|

The abdication of Napoleon, his retirement from

Paris to Malmaison, and his flight to Rochefort, have been related in a

previous chapter. When Napoleon arrived at that port (July 3,1815), he found the

coast narrowly watched by British sail, and hazard upon every side. For ten

days he waited to balance chances, conscious of a certain loss of elasticity in

himself, listening to the counsels of others, himself indifferent. A

clandestine escape, an ignominious capture in the ballast of a Danish sloop or

in an open row-boat, would have been inconsistent with an impressive close;

and, after some hesitation, he rejected all desperate expedients and determined

to throw himself on the generosity of the English people. On July 13 he wrote

to the Prince Regent that he had terminated his political career, and that he

came, like Themistocles, to seat himself at the hearth of the British nation

and to claim the protection of her laws. Two days later he gave himself into

the charge of Captain Maitland of the Bellerophon. He knew well that he

could expect little mercy from the restored Government of France, and that the

Prussians would shoot him like a dog. But England was the refuge of the

homeless and the asylum of the exile. She had sheltered Paoli, the friend of

his youth; she had sheltered the Bourbons, the rivals of his manhood. Out of

magnanimity she might shelter him.

But the man whose ambition had wrought such disasters

could not expect to be treated with leniency; and the British Government

determined that Napoleon was no guest, but a prisoner of war. It was a case of

policy, not of precedents; and, even if Lord Liverpool’s Cabinet had been

accessible to quixotic impulses, it would have been their plain duty to

suppress them in the interests of European peace. The Congress of Vienna had

declared Napoleon to be an outlaw, and, in virtue of a Convention struck on

August 2, 1815, the four Great Powers agreed to regard him as their common

prisoner. The turn of events had devolved upon Great Britain the ungracious

office of the gaoler; but Austria, Russia, and

Prussia were consenting parties; and all four Powers promised to name

commissioners to assure themselves of Napoleon’s presence in the

place of his captivity. Meanwhile, on July 28, the British Government had

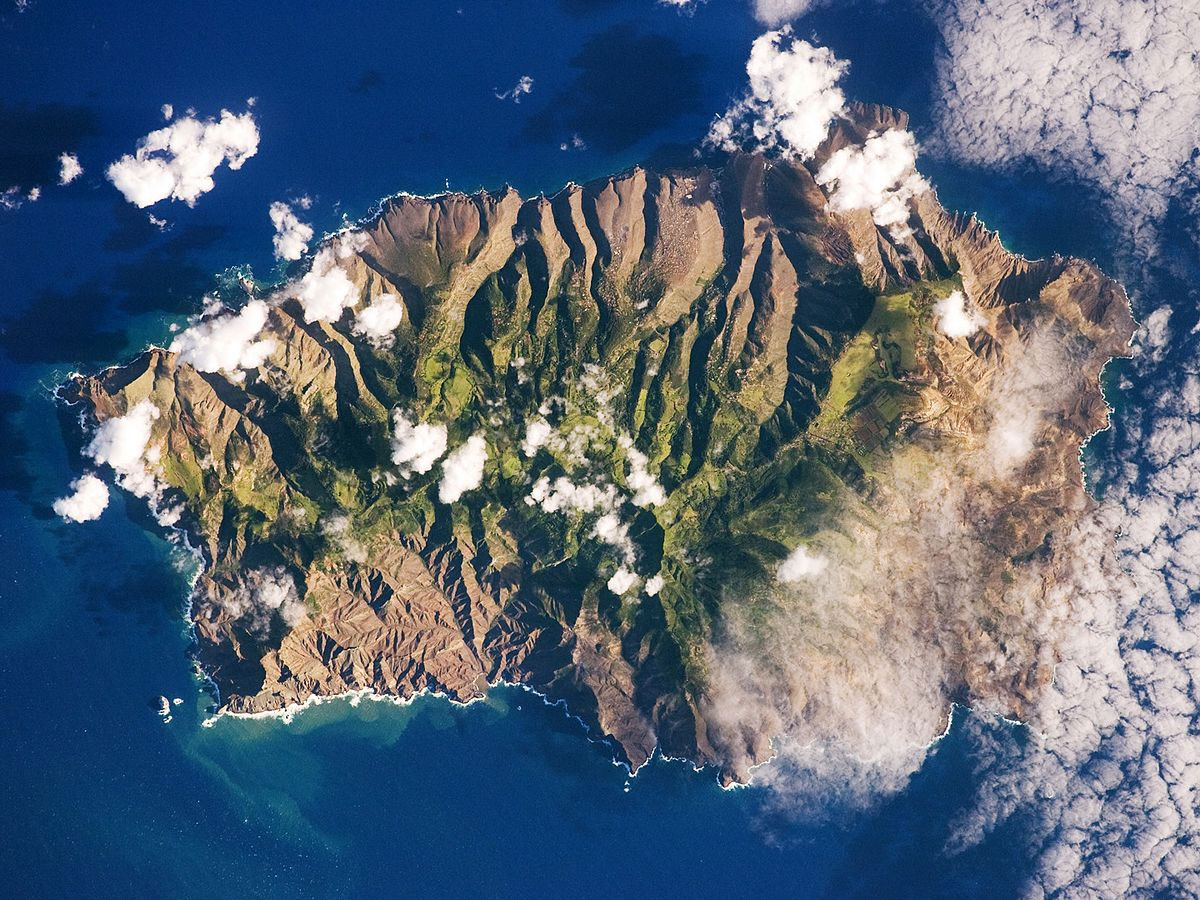

decided to send their captive to St Helena. In that lonely island of the

Atlantic, with its precipitous coast, its scanty harbourage,

its sparse population, the great prisoner of state might be securely guarded,

the more so as the East India Company, to whom the island belonged, had

recently erected upon it a complete system of semaphores. The climate was

reported to be salubrious; and in St Helena Napoleon might enjoy a larger

measure of liberty than any government would then have been prepared to concede

to him in Europe. It was a hard fate, but brighter than an Austrian fortress,

and gentler than the doom of Murat and of Ney.

On August 7 he was removed to H.M.S. Northumberland, which, under the command of Admiral Sir George Cockbum,

was instructed to convey him to his destination. His suite consisted of

twenty-five persons, including Count Montholon and

General Gourgaud, who had served as adjutants in the

last campaign; General Bertrand, who had controlled his household in Elba;

Count de Las Cases, once a royal emigre, now one of the most attached of

his adherents; and Dr Barry O’Meara, the surgeon of the Bellerophon, who,

at Napoleon’s request and with the consent of the British Government, was

allowed to act as his medical attendant. Montholon and Bertrand were accompanied by their wives, Las Cases by his son. On October

17, at the hour of eight in the evening, after a passage of ninety-five days,

Napoleon landed at Jamestown. As the house destined for his reception was not

yet ready, he took up his residence at the Briars, a villa belonging to a

merchant named Balecombe, where he spent some weeks

in pleasant and familiar intercourse with the family of his host. In December

the exiles moved into Longwood, a low wooden building on the wind-swept

plateau, far above the prying curiosity of the port. It was here that the last

scene in Napoleon’s life-drama was enacted.

For the general history of Europe the captivity at St

Helena possesses a double interest. Not only did it invest the career of the

fallen hero with an atmosphere of martyrdom and pathos which gave to it a new

and distinct appeal, but it enabled him to arrange a pose before the mirror of

history, to soften away all that had been ungracious and hard and violent, and

to draw in firm and authoritative outline a picture of his splendid

achievements and liberal designs. The Napoleonic legend has been a force in the

politics of Europe; and the legend owes much to the artifice of the exiles. The

great captain, hero of adventures wondrous as the Arabian Nights, passes over

the mysterious ocean to his lonely island and emerges transfigured as in some

ennobling mirage. He shares the agonies of Prometheus, benefactor of humanity,

chained to his solitary rock; his spirit is with Marcus Aurelius, moving in the

serene orbit of humane and beneficent wisdom. The seed sown from St Helena fell

upon fruitful soil and was tended by devout hands.

Carrel, the great Liberal journalist of the July

monarchy, claims Napoleon, on the ground of the Longwood conversations, as the

friend of the Republic which he overturned. Quinet sings of him as of some vague

and romantic embodiment of the democratic spirit:

“J’ai couronné le peuple en France, en Allemagne;

Je I'ai fait gentilhomme autant que

Charlemagne ;

J'ai donnédes aïeux a la foule sans nom;

Des nations partout fai gravé le blason.”

The heir of the Napoleonic House, Louis Bonaparte, son

of the ex-King of Holland, knew well how to exploit the democratic elements in

his uncle’s career. In 1831 he was secretly negotiating with Republican leaders

in Paris; in 1832 he published a statement in his Reveries politiques that his principles were “entirely republican.” In 1839 a slender volume came

from the same pen, entitled Idées Napoleoniennes, which contained the whole essence of

the exilic literature and the whole programme of the

liberal Empire. The Siècle, a Bonapartist organ, spoke in 1840 of “the

sublime agony of St Helena, longer than the agony of Christ, and no less

resigned”; and in the haze of sentiment men lost sight of the elementary facts

of Napoleon’s career. “The thought of Napoleon at St Helena,” say the editors

of the official Correspondence (vol. xxix), “is a thought of

emancipation for humanity, of democratic progress, of the application of the

great principles of the Revolution”; and this was the pretext and apology for

the Second Empire, the Government which, beginning with a cannonade in the

Boulevards, ended with the capitulation of Sedan and the loss of Alsace and

Lorraine.

Exile is in itself a form of martyrdom; and the exiles

of Longwood ate their bread in genuine sorrow. As Las Cases remarked, “ The

details of St Helena are unimportant; to be there at all is the great

grievance.” A little company of French gentlemen and ladies, accustomed to the

stirring life of a brilliant capital, found itself pitched on a desolate

island, far from friends and home and all the great movement of the world. The

attendants of Napoleon were not cast in the stoical mould; and, even if considerations of policy had not been involved, temperament

would have inclined them to exaggerate minor discomforts, to strain against the

restrictions of the governor, to shudder at the rocks and ravines, to condemn

the rain when it was rainy, the sun when it was sunny, and the wind when it was

windy, to compare the sparse gum-trees of the Longwood plateau with the ample shades

of Marly and St Cloud, and the rough accommodation of the Longwood house with

the comforts of a well-appointed Parisian hotel. To a man like Napoleon, whose

whole soul was in politics, seclusion was a kind of torture. He had no

administrative occupations to absorb his energies as had been the case in Elba;

and “time,” to quote his own bitter phrase, was now “his only superfluity.” To

quicken all the leaden hours was a task too heavy even for his busy genius. He

learnt a little English, he dictated memoirs, he played chess, he read books

and newspapers, he set Gourgaud mathematical

problems, and in the later half of 1819 and the

earlier half of 1820 he found some solace in gardening. In the first two years

of his captivity his spirits were sometimes high and even exuberant; and in the

exercise of his splendid intellect he must have found some genuine enjoyment.

But at heart he was miserable, spiting himself like a cross child, and allowing

petty insults to fester within him. Now he was calm, proud, and grand, now

irritable and wayward. Even the approach of death could not purge his soul of

its evil humours, and he left a legacy to Cantillon

as a reward for attempting to assassinate the Duke of Wellington.

The colony of Longwood had a political object in

magnifying the hardships of its position; and it has left a large literature

of complaint. “Our situation here,” said Napoleon, as reported by Las Cases, “may even have its attractions. The universe is looking at us. We remain the

martyrs of an immortal cause. Millions of men weep for us; our country sighs;

and glory is in mourning. Adversity was wanting to my career. If I had died on

the throne amid the clouds of my omnipotence I should have remained a problem

to many men; today, thanks to my misfortune, they can judge of me naked as I

am.” Nor was this the only advantage that might be reaped from the policy of

complaint. Compassionate Whigs in England, learning the tale of hardships, the

bad food, the damp house, the intercepted letters, the ostentatious cordon of

sentinels, would rise and denounce the Government in Parliament. At the voice

of Lord Holland the heart of the country would be stirred; and Napoleon would

be summoned back to Europe on the crest of the Whig reaction. Even if this hope

failed, still it would be wise to disparage the good name of England. The

Bourbons owed everything to Great Britain, but the rivalry between France and

England was older than the Bourbons; and the story of petty indignities heaped

upon her greatest captain by a British Government would be accepted in France

as a token that he too had suffered for the old cause, and that his dynasty

would never forget it.

Holding the general conviction that Napoleon was far

too dangerous to be allowed abroad, and having some reason to believe that

plots were on foot to effect his rescue, Lord Liverpool’s Cabinet properly

determined to keep a close watch on St Helena. Their precautions may have been

excessive—and excessive the Duke of Wellington thought them—their suspicions

over-done, their regulations too minute and harassing. Obtuse the Government

undoubtedly was, but it was as humane and considerate as its sense of duty

would permit. The prisoner received a yearly allowance of £8,000, subsequently

raised to £12,000, inhabited the second-best house in the island, was permitted

to retain a numerous suite and to move freely without an escort within a

circuit of twelve miles. He might gratify his taste for books and newspapers

and music, and he might ride or walk outside the radius with a British officer

in attendance.

These are not the provisions of an inhuman Government;

and the man who was sent out to administer them was not inhuman. Sir Hudson

Lowe, who assumed sole charge of the island on April 14, 1816, was an officer

with a respectable record, though not one which would be likely to commend him

to Napoleon. He had led a regiment of Corsican rangers, participated in the

siege of Toulon, and brought the news of Napoleon’s abdication to London. In

five stormy interviews, all held within the first four months of Lowe’s

arrival, Napoleon poured out the vials of his wrath upon the luckless governor,

whose chief crimes consisted in his refusal to extend the twelve miles’ limit

or to forward a letter of complaint to the Prince Regent save through the

ordinary ministerial channels. After this, Napoleon never suffered the “Sicilian thief-taker” to approach him, or attempted to revise his first and

hasty estimate. It may be conceded that Lowe was a martinet, that he was

deficient in graciousness and tact, and that he ultimately came to suffer from

a mania of suspicion. To be a good regimental officer is one thing, to

discharge a delicate political mission is another. Lowe was full of loyal

punctilio, the home Government, with almost incredible pedantry, had insisted

that Napoleon should be refused the Imperial title and known only by the

designation of General Bonaparte. A wise governor would have taken good care to minimise the effect of so stupid a regulation as soon

as he had ascertained that it was violently objected to. Lowe on the other hand

administered the rule with military exactitude. He intercepted a book from

Europe because it was directed to “the Emperor,” and recommended the officers

of the 20th regiment to decline a copy of Coxe’s life of Marlborough presented to them by Napoleon during his last illness

because it contained the Imperial name on the title-page. So wondrous an

exhibition of obtuse literalism has rarely been afforded. But there was no

inhumanity in Lowe. He was genuinely solicitous for the creature comforts of

the exiles.

It was, however, part of the policy of Longwood to

court martyrdom and to advertise woes. When Napoleon failed to obtain a

relaxation of the twelve miles’ limit, he declared that he would not ride out

at all; when he was reminded of the need of economy, he ordered his plate to be

broken up, as if the wicked gaoler had driven him to

starvation’s brink. On October 9, 1816, some new and more stringent regulations

arrived from England, which had probably been suggested by intelligence

received in London in the previous August, to the effect that three hundred men

had set sail from Baltimore to attempt a rescue. The limit was contracted to

eight miles, and the sentinels were drawn in close to the house at sunset, so

that the exiles were deprived of the full enjoyment of the coolest and most

delicious hours of the day. The new restrictions (which were subsequently

relaxed) were certainly unpleasant; and it is not surprising that they should

have provoked a protest.

In 1817 a thin volume was published in London entitled Letters from, the Cape of Good Hope in reply to Mr Warden. The letters, which purported to be written by an Englishman, were

in reality translated from the French; and the original draft was secretly

dictated by Napoleon to Las Cases. They were designed to impress the British

public with the sufferings of the exiles, and to furnish a defence for those episodes in Napoleon’s career which had proved most repugnant to

British opinion—the execution of the Duc d’Enghien,

the death of Captain Wright, the treatment of the Spanish Bourbons, and the

return from Elba. It was represented that the new code of rules was worthy of

Botany Bay; that Napoleon could not go out into his garden without being spied

on by a red-coat; that he was not allowed even to exchange a word with a

native; that the climate of St Helena was fatal to health, and the food

mediocre; that for many months Napoleon had not left his four ill-built,

unwholesome little rooms; and that the British Government was incurring a cost

of £20,000 a year to keep a prisoner within four walls under a tropical sun.

It was a skilful demonstration, but the Tory garrison

showed no sign of distress, and the Quarterly blew its loudest note of

defiance. At the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (November 21,1818) the

representatives of Russia, Austria, and Prussia formally testified their

approval of the new regulations.

The Emperor’s autobiography had been commenced at the

Tuileries and St Cloud, where he had dictated accounts of several of his

Italian battles to General Bertrand and given orders that plans and maps should

be drawn to illustrate his Italian and Egyptian campaigns. 'Hie work was

resumed at St Helena with such materials as the Emperor was able to gather

round him; and the story of Brumaire and the Provisional Consulate, of the

early exploits in Italy, Egypt, and Syria, of the return from Elba and the

Hundred Days, was written in a connected form at Napoleon’s dictation, together

with a critical account of the Hohenlinden and Waterloo campaigns. Chapters

were added upon the rights of neutrals, the battle of Copenhagen, and the

assassination of Paul I. Four notes were dictated on Lacroix’s Memoires pour

server a l’histoire de Saint Domingue, and six

notes on de Pradt’s Les Quatres Concordats; but,

with the single exception of Waterloo, no unlucky campaign was recorded, and

the account of Waterloo was not a record but an apology. For a moment, in 1817,

Napoleon seems to have contemplated a narrative of the Russian expedition; but

the plan was soon dropped for lack of materials, and a projected history of the

Revolutionary Convention shared the same fate. The choice of episodes was not

fortuitous. The Memoires were designed to exhibit Napoleon as the soldier

of the Republic, and to clear his military reputation from the stain of his

last resounding defeat.

Sainte-Beuve, the finest of critics, has recognised the literary quality of the St Helena writings,

the prompt imperious brevity, the exquisite clearness, the occasional beauties

of sentiment and eloquence. It is natural to compare the record of the Egyptian

and Syrian campaigns, where Napoleon depicts himself at once as soldier,

statesman, and discoverer, with another splendid fragment of military autobiography,

the Commentaries of the Gallic War. The two stories have the same

lucidity, the same gift of perspective, the same command of professional

technique, the same wide scope of observation, the same close adherence to

detail. Caesar has more formal eloquence; Napoleon has more romance, more

passion, more vibration. But, while each wrote to defend his policy and his

military reputation, Caesar had no interest in concealing or confusing the

truth.

Yet the formal memoirs, however strongly conceived and

carefully executed, are the least interesting portion of the St Helena

retrospect. Napoleon was a voluble talker; and, when the long tension of his

political career was relaxed, his restless mind poured itself out upon all the

incidents of his wonderful life. It is true that he desired a certain reading

of his career to be accepted, and that he more than once prompted his faithful

followers to record his remarks; but he was far too mobile to maintain a steady

pose. He was not a chilly man sitting down to falsify a dull life, but a child

of nature, frank, passionate, impetuous, full of sudden turns and ruses which

carried him far beyond the boundaries of his set apology. The schemer’s mind,

constant to its old habit, schemes for the past, as it had formerly schemed for

the future; and we cannot tell whether the plans which he attributes to himself

had actually been in his mind. A man of such a temperament could talk neither

sober autobiography nor sustained deceit. And so, side by side with the

official legend, the Moniteur of exile,

deferential to a moral judgment whose power it uneasily apprehends but never

understands, we have the fragments of spontaneous talk, sometimes shrewd and

lively, sometimes grand and eloquent, sometimes brutal, sometimes kindly,

always and through every mood vivid and unmistakable.

Napoleon shrewdly saw that the forces of reaction were

spreading over Europe, and that the yoke of the Bourbons would soon become

intolerable to France. Some day the King of Rome

would have his chance. In the sombre gloom of

clericalism and privilege and military impotence, men would point back to the

bright vision of a Liberal Empire, which had been based on social equality and

religious tolerance, which had made France the arbitress of Europe, and Paris

the centre of European civilisation.

Then France would turn to her great, calm, and beneficent Prometheus, would

gather his lightest words and descry his true intentions. She would learn that

he alone had understood and adored her; that he loved peace, but was driven by

wicked foreigners into ceaseless war; that, although he had showered golden

gifts upon her, his cornucopia was still full of the manifold blessings of

prosperity and constitutional rule which he intended to bestow upon Europe

after the conclusion of a general peace. She would read his own authentic

accounts of campaigns which he had fought as the soldier of the Republic, and,

perusing his story of Waterloo, would recover faith in his supreme mastery of

war.

“The system of government,” said Napoleon once to O’Meara, must be adapted to the national

temperament and to circumstances. In the first place France required a strong

government. While I was at the head of it, I may say that France was in the

same condition as Rome when a dictator was declared necessary for the salvation

of the Republic. A series of coalitions against her existence was formed by

your gold amongst all the powerful nations of Europe. To resist successfully,

it was necessary that all the energies of the country should be at the disposal

of the chief. I never conquered unless in my own defence.

Europe never ceased to make war upon France and her principles. We had to

strike down others or to be ourselves struck down. Between the parties that so

long agitated France I was like a rider seated on an unruly horse, who always

wanted to swerve either to the right or to the left; and to make him keep a

straight course I was obliged to let him feel the bridle occasionally. In

quieter times my dictature would have finished, and I should have commenced my

constitutional reign. Even as it was, with a coalition always opposing me,

either secret or public, avowed or denied, there was more equality in France

than in any other country in Europe. One of my grand objects was to render education

accessible to everybody. I caused every institution to be formed upon a plan

which offered instruction to the public either gratis or at a rate so moderate

as not to be beyond the means of the peasant. The museums were thrown open to

the canaille. My canaille would have become the best educated of

the world. All my exertions were directed to illuminating the mass of the

nation instead of brutalising them by ignorance and

superstition.... There never was a king who was more the sovereign of the people

than I was. I always prided myself upon being the man of the people... Those

English who are lovers of liberty will one day lament with tears having gained

the battle of Waterloo. It was as fatal to the liberties of Europe as that of

Philippi was to those of Rome.”

Such was the general scheme of apology. The conquests

were forced upon him, but they made for the well-being of the conquered ; and

the whole foreign policy was part of the great battle for light against darkness,

which had been waged by Voltaire and continued by the men of the Revolution.

The “grand objects” were to re-establish the kingdom of Poland as a barrier

against “the barbarians of the north,” and to endow Spain with a constitution,

which would have crushed privilege and superstition and opened a full career

to talent. He admits that the Spanish War destroyed him; but the “Peninsula

could not have been left to the machinations of the English, to the intrigues,

the hopes, the pretexts of the Bourbons.” The interview of Bayonne was not an

ambush but “ an immense coup d’état.'" He had never mingled in the

intrigues of the Spanish Court, had never broken engagements with the Spanish

princes, and had used no duplicity to draw them to Bayonne. “When I saw them

at my feet and could judge by myself of their incapacity, I pitied the lot of a

great people, and seized the unique occasion which fortune presented me to

regenerate Spain, to rescue her from England, and to unite her entirely to

France.” Again, if he had been successful in crossing the Channel, he would

have founded independent republics in England and Ireland. “I would have

dethroned the House of Hanover, abolished the nobility, proclaimed liberty,

fraternity, equality... .Your canaille would have been on my side,

knowing that I am a man of the people and that I spring from the people

myself.” His designs in Italy were equally liberal. “I purposed, when I had a

second son, as I had reason to hope, to make him King of Italy, with Rome for

his capital, uniting all Italy, Naples, and Sicily into one kingdom.” The three

great obstacles to Italian unity had been the foreign dynasties, the spirit of

locality, and the residence of the Pope at Rome. In the short span of fifteen

years all had been removed, “broken by the great movement of the French

Empire.” The Pope was at Fontainebleau; and, but for the Russian campaign, the

headquarters of the Catholic religion would have been permanently transferred

to Paris. All had been prepared for the proclamation of Italian independence

upon the birth of the second son. It was settled that Prince Eugene should act

as Viceroy during the minority.

It was true that mistakes had been made in Germany.

The King of Prussia should have been deprived of his kingdom after Jena. “

After Friedland I should have taken Silesia and given it to Saxony. Had I done

this, given a free constitution, and delivered the peasants from feudal

anarchy, they would have been contented.” He thought that he should have

declared Hungary independent, that he should have subdivided Austria, that he

should at least have “devoured” Prussia before starting on his Moscow

campaign. Still, the Confederation of the Rhine and the kingdom of Westphalia,

the grand-duchy of Warsaw and the crippled state of the Hohenzollerns, were

sufficient evidence of French predominance beyond the Rhine.

The problems of the Balkan Peninsula, of Asia, Africa,

and America had not been solved; and here it was necessary to acknowledge some

failures and errors of judgment. The idea of the policy, however, was large,

magnificent, and liberal. Egypt was the key to the East; and France, once

mistress of Egypt, would have been able to unlock the treasures of India. She

would have pierced the Isthmus of Suez, and, in alliance with Russia, Persia,

and the Mahrattas, broken the British power in the East. “ Egypt once in

possession of the French, farewell India to the English.” The possession of

Egypt was also designed to secure a further advantage. The Ottoman Empire was

corrupt to the core; and though, on its inevitable dissolution, part of the

spoil would go to Russia, the remainder would fall to France, the mistress of

Egypt. During the negotiations subsequent to the Peace of Tilsit, the partition

of Turkey had been frequently discussed between Napoleon and Alexander. But,

though at first Napoleon was pleased with the Russian proposals because he

thought “ it would enlighten the world to drive those brutes the Turks out of

Europe,” mature reflexion convinced him that the plan

would endanger the equilibrium and the peace of Europe. “I considered that the

barbarians of the North were already too strong, and probably in the course of

time would overwhelm all Europe, as I now think they will.” Accordingly it

became his object to bridle the Muscovite barbarians in the interests of

European civilisation. On the one hand, he would lure

them far into the East; on the other hand he would erect strong bulwarks in the

west and south, a national kingdom of Poland, a group of German States under

French suzerainty, a French Italy, a French Egypt, possibly also a French

Constantinople. Thus he would have accomplished a work analogous to that of Leo

I and Charles Martel, of Charlemagne and Otto I, who saved the fabric of Greek

and Latin civilisation from destruction at barbarian

hands.

The great design had failed, and Europe would live to

regret it; but the failure had been the result of the incapacity of

subordinates, of incalculable accident, of the perverse policy of England, and

was in no way inherent in the design itself. An admiral’s error had lost the

battle of the Nile; the chance stroke of an assassin had destroyed the general

who could have preserved Egypt for France. And what benefits might not fifty

years of French rule have secured to Egypt! A thousand dykes would have distributed

the waters of the Nile; sugar and cotton, rice and indigo, would have been

cultivated; and the commerce of the Indies would have resumed its ancient

route. “After fifty years of possession, civilisation would have spread into the interior of Africa by the Sennaar,

Abyssinia, Darfour, and the Fezzan; several great

nations would be called to enjoy the benefits of the arts, the sciences, the

religion of the true God, for it is from Egypt that the people of central

Africa must receive light and happiness.” An elaborate argument was designed to

show that the French army could have maintained itself in the country without

help from home.

In the West Indies Napoleon had to confess to the

miscarriage of his plans. He told O’Meara that he should have declared San

Domingo free, and that he should have acknowledged the black government; for,

if this had been done, England would have lost her West Indian colonies.

However, in the notes appended to Lacroix’s memoirs, he takes a precisely

opposite line and defends the policy of the expedition, ascribing its failure

to the mistakes of Le Clerc, the intrigues of the English, and the ravages of

yellow fever. He had found it necessary to permit the slave trade and to

maintain the institution of slavery in Martinique and the De de France, but these decisions had not disturbed the course

of events in San Domingo. Slavery was founded upon antipathy of colour; and antipathy of colour could

only be overcome by polygamy. He had therefore held several consultations with

theologians with the view of preparing a measure to authorise polygamy in the French colonies, “restraining the number of wives to two, one

white, one black.” This was the solution which the legislator would be bound to

adopt, whenever it should be thought desirable to enfranchise the blacks in the

French colonies. The experiment was never made, for the naval war stripped

France of her islands; yet in the Continental System a compensation was

provided, which in time would have made Europe independent of colonial imports.

In two or three years beetroot-sugar would have been sold as cheaply in the

French market as the cane-sugar of the tropics.

Nor was this the only compensation for the temporary

hardships of war. Napoleon had made France the centre of a federal empire; and it was his intention that Paris should be the capital

of Europe, “unique, incomparable,” adorned with all the treasures of art and

science, the seat of the Papacy and of the College of Cardinals, the centre of the foreign missions, the home of the University

of France, the seminary of all the ideas and thoughts which were to sway the

course of European civilisation. In order “ to

facilitate the fusion and uniformity of the federal parts of the Empire ” he

had designed, in the Institute of Meudon, a school in

which all the princes of the Imperial House would have received a common

education. Each prince would bring with him “ten or twelve children more or less

of his own age and belonging to the first families of his country,” with

results which might easily be predicted. French principles would take root in

all the dependencies; Italy, Spain, Germany, and Holland would attach

themselves more closely to the French connexion;

foreign sovereigns would clamour for the admission of

their sons; and, looking back upon the friendships of early youth, the rulers

of Europe would be more likely to keep the peace.

Great as had been his ambition, his course was

untarnished by crime or corruption. Surveying the past from St Helena he

declares that he is astounded at his moderation. After one or two preliminary

volleys, he ordered the guns of Vendemiaire to be charged with blank cartridge.

Nothing would have been easier for him than to have procured the death of the

French and Spanish Bourbons; yet the temptation was rejected. He would probably

have pardoned the Duc d’Enghien, if Talleyrand had

not intercepted a letter in which the Duke offered his services to the new

Government of France. “My secret thought,” he said on one occasion, “ was to

give him the Constable’s sword so as to be quit of the emigres? He had

never taken a bribe; he had never bought a vote or a party by promise of place

or power; he had found great dilapidations; he had left administrative purity.

Council of State, Tribunate, Senate, all were pure and irreproachable. As for

himself he had never cared to amass wealth. “J’avais le gout de la fondation et non celui de la proprieté. Ma proprieté à moi etait dans la gloire et la celebrité."

As to the solidity of his great social experiment, the

creation of the nobility, he was under no illusions. In a singularly

penetrating way he explained one day to Las Cases that the French Revolution

had destroyed the social charms of the home, and the ease, luxury, and wealth

which form the basis of cultivated enjoyment. In consequence of this, society

took its pleasure in public entertainments. The throne had also ceased to be a

lordship, a seigneurie, and had become an office ; and the whole tone of

a modem Court differed from that of the Courts of the ancien régime. The modem Court had less social influence, for the influence of

Courts can only penetrate the nation through the medium of an aristocracy. He

had to be cautious about introducing men of the ancien régime to the Court; “for every time I touched this cord there was a

trembling of spirit, as with a horse when the reins are pulled in too tight. I

have made princes and dukes, but I could not make real nobles.” In twenty

years, however, all would have been well, for he had intended to intermarry the

new blood with the old.

He recurred to this subject at St Helena, saying that

the creation of the nobility was one of his greatest, his most complete, his

most happy ideas. He had three objects in view, all of which would in time have

been attained—to reconcile France with Europe, to amalgamate the new France

with the old, and to annihilate the feudal nobility. He claimed that his

national titles would have re-established that equality which the feudal

nobility had proscribed: “ for parchments I substituted fine actions,”

forgetting apparently that fine actions are not transmitted from father to son.

It was clear, however, that he had not succeeded in winning the Faubourg St

Germain. “ J'ai fait trop, ou trop peut” he said one day to Las Cases—enough to

discontent the democrats and not enough to attract the royalists. “If on the

return of the emigres I had attached them to myself, the aristocracy

would readily have adored me.” He goes on to speculate upon all that he would

have done to bind the ancienne noblesse to his throne. His first thought, “his true inclination,” when seeking for a

second wife, was to marry a daughter of one of the old French Houses. He would

have adopted the daughters of the Montmorencys, the Nesles, the Clissons, and married

them to foreign sovereigns. “For the good and the magic of aristocracy consist

in antiquity and in time, the sole things which I was unable to create.”

Talleyrand, his usual scapegoat, prevented advances to the emigres, and

his councillors persuaded him to the Austrian

marriage; so the Faubourg St Germain was never conciliated. We must remember

that on this occasion he was talking to a royalist.

The Imperial system might be accused of having stifled

liberty and injured education. To such allegations Napoleon replies that his

work was a torso, not a statue. The extreme centralisation of the prefectoral system was essentially

transitional, “a weapon of war”, and would in time have given way

to “our peace establishment, our local institutions”; and here he sketches out

a system of local government by unpaid magistrates somewhat after the English

plan. Again, the conscription, far from harming education, was designed to

benefit it. “Conscription is the eternal root of a nation; it purifies

morality and trains habits”; and the virtues engendered by the military life

would in time have been fortified by the instruction given in the regimental

schools which the Emperor had planned in order that the conscripts might

continue their studies. He had also devised a scheme for the improvement of

clerical education. The elements of agriculture, medicine, and law were to be

added to the theological course provided for those intending to take Orders.

Dogma and controversy would insensibly have become rarer in the pulpit; and,

while the cure would preach “pure morality” in church, he would be in a

position to give useful counsels to his parishioners on practical affairs.

He denied that the Senate was servile; he asserted

that the Tribunate was useless and expensive, and that its suppression was

sanctioned by the public voice. “J’ai toujours rnarché avec l’opinion de cinq ou six millions d'hommes." There could be no doubt as to the

solidity and excellence of his finance. “Never,” he said to Gourgaud, “has anyone brought more order and more light

into financial accounts than I. In part my good measures are due to my

knowledge of mathematics, to my clear ideas on everything.” At another time he

spoke of his Code as the “arch of salvation,” as his “ title to the

benedictions of posterity.” These were legitimate vaunts; and the noblest

monument to his memory, as he once told Montholon,

would not be a catalogue of the exploits of “ the most audacious soldier in the

history of war,” but a collection of the thoughts which he uttered in the Council

of State, and the instructions which he issued to his ministers, and a list of

the public works which were undertaken during the period of his rule.

There were moments in which bravado and apology were

cast aside, and he saw himself and the world truly. “ None but myself ever did

me any harm,” he said once to O’Meara, “I was my only enemy”; and again to Montholon, “I stretched the cord too much. I could not wait

to finish the Spanish business before I crossed the Niemen.” But of contrition

for bloodshed and treasure spent and lives broken there is no trace. He broods

over his failure and tries to explain how he should have averted it, now saying

that he should have shot Fouche after Waterloo and sent twenty deputies to the

scaffold, now that with a man like Turenne to help him he would have made

himself master of the world. In unguarded moods he shows how little he cared

for the principles of the Liberal Empire. Had he conquered at Waterloo, he

would have sent the Chambers packing. If he were back again in France, he would

close the University and entrust the education of the country to the priests. “I too have suffered from the mania for propagating the sciences, but my

experience has corrected it. We want cultivators, workmen, manufacturers, not

philosophers.”

But a reconciliation of his inconsistencies is not to

be attempted. As the mood seized him he could be brutal, cynical, obscurantist;

and who can keep the chart of his moods and thoughts? There is not a noble

sentiment which he will not pitch overboard when the scowling storm is on him;

there is hardly a proposition which stands unrefuted in the confused effulgence

of his contradictory apologies. At one moment he loudly proclaims his

beneficence, and then suddenly the notes of the edifying anthem are stopped,

and we hear the chagrined cry of the baffled schemer laying the blame of

failure on his confederates. On the whole he bore his hour of trial with a certain

noble courage, cheering his despondent and irritable companions, and himself

setting an example of resolute work. But, as hope after hope went out and

disease gained on his constitution, his giant energy flagged. At the opening of

1821 it was clear that he had not long to live; and after the end of March he

scarcely rose save to change his bed. The disease which slew him was the same

which had slain his father, cancer in the stomach; but he bore the pain with

patient fortitude and full knowledge. When Bertrand asked him what conduct his

friends should pursue and what end they should aim at, he answered with fine

magnanimity, “The interests of France and the glory of the Fatherland. I can

see no other end.” The last faint sounds caught from his lips as he expired on

May 5, 1821, are said to have been, “France, armée, tête d’armée, Josephine'"', and so in the

midst of the great hurricane he passed out of life, charging at the head of his

ghostly legions. De Tocqueville has written his epitaph— “He was as great as a

man can be without virtue.”

Men of a conservative temper who were spectators of the

downfall of the Empire were apt to see little in Napoleon’s career but a superb

and maleficent explosion of human energy, the devastations of which it would be

the duty of subsequent generations to repair. To them he was merely the last

and the greatest of the Jacobins, the upstart captain of the revolutionary and

militant democracy which had overturned the settled institutions of France and

thrown its insolent challenge at the old order of Europe. Others, taking longer

views of history, have been principally concerned with the fact that Napoleon

was a powerful dissolvent of medieval barbarism. They think of the wars of the

Empire, not merely as a great effusion of Frankish chivalry, inexhaustible, as

the Crusades themselves, in audacious and pathetic extravagance, but also as

one of the decisive episodes in the secular duel between the Latin and the

Teutonic nations. For the conquests of France involved

the acceptance of the political system which had been fashioned in the fires of

revolution; the obliteration of outworn boundaries; the destruction of the

social groupings of the feudal age, noble caste, trade guild, religious order;

the extension of a system of private law, as hostile to the Teutonic principle

of free association as it was favourable to the Roman

principle of State omnipotence. To others, again, the true significance of

Napoleon lies in the fact that he made possible the national movements of the

nineteenth century. He is the herald of Italian unity; and, alike by reason of

the things which he destroyed and by reason of the efforts which he provoked,

he takes rank as one of the makers of Germany. For the old aristocratic

federalism of the Dutch he substituted the principles which govern the modem

kingdom of Holland. It was one of his many policies to excite the national and

inextinguishable aspirations of the Poles; and quivers of hope spread even to

Serbs, Roumans, and Greeks, communicated by the mighty

movements of so many men, and the sudden catastrophe of such ancient things. If

South-American democracies value their independence, statues of the man who

destroyed the prestige of the Spanish and Portuguese monarchies might be

raised, without an excessive strain on historical propriety, in the squares of

Valparaiso or Buenos Ayres.

This, however, is not the aspect which chiefly

impressed Englishmen. That dauntless and dogged generation, who never cried

craven and never drew breath, viewed Napoleon, not with complete justification,

but also not without justification, as the tyrant who respected no pledge,

stopped short of no ambition, and flinched before no crime. They thought of him

not as the creator of nationalities (for he created none in his lifetime), but

as the destroyer of peoples and the enemy of constitutional freedom all over

the world. As the men of the fifth century regarded Attila the Hun, so, with

few exceptions, did the contemporaries of Pitt and Liverpool regard Napoleon.

The thunders of the storm have now long died away; and we see that some

precious seeds were borne upon the hurricane. Nor did they fall upon the

continent of Europe alone. The maritime and colonial power of England was

fortified by a war which gave us Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope, promoted the

occupation of Australia, and led to the destruction of the Mahratta power in

India. The sea-power of France, broken by the disorders of the Revolution, was

finally shattered by the wars of the Empire. So impressive was the aggrandisement of England beyond the seas that some writers

have regarded the augmentation of the British Empire as the most important

result of Napoleon’s career.

What was his legacy to France? To the extravagance of

his later projects France owes the loss of the Rhine frontier, which had been

the earliest conquest of the revolutionary arms, and the immemorial ambition of

French diplomacy. That he terminated the romance of the Revolution, that he

founded a government above party, that he healed the schism in the Church, and

conciliated the principles of social equality and political order—all this is

acknowledged even by his enemies. To his resolute energy France owes the rapid

completion and the wide reputation of her Codes; nor has any great modern

community of men received so much from a single human mind. His economic

legislation is open to criticism, even granting his own assumptions. Was it

wise for a government resting upon the support of the peasantry to promote the

growth of towns by giving high protection to manufactures? Was it statesmanlike

to exclude the manufactures of Italy and Germany from the French market? Was

it not chimerical to suppose that Europe could be made independent of tropical

produce? Socialism had been the peril which, in the eyes of the middle

classes, had justified the Consulate; and socialists can find little comfort in

the Civil Code. Napoleon believed in the magic of private property; and it was

left for the Second Empire to legalise trade-unions.

His religious policy had issues widely different from those which he intended;

for a Church, pinched, policed, and bullied by the State, was inevitably thrown

back upon the support of the Papacy. If the Revolution, by confiscating the

Church lands, destroyed the Gallicanism beloved by St Louis and Bossuet,

Napoleon promoted that modern form of Ultramontanism which wages a truceless

war against the very foundations of the democratic State. The Revolution broke

with religion and sowed the seeds of martyrdom. Napoleon exploited it, and

promoted at once clerical opportunism and Ultramontane zeal. The idea of a vast

community, organised on a rigid plan and trained to a

definite end, will always continue to fascinate minds impatient of the free and

miscellaneous movements of human activity. In attempting to control all the

sources of spiritual and intellectual influence in France, Napoleon essayed a

task beyond the compass of any man or any government. The frontiers of liberty

and authority must necessarily shift from age to age and from occasion to

occasion. When Napoleon grasped the helm of State, France needed a spell of

strong government. This he gave her, and more besides. He gave her a scheme of

education framed to meet the needs of a military despotism. He restored the

administrative centralisation of the ancien régime, with those improvements which

the Revolution had rendered possible—a centralisation scientific, uniform, all-pervasive, untrammelled by

the spirit of locality, caste, or corporation; and men trained in the

Napoleonic school have worked the machine of French government ever since.