|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

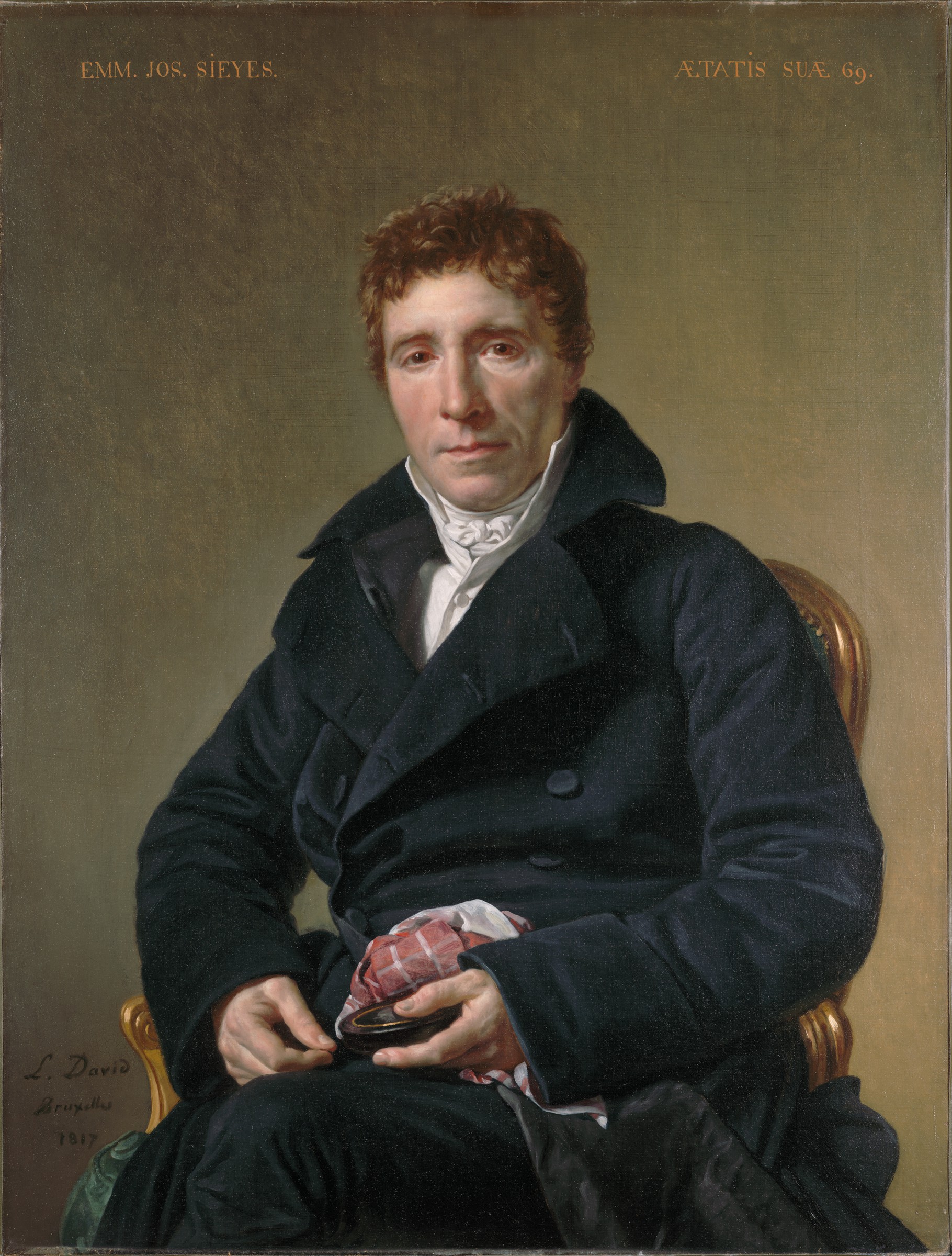

THE ABBÉ SIEYÈS

AN ESSAY IN THE POLITICS OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

BY

I. SIEYÈS BEFORE THE REVOLUTION, AND THE MAKING

OF HIS OPINIONS

II. THE ATTACK ON THE ANCIEN RÉGIME

III. THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY AND THE FIRST

SCHEME OF CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM

IV. SIEYÈS AND THE FALL OF THE MONARCHY

V. THE CONVENTION AND ITS COMMITTEES

VI. THE FOREIGN POLICY OF SIEYES AND THE MISSION

TO BERLIN

VII. THE FALL OF THE DIRECTORY

VIII. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1799 AND THE OLD AGE OF

SIEYÈS

CHAPTER I.

SIEYÈS BEFORE THE EVOLUTIONM AND THE MAKING OF HIS OPINIONS.

On June 22nd, 1836, the Moniteur announced that “M. Syeyes, sometime member of the

Constituent Assembly and of the Convention, Director and Consul of the

Republic, count and peer of the Empire, member of the Institute,” had died two

days earlier at his house, No. 119, Faubourg Saint Honoré. These were the

titles that had come to the man whom history knows as the Abbé Sieyès during

more than six-and-twenty years of revolution and change, from the day he was

chosen to represent Paris in the States General at Versailles to the day he

entered Brussels, a fugitive regicide and Bonapartist. During the first ten

years of his public life he was seldom out of office, seldom absent from Paris,

never altogether without influence. Under the Consulate and Empire he remained

on the stage, robed and titled and silent, discontented with his part,

distrusted by the leading actor, and ageing fast. Sixty-seven when he went into

exile, he spent the last twenty years of his life in obscurity and became a

legendary figure before he died.

No one ever argued that Sieyès was a great statesman.

He made his mark as the author of what is probably the most famous pamphlet

ever printed? Soon he claimed the title and acquired the reputation of a

profound doctor in politics. Adversaries ridiculed his claims and liked to

treat him as the mere academic politician, who has strayed into active life and

there made shipwreck. They learnt in time that, whatever the value of his

principles, he had long and sure sight. He had a genius, it has been rightly said,

for finding the key to a given political position. Hence a dangerous tactician,

whose influence both on ideas and on affairs had to be reckoned with at each

crisis of the Revolution. The court, while a court survived, counted him among it most formidable enemies. In 1794, a rumour ran from capital to capital in Europe that he was the unseen agent who moved

Robespierre and made the Terror. Robespierre meanwhile was denouncing him as “the mole of the Revolution,” the creature whose secret working undermined the

ground on every side. Five years later, when he was reluctantly setting

Bonaparte in power, one of his wisest enemies reminded those who made light of

his ability that he was far more than a mere “political metaphysician”—a man

“fertile in practical expedients, who knew how to keep silence and bide his

time,” than whom “no one knew better how to control himself and secure control

over others when some great end demanded it.” This judgment is true, and the

stories of his activity during the Terror, though false, spring from’ a just

reading of his character. Throughout the ten great years of his life he worked

steadily for definite ends, sometimes in the open, sometimes under cover, and

his work was not wasted.

The political ideals that Sieyès set before him, his “metaphysics,” give the chief interest to his strange career. His acts are

interesting enough and have received less consecutive study than have those of

many of his political inferiors; yet taken alone they are but moderately

fruitful. The long-sighted tactician was certainly a statesman of the second,

many would hold of a far lower, rank. The man as we know him is

unattractive—hard, bitter, unloving, egotistical and self-righteous, though

mellowed somewhat in old age. But for the thinker is claimed an important place

in the history of political science, rather than that reputation of a facile

artisan of unworkable Constitutions which is his ordinary portion. Should the

claim be rejected, he would remain significant. Not least because he was in

fact what many of his contemporaries have been wrongly called: a man who

entered on the career of a revolutionary leader provided with a scheme of

political reconstruction, drawn rather from “general principles” than from

history; who, as occasion offered, brought forward proposal after proposal,

almost every one of which can be fitted into its place in that coherent scheme.

His proposals often became the sport of the great blind forces that worked

beneath the surface of the Revolution, and as the years passed he learnt both

good and evil from experience. But he never became a mere opportunist, and in

his later years deserved Napoleon’s honourably contemptuous

nickname of “ideologue.” Had his doctrine been given to the world in books, in

books decently readable, and applied by others, he would not have lacked the

editors and commentators who crowd about many a third-rate thinker. It was

actually given in pamphlets, printed speeches, and drafts of legislation—not

infrequently crabbed—and applied by himself, sometimes with indifferent

success. Such conditions would have endangered the reputation of far greater

political speculators. And as he has not stood high in the favour of any school of historians, for a variety of reasons, some of which are good,

what he wrote has never been collected since German disciples published during

their master’s lifetime a translation of the chief pamphlets and drafts, which

is now exceedingly rare.

The Sieyès family belonged to the upper bourgeoisie of

the town of Frejus, in the old Provence and the

modern department of Var. Honord, the father, held

some minor offices under government—postmaster of his native town and collector

of the king’s feudal dues. He owned a little land and had married a wife connected

with the lower ranks of the nobility, the gentlemen of mean estate who swarmed

in ancient France. Emmanuel Joseph, the fifth child, was born on May 3rd, 1748.

His parents gave him the best education that they could secure, first at home

under a tutor, then in the Jesuits’ College at Frèjus, afterwards in a school

directed by the Fathers of the Christian Doctrine at Draguignan. It seems that

many boys from the Draguignan school passed into the royal academies for the

artillery and the engineers, and that Emmanuel wished to do the same. So at

least his memory told him in later years; but as his parents decided his career

when he was only thirteen, his military tastes cannot have been matured. Honore

and Anne Sieyes were devout people, but they thought it no sin to make a priest

of their clever son against his will. The Bishop of Frèjus was a friend of the

family, and the bishop had talked of the swift preferment that awaited clever

lads in the Church. So the boy was packed off to Paris, with tears and protests,

to go through the philosophical and theological courses in the Seminary of St.

Sulpice.

Emmanuel, it would seem, was a child with no religious

bent, who never acquired so much as an interest in the service of the Church.

The long years of his ecclesiastical apprenticeship were a weariness to him.

Neither the ancient and elaborate theology of Rome nor the kindly deism of the

vicar from Savoy made any appeal, so far as one can tell. In the end, he was

asked to remove himself from St. Sulpice, his superiors having found out that

his private reading had given him “a taste for the new philosophical

principles.” He must have been about twenty when a more indulgent seminary,

that of St. Firmin, took him in and gave him leisure to complete his studies

for the degree of licentiate in theology at the Sorbonne. At the end of his

academic life the authorities wrote with easy tolerance that his bishop “ might

make of him a gentlemanlike and cultured canon, but that he was by no means

fitted for the ministry of the Church.” A man of nicer conscience would have

abandoned the ecclesiastical career, as did Turgot; but preferment was to be

had by orthodox and unorthodox alike, and Sieyes was anxious to make his way in

a world full of unbelieving literary abbés. His theological

interest did not carry him so far as the doctor’s degree, but he was ordained

priest in 1773 and went out to seek his fortune in the last ignoble year of

Louis “the well Beloved.”

St. Sulpice had judged wisely. Before he was ordained,

as he boasted twenty years afterwards, Sieyes had t( succeeded in dismissing

from his own mind every notion or sentiment of a superstitious nature”—a

complete preparation for the Christian ministry. He “was struck, upon entering

into the world, to find it in a state of greater advancement” in these things “than he had supposed”; for the disintegrating effect

of a century’s criticism on old faiths and old institutions had done its work

more effectively than they knew in the seminaries. The cultivated people whose

society he sought had agreed to treat Christianity, more particularly Roman

Christianity, as a spent force not even worth careful study. It was all

“superstition.” Yet most of them held that society needed religion. Their

masters, the philosophers, were not, as has been recently and rightly said,

“lay spirits” in the very precise and uncompromising sense in which that term

is employed in contemporary France. Sieyès himself must have been among the

most “lay” of his circle, both in opinion and sentiment, as is not uncommon

among people brought into close compulsory contact with religious organisation, who believe that they have found nothing

behind. But even Sieyès, whose scheme of things found no place for the Church

and no place for God, began early to dream of a national earth-religion, a

worship of nature and humanity, that was to have its splendid ceremonial

and—although he would not have admitted this—its own dogmatics. He was a

learned musician and no mean performer. They say that he used even to sing the

gay little ballads and sentimental airs that were in vogue in the days of hoops

and sensibility. And he loved to picture to himself the part that music was to

play in the solemnities of the ideal rational society of his dreams.

It was the study of “works of metaphysics and morality” that first alarmed his superiors at St. Sulpice. His favourite philosophers, he once said, were Locke, Condillac and Bonnet, and the book that he had most often read was Condillac’s Essai sur Vorigine des connaissances humaines. The Abbé de Condillac, perhaps the most universal and most representative though not the most seminal thinker of the century, was still writing when Sieyès was ordained. One of the books by which he is best known today—Le Commerce et le Gouvernement, a book that admirers have ranked with the Wealth of Nations—appeared at Amsterdam in 1776. In 1780 its author died, after visiting most fields of thought. His theory of knowledge, like his theory of politics, is in the direct line from Locke. He shares with Bonnet the honour, such as it is, of having hit on the illustration of the statue, that is endowed with the senses in succession, to elucidate the hypothesis that the mind contains nothing which it has not received from the material world, through the known channels of sense. His psychology runs clear and thin: he hates mystery and all vagueness in thought or word: he longs to give to every science the exactitude of mathematics and to make language as simple and universal as algebra: he holds that “ the true philosophy is barely born,” for “by philosophy he understands the knowledge of nature” that began with Copernicus and was carried forward towards victory by Newton. In short, an intellectual

ancestor of nineteenth-century naturalism who, however, accommodated his

naturalism—somewhat awkwardly—to an anti-papal Christianity that may well have

been as sincere as that of Locke or Newton. Bonnet is of the same intellectual

stock. He came to psychology from natural history. He was the first careful

student of the psychology of the severed worm, and he had hazarded the

conjecture that “the plants and animals which exist today have proceeded by a

sort of natural evolution from the living beings that peopled the first world,

as it came from the hands of the Creator.” A devout spirit, into the stuff of

whose natural philosophy religion, the fatalistic religion of Geneva that

accords well with the rule of law, is woven in a very striking way. His

influence on Sieyes must have been exclusively philosophic, for unlike Locke

and Condillac he never concerned himself with the

doctrine of society and government.

Leaving on one side what was “superstitious” in the

philosophic teaching of his masters, Sieyès fastened on what was positive. He,

too, knew something of mathematics and had read his Principles. He endorsed

gladly Condillac’s contempt for all philosophy that

was not of his own age, and drew from Condillac’s theory of knowledge definitely agnostic conclusions that its author had never

drawn. And he fortified the conclusions with an argument that in certain phases

of religious history is overwhelmingly strong: religion, in explaining natural

phenomena by the direct action of the Divine Will, had hindered philosophers in

their search for physical and alterable causes of human ills, and so retarded

mankind in its pursuit of social happiness: therefore religion “was the first

enemy of man.” All Christian faith was gone; but the psychology of Condillac’s school helped Sieyes to enthrone in its place

what has been called the “common and mystic faith” of the men of 1789, the

faith in progress. At birth the mind of man was a blank page. All the writing

on it came during life and through the senses. If there was no window of the

soul through which shone a “Light that lighteth every

man coming into the world,” neither was there any inborn bias towards lower

things. The only current doctrine of heredity was the doctrine of original sin,

and that was out of court. Man was a rational animal, rational throughout, but

certain anti-rational powers—old enemies of his, like religion, and stupid

reverence of kings, enemies whose existence the philosophers deplored yet did

not explain—had come between him and truth. Education once made universal and

reasonable, the educated man once set in a rationally organised society, and all would be well: the world’s moral and social progress would

become increasingly and indefinitely rapid. This was the faith, not proven but

not all false, that made men like Sieyes and Condorcet seek to become

legislators of Solon’s kind—framers of whole commonwealths. Just beyond the

struggles of the first great legislation lay the new age.

Contemporaries and historians have often asked what

traces the years of ecclesiastical training and service left on Sieyes’ mental

equipment and character. To this there is no easy and certain answer. Enemies

of the man or of the Church of course traced to them all his failings, his supposed

excessive subtlety, or the dogmatic bent of his mind. There may be some such

connection, but if he worked principles as old theologians worked texts, and

sometimes he did, that was a trick that may have been acquired from more than

one philosophic or economic contemporary. And dogmatism may be learnt in any

street. With more insight it has been suggested that his skill in analysing political situations and his “intense realisation of the harmony necessary in social and

political organisations” were stimulated by his

training as an official of the oldest, most complex, yet most stable of bodies

corporate. That body he hated, as he hated most of the other corporate bodies

of the old order, Parlements and chartered companies

and gilds. Like all his generation, whatever their political creed, he was

disposed to leave immense power in the hands of the State. He wished the law to

check, and hoped that social progress would in time supersede, these

distasteful corporations. Before his career was over he was to become a

religious persecutor. And yet, at the very height of the Revolution, he would

not share that almost universal prejudice of contemporary reformers against

social organisms other than the State, which led them to prohibit associations of

working men, attempt to establish a government monopoly in education for fear

of competing powers, and decree in so many words (August 18th, 1792) that “an

absolutely free State cannot allow any corporations within its bosom.’’ The

modern school of French anti-clerical historians that speaks, from the thick of

the fight with the Church, of “ the eminent and exclusive right of the State to

direct public instruction,” naturally tends to blame Sieyes for this. Others

may appreciate that liberal belief in the value to society of freely-formed

associations which he professed, though he did not always act up to his

profession, and may connect it with his early experience of the great

Association whose aim he disliked but whose principle, whose right to existence,

he long continued to respect.

The political superstructure to his philosophic faith

was built up by Sieyès, gradually but very firmly, in the years of his maturity

from 1774 to 1787. That striking contrast between his vocation and his

opinions, he says, was “perhaps the motive which most strongly induced him to

examine the mixture of classes, professions, and occupations, of which

political society is composed, and to discover, in the great machine of social

life, what parts are useful and what redundant or burdensome.” During those

years he learnt men as well as books, won for himself a place in the

administrative work of the Church and a right of speech in the salons of Paris.

At first the struggle for life and fortune was hard. The cost of a

long-drawn-out education had been heavy and the father wearied of the burden.

He had a friend at court, a young abbé to whom he had lent money, from whom

much was expected. But the first efforts of this Abbé de Césarge to procure

some post for Emmanuel came to nothing. Honore was annoyed. He cut down his

son’s allowance, even threatened to stop it altogether, alleging that his means

could stand no further drain. Emmanuel complained bitterly, ran into debt, and

induced clerical friends to back his appeals for funds. When the funds had been

secured he plunged again into his studies—economics this time—and waited on

events.

With the accession of Louis XVI, in 1774, the efforts

of the influential friends, Césarge, the Bishop of Frèjus and others, began to

tell. Sieyès was promised the reversion of a canon’s stall, and in August,

1775, he became secretary to Lubersac, the newly

appointed Bishop of Treguier, in Brittany. Paris he

left with regret, but he won two quiet years among his books ; for the light

duties of his post left him leisure enough, and he was careful neither to

preach nor hear confession. Yet he wearied for the life of town, and sickened

in the drowsy ecclesiastical air of his little cathedral city. At last he

secured permission to suspend his duties, but draw his stipend from Paris.

Satisfactory as this was, there was always the risk that Lubersac might want a working secretary. Sieyes accordingly cast about him for a post in

Paris or Versailles. He set his heart on a chaplaincy in the house of the

King’s aunt, Mme. Sophie, and seems to have expected Lubersac to help get it for him. When the bishop showed slackness, even unwillingness,

in the chase, the young philosopher broke out into a howl of irritation in his

home letters. Lubersac, he wrote, was playing him

false: he was sick of the selfishness and meanness of these courtiers: probably

“the old devil”—who was perfectly incompetent—wanted to thrust on him the

full dreary routine of administration at Treguier and

leave him there all the year round. Debts, disappointments and ill-health—he

was never robust—were not improving a temper naturally morose.

Towards 1780 better fortune, and with it more

contentment, set in. The struggle for a footing was over, and Sieyès could

turn at will to his studies or to the eager political and literary life of the

decade that preceded the Revolution. In 1779 he came into possession of his

canonry, and when Lubersac was translated from Treguier to Chartres he rewarded his late secretary with

the appointment of vicar-general in the new diocese. Mme. Sophie’s chaplaincy

was also secured, though lost again at the death of the great lady in 1782.

After that, royal patronage ceased; for, as it would seem, the abbe’s growing

familiarity with reformers of all classes and his known contempt for the

existing order made him unfit for office about the court. But the posts that he

held already provided an adequate living, and probably a little money came to

him from his father, who died in 1782, so that there was no longer need to

sacrifice his hardening convictions to his prospects.

There had always been a sort of affection between Honoré, Sieyès and Emmanuel in spite of many differences. Emmanuel, while still uncertain as to his own future, could not be induced to take much interest in the financial and matrimonial prospects of the family. One brother decided late in life to follow him into the Church, and it was naturally expected that the clever son would assist his education or seek out an appointment. Emmanuel was coolly indifferent. He had never forgiven his parents for driving him into a career that he detested, yet had not found courage to abandon, and he declined to recognise claims based on the sacrifices that they had made for his education, least of all when the matter in question was the making of another priest. So there was distress at Frèjus and a pitiful angry letter went to Paris. That was in 1779, when the turn in Emmanuel’s fortunes was hardly complete. It is perhaps fair to add that his brothers at this time can have been little but names to him : the question was one of family loyalty rather than of love. Love shows but seldom in the correspondence that has come into print, save now and then in tender inquiries as to the health and welfare of the mother. After the father’s death very little is known of any relations with his own kin. One brother, J. B. Sieyès, Seigneur de la Baume, became a lawyer, and subsequently an obscure private member of the National Assembly. We hear of stopped, saying: “Je ne dirai pas la messe pour la canaille. The story is of the

same class as one accepted uncritically by Taine, that Sieyes joined the

revolutionary side because he was refused an abbey that he coveted. Neither has

any respectable authority. him frequenting the society of Emmanuel’s admirers

in 1789. In 1791 he returned to Frèjus. In 1800 he became a member of the High

Court and settled in Paris. Another brother—probably Leonce—was consul at

Naples in 1798. After 1800 a nephew and nieces come to light, children of this

second brother, but the shadowy existence of these people in the background

only throws up the lonely figure of Sieyès, priest and ex-priest, during his

working-day. They draw nearer as the evening closes; but his real life as we

know it is all lived alone and all as it were official. There is the record of

his ideas, of his public acts, of his political intercourse, now and again a

half intimate story; little else of any sort. Had there been much else,

history’s judgment of him might perhaps have been a trifle more friendly;

though the early correspondence that has come to light has added only a very

little human kindness to the gaunt self-centred figure of the working day.

Between 1783 and 1787 Sieyès is almost lost to sight.

We know that he had acquired a considerable professional reputation as a man of

business. At Chartres he was chancellor of the chapter as well as

vicar-general, and he represented his diocese in clerical gatherings at Paris,

as he had formerly represented Treguier in the

Estates of Brittany, thus acquiring such knowledge of deliberative assemblies

as old France could give. We know also that he was extending his acquaintance

among reformers, and had become a well-known figure in philosophical circles.

And it is believed that he became a Freemason, and joined that famous Lodge of

the Nine Sisters which counted among its members La Rochefoucauld and Bailly,

Collot d’Herbois and Rabaud Saint Etienne, Camille Desmoulins, Potion and Danton. His intellectual

occupation was the completion of his political doctrine, of his system, as they

said in the eighteenth century. Now of systems the master Condillac had written:—“A system is nothing but the arrangement of the different parts

of an art or a science in an order such that they will support one another

mutually, and such that the earlier will explain the later. Those parts that

account for the rest are called principles, and the system is the more perfect

the fewer are those principles: it is desirable even to reduce them to a single

one.” And again: “There is no science and no art in which systems cannot be

made ; but in some the aim is to account for results, in others to prepare them

and bring them to the birth. The former is the object of physics, the latter of

politics.” And again: “If there is a sphere in which people are prejudiced

against systems, that sphere is politics. ... Yet is it possible to rule a

state if one does not embrace all its parts in a, general view, does not bind

them to one another, so as to make them move in harmony, and from some single

and common spring?” These sayings it will be well to bear in mind.

There was a general agreement among enlightened men in

the reign of Louis XVI as to the immediate need for certain long-debated legal

and administrative reforms in France. Law was to be uniform throughout the

country. The advocate of Voltaire’s dialogue, who defended the forty-four

different customary laws with the argument that you had at least as many

customary pints, was silenced. Pints also were to become uniform, as they were

supposed to be among the English, who had “one measure, but twenty different

religions to make up for it.” Unified law was to be the same for all classes;

the privileges of clergy and nobility must cease. Trade, at least internal

trade, was to be free; fish was no more to pay eight-and-twenty tolls between

the Channel and Paris, the gilds no longer to block the entry and exercise of

trades. Torture and the inquisitorial criminal procedure were to be abolished.

Thought, speech, and the press were to be freed. Marriage was to become a civil

contract; divorce and usury to be legalised. The

taxes were to be reorganised so as to bear equitably

on all classes. Education was to be made a national concern, as in the ancient

republics. Local self-government was to be encouraged: its encouragement had in

fact begun. And in connection with this there was a growing, if not yet a

general, demand for a redivision of France to facilitate both local and

central administration, as a result of which the bewildering existing divisions—different for each function of government and precise for none—would disappear.

Such were the chief matters that were already almost beyond debate.

On the constitutional question there was no unanimity

even among reformers. The unanimity with regard to legal reform was itself a

new thing. A generation earlier Montesquieu had treated local customs,

peculiarities, and privileges as a not undesirable part of the mechanism of

great states. Subsequently Rousseau, who disliked such states, had based his dislike

partly on the necessity, which he conceived lay upon them, of tolerating

diversities of law to suit the differing needs of their various provinces. The

reformers of the seventies and eighties were themselves faced with the

difficult problem—how at the same time to stimulate local government and stifle

local privilege? how to combine uniformity and empire? Here, where the legal

and constitutional problems blended, the most accredited teachings were

conflicting or inadequate. Those of Montesquieu and Rousseau obviously offered

little to great states seeking radical reform. Their authors, bred in the

classical tradition, were biassed in favour of the smaller states of the ancient world.

Montesquieu, who did not believe that forms of government could be

transplanted, reserved his warmest phrases for republican Rome, the state which

drew its strength from that political virtue which consists in the love of

country and the love of equality, and is nourished by a general uniform

education. But France was too great for such equality and uniformity. She was

tied to her past. To her monarchy, as it had been before Louis XIV and the

Cardinals, she might return ; it would be madness to attempt any greater

change. And this old monarchy carried with it an hereditary aristocracy,

privilege, and inequality before the law.

Rousseau had stated explicitly that thoroughgoing

political reconstruction, legislation after the pattern of Lycurgus or Numa,

could be undertaken with advantage only amongst a people which “whilst united

by community of origin had not yet borne the true yoke of law; which had no

deep-rooted customs or superstitions; which was not in danger of sudden

invasion; in which every member could be known by all; which could do without

other peoples and which other peoples could do without; which was neither rich

nor poor, yet self-sufficient.” He reckoned Corsica the one country in Europe

still “capable of legislation.” In another place he had hinted that “the

external power of a great people could be united with the simple administration

and good order of a small state ” by means of the federal system; so perhaps

he believed “legislation” still possible in federal republics. But there is no

reason to suppose that he thought it possible for France.

It is a commonplace of history that the desire for a

strong, swift and efficient central power in great empires, coupled in some

cases with contempt for the mob, had turned many reforming thinkers of the

mid-eighteenth century into the friends and flatterers of enlightened

despotism. Some desired a restless and efficient despot, like Frederick, Joseph

or Catherine; others preferred a Sovereign strong enough to stop the

unwholesome activities of class and corporation, but endowed with a

self-restraint that would enable him, for the most part, to refrain from

law-making and commit society to the beneficent working of “natural law.”

This was the inclination of Quesnay and his direct disciples, who spent

themselves in rapturous accounts of that Chinese despotism which, as they

supposed, conformed to the ideal type. Others, again, although more democratic

in sympathy, still assigned a high place to the power which alone in most

continental states seemed capable of initiating reform. Of these the most

important, especially in his relation to Sieyes, is Condillac’s elder brother, Gabriel Bonnot de Mably.

Mably, who was as prolific as Condillac,

began to publish in 1740, but his most important political and social work only

appeared between 1763 and 1784, some of it having been held back by the higher

powers because of its dangerous tendencies. A devout admirer of the ancients,

his ideal nearly resembled Plato’s republic, for he was interested in politics

mainly on the moral side. He loved the communistic life of simple agricultural

peoples, and would have cured the evils of society by strict sumptuary laws,

the equal distribution of landed property, and the supervision of its use by

the state. Inequality, however slight, would lead to some measure of class

tyranny.

Therefore, where equality was not immediately

attainable—as in most modern States—a monarch placed high above the classes

was necessary. Mably had persuaded himself that in the beginning the French

monarchy was democratic. His Observations on the History of France, published

in 1765, expounded and popularised this opinion. Like

Montesquieu he would have. France take counsel with the ghost of her own past,

but his reading of the past was not Montesquieu’s. He saw there a really

representative States General, and his hope was that a king would some day dare to summon such a democratic parliament. That

the Crown or an hereditary upper chamber should exercise any veto on

legislation he regarded as a manifest injustice; and he was severe in his

criticism of contemporary England—the royal power was far too great, its abuse

far too easy. In France he hardly dared to hope for reform, and must perforce

wait for it from above. Called upon to write a treatise on the study of history

for the little Prince Ferdinand of Parma, his brother’s pupil, he besought him

at the close to abolish privilege, make equal laws, limit luxury, check

excessive wealth and stop all desperate poverty by sumptuary laws, separate

executive from legislative power, and transfer the latter intact to an assembly

of Estates elected freely and without corruption. So he would go down to

posterity as the father of Parma and Piacenza. One can imagine the counsel that

Mably might have given, had he lived to become one of the pamphleteers of 1789.

Partly as the result of Mably’s influence, the desire

for a revival of representative institutions was widespread before Sieyes left

the Seminary of St. Firmin. The vogue of the English Constitution was of old

standing. To many it had seemed that the English system, or some approximation

to it, actually would prove—as Montesquieu had implied—the surest guarantee of

such liberty and equality as was possible to the moderns. Montesquieu’s

pessimistic doubts as to the value of an import trade in institutions they had

set aside. The English model found room for monarchy, aristocracy, an

independent body of judges, ostensibly popular control of legislation and

finance, and a uniform system of law. Among political speculators its vogue was

already over : Rousseau despised it, Mably suspected it; but men of affairs

still sometimes hoped to revive the States General in some modified form, to

retain the old legal corporations, the Parlements,

with their traditions of opposition to royal authority, and so to establish in

France that separation of powers—executive, legislative and judicial—which

Montesquieu, developing the thought of Locke, had declared essential to the

stability of “ mixed ” governments like the English.

But the English model was not adjustable to French

society. The difference between peerage and noblesse alone meant a revolution

before it could be copied. And Frenchmen came to think that if there was to be

a revolution, the result should be something more artistic and more effective

than the system that found room for Lord North, Dunning’s motion, and the

refusal of Catholic emancipation. Moreover, the remnants of representative

institutions that France retained, and the first new representative institutions with which she made experiment, were of a class that England did

not possess and did not try to create for another century. The assemblies of

Estates which still lingered in some French provinces, the memories of Estates

that were cherished in others, were not very effective political forces; yet

they embodied, however imperfectly, the principle of local representative

government. That principle, in a dilute form, was favoured by Turgot, and by him was blended so completely with the principle of national

representative government, that from the time of his ministry (1774—6) onwards

French reformers could not think of the two things separately, and would not

tolerate a system that provided for the latter imperfectly and for the former

not at all. Not that Turgot ever proposed to give legislative power to

representative assemblies. He had sympathies with the multitude. Not had he

ever put forward a strictly democratic scheme. What he asked the King to do,

in the great report written for him by Dupont de Nemours, was to create in

parishes, “districts,” provinces and the nation a series of elective

assemblies, the parish assembly chosen by all persons holding land of a certain

value, the district assembly composed of nominees of the parish assembly, and

so on upwards. They were to give advice to the Crown and assent to the local

distribution of the burdens of taxation; they were to superintend certain

branches of local administration, but neither to legislate nor in any wide

sense to administrate. At the bottom, the parish meetings were to be electing

bodies and no more.

Turgot intended that this system should supersede the

remnants of the Provincial Estates and obviate any pretext or necessity for

summoning States General. Efficient administrator, sound monarchist, despiser

of class privileges and local pretensions as he was, he wished to get rid of

the confusion, the intrigues, the esprit de corps, the animosities and

prejudices of order against order” that marked the system of Estates, in which

nobles, clergy, and Tiers État discussed and voted separately. Had his plan

been carried through, the States General of 1789 need never have met. But his

plan involved revolution, and must have led to further revolution; for everyone

with democratic sympathies—Condorcet, for example, in his essay on the

Provincial Assemblies—saw how the system might be utilised to nourish local and national self-government. Nothing came of the plan during

Turgot’s ministry; but it was taken up later, and—more important still—about it crystallised a democratic doctrine of legislation and

an ultrademocratic doctrine of administration, which savoured little of eighteenth century England.

From all the praise of republican virtues, all the protestations

of love for Sparta, Rome and Switzerland, that are so wearisomely frequent

along the whole line from Montesquieu to Mably, there had issued little, if

any, decided dislike of .the French Crown. Even the part played by France and

Frenchmen in the American Revolution did not bear immediate fruit in republican

conviction.1 America taught how rights might be deduced and proclaimed,

principles defended, governments created, the past defied, the future bound by

constitutional devices. No doubt it prepared the way for republicanism, but as

yet the way was unused. In France the King had always been the symbol of

national unity and greatness; to his person the mass of the nation was

fervently if ignorantly devoted. Men of education knew that in old days, when

the King had been weak or a child, provincial patriotism and aristrocratic ambition had threatened the life of the

State. But the conception of a King who is the first servant of the law, a

conception derived in part from Locke and the English Revolution, in part from

the best memories of the French monarchy itself, was common to almost all who

had the power to conceive. Whether law was pictured, after the manner of

Quesnay and the economists, as that natural order to which a wise monarch will

submit; or, according to Rousseau, as the expressed will of the sovereign

people; or, somewhat after the English fashion, as the joint product of King

and his representative subjects, the result was the same. Even the friends of

the enlightened . despots felt that enlightenment must exclude the very shadow

of arbitrary rule.

Of all the more or less finished systems that lay to

his hand, Sieyes probably liked best the “republican monarchy” of Mably; but he

was in no sense Mably’s disciple. Mably based his doctrine on a reading of the

past, or at least strengthened it by an appeal to the past. Sieyes thought the

past was illegible and, apart from its illegibility, worthless. He knew that a

statesman must take some account of national antecedents, as of the political

circumstances of the moment, when deciding on the expediency of particular

proposals ; but he denied the right of the past to mould ideals. “Men enough have busied themselves in combining servile notions, which

always coincide with the facts,” he wrote before the Revolution. “When one

broods over these notions... one is constrained to tell oneself at every page

that sound politics is not the science of what is, but of what should be.” And

he added, with a reminiscence of Condillac, “ Suppose

we call the plan of a building which does not yet exist a romance; well, a

romance is assuredly a mad thing in physics, but it may be an excellent thing

in politics. I do not see why an attempt should be made to prescribe one

uniform procedure for all the sciences... Let the physicist content himself

with observation, with the accumulation of facts—nothing could be wiser...

Physics can only be the knowledge of what is. But art, whose aim is to bend and

fit the facts to our needs and to our tastes, art is our possession. We can

both speculate and realise our speculations. It is

well not to observe only, but to foresee effects and rule them, by uniting or

separating, by strengthening or weakening the causes. You must allow that here

the most useful artisan is not the one who knows and will see nothing beyond

what is. Looking with shrewd scepticism, and

the arrogance of a man nourished on a new philosophy, at the conflicting

interpretations of the past offered by his contemporaries, he concluded that

“to judge of what happens by what has happened is to judge the known by the

unknown. It is safer to judge the past by the present and to agree that the

so-called historical truths have no more reality than the so-called religious

truths.”

Arguments drawn from observation and “the nature of

man” were to replace those drawn from what claimed to be the experience of

men. There was the standing, and now familiar, danger besetting this method

that “ man ” was apt to be a creature without temporal or local idiosyncrasies,

cousin to the animated statue of Condillac. Sieyès knew,

none better, that the Frenchmen of his day were compact of passion and

prejudice; but he believed that “man,” properly arranged in society, educated,

and started on the right way, would conform to all the rules of universal

reason. And he was sure that he knew what “man” was like at bottom. After five

years’ experience in the Revolution, he could still write how in the lonely

years at St. Sulpice he had acquired “that knowledge of man, so often and so

mistakenly confused with the knowledge of men, that is, with the little

experience of the intrigues ... of a little group of people.”

Contempt for history had compensating advantages. In

Sieyès’ day more intellectual independence was needed to reject the authority

of the classics than to reject that of the Church. This independence he

possessed. He was never misled by classical analogies. He attached no vague mystical

meaning to the word republican. He knew a republic for what it is, a form of

government among other forms. Such classical knowledge as he had he used, and

some of his schemes show the marks of the ancient world. But he was never

mastered by that knowledge, never thought that an appeal to ancient authority

could serve instead of an argument. Nor are his writings and speeches stuffed

with the conventional classical references of his day, an omission grateful to

the student of revolutionary rhetoric.

And if the Greeks received no superstitious worship,

still less did that other idol of the market-place, “man in the state of

nature.” Sieyès had learnt to employ the well-worn conception of the state of

nature to explain the existence of political society; but he neither believed

in a golden age nor liked primitive communities. Existing society he found

complex. His aim was to make its mechanism more efficient, more uniform in

general plan and motive power, not necessarily simpler in its working parts.

Accepting the doctrine of popular sovereignty, very nearly in the form given to

it by Rousseau, he refused to identify it with what he counted the barbarous

expedient of direct democracy. He was in the habit of comparing proposals to

adopt direct democratic methods, under modern conditions, with attempts “to

repair or construct a ship of the line made with no theory, and no resources,

beyond those of savages in the construction of their canoes.” Rousseau he

accused of “confusing the principles of the social art with the beginnings of

human society.”

In his views on the seat of authority in the State and

on the origin and end of society, Sieyès was in substantial agreement with

Locke. Like many of those who used the conception of a social contract, he was

not careful to ascertain whether or not the contract was an historical fact.

For him it lay in the future rather than in the past. Rational society ought to

originate by mutual assent; existing societies were so irrational that their

origin might best be attributed to blind accident. “I leave the nations formed

by chance,” he wrote in one of his youthful notes; “I assume that reason is at

last going to preside over the formation of a human society, and I wish to set

down an analytical sketch of its constitution. I shall be told that I am going

to write a romance. I reply, so much the worse; I should have preferred to find

in the actual course of events what I have been forced to seek in the realm of

possibility.” Sometimes he would write as if, even in France, the State had

been founded by contract in historical time; but that is never his true

opinion. He did not stop to ask whether Mably was right, whether the

establishment of the absolute monarchy involved a royal breach of agreement. In

the eye of reason, princes and parliaments received their commission from the

people, from whom alone authority could proceed: that was all he knew or cared

to know. Locke’s reply to Filmer was labour wasted.

Hobbes was a patent ass, who need not even be named: “it would be ridiculous to

suppose that the nation itself could be bound by the formalities or the

constitution to which it has subjected its mandataries.” For neither

prescription nor force had anything to do with right.

Society existed, according to the theory developed by

Locke from Roman origins, to preserve men’s “lives, liberties, and estates,

which I call by the general name of property.” Locke regarded private property,

in the narrower sense, as the product of the labour of the individual and the right to it as anterior to society. This view was not

universally received in France. It stands on record in the Declaration of

Rights, partly owing to Sieyes’ own influence ; but it is a principle of

difficult application in troubled times, when the needs of the State call for

infinite individual sacrifice. For this and other reasons Rousseau and Mably

had argued that the right of property was not anterior to, but established by,

the State. Society could at any moment resume what it had granted. What law

had created law might destroy. On the other hand, Locke’s view had been given a

fresh extension by the economists. They had contended that the relations of man

to property, his economic activities in the widest sense, were best left

absolutely to natural law. Positive law existed mainly to keep the field clear

for the operation of that higher force, and society was good because it enabled

men to “ extend greatly their faculty of becoming proprietors.”

This physiocratic extension of Locke’s teaching

possibly coloured Sieyès’ doctrine of property. He

once called it “the God of all legislation.” In his bitterest attacks on the

nobility, he allowed that the influence derived from their great possessions

was natural and just, though in existing circumstances unfortunate. And he

maintained, throughout his whole career, that only those who were in a position

to make some small direct contribution to the national taxes should be allowed

to take active part in public life. He hoped, as will appear, to exclude in

this way but a tiny minority of destitute persons “without stake in the

country”; but he clung to the principle that the full citizen must be in a

position of decent economic independence, must have his share of the good

things whose enjoyment the State defends. The mass of his philosophic

predecessors or contemporaries went vastly further in this direction—Voltaire,

who said that the man without land or house of his own must have no voice in

the conduct of government; d’Holbach, with his

aphorism “the soil makes the citizen”; Turgot, who defended a stiff property

qualification for electors; Condorcet, who as late as 1788 would have refused

full political rights to all those who could not live from the yield of their

own lands ; Mably, who, in a posthumous work, with true classical contempt for

men whose only property is the skill of their hands, asked his readers to

admire with him “the Author of Nature, Who seems to have destined, or rather

Who actually has destined, this scum of humanity to serve, if I may so put it,

merely as ballast to the vessel of society.”

There is some reason to think that Sieyès, in spite of

his phrase about the God of legislation, would from the first have looked with favour on a judicious redistribution of the land, a thing

of course quite compatible with respect for the political significance of

ownership. He always wanted to break the power of the privileged classes, and

that was not easy without a certain disregard of proprietary rights. In his

very systematic Exposition of the Rights of Man, he draws a sharp line between

landed and other property. There is no complete explanation, but the phrase

employed suggests that he reckoned the distribution of landed property so vital

a matter, that interference with a manifestly harmful distribution would be

equitable. Perhaps he did say, as a memoir writer tells, that what he wanted

was not “to destroy property, but to change the proprietors.” Per contra,

it must not be forgotten that he more than once resisted the reckless treatment

of property by the National Assembly, and that he would certainly never have

approved a scheme for redistribution without some measure of compensation.

Of liberty he held with Montesquieu that it “can only

consist in the freedom to do what one ought to will, and in the absence of any

constraint to do what one ought not to will.” Men are free, Sieyès maintained,

when they learn to regard one another not as obstacles in each other’s way, but

as means to increase one another’s happiness. So the existence of organised society weakens no man’s power to increase his

own and the general happiness by intelligent co-operation with his fellows. By

entering into society man “does not sacrifice part of his liberty. For, even

out of the social state no one can possess the right of doing harm to another.”

Here Sieyès parts company with Locke, who represented man as sacrificing on his

entry into society a real, though uncertain and dangerous, freedom for a lesser

freedom and a greater security. Sieyes’ doctrine differs also from that of

Rousseau. In the Social Contract the advantages of society are dwelt on with

far more apparent appreciation than in the Treatise of Civil Government. Apart

from the social bond, man is conceived of as non-moral and animal; yet the

transition from nature” to society is spoken of as involving real loss.

Neither of these points is adopted by Sieyès.

Whether that preservation of liberty and property for

which society exists is realised or not depends upon

the Constitution. If it is to be binding, the Constitution must be a deliberate

product of the national will, constructed by a representative body assembled ad

hoc—a convention. In 1789 Sieyes wished the improvised National Assembly to

declare that its strictly constitutional legislation required the endorsement

of some such body. But he never believed in the plebiscite, since he rejected

Rousseau’s view that “ the sovereign people, which is a collective being, can

be represented only by itself,1 and shared Mably’s intense dislike and distrust

of the direct rule of the crowd.

Representation was in fact the first principle, the “single and common spring,” of Sieyes’ system. “Everything is representation in

society”; outside of it “there is nothing but usurpation, superstition and

folly.” He held that the application of the representative principle to all

sides of national life was “the real object of the Revolution.” From a

representative system, skilfully contrived, France

was to derive all the benefits that other thinkers had connected with direct

democracy, benevolent despotism, or mixed government. He did not regret the

lost youth of the world, for he knew how to unite liberty and self-government

with empire. Most of his contemporaries stood for representative government,

but his faith in the cause was unique. Through representatives the Constitution

is made or accepted. By representatives alone is legislation carried on. There

is no room—as Mably had held—for any veto, least of all for a veto by the

crowd. By complicated devices, property is to be “represented,” without adding

to the voting power of the individual property holder.1 These devices involved

indirect election, a system that Sieyes defended for its own sake, on the

supposition—shared by the framers of the American Constitution—that it would

produce a type of representative distinctly superior to the ordinary directly

elected person. In no case is the representative to be a mere vote-carrier; he

is a trusted citizen chosen by an elaborate system to fulfil the social

function of law-making. Sieyes saw clearly that Mably, the disbeliever in

direct democracy, was inconsistent when he wrote that the greatest of all

political dangers was that the deputy should fancy himself endowed “with any

authority of his own, and so betray ” the interests of his constituents. In Sieyès’

eyes the deputy existed to exercise authority over the making of the law, and

the mechanism of representation that he devised was meant to exclude the

possibility of binding instructions issued by constituencies.

It was easy for him to ignore Rousseau’s well-known

attack on the representative system. “The notion of representation is modern:

it comes to us from feudal government,... In the ancient republics, even in the

ancient monarchies, the people never had representatives ; the word was not

known.” “As soon as a people adopts representatives, it is no longer free; it

no longer exists.” The shafts glance off Sieyes’ armour.

He agreed that feudalism was stupid, but an institution was not necessarily

stupid because it was feudal. If the ancients had not hit upon the

representative system, so much the worse for the ancients. The historical

origin of the system was a matter of perfect indifference.

In order that law-making may never slip from the

trusted and chosen hands, the legislative assembly must never die. To preserve

its continuity there are to be no general elections, but each year one-third of

its members are to be replaced.

All servants of society, and not only legislators, are

to be trusted and chosen. No one is to fill any post under Government whose

name is not found on a “ list of eligibility,” drawn up by those over whom he

is to exercise authority or by their representatives. Probably Sieyes got the

notion from D’Argenson, who had suggested that local

government should be entrusted to officials chosen by the royal Intendants from

lists of local nominees. But who pricks out the names on Sieyes’ list ? In the

scheme of 1789 it is of course the King or his agents; for at that time the

Abbe was proposing to leave executive power in the hands of the “hereditary

representative of the nation.” But if he had written a treatise on politics in 1787,

it is very likely that he would have crowned his ideal State with an elective

president. He tolerated hereditary monarchy in ’89 and later for reasons of

expediency, but he never argued with any vigour in

its favour. Once, in a footnote to an early pamphlet,

he said that “kings had become hereditary to avoid the civil troubles that

their election might produce”; but the sentence is introduced by an “if” and

is part of an argument against the extension of the hereditary principle to

legislation.1 With Locke he was strongly of opinion that the legislative is “the supreme power of the commonwealth.” He never meant to entrust any share in

legislation to the King, as in England. He was shrewd enough to know that an

hereditary monarch, recently absolute, would not squeeze easily into the narrow

niche provided for him. But if the King would honestly try, Sieyes would not

make the feat more uncomfortable than was necessary.

That his projected political machinery might work smoothly

it was essential that France should be redivided and subdivided upon a uniform

plan. The scheme was in the air during the eighties, and map-makers were at

work upon imaginary redivisions, but Sieyes was to become its best-known

advocate and to leave upon it the stamp of his own mind.

When the representative system had been completed in

all its parts, the time would be ripe for measures of legal, administrative and

social reform whose results would prove permanently beneficial. Until its

establishment there was no guarantee even of the rudiments of civil liberty, in

France or any other country, and reforming legislation might prove labour lost.

This whole scheme of highly organised representative government has more points of contact with the Constitution of

the Commonwealth of Harrington’s Oceana than with any plan put forward in the

eighteenth century. Oceana had its permanent legislature, renewable by thirds

yearly, a system, as the Lord Archon once explained, which caused “the House

(having at once Blossoms, Fruit half ripe, and others dropping off in full

maturity) to resemble an Orange-tree.” Though there were two chambers—both

elective—the power of accepting or rejecting laws lay absolutely with one:

there was no veto. The fruit for this parliamentary orange-tree was selected by

indirect methods. Legislators were not delegates, but law-makers with full

authority. For purposes of government Oceana was split up into uniform

provinces, as England and Wales would have been if Harrington had had his way.

To him the redivision of the country, “with as much equality as may stand with

convenience into fifty shires,” had seemed a wise device for ensuring “that the

people may be most equally represented or that the Parliament may be freest.” Lastly,

Oceana had no room for hereditary political power, and its Archon was wont to criticise the older English Constitution much as Sieyes criticised the England of George III. —“Your Gothic

politicians seem to me rather to have invented some new ammunition or

gunpowder, in their King and Parliament, than Government... Where are the

Estates or the power of the people in France ? Blown up... On the other side,

where is the King of Spain’s power in Holland ? Blown up.” Sieyes would have

agreed that the pretended balance of power between King and Parliament was no

real balance, that the system only worked smoothly when one or other was more

or less completely “blown up”; and he had no wish to experiment with these

political explosives in France.

That he had studied Harrington may certainly be

assumed. Assumption is needed because we happen to know at first hand the names

of only four authors whom he had read. But a knowledge of Harrington was taken

for granted among those interested in political theory in his day, and it was a

matter of common gossip that he had borrowed the idea of the uniform

departments from Oceana. There was no

need to go to Harrington for the idea in 1789 ; but it is interesting to find

that the first time Sieyes put it forward, the number which slipped from his

pen was fifty. A round number taken at random perhaps; but its occurrence in

the text, close to the plan for an orange-tree Parliament, suggests a copy of

Oceana somewhere on the author’s table. And when, later in life, he had to

revise his theory of Parliament, there is every reason to think that he again

drew inspiration from Harrington.

From the fundamental parts of his earlier pamphlets,

speeches, and legislative proposals, and from the few records of his prerevolutionary

opinions which have survived, it is not difficult to reconstruct his system.

Some of his best-known and most striking constitutional devices first come to

light at a later date, and though their connection with the original body of

doctrine is usually organic, though they are at times but the working out of

hints dropped early in his public life, they show traces—more and more marked

as the years go by—of his bitter experience in the Revolution, until at last

the distance between principles and proposals becomes so wide that the

proposals have seemed to many a parody of his original creed. One is not

justified in assuming that any scheme put forward after 1794, which is not

clearly foreshadowed in his earlier work, was part of the primitive system.

That the system as described was finished and coherent before 1789 will be

plain when the details of the first scheme of constitutional reform have been

examined. But as all our knowledge comes from documents drawn up to serve some immediate

end, there are fundamental matters upon which no full and clear profession of

faith has been preserved.

What, for instance, did Sieyès think should be the

place of women in the State? Several times in his 1789 pamphlets he showed

discontent with the traditional solution. He even expressed a definite wish

that woman should be admitted to the franchise.1 But he took no part in the

controversy on the question raised by his friend Condorcet in his article Sur l'admission des femmes au droit de cite of July 1790. Nor did Sieyèsever return

to the subject. Probably he continued to admit the right, but was not ready to

spend labour to no purpose in defending it.

Had he a philosophy of the majority, a satisfactory

answer to the question—By what right, if any, is the opinion of a majority

treated as an expression of the general will, supposing there to be a general

will? Probably not. The defence of decision by

majority in his Exposition of the Rights of Man is as unsatisfactory as most

other defences, save the humble argument from

convenience, an argument which Sieyes himself adopts elsewhere. It is dominated

by the barren conception of a tacit contract among persons working towards a

given end, a contract by which they agree to uphold whatever means the majority

may adopt for gaining that end. He was not apparently interested in Rousseau’s

doctrines of the general will. Had he concerned himself with them, he would

probably have labelled them superstitious. His official view of the universe

was mechanical, and his favourite metaphor, natural

enough in the mathematical age, was not the social organism, but the social

machine. Yet he did not think, or rather he did not feel, that France was a

machine devised to secure the happiness of Frenchmen. Passionately patriotic,

sentiments of which he gave to himself no reasoned account broke all the bounds

of the mechanical individualism that he ordinarily professed. He acted as though

France were a moral person, with a life and interests of her own, greater than

the lives and interests of the individuals who at a given point in time

composed French society. But in argument, he would probably always have said

that phrases such as the will of France, the interests of France, were merely

metaphorical. However that may be, his system of government was well calculated

to ascertain the general will as conceived by its modern exponents, who tell us

that it is more likely to be discovered by an appeal “to the organised life, institutions, and selected capacity of a

nation,” than by any appeal “to that nation regarded as an aggregate of

isolated individuals.”

To name but one other gap in our knowledge of his

opinions—we know little directly of his views on Federalism. As his system did

not require a world full of small states, he lacked the faith that drove

Rousseau to follow Montesquieu in admiration for federal republics. Neither Sieyès

nor anyone else had taken seriously the suggestion thrown out by Helvetius,

himself not half in earnest, that France should be cut up into thirty little

republics, united by strict confederation, each guaranteeing the territory of

all its neighbours. During the Terror the charge of sympathy with such teaching

became a death warrant, but no enemy could ever bring that charge against

Sieyes. The most that he had ever done was to suggest that the French colonies

might have Parliaments of their own and a federal relation with the mother

country. In him the feeling that was to coin the phrase “the Republic one and

indivisible” was overwhelmingly strong; he and those who thought with him

never drew from the current social philosophy, save sometimes in words and for

foreign consumption, that denial of the claims of historical nationality which

was common among the more speculative Germans, who had forgotten what it was

to be at one.

It is singular that a man of Sieyes’ temperament, knowledge,

and literary ability, should never have printed a single page until he was

turned forty, when the coming of the Revolution provided a compelling motive.

One is tempted to think that, more clearly than others, he saw change coming

from afar and waited. The position that he himself was to secure among the

makers of change he cannot have foreseen. Yet he assuredly dreamt of exerting

influence, and great influence, by voice or pen. Thinkers before him, standing

in the classical tradition, had taught that a new system of government is most

likely to succeed when it is the product of a single man of supreme ability,

for then it will be consistent in all its parts. It is not a teaching that

should attract a wholehearted believer in representation; but it certainly

attracted Sieyes. He thought ill of the men of his own day, of their capacity

and their character. He was a reformer because the chaos of society jarred on

his sense of the necessary harmony of things, as a discord jarred on his ear;

because he had himself felt the weight of the dead hand; because he saw

unreason in high places and reason made tongue-tied by authority—only to a

lesser degree because he was moved by sympathy for individuals or indignant

that the law should grind the faces of the poor. The social machine had to be

recreated after a fresh model. And he was the wise mechanician fitted to

superintend the work. That clumsy old structure had turned out bad stuff—recall

his psychology—which a slightly soured philosopher might reasonably contemn.

Representation would only have its perfect work among the nobler and happier

products of the new mechanism. And how were they to be produced at all unless

the right man drew the plans ?

|

||

|

|