|

|

|

|

|

|||

A HISTORY OF BABYLON FROM THE FOUNDATION OF THE MONARCHY TO THE PERSIAN CONQUESTCHAPTER III

|

|||||

|

It will be noted that the new list of the kings of Larsa, important as

it undoubtedly is for the history of its own period, does not in itself supply

the long-desired link between the earlier and the later chronology of

Babylonia. The relationship of the First Dynasty of Babylon with that of Nisin

is, so far as the new list is concerned, left in the same state of uncertainty

as before. The possibility has long been foreseen that the Dynasty of Nisin and

the First Dynasty of Babylon overlapped each other, as was proved to have been

the case with the first dynasties in the Babylonian List of Kings, and as was

confidently assumed with regard to the dynasties of Larsa and Babylon. That no long

interval separated the two dynasties from one another had been inferred from

the character of the contract-tablets, dating from the period of the Nisin

Dynasty, which had been found at Nippur; for these were seen to bear a close

resemblance to those of the First Babylonian Dynasty in form, material,

writing, and terminology. There were obvious advantages to be obtained, if

grounds could be produced for believing that the two dynasties were not only

closely consecutive but were partly contemporaneous. For, in such a case, it

would follow that not only the earlier kings of Babylon, but also the kings of

Larsa, would have been reigning at the same time as the later kings of Nisin.

In fact, we should picture Babylonia as still divided into a number of smaller

principalities, each vying with the other in a contest for the hegemony and

maintaining a comparatively independent rule within its own borders. It was

fully recognized that such a condition of affairs would amply account for the

confusion in the later succession at Nisin, and our scanty knowledge of that

period could then be combined with the fuller sources of information on the

First Dynasty of Babylon.

In the absence of any definite synchronism, such as we already possessed

for deciding the interrelations of the early Babylonian dynasties, other means

were tried in order to establish a point of contact. The capture of Nisin by

Rim-Sin, which is recorded in date-formulae upon tablets found at Tell Sifr and

Nippur, was evidently looked upon as an event of considerable importance, since

it formed an epoch for dating tablets in that district. It was thus a

legitimate assumption that the capture of the city by Rim-Sin should be

regarded as having brought the Dynasty of Nisin to an end; such an assumption

certainly supplied an adequate reason for the rise of a new era in

time-reckoning. Now in the date-formulas of the First Dynasty of Babylon two

captures of the city of Nisin are commemorated, the earlier one in that for the

seventeenth year of Sin-muballit, the later in the formula for Hammurabi’s

seventh year. Advocates have been found for deriving each of these dates from

the capture of Nisin by Rim-Sin, and so obtaining the desired point of contact.

But the obvious objection to either of these views is that we should hardly

expect a victory by Rim-Sin to be commemorated in the date-formulae of his

chief rival; and certain attempts to show that Babylon was at the time the

vassal of Larsa have not proved very convincing. Moreover, if we accept the

earlier identification, it raises the fresh difficulty that the era of Nisin

was not disturbed by Hammurabi’s conquest of that city. The rejection of both

views thus leads to the same condition of uncertainty from which we started.

A fresh and sounder line of research has recently been opened up. A

detailed study has been undertaken of the proper names occurring on

contract-tablets from Nippur, and it was remarked that some of the proper names

found in documents belonging to the Nisin and Larsa Dynasties are identical

with those appearing on other Nippur tablets belonging to the First Dynasty of

Babylon. That they were borne by the same individuals is in many cases quite

certain from the fact that the names of their fathers are also given. Both sets

of documents were not only found at Nippur but were obviously written there,

since they closely resemble one another in general appearance, style and

arrangement. The same witnesses, too, occur again and again on them, and some

of the tablets, which were drawn up under different dynasties, are the work of

the same scribe. It has even been found possible, by the study of the proper

names, to follow the history of a family through three generations, during

which it was living at Nippur under different rulers belonging to the dynasties

of Nisin, Larsa and Babylon ; and one branch of the family can never have left

the city, since its members in successive generations held the office of “pashishu”,

or anointing-priest, in the temple of the goddess Ninlil.

Of such evidence it will suffice for the moment to cite two examples,

since they have a direct bearing on the assumption that Rim-Sin’s conquest of

Nisin put an end to the dynasty in that city. From two of the documents we

learn that Ziatum, the scribe, pursued his calling at Nippur not only under

Damik-ilishu, the last king of Nisin, but also under Rim-Sin of Larsa, a fact

which definitely proves that Nippur passed under the control of these two

rulers within the space of one generation. The other piece of evidence is still

more instructive. It has long been known that Hammurabi was Rim-Sin’s

contemporary, and from the new Kings’ List we have gained the further

information that he succeeded him upon the throne of Larsa. Now two other of

the Nippur documents prove that Ibkushu, the pashishu, or “anointing-priest” of the goddess Ninlil, was living

at Nippur under Damik-ilishu and also under Hammurabi in the latter’s

thirty-first year. This fact not only confirms our former inference, but gives

very good grounds for believing that the close of Damik-ilishu’s reign must

have fallen within that of Rim-Sin. We may therefore regard it as certain that

Rim-Sin’s conquest of Nisin, which began a new era for time reckoning in

central and southern Babylonia, put an end to the reign of Damik-ilishu and to

the Dynasty of Nisin, of which he was the last member. In order to connect the

chronology of Babylon with that of Nisin it therefore only remains to ascertain

at what period in Rim-Sin’s reign, as King of Larsa, his conquest of Nisin took

place.

It is at this point that a further discovery of Prof. Clay has furnished

us with the necessary data for a decision. Among the tablets of the Yale

Babylonian Collection he has come across several documents of Rim-Sin’s reign,

which bear a double-date. In every case the first half of the double-date

corresponds to the usual formula for the second year of the Nisin era. On two

of them the second half of the date-formula equates that year with the

eighteenth of some other era, while on two others the same year is equated with

the nineteenth year. It is obvious that we here have scribes dating documents

according to a new era, and explaining that that year corresponds to the

eighteenth (or nineteenth) of one with which they had been familiar, and which

the new method of time-reckoning was probably intended to displace. Now we know

that, before the capture of Nisin, the scribes in cities under Rim-Sin’s

control had been in the habit of dating documents by events in his reign,

according to the usual practice of early Babylonian kings. But this method was

given up after the capture of Nisin, and for at least thirty-one years after

that event the era of Nisin was in vogue. In the second year of the era, when

the new method of dating had just been settled, it would have been natural for

the scribes to add a note explaining the relationship of the new era to the

old. But, as the old changing formulas had been discontinued, the only possible

way to make the equation would have been to reckon the number of years Rim-Sin

had been upon the throne. Hence we may confidently conclude that the second

figure in the double-dates was intended to give the year of Rim-Sin’s reign

which corresponded to the second year of the Nisin era.

It may seem strange that in some of the documents with the double-dates

the second figure is given as eighteen and in others as nineteen. There is more

than one way in which it is possible to explain the discrepancy. If we assume

that the conquest of Nisin took place towards the close of Rim-Sin’s seventeenth

year, it is possible that, during the two years that followed, alternative

methods of reckoning were in vogue, some scribes regarding the close of the

seventeenth year as the first year of the new epoch, others beginning the new

method of time-reckoning with the first day of the following Nisan. But that

explanation can hardly be regarded as probable, for, in view of the importance

attached to the conquest, the promulgation of the new era commemorating the

event would have been carried out with more than ordinary ceremonial, and the

date of its adoption would not have been left to the calculation of individual

scribes. It is far more likely that the explanation is to be sought in the

second figure of the equation, the discrepancy being due to alternative methods

of reckoning Rim-Sin’s regnal years. Again assuming that the conquest took

place in Rim-Sin’s seventeenth year, those scribes who counted the years from

his first date-formula would have made the second year of the era the

eighteenth of his reign. But others may have included in their total the year

of Rim-Sin’s accession to the throne, and that would account for their

regarding the same year as the nineteenth according to the abolished system of

reckoning. This seems the preferable explanation of the two, but it will be

noticed that, on either alternative, we must regard the first year of the Nisin

era as corresponding to the seventeenth year of Rim-Sin’s reign.

One other point requires to be settled, and that is the relation of the

Nisin era to the actual conquest of the city. Was the era inaugurated in the

same year as the conquest, or did its first year begin with the following first

of Nisan? In the course of the fifth chapter the early Babylonian method of

time-reckoning is referred to, and it will be seen that precisely the same

question arises with regard to certain other events commemorated in

date-formulas of the period. Though some features of the system are still

rather uncertain, we have proof that the greater historical events did in certain

cases affect the current date-formula, especially when this was of a

provisional character, with the result that the event was commemorated in the

final formula for the year of its actual occurrence. Arguing from analogy, we

may therefore regard the inauguration of the Nisin era as coinciding with the

year of the city’s capture. In the case of this particular event the arguments

in favour of such a view apply with redoubled force, for no other victory by a

king of Larsa was comparable to it in importance. We may thus regard the last

year of Damik-ilishu, King of Nisin, as corresponding to the seventeenth year

of Rim-Sin, King of Larsa. And since the relationship of Rim-Sin with

Hammurabi has been established by the new list of Larsa kings, we are at length

furnished with the missing synchronism for connecting the dynasties of the

Nippur Kings’ List with those of Babylon.

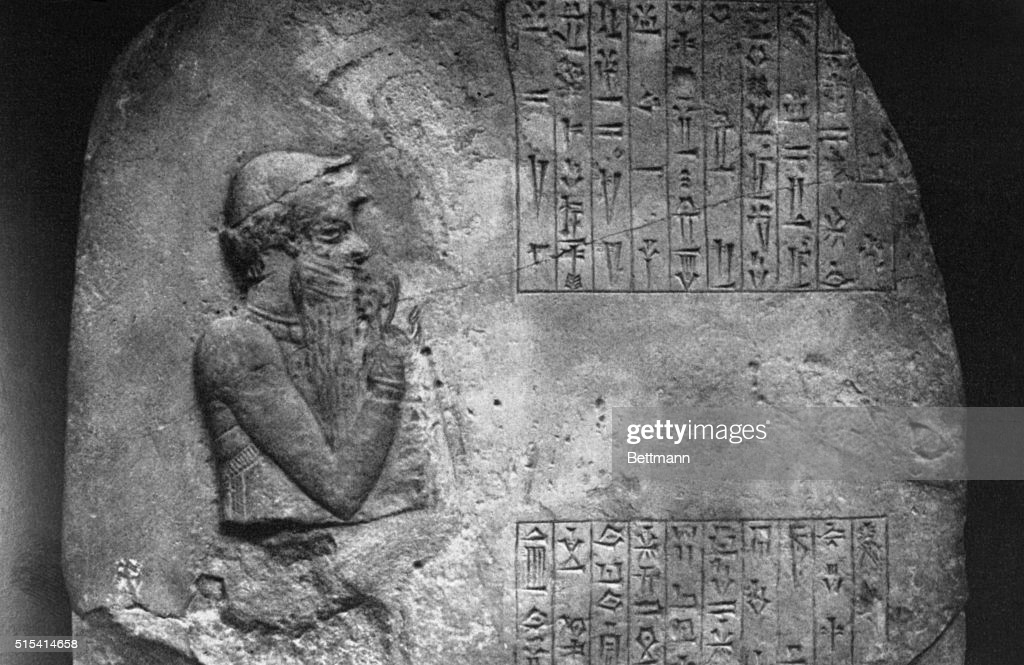

HAMMURABI, KING OF BABYLON, FROM A RELIEF IN THE

BRITISH

MUSEUM.

|

We may now return to the difficulty introduced by the new list of Larsa

kings, on which, as we have already noted, the long reign of Rim-Sin is

apparently entered as preceding the thirty-second year of Hammurabi’s rule in

Babylon. Soon after the publication of the chronicle, from a broken passage on

which it was inferred that Rim-Sin survived into Samsu-iluna’s reign, an

attempt was made to explain the words as referring to a son of Rim-Sin and not

to that ruler himself. But it was pointed out that the sign, which it was

suggested should be rendered as “son”, was never employed with that meaning in

chronicles of the period, and that we must consequently continue to regard the

passage as referring to Rim-Sin. It was further noted that two contract-tablets

found at Tell Sifr, which record the same deed of sale, are dated the one by Rim-Sin,

and the other in Samsu-iluna’s tenth year. In both of these deeds the same

parties are represented as carrying out the same transaction, and, although

there is a difference in the price agreed upon, the same list of witnesses

occur on both, and both are dated in the same month. The most reasonable

explanation of the existence of the two documents would seem to be that, at the

period the transaction they record took place, the possession of the town now

marked by the mounds of Tell Sifr was disputed by Rim-Sin and Samsu-iluna. Soon

after the first of the deeds had been drawn up, the town may have changed

hands, and, in order that the transaction should still be recognized as valid,

a fresh copy of the deed was made out with the new ruler’s date-formula

substituted for that which was no longer current. But whatever explanation be

adopted, the alternative dates upon the documents, taken in conjunction with

the chronicle, certainly imply that Rim-Sin was living at least as late as

Samsu-iluna’s ninth year, and probably in the tenth year of his reign.

If, then, we accept the face value of the figures given by the new Larsa

Kings’ List, we are met by the difficulty already referred to, that Rim-Sin

would have been an active political force in Babylonia some eighty-three years

after his own accession to the throne. And assuming that he was merely a boy of

fifteen when he succeeded his brother at Larsa, he would have been taking the

field against Samsu-iluna in his ninety-eighth year. But it is extremely

unlikely that he was so young at his accession, and, in view of the

improbabilities involved, it is preferable to scrutinize the figures in the

Larsa list with a view to ascertaining whether they are not capable of any

other interpretation.

It has already been noted that the Larsa List is a contemporaneous

document, since the scribe has added the title of “king” to the last name only,

that of Samsu-iluna, implying that he was the reigning king at the time the

document was drawn up. It is unlikely, therefore, that any mistake should have

been made in the number of years assigned to separate rulers, the date-formulas

and records of whose reigns would have been easily accessible for consultation

by the compiler. The long reign of sixty-one years, with which Rim-Sin is

credited, must be accepted as correct, for it does not come to us as a

tradition incorporated in a Neo-Babylonian document, but is attested by a

scribe 'writing within two years of the time when, as we have seen, Rim-Sin was

not only living but fighting against the armies of Babylon. In fact, the

survival of Rim-Sin throughout the period of Hammurabi’s rule at Larsa, and

during the first ten years of Samsu-iluna’s reign, perhaps furnishes us with

the solution of our problem.

If Rim-Sin had not been deposed by Hammurabi on his conquest of Larsa,

but had been retained there with curtailed powers as the vassal of Babylon, may

not his sixty-one years of rule have included this period of dependence? In

that case he may have ruled as independent King of Larsa for thirty-nine years,

followed by twenty-two years during which he owed allegiance successively to

Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna, until in the latter’s tenth year he revolted and

once more took the field against Babylon. It is true that, with the missing

figures in the Kings’ List restored as suggested by Professor Clay, the figure

for the total duration of the dynasty may be cited against this explanation;

for the two hundred and eighty-nine years is obtained by regarding the whole of

Rim-Sin’s reign as anterior to Hammurabi’s conquest. There are two

possibilities with regard to the figure. In the first place it is perhaps just

possible that Sin-idinnam and Sin-ikisham may have reigned between them

thirty-five years, in place of the thirteen years provisionally assigned to

them. If that were so, the scribe’s total would be twenty-two years less than

the addition of his figures, and the discrepancy could only be explained by

some such overlapping as suggested. But it is far more likely that the figures

are correctly restored, and that the scribe’s total corresponds to that of the

figures in the list. On such an assumption it is not improbable that he

mechanically added up the figures placed opposite the royal names, without

deducting from his total the years of Rim-Sin’s dependent rule.

This explanation appears to be the one least open to objection, as it

does not necessitate the alteration of essential figures, and merely postulates

a natural oversight on the part of the compiler. The placing of Hammurabi and

Samsu-iluna in the list after, and not beside, Rim-Sin would be precisely on

the lines of the Babylonian Kings’ List, in which the Second Dynasty is

enumerated between the First and Third, although, as we now know, it overlapped

a part of each. In that case, too, the scribe has added up the totals of his

separate dynasties, without any indication of their periods of overlapping. The

explanation in both cases is, of course, that the modern system of arranging

contemporaneous rulers in parallel columns had not been evolved by the

Babylonian scribes. Moreover, we have evidence that at least one other compiler

of a dynastic list was careless in adding up his totals; from one of his

discrepancies it would seem that he counted a period of three months as three

years, while in another of his dynasties a similar period of three months was

probably counted twice over both as months and years. It is true that the

dynastic list in question is a late and not a contemporaneous document, but at

least it inclines us to accept the possibility of such an oversight as that

suggested on the part of the compiler of the Larsa list.

The only reason which we have as yet examined for equating the first

twenty-two years of Babylon’s suzerainty over Larsa with the latter part of

Rim-Sin’s reign has been the necessity of reducing the duration of that

monarch’s life within the bounds of probability. If this had been the only

ground for the assumption, it might perhaps have been regarded as more or less

problematical. But the Nippur contract-tablets and legal documents, to which

reference has already been made, furnish us with a number of separate and

independent pieces of evidence in its support. The tablets contain references

to officials and private people who were living at Nippur in the reigns of

Damik-ilishu, the last king of Nisin, and of Rim-Sin of Larsa, and also under

Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna of Babylon. Most of the tablets of Rim-Sin’s period

are dated by the Nisin era, and, since the dates of those drawn up in the

reigns of Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna can be definitely ascertained by means of

their date-formulas, it is possible to estimate the intervals of time

separating references to the same man or to a man and his son. It is remarkable

that in some cases the interval of time appears excessive if the whole of

Rim-Sin’s reign of sixty-one years be placed before Hammurabi’s capture of

Larsa. If, on the other hand, we regard Rim-Sin as Babylon’s vassal for the

last twenty-two years of his rule in Larsa, the intervals of time are reduced

to normal proportions. As the point is of some importance for the chronology,

it may be as well to cite one or two examples of this class of evidence, in

order that the reader may judge of its value for himself.

The first example we will examine will be that furnished by Ibkushu, the

anointing-priest of Ninlil, to whom we have already referred as having lived at

Nippur under Damik-ilishu and also under Hammurabi in the latter’s thirty-first

year2; both references, it may be noted, describe him as holding his priestly

office^ at Nippur. Now, if we accept the face value of the figures in the Larsa

List we obtain an interval between these two references of at least forty-four

years and probably more. By the suggested interpretation of the figures in the

List the interval would be reduced by twenty-two years. A very similar case is

that of the scribe Ur-kingala, who is mentioned in a document dated in the

eleventh year of the Nisin era, and again in one of Samsu-iluna’s fourth year.

In the one case we obtain an interval of fifty years between the two

references, while in the other it is reduced to twenty-eight years. Very

similar results follow if we examine references on the tablets to fathers and

their sons. A certain Adad-rabi, for example, was living at Nippur under

Damik-ilishu, while his two sons Mar-irsitim and Mutum-ilu are mentioned there

in the eleventh year of Samsu-iluna’s reign. In the one case we must infer an

interval of at least sixty-seven years, and probably more, between father and

sons; in the other an interval of forty-five years or more is obtained. It will

be unnecessary to examine further examples, as those already cited may suffice

to illustrate the point. It will be noted that the unabridged interval can in no

single instance be pronounced impossible. But the cumulative effect produced is

striking. The independent testimony of these private documents and contracts

thus converges to the same point as the data with regard to the length of

Rim-Sin’s life. Several of the figures so obtained suggest that, taken at their

face value, the regnal years in the Larsa List yield a total that is about one

generation too long. They are thus strongly in favour of the suggested method

of interpreting Rim-Sin’s reign in the Larsa succession.

We may thus provisionally place the sixty-first year of Rim-Sin’s rule

at Larsa in the tenth year of Samsu-iluna’s reign, when we may assume that he

revolted and took the field against his suzerain. It was in that year that Tell

Sifr changed hands for a time. But it is probably a significant fact that not a

single document of Samsu-iluna’s reign has been found in that district dated

after his twelfth year. In fact we shall see reason to believe that the whole

of Southern Babylonia soon passed from the control of Babylon, though

Samsu-iluna succeeded in retaining his hold on Nippur for some years longer.

Meanwhile it will suffice to note that the suggested sequence of events fits in

very well with other references in the date-lists. The two defeats of Nisin by

Hammurabi and his father Sin-muballit, which have formed for so long a subject

of controversy, now cease to be a stumbling-block. We see that both took place

before Rim-Sin’s capture of Nisin, and were merely temporary successes which had

no effect upon the continuance of the Nisin dynasty. That was brought to an end

by Rim-Sin’s victory in his seventeenth year, when the Nisin era of dating was

instituted. That, in cities where it had been long employed, the continued use

of the era alongside his own formulas should have been permitted by Hammurabi

for some eight years after his capture of Larsa, is sufficiently explained by

our assumption that Rim-Sin was not deposed, but was retained in his own

capital as the vassal of Babylon. There would have been a natural reluctance to

abandon an established era, especially if Babylon’s authority was not rigidly

enforced during the first few years of her suzerainty, as with earlier vassal

states.

The overlapping of the Dynasty of Nisin with that of Babylon for a

period of one hundred and eleven years, which follows from the new information

afforded by the Yale tablets, merely carries the process still further that was

noted some years ago with regard to the first three Dynasties of the Babylonian

List of Kings. At the time of the earlier discovery considerable difference of

opinion existed as to the number of years, if any, during which the Second

Dynasty of the List held independent sway in Babylonia. The archaeological

evidence at that time available seemed to suggest that the kings of the

Sea-Country never ruled in Babylonia, and that the Third, or Kassite, Dynasty followed

the First Dynasty without any considerable break. Other writers, in their

endeavours to use and reconcile the chronological references to earlier rulers

which occur in later texts, assumed a period of independence for the Second

Dynasty which varied, according to their differing hypotheses, from one hundred

and sixty-eight to eighty years. Since the period of the First Dynasty was not

fixed independently, the complete absence of contemporary evidence with regard

to the Second Dynasty led to a considerable divergence of opinion upon the

point.

So far as the archaeological evidence is concerned, we are still without

any great body of documents dated in their reigns, which should definitely

prove the rule of the Sea-Country kings in Babylonia. But two tablets have now

been discovered in the Nippur Collections which are dated in the second year of

Iluma-ilum, the founder of the Second Dynasty. And this fact is important,

since it proves that for two years at any rate he exercised control over a

great part of Babylonia. Now among the numerous documents dated in the reigns

of Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna, which have been found at Nippur, none are later

than Samsu-iluna’s twenty-ninth year, although the succession of dated

documents up to that time is almost unbroken. It would thus appear that after

Samsu-iluna’s twenty-ninth year Babylon lost her hold upon Nippur. It is

difficult to resist the conclusion that the power which drove her northwards

was the kingdom of the Sea-Country, whose founder Iluma-ilum waged successful

campaigns against both Samsu-iluna and his son Abi-eshu, as we learn from the

late Babylonian chronicle. Another fact that is probably of equal significance

is that, of the tablets from Larsa and its neighbourhood, none have been found

dated after Samsu-iluna’s twelfth year, although we have numerous examples

drawn up during the earlier years of his reign. We may therefore assume that

soon after his twelve years of rule at Larsa, which are assigned to him on the

new Kings’ List, that city was lost to Babylon. And again it is difficult to

resist the conclusion that the Sea-Country was the aggressor. From

Samsu-iluna’s own date-formulas we know that in his twelfth year “all the lands

revolted ” against him. We may therefore with considerable probability place

Iluma-ilum’s revolt in that year, followed immediately by his establishment of

an independent kingdom in the south. He probably soon gained control over Larsa

and gradually pushed northwards until he occupied Nippur in Samsu-iluna’s

twenty-ninth or thirtieth year.

BRICK Of WARAD-SIN, KING OF LARSA, RECORDING BUILDING-OPERATIONS

IN THE CITY OF UR.

|

Such appears to be the most probable course of events, so far as it may

be determined in accordance with our new evidence. And since it definitely

proves that the founder of the Second Dynasty of the Kings’ List established,

at any rate for a time, an effective control over southern and central

Babylonia, we are the more inclined to credit the kings of the Sea-Country

’with having later on extended their authority farther to the north. The fact

that the compiler of the Babylonian List of Kings should have included the

rulers of the Sea-Country in that document has always formed a weighty argument

for regarding some of them as having ruled in Babylonia; and it was only

possible to eliminate the dynasty entirely from the chronological scheme by a

very drastic reduction of his figures for some of their reigns. The founder of

the dynasty, for example, is credited with a reign of sixty years, two other

rulers with reigns of fifty-five years, and a fourth with fifty years. But the

average duration of the reigns in the dynasty is only six years in excess of

that for the First Dynasty, which also consisted of eleven kings. And, in view

of the sixty-one years credited to Rim-Sin in the newly recovered Larsa List,

which is a contemporaneous document and not a later compilation, we may regard

the traditional length of the dynasty as perhaps approximately correct.

Moreover, in all other parts of the Kings’ List that can be controlled by

contemporaneous documents, the general accuracy of the figures has been amply

vindicated. The balance of evidence appears, therefore, to be in favour of

regarding the compiler’s estimate for the duration of his Second Dynasty as

also resting on reliable tradition.

In working out the chronological scheme it only remains therefore to fix

accurately the period of the First Dynasty, in order to arrive at a detailed

chronology for both the earlier and the later periods. Hitherto, in default of

any other method, it has been necessary to rely on the traditions which have

come down to us from the history of Berossus or on chronological references to

early rulers which occur in the later historical texts. A new method of

arriving at the date of the First Dynasty, in complete independence of such

sources of information, was hit upon three years ago by Dr. Kugler, the Dutch astronomer,

in the course of his work on published texts that had any bearing on the

history and achievements of Babylonian astronomy. Two such tablets had been

found by Sir Henry Layard at Nineveh and were preserved in the Kouyunjik

Collection of the British Museum. Of these one had long been published and its

contents correctly classified as a series of astronomical omens derived from

observations of the planet Venus. It was certain that this Assyrian text was a

copy of an earlier Babylonian one, since that was definitely stated in its

colophon. The second of the two inscriptions proved to be in part a duplicate,

and by using them in combination Dr. Kugler was able to restore the original

text with a considerable degree of certainty. But a more important discovery

was that he succeeded in identifying precisely the period at which the text was

originally drawn up, and the astronomical observations recorded. For he noted

that in the eighth section of his restored text there was a chronological note,

dating that section by the old Babylonian date-formula for the eighth year of

Ammi-zaduga, the tenth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty. As his text

contained twenty-one sections, he drew the legitimate inference that it gave

him a series of observations of the planet Venus for each of the twenty-one

years of Ammi-zaduga’s reign.

The observations from which the omens were derived consist of dates for

the heliacal rising and setting of the planet Venus. The date was observed at

which the planet was first visible in the east, the date of her disappearance

was noted, and the duration of her period of invisibility; similar dates were

then observed of her first appearance in the west as the Evening Star, followed

as before by the dates of her disappearance and her period of invisibility. The

taking of such observations does not, of course, imply any elaborate

astronomical knowledge on the part of the early Babylonians. This beautiful

planet must have been the first, after the moon, to attract systematic

observation, and thanks to her nearly circular orbit, no water-clock nor

instrument for measuring angles was required. The astrologers of the period

would naturally watch for the planet’s first appearance in the glimmer of the

dawn, that they might read therefrom the will of the great goddess with whom

she was identified. They would note her gradual ascension, decline and

disappearance, and then count the days of her absence until she reappeared at

sunset and repeated her movements of ascension and decline. Such dates, with

the resulting fortunes of the country, form the observations noted in the text

that was drawn up in Ammi-zaduga’s reign.

It will be obvious that the periodic return of the same appearance of

the planet Venus would not in itself have supplied us with sufficient means for

determining the period of the observations. But we obtain additional data if we

employ our information with the further object of ascertaining the relative

positions of the sun and moon. On the one hand the heliacal risings and

settings of Venus are naturally bound up in a fixed relationship of Venus to

the sun ; on the other hand the series of dates by the days of the month

furnishes us with the relative position of the moon -with regard to the sun on

the days cited. Without the second criterion, the first would be of very little

use. But, taken together, the combination of the sun, Venus and the moon are of

the greatest value for fixing the position of the group of years, covered by

the observations, within any given period of a hundred years or more. Now if we

eliminate the Second Dynasty altogether from the Babylonian Kings’ List, it is

certain that Ammi-zaduga’s reign could not have fallen much later than 1800 B.C.;

on the other hand, in view of the ascertained minimum of overlapping of the

First Dynasty by the Second, it is equally certain that it could not have

fallen earlier than 2060 B.C. The period of his reign must thus be sought

within the interval between these dates. But, in order to be on the safe side,

Dr. Kugler extended both the limits of the period to be examined ; he conducted

his researches within the period from 2080 to 1740 B.C. He began by taking two

observations for the sixth year of Ammi-zaduga, which gave the dates for the

heliacal setting of Venus in the west and her rising in the east, and, by using

the days of the month to ascertain the relative positions of the moon, he found

that throughout the whole course of his period this particular combination took

place three times. He then proceeded to examine in the same way the rest of the

observations, with their dates, as supplied by the two tablets, and, by working

them out in detail for the central one of his three possible periods, he

obtained confirmation of his view that the observations did cover a consecutive

period of twenty-one years. In order to obtain independent proof of the

correctness of his figures, he proceeded to examine the dates upon contemporary

legal documents, which could be brought into direct or indirect relation to the

time of harvest. These dates, according to his interpretation of the calendar,

offered a means of controlling his results, since he was able to show that a

higher or lower estimate tended to throw out the time of harvest from the month

of Nisan, which was peculiarly the harvest month.

It must be admitted that the last part of the demonstration stands in a

different category to the first; it does not share the simplicity of the

astronomical problem. It formed, indeed, merely an additional method of testing

the interpretation of the astronomical evidence, and the dates resulting from

the latter were obtained in complete independence of the farming-out contracts

of the period. Taking, then, the three alternative dates, there can be no

doubt, if we accept the figure of the Kings’ List for the Second Dynasty as

approximately accurate, that the central of the three periods is the only one possible

for Ammi-zaduga’s reign; for either of the other two would imply too high or

too low a date for the Third Dynasty of the Kings’ List. We may thus accept the

date of 1977 B.C. as that of Ammi-zaduga’s accession, and we thereby obtain a

fixed point for working out the chronology of the First Dynasty of Babylon,

and, consequently, of the partly contemporaneous Dynasties of Larsa and of

Nisin, and of the still earlier Dynasty of Ur. Incidentally it assists in

fixing within comparatively narrow limits the period of the Kassite conquest

and of the following dynasties of Babylon. Starting from this figure as a

basis, and making use of the information already discussed, it would follow

that the Dynasty of Nisin was founded in the year 2339 B.C., that of Larsa only

four years later in 2335 B.C., and the First Dynasty of Babylon after a further

interval of a hundred and ten years in 2225 B.C.

It will have been seen that the suggested system of chronology has been

settled in complete independence of the chronological notices to earlier rulers

which have come down to us in the inscriptions of some of the later Assyrian

and Babylonian kings. Hitherto these have furnished the principal starting

points, on which reliance has been placed to date the earlier periods in the

history of Babylon. In the present case it will be pertinent to examine them

afresh and ascertain how far they harmonize with a scheme which has been evolved

without their help. If they are found to accord very well with the new system,

we may legitimately see in such an agreement additional grounds for believing

we are on the right track. Without pinning one’s faith too slavishly to any

calculation by a native Babylonian scribe, the possibility of harmonizing such

references at least removes a number of difficulties, which it has always been

necessary either to ignore or to explain away.

Perhaps the chronological notice which has given rise to most discussion

is the one in which Nabonidus refers to the period of Hammurabi’s reign. On one

of his foundation-cylinders Nabonidus states that Hammurabi rebuilt E-babbar,

the temple of the Sun-god in Larsa, seven hundred years before Burna-Buriash. At

a time when it was not realized that the First and Second Dynasties of the

Kings’ List were partly contemporaneous, the majority of writers were content

to ignore the apparent inconsistency between the figures of the Kings’ List and

this statement of Nabonidus. Others attempted to get over the difficulty by

emending the figures in the List and by other ingenious suggestions; for it was

felt that to leave a discrepancy of this sort without explanation pointed to a

possibility of error in any scheme necessitating such a course. We will see,

then, how far the estimate of Nabonidus accords with the date assigned to

Hammurabi under our scheme. From the Tell el-Amarna letters we know that

Burna-Buriash was the contemporary of Amenhetep IV., to whose accession most

historians of Egypt now agree to assign a date in the early part of the

fourteenth century B.C. We may take 1380 B.C. as representing approximately the

date which, according to the majority of the schemes of Egyptian chronology,

may be assigned to Amenhetep IV’s accession. And by adding seven hundred years

to this date we obtain, according to the testimony of Nabonidus, a date for

Hammurabi of about 2080 B.C. According to our scheme the last year of

Hammurabi’s reign fell in 2081 B.C., and, since the seven hundred years of

Nabonidus is obviously a round number, its general agreement with the scheme is

remarkably close.

The chronological notice of Nabonidus thus serves to confirm, so far as

its evidence goes, the general accuracy of the date assigned to the First Dynasty.

In the case of the Second Dynasty we obtain an equally striking confirmation,

when we examine the only available reference to the period of one of its kings

which is found in the record of a later ruler. The passage in question occurs

upon a boundary-stone preserved in the University Museum of Pennsylvania,

referring to events which took place in the fourth year of Enlil-nadin-apli. In

the text engraved upon the stone it is stated that 696 years separated

Gulkishar (the sixth king of the Second Dynasty) from Nebuchadnezzar, who is of

course to be identified with Nebuchadnezzar I, the immediate predecessor of

Enlil-nadin-apli upon the throne of Babylon. Now we know from the

“Synchronistic History” that Nebuchadnezzar I was the contemporary of

Ashur-resh-ishi, the father of Tiglath-pileser I, and if we can establish

independently the date of the latter’s accession, we obtain approximate dates

for Nebuchadnezzar and consequently for Gulkishar.

In his inscription on the rock at Bavian Sennacherib tells us that 418

years elapsed between the defeat of Tiglath-pileser I by Marduk-nadin-akhe and

his own conquest of Babylon in 689 B.C. Tiglath-pileser was therefore reigning

in 1107 B.C., and we know from his Cylinder-inscription that this year was not

among the first five of his reign; on this evidence the beginning of his reign

has been assigned approximately to 1120 B.C. Nebuchadnezzar I, the contemporary

of Tiglath-pileser’s father, may thus have come to the throne at about 1140 B.C.;

and, by adding the 696 years to this date, we obtain an approximate date of

1836 B.C. as falling within the reign of Gulkishar of the Second Dynasty. This

date supports the figures of the Kings’ List, according to which Gulkishar

would have been reigning from about 1876 to 1822 B.C. But it should be noted

that the period of 696 years upon the boundary-stone, though it has an

appearance of great accuracy, was probably derived from a round number; for the

stone refers to events which took place in Enlil-nadin-apli’s fourth year, and

the number 696 may have been based upon the estimate that seven hundred years

separated Enlil-nadin-apli’s reign from that of Gulkishar. It is thus probable

that the reference should not be regarded as more than a rough indication of

the belief that a portion of Gulkishar’s reign fell within the second half of

the nineteenth century. But, even on this lower estimate of the figure’s

accuracy, its agreement with our scheme is equally striking.

One other chronological reference remains to be examined, and that is

the record of Ashur-bani-pal, who, when describing his capture of Susa in about

647 B.C., relates that he recovered the image of the goddess Nana, which the

Elamite Kudur-Nankhundi had carried off from Erech sixteen hundred and

thirty-five years before. This figure would assign to Kudur-Nankhundi’s

invasion an approximate date of 2282 B.C. As we possess no other reference to, nor

record of, an early Elamite king of this name, there is no question of

harmonizing this figure with other chronological records bearing on his reign.

All that we can do is to ascertain whether, according to our chronological

scheme, the date 2282 B.C. falls within a period during which an Elamite king

would have been likely to invade Southern Babylonia and raid the city of Erech.

Tested in this way, Ashurbanipal’s figure harmonizes well enough with the

chronology, for Kudur-Nankhundi would have invaded Babylonia fifty-seven years

after a very similar Elamite invasion which brought the Dynasty of Ur to an

end, and gave Nisin her opportunity of securing the hegemony. That Elam

continued to be a menace to Babylonia is sufficiently proved by Kudur-Mabuk’s

invasion, which resulted in placing his son Warad-Sin upon the throne of Larsa

in 2143 B.C. It will be noted that

Ashurbanipal’s figure places Kudur-Nankhundi’s raid on Erech in the period

between the two most notable Elamite invasions of early Babylonia, of which we

have independent evidence.

Another advantage of the suggested chronological scheme is that it

enables us to clear up some of the problems presented by the dynasties of

Berossus, at least so far as concerns the historical period in his system of

chronology. In a later historian of Babylon we should naturally expect to find

that period beginning with the first dynasty of rulers in the capital; but

hitherto the available evidence did not seem to suggest a date that could be

reconciled with his system. It may be worth while to point out that the date

assigned under the new scheme for the rise of the First Dynasty of Babylon coincides

approximately with that deduced for the beginning of the historical period in

Berossus. Five of the historical dynasties of Berossus, following his first

dynasty of eighty-six kings who ruled for 34,090 years after the Deluge, are

preserved only in the Armenian version of the Chronicles of Eusebius and are

the following:—

Dynasty II., 8 Median usurpers, ruling 224 years ;

Dynasty III., 11 kings, the length of their rule wanting;

Dynasty IV., 49 Chaldean kings, ruling 458 years;

Dynasty V., 9 Arab kings, ruling for 245 years ;

Dynasty VI., 45 kings, ruling for 526 years.

It is not quite clear to what stage in the national history Berossus

intended his sixth dynasty to extend ; and in any case, the fact that the

figure is wanting for the length of his third dynasty, renders their total

duration a matter of uncertainty. But, in spite of these drawbacks, a general

agreement has been reached as to a date for the beginning of his historical

period, based on considerations independent of the figures in detail. A. von

Gutschmid’s suggestion that the kings after the Deluge were grouped by Berossus

in a cycle of ten sars, i.e. 36,000 years, furnished the key

that has been used for solving the problem. For, if the first dynasty be

subtracted from this total, the remaining number of years would give the total

length of the historical dynasties. Thus, if we take the length of the first

dynasty as 34,090 years, the duration of the historical dynasties is seen to

have been 1910 years. Now the statement attributed to Abydenus by Eusebius, to

the effect that the Chaldeans reckoned their kings from Alorus to Alexander, has

led to the suggestion that the period of 1910 years was intended to include the

reign of Alexander the Great (331-323 B.C.). If therefore we add 1910 years to

322 B.C., we obtain 2232 B.C. as the beginning of the historical period with

which the second dynasty of Berossus opened. It may be added that the same

result has been arrived at by taking 34,080 years as the length of his first

dynasty, and by extending the historical period of 1920 years down to 312 B.C.,

the beginning of the Seleucid Era.

Incidentally it may be noted that this date has been harmonized with the

figure assigned in the margin of some manuscripts as representing the length of

the third dynasty of Berossus. It has usually been held that his sixth dynasty

ended with the predecessor of Nabonassar upon the throne of Babylon, and that

the following or seventh dynasty would have begun in 747 B.C. But it has been pointed out that, after enumerating

the dynasties II.-VI., Eusebius goes on to say that after these rulers came a

king of the Chaldeans whose name was Phulus; and this phrase has been explained

as indicating that the sixth dynasty of Berossus ended at the same point as the

Ninth Babylonian Dynasty, in 732 B.C., that is to say, with the reign of

Nabu-shum-ukin, the contemporary of Tiglath-pileser IV, whose original name of

Pulu is preserved in the Babylonian List of Kings. Thus the seventh dynasty of

Berossus would have begun with the reign of the usurper Ukin-zer, who was also

the contemporary of Tiglath-pileser. On this supposition the figure “forty-eight”,

which occurs in the margin of certain manuscripts of the Armenian version of

Eusebius, may be retained for the number of years assigned by Berossus to his

third dynasty. A further confirmation of the date 2232 B.C. for the beginning

of the historical period of Berossus has been found in a statement derived from

Porphyrius, to the effect that, according to Callisthenes, the Babylonian

records of astronomical observations extended over a period of 1903 years down

to the time of Alexander of Macedon. Assuming that the reading 1903 is correct,

the observations would have extended back to 2233 B.C., a date differing by

only one year from that obtained for the beginning of Berossus’ historical

dynasties.

Thus there are ample grounds for regarding the date 2232 B.C. as

representing the beginning of the historical period in the chronological system

of Berossus; and we have already noted that in a late Babylonian historian,

writing during the Hellenistic period, we should expect the beginning of his

history, in the stricter sense of the term, to coincide with the first recorded

dynasty of Babylon, as distinct from rulers of other and earlier city-states.

It will be observed that this date is only seven years out with that obtained

astronomically by Dr. Kugler for the rise of the First Dynasty of Babylon. Now

the astronomical demonstration relates only to the reign of Ammi-zaduga, who

was the tenth king of the First Dynasty ; and to obtain the date 2225 B.C. for

Sumu-abum’s accession, reliance is naturally placed on figures for the

intermediate reigns which are supplied by the contemporaneous date-lists. But

the Babylonian Kings’ List gives figures which were current in the

Neo-Babylonian period; and, by employing it in place of contemporaneous

records, we obtain the date 2229 B.C. for Sumu-abum’s accession, which presents

a discrepancy of only three years to that deduced from Berossus. In view of the

slight inconsistencies with the Kings’ List which we find in at least one of

the late chronicles, it is clear that the native historians, who compiled their

records during the later periods, found a number of small variations in the

chronological material on which they had to rely. While there was probably

agreement on the general lines of the later chronology, the traditional length

of some reigns and dynasties might vary in different documents by a few years.

We may conclude therefore that the evidence of Berossus, so far as it can be

reconstituted from the summaries preserved in other works, may be harmonized

with the date obtained independently for the First Dynasty of Babylon.

The new information, which has been discussed in this chapter, has enabled

us to carry further than was previously possible the process of reconstructing

the chronology; and we have at last been able to connect the earlier epochs in

the country’s history with those which followed the rise of Babylon to power.

On the one hand we have obtained definite proof of the overlapping of further

dynasties with that of the West Semitic kings of Babylon. On the other hand,

the consequent reduction in date is more than compensated by new evidence

pointing to the probability of a period of independent rule in Babylonia on the

part of some of the Sea-Country kings. The general effect of the new

discoveries is thus of no revolutionary character. It has resulted, rather, in

local rearrangements, which to a considerable extent are found to counterbalance

one another in their relation to the chronological scheme as a whole. Perhaps

the most valuable result of the regrouping is that we are furnished with the

material for a more detailed picture of the gradual rise of Babylon to power.

We shall see that the coming of the Western Semites effected other cities than

Babylon, and that the triumph of the invaders marked only the closing stage of

a long and varied struggle.