CHAPTER XIV.

THE PEACE OF WESTPHALIA

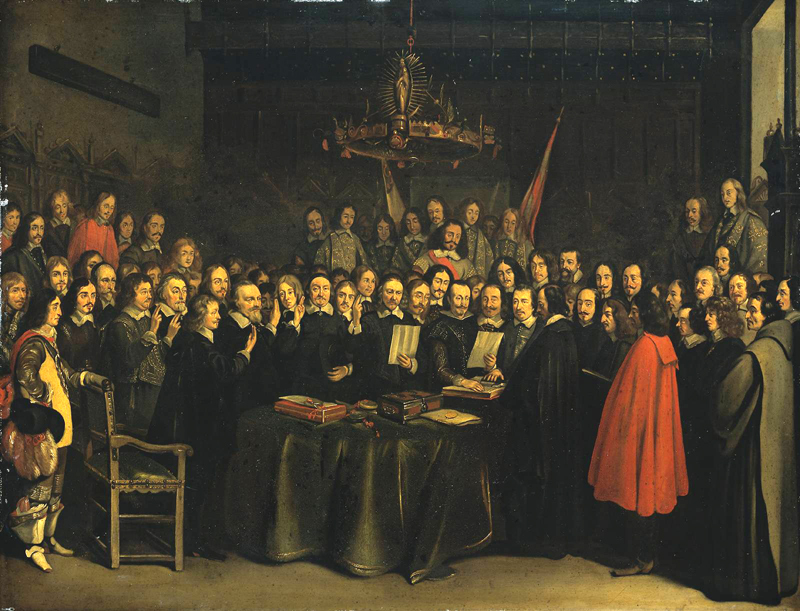

| Ratification of the Treaty of Munster (by Gerard Ter Borch) |

|

The Peace which, whatever its shortcomings, achieved

its purpose of putting an end to the Thirty Years’ War was not made at once;

and such had been the multitude and the complexity of the interests involved,

the frequency of the changes in the political situation brought about by the

shifting fortunes of the War, and the growth of mutual mistrust on all sides,

that the efforts of the peace-makers had seemed foredoomed to an endless

succession of failures. The evil, however, wrought its own remedy; and

advantage was taken of one among many variations in the course of a seemingly

interminable struggle to reestablish the European political fabric on bases

which in the main endured for nearly a century and a half. Change itself—the

transition from war to a peace which the nations could no longer see deferred—“reigned

over change”.

It has been seen in previous chapters how the project

of securing to the distracted Empire the blessings of peace had fared since

Wallenstein had in vain striven to be its arbiter, as his detested opponent

Gustavus Adolphus had been the arbiter of war. In May, 1635, the Elector John

George of Saxony, whose Imperialist sympathies had survived the Edict of

Restitution and the sack of Magdeburg, as well as the battles of Breitenfeld

and Lützen, succeeded at last in bringing to pass the compact known as the

Peace of Prague. Though it provided for the restoration of no Protestant Prince

dispossessed since 1630, and for the retention in Protestant hands of no

ecclesiastical property acquired since November, 1627; though it secured

neither the exercise of the Protestant religion in the dominions of any

Catholic Government, nor any rights whatever to the Calvinists—yet its

acceptance by the Saxon Elector, and the belief that the Swedish Power would

prove unable to maintain itself permanently in Germany, gradually drew over

nearly the whole of the Protestant Governments in the Empire to an acceptance

of its terms. But it could not liberate even John George’s own dominions from

hostile occupation; and the War was destined almost to double its length before

it came to an end.

Thus, the endeavors made in the last two years of

Ferdinand II’s reign, and in the early half of that of his successor, to bring

about a general peace, alike broke down. Towards the accomplishment of the end

in view two sovereigns in especial—the Pope and the King of Denmark—were

persistently eager to give their services as mediators; but each of them was

profoundly distrusted by one of the two belligerents between whom he proposed

to mediate. Pope Urban VIII, so early as the summer of 1635, had made proposals

through his uncle at Vienna for the assembling of a congress to discuss the

conditions of peace. In 1636 Ferdinand II and Philip IV, though perfectly well

acquainted with the French sympathies of the Pope, agreed to send ambassadors

to Cologne, where a congress was now actually gathering round the papal legate,

Cardinal Ginetti. But, though France had assented to

the Pope’s proposal, a pacific settlement would at this time have ill suited

the policy of Richelieu; and a pretext for hesitation was found in the refusal

of the Emperor and Spain to allow passes for the Swedish and the Dutch

ambassadors respectively. The Swedish Government were thus warranted in

declaring that they would have nothing to do with conferences held in a

Catholic city with the Pope as mediator; and, after a futile offer of mediation

by the Seigniory of Venice, the Cologne Congress came to an end without having

even brought about a truce. Urban VIII renewed his endeavors in 1638—this time

with the approval of Richelieu, whose purposes could not have been better

suited than by a prolonged cessation of arms on the basis of uti possidetis.

But Sweden demanded from France the payment of an annual subsidy of a million livres so long as

the truce concluded should endure; and the Pope's suggestion to transfer the

conference from Cologne to Rome was absolutely rejected at Vienna.

Before his death in February, 1637, Ferdinand II had

fallen back on the familiar conception that peace could only be obtained from

France by detaching Sweden from her. With this end in view, rather than that of

a general pacification, his agents had entered into negotiations at Hamburg

with the Swedish ambassador to the free city, the versatile and unscrupulous

John Adler Salvius, with whom we shall meet again at Osnabruck. He was playing

a double part, inasmuch as the Swedish Government was really intent upon the

renewal of its alliance with France, which in the following year (February,

1638) Salvius actually consummated. A conference which early in 1638 the feeble

Government of Charles I in the interests of his Palatine nephew sought, with

some support from France, to bring about at Brussels proved utterly abortive.

The Hamburg negotiations languidly continued, being on the Imperial side

chiefly conducted by an active diplomatist, Baron Kurtz (Count von Valley); but

the restored self-confidence of the Swedes would not tolerate the mediation of

Christian IV, whose services Ferdinand II had invited, and the Danish King was

entirely alienated from Sweden by her alliance with France.

Brandenburg and Luxemburg’s attempts at mediation

proved equally futile; and Count d'Avaux, the experienced diplomatist in charge

of the French interests at Hamburg, was again delaying rather than expediting

progress. Both he and Salvius, however, though far from any understanding

between themselves, kept up some kind of touch with the Imperial Councilor

Count von Lützow, who had arrived at Hamburg in 1640.

Endless discussions were carried on as to allowing

representation at the definitive Peace Congress, when it should be opened, to

the Estates of the Empire, and as to the form of the letters of safe-conduct to

be granted to those attending it. In the meantime the great engine for the

continuation of the general war—the Franco-Swedish treaty of alliance —was

renewed at Hamburg on January 30, 1641.

1640-5] The

Ratisbon Diet and the Frankfort Deputationstag.

Ferdinand III (13 July 1608 – 2 April 1657)

|

|

The Emperor Ferdinand III—who, like his father before

him, sought so long as it was possible to reach success by half-measures—had in

vain attempted a settlement by and for the Empire alone. His propositions at

the Diet of Ratisbon in 1640 aimed at expanding the Peace of Prague into a

settlement for the Empire at large, on the basis of an amnesty. There is no

reason for doubting the pacific intentions manifested by Ferdinand III, ever

since in 1635 he had in his capacity of probable successor approved Pope Urban’s proposal of a peace congress. But, though the

action of the son was not dominated in the same measure as that of the father

by religious considerations, Ferdinand III was at Ratisbon still unable to

realize under what conditions alone peace could be contemplated—not to say

concluded.

The indispensable preliminary condition of a pacific solution

acceptable throughout the Empire was that the proposed amnesty should be a

complete one. But even now Ferdinand III refused to include in it those

Protestant Estates who were still in alliance with foreign Powers, or to

entertain the notion that the Protestants as well as the Catholics should

return to their obligations to the Empire on a basis of rights of territorial

possession extending beyond that adopted in the Peace of Prague. He was unable

to perceive that the Protestant opposition in the Empire refused to be coerced

now as it had after the Smalcaldic War, and that even

a united Empire would no longer be able to control the European political

situation.

The Diet of Ratisbon, while steadily keeping in view

the assembling of a general peace congress, resolved that certain questions

concerning the internal affairs of the Empire, and more especially the Imperial

administration of justice, should be in the usual way referred to a Deputationstag.

Such a supplementary assembly actually met in 1642 at Frankfort, where for some

three years it carried on its inanimate proceedings. But, though the Emperor

had intended to charge it with so much of the business of the peace negotiations

as concerned the Empire only, and thus to keep the several German Governments

out of the general peace congress, he had, as we shall see, to abandon this

policy; and in April, 1645, the Frankfort Deputationstag broke up.

Some years before this, the scheme of a General

Congress had at last matured. On the one hand, it had come to be recognized,

even at Vienna, that, when the terms of a final pacific settlement came to be

actually discussed, the real difficulties to be overcome would lie in the

conditions of the “satisfaction” to be granted to France and to Sweden

respectively at the cost of the Empire. On the other hand, a serious obstacle

would arise if the Emperor, continuing to regard his interests as identical

with those of Spain, were to insist on the conclusion of peace between himself

and his adversaries being made dependent on a simultaneous settlement between

Spain and France; although there could be no reason against advantage being

taken of the opportunity for negotiating a separate peace between Spain and the

United Provinces (still technically included in the Empire), which to Spain was

becoming more and more necessary.

Though the peace negotiations at Hamburg had not

entirely collapsed like those at Cologne, it had at length become obvious that

business would proceed more rapidly, and a successful issue seem less remote,

if the separate negotiations with France and Sweden respectively were carried

on in two localities between which communication was easy. Hence the felicitous

proposal, brought forward by d'Avaux in the latter part of 1641, that for

Cologne and Hamburg should be substituted Munster and Osnabruck, two

Westphalian towns which are not more than thirty miles distant from each other.

The proposal was after some hesitation accepted by Sweden, and then by the

Emperor, upon whom it was urged by the Ratisbon Diet. Lützow, d'Avaux, and

Salvius hereupon succeeded in negotiating at Hamburg the Preliminary Treaty,

which was concluded on December 25,1641, and is to be regarded as the first step

actually taken towards the final Peace. It provided for the opening on March

25, 1642, of peace conferences at Munster and Osnabruck; the two assemblies to

be regarded as forming a single congress, and both towns to be declared neutral

territory. Inasmuch as the Peace was technically to be concluded between the

Emperor and his allies on the one hand, and the Kings of France and Sweden and

their allies on the other, safe-conducts were to be made out on behalf of the

Emperor to the allies or adherents of France or Sweden respectively. With

France the Emperor would treat at Munster under the mediation of the Pope and

the Seigniory of Venice, with Sweden at Osnabruck under that of Christian IV of

Denmark. The Preliminary Treaty was ratified by Louis XIII on February 26,

1642; but the Emperor delayed his ratification till July 22; nor were the

difficulties besetting the assembling of the Congress even then at an end.

Before the Imperial ratification Lützow had made one more futile attempt to

detach the Swedish from the French Government; and about the same time

Maximilian of Bavaria, utterly skeptical as to the assembling of a general

peace congress, was seeking to induce the Electors of Cologne and Mainz to join

with him in a separate negotiation with France—a scheme which he sought to

revive after Mazarin had succeeded Richelieu in the direction of the foreign

policy of France (December, 1642). In the end, however, with the aid of the

impression created by Torstensson’s victory at Breitenfeld, all obstacles were

removed; the Preliminary Treaty was accepted by Spain, and the Emperor agreed

to furnish letters of safe-conduct even to those members of the Heilbronn

Alliance who had not yet become reconciled to him. The date of the meeting of

the Congress at Munster and Osnabruck was fixed for July 11, 1643.

1643-8] Opening

of the Congress at Münster and Osnabruck

But though the Imperial plenipotentiaries made their

appearance in both places with praiseworthy punctuality, such was not the case

with most of their colleagues; and the French ambassadors did not reach Münster

till April, 1644, having on their way concluded an offensive alliance with the

States General against Spain. This alliance, however, failed to prevent the

ultimate conclusion of a separate peace between these two Powers; just as the

Emperor's promise that he would not make peace with France till Spain should

also have concluded peace with that Power was to be ignored in the settlement

between France and himself at Munster. The course of the negotiations between

Spain and the United Provinces, and their result, will be related in a later

chapter; in the Peace of Westphalia proper these Powers were included only as

allies of two of the belligerents respectively, the Emperor and France; the “Burgundian

Circle” of the Empire being treated as in the hands of Spain.

During the year 1644 the ambassadors continued to

arrive, and the beginnings of a great international concourse stirred the

quaint cloisters of the Rathhaus in the ancient cathedral city of Münster, and

the more scattered streets and lanes of Osnabruck. In accordance with the

tendencies of an age delivered over to formalities in Church and State, in

council and in camp, the beginnings of the discussions between the

plenipotentiaries were occupied with questions of precedence and procedure,

before they so much as approached the problems which the issue of these

discussions was to decide. The Congress did not actually get to work till the

spring or early summer of 1645, by which time all the immediate (and a few of

the mediate) Estates of the Empire had received their summons to attend, so

that 26 of the votes at the Diet were represented at Munster, and 40 at

Osnabruck. On June 1 the French and the Swedish plenipotentiaries at the two

places of meeting brought forward their propositions of peace—the former in

their own language, the Swedes in Latin. The general progress of business at

the Congress may be summed up as follows. The propositions of the two Crowns

were received, answered, debated, and settled during a period extending from

the above-mentioned date (June 1, 1645) to that of the signature of the Treaty

of Peace (October 24,1648); but the discussions of these propositions by the

Estates of the Empire lasted only from October, 1645, to April, 1646. On the

other hand, the deliberations on the religious grievances brought forward on

one and the other side occupied the greater part of the period during which the

Congress sat, from February, 1646, to March, 1648. As some of the chief

plenipotentiaries at the Congress necessarily exercised a controlling influence

upon both the main divisions of its labors, it may be convenient here to

enumerate the most notable among the members of a bipartite assembly of politicians,

unprecedented alike in the numbers of its members, and in the variety of the

interests represented by them.

To the Emperor’s chief plenipotentiary, Count

Maximilian von Trautmansdorff, the work which the Congress actually achieved

was preeminently indebted. His firm and self-sacrificing resolve to carry to a

successful issue the task which proved to be the final task of his life, rather

than any great subtlety in dealing with affairs or irresistible personal charm,

enabled him to compass his end. Like Eggenberg, to whose group or party in the

Court and Government at Vienna Trautmansdorff had attached himself, he was

early in life converted from Protestantism. After supporting Wallenstein he had

at last counseled the arrest of the Dictator; but he continued to cherish some

of the great would-be pacificator's designs. After taking over from Eggenberg

the direction of Ferdinand II’s counsels, he had helped to bring about the

Peace of Prague; and under Ferdinand III, whose entire confidence he commanded,

his consistent efforts for peace were as unacceptable to the Spanish party as

his loyalty to the House of Austria was vexatious to Bavaria.

Trautmansdorff did not make his appearance at Münster

before December, 1645; but from this date onwards till his withdrawal in July,

1647, more than a year before the signing of the Peace, he was not only, in

Oxenstierna’s phrase, the soul of the Imperial embassy, but succeeded in

contributing more than any of his fellow-plenipotentiaries to the work of

peace. His success was due to a remarkable flexibility in the conduct of

business; but he was always careful of the dynastic interests of the House of

Austria, and cannot be acquitted of having sacrificed to these the security of

the Empire at large on its western border. His efforts were supported at Münster

by Isaac Volmar, an astute lawyer and experienced

official, and by the personal graces of Count, afterwards Prince, John Lewis of

Nassau-Hademar; and at Osnabruck by a pair of

ministers who in much the same way balanced each other.

1645-8] German,

Spanish, and Dutch plenipotentiaries

Each of the Electors—Spiritual and Temporal—was

individually represented at the Congress; but the Bishop of Osnabruck (Count

Francis William von Wartenberg, also Bishop of Bremen and Verden, and

afterwards Bishop of Ratisbon and Cardinal), who had received powers from the

Elector of Cologne and certain other ecclesiastical dignitaries, was finally

named representative of the entire Electoral College. An illegitimate scion of

the Bavarian House, and a pupil of the Jesuits, he had rigorously carried out

in his diocese the Edict of Restitution, and was in the Congress the chosen

champion of German Catholic interests—for the policy of the Bavarian Elector

was distracted between Catholic sympathies and a growing desire to lean upon France.

Among the plenipotentiaries of the Protestant Electors and Princes on the other

hand, the foremost was Count John von Sayn-Wittgenstein,

the trusted ambassador of Frederick William of Brandenburg. He had served in

arms under Landgrave William of Hesse-Cassel, if not under Gustavus Adolphus

himself, and had been a member of the consilium formatum of the Heilbronn Alliance. Familiar with

Swedish as well as with French politics, he was able to promote with skill and

vigor the interests of Brandenburg, which may be said already at this Congress

to have borne itself as the leading Protestant German State. Many of the other

Estates of the Empire were represented by diplomatists of proved experience,

some of whom were also celebrated publicists, and, as in the case of the

Benedictine Adam Adami, afterwards Bishop Suffragan of Hildesheim and the historian of the Congress,

exercised a powerful personal influence upon its deliberations. In the

discussions among the German Estates Adami and the

Bishop of Osnabruck frequently commanded a majority of the entire Catholic

vote; more moderate members of the party being as a rule found at Osnabruck,

and the more extreme at Münster, while Jesuit agents eagerly watched and

reported on their action. Among the plenipotentiaries of the Protestant Princes

mention should be made of the learned Brunswicker Jacob Lampadius, and the Württemberger John Conrad Varnbüler, a worthy pupil of Gustavus Adolphus’ faithful

counselor Jacob Loffler. The chief advocate of the interests of the Swiss

Confederation was John Rudolf Wetstein, Burgomaster

of Basel, so influential a personage that he was known by the sobriquet of “King

of the Swiss”.

The Emperor’s ally the King of Spain had, in addition

to a pompous grandee, Gasparo de Bracamonte (afterwards Viceroy of Naples), and a learned ecclesiastic, Joseph de Bergaigne (Bishop of Hertogenbosch, and from 1645

Archbishop of Cambrai), commissioned two capable

diplomatists, Count Guzman of Peñaranda and a famous

man of letters, Antoine Brun (Bruins). To their

labors was mainly due the actual conclusion of peace between Spain and the

United Provinces, without the intervention of France. Each of the United

Provinces was individually represented at Münster; Holland and Zeeland

respectively sending Adrian Pauw, Lord of Heemsteede, and John van Knuyt.

The latter of these, as an adherent of the Prince of Orange, was at the outset

supposed to have no desire for peace; but Frederick Henry modified his views

before his death in 1647, and the States General, under the influence of the

bold diplomacy of Francisco de Sousa, the Portuguese ambassador at the Hague,

took up a stand which forced Spain into a settlement. At Münster the diplomatic

agents of the newly re-established kingdom of Portugal, and those of the

Catalan insurgents, appeared under the wing of the French peace embassy.

The French plenipotentiaries at Münster were Abel Servien, Marquis de Sable, and Claude de Mesmes, Count d'Avaux. The share taken in the Hamburg

negotiations by d'Avaux, who had succeeded Charnace as the chief agent of the policy of Richelieu in the Empire, has been already

noted. He was a strong Catholic, and as such enjoyed the particular goodwill of

Maximilian of Bavaria. Some jealousy prevailed between him and his colleague,

who, though his inferior in knowledge of affairs, surpassed him in certain

other diplomatic qualities and, since Mazarin had taken the helm, was better

supported from home. The inconveniences caused by this estrangement, together

with the wish to give éclat to the French embassy, induced the Queen Regent in

1645 to furnish it with a figure-head in the person of Henry of Orleans, Duke

of Longueville; and in 1647 Servien was detached on a special mission to the Hague. But Mazarin kept up an

understanding with him, and on his return to Münster the Duke quitted the city

before the actual conclusion of the Peace. D'Avaux himself was recalled just before

the signing of the Treaty.

The Swedish plenipotentiaries at Osnabruck were also,

though in a less marked degree than their French colleagues at Münster, on

unfriendly terms with one another. Count John Oxenstierna, the eldest son of

the Chancellor, had served in the German War under his relative Field-Marshal

Horn, and had gained some knowledge of the chief European States by travel. But

he was not his father's equal in intelligence, or able to fall into line with

the statecraft of John Adler Salvius, whose experience of affairs extended back

to the Prussian War of Gustavus Adolphus, and who was favored by the young Queen

Christina, jealous of the Oxenstierna influence ever since, in December, 1644,

she had taken the government into her own hands.

It remains to note that, of the Mediating Powers, Pope

Urban VIII, and after his death in 1644 his successor, Innocent X, was

represented in the Peace negotiations by Fabio Chigi,

formerly Papal Nuncio at Cologne and afterwards Cardinal and Secretary of State

under Pope Innocent X, whom he in his turn succeeded as Pope Alexander VIII.

With Chigi, who was perhaps better qualified for his

labors at Munster than for the greater task that awaited him, was appointed Alvisi Contarini, a member of one

of the most illustrious of Venetian families, whose diplomatic services to the

Republic had already extended over nearly two decades. On the whole they acted

in harmony with one another; and the falling off of the Venetian's French

sympathies synchronized with the change in the policy of the Vatican on the

death of Urban. The ambassadors of King Christian IV, who acted as mediator at Osnabruck,

Justus Hog and Gregers Krabbe,

both of them members of the Rigsraad, had been instructed by their sovereign to indulge

in a lavish expenditure; but the outbreak of hostilities between Denmark and

Sweden led to their departure from Osnabruck in December, 1643; and the

negotiations there were thenceforth carried on without a mediator. No Christian

Power was unrepresented at either Münster or Osnabruck except the Kings of

England and Poland and the Grand Duke of Muscovy—and the former two were

included in the Treaty as allies both of the Emperor and of Sweden, the

Muscovite as the ally of Sweden only. The Porte took no part in the Congress.

It should be added that the extravagance displayed there on all sides was

largely dictated by a desire to show that the sacrifices of the war had not

exhausted the resources of the various belligerents: the entry of d'Avaux into

Münster lasted for a whole hour, and at Osnabruck Oxenstierna never showed

himself in public except in quasi-royal state. Much money was spent on polite

entertainments, and more on drinking-bouts. As to the expenditure for purposes

of corruption, neither its occasions nor its amount admit of definite

statement.

1645-8] The “satisfaction”

of Sweden.

Gustav II Adolf of Sweden (1594 –1632) |

|

As already observed, the question of the success or

failure of the negotiations at Münster and Osnabruck really turned on the “satisfaction”

of the Swedish and of the French Crown. Though, in his first answer to the

original Swedish peace propositions the Emperor had stated that he was

unprepared to proffer any satisfaction to either Power, inasmuch as both rather

owed satisfaction to him, he declared himself willing to assent to a money

payment by the Estates of the Empire to Sweden. In reply, that Power appealed

to the fact that Gustavus Adolphus had been induced against his own wish to

enter into the war, and that the enormous and irreparable sacrifices entailed

by it upon Sweden included that of the King's own precious life. When at last

the Swedish plenipotentiaries were brought to formulate their demands, these

included the permanent cession to the Swedish Crown of Silesia, the whole of

Pomerania, with Mecklenburg, Wismar, and the island of Poel,

the archbishopric of Bremen, the bishopric of Verden, and certain other

ecclesiastical lands, with a compensation to the officers and soldiers of the

Swedish army.

The territories forming part of the Empire Sweden did

not desire to sever from it, but to hold as Imperial fiefs, the Swedish

sovereign thus becoming an Estate of the Empire and entering into the

obligations towards it implied by this relation. But although, as has been

seen, the Swedes at the end of the War still held a considerable number of

places in the Empire, including part of Bohemia, they obviously had no

intention of insisting upon the demand of Silesia. Pomerania, on the other

hand, they had long resolved to annex, with or without the consent of

Brandenburg. The Elector George William had steadily refused to yield on this

head to Gustavus Adolphus, when at the height of his power; but by his

acceptance of the Peace of Prague the Elector had finally gone over to the side

of the Emperor; so that when by the death in 1637 of Bogislav XIV, the last native Duke of Pomerania, the House of Brandenburg acquired an

indisputable right to the entire Duchy, Sweden had a sufficient pretext for

occupying it. Although Imperial troops had by repeated incursions into

Pomerania contested this occupation, the Swedes had not given way, even after

the accession in 1640 of Frederick William as Elector. The Pomeranian Estates

were on the whole (notwithstanding some Lutheran qualms) in favor of the

Brandenburg claim, while the Swedish pretensions were founded simply on the de facto occupation. Thus, it was

ultimately agreed that the old division between Vor- and Hinterpommern (Western and

Eastern Pomerania) should be revived; and that, while the latter passed to

Brandenburg, the former, with the island of Rügen and

the town of Stettin, and certain places on the eastern side of the Frische Haff, should be allotted

as a distinct duchy to Sweden. This arrangement necessitated a compensation to

Brandenburg, while the further cession to Sweden of the port of Wismar and the

island of Poel made it requisite to find some

equivalent for Mecklenburg. Sweden also acquired, as secular duchies held under

the Empire, the archbishopric of Bremen, of which she had at the outbreak of

hostilities with Denmark in 1643 deprived its Danish Occupant, Prince

Frederick, and the adjoining bishopric of Verden, from which she had expelled

the pluralist Bishop of Osnabruck. This was the earliest in the series of secularizations

effected in the course of these negotiations; no expedient commended itself so

readily for use, and none could have more plainly demonstrated the failure of

the whole policy of reaction and restitution which had begun and protracted the

War. Sweden would henceforth have seat and vote at the Imperial Diet, and be a

member of three of the Circles of the Empire; and in Pomeranian Greifswalde she would, as was specially provided, possess a

German University of her own. It should be noted that, by a special provision

of the Treaty of Osnabruck, all Swedish garrisons were withdrawn from the Mark

Brandenburg.

Finally, a settlement was made as to the claims

preferred by the Swedish Crown on behalf of the officers and soldiers in its

service during the War. Though the Imperial plenipotentiaries had maintained

that every Power ought to deal with its own soldiery, Queen Christina insisted

most strongly on the “satisfaction of her militia”; and, after a demand of

twenty million dollars had at first been put forward, a contribution of five

millions for this purpose was imposed upon seven of the Circles of the Empire.

1645-8] The “satisfaction”

of France. Alsace

France, like Sweden, was slow in formulating her terms

of “satisfaction”. When they were at last presented, the recognition

of her sovereignty over the three bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun, of

which she had been in actual possession for all but a century, was granted

without much ado. The sovereignty of the King of France over Pinerolo was likewise recognized, the provisions of the

Treaty of Cherasco between France and Savoy (1631)

remaining practically unaltered; but Savoy retained its existing territorial

rights and limits. Duke Charles of Lorraine was left out of the Congress, and

out of the Treaty.

The claims of France upon Alsace were not so easily

settled. The French Government had repeatedly declared that it made war upon

the House of Austria, and not upon the Empire; and it was clear from the outset

that the House of Austria would have to defray the main cost of the French “satisfaction”.

This view of the case, which commended itself to Bavaria and the Spiritual

Electors hardly less than to the Protestant Princes, throughout governed the

diplomatic action of France in this matter; and she began by simply demanding

the cession to her of the Austrian possessions and rights in Alsace. But when

the French Government and its agents, with Servien at

their head, entered into these far-reaching negotiations, they were quite

uninformed as to the actual extent and character of these rights, and as to the

relations to the Empire of the component parts of Alsace. Moreover, unhappily

for the integrity of that Empire and for the future peace of Europe, it did not

suit the purposes of the House of Austria—desirous of averting any French

designs upon other territories in its possession—to dispel the ignorance of the

French negotiators.

As a matter of fact, although so late as the middle of

the seventeenth century Alsace had lost neither its unity of race, nor a

certain cohesion of life and culture, its two historic divisions of Upper and

Lower (southern and northern) Alsace had followed quite distinct lines of

political growth. Of the two landgravates into which

the ancient duchy had been administratively divided, that of Upper Alsace had,

from the days of its landgrave the great Emperor Rudolf I, fallen more and more

under the control of the House of Habsburg, to which nearly four-fifths of the

land were now feudally subject. In Lower Alsace, on the other hand, the

Austrian rights were virtually restricted to those of the Landvogt,

who since the reign of Ferdinand I exercised a certain administrative authority

in a district comprising, besides some forty villages in Lower Alsace, the

so-called “ten free Imperial towns of Alsace” in both its divisions (Hagenau, Colmar, Schlettstadt,

etc.). The nobility of Lower Alsace retained their independence, and its Diets

their activity, while the dignity of landgrave had here become

merely titular (with a domain or two attached to it) and, so far back as the

fourteenth century, had been acquired by purchase by the Bishop of Strasbourg.

The see had no other formal connection with Lower Alsace; nor was there any tie

of the kind between the latter and the free city of Strasbourg, which, like the see, was immediate to the Empire.

Yet, when in 1645 Mazarin instructed the French

plenipotentiaries to demand, in addition to the fortresses of Breisach and Philippsburg, “Upper

and Lower Alsace” (the Sundgau being treated as part

of the former), there can be no doubt that he and they supposed the whole of

Alsace and its Estates to be in one way or another subject to the House of

Austria. Being, however, apprised by their Bavarian friends that the case was

not quite so simple, they thought it expedient to raise their terms by throwing

in a demand for the whole Breisgau (on the right bank

of the Rhine), which by November, 1645, Mazarin reduced to a claim on the

fortress of Breisach only.

In these terms the Emperor acquiesced, secretly

instructing Trautmansdorff to this effect in March, 1646; and though some

further haggling followed on both sides, a settlement on the subject was now to

all intents and purposes assured. The Austrian proposals brought forward in

April, and substantially agreed to in the Preliminary Treaty signed in

September following, were embodied in the final instrument of peace. Breisach—to which Bernard of Weimar had so tenaciously

clung—was made over to France. But as to the cession of the “landgravate of Upper and Lower Alsace”, or of the “landgravate of both Alsaces” (for

both terms had been in use) which, together with the Landvogtei over the ten towns and

their dependencies, was to pass in full sovereignty to France, certain ominous

obscurities remained. In the first place, while the King of France undertook to

respect the liberties and the immediacy to the Empire, not only of the Bishops

of Strasbourg and Basel, but also of all the other immediate Estates in both

Upper and Lower Alsace, including the ten free towns, he did so on condition (Ita tamen) that

the rights of his sovereignty should not suffer from this reservation. The

clause gave rise to much alarm at the time, and was afterwards deliberately

misinterpreted; but its chief purpose was, beyond all reasonable doubt, simply

to secure to the Crown of France the measure of rights which the House of

Austria had formerly possessed in Alsace. In the second place, the expression landgraviatus inferioris Alsacae implied a measure of rights which the House of

Austria could not transfer, because, as has been seen, it had never possessed

them. No “landgravate of Alsace”—a term first

imported by Austria into the negotiations—had ever existed; and the “landgravate of Lower Elsass”

implied a title to which Austria had not a shadow of a claim. Thus in Lower Alsace

Austria had nothing to surrender beyond the Hagenau Landvogtei, which

in no wise involved the surrender of the ten free Imperial towns, though these

were in certain respects subject to her authority. For the misleading

phraseology, by which, as conferring upon France rights in Lower Alsace that

Austria had never possessed, Louis XIV afterwards sought to justify his

notorious “Reunions”, Austria, and not France, was in the first instance

responsible.

1645-8] Alsace

settlement. General amnesty. Brandenburg.

The attempts of the Estates of the Empire at Minister

and Osnabruck, and of the Estates in Alsace itself, to get rid of the ominous Ita tamen clause

were skillfully eluded by Servien, who professed

himself quite ready to accept the alternative suggestion that France should

hold both Upper and Lower Alsace as fiefs of the Empire. But the Emperor, who

had no desire for such a vassal, would not hear of this solution. Nothing was

gained by the agitation except that the city of Strasbourg was expressly named

among the Estates to be left untouched in their liberties, though Servien declared that there had never been any intention of

including it in the French “satisfaction”. Neither with regard to Alsace at

large, nor most certainly with regard to Strasbourg, is there any evidence that

either Servien or the French Government had at this

time deliberately formed any ulterior design.

An article of the Treaty obliged the King of France to

maintain Catholic worship in Alsace wherever it had been carried on under the

Austrian Government, and to restore its exercise where it had been interrupted

in the course of the War. A compensation of three million livres was granted by France to

Archduke Ferdinand Charles, who had held the position of Governor of the “Anterior”

Austrian possessions; and a part of his debts was taken over by her. Though

France had not insisted on the cession of Philippsburg,

she was allowed the right of maintaining a garrison in the fortress, while the

town was left to the Bishop of Speier.

The Peace provided for a general and unlimited amnesty

in the Empire which was to go back to the Bohemian troubles—i.e. to the year 1618—and to extend to

all Princes and other Estates, immediate or mediate, and their subjects,

possessions, and public and private rights. But the particular changes and

settlements in the Empire expressly mentioned in the Treaties were held to

override any general provision; and on this head the exceptions were in part of

very great significance.

Foremost among the Princes of the Empire whose

interests had been impaired by the Swedish “satisfaction” stood the Elector of

Brandenburg. Regarding the sees of Brandenburg and Havelberg, together with that of Camin (a dependency of Eastern Pomerania) as permanently appropriated by his House,

he now demanded certain Silesian principalities, without any serious

expectation of inducing the House of Austria to hand them over to him, together

with the secularization, in favor of his dynasty, of the archbishopric of

Magdeburg, and the bishoprics of Halberstadt,

Hildesheim, Osnabruck, and Minden. His vigorous diplomacy actually secured to

him the first and the last named of these bishoprics, and the archbishopric of

Magdeburg, as hereditary possessions. Magdeburg was, however, not to pass to

his House as an hereditary duchy until the determination of Prince Augustus of

Saxony’s life tenure. The much-vexed administrator Prince Christian William was

granted an increase of the pecuniary consideration allowed to him in the Peace

of Prague.

The Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, in compensation for

the transfer of the lucrative port of Wismar, obtained possession of the sees of Schwerin and Ratzeburg;

certain actual or contingent equivalents being granted to his kinsman of the Güstrow

branch.

Brunswick-Luneburg.—Hesse-Cassel. [1645-8

The interests of another north-German House had been

prejudiced by these arrangements and the absorption by Sweden of the archbishopric

of Bremen. This was the House of Brunswick-Luneburg, which under Duke George,

up to his death in 1641, had played so prominent a part in the latter part of

the War. But the Brunswick-Luneburg Dukes, who had in 1642 at Goslar

prematurely concluded a separate peace in their own interests, were now obliged

to give up Hildesheim to its Catholic Bishop, the Elector of Cologne, and to

see Minden transferred to Brandenburg. Of the three sees on which the Princes

of the ambitious House of Brunswick had set their hopes, only a moiety of one

was assigned to them. For it was settled that at Osnabruck the present Catholic

Bishop should be succeeded by the Brunswick-Luneburg Duke Ernest Augustus, and

that after him the see should be alternately held by a Catholic and a

Protestant, in the latter case preferentially by a Brunswick-Luneburg Prince.

By another abnormal arrangement the Bishop, Chapter, and Estates of Osnabruck

were made liable for the payment of 80,000 dollars to the former occupant of

the territory, Count Gustaf Gustafsson,

of Vasaborg, an illegitimate son of the great King.

On the other hand, a still outstanding claim of the heirs of Tilly upon the

principality of Calenburg (Hanover) was now quashed.

The Dowager Landgravine Amalia Elizabeth of Hesse-Cassel had in the face of difficulties innumerable

maintained so close a connection with both the Swedish and the French

Government that their military commanders and diplomatists alike never lost

sight of her interests and pretensions. Special mention accordingly was made of

them in the first peace propositions of both Powers. Her claims were

judiciously spread over a large and varied extent of territory; but in the end

Hesse-Cassel acquired the secularized Prince-abbacy of Hersfeld,

which had long been under its control, together with other lands and the large

sum of 600,000 dollars for the payment of its soldiery, to be contributed by

divers spiritual potentates. The compact between Cassel and Darmstadt securing

to the former part of the long-disputed Marburg succession was also confirmed

in the Peace; so that the “great Landgravine”—a Princess whose extraordinary

sagacity and determination deserve enduring remembrance—was now entitled to

sing her Nunc Dimittis. She

died in 1651.

The Peace of Westphalia failed to effect any final

settlement of the Jülich-Cleves-Berg question, which had so nearly antedated by

a decade the outbreak of the Great War. A pious hope was expressed that the “interessati”, who, besides the “possessing” Princes, were

Brandenburg and Neuburg, the Elector of Saxony and

the Duke of Zweibrücken, would soon come to terms; but this hope was not

fulfilled till 1666, when, by the Treaty of Cleves, Brandenburg was awarded the

permanent possession of Cleves, Mark, and Ravensburg,

and Neuburg of Jülich and Berg—a settlement which

lasted till the expiration of the Neuburg line in

1742. The Donauworth difficulty, too—another of the

causes of the Thirty Years’ War—was left over for settlement by the next Diet;

and Bavaria remained in possession, compensating the Swabian Circle for the

loss of the town’s contributions. A third and more important question, which

during the course of the War had only gradually fallen into the background,

once more became prominent in the peace negotiations and had finally to be

settled by a compromise. The voice of England, the one Western Power

unrepresented in these negotiations, could no longer be raised on behalf of

Charles Lewis, the eldest son of the late Elector Frederick; and the States

General could hardly be expected to intervene actively on behalf of a family of

which they had long grown weary. On the other hand, Bavaria would leave no

stone unturned in order to retain possession of the Electoral dignity and of

the Upper Palatinate. If Maximilian had to surrender this acquisition, he would

at once claim from Ferdinand III his father's pledge of Upper Austria and a debt

of thirteen million dollars; and, if Maximilian lost his Electorship, there

would be an end of the Catholic majority among the Temporal Electors. It was

accordingly at last agreed that the Upper Palatinate, and the fifth electorate

which had been transferred to Maximilian in 1623, should remain with the

Bavarian branch of the House of Wittelsbach, while

the Lower Palatinate, with a newly-created eighth electorate, was assigned to

Charles Lewis and his descendants. As the new Elector Palatine would

participate in the general amnesty, the Emperor undertook to avert so far as he

could any opposition in the Lower Palatinate to the restoration of Charles

Lewis, and even promised him a certain measure of pecuniary relief and support.

Unfortunately it neither supplied his economic needs on his return to the

desolate remnant of his patrimony, nor brought about a reconciliation between

him and his mother, the ex-Queen of Bohemia, who after her Odyssey of woes was

never to see Heidelberg again.

Both the Baden-Durlach line,

which had been deprived of its territories after the battle of Wimpfen (1622) and the House of Wurttemberg, of whose

domains Ferdinand II had in his last years distributed a large part among his

ministers and commanders, had been excluded from the amnesty granted at the

Peace of Prague and were now reinstated. This was mainly the work of Varnbüler, who thus signally contributed to the

preservation of Protestantism in south-western Germany. Several other Estates

of the Empire, which had likewise been excluded from the Prague amnesty, and

others which had not been so excluded, endeavored to secure similar recoveries;

and in the end a stop had to be put upon these transactions, which threatened

indefinitely to postpone the conclusion of peace. The Elector of Trier, thanks

to French support, re-entered into all the rights and possessions which he had

forfeited, and his soldiery replaced the Imperialist garrisons in his

fortresses of Ehrenbreitstein and Hammerstein.

While the loose connection between the United

Provinces and the Empire was allowed to lapse in silence in view of the

recognition by Spain of the independence of what still formed part of the

Burgundian Circle, the independence of the Helvetic Confederation of the Thirteen Cantons was explicitly recognized in the Treaties

of both Osnabruck and Münster.

Religious

grievances. [1648

It remains to summaries the efforts made in the Peace

of Westphalia to deal with the religious and political difficulties, for the

most part so repeatedly and persistently brought forward as “grievances” at the

Diet and other meetings of Estates of the Empire, that had long distracted and

disturbed its life, and had materially contributed to bring about the War. The

gravest of these difficulties dated back in their origin to the Reformation;

nor could any settlement of them be reached unless they were regarded as

radical and treated accordingly. The peace propositions of the Swedish

plenipotentiaries demanded that all mutual grievances between the Catholic and

Protestant Estates should be entirely uprooted (funditus exstirpentur). As representing a

Catholic Power, the French plenipotentiaries were precluded from professing the

same purpose; and thus it was only at Osnabruck that the religious grievances

were discussed, and the principle of their being ultimately met by a reunion of

the religions was once more asserted. The endeavors of the Imperial plenipotentiaries

to refer the religious grievances to the Diet broke down, and to the exertions

of Sweden, whose services to the preservation of Protestantism did not come to

an end with the career of Gustavus Adolphus, are to be ascribed such results as

were on this head reached in the Peace of Westphalia.

The Treaty of Passau (1552) and the Religious Peace of

Augsburg (1555) were acknowledged as fundamental laws of the Empire, but were

here broadened in their application by the important provision, that among the “adherents

of the Augsburg Confession” should be held to be included those who proposed

the “Reformed” (Calvinist) form of faith. The Elector of Saxony, consistent to

the last, protested against this article. So far, however, was it from implying

any general religious tolerance, that the same Treaty of Osnabruck expressly

directed that no other religion except those expressly mentioned should be

allowed in the Empire—a declaration not of course intended to prevent any

particular Government from granting such protection as it might think fit to

individual adherents of other forms of religion.

Sweden had originally proposed that, in view of the

manifold grievances on both the Catholic and the Protestant side, the state of

possession which had existed in the year 1618 should be restored and made

perpetual in the case of ecclesiastical foundations and property of all kinds,

and in that of all other disputed matters admitting of being so regulated. This

proposal represented so enormous an advance upon the Prague settlement, which

had fixed the year 1627 for the same purpose and allowed a period of possession

from that date onwards of not more than forty years, that, after prolonged

discussions and determined Catholic resistance, the date of January 1, 1624,

was, on the motion of Electoral Saxony, definitively adopted. It was favorable

to the Protestants, as entirely excluding the operations of the Edict of

Restitution, and even some changes effected by Tilly; on the other hand, a

large number of immediate Church foundations were thus left to the Catholics.

Exclusively, then, of those ecclesiastical

foundations — chiefly secularized sees— specific dispositions as to which formed

part of the satisfactions or compensations—all immediate foundations and

estates, whether archbishoprics, bishoprics, abbacies, convents or other, were

to remain in the undisturbed possession of whichever of the religions had held

them on January 1,1624, until by God’s grace the religious disunion should have

an end. If the occupant of such a foundation changed his religion, his

occupancy would ipso facto cease. In

Cathedral Chapters, if at that date they had been composed partly of Catholic,

partly of Protestant members, the same proportion was to be permanently

maintained. Thus the knot of the old problem—the question of the validity of

the reservation ecclesiasticum—had

been suddenly cut; but practically, so far as the great debatable land of the

west and south-west was concerned, the decision was wholly in favor of the

Catholics. A final stop was put upon the spread of Protestantism in the Empire

by means of conversions in high places. The same rule of date applied to

mediate spiritual foundations—mainly convents; no religious Order was to be

admitted into a convent hitherto held by another, except in the case of its

having become extinct in loco; and

even then no Order founded since the Reformation was to be introduced—a

stipulation palpably directed against the Jesuits.

Of deeper interest to us, because of its connection

with the principle of tolerance which in this generation was only beginning to

dawn upon a few minds, was the problem of the public and private exercise of

their religion by subjects who professed a form of faith different from that of

their territorial sovereign. The declaration in the Peace of equality between

Catholics and Protestants was restricted by the addition in so far as is in

accordance with the constitution and laws of the Empire, and with the Peace

itself; and it had to be reconciled with the right of determining the religion

of his territory (the jus reformamdi) granted by the Religious Peace of Augsburg

to every territorial lord or immediate estate, while to subjects who dissented

there remained the alternative of emigration.

The Lutherans and the Reformed, whom the Catholics

left to settle their own practice on this head, agreed that, without prejudice

to liberty of conscience, existing compacts should continue in force where

Lutherans were actually under a Reformed territorial ruler, and vice versa; and

that in future cases the ruler, while appointing Court-preachers of his own

religion, should not interfere with his subjects’ exercise of their religion,

or with the religious condition which had obtained in churches, schools,

universities, etc., in his dominions at the time of the Peace. The Lutheran

lands about to come under the rule of the Elector of Brandenburg were no doubt

kept especially in view.

For Catholics and Protestants living under rulers of

the opposite faith, the conditions of public and private religious worship, of

the constitution of consistories, and of the patronage and tenure of churches,

convents, hospitals, etc., which had obtained at the most favorable date in the

year 1624, were to be accepted as decisive, and to be maintained semper et ubique (till the day of religious reunion). A single exception was made, in the case

of the see of Hildesheim, where a settlement less

advantageous to the Protestants than the state of things in 1624 was adopted.

In places in this diocese possessed of only a single church, “simultaneous”

Catholic and Protestant worship (i.e. worship at different hours of the same

day) was allowed—an odd compromise largely resorted to elsewhere, though with

very doubtful legal warrant.

Subjects who in 1627 had been debarred from the free

exercise of a religion other than that of their ruler were by the Peace granted

the right of conducting private worship, and of educating their children at

home or abroad, in conformity with their own faith; they were not to suffer in

any civil capacity nor to be denied religious burial, but were to be at liberty

to emigrate, selling their estates or leaving them to be managed by others.

Some ambiguity, however, attaches to the stipulations of the Peace on this

head. One passage provides for the patient toleration of subjects not of the

ruler's religion; but another seems to imply that, exceptions apart, the ruler may

oblige such subjects to emigrate, though without forcibly abducting them or

fixing their destination.

An important and perfectly distinct exception to these

last provisions was however made in the case of the subjects of the House of

Austria. The Emperor Ferdinand II had steadily refused to yield to the demand

pressed upon him in the negotiations for the Peace of Prague that the adherents

of the Confession of Augsburg in his dominions should be allowed the free

exercise of their religion wherever they had enjoyed it in 1612; and a similar non possumus was opposed by Ferdinand III to the proposals made at Osnabruck, where the years

1618 and 1624 were successively named. (The earlier of these was to have

included the Bohemian troubles.) He insisted on his jus reformandi; and Trautmansdorff

repeatedly declared that his master would sooner lose throne and life than

assent to such a demand. Certain concessions were granted in the cases of

the three Silesian duchies of Brieg, Liegnitz, and Münsterberg-Oels, and of the city of Breslau, as well as in

that of the nobility of Lower Austria; but nowhere else in the Austrian

dominions was any exercise of their religion allowed to the Protestants of any

class or condition.

Territorial

rights.

In accordance with the principle of the general

amnesty announced in the Peace, persons who had emigrated from the Austrian

dominions during the course of the War, and who in many instances had taken

service under hostile Princes, were now allowed to return home, but without

recovering either the free exercise of the Protestant religion or the

possession of their lands.

Much trouble between the Confessions had always

existed in the free towns of the Empire. It was now settled that where only a

single religion had been exercised in 1624 the town should be treated as

Catholic or Protestant accordingly; but in certain towns, of which Augsburg was

the most prominent instance, where the adherents of the two religions were

mixed, they were to be equally free to exercise that which they professed. At

Augsburg, however, a complicated arrangement, quite unfair to the large

Protestant majority among the citizens, was adopted as to municipal offices.

From religious grievances we finally pass to

political—though, as in the interesting provisions as to ecclesiastical

jurisdiction, the two fields of discussion lay very close to each other. At the

root of the conflict which had at last become war had lain the opposition

between territorial and Imperial claims. Ferdinand III and his advisers

expressed much surprise on finding that both the Swedish and the French peace

propositions referred so largely to the rights and liberties of the German

Estates; but it was in vain that they sought to postpone to the next Diet.

considerations which possessed so great an interest for the two foreign Crowns.

What was at issue was nothing short of the restoration

of the old territorial sovereignty (Landeshoheit) of the Estates of the realm (a few Imperial

rights’ being reserved), and a fresh statement of certain rights supposed to be

inherent in that sovereignty.

Among these rights, Sweden, France, and the Princes of

the Empire, were above all anxious to place beyond all reach of dispute the

right of concluding alliances, whether with Estates of the Empire or with

foreign Powers. This was effected by the provision, common to both the Treaty

of Minister and to that of Osnabruck, which secured to every Estate the right

of concluding any such alliance with a view to his own security, provided that

it was neither directed against the Emperor, the Empire, or its Landfrieden, nor

against the conditions of the Peace of Westphalia itself. Notwithstanding these

safeguards, a virtually complete independence was thus assured—so far as any of

them could assert it—to each of the 800 or more political bodies which made up

the Holy Roman Empire; and this independence extended to the right of carrying

on war in fulfillment of the obligations of an alliance which any one of these

bodies might have concluded by its own choice.

Conversely, the Estates of the Empire and the two

foreign Crowns were alike interested in seeking to prevent any resort by the

successors of Ferdinand II to arbitrary measures such as those which from

religious or dynastic motives he had adopted in the course of the War—the

pronouncement of the Ban of the Empire against the Elector Palatine, the Edict

of Restitution, the conclusion of the Peace of Prague In spite of the

resistance of the Imperial Government, a clause was inserted in both the Münster

and the Osnabruck Treaty assigning to the Estates of the Empire at large (not

the Electors only) the right of voting in all Imperial business, whether it

concerned legislation or taxation, or the declaration of war or peace. The free

towns, whose position had hitherto been in some measure undefined but on whom

the Empire might at all times reckon as its sincerest upholders, were now placed

on a footing of absolute constitutional equality with the other Estates. In the

treaty between Spain and the States General at Münster the Hanse Towns had been allowed the same commercial privileges towards Spain as the

United Provinces; in the Treaty of Osnabruck Sweden undertook that their

navigation and trade should be maintained in the same condition as before the

War—a strange falling-off from the dominium maris Baltici which

these towns were to have helped to secure to the House of Habsburg.

But of more direct importance for the political future

of the Empire, which must continue to be largely dependent on the relations

between its religious parties, was an innovation logically deduced from the

principle of jura singolorum (Estate rights), upheld by the Protestants in both theory and practice. It was

now provided that in matters of religion (or, as came to be the case, in

matters regarded or treated as such) a majority of votes should no longer be

held decisive at the Diet; but that such questions should be settled by an

amicable “composition” between its two parts or corpora. In other words, by

taking advantage of the jus eundi in partes, the

Protestants might as a body resist any proposal supported, or likely to be supported,

by a numerical majority of Catholic votes. In the same spirit of parity it was

agreed that when possible there should be equality of consulting and voting

power between the “two religions” on all commissions of the Diet, including

those Deputationstage which had come to exercise an authority nearly equaling that of the Diets

themselves. The Reichskammergericht was reformed on a footing of religious equality; the preponderance still

remaining to the Emperor, by virtue of his nomination of two surplus assessors

and of the Kammerrichter or chief justice, being in some measure neutralized by the fact that the

tribunal chiefly acted through its committees (Senates). No attempt was made to

establish religious parity in the Reichshofrath,

whose character as an Imperial council, not subject to a revision of its

decrees, prevented any real assimilation of its procedure to that of the Kammergericht. The Ratisbon Diet of

1653-4 was largely busied with these matters; but they were not brought to a

conclusion by it.

1648-50] Conclusion

of the Peace.—Papal protest.

France and Sweden would gladly have lessened the

prestige of the House of Austria by introducing into the constitution of the

Empire a provision that henceforth no election of a Roman King should be held

during the lifetime of an Emperor. They were also desirous of augmenting the

power of the Estates at large, among whom Sweden was now herself to be numbered;

and France hoped to exercise an enduring influence, by making their assent

requisite for the holding of any such election, and for the settlement of a

permanent Wahlcapitulation limiting the Imperial authority. But the Austrian diplomacy succeeded in

holding over the consideration of these matters for the next Diet. On the other

hand the two Powers were able to delay the actual conclusion of the Peace for

some time after its articles were complete by long discussions as to the proper

ways of executing and of securing it. The Peace was actually signed at both Münster

and Osnabruck on October 27, 1648; but, though the Emperor’s edicts for its

execution were issued a fortnight afterwards, the ratifications were not

exchanged till February 8, 1649. Meanwhile the exchange of prisoners and other

matters appertaining to the execution of the Treaties had been taken in hand by

the military commanders, and were not wound up till June, 1650, at Nürnberg. The protest which the Papal Nuncio had offered

against the Peace immediately after its conclusion, was reiterated a month

later by Pope Innocent X in the Bull Zelo domus Dei (November 26, 1648); but its validity had

been denied beforehand in the Peace itself, and no proceeding could have

demonstrated more palpably the complete estrangement which now prevailed

between the Imperial and the Papal authority. As a matter of fact, the Papal

protest is not known to have been ever invoked by any Power against any

stipulation of the Peace of Westphalia.

| Pope Innocent X (6 May 1574 – 7 January 1655), |

|

Each of the two Powers, whose alliance had prolonged

the War, might now seem to have achieved its ends. The statesmanship of Sweden,

hardly less than the heroic deeds of her great King and a succession of eminent

commanders, had obtained for her the position of a great European Power. But her

losses in men were so serious that a war on a similar scale could hardly be

contemplated by the living or the next generation; while the monarchy could

only defray the financial cost of the effort by processes which ended in

changing the bases of Swedish constitutional life. The Swedish Crown had

acquired a fair German province which provided the security desired by both

Gustavus Adolphus and Oxenstierna for the kingdom itself and for the

sufficiency of its share in the control of the Baltic. Sweden hereby also

secured a permanent right to a participation in the affairs of the Empire, which

might at any time be used for the purpose of once more gaining the control of

them. But she had to reckon with the jealousy of her new neighbor

Brandenburg as well as with old Scandinavian enmities; and the maintenance of

the position which she at present held among the States of Europe could not be

regarded as definitely assured.

Far different was the case with France, who, though

her sacrifices had relatively been far less than those of Sweden, had reaped a

far ampler reward. Besides the recognition of the three sees, she had, by

acquiring Breisach and the right of garrisoning Philippsburg, secured direct access to the German

south-west; and she had taken Austria’s place as the chief Power in Alsace.

Though she had not herself acquired a place in the system of the Empire, the

relations into which she had entered with certain of its Estates furnished

arguments for the support of future claims to an extended sovereignty. And—most

important of all—besides opening future opportunities of intervention in the

affairs of the Empire, the War and the settlement which ended it enormously

increased her moral ascendancy in western Germany and in the Empire at large.

By consenting to these losses the House of Austria and

the Empire which had so long accepted its headship had purchased a necessary

peace. To the House of Austria this meant the preservation to it of the great

mass of its dominions, and of so much authority as in the eyes of Europe and of

the Empire still remained inseparable from the tenure of the Imperial Crown.

But to the Empire at large it meant the settlement of the grievances for the

redress of which Catholics and Protestants alike had, sooner or later, appealed

to the decision of war, or responded to that appeal when it presented itself

before them. The religious settlement, however imperfect from the point of view

of later times, secured to the Protestants—and to the Calvinists as well as to

the Lutherans—the “equality” for which they had been so long contending, though

the point of time which determined the partition of rights and possessions

between them and the Catholics had to be more or less arbitrarily fixed. The

maintenance of this “equality” within the Empire was guaranteed by a

constitutional change of the highest importance introduced into the procedure

of the Diet; and the opportunities of the Counter-reformation had passed away

forever. On the other hand, the provision made for individual freedom in the

exercise of any one of the recognized religions was insufficient; and from the

dominions of the House of Austria as a whole Protestant worship was

deliberately excluded.

Among the changes introduced by the Peace of

Westphalia into the political life of the Empire, and contributory to that

complete establishment of their “liberties” which its Estates had consistently

striven to secure, the most important was the full recognition of their right

to conclude alliances with foreign Powers. The Empire thus in point of fact

came to be except in name little more than a confederation; but inasmuch as its

Estates were numerous and a large proportion of them petty and powerless, with few securities for

their rights and an endless divergence of interests, the dissolution of the

bond that held them together must sooner or later follow; more especially if

the historic ascendancy of the House of Austria and its traditional tenure and

transmission of the Imperial dignity should cease to endure.

But the political losses and gains which the Peace of

Westphalia entailed upon the Empire and its Princes sink alike into

insignificance, and even the undeniable advance towards religious freedom

marked by the adoption in that Peace of the principle of equality between the recognized

religious confessions is obscured, when we turn to consider the general effects

of the War now ended upon Germany and the German nation. These effects, either

material or moral, cannot be more than faintly indicated here; but together

they furnish perhaps the most appalling demonstrations of the consequences of

war to be found in history. The mighty impulses which the great movements of

the Renaissance and the Reformation had imparted to the aspirations and efforts

of contemporary German life, were quenched in the century of religious conflict

which ended with the exhausting struggle of the Thirty Years’ War; the

mainspring of the national life was broken, and, to all seeming, broken forever.

Economic and

social effects of the Peace. Agriculture.

The ruin of agriculture was inevitably the most

striking, as it was the most far-reaching, result of this all-destructive war.

Each one of those marches, counter-marches, sieges, reliefs, invasions,

occupations, evacuations, and reoccupations, which we have noted, and a far

larger number of military movements that we have passed by, were accompanied by

devastations carried out impartially by “friend” or foe. For the peasants who

dwelt upon the land there was no personal safety except in flight; their

harvests, their cattle, the roof over their heads, were at the mercy of the

soldiery; and, as the War went on, whole districts were converted into deserts.

Bohemia, where the War broke out, had the earliest

experience of its desolating effects, above all in the sorely tried north-west

of the kingdom; but its sufferings reached their height—long after the Bohemian

rising had been crushed, as it seemed, for ever—early in the last decade of the

War. The destruction of villages, from which most parts of the Empire suffered,

was probably here carried to the most awful length; of a total of 35,000 Bohemian

villages, it is stated that hardly more than 6000 were left standing. The

sufferings of Moravia were in much the same proportion, and even more

protracted; those of Silesia only ended when it was made over by Saxony into

the Emperor's care at the Peace of Prague. Upper and Lower Austria also enjoyed

some relief during the last part of the War, when the main anxiety of the

Emperor was to keep it out of his hereditary dominions. The inflictions to which

Maximilian’s electorate was subjected during the victorious campaigns

of Gustavus Adolphus and the subsequent invasion of Bernard of Weimar were

followed by far more grievous treatment by the troops of Banér and Königsmarck.

During the concluding years of the War no other German land underwent more

terrible sufferings than Bavaria, where—especially in its eastern part—famine

and desolation stalked unchecked. Franconia and Swabia, too, were made desolate

by the ravages of war, famine and disease, especially after the catastrophe of Nordlingen; the pasture-lands of the Schwarzwald and the vineyards of the Upper Rhine and Neckar country were alike desolated.

The Lower Palatinate, when this portion of his patrimony was at last recovered

by the Elector Charles Lewis, was little better than a desert; so utterly had war,

anarchy, and emigration changed the face of the garden of Germany. The regions

of the Middle Rhine were in little better plight than those of the Upper;

Nassau and the Wetterau had suffered unspeakably,

especially during the latter part of the War, and the Hessian lands but

slightly more intermittently. In the north-west neither the Brunswick-Lüneburg

lands nor even remote East Frisia had escaped the

scourge of military occupation; in Calenburg (Hanover) whole forests had been cut down by the Swedes. In central and

north-eastern Germany, Brandenburg and Saxony had during nearly two-thirds of

the War been at no time free from occupation or raids, especially on the part

of the Swedes; the Anhalt principalities had suffered as if to atone for

Christian’s share in lighting the flames of war; and the Mecklenburg Dukes on

their return home found the land desolate and depopulated.

The depopulation of Germany was an even more ominous

feature in the aspect of the Empire after the War than the devastation of its soil.

The statistical data at our command rest on no very satisfactory bases; but a

comparison of statements as to particular territories seems to show that the

population of the Empire had been diminished by at least two-thirds—from over

sixteen to under six millions. In accounting for the loss it was reckoned (but

how could this reckoning be verified?) that not far short of 350,000 persons

had perished by the sword; famine, disease, and emigration had done the rest.

In particular territories the loss of population had been enormous. In the

Lower Palatinate only one-tenth (for the much-quoted figure of one-fiftieth

must be dismissed as fictitious), in Wurttemberg one-sixth survived; in

Bohemia, where, as in the Austrian duchies, emigration had largely helped to

depopulate the country, it was reckoned that already before the last invasions

of Banér and Torstensson the total of inhabitants had

since the opening of the War diminished by more than three-fourths.

The peasantry

and the towns.

Notwithstanding the terrible sufferings which the War

had inflicted upon the unprotected peasantry in by far the greater part of the

Empire, this unfortunate class were by no means relieved from the burdens

ordinarily imposed upon them. The poll-tax and the taxes on articles of

consumption were exacted where it was possible to levy them; the services

(Frohnen)

were raised to so enormous a height during the War as to convert the position

of a large proportion of the peasantry into one of serfdom, without the

advantages of a fixed tenure which there was no legal means of ensuring. An

inevitable result of the devastations due to the War was the practical afforestation of large tracts of arable land, and the

imposition on the peasantry of a fresh burden of services, besides the infliction

of endless damage, arising out of the chase. To these evils was added the

insecurity of life and property due to vagabondage—the inevitable accompaniment

and the long-enduring consequence of wars carried on by mercenaries, and more

especially of one conducted on an unprecedented scale and extending over so

large a part of Europe.

The economic effects of such a condition of things

upon the soil and its cultivators need not be discussed at length. During more

than a generation after the conclusion of the War a full third of the land in

northern Germany was left uncultivated. Cattle and sheep diminished to an

extraordinary extent, and many once fertile districts became forests inhabited

by wolves and other savage beasts. The cultivation bf many products of the land

passed out of use in particular districts or altogether. Prices fell so low