|

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

THE birth and death of worlds are ephemeral events in a cycle of astronomical time. In the life history of a stellar system, of a planet, of an animal, parallel periods of origin, exuberance, and of extinction are exhibited to our experience, or to our understanding. Man, in his material existence confined to a point, by continuity of effort and perpetuity of thought, becomes coequal and coextensive with the infinities of time and space. The intellectual store of ages has evolved the supremacy of the human race, but the zenith of its ascendancy may still be far off, and the aspiration after progress has been entailed on the heirs of all preceding generations. The advancement of humanity is the sum of the progress of its component members, and the individual who raises his own life to the highest attainable eminence becomes a factor in the elevation of the whole race. Familiarity with history dispels the darkness of the past, which is so prolific in the myths that feed credulity and foster superstition, the frequent parents of the most stubborn obstacles which have lain in the path of progress.

The history of the past comprises

the lessons of the future; and the successes and failures of former

times are a prevision of the struggles to come and the errors to be

avoided. The stream of human life having once issued from its sources,

may be equal in endurance to a planet, to a stellar system, or even

to the universe itself. The mind of the universe may be man, who may

be the confluence of universal intelligence. The eternity of the past,

the infinity of the present, may be peopled with races like our own,

but whether they die out with the worlds they occupy, or enjoy a perpetual

existence, transcends the present limits of our knowledge. From century

to century the solid ground of science gains on the illimitable ocean

of the unknown, but we are ignorant as to whether we exist in the dawn

or in the noonday of enlightenment. The conceptions of one age become

the achievements of the next; and the philosopher may question whether

this world be not some remote, unaffiliated tract, which remains to

be annexed to the empire of universal civilization. The discoveries

of the future may be as undreamt of as those of the past, and the ultimate

destiny of our race is hidden from existing generations.

In the period I have chosen

to bring before the reader, civilization was on the decline, and progress

imperceptible, but the germs of a riper growth were still existent,

concealed within the spreading darkness of medievalism. When Grecian

science and philosophy seemed to stand on the threshold of modern enlightenment

the pall of despotism and superstition descended on the earth and stifled

every impulse of progress for more than fifteen centuries. The Yggdrasil

of Christian superstition spread its roots throughout the Roman Empire,

strangling alike the nascent ethics of Christendom, and the germinating

science of the ancient world. Had the leading minds of that epoch, instead

of expending their zeal and acumen on theological inanities, applied

themselves to the study of nature, they might have forestalled the march

of the centuries, and advanced us a thousand years beyond the present

time. But the atmosphere of the period was charged with a metaphysical

mysticism whereby all philosophic thought and material research were

arrested. The records of a millennium comprise little more than the

rise, the progress, and the triumph of superstition and barbarism. The

degenerate Greeks became the serfs and slaves of the land in which they

were formerly the masters, and retreated gradually to a vanishing point

in the vast district from the Adriatic to the Indus, over which the

eagle-wing of Alexander had swept in uninterrupted conquest. Unable

to oppose their political solidarity and martial science to the fanaticism

of the half-armed Saracens, they yielded up to them insensibly their

faith and their empire, and their place was filled by a host of unprogressive

Mohammedans, who brought with them a newer religion more sensuous in

its conceptions, but less gross in its practice, than the Christianity

of that day. But the hardy barbarians of the North, drinking at the

fountain of knowledge, had achieved some political organization, and

became the natural and irresistible barriers against which the waves

of Moslem enthusiasm dashed themselves in vain. The term of Asiatic

encroachment was fixed at the Pyrenees in the west, and at the Danube

in the east by the valorous Franks and Hungarians; and on the brink

of the turning tide stand the heroic figures of Charles Martel and Matthias

Corvinus. Civilization has now included almost the whole globe in its

comprehensive embrace; both the old world and the new have been overrun

by the intellectual heirs of the Greeks; in every land the extinction

of retrograde races proceeds with measured certainty, and we appear

to be safer from a returning flood of barbarism than from some astronomical

catastrophe. The mediaeval order of things is reversed, the ravages

of Attila reappear under a new aspect, and the descendants of the Han

and the Hun alike are raised by the hand, or crushed under the foot

of aggressive civilization.

In the infancy of human

reason intelligence outstrips knowledge, and the mature, but vacant,

mind soon loses itself in the dark and trackless wilderness of natural

phenomena. An imaginative system of cosmogony, baseless as the fabric

of a dream, is the creation of a moment; to dissipate it the work of

ages in study and investigation. Less than a century ago philosophic

scepticism could only vent itself in a sneer at the credibility of a

tradition, or the fidelity of a manuscript; and the folklore of peasants,

encrusted with the hoar of antiquity, was accepted by erudite mystics

as the solution of cosmogony and the proof of our communion with the

supernatural. An illegible line, a misinterpreted phrase, a suspected

interpolation, in some decaying document, the proof or the refutation,

was often hailed triumphantly by ardent disputants as announcing the

establishment or the overthrow of revelation. But the most signal achievements

of historic research or criticism were powerless to elucidate the mysteries

of the universe; and the inquirer had to fall back perpetually on the

current mythology for the interpretation of his objective environment.

In the hands of science alone were the keys which could unlock the book

of nature, and open the gates of knowledge as to the enigmas of visible

life. A flood of light has been thrown on the order of natural phenomena,

our vision has been prolonged from the dawn of history to the dawn of

terrestrial life, an intelligible hypothesis of existence has been deduced

from observation and experiment, idealism and dogma have been recognized

as the offspring of phantasy and fallacy, and the mystical elements

of Christianity have been dismissed by philosophy to that limbo

of folly which long ago engulfed the theogonies of Greece and Rome.

The sapless trunk of revelation lies rotting on the ground, but the

undiscerning masses, too credulous to inquire, too careless to think,

have allowed it to become invested with the weeds of superstition and

ignorance; and the progeny of hierophants, who once sheltered beneath

the green and flourishing tree, still find a cover in the rank growth.

In the turn of the ages we are confronted by new Pagans who adhere to

an obsolete religion; and the philosopher can only hope for an era when

everyone will have sufficient sense and science to think according to

the laws of nature and civilization.

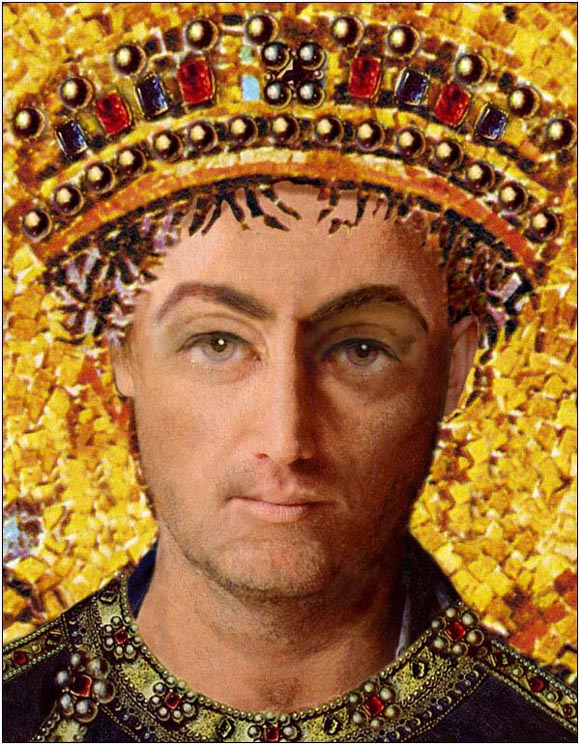

The history of the disintegrating

and moribund Byzantine Empire has been explored by modern scholars with

untiring assiduity; and the exposition of that debased political system

will always reflect more credit on their brilliant researches than on

the chequered annals of mankind.

|

|

|