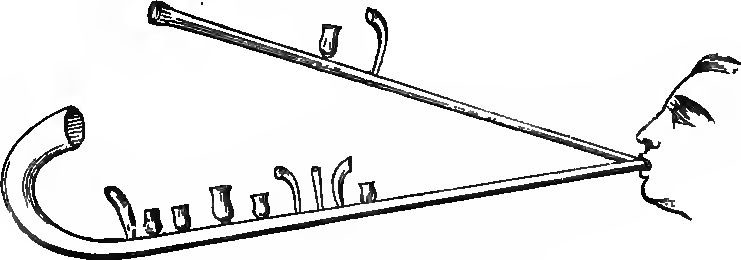

The following cone-shaped pattern was copied from an

antique by Blanchinus, who refers to other such

representations. Another Buccina, of curved form, is given by Dr. Burney as sounded

by a Triton on a frieze, in the court of the Santa Croce Palace at Rome.

Burney made the very natural mistake of supposing this

conch to have been named Tromba Marina by the Italians; but,

oddly enough, they gave that designation to a wooden triangular instrument of

about six feet in height, with but one string, and played with a bow. In fact,

to a Monochord, having nothing whatever of the trumpet, or of the sea about it.

It must not be supposed that the Buccina was always a

shell, or even an imitation of one. The name was transferred to any short

straight trumpet of metal, with a bell-shaped mouth, and so was opposed to the

Salpinx as to size and length, and to the Lituus, as to the latter having a

curved end. For instance, Josephus, in describing the two silver trumpets made

by Moses, says they were little less than a cubit (21 inches) in length, and

scarcely thicker than the reed of a Syrinx; also, that they had bell-ends like

common trumpets. To the long common trumpet he gives the name of Salpinx, and

to the short and small straight trumpet of Moses, Bukane.

THE ROMAN LITUUS.

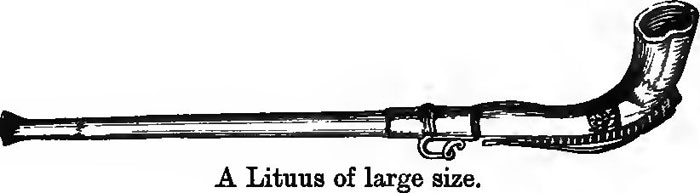

The Lituus was curved upward at the end, and is said

to have taken its name from the bent form of the augural staff. It was a

species of clarion, or Octave-trumpet, made of metal, and of shrill sound The

Romans employed it for their cavalry, and the straight trumpet, for the foot.

Multos castra juvant, et lituo tubae

Permixtus sonitus, bellaque matribus

Detestata.(Horace, Ode i. 1. 23-25.)

The lituus is usually represented as not exceeding two

feet in length, and such were fit for cavalry; but an ancient instrument was

found, among other Roman antiquities, in the bed of the river Witham, in

Lincolnshire, in 1761, and this had the form of the Lituus, but exceeded four

feet in length. The following is a reduced copy of it, from Burney’s History,

included in plate 4 of vol. 1. The instrument was then in the possession of Sir

Joseph Banks, and Burney says was of very thin brass, and had been well gilt.

As the mixture of copper and zinc, to make brass, seems to have been unknown to

the ancients, I suspect that for brass we should read bronze.

Horns, straight and twisted, may be so readily

imagined that there is nothing more to be said about them than that they were

at first, literally, horns of animals, and that these were afterwards imitated

in metal. In the first case, they had every variety of Nature’s forms, but when

made in metal, they were usually curved throughout their entire length, instead

of only at the end, as was the Lituus.

CHAPTER XI

And now, as to Instruments of Percussion.

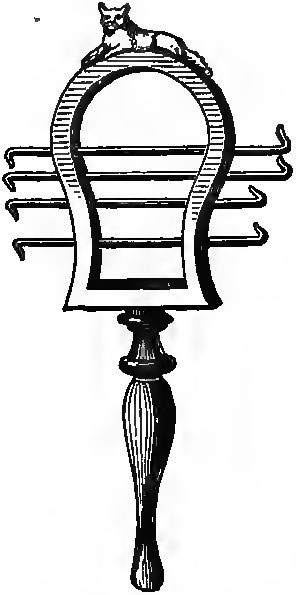

Among these, the Sistrum has some claim to be first

named, on account of its having been employed in Egyptian temples, and for

religious purposes exclusively. It consisted of a thin oval hoop of metal,

fixed at the lower end into a handle, and the handle was visually of metal

also. The hoop was pierced with holes at equal distances on both sides, and in

these holes were three or four loose metal bars, which were all to be shaken at

one time, by a light jerk from the hand, and this made them rattle. The bars

were like the stems of thin fire-pokers, but they were bent at the ends, to

prevent their falling out of their places. It was so great a privilege, says

Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson, to hold the sacred Sistrum in the temple, that it was

given to queens, and to those noble ladies who had the distinguished title of women

of Amun, and who were devoted to the service of the deity. The Egyptian Amun

was the Jupiter Ammon of the Romans. Again, Sir Gardner says, The Sistrum was

the sacred instrument par excellence, and

belonged as peculiarly to the service of the temple, as the small tinkling bell

to that of the Roman Catholic chapel. Some pretend it was used to frighten away

Typhon, (the Evil Being), and the rattling noise of its movable bars was

sometimes increased by the addition of several loose rings. It had generally

three, rarely four, bars; and the whole instrument was from 8 to 16 or 18

inches in length, entirely of brass or bronze. It was sometimes inlaid with

silver, or gilt, or otherwise ornamented; and being held upright, was shaken,

the rings moving to and fro upon the bars. These last

were frequently made to imitate the sacred asp, or were simply bent at each end

to secure them. Plutarch mentions a cat with a human face on the top of the

instrument, and at the upper part of the handle, beneath the bars, the face of

Isis on the one side, and of Nephtys on the other,

[signifying the beginning and the end.]

The British Museum possesses an excellent specimen of

the Sistrum, well preserved, and of the best period of Egyptian art. It is one

foot four inches high, and had three movable bars, which have been

unfortunately lost. On the upper part are represented the goddess Pasht, or Bubastis, [the Greek Diana,] the sacred vulture,

and other emblems; and on the side below is the figure of a female, holding in

each hand one of these instruments.

The handle is cylindrical, and surmounted by the

double face of Athor, [the Venus of Egypt,] wearing an asp-formed

crown, on whose summit appears to have been the cat, now scarcely traced in the

remains of its feet.

Dr. Burney exhibits a perfect specimen of a Sistrum

with the cat upon it, copied from one in the library of Genevieve at Paris,

which is here reproduced.

The following is a translation of Plutarch’s account

of the Sistrum, in his treatise on Isis and Osiris.

It shows why this instrument of religion was carried

only by married women, and the signification of the cat as an emblem. Isis was

the supposed enemy to Typhon, and Osiris was the supposed judge of An Egyptian

Sistrum. the dead:

The Sistrum likewise indicates that it is necessary

that beings should be agitated, and never cease to rest from their local

motion, but should be excited and shaken when they become drowsy and languid.

For they say that Typhon is deterred and repelled by the Sistra; manifesting by

this, that as corruption binds and stops, [the course of things] so generation

again resolves nature, and excites it through motion. But, as the upper part of

the Sistrum is convex, so the concavity of it comprehends the four things that

are agitated. For the general and corruptible portion of the world is

comprehended indeed by the lunar sphere; but all things are moved and changed

in this sphere through the four elements of fire and earth, water and air. And

on the summit of the concavity of the Sistrum, they carved a cat, having a

human face ; and on the under part, below the rattling rods, they placed on one

side the face of Isis, and on the other that of Nephtys,

obscurely signifying by their faces generation and death (or corruption); for

these are the mutations and motions of the elements. But by the cat they

indicated the moon, on account of the diversity of colours,

operation by night, and fecundity of this animal. For it is said that she

brings forth one, afterwards two, three, four, and five kittens, and so adds

till she has brought forth seven; so that she brings forth twenty-eight in all,

which is the number of illuminations of the moon. This, therefore, is perhaps

more mythologically asserted. The pupils, however, in the eyes of the cat are

seen to become full and to be dilated when the moon is full, and to be

diminished and deprived of light during the decrease of this star.

However debased were many of the superstitions of the

ancient Egyptians, as to the supposed emblems of their gods, there was some

part of their philosophy in which they were in advance of other heathens; and,

so far as knowing the true form of the earth, they were in advance of the heads

of the Roman Church to within the present century.

The Egyptians worshipped Osiris as the sun, and Isis

as the moon; and when Manetho, the Egyptian priest, states their emblems, he

adds: Statues and holy places are prepared for them, but the true form

of God is unknown. The world had a beginning, and is perishable it is in the shape of a ball. The stars are fire, and earthly things are under their influence. The

moon is eclipsed when it crosses the shadow of the earth. The soul endures, and

passes into other bodies. The rain is caused by a change in the

atmosphere.

There are many points of resemblance between the

Egyptians and Christians which might interest the curious, but they are beyond

the scope of the present work. I will only name one which I do not recollect to

have seen noticed, and that one, only because it is included in a book to which

few would think of referring upon such a subject. It is as to sprinkling with

water those who enter the temples, to purify them. Vessels of water were kept

at the entrances of Egyptian temples for that special purpose. As to the

Sistrum, according to Bruce, the Abyssinian Christians retain it in use in

their worship, instead of little bells; and one of triangular form, with rings

on its bars, seems to have been used in Italy at the time of child-birth as

late as the sixteenth century.

THE ASSYRIAN DULCIMER.

The Assyrians had an instrument with bars of metal

such as those of the Sistrum, but, instead of being straight and loose, they

were fastened into a long shallow box as a sound-board, and bent to curves of

different heights, so that they might with greater ease be struck separately by

a rod of metal held in the right hand. This instrument approaches more to the

class of dulcimer than to any other. Its Assyrian name is unknown, and although

a recent writer has proposed for it the Hebrew one of Asor, I prefer that of

Assyrian dulcimer, because the Hebrew word Asor has no such meaning as a

musical instrument, but is simply the numeral ten. This will be seen in the

sequel, under the Hebrew instruments, where the question is fully discussed.

The Egyptians had instruments of the same class as the

above, but they played them by pulling the wires. In one case the two ends were

fixed, and in the other one end of the wire rods was left free.

These instruments must have been for the purpose of

obtaining Harmonic sounds from vibrating rods, just as now exemplified in

lectures on sound. The Egyptian instruments are curious anticipations of

supposed modern discoveries.

The large drums of the Egyptians were shaped like wide

barrels, about two feet and a half high and two feet broad, and were beaten at

the ends by drum-sticks covered with leather pads. The drum-heads of skin or of

leather were ingeniously tightened by strings, as in some modem drums. The

Egyptians had likewise small drums, which were in the proportion of three or

four degrees of length to one of diameter. These, also, had a wider

circumference in the middle than at the extremes, and were hung from the neck to

a little below the waist of the player, so as to be conveniently tapped at the

ends by the fingers. The modern Hindoos use a drum of

this kind. The Egyptians had timbrels or tambourines, both round and

quadrilateral; also cymbals of various sizes; and clappers, or short maces, to

be sounded by being knocked together.

The quadrilateral tambourines were sometimes divided

into two by a bar, so that one end might be tuned to a different note, possibly

to a Fifth above the other. They do not seem to have added bells, or tiny

cymbals, to tambourines, as did the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

CYMBALS AND CLAPPERS OF VARIOUS KINDS.

The Greeks had, at least, three kinds of cymbals.

First, the Kumbala, which appear to have been the

largest, and of metal; next, the Lekidoi, which,

judging from their name, were perhaps the oval dish-cover shaped metal cymbals

with bandies, of which kind we see so many in the hands of dancing nymphs; and,

thirdly, the Oxubapha, or Oxubaphoi.

The last were named after the Greek vinegar saucers, and were therefore of

diminutive size. They were perhaps such as were suspended in the frames of

their timbrels or tambourines. The Romans had large cymbals like the Greeks,

and used them specially for festivals. They had also the same small metal

cymbals, which they named, from their silver vinegar cups, Acetabula.

According to Clemens Alexandrinus,

cymbals were the war-instruments of the Arabs. Cymbals, says St. Augustine, are

compared by some to our lips, because they sound by touching one another.

The short Egyptian maces, for clappers, were called by

the Greeks Krotala, and were especially used in the

imported worship of the mother goddess, Cybele. The Krotala were either hinged, or had a weak spring, midway between the two heads or

knockers, so that they could be bent towards one another. They flew apart by

the opening of the hand, and clapped together when it was shut. Sometimes the Krotala were made wholly of wood, or of a split reed, with

something to clash at the two ends.

These latter forms are found among the Romans, under

the Latinized Greek name, Crotala. Publius Syrus, in

his Sententiae, calls the stork crotalistria,

on account of the noise made by the bird in striking together the two bones of

its beak.

All nations have had castanets of some kind. Their

origin has been debated between nut shells on the one hand, and cockle or

oyster shells on the other. Climate and the character of the country had more

to do with the use of either than any thought of invention. The Greek name for

the castanets used to accompany dancing was Krembala.

And beating down the limpets from the rocks, they made a noise like castanets. They were sometimes made of metal, and gilt.

The principle of ancient instruments of percussion has

been so entirely the same in all ages, and in all districts, that there is

scarcely a difference between them worthy of note. They marked rhythm, but had

little else to do, either with the art or with the science of music, and the

only thing now required is to be able to recognise them under their various names.

------------------------------------------------- -----------------------

Dr. Burney exhibits

a perfect specimen of a Sistrum with the cat upon it, copied from

one in the library of Genevieve at Paris, which is here reproduced. The following is

a translation of Plutarch�s account of the Sistrum, in his treatise

on Isis and Osiris. It shows why this

instrument of religion was carried only by married women, and the

signification of the cat as an emblem. Isis was the supposed enemy

to Typhon, and Osiris was the supposed judge of An Egyptian Sistrum.

the dead:� �The Sistrum likewise

indicates that it is necessary that beings should be agitated, and

never cease to rest from their local motion, but should be excited

and shaken when they become drowsy and languid. For they say that

Typhon is deterred and repelled by the Sistra; manifesting by this,

that as corruption binds and stops�, [the course of things] so generation

again resolves nature, and excites it through motion. But, as the

upper part of the Sistrum is convex, so the concavity of it comprehends

the four things that are agitated. For the general and corruptible

portion of the world is comprehended indeed by the lunar sphere;

but all things are moved and changed in this sphere through the

four elements of fire and earth, water and air. And on the summit

of the concavity of the Sistrum, they carved a cat, having a human

face ; and on the under part, below the rattling rods, they placed

on one side the face of Isis, and on the other that of Nephtys,

obscurely signifying by their faces generation and death (or corruption);

for these are the mutations and motions of the elements. But by

the cat they indicated the moon, on account of the diversity of

colours, operation by night, and fecundity of this animal. For it

is said that she brings forth one, afterwards two, three, four,

and five kittens, and so adds till she has brought forth seven;

so that she brings forth twenty-eight in all, which is the number

of illuminations of the moon. This, therefore, is perhaps more mythologically

asserted. The pupils, however, in the eyes of the cat are seen to

become full and to be dilated when the moon is full, and to be diminished

and deprived of light during the decrease of this star.� However debased were

many of the superstitions of the ancient Egyptians, as to the supposed

emblems of their gods, there was some part of their philosophy in

which they were in advance of other heathens; and, so far as knowing

the true form of the earth, they were in advance of the heads of

the Roman Church to within the present century. The Egyptians worshipped

Osiris as the sun, and Isis as the moon; and when Manetho, the Egyptian

priest, states their emblems, he adds, �Statues and holy places

are prepared for them, but the true form of God is unknown.

The world had a beginning, and is perishable�it is in the shape

of a ball. The stars are fire, and earthly things are under

their influence. The moon is eclipsed when it crosses the

shadow of the earth. The soul endures, and passes into

other bodies. The rain is caused by a change in the atmosphere�. There are many points

of resemblance between the Egyptians and Christians which might

interest the curious, but they are beyond the scope of the present

work. I will only name one which I do not recollect to have seen

noticed, and that one, only because it is included in a book to

which few would think of referring upon such a subject. It is as

to sprinkling with water those who enter the temples, to purify

them. Vessels of water were kept at the entrances of Egyptian temples

for that special purpose. As to the Sistrum, according to Bruce,

the Abyssinian Christians retain it in use in their worship, instead

of little bells; and one of triangular form, with rings on its bars,

seems to have been used in Italy at the time of child-birth as late

as the sixteenth century. THE ASSYRIAN DULCIMER.

The Assyrians had

an instrument with bars of metal such as those of the Sistrum, but,

instead of being straight and loose, they were fastened into a long

shallow box as a sound-board, and bent to curves of different heights,

so that they might with greater ease be struck separately by a rod

of metal held in the right hand. This instrument approaches more

to the class of dulcimer than to any other. Its Assyrian name is

unknown, and although a recent writer has proposed for it the Hebrew

one of Asor, I prefer that of Assyrian dulcimer, because the Hebrew

word �Asor� has no such meaning as �a musical instrument�, but is

simply the numeral �ten�. This will be seen in the sequel, under

the Hebrew instruments, where the question is fully discussed. The Egyptians had

instruments of the same class as the above, but they played them

by pulling the wires. In one case the two ends were fixed, and in

the other one end of the wire rods was left free. These instruments

must have been for the purpose of obtaining Harmonic sounds from

vibrating rods, just as now exemplified in lectures on sound. The

Egyptian instruments are curious anticipations of supposed modern

discoveries. The large drums of

the Egyptians were shaped like wide barrels, about two feet and

a half high and two feet broad, and were beaten at the ends by drum-sticks

covered with leather pads. The drum-heads of skin or of leather

were ingeniously tightened by strings, as in some modem drums. The

Egyptians had likewise small drums, which were in the proportion

of three or four degrees of length to one of diameter. These, also,

had a wider circumference in the middle than at the extremes, and

were hung from the neck to a little below the waist of the player,

so as to be conveniently tapped at the ends by the fingers. The

modern Hindoos use a drum of this kind. The Egyptians had timbrels

or tambourines, both round and quadrilateral; also cymbals of various

sizes; and clappers, or short maces, to be sounded by being knocked

together. The quadrilateral

tambourines were sometimes divided into two by a bar, so that one

end might be tuned to a different note, possibly to a Fifth above

the other. They do not seem to have added bells, or tiny cymbals,

to tambourines, as did the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. CYMBALS AND CLAPPERS

OF VARIOUS KINDS.

The Greeks had, at

least, three kinds of cymbals. First, the Kumbala, which appear

to have been the largest, and of metal; next, the Lekidoi, which,

judging from their name, were perhaps the oval dish-cover shaped

metal cymbals with bandies, of which kind we see so many in the

hands of dancing nymphs; and, thirdly, the Oxubapha, or Oxubaphoi.

The last were named after the Greek vinegar saucers, and were therefore

of diminutive size. They were perhaps such as were suspended in

the frames of their timbrels or tambourines. The Romans had large

cymbals like the Greeks, and used them specially for festivals.

They had also the same small metal cymbals, which they named, from

their silver vinegar cups, Acetabula. According to Clemens

Alexandrinus, cymbals were the war-instruments of the Arabs. �Cymbals,�

says St. Augustine, �are compared by some to our lips, because they

sound by touching one another.� The short Egyptian

maces, for clappers, were called by the Greeks Krotala, and were

especially used in the imported worship of the mother goddess, Cybele.

The Krotala were either hinged, or had a weak spring, midway between

the two heads or knockers, so that they could be bent towards one

another. They flew apart by the opening of the hand, and clapped

together when it was shut. Sometimes the Krotala were made wholly

of wood, or of a split reed, with something to clash at the two

ends. These latter forms

are found among the Romans, under the Latinized Greek name, Crotala.

Publius Syrus, in his Sententiae, calls the stork crotalistria,

on account of the noise made by the bird in striking together the

two bones of its beak. All nations have

had castanets of some kind. Their origin has been debated between

nut shells on the one hand, and cockle or oyster shells on the other.

Climate and the character of the country had more to do with the

use of either than any thought of invention. The Greek name for

the castanets used to accompany dancing was Krembala. �And beating

down the limpets from the rocks, they made a noise like castanets.� They

were sometimes made of metal, and gilt. The principle of

ancient instruments of percussion has been so entirely the same

in all ages, and in all districts, that there is scarcely a difference

between them worthy of note. They marked rhythm, but had little

else to do, either with the art or with the science of music, and

the only thing now required is to be able to recognise them under

their various names.

STRINGED INSTRUMENTS

12.-

Stringed instruments.—The four grades of Lyre.—Phorminx,

Kithara, and Chelys.—Polyphthongos, Polychordos, Barbitos,

or Asiatic Lyre.—Sambuca, or small Trigon.—Etruscan Lyre.

—The fabulous Tripod of Pythagoras.—Apollo an ill-used

god. —The Pektis.—Nabla.—Pandoura. — Skindapsos. — Pelex.—

Greeks no originators of new principles in instruments.—

Appendages of the Lyre.—Psaltery a class of Harp—Large

Trigon.—Psalmos.—No wire strings.—Epigoneion and Simikion

real Harps. — Egyptian Harps of various kinds. — Etruscan

imagination.—Bands of blind men.—Roman use of four strings.

—Boethius an indifferent authority upon music.

|