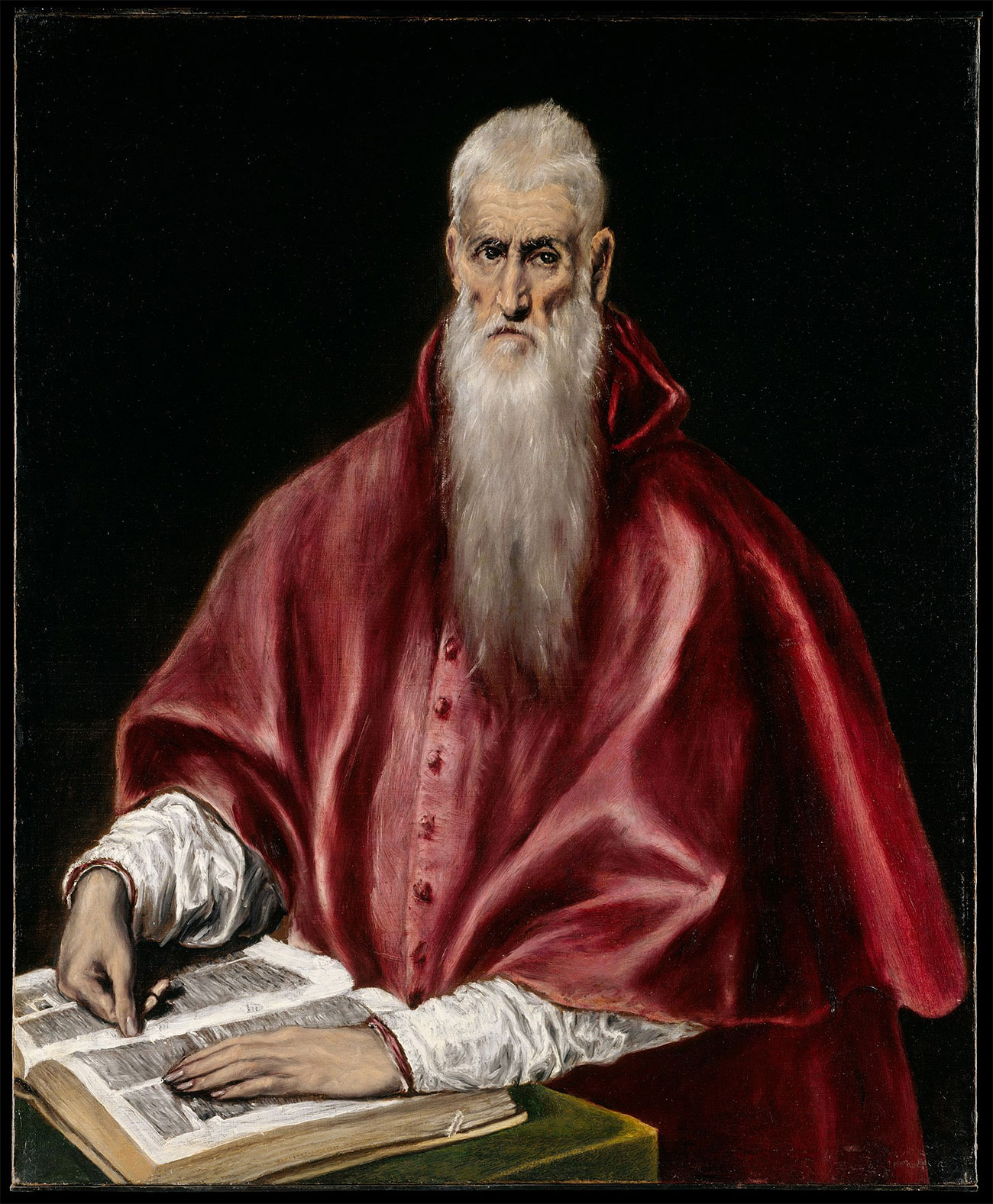

Rev. EDWARD L. BUTTS

CHAPTER I. a.d. 346-363. Birth and Education of Jerome

The city of Aquileia— The village of Strido—

Jerome born there, A.D. 346— Of Dalmatian race, of

Christian family— Sketch of political and ecclesiastical history during the

period of his boyhood.

CHAPTER II. A.D. 363. Rome in the

Fourth Century

Its architectural splendour— Its political decadence— no longer the seat

of empire, but still inhabited by the great ancient families— Its wealth and

luxury— The worship of the Gods of ancient Rome still maintained in splendour,

but the Church numerous and powerful— Description of the city: the Campagna, the

tombs, the suburbs, the streets, the Forum, the population.

CHAPTER III. A.D. 363-367. Student

Life in Rome

The organization of the Roman schools— The course of study— Student

life— Holiday visits to the tombs of the martyrs— Contest between Damasus and

Ursicinus for the See of Rome— Storming of the Basilica of Sicinius— Riots— Punishments— Election

of Damasus confirmed— Jerome goes to Traves— His “conversion”— Returns to Rome.

CHAPTER IV.The Patrician Devotees of Rome

Development of Asceticism in the Church— Antony, Pachomius, Macarius,

Ammon, Hilarion —Athanasius visits Rome, with Ammon and Isidore — Their ascetic

teaching— Its acceptance among the noble ladies of Rome— Opposition of the Pagan

nobles, of the clergy, of the people— Parallel with our own time— Apology of

asceticism— The ladies of the school of the Aventine Mount: Eutropia, Abutera, Sperantia,Marcella, Sophronia, Asella, Furia, Fabiola, Marcellina,

Felicitas, Melania— Jerome’s name connected with that of Melania— Melania leaves

Rome for the East.

CHAPTER V. a.d. 367-373. Jerome embraces the Ascetic Life

Jerome returns from Rome to Aquileia— Embraces the ascetic life with

Paulinian, Bonosus, Rufinus, Heliodorus, Chromatius, Eusebius, Jovinus, Inno- centius, Nicias, Hylas.

Jerome and Paulinian retire to Strido—Dispute with

the bishop— Seek solitude in the country— Return to

Aquileia— Jerome and his friends set out with Evagrius for the East.

CHAPTER VI. A.D. 373-378. Antioch

and the Desert of Chalcis

Site of Antioch— Description of the city— Historical interest of its

church— Divisions in the Church of Antioch between the parties of Meletius,

Paulinus, Euzoius— Story of Malchus the hermit— Jerome retires to the desert of Chalcis— Description of the

desert— Letter to Heliodorus— The bright side of the ascetic life— Its dark

side— His studies in the desert— His vision of Judgment— Affairs of the Church of

Antioch— Doctrinal dispute on the use of ousia and

hypostasis— Apollinarian heresy— Further schisms. The controversies taken up by

the hermits of the desert— Jerome disturbed by them— Quits the desert, and

returns to Antioch—Ordained priest under protest— Probable visit to

Palestine— Goes to Constantinople. .

CHAPTER VII. A.D. 379-382. New

Rome

Site of Constantinople— Description of the city— The growth of its

Church— The East distracted by the Arian heresy, while the West had peace— Accession

of Theodosius— Mission of Gregory of Nazianzum to

Constantinople— Elected to the See— Maximus intruded into the See by the

Alexandrians— Council of Constantinople, April, 381 A.D.— Its proceedings— Council

summoned at Rome— Eastern bishops decline to attend— Jerome appointed secretary

of the Council— Its proceedings.

CHAPTER VIII. A.D. 382-385. The

Secretary of the Roman See

Damasus appoints Jerome secretary of the See— His confidence in

him— Invites him to revise the Latin version of the Gospels— History of the

Latin Bible— First translated in Africa— The old Latin version revised in North

Italy— The Italic version— Texts had become corrupt— Jerome’s revision.

CHAPTER IX. A.D. 382-385. The

Spiritual Director

Jerome’s ascetic teaching— Present state of the Ascetic school in

Rome— Marcella and Albina— Pammachius, Oceanus,

Marcellinus, Domnion, Paula and her daughters— Blesilla’s conversion ; becomes a Church-widow— Jerome’s

defence of her— Satirizes the Pagan society of Rome.

CHAPTER X. A.D. 382-385. The

Controversy with Helvidius and Jovinian

Helvidius writes a book against Jerome— Jerome replies— His defence of virginity— Sketch of

domestic manners— Jovinian writes a book against

Jerome— Jerome’s reply.

CHAPTER XI. A.D. 382-385. The

Mirror of the Clergy

Character of the Roman clergy: greed, wealth, and luxury— Eustochium

becomes a Church-virgin— Jerome’s letter to her— A treatise on Church-virginhood— Satirizes the Christian society of Rome— Replies to Onasus of Segeste.

CHAPTER XII. a.d. 384. The Death of Blesilla

Death of Blesilla— Her funeral—nThe popular demonstration against

asceticism—nJerome’s letter to Paula on the death of Blesilla.

CHAPTER XIII. a.d. 385. Jerome’s Defence

Death of Damasus—nSiricius elected to the See—

Jerome’s disappointment on not being elected—nHis friendship with Paula— Public

scandal— They resolve to quit Rome and go to the East— Jerome’s defence— He sails

for Antioch.

CHAPTER XIV. a.d. 385. The Pilgrimage to the Holy Land . Page

Paula and Eustochium quit Rome— Visit Cyprus— Are entertained by

Epiphanius— Arrive at Antioch— Jerome’s party and Paula’s party join company,

and proceed to the Holy Land— Description of the country, of Jerusalem— Visits to

the holy places, to Bethlehem, to Egypt

CHAPTER XV. A.D. 385. Egypt

Site of Alexandria— Description of the city— Its church— Theophilus the

bishop— Didymus the master of the schools.

CHAPTER XVL The Fathers OF the Desert

Description of the desert— The Nitrian Mountain, its monastery, its cells— Of the valley of Scete, its monastery— The

monastic life— Visits to the hermits — The eremitical life— Serapion— Pambon— Return to Bethlehem.

CHAPTER XVII. a.d. 386-389. Bethlehem

Site and description of the city— The Khan of Chimham— The

cave of the Nativity— The Basilica of Constantine— Jerome and Paula settle at

Bethlehem, purchase land and build monasteries— Jerome’s plan of life—Opens a

school— His Hebrew studies— Share of Paula and Eustochium in his studies and

works— His replies to his detractors.

CHAPTER XVIII. A.D. 389. Life in

the Convents of Bethlehem

Description of the monasteries— The mode of life of the nuns— Of the

monks— Paula and Eustochium’s letter to Marcella,

describing Bethlehem and their life— Jerome’s postscript.

CHAPTER XIX. HIS Literary Works

Commentaries on the Old and New Testaments— Controversial

works— Treatises on the ascetic life— Letters— Funeral Orations— Translations of

the Old and New Testaments— Value of the Vulgate Bible— Its gradual acceptance

in the Church.

CHAPTER XX. A.D. 395. The Origenistic Controversy

Ecclesiastical rank of the Church of Jerusalem— Intercourse between

Jerusalem and Bethlehem— Writings and character of Origen— Revived controversy

about his orthodoxy; begun in Egypt, spreads to Palestine— Epiphanius preaches

in Jerusalem against Origenism— John the bishop replies— A schism arises— Jerome

and his communities take the side of Epiphanius— John

lays the communities of Bethlehem under interdict— Interposition of Theophilus

of Alexandria— Theophilus’s change of policy— Reconciliation of communities of

Jerusalem and Bethlehem — Quarrel of Theophilus and Epiphanius with Chrysostom— Jerome

on the side of Theophilus.

CHAPTER XXI. A.D. 395. The Visit

of Fabiola

Cosmopolitanism of this period— Multitude of pigrims

to the Holy Land— Visit of Fabiola— Alarm of the invasion of the Huns— Fabiola’s

case considered— Jerome’s reply— Her penance. .

CHAPTER XXII. a.d. 395-404. The Apologia in Rufinum

Rufinus in Rome, teaches Origenism— Rufinus attacks Jerome— Jerome

replies— Vigilantius frites against Jerome— His

reply— Death of Nepotian.

CHAPTER XXIII. A.D. 397-403. The

Death of Paula

The death of Paulina— Her funeral—Conversion of Toxotius— Birth

of Paula junior— Jerome’s letter on her education— Sickness of Paula— Her death

and funeral— Her epitaph.

CHAPTER XXIV. a.d. 395-407. The Controversy with Augustine

Jerome’s relations with great Churchmen— Augustine writes two letters

against Jerome— Jerome’s replies— The controversy on Paul’s rebuke of Peter.

CHAPTER XXV. A.D. 406-418. The

Fall of Rome.—Fugitives at Bethlehem

The invasion of the barbarians— The sack of Rome by Alaric— Fate of the

fugitives— The scandal of Deacon Sabinianus— Pelagius, his heresy— Acquitted at

Jerusalem and Caesarea— Attack on the Bethlehem monasteries— Death of Eustochium.

CHAPTER XXVI. a.d. 418-420. The Death of Jerome

He had survived his friends— His sickness— His death— His tomb.

CHAPTER I

BIRTH AND EDUCATION OF JEROME,

A.D. 346-363.

In the middle of the

fourth century the city of Aquileia was the capital of the province of Venetia,

and one of the grandest cities of Italy. It was situated at the northern bend

of the Adriatic Sea, a little eastward of the cluster of low islands upon which,

a century afterwards, its inhabitants, fleeing from the invading Huns, founded

modern Venice.

Lying on the one great highroad into Italy from the side of Illyria and

Pannonia, the city was a great commercial emporium; while its situation, commanding

the whole country between the mountains and the sea, made it of great military

importance in the defence of the peninsula; it was therefore strongly

fortified, and was the chief military station of the north-east frontier of

Italy.

Here, in the year 340 a.d., the younger Constantine was defeated

and slain, almost beneath the city walls, and his brother Constans became

emperor of the undivided West. The place and the event serve to mark the birth

of the subject of this essay. The exact situation of the village of Strido, the birthplace of Jerome, is lost, but it is known

that it was near Aquileia, on the road which ran from that city northward to

Emona, and probably just at the point where the road crosses over Mount Ocra, part of the chain of the Julian Alps. The exact date

of his birth is uncertain, but it was most probably about six years after the

death of Constantine II in the battle outside Aquileia.

In Strido, then, a suburban village of

Aquileia, about the year 346 a.d., Constans ruling the Empire of the West

from Milan, and Constantius, in Constantinople, ruling the Empire of the East,

was born Eusebius Hieronimus Sophronius, commonly

known to us by the modern form of his second name, Jerome, the first, and the

most learned and eloquent, of the Fathers of the Latin Church.

He was probably of Dalmatian race. His father possessed a small landed

estate, and seems to have been a person of respectable social position. He had

a brother, Paulinian, and a sister. Since, in the biographical allusions which

abound in his writings, he nowhere mentions his mother, it is probable that she

died before he was old enough to remember her. His family was Christian, and he

was brought up in the Christian faith; but he was not baptized in infancy. It

was, at that period, a common practice, though reprobated by the Church, to

delay Baptism till some spiritual crisis, or the approach of death, under the

idea that sin in the unbaptized was less heinous, and that baptism would at

length wash away all the sins of the previous life. He was carefully educated

at home by a tutor; and Bonosus, the son of a rich

neighbour, who seems to have been his foster-brother, and was the inseparable

companion of his early years, was educated with him.

Thus he grew up into manhood amidst the local influences of a residence

between the mountains and the sea—the Alps and the Adriatic; and under the

social influences of the rude, energetic Dalmatian and Pannonian peasantry and

farmers on one side, and on the other of the civilization of the neighbouring

metropolis of the province.

The political and religious history of the period during which the boy

was growing up into manhood was too remarkable not to have had an influence

upon an ardent and talented youth. His boyhood from seven to fifteen was passed

in the period in which Constantius, now by the death of his brother sole

emperor, was endeavouring to coerce the Western Church into the acceptance of

the Arianism long predominant in the East. The general persecution, the conduct

of Liberius, Bishop of Rome, his brave resistance,

his exile, the intrusion of Felix into the see, Liberius’s acceptance of an ambiguous creed, his return, the schism between his party and

that of Felix—these were questions which agitated Italian society, and were

discussed in every Christian home. The Council of Rimini, “when the whole world

groaned, and was astonished to find itself Arian,” took place when Jerome was

fourteen, and the words we have quoted are the record in after years of his own

recollection of the event Then came the death of Constantius, the accession of

Julian, his apostasy, his endeavour to revive the belief in and the worship of

the ancient gods of Rome, his tragical death in the Persian campaign, the

succession of Jovian, and the final triumph of Christianity—these were the

public events in the midst of which the youth passed his fifteenth, sixteenth,

and seventeenth years. Jovian’s short reign passed, and Valentinian sat on the

throne of the West, making Treves the Imperial residence, when, at the age of

seventeen, Jerome was sent, together with Bonosus, to

complete his education at Rome.

CHAPTER II

ROME IN THE FOURTH CENTURY.

A.D. 363

Rome in the fourth century was in the period of its very greatest extent and

architectural magnificence. The series of public buildings and monuments with

which a succession of emperors and great nobles had adorned the Mistress of the

World—the temples, basilicas, palaces, forums, colonnades, triumphal arches,

statues, theatres, baths, and gardens—had been completed by the triumphal arch

with which Constantine commemorated his victory over Maxentius; and the whole

series was still uninjured by time or violence.

And the city had lost, as yet, little of its ancient population and

wealth and splendour. It is true it had ceased to be the seat of the world’s

government and the centre of the world’s affairs. From the beginning of the

reign of Diocletian (a.d. 277), that is, for a space of nearly a hundred years, the Emperors had ceased

to reside in Rome. Under the new organization which that able statesman had

given to the empire, the sovereigns no longer kept up the ancient forms of the

Republic, under which the earlier Caesars had decently veiled their power. They

had found it desirable, for military reasons, to place the seats of Government

at more convenient centres, and politic to remove their courts from the

influence of the antique Republican spirit which still survived in Rome, and

from the rivalry of the great patrician houses. Constantine had built and

adorned Constantinople as the capital of the new empire; and when the Imperial

authority was divided, the emperors of the West had chosen Milan for their

residence, and had enlarged and adorned and fortified the city till, in the

words of a contemporary poet, “it did not feel oppressed by the neighbouring

greatness of Rome.” In these new capitals of the East and West the joint

emperors exercised their absolute rule; took counsel only with advisers of

their own choice, made and unmade at pleasure the great ministers of State, the

governors of the provinces, the generals of the armies; surrounded themselves

with eunuchs and guards, and with the etiquette of Eastern royalty, and the

splendours of a parvenu Court. At Rome, meantime, the great patricians still

resided. Left outside the new Imperial constitution, they on their part had

held themselves aloof from the new order of things. They had not deserted the

city to swell the splendour of the new Courts, but still occupied their vast

palaces on the hills of Rome, dignified with the busts of great ancestors, and

adorned with the spoils of provinces; they still drew immense revenues from the

produce of estates and the tribute of cities scattered over the Roman world. If

some of the great ancient families had been destroyed or impoverished by the

jealousy or cupidity of the Caesars, new families had risen in their place,

who, if they had a less noble ancestry, had wealth which enabled them to vie

with the ancient families in ostentation, and who often supplied the lack of

pedigree by imaginary claims of descent from the heroes of ancient story.

These great houses still retained their numerous households of slaves, and

still found employment for the traders and craftsmen of the city. The Senate,

though deprived of all share in Imperial affairs, and reduced to the functions

of the municipal government of Rome, still, from the rank of those who composed

it and the great traditions which it inherited, retained something of its

ancient prestige.

The poorer citizens had long ceased to enrol themselves in the legions;

they disdained to exercise trade or handicraft; they clung to their faded

dignity as Roman citizens; maintained existence by help of public doles, and

spent their days in the taverns, the amphitheatres, the baths, and the public

places.

It was but tod natural that such a population, excluded from the

ennobling occupations of the State, should fall into a life of luxury and

dissipation. The contemporary historians give vivid pictures of the boundless

prodigality and luxury of the nobles, their effeminacy, frivolity, and

dissoluteness; and of the greed, corruption and turbulence of the mob.

The religious condition of this population was remarkable. The nobles

had clung to the ancient gods of Rome as part of the old order of things, which

had bequeathed to them their greatness, in opposition to Christianity, which,

since Constantine, was an essential feature of the new order. The offices of

Pontiff and Augur were still sought by the most illustrious members of the

Senate, and “the dignity of their birth reflected additional splendour on

their sacerdotal character. Their robes of purple, chariots of state, and

sumptuous entertainments, attracted the attention of the people; and they

received from the public revenue an ample stipend which liberally supported

the splendour of the priesthood, and all the expenses of the worship of the

State.” Many of the noble houses had hereditary cults, much as in

later times the great mediaeval families had their patron saints. The temples

and shrines were still maintained, and the sacrifices and solemnities

celebrated with all their accustomed pomp in Rome, while the provincial temples

were mostly destitute of priest or sacrifice, and were falling into decay.

At the same time the Christians were numerous in the city, and the

Church was well organized, wealthy, and influential. So long ago as the time of

Diocletian, there were in Rome and its environs, twenty-five public churches

and fifteen suburban basilicas connected with the catacombs. Constantine had

given several new basilicas to the Church. And the number of the churches, and

still more, the number of the priests, deacons, and minor officials of the

Church, during nearly a century of freedom from persecution had, doubtless,

greatly increased. What is specially notable is, that

the female members of the noble families were generally Christian, even while

their fathers and brothers, husbands and sons, still refused the new faith. The

voluntary donations of the wealthy members of the Christian body furnished the

Church with ample revenues. The Bishop maintained a sumptuous establishment, and

kept a table and an equipage, which rivalled those of the wealthy nobles. The

clergy were received in the palaces of the Patriciate, and were enriched by the

offerings of the wealthy members of their flocks. The influence of the Church

was maintained among the lower class of the people, by a numerous and

well-organized clergy, and fostered by the regular distribution of large

charities.

This was the magnificent and luxurious, half pagan and half Christian,

Rome, to which our young Dalmatian, with his foster-brother, came up as to a

university to complete his education.

Emerging from the defiles of the Sabine hills, upon a wide

plain of coarse, luxuriant pasturage, dotted over

with herds of cattle, they would descry in the centre of the plain an isolated

cluster of low hills, crowned with a vast assemblage of temples and palaces,

surrounded by their groves and gardens, while the interspaces of the hills

were filled with the clustering houses which spread around their feet in all

the vastness of the greatest city of the world.

They would approach it by the Flaminian Way. For miles outside the city

gate the tombs and mausoleums of twenty generations bordered the road,

interspersed with the spreading ilex and funereal cypress. Some of these tombs

were of considerable size and architectural pretensions, palaces of the dead each

containing the ashes of the members of a noble family, with those of their

freedmen and slaves; others were of lesser size and sumptuousness, down to the

simple upright head-stone, with its brief epitaph.

As they reached the city, they saw on their left the Pincian hill, occupied in that day, as in this, by villas and gardens; from its flank

descended the lofty arches of the aqueduct of Agrippa. On their right lay the

Campus of Agrippa, a public park, with gardens and porticos, which Augustus had

adorned with a host of statues, taken chiefly from the overcrowded Capitol.

They would soon find themselves passing, by the Via Lata, through the northern

suburb; the abrupt escarpment of the Capitoline hill rising before them, and

excluding the view of the city. A winding of the street to right and left again

would take them round the base of the Capitoline, and into the Forum, where

they would be in the very heart of Rome.

They would see an oblong marble-paved “Palace,” entered by triumphal

arches, surrounded by colonnades, lined with temples and basilicas, crowded

with statues. The steep height of the Capitol rose on one side, crowned with

the grand group of buildings which composed the temple of Jupiter; on the other

side, the Palatine, crowned with the temple of Julius and the Palace of the

Caesars; all the surrounding heights sustaining clusters of temples and

palaces, surrounded by groves and gardens; and right in front the colossal

Flavian Amphitheatre. The streets through which they would pass, in the valleys

between these eminences, were narrow and winding, with lofty brick houses of

many stories, steep gabled, and with over hanging balconies,

making the streets cool and shady under the Italian sun. Forum and streets, in

the pleasant evening, would be thronged with all ranks and classes of the gay

luxurious city. Gentlemen in embroidered mantles, some strolling under the

colonnades, some lounging in groups in the apothecaries’ shops, which were

then the centres of all the news and all the scandals of the city, as in later

times were the barber’s shops; ladies in litters of ivory and gold, borne by

tall Liburnian slaves trained to walk with regular elastic step, preceded and

followed by eunuchs and slave women; the lady herself in silk robe of the

lightest texture, rather revealing than veiling her charms, covered with

jewels, her hair dyed gold-colour, intermixed with threads of gold and

elaborately dressed, her beauty heightened with powder and rouge and darkened

eye-lids; citizens and their wives; slaves of all nations and conditions, from

the courtly Greek majordomo, or physician, or the staid pedagogue of some

great house, down to the negress drudge of some poor craftsman’s cabin; gentle

and simple, young and old, bond and free, patrician and parasite, gladiator,

priest, student, ballad-singer, water-carrier, and slave—all full of life and

gaiety, then as now, on a voluptuous summer’s evening, in the streets and

public places of Rome. Our provincial youths would, probably, on the first day

of their arrival, wander through all this magnificence and gaiety, and at

length find a lodging high up in one of the tall houses of the Suburra, and settle down for the first evening in their student’s

chamber, wearied and bewildered, and feeling painfully their own insignificance

amidst the crowd and the splendour.

CHAPTER III

STUDENT LIFE IN ROME.

A.D. 364-367.

The Emperor Valentinian seems to have revised the educational institutions of the

Empire. It was his intention that the arts of rhetoric and grammar should be

taught, in the Greek and Latin languages, in the metropolis of every province;

and as the size and dignity of the school were usually proportioned to the

importance of the city, the academies of Rome and Constantinople claimed a just

and singular pre-eminence. Fragments of the edicts of this Emperor for the

organization of the school in Constantinople happen to remain, and, no doubt,

fairly represent what was the organization of the school of Rome also. That

school consisted of thirty-one professors in different branches of learning;

viz., one philosopher, and two lawyers; five sophists, and ten grammarians for

the Greek; and three orators, and ten grammarians for the Latin tongue; besides

seven scribes, or, as they were then styled, antiquarians, whose laborious pens

supplied the public library with fair and correct copies of the classic

writers. The rule of conduct which was prescribed to the students is the more

curious, as it affords the first outlines of the form and discipline of a

modem university. It was required that they should bring proper certificates

from the magistrates of their native province; their names, professions, and

places of abode, were regularly entered in a public register; the studious

youth were severely prohibited from wasting their time in feasts or in the

theatre; and the term of their education was limited to the age of twenty. The

Prefect of the city was empowered to chastise the idle and refractory by

stripes or expulsion; and he was directed to make an annual report to the

Master of the Offices, that the knowledge and ability of the scholars might be

carefully applied to the public service.

The famous Donatus was, at that time, one of the teachers in the schools

of Rome, and Jerome and Bonosus had the advantage of

his instruction. The regular course of instruction consisted of grammar, the

study of the chief Greek and Latin writers; rhetoric, the practice of writing

and declaiming speeches on all kinds of subjects, which was considered to be

the best way to assist the young mind to store up and arrange knowledge, to

exercise thought, and to acquire the art of oratory, then so highly esteemed;

dialectics, or the art of reasoning and disputation, which added acuteness and

readiness to learning and eloquence.

Jerome’s natural talent and his industry enabled him to gain a

distinguished position in the studies of the Schools; and he acquired a

considerable reputation for learning and eloquence. He had, besides, a natural

turn for letters; and he bought books, or made copies of them with his own

hand, and gradually collected a library. The discipline of the schools of that

day, it will be seen, resembled that of the German rather than of the English

universities of the present day; the system was professorial, not tutorial; the

supervision of the Prefect of the city could be little more than nominal; and

the students were practically under no domestic discipline; their own moral

principle and discretion were their only guardians amidst the temptations of

the capital; and Jerome laments in one of the writings of his maturer years, that his youth and inexperience had

succumbed under these temptations.

It is not difficult to picture to ourselves this student life in Rome.

The long hours of hard study in the chamber which the two foster-brothers inhabited,

in the upper story of one of the tall brick houses; the attendance on

professors’ lectures, and the declamations and disputations in the schools; the

pleasant evenings spent in the Forum, amidst all the wealth and fashion of the

capital; the occasional visits to the Flavian Amphitheatre—in spite of the

Imperial prohibition—and to the baths of Caracalla or Diocletian, and the

gardens of Agrippa. One incident, however, of this student life, which would

not, perhaps, have occurred to our imaginations, is suggested by Jerome

himself, where he tells us that he used on Sundays, with his companions, to

visit the catacombs, and to read the inscriptions on the tombs of the bishops

and martyrs. The cessation of the ages of persecution had naturally inclined

the present age to look back upon those heroic times of the Church with a

sentiment of reverent admiration. Damasus, the archdeacon, had written

eulogistic epitaphs on the ancient bishops, and attached them to the loculae, hitherto marked only by a name. The visitation of the tombs of the martyrs

began to be a popular form of piety. This scrap of Jerome’s student life

enables us to realize the crowd of Roman Christians making a holyday visit to

the suburban cemeteries; defiling, with reverent curiosity, through the narrow

subterranean galleries; gazing on the graves which lined their sides, spelling

out the brief inscriptions, and guessing at the meaning of the symbols, rudely

sculptured upon the slabs which closed them.

It was during Jerome’s student life at Rome that Liberius,

its bishop, died, and the famous contested election occurred, which placed

Damasus in the Episcopal chair.

There were two candidates, the representatives of two parties among the

Roman Christians. Damasus represented the party which had rigidly maintained

the orthodox faith during the persecution of the Western Church by Constantius,

and had rallied round Liberius on his return from

exile. Ursicinus was the candidate of the laxer party, the party which had surrounded

the rival bishop Felix, who had been thrust into the See by Constantius during Liberius’s exile. It is said that personal ambition also

had its influence in the contest which ensued for the great position of Bishop

of Rome; for already, as we have said, it had become a position of wealth and

power. The contemporary historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, says: “No wonder that

for so magnificent a prize as the Bishopric of Rome, men should contest with

the utmost eagerness and obstinacy. To be enriched by the lavish donations of

the principal females of the city; to ride, splendidly attired, in a stately

chariot; to sit at a profuse, luxuriant, more than imperial table,—these are

the rewards of successful ambition.”

At the election, which took place in the Church of St. Laurence, the

votes were nearly equally divided; Damasus was declared by the presiding

officer to be elected, but the partisans of Ursicinus disputed the decision.

The two parties came to blows, and the blood of the combatants flowed freely.

The party of Damasus remained masters of the field; and Damasus was

consecrated by the Bishop of Ostia, to whom tradition assigned the privilege of

consecrating the Bishops of Rome.

But the dissension was not thus terminated. Ursicinus denounced the

election of his rival as null and void, and of his own authority convoked the

people for another election in the Basilica of Sicinius on the Esquiline Mount. The partizans of Damasus,

armed with axes swords, and clubs, attempted to force an entrance into the

Basilica, in order to interrupt the proceedings, and disperse the assembly. A

guard of soldiers, sent by the Prefect of the city to disperse the illegal

meeting, marched up in the midst of the tumult. But the Ursicinians barricaded the doors of the Basilica, and refused entrance to both soldiers and

crowd. Then the people climbed to the roof of the building; pulled off the

tiles, and flung them down upon the heads of the assembly within; the soldiers

also assaulted them with arrows and javelins. At last the building was set on

fire. Then the terrified Ursicinians, with the

courage of despair, opened the doors and sallied out; succeeded in forcing a

passage through their besiegers; and dispersed in the neighbouring streets.

When the conquerors entered the Basilica they found the pavement flooded with

gore, and covered with the wounded and dying; they took out—one account says,

137—another says, 160 corpses. Ursicinus, however, had gone through the

ceremony of an irregular consecration, and had made his escape.

The whole city was filled with the rioting of the rival parties. The mob

joined the rioters for the sake of plunder. The military Prefect, Juventius,

withdrew the troops outside the city, whether afraid of their being

overpowered, or to prevent a sanguinary collision, does not appear. Maximinus,

the Civil Prefect, also withdrew from the city. The Ursicinians took possession of most of the churches, and Ursicinus went from one to another,

ordaining a great number of priests and deacons, so as to surround himself with

a clergy; a sufficient indication that the existing body of the clergy

acknowledged Damasus; which, again, is a strong evidence of the legitimacy of

his claim. At last the commotion began to subside; Juventius re-entered the

city, and drove out the Ursicinians, who took refuge

in the suburbs, and occupied the cemeteries and suburban churches, whence they

had again to be driven by force; the Basilica of St. Agnes-without-the-walls

was taken by assault. Meantime, Maximinus made numerous arrests; examined the

accused by torture; inflicted fines, imprisonment and banishment so lavishly

and indiscriminately, as to bring great odium, not only upon himself, but upon

Damasus and his party. All Italy was moved by the contest. Ursicinus went from

diocese to diocese seeking support, and demanding a council to decide between

himself and his rival; and carried his complaints to the Emperor Valentinian.

Damasus similarly addressed himself to the bishops, and to the Emperor, and

appealed to a council.

The Emperor sent Pretextatus, universally

respected for his virtues and ability, though a pagan, to replace Maximinus as

Prefect of Rome, and to restore peace to the city. But peace was not restored

to the Church till long after, viz., in 381, the Council of Italy examined into

the charges which his enemies persistently maintained against Damasus, when his

accusers were convicted of falsehood and punished; Ursicinus was exiled; the

few Italian bishops who had adopted his party were suspended or deposed; the

fair fame of Damasus was cleared, and his lawful possession of the See of Rome

definitely settled.

Thus some three years passed at Rome, and Jerome had arrived at manhood.

We next find him at Treves, whether with or without an intervening visit to his

paternal home is uncertain. Treves was, at this time, the residence of the

Emperor Valentinian, and the headquarters of his government. It is only

conjecture that the talented young man, who had acquired reputation in the

schools of Rome, may have been sent here with the view of his entering in some

capacity into the service of the State, or taking up the role of an advocate

before the tribunals. Here he continued his literary pursuits; he learnt here

the native Gallic language; he tells us that he copied out St. Hilary for his

friend Rufinus; and he seems to have already taken up with ardour the study of

theology.

It was while at Treves that that crisis in his religious life occurred

which is called his “conversion,” and it was at Rome, probably during a

subsequent visit, that he received (about a.d. 367) the Baptism which had

hitherto been delayed. It was probably also during this second visit that he

became connected with the ascetic party among the patrician ladies of Rome, and

so entered upon a phase of his life and work which forms one of the most

important portions of his subsequent history. In order to understand both this

present incident, and the subsequent history, we must describe the development

of asceticism in the Western Church at this period, which we shall do more

conveniently in a separate chapter.

CHAPTER IV

THE PATRICIAN DEVOTEES OF ROME.

The first great development of Christian asceticism took place in Egypt, in the

time when Athanasius presided over its hundred sees. Antony was

not, indeed, the first who adopted a life of solitude and meditation in the

desert, but he was the first who acquired a great reputation as an example and

teacher of the ascetic life. Multitudes flocked to him, and the deserts began

to be peopled with the cells of the solitaries. Pachomius gathered

a company of ascetics, and organised them into a society, living apart in an

island of the Nile, called Tabenne, and gave them a

rule of life. The sister of Pachomius was induced to embrace a similar life in

the same neighbourhood, and soon found herself at the head of a large community

of nuns, living by her brother’s rule. At the same time that Pachomius

established his order at Tabenne, Macarius took up

his abode in the desert of Scete, near the Libyan frontier; and Ammon

established himself on the Nitrian mountain. Each was

speedily the centre and head of a great following of hermits ; the hermits of

Scete living in solitary cells, those of Nitria grouped

in communities called laura. By the end of the century, the total number of

male anchorites and monks in Egypt was reckoned at 75,000, the females at

27,000. Hilarion, a pupil of Antony’s, introduced monasticism into Syria,

himself occupying, for 50 years, a cell in the desert near Gaza. Thence the

institution spread into Mesopotamia and Armenia.

In the year 341, Athanasius, compelled to flee from the persecution of

the Arian Eastern Emperor, Constantius, came to Rome, where he was safe under

the protection of the orthodox Constans. There came with him two Egyptian

anchorites, Ammon and Isidore, who left the Nitrian desert to attend him in his exile. The illustrious Bishop was received with the

greatest consideration by the Christians of Rome; and his companions, the first

monks who had been seen in the west, excited hardly less interest among them.

It was this visit which seems to have introduced into Rome the ascetic spirit

which flourished in the Egyptian Church. Athanasius had written the life of

Antony, though the father of the Egyptian hermits was still alive. Ammon and

Isidore had known Serapion, the great friend of

Antony, and Macarius, the founder of the communities of Scete. They described

to their rapt auditors, with the vividness of eye-witnesses and of partakers

in it, that life of bodily self-mortification and spiritual exaltation of which

Rome had hitherto only heard rumours. They talked of the monasteries of women;

and of the Church virgins and widows who, still living in their families, had

devoted their lives to God. They preached fervently the nobleness and

blessedness of this spiritual life, and incited their hearers to embrace it.

The teaching fell on ground prepared to receive it

The laws of Rome and the customs of its aristocracy gave large wealth to

the absolute disposal of the female members of wealthy houses, and left them

very independent in the guidance of their own conduct. The patrician ladies of

Rome shared in the prevalent spirit of luxury, frivolity, and dissipation. They

had vast households of eunuchs and slaves, whom they ruled often with feminine

caprice and cruelty. Their toilettes were the most elaborate, costly, and

artificial; they painted their faces, and darkened their eyelids after the

fashion of the East, and wore the finest textures and the costliest jewels.

They rode forth in chariots, or were carried in litters, of gold and ivory, and

spent their time at the baths and in the public places; and too often sought in

intrigues a zest to the indolent luxury of their lives.

Here, we say, was ground prepared to receive the ascetic teaching of

Athanasius and his companions. For it is not only the poor and afflicted and

disappointed and ruined who find this world unsatisfactory, and are led to

set all their hopes on a higher and future life, and to seek refuge meanwhile

in the desert or the cloister. Among the well-born, and wealthy, and luxurious,

are always some nobler spirits who find out the vanity of rank and wealth, and

experience a satiety of sensuous pleasures; who feel the awful mystery of life,

and the craving of an unsatisfied spirit; who learn the lesson of the Scripture,

“Let the brother of high degree rejoice in that he is made low, for as the

flower of the grass he shall pass away”; and out of this class also

the desert and the cloister have always received a proportion of their

inhabitants. The women of the higher class are still more liable to be affected

by this spirit than the men; for the latter have a thousand duties which call

them to healthful exertion, or a thousand active pleasures which banish

thought; but the unmarried women, limited by the conventions of society within

a narrower and more monotonous circle, are left more open to feel the emptiness

of the life they lead, and to brood over the great problems of life and death

and immortality; and to seek in religion some satisfaction for the yearning of

their souls, and some worthy occupation for their days.

It is easy to picture to ourselves the way in which this rise of

asceticism would be received in Rome.

We can imagine the indignation of a great patrician, proud of his

historic race, which had given consuls to Rome and proconsuls to the provinces,

who still lived like a king among his freedmen and slaves, who, albeit rather

from pride than belief, still maintained the worship of the ancient gods of

Rome—we can imagine his indignation when he found the ladies of his house

disregarding the conventions of society, abjuring pride of birth, lavishing

their wealth in building churches and giving alms, offending the old manly

Roman respect for marriage by embracing virginity, and taking some plebeian

priest as the director of their conscience and mode of life.

We can imagine the bitterness of a luxurious and courtly clergy when

some of their number began to teach, by precept and example, that the clergy

ought not to seek presents, and to frequent luxurious tables, and pay their

court to fine ladies, to be self-indulgent in their lives and negligent in

their duties, but ought to be given to fasting and prayer, to rebuke the

fashionable follies and vices of their great patronesses, and to devote

themselves to labour among the poor.

It is easy to imagine the sneer with which the average, easy-going

Christians of a proud, luxurious age would meet what would seem to them an outbreak

of vulgar fanaticism.

And all this old story—fifteen centuries old—has a special interest for

us because the history is repeating itself in our time. We modern English

people, whose temperament is so wonderfully like that old manly, practical,

worldly Roman spirit, suddenly find this ascetic teaching lifting up its voice

among us, and a number of our clergy and the ladies of our families strangely

attracted towards it. We have to open our eyes to the fact that the conventions

of well-to-do society leave our unmarried sisters and daughters in indolent

luxury, with no duties to occupy their minds and no career to look forward to;

and we have to make up our minds whether this disposition towards asceticism

and Church work is a natural craving for occupation influenced by a false

impulse of sentimental antiquarianism, or whether it is really true that the

Holy Spirit calls some persons, at least at certain crises in the history of

the Church, to this exceptional devotion, and that all we have to do is to

recognise and regulate it. We have to open our eyes to the state of religion

among clergy and laity, and to make up our minds whether, in discouraging the

ascetic spirit among our clergy, we should not be crushing the most powerful

instrument for the revival of religion in a careless, worldly state of the

Church, and the most effectual agency for mission work among the civilized

paganisms of the modern world.

It seems to us impossible to deny the force of the example of our Lord

Jesus Christ, who, for our sakes, emptied Himself of the glory which He had

with His Father, and became poor, and went about doing good; and of the

Apostles, who gave themselves up to a life of labours, and dangers, and

hardships, and selfdenials; and of the first

Christians, who sold their possessions and goods, and distributed them to them

that had need; and of all those who “went about in sheepskins and goatskins,

destitute, afflicted, tormented, of whom the world was not worthy”:—

impossible to say that it is mere fanaticism in those who follow these

examples. God does not call all men and women to such a course of life, but we

cannot deny that God seems to call some to it, and that to follow that calling

is not fanaticism, but devotion. The world may still be indignant at the rebuke

conveyed to its worldliness; and the half-believer may still sneer at the

inconceivable fanaticism which really prefers poverty to wealth, humility to

ambition, and self-denial to self-indulgence; but God forbid that the Church

should ever fail to recognise the excellence of a life of entire self-devotion!

It is not our business here to discuss these questions, but, in writing

the history of Jerome’s life, character, and works, it is impossible to omit

them: he who undertakes to be his biographer must make up his own mind upon

them; and probably no one is qualified to be his biographer who has not a

strong sympathy with the general spirit and intention of his ascetic writings,

though with a strong disapprobation of their extravagances and excesses.

Among the noble ladies of Rome there were some who willingly listened to

the exalted teaching of the Egyptian ascetics, and from Jerome himself and other

contemporary writers we have details which bring vividly before us this group

of pious women in the midst of the luxurious society of Rome, and even brief

biographies of several of the most illustrious of them, and of those who, from

time to time, joined their company during the interval of years from the visit

of Athanasius to the point at which we are arrived in the history of Jerome.

Foremost among them was Eutropia, the sister

of Constantine, and great-aunt of the reigning emperor.

Abutera and Sperantia were others, whose names only have been

preserved.

Marcella, the only daughter of Albina, a widow of the most illustrious

ancestry, and of great wealth, Jerome tells us, was the beauty of her time.

Married in early youth, and soon after left a widow, she was sought in marriage

by Cerealis, who was nearly allied to the Imperial

family. But she had imbibed the ascetic spirit from the lips of the Egyptian

exiles. She refused a second marriage, in spite of the entreaties of her

mother; retired to a villa in the environs of Rome, surrounded by large

gardens; took her house for a hermitage and her gardens for the wilderness; and

lived there a life of seclusion and devotion.

Sophronia,

another Christian widow, influenced by Marcella’s example, arranged a little

cell in her own house, instead of retiring from the city.

Marcella then, improving on Sophronia’s suggestion,

consecrated the vast palace of her family on Mount Aventine to pious reunions,

and fitted up an oratory within it This became the centre of a group of pious

ladies, chiefly of the noblest families, widows, wives, and maidens; some

living more or less secluded lives in their own homes; others still living

among their families, and mixing in ordinary society; but all seeking here

support, and sympathy, and guidance in a devout life.

Asella, a widow, sold her

jewels, lived sparingly, and shared her income with the poor.

Furia, a widow of the

noblest family, lived in like manner.

Fabiola, of equal nobility, young, ardent in her passions, who had

divorced one husband, and married a second, became as ardent in her devotion.

Marcellina and Felicitas are two others, of whom we know little beyond their names.

Paula, a matron of the most illustrious ancestry, was already of this

pious circle, though it is not till a later period that her life-long intimacy

with Jerome commenced.

We have many indications of the influence exercised by the ladies of

Rome in the affairs of the Church at this period. It was they who, when

Constantius visited Rome in 357, walked in procession in their richest attire,

through the admiring streets, to ask of the Emperor the return of the banished

Bishop Liberius to the city and See, and obtained

their petition. It was chiefly their lavish donations and legacies, we learn

from Ammianus Marcellinus, which supplied a princely income to the Bishop of

Rome.

Melania, a lady with whom Jerome’s name became publicly connected

during this second visit to Rome, was a young lady of Spanish extraction, but

whose family had been settled in Rome for some generations, and was of the

highest distinction. Married early, at the age of 23 she lost her husband,

and, shortly after, two of her three children. Instead of giving way to grief,

she approached a figure of Christ, with outstretched arms, and a sad smile: “I

am the freer to serve Thee, my Lord,” she said, “ since Thou hast liberated me

from these earthly ties.” After giving her dead a sumptuous funeral, she

announced her intention to depart from Rome; and in spite of the remonstrances

of her family, without making any provision for her surviving child, saying : “God will take care of him better than I,” took ship, and sailed for Egypt. This

incident excited great interest in Rome. The ascetics praised her sublime faith

and devotion; the pagans complained that these ascetic notions violated the

laws of nature, and sapped the bases of society. Jerome’s name was mentioned in

connection with the incident with reprehension; probably he had encouraged her

flight, or had been among its apologists, or both; at least, we here see him in

his early youth, in those relations with the ascetic Roman ladies which were

afterwards renewed, and which entered so largely into the history of his after-life.

CHAPTER V.

JEROME EMBRACES THE ASCETIC LIFE.

A.C. 367- 373.

From Rome Jerome returned to Aquileia. There he found a knot of enthusiasts, chiefly

young men of the higher class of Aquileian society,

whose minds were filled with the ascetic ideas which Jerome had lately imbibed.

Among them were several of the connections and friends of Jerome,—Paulinian his

brother, Bonosus his half-brother, Rufinus, Heliodorus, Chromatius and his brother Eusebius, Jovinus, Innocentius, Nicias, Hylas.

Of this group Rufinus is the most celebrated. We know him as the author

of the Ecclesiastical History which has descended to us under his name, and of

one or two minor works; but we know him best by the place which he occupies in

the life of Jerome. A friendship sprang up between the two young men, which

Jerome spoke of in his writings in such hyperbolical language, and which was

made so widely known by those writings, that the two friends were looked upon

as another Damon and Pythias. Their early friendship terminated in an

acrimonious theological controversy and bitter personal enmity, but we need

not anticipate that part of the history. Paulinian has no history of his own;

from this period we find him almost constantly beside his brother, playing the

part of the fidus Achates—the faithful companion and

trusted helper, whose life is absorbed in the more vigorous life, whose work is

to round off and complete the outlines of the master workman.

Bonosus we already know as the foster-brother of Jerome; it would seem that at the end

of their studentship in Rome he had returned home, while Jerome went to Treves.

Heliodorus was a young man of noble and wealthy Aquileian family, who had been an officer in the army, but had retired from the service

in order to lead a religious life. He will reappear several times in the

subsequent history. Ultimately he was elected Bishop of Altinum in Venetia.

Chromatius,

Eusebius, and Jovinus afterwards entered into holy orders, and in the end

became bishops.

Nicias was at present a deacon of the church of Aquileia; he and Innocentius will shortly reappear in the history.

Hylas was a liberated

slave, enfranchised by Melania before her departure from Rome, who had attached

himself to Jerome.

The genius and enthusiasm of Jerome, and his recent experience of the

ascetic life in the highest ranks of the church at Rome must have given him a

great influence among these Aquileian youths, and it

was probably his force of character which led them at once to put their ascetic

notions into practice. Some of them, including Rufinus, formed themselves into

a religious community in the city itself; one undertook the hardships of a

hermits life in the neighbouring Alps; Bonosus on a

desert island off the neighbouring coast Jerome and his brother retired to

their paternal home at Strido, and there gave

themselves up to the austerities of an ascetic life.

We may be sure that Jerome proclaimed his ascetic notions with

enthusiastic eloquence, and set himself with characteristic vigour to reform

everybody and everything about him. His country neighbours seem to have been

very unimpressible, and the old Bishop Lupicinus seems to have opposed the

novel ideas which his young townsman had brought back from Rome, and. to have

tried to exercise some control over him. This opposition brought to light the

worst side of its great character; opposition enraged him, and this rage sought

vent in unscrupulous violence of language. The young ascetic’s ideas of the

government of the tongue did not prevent him from calling his bishop ignorant,

brutal, wicked, unfit for his post, well matched with the flock he ruled, the

unskilful pilot of a crazy bark. He gives us already an example ’ of one of the

devices by which he habitually sought to throw ridicule on an antagonist, viz.

by fastening a nickname on him ; he dubbed his bishop the Hydra.

Disgusted with the opposition he encountered, he and Paulinian quitted

their home and buried themselves in a solitary place in the country. But his

restless spirit did not long content itself in the solitude ; he returned to

Aquileia—to find that most of his friends had equally failed in their first

experiment in the ascetic life, and, like himself, had returned to town. But

though they had thus failed in their first crude unguided attempt to carry

their idea into practice, they had not abandoned the intention; and when they

found themselves together again, they began to talk about visiting Syria or

Egypt, the great schools of the ascetic life.

At this crisis an incident occurred which gave definite form to the

vague designs floating in their minds. Evagrius, a

priest of Antioch, who had been to Rome on the affairs of the Syrian Church,

was returning through Aquileia, and his acquaintance determined Jerome and some

of his friends to return to Syria with him. Innocentius,

Nicias, Heliodorus, and Hylas accompanied Evagrius on his journey by sea. Jerome preferred to travel

by land. The two parties met again at Caesarea in Cappadocia, where they made

the acquaintance of the great Basil, its bishop, who, by the recent death of

Athanasius, had become the foremost man in the counsels of the orthodox portion

of the Church; and finally they reached Antioch, the great and luxurious

capital of the East, at the close of the year 373.

CHAPTERVI

ANTIOCH AND THE DESERT OF CHALCIS.

a.d. 373-378

Antioch, built by Seleucus, the great city-builder, for the capital of his dominions,

still ranked as the fourth of the cities of the world. The population was

composed of four races: the ifative Syrians; the

Greek colonists; a colony of Jews, whom Seleucus had attracted to his new

capital by the offer of equal privileges with the Greeks; and, lastly, the

Roman official and military classes, with their belongings. It had the

advantage of a well-chosen site, at the point where the river Orontes, after

flowing northwards for 120 miles through the valley of Coele Syria, between

the two parallel ranges of Lebanon and anti-Libanus,

at length finds an opening between the Lebanon and the Taurus ranges, and,

turning sharply westward, at the end of twelve miles more discharges itself

into the sea. The harbour of Seleucia, at the mouth of the river, put the

capital of Asia in easy communication with the Mediterranean, along whose

shores lay all the other great cities of the ancient world. The city lay at the

foot of the pass across Mount Amanus, which formed the great highway between

Asia Minor and Syria; it occupied the mouth of the valley of Coele Syria, the

highway to Palestine; and across the great plain of Antioch, eastward, lay the

caravan road by which was carried the trade of the East.

Enlarged and adorned by successive sovereigns, it had grown into a vast

and magnificent city. As in many of the Eastern cities built by the Greeks, the

backbone of the city was a grand street, four miles long and of considerable

width, with a double colonnade, on each side, of marble columns, forming broad

double aisles, with, perhaps, a narrow space open to the sky, down the middle

of the street The plan was adapted to an Eastern climate and Eastern habits.

The street would form, in fact, a magnificent forum, where, sheltered from the

burning Eastern sun, and in the tempered light of the long covered aisles, the

groups of citizens and visitors would exhibit all day long that variety of

nationality and costume which still makes the bazaars of the Eastern cities so

picturesque. From this central street the other transverse streets of the city

branched at right angles, running down to the river, which bounded it on the

north, and up to the gardens on the slopes of Mount Silpius,

whose rugged heights, and tom, craggy summits, bounded it on the south. There

were the usual temples, and churches, and basilicas, and theatres, and baths. A

temple of Jupiter and a citadel overhung the city from the sides of Silpius. A wall, strengthened at intervals with towers,

enclosed the city, running up the steep sides and along the heights of Silpius, forming, in fact, a chain of castles connected by

a wall, girding, with their rough strength, the graceful and luxurious Syro-Greek metropolis. The reader will call to mind the

special interest of Antioch in the history of the Christian Church. It was the

place where the first Gentile Church was gathered together by the preaching of

certain men of Cyprus and Cyrene, who were scattered abroad from Judea upon the

persecution that arose about Stephen; over which Barnabas was sent by the

Apostles to preside; to which Barnabas brought Saul from Tarsus to help him;

which became the great centre of missionary work to Asia Minor and Greece. Here

the disciples were first called Christians. Over the Church of Antioch,

Ignatius, the disciple of St. John, presided many years, and hence Trajan sent

him to his martyrdom in Rome. This Church was one of the three great

patriarchal Churches of Christendom, the others being Rome and Alexandria; its

bishop was the chief prelate of the Asiatic portion of the Roman empire. In

Rome, we have seen, the pagan temples and their worship were still maintained

in splendour, but in the capital of Asia Christianity had long since gained the

preeminence.

Jerome and his companions had come to Antioch at a critical period of

the history of its Church ; it was distracted by a threefold schism. Meletius,

its bishop, was orthodox, but tolerant; his tolerance had led the Arian party

to concur in his election to the see, but his orthodoxy soon led to his exile

by the Arian Emperor. Then the Arians elected Euzoius,

who was formally installed by the Emperor’s mandate. But the orthodox refused

to recognise Euzoius, and elected Paulinus, who was

consecrated by Lucifer of Cagliari and two Occidental bishops. Each of these

two rival bishops was recognised by his own party. But after a while Meletius

returned from exile and claimed his see. The bishops of the province recognised

Meletius as their legitimate patriarch; but Paulinus refused to give way to

him, on the ground that having been elected by a union of Arians with

Catholics, he was no better than an Arian bishop; and part of the Catholic

Christians of the city adhered to Paulinus, the Arians still recognising only Euzoius.

Evagrius,

the most distinguished person of Paulinus’s party, had been to Rome and

Caesarea, and other of the great sees on this business, and had obtained for

Paulinus the recognition of the Roman See. Jerome and his companions,

therefore, found themselves, on their introduction into the East, enrolled

among the partizans of that section of the Antiochian

Church which the Eastern bishops held to be schismatical.

Jerome appears, however, to have taken no active part in the controversy, but

to have spent his time in diligent study, frequenting the school of

Apollinaris, Bishop of Laodicea, who had a great reputation as a scholar, a

controversialist, and a subtle expositor of the Christian mysteries.

Jerome had spent some time at Antioch, when a chance incident again

changed his plans. One day Evagrius took him with him

on a visit to the town of Maronius, of which he was

the proprietor, some thirty miles from Antioch. While there they paid a visit

to an old man called Malchus, who lived, quite alone,

in a wild spot in the neighbourhood. Jerome was struck with his story, which he

afterwards included among his “Lives of the Fathers of the Desert,” The old

man, years ago, as he was travelling with a caravan of merchants through the

Valley of the Orontes, had been captured by a band of nomad Arabs, who carried

him off into the depths of the desert, and set him to keep their flocks. Lost

in these endless solitudes, and despairing of ever again seeing friends and

country, he was calling upon death to end his misery, when a woman, his

companion in servitude, spoke to him of God, and restored him to patience and

hope. The two lived near each other the lives of Christian solitaries, thus

turning their misfortune to religious profit. At last they succeeded in escaping

together. She entered into a convent of nuns, and he, desiring now no other

life than he had led in the desert, chose out the wild spot where they found

him, and there continued his solitary life. The incident rekindled all Jerome's

old enthusiasm. He resolved to quit the luxurious capital and retire among the

religious of the neighbouring desert of Chalcis.

This desert, situated some fifty miles south-east from Antioch, was

tenanted by monks and solitaries. On its western border were several

monasteries, whose inmates cultivated the neighbouring soil; still further

eastward a crowd of solitaries lived in caves or huts, and raised a scanty

subsistence by their labour; while, among the barren mountains and sands of its

interior, infested by wild beasts and serpents, a few enthusiasts led a life of

terrible endurance, scorched under the Syrian sun in summer, and frozen during

the winter nights by the cold winds from the snow-covered mountains.

Jerome’s influence over his companions induced them to accompany him to

one of the monasteries on the border of the desert. Heliodorus alone declined,

and returned to Aquileia. The unhealthiness of the

climate, and the hardships of the monastic life, told upon the new comers, and

they fell sick. Innocentius died, then Hylas died; Jerome narrowly escaped death. When he

recovered he resolved to quit the convent and take up his abode in one of the

hermitages, among the solitaries of the desert.

The spiritual charms of this life of solitude are set forth by Jerome

himself in a letter which he addressed to Heliodorus—now back in his home in

Aquileia, where he had adopted the fatnily of his

widowed sister—in which he sought to induce his friend to rejoin him in the desert.

“But what am I saying? Am I again thoughtlessly beseeching you? Away

with entreaties and flatteries. Wounded love has a right to be angry. You

despised my entreaties; perhaps you will listen to my reproaches. What are you

doing in your home, O effeminate soldier! Where are the rampart, and the

fosse, and the winter spent in the tented field? Lo, the trumpet sounds from

heaven! Lo, the Imperator, all armed, comes amid the clouds, to fight against

the world! Lo, a two-edged sword proceeds out of His mouth. He mows down

everything which opposes him. And you do not rise from your couch for the

battle. You linger in the shade for fear of the sun’s heat. Your body is clothed

with a tunic instead of a hauberk, your head with a hood instead of a helmet;

the rough sword-hilt chafes the hand softened with idleness! Listen to the

proclamation of your king—‘He who is not with me is against me, and he who

gathers not with me scatters’.

“Remember the day of your enlistment, when buried with Christ in

Baptism, you swore to serve Him, to sacrifice everything even father and mother

—to Him ... Though your little nephew hang about your neck;

though your mother, with rent garments, and head sprinkled with ashes, show

you the breasts at which you were nourished; though your father lie stretched

across the threshold; go forth over your father’s body; go forth, without

shedding a tear, to join the standard of the cross. It is piety in such a

matter to be cruel!

“Ah! I am not insensible to the ties by which you will plead that you

are held back. My breast, too, is not of iron, nor my heart of stone; I was not

begotten of the rocks of Caucasus; the milk I sucked was not that

of Hyrcanian tigresses. I also have gone

through similar trials. I picture to myself your widowed sister hanging about

your neck, and trying to detain you with caresses; and your old nurse, and the

tutor who had all a father’s anxieties over you, telling you they have not long

to live, and begging you not to leave them till they die; and your mother, with

wrinkled face and withered bosom, complaining of your desertion. The love of

God, and the fear of hell, easily break through such bonds as these!

“You Will say the Holy Spirit bids us obey our

parents. Yes; but He teaches also that he who loves them more than Christ,

loses his own soul... ‘My mother and

my brethren’ He says, ‘are they who do the will of my Father which is in

heaven.’ If they believe in Christ, let them encourage you to go forth and

fight in His name; if they do not believe— ‘let the dead bury their dead.’ ...

O desert, blooming with the flowers of Christ. O wilderness, where are shaped

the stones of which the city of the great King is built! O solitude, where men

converse familiarly with Go ! What are you doing among the worldly, O Heliodorus,

you who are greater than all the world? How long shall the cover of roofs weigh

you down; how long shall the prison of the smoking city confine you?

“Do you fear poverty? But Christ calls the poor blessed. Are you

frightened at the prospect of labour? But no athlete is crowned without sweat.

Are you thinking about daily food? But faith fears not hunger. Do you dread to

lay your fasting body on the bare ground? But Christ lies beside you. Do the

tangled locks of a neglected toilet shock you? But your head is Christ Your

skin will grow rough and discoloured without the accustomed bath, but he who is

once washed by Christ needs not to wash again. And, in fine, listen

to the Apostle, who answers all your objections, ‘The sufferings of this

present world are not worthy to be compared with the coming glory which shall

be revealed in us? You are too luxurious, my brother, if you wish

both to enjoy yourself here with the world and afterwards to reign with Christ.

Does the infinite vastness of the wilderness terrify you? Walk in spirit

through the land of Paradise, and while your thoughts are there, you will not

be in the desert.”

In the stem exhortation to Heliodorus to break all natural ties, we

recognise the spirit which might have prompted or defended the flight of

Melania, which did in after years encourage Paula to a like act of stoicism.

In this beautiful—though a little rhetorical—description of the spiritual

joys of the desert, we see one side of the solitary life. In another letter (ad

Eustochium, Ep. 18) Jerome exhibits, on the other hand, his experience of the

hardships of the life, and the temptations of solitude, with a frankness which

lays bare his very soul to our gaze: “Ah! how often, when I dwelt in the

desert, have I, in the midst of that vast solitude which surrounded the

dreadful cell, fancied myself among all the delights of Rome. I sat alone

because my soul was filled with bitterness. My shapeless limbs were clad in a

frightful sack, my squalid skin had taken the hue of an Ethiop’s flesh. I spent

whole days shedding tears and breathing sighs, and when, in spite of myself, I

was overcome with sleep, I let fall, upon the naked earth, a body so emaciated

that the bones scarce held together. I will say nothing of my food or drink,

even the sick had nothing but cold water, and to eat anything cooked was

luxury. Yet I—who for fear of hell, had condemned myself to such a dungeon, the

companion of scorpions and wild beasts—I often imagined myself in the midst of

girls dancing. My face was pallid with fasting, and yet my soul glowed with

desire in my cold body. My flesh had not waited for the destruction of the

whole man, it was dead already, and yet the fires of the passions boiled up

within me. Thus, destitute of all help, I cast myself at the feet of Jesus, I

bathed them with my tears, I wiped them with my hair. I tried to conquer this

rebellious flesh by a week of fasting. I often passed the night and day in

crying, and beating my breast, and ceased not till, God making Himself heard,

peace came back to me. Then I feared to return to my cell as if it had known my

thoughts, and full of anger and severity against myself I plunged alone into

the desert. When I saw some nook of the valleys, some wild spot in the

mountains, some precipice among the rocks, there I made the place of my

prayers, and the prison of my miserable body; and, as God Himself is my

witness, sometimes after having shed floods of tears, after having for a long

time lifted my eyes to heaven, I believed myself transported into the midst of

the choirs of angels; and, filled with confidence and joy, I sang, ‘We will run

after thee, for the odour of thy perfumes’.”

These, however, were only occasional experiences. The ordinary life

Jerome led in his hermitage was of a quiet and regular kind. He had brought his

library with him into the desert, and occupied a great part of his time in

study. His studies were carried on with energy and method. Evagrius,

who visited him from time to time, brought him books, and supplied him with

scribes, who copied books for him, or wrote at his dictation. Neighbouring

monks and solitaries occasionally visited him to discuss questions of

scholarship or points of theology with him. He also kept up a correspondence

with his numerous friends, of which the letter to Heliodorus above quoted, may

be taken for an example.

After a while, his usual studies were interdicted by a dream or vision,

which pronounced them inconsistent with his spiritual vocation. Thus he

himself relates the story: “When years ago I had torn myself from home and

parents, sister and friends, for the kingdom of heaven’s sake, and had taken my

journey for Jerusalem, I could not part with the books which I had

collected at Rome with very great care and labour. And so, unhappy man that I

was, I followed up my fasting by reading Cicero; after a night of watching,

after shedding tears, which the remembrance of my past sins drew from my

inmost soul, I took up Plautus. If sometimes, coming to myself, I began to read

the prophets, their inartistic style repelled me. When my blinded eyes could

not see the light, I thought the fault was in the sun, not in my eyes. While

the old serpent thus deceived me, about the middle of Lent a fever seized me,

and so reduced my strength that my life scarce cleaved to my bones. They began

to prepare for my funeral. My whole body was growing cold, only a little vital

warmth remained in my breast; when suddenly I was caught up in spirit, and

brought before the tribunal of the Judge. So great was the glory of his

presence, and such the brilliancy of the purity of those who surrounded Him,

that I cast myself to the earth, and did not dare to raise my eyes. Being asked

who I was, I answered that I was a Christian. ‘Thou liest’

said the Judge, ‘thou art a Ciceronian, and not a Christian, for where thy

treasure is, there is thy heart also.’ Thereupon, I was silent. He ordered me

to be beaten, but I was tormented more by remorse of conscience than by the

blows, I said to myself ‘Who shall give thee thanks in hell?’. Then I cried,

with tears, ‘Have mercy upon me, O Lord, have mercy upon me.’ My cry was heard

above the sound of the blows. Then they who stood by, gliding to the knees of

the Judge, prayed Him to have mercy on my youth, and He gave me time for

repentance, on pain of more severe punishment if I should read pagan books in

the future. I, who in such a strait, would have promised even greater things,

made oath, and declared by His sacred Name, ‘O Lord, if ever I henceforth

possess profane books or read them, let me be treated as if I had denied Thee.’

After this oath, they let me go, and I returned to the world. To the wonder of

all who stood by, I opened my eyes, shedding such a shower of tears, that my

grief would make even the incredulous believe in my vision. And this was not

mere sleep, or a vain dream, such as often deludes us. The tribunal before

which I lay is witness, that awful sentence which I feared is witness, so may I

never come into a like judgment. I protest that my shoulders were livid, that I

felt the blows after I awoke, and thenceforward I studied divine things with

greater ardour than ever I had studied the things of the world.”