|

MODERN HISTORY LIBRARY |

|

|

CHAPTER

III.

FRENCH

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY LITERATURE AND ITS EUROPEAN INFLUENCE.

The literature of France in the seventeenth century

has always been regarded, both by other European peoples and (with the

exception of a few writers whose influence is not perhaps of much weight) by

the French themselves, as most thoroughly representative of the literature of

which it forms part.

In no other

period have the distinguishing characteristics of French intellect and

genius—method, logical sequence of ideas, and lucidity of style—been so

conspicuous. The classical tradition of Greece and Rome, followed by the great

poets and prose-writers of the sixteenth century, with a zeal as overmastering

as it was injudicious, and transmitted by them to those of the seventeenth,

was handled by their successors with so fine an insight, so sure a sense of

proportion, and so instinctive an art of combining national originality with

the inspirations of classical tradition—in short, with such felicity and

propriety and skill—as to have resulted in a success almost unparalleled in the

whole history of literature.

Innumerable

influences were intermingled and interwoven at this period of literary

workmanship; but three of them, at least, proved so strong, so striking, and so

continuous throughout the whole of the century, that a kind of authoritative

rank ought to be assigned to them. These are the influence of Montaigne, that

of Malherbe, and that of Descartes.

By virtue of

the power which Montaigne exercised, he belongs rather to the seventeenth than

to the sixteenth century. Every seventeenth century man of letters read his

works incessantly and was deeply imbued with their spirit. In all these writers

are to be found deep traces, echoes, imitations, and even plagiarisms, of

Montaigne. It is a striking indication of this all-pervading influence that the

two chief representatives in the seventeenth century of whatsoever in it was

most Christian and most Catholic, the two most deeply religious men of the age,

and therefore those furthest removed from the spirit of Montaigne—that is to

say, Pascal and Bossuet—found Montaigne as it

Although

Montaigne represented the classical tradition in perfection, and borrowed from

it all that was most refined and best suited to the French mind, he himself

represented, or it might even be said evolved, the true French spirit. From him

his compatriots learnt delicacy of treatment, and derived the taste for a

searching but dexterously and gracefully conducted analysis of ideas, together

with their love of the study of characters, pursued with ardour but not without

the sure touch of the master’s hand—in short, every tendency proper to the

humanist and the moralist who is at the same time a man of genius. The

literature of the seventeenth century, which concerned itself almost

exclusively with the study of man, owes its bent in large measure to him. In a

word, Montaigne might almost be described as the literary father-confessor of

the seventeenth century.

Descartes,

himself a moralist (for we must not forget his marvellous Traité des Passions),

bestowed on the seventeenth century those qualities which Montaigne either

naturally lacked or did not deign to acquire—careful arrangement, a sense of

order, the rectilinear sequence of ideas, the art of boldly tracing the grand

outlines of general conceptions with a sure touch and a master-hand. Teacher, in

this respect, of Bossuet, of Bourdaloue, of Boileau, even of Molière and of

Racine, as well as of Malebranche, he mapped out the high-roads along which the

French intellect was to travel; had Montaigne been the only writer to exercise

a controlling influence over French minds, they might, perhaps, have become too

much attached to winding by-paths; had Descartes been the sole influence, they

might have fallen into the habit of keeping to the high-road. Thus, it is

fortunate that one of those two great personalities revealed the charm of the

labyrinths of literature through which the visitant strays, not however

dropping the thread from his hand, while the other grandly opened out the royal

highway straight through the forest intellectual.

Last,

Malherbe, following in the footsteps of Ronsard, but with none of Ronsard’s

defects, taught Frenchmen, first of all, the use of plain, clear, and concise

language, which had rejected everything superfluous and bore no trace of

piecing; more especially, he taught them rhetorical poetry, eloquence clothed

in noble verse, the amplitude and the movement of stately sentences. He taught

the French to become perfect orators in verse as well as in prose; for we learn

from poets how to write prose; and his influence, which, in a measure, had long

been latent, made itself felt to an enormous extent throughout the

In Montaigne,

then, we find a delicacy of diction which is full at the same time of grace and

of strength; in Descartes order and strength in composition; in Malherbe a sure

and expressive oratorical form : and in one and all we find reasonableness.

These qualifies in combination formed the essence of the classical French of

1660, which in its turn has exercised so profound and, all things considered,

so salutary an influence on the different literatures of Europe.

The School of

1660 included at least a dozen writers of the first rank, each with his

own distinctly defined originality, but each possessing qualities common to

all, and each exhibiting close affinities to the rest. Only a few of the chief

among these writers can be here mentioned and characterised.

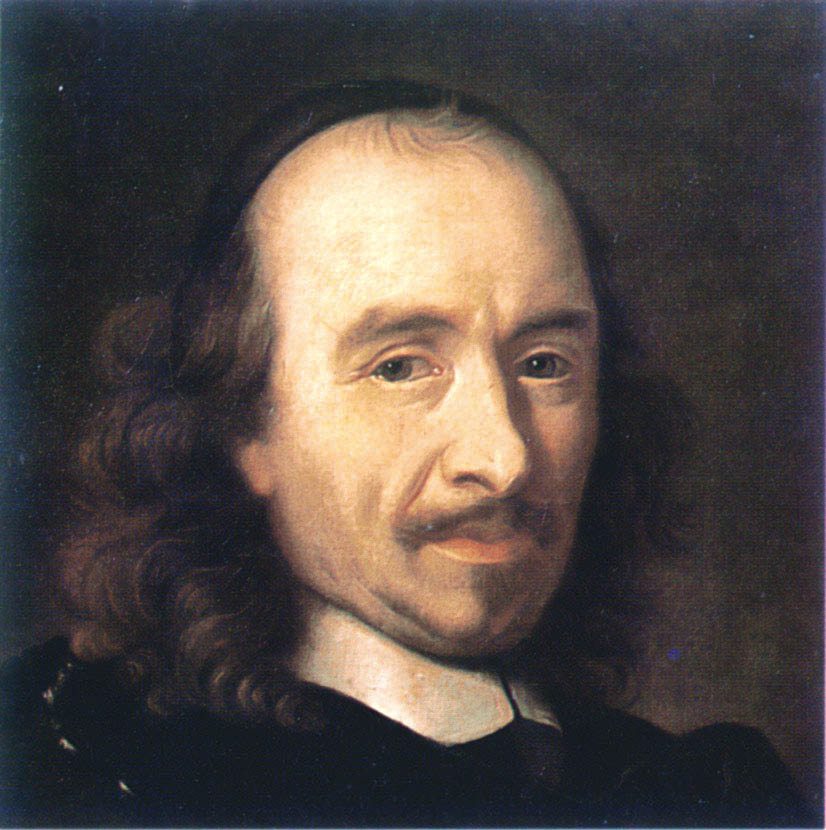

The Classical School: Corneille.—Bossuet. Corneille,

who, however, preceded the others, and who only belongs to this group in the

sense in which a father belongs to his family, was as much of a Stoic as was

Montaigne; but, although he took delight in posing as such, he was, in

the main, the poet of that doctrine of free will, of which Descartes was the

convinced and eloquent exponent. Corneille sang of magnanimity, of loftiness of

soul; though he was not thereby prevented from frequently drawing base and vile

characters, or from displaying singular penetration in the analysis of complex

individualities. But he is preeminently the poet of the human will. He

pourtrays man struggling against the blows of Fate and prevailing against them,

by means of his trust in himself and in the inward strength with which he feels

himself endowed. He depicted those “warrior souls” whom Bossuet was later to

call to mind; and at his bidding there passes before our eyes a long procession

of combatant spirits. Corneille remains the very type of those artists who

aspire towards the things that are great and who hold that the highest kind of

beauty is to be found in the beauty of holiness.

Bossuet

pressed the most powerful eloquence, and a “verbal”, but yet

disciplined, “vehemence” into the service of the religion he expounded.

The impetuous

arguments with which he stormed the enemies’ citadel were

tempered by order and

method, and each was advanced in its own place and season.

Indeed, he conveys

the impression of a general who has weighty and powerful

forces under his

control, which he pushes to the front with equal rapidity and

precision, in an

assault that never breaks the ranks or mars the symmetry of

their lines.

La Fontaine.—Boileau.—Molière.

La Fontaine,

the most self-contained and original of the poets and indeed of all the writers

of the seventeenth century, owes little to Montaigne, little to Malherbe,

although he loved him greatly, and

Boileau is, strictly

speaking, the pupil of Malherbe, and—whether for better or for worse, just as

one may view it—a pupil turned teacher, a pupil, that is to say, who fears to

go further than his master and shrinks from nothing so much as from being

original. Possessed of wit, especially of that satirical wit which is not the

highest kind, he had good judgment, a logical mind and even eloquence; he knew

how to draw a portrait or at least how to block out a sketch; his style, when

defining literary precepts, was clear and fairly powerful; he discoursed on

questions of morals as one possessing authority and capable of some emphasis;

and he could be carried away by feverish indignation in rebuking an indifferent

writer. He ought to be, although he probably is not, the idol of the “Aesthetic

School,” since he exhibited against the writers of other Schools than his own a

spirit of indignation which found its vent in invective such as is usually

reserved for criminals. Thus he possessed all the qualities, together with the chief

failing, of men of letters.

Everything

that can be said about Molière has been said—as to his wonderful gift for

making even the most complex of his characters alive and real, until their

conversation and even their very gestures have become proverbial; his comic

power, or, in other words, his art of arousing, and of at the same time

satisfying, more and more fully as he proceeds, the interest of curiosity

seasoned by malice; his depth of conception, which is a very different thing

from close observation of life, and which consists in the creation of

characters capable of being viewed from ever fresh standpoints, and possessing

an inexhaustible interest for those who subject them to analysis, so that they

offer a new revelation to readers of each successive generation. But it has not

been sufficiently pointed out that, like Corneille, like Boileau and like La

Bruyere at later date, Moliere has often, indeed almost always, the dogmatism

of a preacher;

Racine.—Influence on German literature.Finally (for

we must not unduly prolong this rapid survey) Racine showed throughout his work

what Corneille showed only on occasion, that he was a delicate and subtle and

profound painter of the passions. It is true that, strictly speaking, he only

studied the three passions of love and jealousy and ambition; but he treated

these with great skill in all their devious movements, he traced their

development, and he depicted every shade in their operation, even the most

fleeting, without, however, losing himself in a maze of detail, and never

forgetting the broad outline. Hence his gallery of living portraits, admirably

managed from the point of view of technique, which time will never obliterate

or change or tarnish.

These great

men were the admiration of all Europe in their day, and they exercised a very

powerful influence over the European literatures of their times. In Germany

this influence lasted for nearly a century—from the Thirty Years’ War until

the middle of the eighteenth century. Mention must be made of Martin Opitz,

who, copying the example of his

Dutch master Daniel Heinsius, had imbibed the leading principles of French

literature in such a degree as to earn for himself the name of the “German

Malherbe”; he was a pronounced partisan of the system of imitation, and, far

more like Ronsard than Malherbe, he strove to introduce into the literature of

his own country the distinguishing beauties of every other literature.

We should

also mention Fleming, who imitated the French, especially where they in their

turn had borrowed from the Italian School;— Andreas Gryphius, a

rather florid copyist of Corneille, a writer who, had he been French, would

have found an acknowledged place between Rotrou and Ryer; the various imitators

of the French Romances of the first half of the seventeenth century—imitators

who really derive more from the Spanish influence in French literature than

from French literature itself. Nor, above all, must we forget Gottsched,

translator of Racine’s Iphigenie and author of The Dying Cato, the German

ultra-classic, who was, at the same time, the most thorough-going of the

imitators of the French School, and also the last, or nearly the last, of these

copyists; and who was speedily dethroned by the National School. And, for a

moment, we feel impelled to call from oblivion the worthy and genial fabulist

Gellert, who derived almost as much inspiration from La Fontaine as from his

own kindly nature, and who thus possessed two excellent sources, from which in

point of fact he might have drawn far more than he did.

But the great

name which dominates the whole of the period from 1650 to about 1750 is that of

Leibniz. He was great enough to need no master; nevertheless, he owed to

Descartes his first incentive, the foundation of his inspiration, more

especially and beyond doubt the very tone of his mind, that wide and tolerant

optimism which runs throughout the whole of his work, and animates it with

confidence and with hope. Leibniz might almost be said to impersonate a French

idea, which after sounding the depths of a German mind, comes forth the richer

and fuller for the experience, while still retaining the distinctive style and

characteristics of its origin.

After him,

Lessing appeared above the literary horizon, who dealt the goût français such a

blow that, after 1760, the influence of French on German literature practically

ceased to exist—a fact which should not be treated as a grievance, since it is

best for every nation to live its own life, both intellectually and morally.

Influence on Italian and Spanish literature.Italy, too,

came under French influence after 1650, having, in its day, exercised an

immense effect upon the literature of France. The Seicentisti, from the middle

of the century onwards, were strongly coloured with French influence. Guidi

bears the stamp of Malherbe, but his style is more inflated; Testi, a faithful

disciple of Horace, also possesses something of the grace of Maynard and of

Racan; Chiabrera, “the Italian Pindar”, learns lessons from the French poets

rather than copies them; but his confirmed habit of imitating the classics is

very evidently traceable to French influence, and his pupils, Filicaya and

Menzini, followed the same course, perhaps almost too faithfully. Finally, in

1713, Italian tragedy, after keeping silent long after the profound slumber in

which it had been sunk during the whole of the seventeenth century, was

reawakened by the inspiring touch of the Merope of Maffei, who was, like

Voltaire, one of the most brilliant pupils of the French tragic writers of the

seventeenth century.

The Spanish

writers of the seventeenth century scarcely borrowed anything from the French;

it was rather the French who imitated them. But, from the beginning of the

eighteenth century, it might almost be said that Spain was a pupil of the

French School. To Ignacio de Luzan y Guerra, the disciple of Descartes and of

Port-Royal, Spain owed the Logic of Port-Royal, and he also introduced Milton

to his countrymen; Moratin wrote both tragedies and comedies entirely in the

French style; Cadalso, after finishing his student days in Paris, imitated the Lettres Persanes in his Cartas Marruecas, and Voltaire in his tragedy Don

Sancho Garcia; Jove Llanos, who also translated Milton, produced in the same

epoch on the Spanish stage his tragedy Pelage, written on French lines. Spain

had to wait until the nineteenth century before she again reverted to her own

literary idiosyncrasy— which (assuredly in no sense to her discredit)

altogether differs from that of the French nation.

Influence on English literature.Finally, from

1700 onwards, England came under French influence in a very clear and

unmistakable manner. Addison is the pupil of Boileau, more gifted, more

refined, and more brilliant than his master, but still never forgetful of his

master’s teaching. Moralist, satirist, and critic, a poet equally at home in

the romantic, allegorical, and tragic styles, he could turn with ease from

French wit to English humour, and often seems even to combine, mix and blend

the two together. Taking everything into account, we find Addison so

exquisitely French in his methods that we are often tempted to say of him as

Valentine of Milan said of Dunois: “He was stolen from us.”

Pope, who has

inevitably been much imitated in France, owed much to her in his earlier days.

The style and manner of his letters remind us of Balzac and of Voiture; his

moral poems have the precise turn of wit characteristic of Boileau; he

represents, as it were, the transition between Boileau and Voltaire; moreover,

the Dunciad reads as though it were copied from the Lutrin, the evident

relationship between the two poems being shown by their close similarity of

style.

These great

names must be supplemented by those of Waller, the friend of Saint-Évremond

and the correspondent of La Fontaine, in whom we might almost say was revived

all that was finest in our witty preckux of the seventeenth century; Garth, the

amusing humorist, who recalls the French burlesques, and whose works Voltaire

so highly appreciated as to translate some of them; Arbuthnot, Gay, Lord

Bolingbroke, Lord Chesterfield. The name of Swift may be omitted from the list,

inasmuch as, in the first instance, if he borrowed at all from the French, it

was rather from the writers of the sixteenth than from those of the seventeenth

century, and, secondly, because Swift’s was too original and too individual a

nature to allow of his being cited as an example of any kind of external

influence. But here it is necessary to stop—in view of the well-known fact

that, if the English humorists of the early eighteenth century certainly owe

much to the French, the English “Sentimentalists” of the middle of the

eighteenth century no less certainly exercised a very strong and deep influence

over Diderot, Rousseau, and Sedaine.

This

outline—for it is nothing more—indicates the general characteristics of the

great French writers of the seventeenth century, who made themselves heard and

felt throughout the European world of letters of that century and the earlier

years of its successor. It was a glorious era in French history, however

diversely it may be regarded according to the national standpoint of the

student; as had been her lot in the thirteenth century, so again in the

seventeenth France was unanimously acclaimed the intellectual sovereign of

Europe, all eyes being turned towards her, and all ears listening for her

action.

The

predominant influence of French literature is everywhere perceptible; for a

time its prestige blocked the way and arrested the action

It may be

(for on these inevitably obscure and extremely complex matters it is better not

to dogmatise) that contact with a foreign influence enriches, in a general

way, the national literary sense; or, again, certain sides of the national mind

which were unaware of their own existence or at all events hardly suspected it

may awake and become conscious of their existence when they recognise

themselves in the literature of a foreign land; or, yet again, the real essence

of a nation’s intellectual life may be distilled and acquire fresh strength by

the very reaction against a foreign literature that has for a time been

injudiciously worshipped; and in this case, too, good arises, though

indirectly.

For example,

English humour will endure for all time; but we have seen that it was developed

to a singularly high degree in England after contact with French wit; and

again, in Germany, the national revolution brought about by Lessing and the

great literary results that ensued for German literature were stimulated by

French influence, which not only invigorated German wit, but incited it to the

assertion of its own independence.

We are reminded of the saying of La Bruyère concerning strong and sturdy children who fight their nurses. Nurses give sustenance to their foster-children for the very purpose of making them strong and able, if need be, to fight their foster-mothers. They perform this task in perfect consciousness, and cheerfully undertake the risk which it implies. Whatever the explanation may be, for nearly a hundred years France occupied a position towards every other European nation analogous to that of a nurse; and, on the whole, she cannot assert that, when she remembers this experience, it is wholly unsatisfactory to her.

Lear H.L. Sidney Bossuet and his contemporaries.

Ella Katherine Sanders Jacques Bénigne Bossuet; a studyMolière: His Life and His WorksCorneille and Racine in England: a study of the English translations of the two Corneilles and Racine, with especial reference to their presentation on the English stageLa Fontaine and other French Fabulists

|

|