|

|

|

CHAPTER XVIII.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

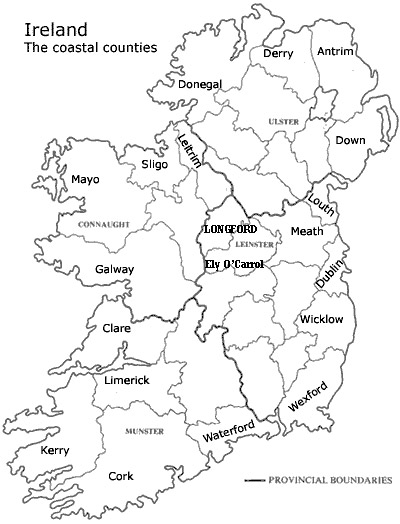

In the years immediately

following on the plantation of Ulster three other plantations, in North Wexford

(1610-20), Longford and Ely O’Carroll (1615-20), Leitrim and the midland districts along the Shannon (1620),

comprising nearly half a million acres of land, were taken in hand. But, though

not one of these could be regarded as even moderately successful, and though

the market price of land in Ulster averaged not more than £50 for a thousand

acres, such were still the fortunes to be made in land-jobbing that it seemed

as if the natural boundaries of Ireland could alone set a limit to the craving

for Irish land. It was indeed an age of planters and plantation projects; and

the philosophical reasoning of Bacon was hardly required to convince men

willing to risk their lives and fortunes in trying to effect a settlement in

Virginia or on the inhospitable coasts of Newfoundland that they would find a

more remunerative sphere for their labors nearer home, and would at the same

time render the State signal service by spreading order and civility among the

Irish. For Ireland it was unfortunate that the former consideration largely

outweighed the latter. The whole aspect of affairs had changed entirely since

the days when Henry VIII had proposed to win Ireland by “sober ways, political drifts,

and amiable persuasions”. For this alteration the Irish had themselves been

largely to blame. Their inability or unwillingness to accommodate themselves to

English ideas, their repeated rebellions and intrigues with foreign Powers, had

exhausted the patience of English statesmen and forced them, at first more in

self-defence than from any other reason, to adopt a policy of extirpation and

plantation.

But, with whatever feeling of satisfaction the plantation policy might be regarded in England as offering a hopeful solution of the Irish problem, in Ireland it provoked widespread indignation, not merely on the part of those on whose ruin it was based, but amongst those whose loyalty to the English Crown had never been called seriously in question. To the old settlers of Anglo-Norman origin the new plantations constituted a grave political danger. Notwithstanding their loyalty they had long been feeling dissatisfied with their position. More than once they had formally protested against the unconstitutional methods of the Irish Government, and had insisted on the recognition of their rights as Englishmen.

James VI & I (1566-1625) King of Scots from 24 July 1567. On 24 March 1603, he became King of England and Ireland as James I. He succeeded his mother Mary, Queen of Scots, who had been compelled to abdicate in his favour. In 1603, he succeeded the last Tudor monarch of England and Ireland, Elizabeth I, who died without issue. James, in line with other monarchs of England of the time, also claimed the title King of France, although he did not actually rule France |

|

Unfortunately for the favorable

consideration of their demands and the development of constitutional government

they were almost to a man Roman Catholics. Their hopes that with the accession

of James I their position would undergo a change for the better had been

disappointed; and, as the determination of Government to enforce the Act of

Uniformity became unmistakable, they could not close their eyes to the danger

that menaced them through the ever-rising tide of Protestant immigration. As

symptomatic of the change that had come over them, it was noticed by a

contemporary writer that whereas “until of late, the old English race, as well

in the Pale as in other parts of the kingdom, despised the mere Irish,

accounting them a barbarous people void of civility and religion”, now “the

slaughters and rivers of bloodshed between them are forgotten”, “and, lastly,

their union is such, as not only the old English dispersed abroad in all parts

of the realm, but the inhabitants of the Pale, cities and towns are as apt to

take arms against us (which no precedent time hath ever seen) as the ancient

Irish”. A common religious belief has furnished the cement to many strange

alliances; and in Ireland, where religion was becoming more and more the

touchstone of national life, it was little wonder if, in face of the danger

menacing them, the gentry of the Pale should have thought their only chance of

safety lay in a union with the native element. Whether the bond of religion

would prove strong enough to withstand the dissolving influences of social and

racial differences, it was for the future to decide.

It is significant of that strange antithesis between respect for the

letter of the law and indifference to its spirit, which ever and again shows

itself in the history of the English rule in Ireland, that, after wresting six

entire counties from the Irish by more or less equivocal methods, the

Government of James I should have thought it necessary to secure the assent of

Parliament to its proceedings. Still, if it had been merely a question of

obtaining a parliamentary confirmation of the plantation, precedents were not

wanting from Elizabeth’s reign to show that it might have been accomplished

without resorting to any methods that went beyond the constitution. But the

known intention of the Government to propose fresh measures of penal

legislation against the Catholics, and the natural apprehension that the

opportunity would be seized to use the plantation for securing a Protestant

majority in Parliament, forced the gentry of the Pale into a position of

extreme hostility to the Crown, when its intention of exercising its right to

create some forty new boroughs became known. In itself there was indeed nothing

very outrageous in this exercise of the royal prerogative; and, if some of the

newly-created boroughs were hardly to be found on the map, there was in this

respect, as James shrewdly remarked, no very great difference between them and

many of the older ones. The real objection was of course that they were merely

Government pocket-boroughs.

In announcing (November, 1611) the King’s intention to summon a Parliament, Chichester, with an appearance of the utmost candor, invited the nobility of the Pale to confer with one another as to the measures they thought necessary to pass for the benefit of the country.

Poynings' Law, it was initiated by Sir Edward Poynings in the Irish Parliament at Drogheda in 1494. In his position as Viceroy to Ireland and Lord-Deputy, as appointed by King Henry VII of England, coming in the aftermath of the divisive Wars of the Roses, assembling the Parliament on 1 December 1494, he declared that the Parliament of Ireland was thereafter to be placed under the authority of the Parliament of England. The Act remained in place until the Constitution of 1782 gave the Irish parliament legislative independence. |

This they refused to do, urging their right, according to a doubtful interpretation of a clause in Poynings’ Act, to be made acquainted as part of the Council of the realm with the measures intended to be passed in Parliament. But, finding Chichester absolutely determined not to admit their claim and confirmed in their worst anticipations of further penal legislation by the public execution or martyrdom, in February, 1612, of Cornelius O’Devany, Catholic Bishop of Down and Connor, they addressed in November a strong remonstrance to the King.

O'Dovany, or O'Devany, Cornelius, embraced the rule of St. Francis in his youth, and was consecrated Bishop 27th April 1582. He was imprisoned in Dublin Castle for some three years preceding 1590, being obliged at times to keep himself alive by drawing up crusts of bread through a hole in the floor from other prisoners confined beneath him. After being at liberty for several years, he was again arrested in June 1611, on the charge of having assisted Hugh O'Neill with his counsel during his wars, and aided him in his flight to the Continent. In the face of a strong alibi, and the provisions of a recent Act of oblivion, he was sentenced to death, and suffered in company with the Rev. Patrick Locheran, his friend and companion, in a field near Dublin, 1st February 1612. They met their doom with fortitude, and after being half-hanged, were subjected to the barbarities then attendant on executions for high treason. The following night the bodies were dug up from beneath the foot of the gallows, and buried within the precincts of a neighbouring chapel. |

In it

they complained that they had not been consulted by the Deputy as the statute

required, and that the erection of corporations “consisting of some few and

beggarly cottages” could “tend to naught else... but that... penal laws should

be imposed upon your subjects”. No attention was paid to this protest; and in

April, 1613, the elections took place amid great excitement. No sooner had

Parliament met on May 18 and a motion to elect Sir John Davis Speaker been

made, than the long pent-up storm broke loose. On the ground that Davis, having

no residence in county Fermanagh, had been improperly

returned as a knight of that shire, the Opposition insisted on scrutinizing all

elections before proceeding to any other business. But, allowing themselves to

be persuaded to nominate a candidate of their own, and letting their choice

fall on Sir John Everard, the supporters of Sir John

Davis, following English precedent, retired from the chamber to tell their numbers.

During their absence the Opposition declared Everard elected and placed him in the chair. Apprised of what had happened, the

Government party finding themselves in the majority returned in hot haste, and,

having ejected Everard, installed Davis in his place.

Hereupon the Opposition, declining to take further part in the Parliament,

withdrew. Their friends in the Upper House made common cause with them; and Chichester, after vainly trying to effect a compromise,

yielded to their request to allow them to send a deputation to submit their

complaints to the King. In the meantime he prorogued Parliament.

The petition resolved itself into an elaborate attack on Chichester’s administration. It was, as James

confidentially admitted, a specious document; and, though he was convinced that

it was all a piece of Jesuitry, yet, inasmuch as he

was anxious that his Irish subjects should learn “rather to address themselves

to the sovereign by humble petition ...than, after the old fashion of that

country to run out, upon every occasion of discontent, to the bog and wood”, he

thought it advisable to appoint a Commission to investigate their complaints.

How far his impartiality extended was seen from his nominating Chichester head of a Commission. It reported on November 12;

and on April 20, 1614, James read the Irish deputation a severe lecture on

their undutiful and disgraceful behavior. Their charges against Chichester he pronounced wholly unfounded; and all that, as

a matter of grace, he would concede was the temporary disfranchisement of

several boroughs, provided the petitioners consented to sign a formal

instrument of submission.

But the opposition which he had encountered gave James reason to pause;

and when Chichester reopened Parliament in October he

was authorized to announce that the Bill against the Jesuits had been

withdrawn. The concession worked favorably on the Catholics; and under Sir John Everard’s leadership they offered no further

resistance to Government. With their support a subsidy Bill was passed in the

following session, and there was every prospect that with a little goodwill on

both sides a reasonable compromise might have been effected. Unfortunately at

this juncture Parliament was dissolved and Chichester recalled.

Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Chichester (1563-1625), Lord Deputy of Ireland from 1604 to 1615. His career in Ireland began when the Earl of Essex appointed him Governor of Carrickfergus in 1598, upon the death of his brother Sir John Chichester. John Chichester had been killed at the Battle of Carrickfergus the previous year. It is said that John Chichester was decapitated, his head being used as a football by the MacDonnell clan after their victory. James Sorley MacDonnell, commander of the clan's forces at the Battle of Carrickfergus, was poisoned in Dunluce Castle on the orders of Robert Cecil to placate Chichester. During the Nine Years' War he commanded crown troops in Ulster. His tactics included a scorched earth policy. He also encircled O'Neill's forces with garrisons, effectively starving the Earl's troops. In a 1600 letter to Cecil he stated "a million swords will not do them so much harm as one winter's famine". While these tactics were not initially devised by Chichester, he carried them out ruthlessly, gaining a hate-figure status among the Irish. In 1604 he succeeded Lord Mountjoy as Lord Deputy of Ireland. A year later he married Lettice Perrot. She was the daughter of John Perrot, a former Lord Deputy of Ireland. They had one child the following year, who died in infancy. Lord Deputy Chichester saw Irish Catholicism as a major threat to the crown. He oversaw widespread persecution of Catholics, and ordered the execution of two bishops.

Following the Flight of the Earls in 1607, Chichester was a leading figure during the Plantation of Ulster. Initially he intended that the number of Scottish planters would be small, with native Irish landowners gaining more land. However, after a rebellion in Donegal in 1608, his plans changed and all the native lords lost their land. Most of the land was awarded to wealthy landowners from England and Scotland. However Chichester successfully campaigned to award veterans of the Nine Years' War land as well, funded by the London Livery Companies.

Chichester was instrumental in the founding and expansion of Belfast, now Northern Ireland's capital. In 1611 he built a castle on the site of an earlier 12th century Norman Motte-and-bailey. In 1613 he was given the title Baron Chichester of Belfast. In 1614 ill health led to his retirement. In his final years be built a mansion in Carrickfergus and served as an ambassador to the Habsburg Empire. He died from pleurisy in London in 1625. He was buried seven months later in St Nicholas' Church, Carrickfergus. The barony of Chichester became extinct on his death but was revived the same year in favour of his younger brother Edward. Edward's son was also named Arthur Chichester and was the first Earl of Donegall. The family's influence in Belfast is still evident. Several streets are named in their honour, including Donegall Place, site of the Belfast City Hall and the adjacent Chichester Street. |

1626-34] The “Graces”. Wentworth

appointed Deputy.

Where he had failed, there was little reason to expect that either Sir

Oliver St John (1616-22), or Lord Falkland (1622-9), would prove more

successful, hampered as they were in their anti-Catholic line of policy by

having to regulate their conduct according as the wind blew from Spain or in a

contrary direction, and by the perennial bankruptcy of the Irish treasury. The

time had passed away when the Counter-reformation could be dammed in by shilling

fines for non-attendance at church and futile proclamations for the banishment

of the Catholic clergy. Such proceedings and the constant rummaging of the land

for plantation purposes served only to irritate. Year by year the dissatisfaction

grew; and in 1626 it was more than doubtful whether Government could command

the majority in Parliament which it had possessed ten years earlier. Anyhow,

the experiment was one that Charles preferred, if possible, to avoid. But, with

a war with France likely to be added to that with Spain, it was imperative that

Ireland, which was openly spoken of as the backdoor to England, should be put

in a posture of defence. For this purpose Falkland was authorized (September,

1626) to sound the nobility and gentry as to their willingness, in return for

certain valuable concessions, to undertake on behalf of the country to maintain

an army of 5000 foot and 500 horse. These concessions, known as the “Graces”,

were skillfully contrived so as to appeal to the interests of every class in

the community and were coupled with the promise of a speedy confirmation by

Parliament. To the Catholic landowner in Connaught (map) in particular, whom fear of

a plantation kept in a constant state of anxiety, the offer of the Crown to

accept sixty years’ possession as a bar to all claims came as a special boon.

Nevertheless, so general was the repugnance to this extra-parliamentary method

of taxation that the agents representing the landed gentry only with the

greatest difficulty could be induced (May, 1628) to bind the country to

contribute £120,000, to be spread over three years, and to be deducted from

whatever subsidies might be granted by Parliament. The contribution began at

once; and Falkland in fulfillment of his part of the transaction made

preparations for calling a Parliament. But whether Charles deliberately meant

to cheat the nation, or whether, as seems more likely, his courage to confront

the difficulties of the situation evaporated, time went by, and no Parliament

was summoned. In 1629 Falkland was recalled. By reducing the army one-half and

by exercising the strictest economy his successors, the Lords Justices Loftus

and Cork, managed to spread the contribution over four years. The neglect to

call a Parliament was, however, an irreparable blunder, not merely because it

rendered such contributions precarious in the future, but chiefly because, by

weakening the general confidence in the sincerity of Government, it created a

situation of which the Jesuits were not slow to take advantage. Indeed the only

interest which the period possesses is that which attaches to the extraordinary

progress made in it by Roman Catholicism. The fact is bewailed in nearly every

State-paper of the time; but, beyond knocking down a few mass-houses and

digging up St Patrick's purgatory, the Lords Justices could suggest no means of

counteracting it. Without the courage, and perhaps the will, to take the only

step that promised safety they looked on helplessly, while the country drifted

into anarchy.

Charles I (11600-1649) second son of James VI of Scots and I of England. King from 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles believed was divinely ordained. Many of his English subjects opposed his actions, in particular his interference in the English and Scottish Churches and the levying of taxes without parliamentary consent which grew to be seen as those of a tyrannical absolute monarch. His failure to successfully aid Protestant forces during the Thirty Years' War, coupled with such actions as marrying a Catholic princess, generated deep mistrust concerning the king's dogma. Charles further allied himself with controversial religious figures, such as the ecclesiastic Richard Montagu, and William Laud, whom Charles appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. Many of Charles' subjects felt this brought the Church of England too close to the Catholic Church. Charles' later attempts to force religious reforms upon Scotland led to the Bishops' Wars, strengthened the position of the English and Scottish Parliaments and helped precipitate the king's downfall. Charles' last years were marked by the English Civil War, in which he fought the forces of the English and Scottish Parliaments, which challenged the king's attempts to overrule and negate Parliamentary authority, whilst simultaneously using his position as head of the English Church to pursue religious policies which generated the antipathy of reformed groups such as the Puritans. Charles was defeated in the First Civil War (1642–45), after which Parliament expected him to accept its demands for a constitutional monarchy. He instead remained defiant by attempting to forge an alliance with Scotland and escaping to the Isle of Wight. This provoked the Second Civil War (1648–49) and a second defeat for Charles, who was subsequently captured, tried, convicted, and executed for high treason. The monarchy was then abolished and a republic called the Commonwealth of England, also referred to as the Cromwellian Interregnum, was declared. Charles I was canonised as Saint Charles Stuart and King Charles the Martyr by the Church of England and is venerated throughout the Anglican Communion. |

Such was the situation of affairs in January, 1632, when Charles

announced the appointment of a new Deputy. More than a year and a half elapsed

before Wentworth landed at Ringsend; but his

influence had long before then made itself felt in the affairs of the country.

With the single object before him of making Ireland a source of strength to the

Crown instead of one of weakness, as it had hitherto been, he succeeded, by

alternately playing on the fears and hopes of the Catholic party and flattering

the loyalty of the Protestants, in obtaining a prolongation of the contribution

for two years. Thus he secured for himself breathing-space in which to develop

his policy. Starting with the axiom that a prosperous people is also a loyal

people, Wentworth bent all his energies to the development of the natural

resources of Ireland. And it must be said for him that, if in trying to

accomplish his purpose he spared no one who ventured to oppose him, neither did

he spare himself. His eye was everywhere. If the exportation and manufacture of

wool had to be discouraged as detrimental to the staple trade of England, he,

by way of compensation, personally superintended the development of the linen

industry, and insisted on a free export of hides and tallow. He arranged the

details of a commercial treaty with Spain, calculated to encourage the fishing

industry; he brought over experts to explore the mineral resources of the

country; laid down stringent regulations for the preservation of the rapidly

disappearing forests; exerted himself to improve the breed of cattle; cleared

the narrow seas of the pirates that infested them and rendered commerce

insecure; and, by buying out all private interests detrimental to the Crown,

succeeded in more than doubling the revenue of the State. Knowing the value of

order and decorum in public life, he insisted on a strict observance of Court

etiquette; repaired Dublin Castle; cleared out the wine-vaults under Christ

Church; and by his own example infused a spirit of emulation in the army which

shortly raised it to the highest pitch of efficiency. For the rest, he was

content to bide his time. What he could do to realize his friend Laud’s wishes

in the matter of ecclesiastical uniformity and discipline by pressure on the

episcopacy, and to restore dignity to the Church by the recovery of its

property, he did. But it was no part of his policy to irritate the Catholics by

fining them for non-attendance at church when, as was too often the case, there

was no church for them to attend. Doubtless he made many enemies by his policy

of “thorough”; but in his struggle with Cork, Wilmot, Mountnorris,

Crosby, and the rest, we cannot deny him a certain measure of sympathy. Under

his controlling hand Ireland emerged from the state of anarchy into which she

had drifted, and, feeling confident of his ability to steer an independent

course, he obtained Charles’ reluctant consent to risk a Parliament.

The event more than answered his expectations. Parliament met on July

14, 1664. It was the most splendid scene Dublin had ever witnessed. In his

opening speech Wentworth announced the King’s intention to hold two sessions,

the one for himself, the other for the benefit of his subjects. The proposal to

separate grievances from supply was agreeable to neither Catholics nor

Protestants; but so evenly balanced were they that, as Wentworth put the case,

neither party would allow the other to rob it of applying the whole grace of

His Majesty’s thanks to itself. Hence, when the motion for supply was made,

both “did with one voice assent to the giving of six subsidies to be paid in

four years”. But, if the Commons ever imagined that their loyalty would be rewarded

by a candid confirmation of the long-promised Graces, they were speedily

disabused of the idea. There was nothing on which Wentworth depended more for

an improvement of the revenue than a new plantation and a strict revision of

the old ones. He was therefore determined at any cost to prevent the

confirmation of any Grace which threatened to cross his purpose, and

particularly of that which accepted sixty years’ possession as a bar to all

claims on the part of the Crown. To this end he divided the Graces into three

classes : viz. those which he thought not fit to be granted, those which might

be continued by way of instruction, and those proper to be passed into laws. By

neglecting, as by Poynings’ Law he was able to do, to

transmit any except those in the last class, he transferred all responsibility

in the matter from the Crown to himself and the Irish Council.

When Parliament reassembled in

November the indignation of the Catholics knew no bounds, and finding

themselves accidentally in the majority, they rejected without consideration

all and every measure submitted to them. For a moment Wentworth thought of

adjourning Parliament; but the Protestants came to his rescue and enabled him to

bring the session to a satisfactory conclusion. For the next four years his

course was clear; and with characteristic energy he at once took up his

plantation project.

Hitherto, however they might have answered their purpose of substituting

a British for a native proprietary, the plantations had proved singularly

unprofitable to the Crown. Not only had vastly more land, for which they of

course paid no rent, been passed to the undertakers than was set out in their

patents, but their eager haste to turn their estates to immediate profit had

led to such a general breach of the conditions of plantation as constituted a

serious danger to the State. So notoriously was this the case in regard to the

London Society that in 1632 the Star Chamber had ordered the suspension of its

charter and the sequestration of its rents. Though not responsible for this

step, Wentworth fully approved it; and, on the confiscation of the Society’s

Charter in 1635, he suggested the conversion of its estates into an appanage for the Duke of York. But the Londoners were not

the only offenders; and, though it was impossible to deal with private

individuals in the same drastic fashion without imperiling the whole

settlement, the Commission for the remedy of defective titles was admirably

contrived to make them pay handsomely for their defaults and at the same time

to teach them a salutary lesson for the future. As for the plantations which he

intended himself to set on foot in Connaught and elsewhere, though

inconsiderable in comparison with those already established, he hoped, by a

stricter admeasurement of land and by making estates only in capite, to render them not less

profitable to the Crown, and by at the same time restricting them to English

undertakers, to create a counterpoise to the Scottish settlers in the north.

For himself, he was perfectly convinced of the validity of the Crown’s title to

the lands he intended to plant; but, wishing to give an air of legality, not to

say of beneficence, to his proceedings by eliciting a voluntary recognition

from the reputed landowners in question, he was enraged beyond measure when the

jurors of Galway county, declining to follow the lead of those of Roscommon, Sligo, and Mayo, refused to find a title for the King. It

was a comparatively easy matter to punish them in the Court of Castle Chamber

and by an order in the Court of Exchequer to procure a reversal of their

verdict; but all this required time, and, before things could again be brought

into order, his attention was absorbed by more important matters.

New plantations. The

Scottish Rebellion. [1637-40

|

The little cloud which had been gathering over Edinburgh in the summer

of 1637 had spread with such alarming rapidity as at the beginning of the

following year to cast its shadow over Ireland also. From Scotland the

contagion of the Covenant had spread to Ulster, and, faster than either he or

his chief ecclesiastical agent, Bishop Bramhall, was

aware, the country was slipping out of his control. As the prospect of war between

England and Scotland grew more certain, and it became necessary to reckon up

his resources, Charles was unreasonably annoyed when reminded that the Irish

army barely sufficed to guarantee order in Ireland itself; and, while accepting

the Deputy’s offer of 500 men to garrison Carlisle, he could not avoid

contrasting the scanty help thus furnished him with the recent magnificent

promise of the Earl of Antrim to attack Argyll in his own country with 10,000

men. It was ever Charles’ misfortune to be unable to look facts fairly in the

face; and, finding it impossible to convince him that Antrim’s offer was merely

intended as a “handsome compliment”, Wentworth moved the bulk of the army to Carrickfergus, by way of giving what countenance he could

to the project.

The Treaty of Berwick (also known as the Peace of Berwick or the Pacification of Berwick) was signed on 18 June 1639 between England and Scotland. Archibald Johnston was involved in the negotiations before King Charles was forced to sign the treaty. The agreement, overall, officially ended the First Bishops' War even though both sides saw it only as a temporary truce. After the treaty was signed, King Charles immediately began to gather the resources he needed in order to strengthen his armies. At the beginning of the Second Bishops' War, the agreement was broken. After a disastrous skirmish at Kelso between the English advance guard and the Scottish Covenanter Army, the Earl of Holland fled back to the king’s headquarters at Berwick-upon-Tweed. The Earl of Antrim failed to establish negotiations in order to bring the Irish army over. This, along with the unsuccessful English naval campaign at Hamilton, meant that Charles was forced to sign a truce. He conceded to the Scots the right to a free church assembly and a free parliament. These rights were asserted (with the right to keep the existing legal structure instead of a separate parliament) along with the extension to Scotland of The Bill of Rights (which set out the conditions and powers of a monarch) in the Treaty of Union, 1707, which united England and Wales with Scotland. |

The Treaty of Berwick afforded a slight breathing-space; and, the Deputy’s quarrel with Lord Chancellor Loftus having brought him to London in September, 1639, Charles eagerly turned to him for advice. Wentworth’s remedy was a Parliament. He remembered how, when everybody had predicted failure, he had been splendidly successful in Ireland in 1634. Let Charles follow his example: he was convinced that no Englishman would refuse money for driving the Scots out. To hearten the experiment he would himself hold a Parliament in Ireland; of the result there could be no doubt. How little he knew his own countrymen was soon to appear; but so far as Ireland was concerned his experiment was crowned with success. He returned to Dublin Earl of Stafford. Parliament was already in session. On March 23, 1640, the Commons with one voice voted four subsidies, or £180,000. Never had such a scene of unanimity been witnessed; hats were thrown in the air and assurances given that if more money was wanted more would be forthcoming, even if they left themselves nothing but hose and doublet.

Christopher Wandesford (1592 – 1640), Lord Deputy of Ireland, |

|

Overjoyed at his victory,

Strafford, after appointing Sir Christopher Wandesforde his deputy and leaving instructions with the Earl of Ormonde to add 8000 men to

the army, hastened back to England. He had calculated that the example of the

Irish Parliament would find imitation in England; he had not considered that

the conduct of the English Parliament might cause a reaction in Ireland. But it

was no sooner evident that the day of his power was over than the Commons of

Ireland joined with their brethren in England to bring the fallen Minister to

justice. To Strafford’s plea of good government they replied with a

remonstrance under fifteen heads, which formed the backbone of his impeachment.

For a time the universal hatred with which he was regarded kept them unanimous.

Pillar after pillar of the building which he had raised with so much care was

thrown to the ground amid general applause. Step by step the country drifted

back into the state of anarchy from which he had rescued it. The Nemesis that

lies in wait for despotism had overtaken the policy of “thorough”. On November

12 Parliament was adjourned to January 26, 1641. During the recess Wandesforde died, and after some wrangling Sir William

Parsons and Sir John Borlase were appointed Lords

Justices. In Parsons the new settlers had obtained a ruler after their own

hearts.

Meanwhile all eyes were directed

to the army, which under Strafford’s instructions Ormonde had raised to nearly

10,000 men. “You have an army in Ireland you may employ here to reduce this

kingdom”, Strafford was reported to have advised Charles. Whether “this kingdom”

meant England or Scotland might be disputed, but there could be no question as

to the deadly insult to public opinion implied in the suggestion. No words can

adequately express the loathing and utter abhorrence which the mere suggestion

of employing Irish soldiers in England excited in the breasts of Englishmen. To

the demand of the English Commons for its instant disbandment Charles returned

an absolute refusal. The fact was that the Irish army was beginning to assume a

new importance to him, as the idea of playing off the Irish Catholics against

the English Parliament took hold of his mind. Granted that he could detach the

Scots from their bond with the Parliament, which was his immediate object, it

would not, he imagined, be impossible by conceding the Graces and by extending

practical toleration to the Catholics to win over the Irish Parliament to his

side. Scotland and Ireland conciliated, the Irish army would materially

strengthen his hands in dealing with the English Parliament. It was therefore

of the utmost importance that it should be kept together. His intentions were

suspected, and being driven to consent to the disbandment of the new levies he

tried a middle way by issuing warrants for their transportation to Spain.

Origin and outbreak of

the Rebellion. [1641

|

Curiously enough, this step was strongly opposed by both parties in the

Irish Parliament : by the Protestants on the ground that, in case of invasion,

it was extremely dangerous to permit so many Irishmen well acquainted with

every creek and haven in the kingdom to enter the Spanish service; by the

Catholics on the ground that it was the height of madness to allow so many men

to leave the country when its liberties were menaced by English Puritans and

Scottish Presbyterians. The difficulty of finding money to pay their arrears

caused some delay; but towards the end of July this obstacle was overcome, and

the soldiers were already assembling at the ports appointed for their

embarkation, when secret instructions arrived from Charles to the Earls of

Ormonde and Antrim, requiring them to keep the army together, and if possible

to raise its strength to 20,000 men. The message arrived too late; and an

express sent to inform the King of the fact found him at York on his way to

Scotland. From York the order came to get the men together again and hold them

in readiness, if the occasion arose, to declare for the King. The officers in

charge of the disbanded soldiers readily fell in with the plan; and steps were

taken to sound the gentry of the Pale and the leaders of the old Irish as to

their views on the subject.

It was at this point that the

plot, if we may so designate a movement authorized by the King, ran into

another of quite independent origin. We know now, what no one at the time

suspected, that a rebellion had long been brewing in the north, having for its

object the recovery of Ulster and ultimately of Ireland for the Irish, and

depending for its success on support promised by Owen Roe O’Neill, commanding

in the Spanish service in the Low Countries. On him, since definite tidings had

arrived of the death of John O’Neill, commonly called the “Conde de Tirone”, before Monjuich, the mantle of leader had

fallen. Everything had been prepared, and only the opportunity was wanting for

a general rising in Ulster. To Rory O'More, Lord Maguire,

and the other northern conspirators nothing could therefore have happened more

in accordance with their wishes than the chance thus afforded them of

accomplishing their own designs under color of assisting in a quasi-legal plot.

It was the cue of the King’s party to lie quiet and wait instructions; but, as

September drew to a close, a rumor got about that the plot was abandoned, and O’More and Maguire reverted to their old plan.

At a meeting of the conspirators

on October 5 the rising was finally fixed for Saturday the 23rd. The rebellion

broke out simultaneously all over Ulster on the day appointed. The attempt to

capture Dublin failed. Derry, Coleraine, Lisburn, Carrickfergus, Enniskillen escaped; but Dungannon, Charlemont, and Newry were

captured by the rebels. There was no general massacre; but everywhere the

colonists were turned out of house and home, stripped of their possessions, and

too often left without a rag to cover their nakedness. Large numbers perished

of cold, hunger, and ill-treatment; and many, there is no doubt, were butchered

in cold blood; but the great majority managed to escape.

The Rebellion took everyone by surprise, none more so than the quondam

allies of Maguire and O’More. Charles, whose

conscience may perhaps have reproached him for his share in the mischief, and

who was really alarmed when he heard that the rebels were pretending to act by

his authority, was the first to insist on active measures being taken for their

suppression. And, indeed, had Government shown a firm hand, the rebellion might

easily have been confined to Ulster. Munster, Connaught, and Leinster showed at first no signs of rising. The Catholic

gentry of the Pale, though ready enough to countenance any coup d’état which promised to secure them a practical toleration of

their religion, together with a recognition of their proper position in the

State, were by no means anxious to throw themselves into a movement which

seemed likely to be attended with little advantage to themselves and which was

already discredited by its barbarity. Even in Ulster itself the ease with which

the colonists, after they had recovered from their first surprise, were able to

hold their own, was evidence enough that with a little courage the rebellion

might have been crushed in its beginning. Unfortunately the Government was not

prepared to act vigorously. The Lords Justices, who had saved themselves as it

were by a miracle, seemed to have lost their senses entirely. Their first

impulse to trust the Catholic gentry by providing them with arms to defend

themselves yielded to an ill-defined dread lest they might thereby be arming

their enemies. They could think of no action beyond putting Dublin in a state

of defence, concentrating all the available troops in the neighborhood, laying

waste the districts around, and husbanding their resources until their piteous

appeals for help from England were answered. Judging from their conduct it

might have seemed as if they were rather anxious than otherwise to force a

general insurrection. This at any rate was its effect. For, finding themselves

so utterly distrusted and unable to maintain a position of neutrality, the

gentry of the Pale, impelled by their fears and encouraged by the defeat of a

small force detached for the relief of Drogheda and the apparent impossibility

of that town holding out against the forces investing it, finally, in December,

threw in their lot with the northern rebels. In announcing the fact to their friends

in England, the Lords Justices warned them against attaching too much

importance to what they called the defection of “seven Lords of the Pale”. For,

though it might seem to add some reputation to the rebels, they who knew that

their tenants and followers had long before gone over to the rebels knew that

it added no real strength to them. This point they desired to emphasize, lest

the State might be misled into consenting to conditions injurious to His Majesty,

when on the contrary “their discovering of themselves now will render advantage

to His Majesty and those great counties of Leinster,

Ulster, and the Pale now lie the more open to His Majesty’s free disposal and

to a general settlement of peace and religion by introducing of English”. As

the event proved, the Lords Justices erred greatly in their forecast of the

probable consequences of the defection of the Pale; but their suggestion of a

new plantation did not miss its calculated effect.

O'Neill was the son of Art O'Neill, a younger brother of Hugh O'Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone (the Great O'Neill), who held lands in County Armagh. As a young man he left Ireland, one of the ninety-nine involved in the Flight of the Earls escaping the English conquest of his native Ulster. He grew up in the Spanish Netherlands and spent 40 years serving in the Irish regiment of the Spanish army. He saw most of his combat in the Eighty Years' War against the Dutch Republic in Flanders, notably at the siege of Arras, where he commanded the Spanish garrison. He also distinguished himself in the Franco-Spanish war by holding out for 48 days with 2,000 men against a French army of 35,000. O'Neill was, like many Gaelic Irish officers in the Spanish service, very hostile to the English Protestant presence in Ireland. In 1627, he was involved in petitioning the Spanish monarchy to invade Ireland using the Irish Spanish regiments. O'Neill proposed that Ireland be made a republic under Spanish protection to avoid in-fighting between Irish Catholic landed families over which of them would provide a prince or king of Ireland. This plot came to nothing. However in 1642, O'Neill returned to Ireland with 300 veterans to aid the Irish Rebellion of 1641. The subsequent war, known as the Irish Confederate Wars, was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms -civil wars throughout Britain and Ireland. Because of his military experience, O'Neill was recognised on his return to Ireland, at Doe Castle in Donegal (end of July 1642), as the leading representative of the O'Neills and head of the Ulster Irish. Sir Phelim O'Neill resigned the northern command of the Irish rebellion in Owen Roe's favour, and escorted him from Lough Swilly to Charlemont.But jealousy between the kinsmen was complicated by differences between Owen Roe and the Catholic Confederation which met at Kilkenny in October 1642. Owen Roe professed to be acting in the interest of Charles I; but his real aim was the complete Independence of Ireland as a Roman Catholic country, while the Old English Catholics represented by the council desired to secure religious liberty and an Irish constitution under the crown of England. More concretely, O'Neill wanted the Plantation of Ulster overturned and the recovery of the O'Neill clan's ancestral lands. Moreover, he was unhappy that the majority of Confederate military resources were directed to Thomas Preston's Leinster Army. Preston was also a Spanish veteran but he and O'Neill had an intense personal dislike of each other. Although Owen Roe O'Neill was a competent general, he was outnumbered by the Scottish Covenanter army that had landed in Ulster in 1642. Following a reverse at Clones, O'Neill had to abandon central Ulster and was followed by thousands of refugees, fleeing the retribution of the Scottish soldiers for some atrocities against Protestants in the rebellion of 1641. O'Neill complained that the devastation of Ulster made it look, "not only like a desert, but like hell, if hell could exist on earth". O'Neill did his best to stop the killings of Protestant civilians, for which he received the gratitude of many Protestant settlers. From 1642-46 a stalemate existed in Ulster, which O'Neill used to train and discipline his Ulster Army. This poorly supplied force nevertheless gained a very bad reputation for plundering and robbing friendly civilians around its quarters in northern Leinster and southern Ulster. In 1646 O'Neill, furnished with supplies by the Papal Nuncio, Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, attacked the Scottish Covenanter army under Major-General Robert Monro, who had landed in Ireland in April 1642. On 5 June 1646 O'Neill utterly routed Monro at the Battle of Benburb,[1] on the Blackwater killing or capturing up to 3000 Scots. However after being summoned to the south by Rinuccini, he failed to take advantage of the victory, and allowed Monro to remain unmolested at Carrickfergus. In March 1646 a treaty was signed between Ormonde and the Catholics, which would have committed the Catholics to sending troops to aid the Royalist cause in the English Civil War. The peace terms however, were rejected by a majority of the Irish Catholic military leaders and the Catholic clergy including the Nuncio, Rinuccini. O'Neill led his Ulster army, along with Thomas Preston's Leinster army, in a failed attempt to take Dublin from Ormonde. However, the Irish Confederates suffered heavy military defeats the following year at the hands of Parliamentarian forces in Ireland at Dungans Hill and Knocknanauss, leading to a moderation of their demands and a new peace deal with the Royalists. This time O'Neill was alone among the Irish generals in rejecting the peace deal and found himself isolated by the departure of the papal nuncio from Ireland in February 1649. So alienated was O'Neill by the terms of the peace the Confederates had made with Ormonde that he refused to join the Catholic/Royalist coalition and in 1648 his Ulster army fought with other Irish Catholic armies. He made overtures for alliance to Monck, who was in command of the parliamentarians in the north, to obtain supplies for his forces, and at one stage even tried to make a separate treaty with the English Parliament against the Royalists in Ireland. Failing to obtain any better terms from them, he turned once more to Ormonde and the Catholic confederates, with whom he prepared to co-operate more earnestly when Cromwell's arrival in Ireland in August 1649 brought the Catholic party face to face with serious danger. Before, however, anything was accomplished by this combination, Owen Roe died on 6 November 1649 at Clough Oughter castle in County Cavan. The traditional Irish belief was that he was poisoned by the English, but now some believe it is more likely that he died of disease. Under cover of night he was buried in the Franciscan friary at nearby Cavan town. His death was a major blow to the Irish of Ulster and was kept secret for some time. The Catholic nobles and gentry met in Ulster in March to appoint a commander to succeed Owen Roe O'Neill, and their choice was Heber MacMahon, Roman Catholic Bishop of Clogher, the chief organizer of the recent Clonmacnoise meeting. O'Neill's Ulster army was unable to prevent the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, despite a successful defence of Clonmel by Owen Roe's nephew Hugh Dubh O'Neill and was destroyed at the Battle of Scarrifholis in Donegal in 1650. Its remnants continued guerrilla warfare until 1653, when they surrendered at Cloughoughter in county Cavan. Most of the survivors were transported to serve in the Spanish Army. |

Measures of the English

Parliament. [1641-2

Meanwhile the rebellion had been seriously occupying the attention of

all parties in England. On the main point all were of one opinion; and, had it

been simply a question between England and Ireland, money and men would have

been speedily forthcoming to gratify the national desire for revenge. In the

first flush of its wrath, the House of Commons voted that 10,000 foot and 2000

horse should forthwith be raised for its suppression and that the offer of

Scottish assistance should be accepted. Gradually cooler counsels prevailed.

The more the leaders of the parliamentary party came to know of Charles’ intrigues,

the more they were convinced that the Irish rebellion was only part of the

general problem they were trying to solve. To place a victorious army in

Charles’ hands was merely to fashion an instrument for their own destruction :

until security was obtained on this point nothing of importance could be done.

Towards the end of December Sir Simon Harcourt arrived at Dublin with 1500 men;

in February, 1642, Sir Richard Grenville brought 1500 foot and 400 horse to the

relief of the President of Munster; in April Robert Munro reached Carrickfergus with 2500 Scots. These forces, and a

contribution of £37,000, were the whole of the aid furnished to the Government

of Ireland during the first six months of the Rebellion. Meanwhile, however, no

opportunity was neglected of exasperating public opinion against the Irish, so

as to render a reconciliation between them and Charles impossible. On December

8, 1641, it was resolved that the King should be asked to declare that he would

never consent to a toleration of the popish religion in Ireland. On February 24

following, the Lords and Commons voted that, as several million acres of “profitable

lands” in Ireland were calculated to have been rendered liable to confiscation

by the Rebellion, the proposal of “divers worthy and well-affected persons” should

be accepted for raising £1,000,000 by the sale of “two millions and a half of

these acres, to be equally taken out of the four provinces of that kingdom” in

the proportion for each adventure of £200, £300, £450, and £600 of one thousand

acres in Ulster, Connaught, Munster, and Leinster respectively. On March 19 Charles was forced to give his consent to this atrocious

scheme of national robbery. With these two Acts the English Parliament closed

the door against any hope of reconciliation.

|

In Ireland, matters were not progressing favorably for the rebels. In

March their lack of artillery compelled them to raise the siege of Drogheda; a

month later the Earl of Ormonde inflicted a crushing defeat on them at Kilrush; in May they were driven out of Newry.

These and other disasters, though in a measure counterbalanced by the rapid

extension of the rebellion, did not fail to exercise a depressing influence on

the gentry of the Pale; and after the retreat of the northern rebels from

Drogheda they made a desperate effort to extract themselves from the critical

position into which their fears had driven them. But the Lords Justices, whom

success and the prospect of confiscation rendered pitiless, not only rejected

every overture for a compromise, but endeavored by every means within their

power to prevent any such offers from reaching the King. Orders were issued

that no quarter should be given to any rebel found in arms, and that the

commanders of garrisons should not grant protection to the Irish, or enter into

any treaty with them on any pretext whatever, but prosecute them from place to

place with fire and sword.

|

Finding the door of mercy thus resolutely closed upon them and the

Government bent on a war of extirpation, the gentry of the Pale took steps in

May to organize their resistance by appointing a Supreme Council of Nine to act

as a provisional government, pending the meeting of a General Assembly to

represent the nation at Kilkenny. Help for them was

already on the way. In July Owen Roe O'Neill arrived in Lough Swilly with a hundred veterans and considerable supplies of

arms and ammunition, and almost at the same time Thomas Preston and five

hundred men with artillery and other stores of war landed at Wexford. With

their arrival the rebellion passed out of the stage of sporadic insurrection

into that of regular warfare. On October 24 (1642), the day after the battle of Edgehill, the General Assembly of the Confederated

Catholics met at Kilkenny. It was virtually a

parliament of the Irish nation. But, regarding themselves as a merely

provisional assembly brought together under exceptional circumstances to devise

means for protecting themselves until His Majesty could take measures for their

preservation, the Confederates confined themselves to providing for the

administration of justice, the assessment of taxes, and the organization of

their military strength. The Supreme Council was reconstituted to consist of

twenty-four members, of whom twelve were to reside constantly at Kilkenny, or wherever they should judge most expedient, to

form a central and permanent government for the management of all affairs civil

and military. For the administration of local justice and carrying out the

behests of the Supreme Council, each county was provided with a separate

Council consisting of one or two deputies from each barony, and each province

with a provincial Council consisting of two deputies out of each county. For

military purposes each province was assigned its own army under its own chief

commander O'Neill in Ulster, Preston in Leinster,

Garret Barry in Munster, and John Bourke in Connaught. The form of government

having been thus settled and agents appointed to plead their cause at the

principal Courts in Europe, the General Assembly addressed two petitions, the

one to the King, explaining the reasons which had forced them to take up arms,

protesting their loyalty, and requesting permission to submit their grievances

to him; the other to the Queen, entreating her intercession with the King.

|

To Charles it would have been extremely satisfactory, if by coming to

terms with the Confederates he could have set free his army in Ireland to fight

his battles in England. The obstacles to such an agreement appeared, however,

insuperable. For quite apart from the fact that the Confederates were not

likely to recede from their demands for civil and religious liberty, any attempt

to come to terms with the “Irish murderers” was sure to raise a storm in

England and dash his hopes of raising a party in Scotland. Nevertheless, the

deplorable condition of the royal forces in Ireland justified him in pleading

military necessity for trying to obtain a cessation of arms. Influenced by

these considerations, he authorized Ormonde on January 11, 1643, to sound the

Confederates as to the precise nature of their demands, at the same time,

however, privately warning him that he could on no account consent to a

legislated toleration of the Roman Catholic religion, or to any claim for

parliamentary independence, such as a repeal of Poynings’

Law implied.

When the commission was opened at the Council Board, Parsons and others

strenuously opposed the proposal to treat, and, the Confederates taking

exception to the terms of the letter requiring them to appoint agents to submit

their grievances, the Lords Justices, in the hope of breaking off the

negotiations, managed with difficulty to get 1500 men in marching order. This

force they proposed to entrust to the command of Lord Lisle; but Ormonde, who

was tired of submitting to their dictation in military matters, insisted on

commanding himself. On March 18 he won a complete victory over Preston at Ross;

but owing to lack of provisions was compelled to return to Dublin without

reaping the fruits of his success. Meanwhile the Confederates had reconsidered

their position; and on the day before the battle they handed in a statement of

their grievances to the commissioners appointed to receive them. Their demand

for a new Parliament and religious toleration afforded little prospect of a

settlement. Quite apart from the opposition of men like Parsons, it was

generally felt that the concession of a free Parliament at that time would

imperil the entire English interest in the country. Nevertheless, it was clear

to any but the blindest partisan that, with the army on the verge of mutiny and

without a penny in the treasury, nothing but a cessation of hostilities could

save the situation.

1643-4] Cessation of

arms. Irish troops in England.

After his defeat at Ross Preston had rallied his forces, and in May

managed to capture Ballynakill. On June 4 Castlehaven inflicted a crushing defeat on Sir Charles Vavasour in Munster, and a fortnight later Galway Castle

capitulated to Colonel Bourke. Against these successes the Confederates had to

set the defeat of Owen O'Neill by Sir Robert Stewart at Clones; but Stewart had

been unable to improve his victory, and a week or two later O'Neill was as

strong as ever. Each day added to the difficulties of Ormonde’s position. In April Charles had written again, insisting on a cessation, and

Ormonde once more opened negotiations for a truce. But the Confederates, who

were fully alive to the strength of their position, persisted in their demand

for a new Parliament and for a thorough investigation of their grievances.

Unable to offer them any guarantee on these points, Ormonde once more appealed

to the sword. This time, however, Preston avoided giving battle; and Ormonde,

having convinced himself that there was nothing for it but a cessation, availed

himself of new orders that had reached him from Charles in July to reopen

negotiations. The attachment of Parsons and other prominent councilors of his

faction about the same time on a general charge of obstructing the King’s service

rendered his task easier; and on September 15 a cessation for twelve months was

concluded in order to enable the Confederates to submit their case personally

to Charles, and, as it was hoped, to arrange a permanent settlement with him.

Murrough McDermod O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin and 6th Baron Inchiquin (1614–1674), known as Murchadh na atoithean ("of the conflagrations"). O'Brien studied war in the Spanish service and fought against the confederate Catholics on the outbreak of the Irish rebellion. |

|

But, since the cessation had not been effected without considerable

friction among the Confederates themselves, and, as Carte candidly admits, “more

out of a sense of duty than policy”, so, no sooner was it proclaimed than it

was at once denounced by the adherents of the Parliament. The report of it

greatly injured the Royalist cause; but it enabled Charles to accomplish his

immediate purpose of setting free part of his army in Ireland. By the beginning

of Novemberfour regiments had arrived at Bristol from Munster, and more were

ready to follow as soon as Lord Inchiquin could find

means to transport them. In the same month 2000 men under Sir Michael Ernely landed in Flintshire to

form the nucleus of a small army under Lord Byron. But the assistance had been

dearly purchased. On January 25, 1644, Byron was defeated and his army routed

by Sir Thomas Fairfax at Nantwich. It was hard for

Charles to find his hopes thus dashed; but it was harder still to see these

same “Irish Papists”, for whom he had drawn upon himself the odium of his own

subjects, enlisting, after their defeat, in the service of his enemies. The

Irish danger had been averted; but Parliament was keenly alive to the necessity

of preventing such expeditions in the future by furnishing Ormonde with

sufficient occupation at home. While, therefore, a Scottish army under the Earl

of Leven prepared to invade England to assist the Parliament, messengers were dispatched

to Ulster to assure Munro and the northern commanders of the speedy arrival of

money and provisions, and to promote a general engagement to the Covenant.

Strange to say, Munro’s refusal to recognize the cessation was not distasteful

to Charles, who calculated, not without reason, that it would prevent any help

from that quarter reaching Leven. Moreover he was not without hope that, if

Antrim succeeded in transporting, as he professed himself able to do, 2000

redshanks into Scotland to cooperate with Montrose, Leven might speedily find

himself recalled. Hitherto Antrim had not proved very deserving of confidence;

but in July he actually managed, with Ormonde’s assistance, to land 1600 men in Scotland, where under the leadership of Alaster MacDonnell they not a little contributed to

Montrose's success.

Meanwhile the agents appointed by the Confederates to arrange the terms

of a settlement with Charles had arrived at Oxford in March. Conscious of their

improved position, they insisted on the repeal of all penal laws against the

Catholics, the abrogation of all acts and ordinances of the Irish Parliament

since August 7, 1641, the summoning of a freely elected Parliament, and a

general Act of Oblivion. These terms granted, they bound themselves to furnish

him with 10,000 men, and to expose their lives and fortunes in his service. But,

tempting as the offer was, it was impossible for Charles to consent to its

conditions without forfeiting the support of his own followers. In his dilemma

he referred the matter back again to Ormonde. But unfortunately, at the very

moment when it behoved him to strengthen the hands of

his much-tried Deputy by every means within his power, he had the inconceivable

folly to add immeasurably to his difficulties by refusing the well-grounded

request of Inchiquin for the Presidency of Munster.

In his wrath Inchiquin openly declared for the

Parliament in August. The necessity of coming to terms, and that speedily, with

the Confederates was more pressing than ever. But it was with a heavy heart and

little hope of success that Ormonde reopened negotiations in September, only to

break them off a week or two later owing to his inability to satisfy the

Catholic demands without sacrificing the Protestant interests. He asked to be

relieved of his post; but Charles knew his worth too well to accede to his

request. At the same time, however, recognizing that he was hardly the right

instrument to carry out his crooked policy, he yielded so far as to appoint the

Earl of Glamorgan, whom he had already designated to

command the Irish levies, to assist him in negotiating with the Catholics.

Various circumstances prevented Glamorgan from reaching Ireland before the beginning of

August. In the meantime fresh instructions reached Ormonde, authorizing him to

conclude a peace, and if necessary to concede the demand for the repeal of the

penal laws and the suspension of Poynings’ Act. Armed

with these new powers Ormonde reopened negotiations with the Confederates in

April, 1645, but only to find that, under the influence of the papal agent Scarampi and the clerical party, they had added to their

demands another for the retention of all such churches, chapels, and abbeys as

were then in their possession. Exasperated beyond measure at this new demand,

Charles declared that rather than consent to it he would withdraw his army from

Ireland, whatever hazard that kingdom might run by it.

|

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde (19 October 1610 – 21 July 1688) was an Anglo-Irish statesman and soldier. He was the second of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom. He was the friend of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who appointeed him commander of the Cavalier forces in Ireland. From 1641 to 1647, he lead the fighting against the Irish Catholic Confederation. From 1649 to 1650 he was top commander of the Royalist forces fighting against the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. In the 1650s he lived in exile in Europe with Charles II of England. Upon the restoration of Charles II to the British throne in 1660, Ormonde became a major figure in English and Irish politics, holding many high government offices- |

1645-6] Glamorgan’s intrigues discovered.

Affairs were in this critical position when Glamorgan arrived with a commission authorizing him to treat directly with the

Confederates, but couched in such curious terms and conferring on him such

extraordinary powers as raised strong, but apparently unfounded, doubts of its

genuineness. Finding on his arrival that the only hindrance to the conclusion

of the treaty was the newly raised question of the churches, and being

determined to secure at all costs the military support, which was to be the

price of the bargain, Glamorgan persuaded the

Confederate commissioners to embody their demand in a secret article, to which,

on the strength of his commission, he pledged the King’s conditional assent.

Matters being thus smoothed over in a way unknown to Ormonde, the public

treaty, as it must now be called, made rapid progress; and, the Assembly having

voted the 10,000 men, Glamorgan was delighted with

the success of his plan, when an accident put a sudden end to his hopes. On

October 17, in an attempt to recover Sligo, the Irish

were defeated with heavy loss by Sir Charles Coote.

Among those killed in the battle was the warlike Bishop of Tuam, Malachias Quaelly or Keely. In his pocket was found a copy of the Glamorgan Treaty. Its subsequent publication by the

Parliament caused a profound sensation, and did more than anything else to ruin

the King’s cause. But, even before his intrigues had come to light, Glamorgan had encountered a new and unexpected obstacle in

the person of Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, recently

appointed Legate by Pope Innocent X. Hitherto, under the restraining influence

of Innocent’s predecessor, Urban VIII, clerical influence had made itself little

felt in the counsels of the Confederates; but after the arrival of Rinuccini at Kilkenny on November

12, with a considerable supply of money and ammunition, the clerical party

began rapidly to gain the upper hand. Naturally, he had to be made acquainted

with the secret treaty, and, being from the first more intent on promoting the

papal than the royal cause, he made no secret of his dislike to the conditions

attached to it. However, at an interview with him on December 20 Glamorgan, by pledging the King’s conditional assent to the

appointment of a Catholic Viceroy and the admission of the Catholic Bishops to

sit in Parliament, succeeded in winning from him a reluctant consent to his

scheme.

Edward Somerset, 2nd Marquess of Worcester (1601-1667) In December, 1644, the King intimated to Ormond that the Earl of Glamorgan was coming to Ireland, to further the peace there. Glamorgan was probably selected for this mission as likely, being a zealous Catholic, to be specially acceptable to the Confederates. He crossed to Ireland the following July and, on landing, at once proceeded to Kilkenny, where he exhibited privately to the Council an authorisation from King Charles, given under his signet, to negotiate and conclude a treaty. This authorisation was most explicit. On August 25th (1645), he concluded with the Confederates a treaty on the following basis : Free and public exercise of the Catholic religion should be permitted throughout Ireland. All statutes against the Catholics should be repealed. All churches held by the Catholics since October 1641, should be retained by them. In return for all this, the Confederates should send 10,000 men to the King’s assistance. It was considered to concede too much to the Catholics there; he himself was a Catholic. In extricating himself from that position, he became a close ally of Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, and a potential replacement for James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde as royalist leader. His plans to bring Irish troops over to England were overtaken by events, and he left for France with George Leyburn. He was formally banished in 1649, but after four years in Paris returned to England in 1653. He was discovered, charged with high treason and sent to the Tower of London; he was treated leniently by the Council of State, and released on bail in 1654 |

Glad to have overcome this difficulty, Glamorgan hastened to Dublin to get things in readiness for transporting his men, when,

in consequence of his secret treaty having come to light, he was arrested at

the instance of Lord Digby. His arrest spread

consternation among the Confederates. None of them questioned his bona fides, and, in consequence of their

strong remonstrance, coupled with a threat of renewing the war, Ormonde

consented to release him on bail on January 21, 1646. Returning to Kilkenny, he endeavored by every means within his power to

bring the treaty to a conclusion; but, now that his disavowal by the King was

known, Rinuccini absolutely refused to abate one jot

of his demand for a confirmation of the concessions in the secret treaty before

he would agree to the conclusion of the peace, professing to have information

of a treaty in progress between the Pope and Sir Kenelm Digby on behalf of the Queen, containing more favorable

terms even than the secret treaty.

On the other hand, the majority of the Supreme Council were anxious to

conclude the peace on the basis of the agreement with Ormonde, leaving further

concessions, on the guarantee given by Glamorgan, to

Charles’ generosity. The time, they urged, had nearly passed when their

assistance could be of any service to him; and their own position was suffering

in consequence of the delay. Accordingly, after a long and stormy debate,

Articles of Peace, containing many valuable concessions, but leaving the

question of religion to the King’s decision, were signed on March 28. In

deference to the Nuncio it was agreed to postpone its proclamation till May 1,

in order to afford him time to obtain a copy of the pretended papal treaty, but

in the meantime to dispatch the long delayed assistance to the King with all

possible speed.

Unfortunately, the opportunity for this had passed away. By the end of

spring every available sea-port along the western coast of England was in the

hands of the Parliament. The collapse of the King’s cause in England and the

activity of the parliamentary party in Ireland, especially in Connaught,

brought forcibly home to the Confederates the necessity of immediate and united

action, if their own cause was to avoid a similar fate. Accordingly, nothing having

been heard of the papal treaty, and Ormonde refusing absolutely to sanction Glamorgan’s, the Supreme Council passed a resolution authorizing

the ratification and publication of the peace. The resolution had been carried

in face of the fiercest opposition of the Nuncio. Outvoted in the Council, Rinuccini, after entering a formal protest against the

resolution, summoned Owen O'Neill to his support. His messenger found that

general in the full flush of victory, having on June 5 almost annihilated the

Scottish army under Munro at Benburb. It was the only

great success that the Confederate arms had achieved, and its consequences

might have been even more important than they were, had O'Neill been allowed to

carry out his intention of attacking the Scots in their own quarters. Recalled

from his pursuit of them, he gave instant obedience to Rinuccini’s summons; while the Legate, relying on his support, convoked a meeting of the

clergy to Waterford, where on August 12 a resolution was passed condemning the

peace and forbidding its proclamation under pain of excommunication. The

Supreme Council was powerless to resist him; and, though the peace was

proclaimed at Dublin and Kilkenny, it was everywhere

else rejected. On September 18 Rinuccini entered Kilkenny in triumph, and, having caused his opponents to be

arrested, he appointed a new Council, consisting of his own immediate

followers, with himself as President, pending the election of a new General

Assembly. It was a most successful coup

d'état, and Rinuccini could with reason boast

that under his leadership the much despised clergy of Ireland had as it were in

the twinkling of an eye made themselves masters of the kingdom. His victory

ruined the national cause.

Giovanni Battista Rinuccini (1592-1653) Roman Catholic. He was a chamberlain to Pope Gregory XV, who made him the Archbishop of Fermo in Italy. He is best known for his time as Papal Nuncio to Ireland during the time of conflict known as the Irish Confederate Wars (1645-49) during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He was sent to Ireland in 1645 by Pope Innocent X, succeeding there Pierfrancesco Scarampi. Rinuccini embarked from La Rochelle and arrived in County Kerry with a retinue of twenty-six Italians, several Irish officers, and the Confederacy's secretary, Richard Bellings. At Kilkenny, the confederate capital, Rinuccini was received with great honours, asserting in his Latin declaration that the object of his mission was to sustain the King, but above all to help the Catholic people of Ireland in securing the free and public exercise of the Catholic religion, and the restoration of the churches and church property. Rinuccini sent ahead arms and ammunition. He arrived twelve days later with a further two thousand muskets and cartridge-belts, four thousand swords, four hundred brace of pistols, two thousand pike-heads, and twenty thousand pounds of gunpowder, fully-equipped soldiers and sailors and 150,658 livres tournois to finance the Irish Catholic war effort. These supplies gave him a huge input into the Confederate's internal politics, because the Nuncio doled out the money and arms for specific military projects, rather than handing it over to the Confederate government, or Supreme Council. Rinuccini hoped that by doing this he could influence the Confederate's strategic policy away from doing a deal with Charles I and the Royalists in the English Civil War and towards the foundation of an independent Catholic-ruled Ireland. In particular, Rinuccini wanted to ensure that Protestant churches and lands taken in the rebellion would remain in Catholic hands. This was consistent with what happened in Catholic-controlled areas during the Thirty Years' War and can be seen as part of the wider counter-reformation in Europe. The Nuncio also had unrealistic hopes of using Ireland as a base to re-establish Catholicism in England. However, apart from some military successes such as the battle of Benburb, the main result of Rinuccini's efforts was to aggravate the infighting between diffent factions within the Irish Confederates. |

1646-7] The Confederates

besiege Dublin.

For the moment, however, he was master of the situation, and he at once

turned his attention to the capture of Dublin. It was late in the year to begin

operations; but, having effected a reconciliation between Preston and O'Neill,

whose mutual jealousy had constantly weakened the Confederates, he determined

to make the attempt, and in November sat down before the city with 16,000 foot

and 1600 horse. Believing himself unable to offer any successful resistance,

Ormonde had already in September made overtures to hand over the city to the

Parliament; and, shortly after the siege had begun, commissioners arrived to

arrange the terms of its surrender. Influenced, however, by reports of fresh

dissensions in the camp of the Confederates and of their being prevented by the

bad weather from pursuing the siege with vigor, he plucked up courage to reject

the terms offered by Parliament. But his confidence was short-lived, and in

February, 1647, he renewed his offer to surrender on the terms formerly granted

him.

Several months elapsed before the negotiations were completed, and it

was not till July 28 that he formally handed over the sword of State to the

Commissioners appointed by Parliament to receive it. Aroused to a sense of

their danger, the Irish exerted themselves to recover the advantage of which their