|

CHAPTER

II

.

THE

FOUNDATION OF THE TANG DYNASTY

AD. 617-18

During

the year AD 616 Li Yuan had been actively engaged in warfare with the Turks,

who, since the siege of Yen Men, had kept up a series of border raids and

sudden forays. In addition, the duke of Tang had been ordered to co-operate

with other governors in the seemingly hopeless task of suppressing the bandits

and rebels who infested the northern provinces.

In

all these campaigns Shih-Min, although only sixteen years old, took a prominent

part. In seventh-century China youths were considered old enough to engage in

politics and war at an age which we now regard as very immature. It is

noteworthy that Shih-Min was not the only boy of his generation who signally

distinguished himself while still in his ’teens. Tu Fu-Wei, the rebel leader in

the Huai valley, was at the head of a large army before he was seventeen. Had

Shih-Chi (Li Shih-Chi) was one of Li Mi’s generals at the same age. Among the

Sui officers defending Lo Yang was Lo Shih-Hsin, who at the age of thirteen led

a cavalry charge against an army of bandits.

It

was an age of youth. The wars and tumults of the time had weakened the heavy

control of the older generation. The Confucian maxims enjoining unquestioning

submission of youth to age were but little observed. The Tang dynasty was founded

by youths triumphing over the fears and caution of a less inspired generation;

following a dismal period of disunion and weakness it dawned as an era of confidence

and hope.

Early

in AD 617, Li Shih-Min, realising that the Sui

dynasty was definitely on the decline, began to consider the possibility of a

revolution. Among the officers stationed at Tai Yuan Fa was Liu Wen-Ching, who commanded

the guard at the imperial palace where Yang Ti had spent the previous summer (ad 615). This officer was related by

marriage to the rebel Li Mi; consequently an order now arrived from the court

for the arrest of Liu, who was to be held in prison till the question of his

complicity in Li Mi’s rebellion was investigated. Liu Win-Ching was a close

friend of Shih-Mio, who came often to visit him in prison. Liu, who now had no

hope of making a career in the Sui service, took advantage of these visits to

urge Shih-Min to plan a revolt Shih-Min already entertained the same ideas; he

now began to canvass his friends, and secretly enlisted soldiers. He did not,

however, mention these activities to his father, Li Yuan.

Li

Yuan, duke of Tang, was an easygoing aristocrat, not remarkably intelligent, a

weak character. He lacked tenacity, foresight and resolution. Had he not been

the father of Shih-Min there was no man living in China less likely to win his way

to the throne. Shih-Min, who perfectly understood his father, knew that he

could never be persuaded to take decisive action unless presented with a fait

accompli. Therefore he kept his plans to himself until the moment was

ripe.

At

this time a curious prophecy was current in all parts of China, to the effect

that after the fall of the Sui dynasty, the imperial throne would pass to a

family of the Li surname. There is no doubt that this prophecy, which proved so

true, was not invented in later years, but really was current under the Sui

emperors, for Yang Ti had one important official family named Li exterminated,

because he believed this clan to be the one indicated by the prophecy. The idea

had obtained such hold an the popular imagination that a group of rebels in Kansu

selected a man named Li to be their leader, although he was not the originator

of the rebellion. Other prominent rebels who owed much of their success to

their names were Li Tzu-Tung, in south-east China, and Li Mi, who was at first

the most popular candidate fin the honours designated

by the prophecy.

Shih-Min

and his supporters may have been influenced by this saying; the young man

certainly used it as an argument when he approached his father with the

momentous suggestion. He began by pointing out the sad state of the empire and

the utter hopelessness of the Sui cause. Then he suggested that his father, threatened

by the tyranny of Yang Ti on the one hand, and the rising power of the rebels

on the other, should save himself by “following the wish of the people, raise a

righteous army, and convert calamity into glory”.

The worthy governor was greatly shocked at his young son’s proposition.

He exclaimed, “How date you use such language! I will have you arrested and handed

over to the magistrates!”. He even picked up a pen to sign the order. Shih-Min

was not impressed by his paternal bluster. Making no apology for his words, he

replied, “I only spoke because, as I see it, this is the true state of our affairs

today. If you arrest me, I am quite ready to die”. His father testily replied, “How

could I think of having you arrested? Never dare to speak like that again”.

The

boy was not deceived by this show of bad temper, which he rightly interpreted

as the instinctive reaction of a weak character faced with a serious decision.

He re-opened the subject the next day. “At present”, he said, “the rebels ate

increasing every day, they have spread over the whole empire. Do you, Sire,

suppose that you can carry out the orders of the emperor and suppress them?

Even if you could succeed, you would still be suspected, and accused of some

crime. Everyone says that the Li name is destined to obtain the empire, and for

that reason the emperor butchered the whole family of Li Chin-Tsai, although

they were guilty of no crime. If you really put down the rebellions your

services would be beyond recompense, and therefore you would go in peril of

your life. The way to escape this danger is to do what I said yesterday. It is

the only way, make no doubt of that.”

Li

Yuan sighed, then replied, “All last night I thought over your words. There is

much truth in them. Now if our family is mined and our lives forfeit, it will

be all your fault; but if we mount to the throne it will be equally thanks to

you”,

Shih-Min,

however, knew his father’s character. Li Yuan might be induced to approve of

the plan, but it did not follow that he would act upon it. The boy therefore contrived

an intrigue which would commit his cautious father beyond escape.

Through

the agency of Lin Wen-Ching, Shih-Min had made friends with Pei Chi,

eunuch-superintendent of the imperial palace at Fen Yang, near Tai Yuan Fu. Pei

Chi became a member of the conspiracy, and his aid was now most useful.

Instigated by Shih-Min, who had studied his father’s pastimes to some purpose,

Pei Chi made a selection of the most beautiful damsels from the harem of the

palace, which was under his control, and presented Li Yuan with these choice

flowers from the emperor’s private garden, without telling the unsuspecting

governor whence they came.

A

few days later the eunuch invited Li Yuan to a banquet, and when the wine had

flowed freely, Pei Chi, feigning a tipsy confidence, remarked, “Your second boy

(Shih-Min) is secretly enlisting soldiers and purchasing horses, no doubt for

‘the Great Affair’. Now that I have given your Grace some of the ladies from

the Fen Yang palace I am afraid that If this news leaks out we will all free a

capital charge. It is really a very serious matter. I think we should all act

together, what is your Grace’s opinion?”

Li

Yuan, astounded, could only stammer out, “So my boy planned all this! If things

are as you say, there is no going back, and I must give my consent”.

The

final argument was supplied by the emperor himself. An officer from the court

arrived at Tai Yuan Fu with an order for Li Yuan, who was directed to travel to

Yang Chou forthwith, to answer for his conduct in failing to suppress the

rebels. No one could doubt that the governor had incurred the fatal suspicion attaching

to all who bore the name of Li. This news was decisive. Li Yuan knew what his

fate would be, if, when he readied the court to report his ill-success against

the rebels, the further capital charge of violating imperial concubines came to

light. It was even doubtful whether he could reach the southern capital at all,

across hundreds of miles of rebellious provinces.

Vehemently

urged to revolt by Shih-Min, Pei Chi and all his officers, the wavering

governor only hesitated long enough to give his eldest and youngest sons, Chien-Cheng

and Yuan-Chi, time to escape from the city of Pu Chou Fu, in the south of the

province, where they were then residing. This city was held by the well-known

Sui general, Chu-Tu Tung, who was loyal to Yang Ti. As soon as these young men

had reached Tai Yuan Fu, Li Yuan assembled his officers, and after going

through the last formality of asking their advice, proclaimed his intention to

revolt.

The

revolution was accomplished without difficulty. Certain officials who had not

joined the conspiracy attempted to organise resistance, but the precautions which Shih-Min had taken rendered their efforts

futile. The day passed easily into the hands of the insurgents. A greater danger

came from a roving band of Turks, who, attracted by the news of the tumult,

attempted to capture the city. But though they invested the walls for some

days, they lacked the means to force so strong a position, and after plundering

the neighbourhood, made off in search of easier

booty.

The

plan of campaign, in the framing of which Shih-Min bore a chief part, had for

its objectives the conquest of Shensi and the rapture of Ch’ang An, the capital

of that province. This plan, it will be remembered, was one of the three which

Li Mi proposed to the rebel Yang Hsuan-Kan, though Li Mi himself did not adopt

it when he had the opportunity. It is a notable proof of the abiding strategic

importance of Shensi that most of the great conquerors in ancient China used

this country as the cradle of their empires. Shih Huang Ti, of Chin dynasty,

the first unifier, Kao Tsu, the founder of the Han dynasty, and Yang Chien the

founder of the Sui, all used Shensi as their base. With the slow change in the centre of gravity of the Chinese state, which has now moved

southward, the strategic importance of the north-west has declined, and the

dwindling population and increasing aridity of this country have robbed it of

its ancient strength. But in the seventh century Shensi was the heart of China.

To

penetrate Shensi the Tang army had to pass the Yellow river, which could only

be reached by an advance down the valley of the Fen, a tributary which drains

the Shansi plateau. The Fin valley was strongly defended by several cities

still loyal to the Sui cause. The first of these obstacles was the city of Fin Chou,

fifty miles from Tai Yuan Fu. Shih-Min and his eldest brother, Chien-Ching,

were sent against that place with the advance guard. Fen Chou made only a

feeble resistance, falling after a few days’ siege. The strict discipline of

the T’ang army, which paid for its provisions and

requirements, made a favourable impression on the

inhabitants of the surrounding country, who submitted without difficulty

Before

advancing farther, Li Yuan was anxious to protect his base, Tai Yuan Fu, by mailing

peace with the Turks. Sibir Khan was not unwilling to

come to terms; indeed he suggested that Li Yuam should at once take the imperial title. The Turk was always ready to support

Chinese pretenders who would weaken the power of the Sui dynasty. He had

already set up two puppet emperors, Liang Shih-Tu and Liu Wu-Chou, who had

accepted Turkish suzerainty. But the duke of Tang realised that it would not do to appear as a Turkish vassal of this type. He therefore

adopted the expedient of declaring Yang Ti deposed, recognising as emperor Yang Yu Prince Tai, a grandson of Yang Ti. This young prince was the

nominal governor of Chang An, the objective of the Tang army.

In

the seventh month of the year A.D. 617, in the middle of summer, the Tang army,

about 30,000 strong, passed unopposed through the Squirrel pass (Chiao Shu Ku),

a position of great natural strength which, had it been guarded, would have checked

all advance into the lower Fen valley. The Sui generals, realising too late their error, hastily gathered 20,000 men to garrison Huo Chou, a city

at the southern end of the pass. Another Sui army was stationed at Pu Chou Fa

in the angle where the Yellow river makes the great bend to the east, a city

which guards the approach to the crossing at Tung Kuan, the gateway of Shensi.

The

Tang army was now held up by lack of supplies and the heavy rains of midsummer.

During this delay negotiations were opened with Li Mi, but that rebel, though

he promised to do nothing to hinder the Tang march, would not commit himself to

open support, preferring to cherish independent ambitions.

The

rains continuing unceasingly, scarcity of provisions in the Tang camp became

acute. At the same time the news that Liu Wu-Chou, the pretender in north

Shansi, was raiding the border and menacing to attack Tai Yuan Fu itself filled

the irresolute Li Yuan with alarm and uncertainty. Supported by Pei Chi and

others of his staff he decided to retire to protect Tai Yuan Fu. At this crisis

the persistence and vision of Shih-Min alone prevented what would have been a

ruinous mistake. Vehemently he insisted that to retreat now would be fatal. The

Sui commanders would have time to assemble a far superior army, while a

retirement would dishearten the Tang troops, encourage their enemies, and above

all remove any possibility of entering Shensi by surprise. He further maintained

that though Liu Wu-Chou might odd as far as Tai Yuan Fu, he could not hold the

country s0 long as Ma I and other border forts were in Tang hands.

In

spite of these trenchant arguments Li Yuan refused to reconsider his decision,

and the troops had actually started on the march back, when Shih-Min, still

unwilling to allow this disastrous move, came by night to his father’s tent. At

first refused admission, he made so great a clamour outside that Li Yuan was compelled to let him in. The youth once more urged his

thesis, declaring that all would be irretrievably lost if the retreat

continued. Li Yuan objected, with the evasion of the real issue habitual to his

weak character, that the orders had already been given and the troops were on

the march. Shih-Min, seeing that his father was weakening, promptly offered to

go himself in pursuit with counter-orders. Then with a laugh and a shrug, Li Yuan

yielded, remarking, “Whether we win or lose will be your responsibility; call

them back if you wish”. Shih-Min and his elder brother, Chien-Cheng, instantly

rode after the army and gave orders to cease the retreat. His judgment was

strikingly confirmed a few days later by the arrival of ample supplies from Tai

Yuan Fu with the news that the threatened invasion by Liu Wu-Chou had never

eventuated.

In

the eighth month, the rains being over, the Tang army advanced against Huo

Chou, a city built in a narrow neck of the Fen valley, which here is bordered

by steep mountains. Li Yuan was afraid that the Sui general would remain on the defensive, effectively blocking the

Tang advance. Shih-Min, who knew the Sui general to be a brave but unsubtle commander,

suggested a plan to draw the enemy out to battle. While the Tang army remained

at a distance, a few horsemen were sent ahead to the foot of the city wall,

where they began to mark out the ground for siege trenches, working in a

leisurely manner as if confident that they would not be molested by the

garrison. As Shih-Min had expected, the Sui general considered this apparent

confidence as a reflection on his courage. Enraged at such contemptuous

treatment of a strongly held fortress he made a sortie at the bead of the full

strength of his garrison.

The

Tang army had been divided into two corps, the larger under Li Yuan and Li

Chien-Cheng was drawn up in sight of the town outside the east gate. The cavalry

under Shih-Min worked round to the south, remaining out of sight of the city till

the battle had been joined. The Sui forces, not troubling to ascertain whether

there were any Tang troops in ambush, advanced resolutely upon the main body,

which yielded gradually before the weight of their attack. When the Sui forces had

thus been led some distance from the city, Shih-Min at the head of the cavalry

suddenly appeared on their flank and rear. The unexpected charge of these

troops, augmented by the counter-attacks of the main Tang force on their front,

threw the Sui line into confusion.

Shih-Min,

plunging into the melée, inflicted great slaughter

“till his sleeves were running with blood” as the historian puts it. At the

height of the battle a cry that the Sui commander had been captured was

raised, and this completed the defeat of the Sui army, which broke into flight.

Their

position on the flank enabled Shih-Min’s cavalry to outstrip the enemy, so that

fugitives and pursuers arrived at the foot of the wall together. The

inhabitants, seeing what was going to happen, had already shut the gates, thus

barring out the flying soldiers. The Sui commander, who in reality had not been

taken prisoner, arrived at the east gate and shouted orders for it to be

opened. But his tone of authority only served to identify him to a band of

pursuers, who rode up before the gate could be opened, and cut off his head.

Profiting by the panic of the defenders the Tong forces carried the city by

assault as the day ended.

The

fall of Huo Chou opened up the lower Fen valley to the Tang advance. The

surviving Sui troops had been incorporated in the victorious army, which

occupied Ping Yang Fu, the second city of the province, without resistance.

Chiang Chou, the next place, was defended by an officer of note, Chen Shu-Ta, a

son of foe last emperor of the southern Chen dynasty, which the Sui had

overthrown. This city was captured after some days of siege, Chen Shu-Ta taking

service with the Tang army.

The

Tang army now entered foe south-west corner of Shansi, the angle of the Yellow

river bend. In this angle stands the strong city of Pu Chou Fu, which covers the

crossing places of foe river. Pu Chou Fu was garrisoned by a large Sui army under

Chu-Tu Tung, one of foe foremost generals of the empire. Instead of trying to

take this strong position the Tang leaders left a covering force to watch Chu-Tu

Tung, while the main army crossed the river farther up stream, opposite foe

city of Han Cheng Hsien.

This

plan was the more likely to succeed as the Shensi bank in this neighbourhood was dominated by a bandit chieftain, with

whom Li Yuan entered into negotiations. The bandit welcomed these overtures,

and crossed the river with a few attendants to swear allegiance to the duke of

Tang. With the co-operation of this irregular, who was appointed a general, the

advance guard crossed the river unopposed and constructed an entrenched camp to

cover the passage of the main body. Chu-Tu Tung, when he discovered that he had

allowed the Tang army to slip past, made a night attack with part of his army

on the Tang covering force, hoping to brush aside this corps and fell upon the

main army before it could finish crossing the river. Although his initial

attack was successful, a timely Tang reinforcement turned the Sui flank. Chu-Tu

Tung was defeated and forced back to Pu Chou Fu, where he was besieged.

The

more cautious advisers of Li Yuan were anxious to capture that city before

invading Shensi, but Shih-Min, who realised that

speed was essential, urged an immediate advance on Chang An, which, he

declared could easily be taken if the Sui armies were allowed no time to

recuperate and raise fresh levies. His view prevailed: while sufficient forces

were left to blockade Pu Chou Fu, the main army took the Chang An road. No

sooner had the Tang army begun its march than many cities in their submission,

while volunteers flocked to the Tang camp “like folk going to market”.

Li

Yuan despatched Chien-Cheng with 10,000 men to

blockade Tung Kuan, the key of Shensi, where the main road from the east passes

through a narrow gap between the Yellow river and high mountains. When this place

was taken no Sui troops from Honan could come to the assistance of Chang An. Shih-Min

headed the advance guard, moving along the Wei river, Li Yuan himself following

with the main army.

At

the outbreak of the Tang revolution in Tai Yuan Fu a message had been sent to

Chai Shao, Li Yuan’s son-in-law, warning him to leave Chang An, where, as an

officer of Prince Tai’s bodyguard, he was stationed. Chai managed to get away,

but as his family could not accompany him without arousing suspicion, his wife,

the Lady Li (Li Shih), Li Yuan’s daughter, took refuge in the city of Hu Hsien,

a few miles south of Chang An, where she remained in hiding. Li Shen-Tung, a

cousin of the duke of Tang, fled to the mountains, where he enlisted a band of

supporters to assist the Tang invasion. The Lady Li did not consider that her

sex should prevent het from furthering the cause of her family. She engaged the

support of a bandit chief, a former Central Asiatic merchant, and leading this

force to the support of Li Shen-Tung, combined with him in an attack on Hu

Hsien. The city was taken after a brief struggle, and this success rallied all

the bandits of the countryside to the Tang standards. These bands, which were

led by proscribed members of the official class, were formed into a regular

army by the Lady Li, who soon dominated the country south of Chang An, capturing

the smaller cities in the Wei valley.

While

his valiant sister was engaging in these exploits, Shih-Min had advanced along

the north bank of the Wei to a point only ten miles distant from Chang An. The

Tang army encountered no teal resistance on this march, while the number of new

adherents who came daily to the camp swelled the army to a strength of 90,000

men. Among these who joined Shih-Min at this stage were Chang-Sun Wu-Chi, his

wife’s elder brother, and Fang Hsuan-Ling, a very able official who became his

chief civil adviser.

After

joining forces with his sister’s army, henceforth honoured with the tide of the “Heroine’s Legion”, Shih-Min invested the western capital

with an army which now numbered 150,000 men. Messages were sent to Li Yuan

urging him to come up to receive the surrender of Chang An, which was not

likely to stand a long siege. In the tenth month, when winter was beginning, Li

Yuan arrived before the city with the main Tang army, now no larger than Shih-

Min’s swollen advance force. After a short siege of only a few days’ duration,

the city was carried by storm and the objective of the first Tang campaign was

achieved.

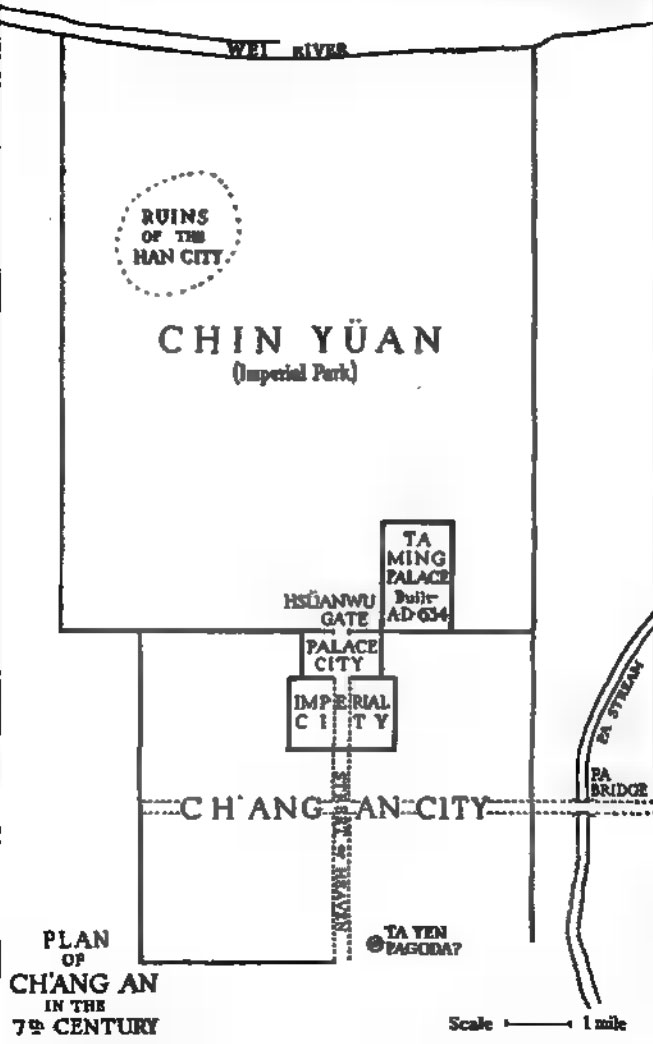

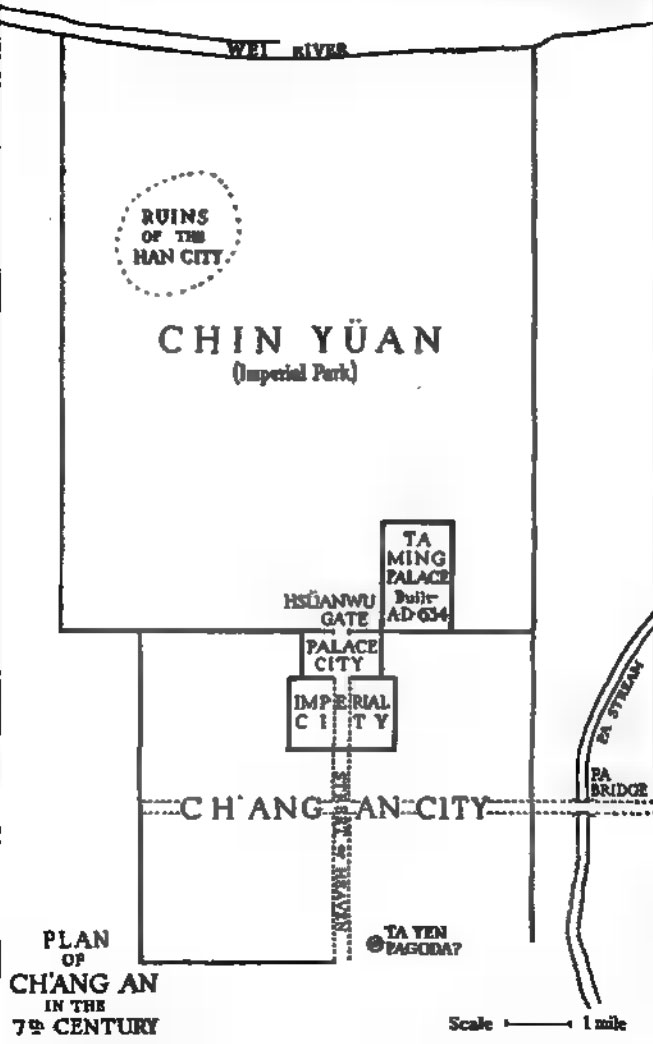

Chang

An, then one of the most populous and magnificent cities in Asia, had recently

been rebuilt by the founder of the Sui dynasty, who had made it his capital.

Yang Ti’s preference for Lo Yang and the south had not yet had time to rob

Chang An of its importance, or to lead to any diminution in its wealth. Under

the Tang dynasty it was destined to become the most famous city in Asia, the metropolis

of the eastern world. The city stands in the valley of the Wei, ten miles south

of the river, and about twenty miles north of the rugged Nan Shan mountains, a range

plainly visible from the city in dear weather.

Today

the undulating plain between Chang An and the mountains is bare, even desolate;

only a few sparse trees marling a tomb relieve the yellow monotony of the loess

fields. Of the parks and gardens, temples and palaces which surrounded the greater

seventh-century city, little trace remains. Beyond the eastern gate the small

Pa river which comes down from the mountains to join the Wei is till spanned by

the famous Tung Pa bridge, a magnificent stone bridge, frequently mentioned in

Tang literature. Three miles south of the present wall the Ta Yen pagoda, which

in Tang times, according to tradition, was inside the south gate, still

dominates the shrunken day.

Ancient

Chang An was indeed far larger than the city of today. Although little of it

remains, a full description has been preserved in Chinese literature. The city,

as rebuilt by the Sui emperor, was, like its successor Peking, divided into

several distinct cities, each surrounded by its own wall. The city of Chang An

proper formed a rectangle, six miles long by five across, having an area of

thirty square miles. On the cast it extended aa far as the banks of the Pa

river, which is two miles at least beyond the present walls. The city was

traversed from north to south by a great thoroughfare, the Street of Heaven,

which was a hundred paces wide, while other important streets crossed this at

right angles. The city was laid out in a symmetrical plan, similar to the design

which the Ming builders of Peking employed eight hundred years later.

In the centre of the north wall the

Palace and Imperial dries formed an enclave. The Imperial City, the more

southerly of the two, contained the government offices and the residences of

nobles and offices. The common people were not allowed to reside in this enclosure,

which had an area of about three square miles. To the north of the Imperial City

was the Palace City, equivalent to the Forbidden City of Peking. This area was

slightly smaller than the Imperial City, being about two square miles. It was the

palace and residence of the Sul and early Tang emperors, before Shih- Min built

the Ta Ming Kung. The Palace city continued to be used throughout the dynasty

on ceremonial occasions such as enthronement

The

north gate of the Palace city, the Hsuan Wu gate, later renamed the Yuan Wu

gate, led into the Chin Yuan or Imperial Park, beyond the walls of the city.

This pleasaunce, enclosed by the Sui emperors, had an

area of no less than sixty-three square miles; on the north it was bounded by

the banks of the Wei river, and it included within its boundaries the ruins of

the old Han city of Chang An. The great park contained an infinity of

pavilions, small lakes, gardens, and miniature palaces, a delicious landscape

garden on the largest scale. Such was Ch’ang An, a vast and splendid capital,

by far the greatest and wealthiest city in Asia.

|

On

capturing Chang An, Li Yuan had issued strict orders that neither the Sui

Prince Tai, whom he affected to recognise as emperor,

nor the inhabitants were to be harmed. Even the Sui officials were left in

peace, except for those responsible for desecrating the tombs of the Li family,

action which they had taken on hearing of Li Yuan’s revolt. These officials

were decapitated. Among those taken prisoner was a certain Li Ching, with whom

Li Yuan had quarrelled. The duke of Tang ordered Li

Ching to be put to death, but the victim indignantly exclaimed, “You pretend to

be the leader of an army pledged to redress the wrongs of the people and

restore tranquillity to the state, and yet your first

act is to seek revenge for a private quarrel by slaying an innocent man”

Shih-Min,

who was witness of this scene, interceded in Li Ching’s favour,

obtained his pardon, and took him into his own suite. In the event Li Ching was

to be one of the most famous generals of the Tang dynasty.

As

Li Yuan was not yet prepared to assume the imperial title, the youthful Yang Yu

Prince Tai, Yang Ti’s thirteen-year-old grandson, who had been the nominal governor

of Chang An, was proclaimed emperor. Li Yuan was rewarded with the title of

prince of Tang, and became minister with plenary powers, and generalissimo,

having charge of all affairs, civil and military. No one, we may be sure, had

any doubt as to Li Yuan’s ultimate intentions, but Chinese etiquette and sense

of legality required a gradual approach to the throne, lest posterity should

reproach the first Tang emperor with the name of usurper.

This

arrangement endured six months, hi the early summer of the next year, a.d. 618,

when news of Yang Ti’s tragic death had been received, the final act was

staged. The boy emperor was induced to offer the crown to Li Yuan. When the

prince of Tang had made the three refusals demanded by Chinese etiquette, and

the Sui monarch had thrice insisted, Li Yuan formally assumed the imperial

dignity. The Sui prince retired into peaceful obscurity. He did not live to

enjoy this sheltered existence for long, but died in the next year, ad. 619. The cause of his early demise

is not stated by the historian; whether it was natural, or assisted, must

remain unknown.

After

Li Yuan had ascended the throne with the accustomed ceremonies and rejoicing,

titles and rewards were distributed to all who had played a part In the great

undertaking. Chien-Cheng, Li Yuan’s eldest son, was proclaimed crown prince,

while Shih-Min to whose genius and resolution the victory was due, was rewarded

with the title of Prince Chin. The disposition of the crown in favour of Chien-Cheng, who had done little to deserve it,

and the exclusion of Shih-Min, the real founder, from the succession contained

the seeds of trouble which was later to produce an evil fruit. For the time

this question was not acute. The Tang dynasty so far only ruled in less than two

provinces, Shansi and the Wei valley in Shensi. The rest of the empire remained

to be conquered.

By

the summer of a.d. 618 China was divided between twelve claimants: Li Yuan, and eleven others.

There was no reason to suppose that Li Yuan was likely to triumph over all his

fellows for, if none were mare formidable than the Tang emperor, some were at

least his equal in power and already ruled over a far wider extent of

territory. To the eight rebels who had been in the field against Yang Ti the

year three more, besides Li Yuan, had been added. In the south-east, along the

coast from the Yangtze to Fukien, the country had passed into the hands of a

certain Li Tzu-Tung.

Yu-Wen

Hua-Qu, the regicide, at first recognised a surviving

Sui prince as puppet emperor, but four months later murdered that shadow

monarch also, and usurped his title. His headquarters were Ta Ming Fu, in

Hopei.

Wang

Shih-Chung, the general despatched by Yang Ti to succour Lo Yang, at first acknowledged the Sui Prince Yueh

as legitimate emperor of the dynasty.

There ensued a desperate and confused struggle for the

mastery. No claimant was able to depend on the neutrality, still less the

friendship, of any other. An attack on one rival was certain to invite an

onslaught by some other at the least guarded point; if two rivals combined to

destroy a third, they immediately proceeded, the task achieved, to attack each other.

No mercy was shown to fallen leaders. Each “emperor” considered his rivals as

rebels, executed the captives, and exterminated their families. In this intricate

and desperate warfare, where security could only be attained by complete

victory, defeat meant death, and even surrender

purchased no safety, Shih-Min, almost alone, sustained the cause of the Tang.

Li Yuan from the moment of his enthronement resigned all military operations

to the direction of his younger son, occupying his days in Chang An with the civil

administration, from which he sought relief, at frequent intervals, in his favourite recreation of hunting.

Upon

Shih-Min, a youth of eighteen, devolved the double task of conquering the rival

“emperors” and parrying the raids of even mote formidable external foes—the

Turks. Sibir Khan had watched the collapse of the Sui

empire with complacency. Nothing but good, from the Turkish point of view,

could come from chaos and partition in the civilised empire within the Wall. The frontiers would be unguarded, opening a delightful

vista of opportunity for plundering forays. Weak Chinese pretenders, such as

Liang Shih-Tu and Liu Wu-Chou, would seek Turkish support, and as Turkish vassals

could be used to hamper any consolidation of a new Chinese power. Finally there

was always the chance that the weakness and disunion of the Chinese claimants would

open a way for a grand invasion, the conquest of all or part of China, and the foundation

of a Turkish dynasty.

The

Turkish menace hung, a black, portentous cloud in the northern sky. In all

Shih-Min’s campaigns this danger was always present, a constant source of weakness

and anxiety.

|

|