|

READING HALLTHE DOORS OF WISDOM |

|

THE HISTORY OF PYRRHUS OF EPIRUS

|

|

Pyrrhus, King of Epirus,

entered at the very beginning of his life upon the extraordinary series of

romantic adventures which so strikingly marked his career. He became an exile

and a fugitive from his father’s house when he was only two years old, having

been suddenly borne away at that period by the attendants of the household, to

avoid a most imminent personal danger that threatened him. The circumstances

which gave occasion for this extraordinary ereption were as follows:

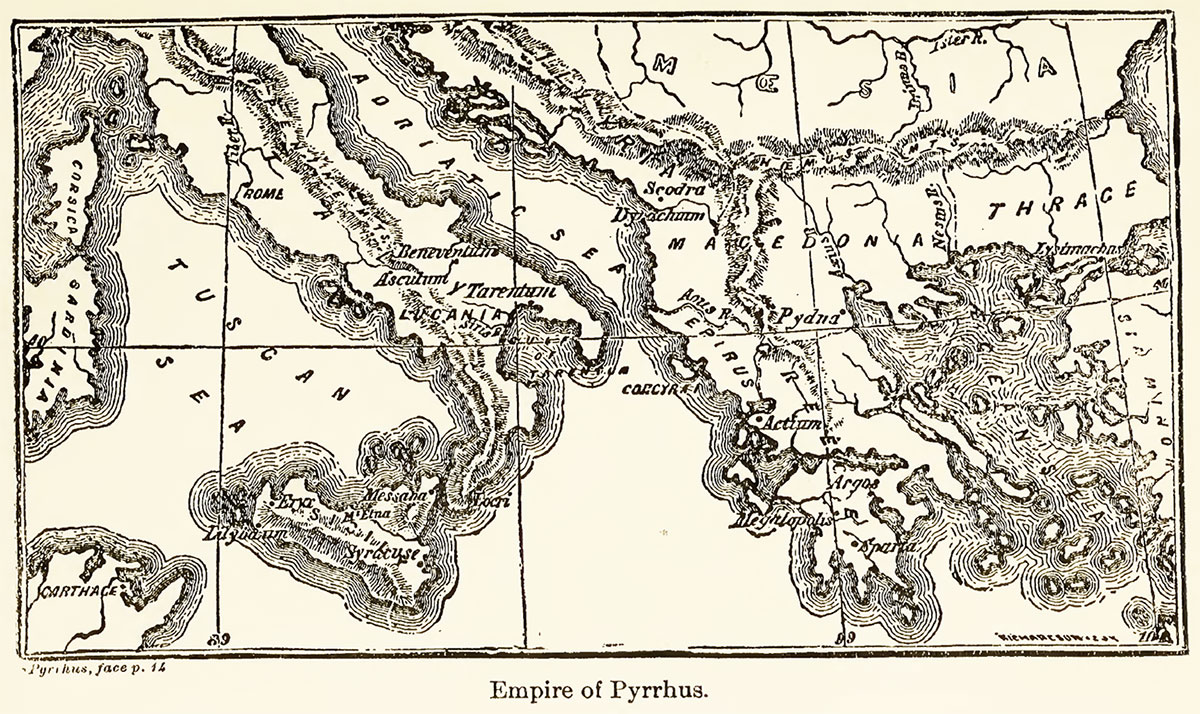

The

country of Epirus, as will be seen by the accompanying map, was situated on the

eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea, and on the southwestern confines of

Macedonia. The kingdom of Epirus was thus very near to, and in some respects

dependent upon, the kingdom of Macedon. In fact, the public affairs of the two

countries, through the personal relations and connections which subsisted from

time to time between the royal families that reigned over them respectively,

were often intimately intermingled, so that there could scarcely be any

important war, or even any great civil dissention in Macedon, which did not

sooner or later draw the king or the people of Epirus to take part in the

dispute, either on one side or on the other. And as it sometimes happened that

in these questions of Macedonian politics the king and the people of Epirus

took opposite sides, the affairs of the great kingdom were often the means of

bringing into the smaller one an infinite degree of trouble and confusion.

The

period of Pyrrhus’s career was immediately subsequent to that of Alexander the

Great, the birth of Pyrrhus having taken place about four years after the death

of Alexander At this time it happened that the relations which subsisted

between the royal families of the two kingdoms were very intimate. This

intimacy arose from an extremely important intermarriage which had taken place

between the two families in the preceding generation—namely, the marriage of

Philip of Macedon with Olympias, the daughter of a king of Epirus. Philip and

Olympias were the father and mother of Alexander the Great. Of course, during

the whole period of the great conqueror’s history, the people of Epirus, as

well as those of Macedon, felt a special interest in his career. They

considered him as a descendant of their own royal line, as well as of that of

Macedon, and so, very naturally, appropriated to themselves some portion of

the glory which he acquired. Olympias, too, who sometimes, after her marriage

with Philip, resided at Epirus, and sometimes at Macedon, maintained an

intimate and close connection, both with her own and with Philip’s family; and

thus, through various results of her agency, as well as through the fame of

Alexander’s exploits, the governments of the two countries were continually

commingled.

It

must not, however, by any means be supposed that the relations which were

established through the influence of Olympias, between the courts of Epirus

and of Macedon, were always of a friendly character. They were, in fact, often

the very reverse. Olympias was a woman of a very passionate and ungovernable

temper, and of a very determined will; and as Philip was himself as impetuous

and as resolute as she, the domestic life of this distinguished pair was a

constant succession of storms. At the commencement of her married life,

Olympias was, of course, generally successful in accomplishing her purpose.

Among other measures, she induced Philip to establish her brother upon the

throne of Epirus, in the place of another prince who was more directly in the

line of succession. As, however, the true heir did not, on this account,

relinquish his claims, two parties were formed in the country, adhering

respectively to the two branches of the family that claimed the throne, and a

division ensued, which, in the end, involved the kingdom of Epirus in protracted

civil wars. While, therefore, Olympias continued to hold an influence over her

husband’s mind, she exercised it in such a way as to open sources of serious

calamity and trouble for her own native land.

After

a time, however, she lost this influence entirely. Her disputes with Philip

ended at length in a bitter and implacable quarrel. Philip married another

woman, named Cleopatra, partly, indeed, as a measure of political alliance,

and partly as an act of hostility and hatred against Olympias, whom he accused

of the most disgraceful crimes. Olympias went home to Epirus in a rage, and

sought refuge in the court of her brother.

Alexander,

her son, was left behind at Macedon at this separation between his father and

mother. He was then about nineteen years of age. He took part with his mother

in the contest. It is true, he remained for a time at the court of Philip after

his mother’s departure, but his mind was in a very irritable and sullen mood;

and at length, on the occasion of a great public festival, an angry conversation

between Alexander and Philip occurred, growing out of some allusions which

were made to Olympias by some of the guests, in the course of which Alexander

openly denounced and defied the king, and then abruptly left the court, and

went off to Epirus to join his mother. Of course the attention of the people of

Epirus was strongly attracted to this quarrel, and they took sides, some with

Philip, and some with Olympias and Alexander.

Not

very long after this Philip was assassinated in the most mysterious and

extraordinary manner. Olympias was generally accused of having been the

instigator of this deed.

There

was no positive evidence of her guilt; nor, on the other hand, had there ever

been in her character and conduct any such indications of the presence of even

the ordinary sentiments of justice and humanity in her heart as could form a

presumption of her innocence. In a word, she was such a woman that it was more

easy and natural, as it seemed, for mankind to believe her guilty than

innocent; and she has accordingly been very generally condemned, though on

very slender evidence, as accessory to the crime.

Of

course, the death of Philip, whether Olympias was the procurer of it or not,

was of the greatest conceivable advantage to her in respect to its effect upon

her position, and upon the promotion of her ambitious schemes. The way was at

once opened again for her return to Macedon. Alexander, her son, succeeded

immediately to the throne. He was very young, and would submit, as she supposed,

very readily to the influence of his mother. This proved, in fact, in some

sense to be true. Alexander, whatever may have been his faults in other

respects, was a very dutiful son. He treated his mother, as long as he lived,

with the utmost consideration and respect, while yet he would not in any sense subject

himself to her authority and influence in his political career. He formed his

own plans, and executed them in his own way; and if there was ever at any time

any dispute or disagreement between him and Olympias in respect to his

measures, she soon learned that he was not to be controlled in these things,

and gave up the struggle. Nor was this a very extraordinary result; for we

often see that a refractory woman, who can not by any

process be made to submit to her husband, is easily and completely managed by a

son.

Things

went on thus tolerably smoothly while Alexander lived. It was only tolerably,

however; for Olympias, though she always continued on friendly terms with

Alexander himself, quarreled incessantly with the commanders and ministers of

state whom he left with her at Macedon while he was absent on his Asiatic

campaigns. These contentions caused no very serious difficulty so long as

Alexander himself was alive to interpose, when occasion required, and settle

the difficulties and disputes which originated in them before they became

unmanageable. Alexander was always adroit enough to do this in a manner that

was respectful and considerate toward his mother, and which yet preserved the

actual administrative power of the kingdom in the hands to which he had intrusted it.

He

thus amused his mother’s mind, and soothed her irritable temper by marks of consideration

and regard, and sustained her in a very dignified and lofty position in the

royal household, while yet he confided to her very little substantial power.

The

officer whom Alexander had left in chief command at Macedon, while absent on

his Asiatic expedition, was Antipater. Antipater was a very venerable man,

then nearly seventy years of age. He had been the principal minister of state

in Macedonia for a long period of time, having served Philip in that capacity

with great fidelity and success for many years before Alexander’s accession.

During the whole term of his public office, he had maintained a most exalted

reputation for wisdom and virtue. Philip placed the most absolute and entire

confidence in him, and often committed the most momentous affairs to his

direction. And yet, notwithstanding the illustrious position which Antipater

thus occupied, and the great influence and control which he exercised in the

public affairs of Macedon, he was simple and unpretending in his manners, and

kind and considerate to all around him, as if he were entirely devoid of all

feelings of personal ambition, and were actuated only by an honest and sincere

devotedness to the cause of those whom he served. Various anecdotes were

related of him in the Macedonian court, which showed the estimation in which he

was held. For example, Philip one day, at a time when placed in circumstances

which required special caution and vigilance on his part, made his appearance

at a late hour in the morning and he apologized for it by saying to the

officers, “I have slept rather late this morning, but then I knew that

Antipater was awake.” Alexander, too, felt the highest respect and veneration

for Antipater’s character. At one time some person expressed surprise that

Antipater did not clothe himself in a purple robe—the badge of nobility and

greatness—as the other great commanders and ministers of state were accustomed

to do. “Those men,” said Alexander, “wear purple on the outside, but Antipater

is purple within.”

The

whole country, in a word, felt so much confidence in the wisdom, the justice,

and the moderation of Antipater, that they submitted very readily to his sway

during the absence of Alexander. Olympias, however, caused him continual

trouble. In the exercise of his regency, he governed the country as he thought

his duty to the people of the realm and to Alexander required, without yielding

at all to the demands or expectations of Olympias. She, consequently, finding

that he was unmanageable, did all in her power to embarrass him in his plans,

and to thwart and circumvent him. She wrote letters continually to Alexander,

complaining incessantly of his conduct, sometimes misrepresenting occurrences

which had actually taken place, and sometimes making accusations wholly

groundless and untrue. Antipater, in the same manner, in his letters to

Alexander, complained of the interference of Olympias, and of the trouble and

embarrassment which her conduct occasioned him. Alexander succeeded for a

season in settling these difficulties more or less perfectly, from time to

time, as they arose; but at last he concluded to make a change in the regency.

Accordingly, on an occasion when a considerable body of new recruits from

Macedon was to be marched into Asia, Alexander ordered Antipater to accompany

them, and, at the same time, he sent home another general named Craterus, in

charge of a body of troops from Asia, whose term of service had expired. His

plan was to retain Antipater in his service in Asia, and to give to Craterus

the government of Macedon, thinking it possible, perhaps, that Craterus might

agree better with Olympias than Antipater had done.

Antipater

was not to leave Macedon until Craterus should arrive there; and while Craterus

was on his journey, Alexander suddenly died. This event changed the whole

aspect of affairs throughout the empire, and led to a series of very important

events, which followed each other in rapid succession, and which were the means

of affecting the conditions and the fortunes of Olympias in a very material

manner. The state of the case was substantially thus. The story forms quite a

complicated plot, which it will require close attention on the part of the

reader clearly to comprehend.

The

question which rose first to the mind of every one, as soon as Alexander’s

death became known, was that of the succession. There was, as it happened, no

member of Alexander’s own family who could be considered as clearly and

unquestionably his heir. At the time of his death he had no child. He had a wife,

however, whose name was Roxana, and a child was born to her a few months after

Alexander’s death. Roxana was the daughter of an Asiatic prince. Alexander had

taken her prisoner, with some other ladies, at a fort on a rock, where her

father had placed her for safety. Roxana was extremely beautiful, and

Alexander, as soon as he saw her, determined to make her his wife. Among the

thousands of captives that he made in his Asiatic campaign, Roxana, it was

said, was the most lovely of all; and as it was only about four years after

her marriage that Alexander died, she was still in the full bloom of youth and

beauty when her son was born.

But

besides this son, born thus a few months after Alexander’s death, there was a

brother of Alexander, or, rather, a half-brother, whose claims to the

succession seemed to be more direct, for he was living at the time that

Alexander died. The name of his brother was Aridaeus. He was imbecile in intellect,

and wholly insignificant as a political personage, except so far as he was by

birth the next heir to Alexander in the Macedonian line. He was not the son of

Olympias, but of another mother, and his imbecility was caused, it was said, by

an attempt of Olympias to poison him in his youth. She was prompted to do this

by her rage and jealousy against his mother, for whose sake Philip had

abandoned her. The poison had ruined the poor child’s intellect, though it had failed

to destroy his life. Alexander, when he succeeded to the throne, adopted

measures to protect Aridaeus from any future attempt which his mother might

make to destroy him, and for this, as well as perhaps for other reasons, took

Aridaeus with him on his Asiatic campaign. Aridaeus and Roxana were both at

Babylon when Alexander died.

Whatever

might be thought of the comparative claims of Aridaeus and of Roxana’s babe in

respect to the inheritance of the Macedonian crown, it was plain that neither

of them was capable of exercising any actual power— Alexander’s son being

incapacitated by his youthfulness, and his brother by his imbecility. The real

power fell immediately into the hands of Alexander’s great generals and counselors

of state. These generals, on consultation with each other, determined not to

decide the question of succession in favor of either of the two heirs, but to

invest the sovereignty of the empire jointly in them both. So they gave to

Aridaeus the name of Philip, and to Roxana’s babe that of Alexander. They made

these two princes jointly the nominal sovereigns, and then proceeded, in their

name, to divide all the actual power among themselves.

In

this division, Egypt, and the African countries adjoining it, were assigned to

a very distinguished general of the name of Ptolemy, who became the founder of

a long line of Egyptian sovereigns, known as the Ptolemaic dynasty—the line

from which, some centuries later, the renowned Cleopatra sprang. Macedon and

Greece, with the other European provinces, were allotted to Antipater and

Craterus—Craterus himself being then on the way to Macedon with the invalid and

disbanded troops whom Alexander had sent home. Craterus was in feeble health

at this time, and was returning to Macedon partly on this account. In fact, he

was not fully able to take the active command of the detachment committed to

him, and Alexander had accordingly sent an officer with him, named

Polysperchon. who was to assist him in the performance of his duties on the

march. This Polysperchon, as will appear in the sequel, took a very important

part in the events which occurred in Macedonia after he and Craterus had

arrived there.

In

addition to these great and important provinces—that of Egypt in Africa, and

Macedon and Greece in Europe—there were various other smaller ones in Asia

Minor and in Syria, which were assigned to different generals and ministers of

state who had been attached to the service of Alexander, and who all now

claimed their several portions in the general distribution of power which took

place after his death. The distribution gave at first a tolerable degree of

satisfaction. It was made in the name of Philip the king, though the personage

who really controlled the arrangement was Perdiccas, the general who was

nearest to the person of Alexander, and highest in rank at the time of the

great conqueror’s decease. In fact, as soon as Alexander died, Perdiccas

assumed the command of the army, and the general direction of affairs. He

intended, as was supposed, to make himself emperor in the place of Alexander.

At first he had strongly urged that Roxana’s child should be declared heir to the

throne, to the exclusion of Aridaeus. His secret motive in this was that by

governing as regent during the long minority of the infant, he might prepare

the way for finally seizing the kingdom himself. The other generals of the

army, however, would not consent to this; they were inclined to insist that

Aridaeus should be king. The army was divided on this question for some days,

and the dispute ran very high. It seemed, in fact, for a time, that there was

no hope that it could be accommodated. There was every indication that a civil

war must ensue—to break out first under the very walls of Babylon. At length,

however, as has already been stated, the question was compromised, and it was

agreed that the crown of Alexander should become the joint inheritance of

Aridaeus and of the infant child, and that Perdiccas should exercise at Babylon

the functions of regent. Of course, when the division of the empire was made,

it was made in the name of Philip; for the child of Roxana, at the time of the

division, was not yet born. But, though made in King Philip’s name, it was

really the work of Perdiccas. His plan, it was supposed, in the assignment of

provinces to the various generals, was to remove them from Babylon, and give them

employment in distant fields, where they would not interfere with him in the

execution of his plans for making himself master of the supreme power.

After

these arrangements had been made, and the affairs of the empire had been tolerably

well settled for the time being by this distribution of power, and Perdiccas

began to consider what ulterior measures he should adopt for the widening and

extending of his power, a question arose which for a season greatly perplexed

him: it was the question of his marriage. Two proposals were made to him—one by

Olympias, and one by Antipater. Each of these personages had a daughter whom

they were desirous that Perdiccas should make his wife. The daughter of Olympias

was named Cleopatra—that of Antipater was Nicaea. Cleopatra was a young widow.

She was residing at this time in Syria. She had been married to a king of

Epirus named Alexander, but was now residing in Sardis, in Asia Minor. Some of

the counselors of Perdiccas represented to him very strongly that a marriage

with her would strengthen his position more than any other alliance that he

could form, as she was the sister of Alexander the Great, and by his marriage

with her he would secure to his side the influence of Olympias and all of

Alexander’s family. Perdiccas so far acceded to these views that he sent a

messenger to Sardis to visit Cleopatra in his name, and to make her a present.

Olympias and Cleopatra accordingly considered the arrangement a settled

affair.

In

the mean time, however, Antipater, who seems to have

been more in earnest in his plans, sent off his daughter Nicaea herself to

Babylon, to be offered directly to Perdiccas there. She arrived at Babylon

after the messenger of Perdiccas had gone to visit Cleopatra. The arrival of

Nicaea brought up very distinctly to the mind of Perdiccas the advantages of an

alliance with Antipater. Olympias, it is true, had a great name, but she

possessed no real power. Antipater, on the other hand, held sway over a

widely-extended region, which comprised some of the most wealthy and populous

countries on the globe. He had a large army under his command, too, consisting

of the bravest and best-disciplined troops in the world; and he himself, though

advanced in age, was a very able and effective commander. In a word, Perdiccas

was persuaded, by these and similar considerations, that the alliance of

Antipater would be more serviceable to him than that of Olympias, and he

accordingly married Nicaea. Olympias, who had always hated Antipater before,

was now, when she found herself thus supplanted by him in her plans for allying

herself with Perdiccas, aroused to the highest pitch of indignation and rage.

Besides

the marriage of Perdiccas, another matrimonial question arose about

this time, which led to a great deal of difficulty. There was a lady of the

royal family of Macedon named Cynane—a daughter of

Philip of Macedon, and half-sister of Alexander the Great—who had a daughter

named Ada. Cynane conceived the design of marrying

her daughter to King Philip, who was now, as well as Roxana and her babe, in

the hands of Perdiccas as their guardian. Cynane set

out from Mace don with her daughter, on the journey to Asia, in order to carry

this arrangement into effect. This was considered as a very bold undertaking

on the part of Cynane and her daughter; for Perdiccas

would, of course, be implacably hostile to any plan for the marriage of Philip,

and especially so to his marrying a princess of the royal family of Macedon. In

fact, as soon as Perdiccas heard of the movement which Cynane was making, he was enraged at the audacity of it, and sent messengers to

intercept Cynane and murder her on the way. This

transaction, however, as soon as it was known, produced a great excitement

throughout the whole of the Macedonian army. The army, in fact, felt so strong

an attachment for every branch and every member of the family of Alexander,

that they would not tolerate any violence or wrong against any one of them.

Perdiccas was quite terrified at the storm which he had raised. He immediately

countermanded the orders which he had given to the assassins; and, to atone

for his error and allay the excitement, he received Ada, when she arrived at

Babylon, with great apparent kindness, and finally consented to the plan of her

being married to Philip. She was accordingly married to him, and the army was

appeased. Ada received at this time the name of Eurydice, and she became

subsequently, under that name, quite renowned in history.

During

the time in which these several transactions were taking place, various intrigues

and contentions were going on among the governors of the different provinces in

Europe and Asia, which, as the results of them did not particularly affect the

affairs of Epirus, we need not here particularly describe.

During

all this period, however, Perdiccas was extending and maturing his arrangements,

and laying his plans for securing the whole empire to himself; while Antipater

and Ptolemy, in Macedon and Egypt, were all the time holding secret

communications with each other, and endeavoring to devise means by which they

might thwart and circumvent him. The quarrel was an example of what very often

occurs in such political systems as the Macedonian empire presented at this

time—namely, a combining of the extremities against the centre.

For some time the efforts of the hostile parties were confined to the maneuvers

and counter-maneuvers which they devised against each other. Antipater was, in

fact, restrained from open hostility against Perdiccas from a regard to his

daughter Nicaea, who as has been already mentioned, was Perdiccas’ wife. At

length, however, under the influence of the increasing hostility which prevailed

between the two families, Perdiccas determined to divorce Nicaea, and marry

Cleopatra after all. As soon as Antipater learned this, he resolved at once

upon open war. The campaign commenced with a double operation. Perdiccas

himself raised an army; and, taking Philip and Eurydice, and also Roxana and

her babe in his train, he marched into Egypt to make war against Ptolemy. At

the same time, Antipater and Craterus, at the head of a large Macedonian force,

passed across the Hellespont into Asia Minor, on their way to attack Perdiccas

in Babylon. Perdiccas sent a large detachment of troops,

under the command of a distinguished general, to meet and encounter Antipater

and Craterus in Asia Minor, while he was himself engaged in the Egyptian

campaign.

The

result of the contest was fatal to the cause of Perdiccas. Antipater advanced

triumphantly through Asia Minor, though in one of the battles which took place

there Craterus was slain. But while Craterus himself fell, his troops were

victorious. Thus the fortunes of war in this quarter went against Perdiccas.

The result of his own operations in Egypt was still more disastrous to him. As

he approached the Egyptian frontier, he found his soldiers very averse to

fighting against Ptolemy, a general whom they had always regarded with extreme

respect and veneration, and who, as was well known, had governed his province

in Egypt with the greatest wisdom, justice, and moderation. Perdiccas treated

this disaffection in a very haughty and domineering manner. He called his

soldiers rebels, and threatened to punish them as such. This aroused their

indignation, and from secret murmurings they proceeded to loud and angry

complaints. Perdiccas was not their king, they said, to lord it over them in

that imperious manner. He was nothing but the tutor of their kings, and they

would not submit to any insolence from him. Perdiccas was soon quite alarmed to

observe the degree of dissatisfaction which he had awakened, and the violence

of the form which it seemed to be assuming. He changed his tone, and attempted

to soothe and conciliate the minds of his men. He at length succeeded so far as

to restore some degree of order and discipline to the army, and in that

condition the expedition entered Egypt.

Perdiccas

crossed one of the branches of the Nile, and then led his army forward to

attack Ptolemy in a strong fortress, where he had intrenched himself with his

troops. The forces of Perdiccas, though much more numerous than those of

Ptolemy, fought with very little spirit; while those of Ptolemy exerted

themselves to the utmost, under the influence of the strong attachment which

they felt for their commander. Perdiccas was beaten in the engagement; and he

was so much weakened by the defeat, that he determined to retreat back across

the river. When the army arrived at the bank of the stream, the troops began to

pass over; but after about half the army had crossed, they found, to their

surprise, that the water, which had been growing gradually deeper all the time,

became impassable. The cause of this deepening of the stream was at first a

great mystery, since the surface of the water, as was evident by marks along

the shore, remained all the time at the same level. It was at length

ascertained that the cause of this extraordinary phenomenon was, that the sands

in the bottom of the river were trampled up by the feet of the men and horses

in crossing, so that the current of the water could wash them away; and such

was the immense number of footsteps made by the successive bodies of troops,

that, by the time the transportation had been half accomplished, the water had

become too deep to be forded. Perdiccas was thus, as it were, caught in a

trap—half his army being on one side of the river, and himself, with the remainder,

on the other.

He

was seriously alarmed at the dangerous situation in which he thus found himself

placed, and immediately resorted to a variety of expedients to remedy the

unexpected difficulty. All his efforts were, however, vain. Finally, as it

seemed imperiously necessary to effect a junction between the two divisions of

his army, he ordered those who had gone over to make an attempt, at all

hazards, to return. They did so; but in the attempt, vast numbers of men got

beyond their depth, and were swept down by the current and drowned. Multitudes

of the bodies, both of the dead and of the dying, were seized and devoured by

the crocodiles which lined the shores of the river below. There were about two

thousand men thus lost in the attempt to recross the stream.

In

all military operations, the criterion of merit, in the opinion of an army, is

success; and, of course, the discontent and disaffection which prevailed in the

camp of Perdiccas broke out anew in consequence of these misfortunes. There

was a general mutiny. The officers themselves took the lead in it, and one

hundred of them went over in a body to Ptolemy’s side, taking with them a

considerable portion of the army; while those that were left remained with

Perdiccas, not to defend, but to destroy him. A troop of horse gathered around

his tent, guarding it on all sides, to prevent the escape of their victim, and

then a certain number of the men rushed in and kill ed him in the midst of his

terror and despair.

Ptolemy

now advanced to the camp of Perdiccas, and was received there with acclamation.

The whole army submitted themselves at once to his command. An arrangement was

made for the return of the army to Babylon, with the kings and their train. Pithon, one of the generals of Perdiccas, took the command

of the army, and the charge of the royal family, on the return. In the mean time, Antipater had passed into Asia, victorious over

the forces that Perdiccas had sent against him. A new congress of generals was

held, and a new distribution of power was made. By the new arrangement,

Antipater was to retain his command in Macedon and Greece, and to have the

custody of the kings. Accordingly, when every thing had thus been settled, Antipater set out on his return to Macedon, with

Philip and Eurydice, and also Roxana and the infant Alexander, in his train.

The venerable soldier—for he was now about eighty years of age—was received in

Macedon, on his return, with universal honor and applause. There were several

considerations, in fact, which conspired to exalt Antipater in the estimation

of his countrymen on this occasion. He had performed a great military exploit

in conducting the expedition into Asia, from which he was now triumphantly

returning. He was bringing back to Macedon, too, the royal family of

Alexander, the representatives of the ancient Macedonian line; and by being

made the custodian of these princes, and regent of the empire in their name, he

had been raised to the most exalted position which the whole world at that

period could afford. The Macedonians received him, accordingly, on his return,

with loud and universal acclamations.

Although Antipater, on his

return to Macedon, came back loaded with honors, and in the full and triumphant

possession of power, his situation was still not without its difficulties. He

had for enemies, in Macedon, two of the most violent and unmanageable women

that ever lived—Olympias and Eurydice—who quarreled with him incessantly, and

who hated each other even more than they hated him.

Olympias

was at this time in Epirus. She remained there, because she did not choose to

put herself under Antipater’s power by residing in Macedon. She succeeded,

however, by her maneuvers and intrigues, in giving Antipater a great deal of

trouble. Her ancient animosity against him had been very much increased and

aggravated by the failure of her plan for marrying her daughter Cleopatra to

Perdiccas, through the advances which Antipater made in behalf of his daughter

Nicaea; and though Nicaea and Perdiccas were now dead, yet the transaction was

an offense which such a woman as Olympias never could forgive.

Eurydice

was a still greater source of annoyance and embarrassment to Antipater than

Olympias herself. She was a woman of very masculine turn of mind, and she had

been brought up by her mother, Cynane, to martial

exercises, such as those to which young men in those days were customarily

trained. She could shoot arrows, and throw the javelin, and ride on horseback

at the head of a troop of armed men. As soon as she was married to Philip she

began at once to assume an air of authority, thinking, apparently, that she

herself, being the wife of the king, was entitled to a much greater share of

the regal authority than the generals, who, as she considered them, were

merely his tutors and guardians, or, at most, only military agents, appointed

to execute his will. During the memorable expedition into Egypt, Perdiccas had found

it very difficult to exercise any control over her; and after the death of

Perdiccas, she assumed a more lofty and imperious tone than ever. She

quarreled incessantly with Pithon, the commander of

the army, on the return from Egypt; and she made the most resolute and

determined opposition to the appointment of Antipater as the custodian of the

persons of the kings.

The

place where the consultation was held, at which this appointment was made, was Triparadeisus, in Syria. This was the place where the

expedition of Antipater, coming from Asia Minor, met the army of Egypt on its

return. As soon as the junction of the two armies was effected, and the grand

council was convened, Eurydice made the most violent opposition to the

proceedings. Antipater reproved her for evincing such turbulence and

insubordination of spirit. This made her more angry than ever; and when at

length Antipater was appointed to the regency, she went out and made a formal

harangue to the army, in which she denounced Antipater in the severest terms,

and loaded him with criminations and reproaches, and endeavored to incite the

soldiers to revolt. Antipater endeavored to defend himself against these

accusations by a calm reply; but the influence which Eurdyice’s tempestuous eloquence exerted on the minds of the soldiery was too much for

him. A very serious riot ensued, which threatened to lead to the most

disastrous results. For a time Antipater’s life was in most imminent danger,

and he was saved only by the interposition of some of the other generals, who

hazarded their own lives to rescue him from the enraged soldiery.

The

excitement of this scene gradually subsided, and, as the generals persisted in

the arrangement which they had made, Eurydice found herself forced to submit

to it. She had, in fact, no real power in her hands except that of making

temporary mischief and disturbance; and, as is usually the case with characters

like hers, when she found that those around her could not be driven from their

ground by her fractiousness and obstinacy, she submitted herself to the

necessity of the case, though in a moody and sullen manner. Such were the

relations which Antipater and Eurydice bore to each other on the return of

Antipater to Macedon.

The

troubles, however, in his government, which Antipater might have reasonably expected

to arise from his connection with Olympias and Eurydice, were destined to a

very short continuance, so far as he personally was concerned; for, not long

after his return to Macedon, he fell sick of a dangerous disease, under which

it was soon evident that the vital principle, at the advanced age to which he

had attained, must soon succumb. In fact, Antipater himself soon gave up all

hopes of recovery, and began at once to make arrangements for the final

surrender of his power.

It

will be recollected that when Craterus came from Asia to Macedon, about the

time of Alexander’s death, he brought with him a general named Polysperchon,

who, though nominally second in command, really had charge of the army on the

march, Craterus himself being at the time an invalid. When, some

time afterward, Antipater and Craterus set out on their expedition to

Asia, in the war against Perdiccas, Polysperchon was left in charge of the

kingdom of Macedon, to govern it as regent until Antipater should return.

Antipater had a son named Cassander, who was a general in his army. Cassander

naturally expected that, during the absence of his father, the kingdom would

be committed to his charge. For some reason or other, however, Antipater had

preferred Polysperchon, and had intrusted the

government to him. Polysperchon had, of course, become acquainted with the

duties of government, and had acquired an extensive knowledge of Macedonian

affairs. He had governed well, too, and the people were accustomed to his sway.

Antipater concluded, therefore, that it would be better to continue Polysperchon

in power after his death, rather than to displace Polysperchon for the sake of

advancing his son Cassander. He therefore made provision for giving to

Cassander a very high command in the army, but he gave Polysperchon the kingdom.

This act, though Cassander himself never forgave it, raised Antipater to a

higher place than ever in the estimation of mankind. They said that he did what

no monarch ever did before; in determining the great question of the

succession, he made the aggrandizement of his own family give place to the welfare

of the realm.

Antipater

on his death-bed, among other councils which he gave to Polysperchon, warned

him very earnestly against the danger of yielding to any woman whatever a share

in the control of public affairs. Woman, he said, was, from her very nature,

the creature of impulse, and was swayed in all her conduct by the emotions and

passions of her heart. She possessed none of the calm, considerate, and

self-controlling principles of wisdom and prudence, so essential for the proper

administration of the affairs of states and nations. These cautions, as

Antipater uttered them, were expressed in general terms, but they were understood

to refer to Olympias and Eurydice, whom it had always been very difficult to

control, and who, of course, when Antipater should be removed from the scene,

might be expected to come forward with a spirit more obtrusive and unmanageable

than ever.

These

councils, however, of the dying king seemed to have had very little effect upon

Polysperchon; for one of the first measures of his government, after Antipater

was dead, was to send to Epirus to invite Olympias to return to Macedon. This

measure was decided upon in a grand council which Polysperchon convened to

deliberate on the state of public affairs as soon as the government came into

his hands. Polysperchon thought that he should greatly strengthen his administration

by enlisting Olympias on his side. She was held in great veneration by all the

people of Macedon; not on account of any personal qualities which she possessed

to entitle her to such regard, but because she was the mother of Alexander.

Polysperchon, therefore, considered it very important to secure her influence,

and the prestige of her .name in his favor. At the same time, while he thus

sought to propitiate Olympias, he neglected Cassander and all the other

members of Antipater’s family. He considered them, doubtless, as rivals and

antagonists, whom he was to keep down by every means in his power.

Cassander,

who was a man of a very bold, determined, and ambitious spirit, remained

quietly in Polysperchon’s court for a little time, watching attentively all

that was done, and revolving silently in his mind the question what course he

himself should pursue. At length he formed a small party of his friends to go

away on a hunting excursion. When he reached a safe distance from the court of

Polysperchon, he called his friends around him, and informed them that he had

resolved not to submit to the usurpation of Polysperchon, who, in assuming the

throne of Macedon, had-seized what rightfully belonged, he said, to him,

Cassander, as his father’s son and heir. He invited his friends to join him in

the enterprise of deposing Polysperchon, and assuming the crown.

He

urged this undertaking upon them with very specious arguments. It was the only course

of safety for them, as well as for him, since they—that is, the friends to whom

Cassander was making these proposals—had all been friends of Antipater; and

Olympias, whom Polysperchon was about to take into his counsels, hated the very

name of Antipater, and would evince, undoubtedly, the most unrelenting

hostility to all whom she should consider as having been his friends. He was confident,

he said, that the Asiatic princes and generals would espouse his cause. They

had been warmly attached to Antipater, and would not willingly see his son and

rightful successor deprived of his legitimate rights. Besides, Philip and

Eurydice would join him. They had everything to fear from Olympias, and would,

of course, oppose the power of Polysperchon, now that he had determined to ally

himself to her.

The

friends of Cassander very readily agreed to his proposal, and the result proved

the truth of his predictions. The Asiatic princes furnished Cassander with

very efficient aid in his attempt to depose his rival. Olympias adhered to

Polysperchon, while Eurydice favored Cassander’s cause. A terrible conflict ensued. It was waged for some time in Greece, and

in other countries more or less remote from Macedon, the advantage in the

combats being sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other. It is not

necessary to detail here the events wliich occurred

in the contest so long as the theatre of war was beyond the frontiers of

Macedon, for the parties with whom we are now particularly dealing were not

directly affected by the conflict until it came nearer home.

It

ought here to be stated that Olympias did not at first accept the invitation to

return to Macedon which Polysperchon sent to her. She hesitated. She consulted

with her friends, and they were not decided in respect to the course which it

would be best for her to pursue. She had made a great many enemies in Macedon

during her former residence there, and she knew well that she would have a

great deal to fear from their hostility in case she should return, and thus put

herself again, as it were, into their power. Then, besides, it was quite

uncertain what course affairs in Macedon would finally take. Antipater had

bequeathed the kingdom to Polysperchon, it was true; but there might be great

doubt whether the people would acquiesce in this decision, and allow the

supreme power to remain quietly in Polysperchon’s hands. She concluded,

therefore, to remain a short time where she was, till she could see how the

case would finally turn. She accordingly continued to reside in Epirus,

keeping up, however, a continual correspondence with Polysperchon in respect

to the measures of his government, and watching the progress of the war between

him and Cassander in Greece, when that war broke out, with the utmost

solicitude and anxiety.

Cassander

proved to be too strong for Polysperchon in Greece. He had obtained large bodies

of troops from his Asiatic allies, and he maneuvered and managed these forces

with so much bravery and skill, that Polysperchon could not dislodge him from

the country. A somewhat curious incident occurred on one occasion during the

campaign, which illustrates the modes of warfare practiced in those days. It

seems that one of the cities of Peloponnesus, named Megalopolis, was on the

side of Cassander, and when Polysperchon sent them a summons to surrender to

him and acknowledge his authority, they withdrew all their property and the

whole of their population within the walls, and bid him defiance. Polysperchon

then advanced and laid siege to the city.

After

fully investing the city and commencing operations on various sides, to occupy

the attention of the garrison, he employed a corps of sappers and miners in

secretly undermining a portion of the wall. The mode of procedure, in

operations like this, was to dig a subterranean passage leading to the

foundations of the wall, and then, as fast as these foundations were removed,

to substitute props to support the superincumbent mass until all was ready for

the springing of the mine. When the excavations were completed, the props were

suddenly pulled away, and the wall would cave in, to the great astonishment of

the besieged, who, if the operation had been skillfully performed, knew nothing

of the danger until the final consummation of it opened suddenly before their

eyes a great breach in their defenses. Polysperchon’s mine was so successful,

that three towers fell into it, with all the wall connecting them. These towers

came down with a terrific crash, the materials of which they had been composed

lying, after the fall, half buried in the ground, a mass of ruins.

The

garrison of the city immediately repaired in great numbers to the spot, to prevent

the ingress of the enemy; while, on the other hand, a strong detachment of

troops rushed forward from the camp of Polysperchon to force their way through

the breach into the city. A very desperate conflict ensued, and while the men

of the city were thus engaged in keeping back the invaders, the women and

children were employed in throwing up a line of intrenchments further within,

to cover the opening which had been made in the wall. The people of the city

gained the victory in the combat. The storming party were driven back, and the

besieged were beginning to congratulate themselves on their escape from the

danger which had threatened them, when they were suddenly terrified beyond

measure by the tidings that the besiegers were arranging a train of elephants

to bring in through the breach, Elephants were often used for war in those days

in Asiatic countries, but they had seldom appeared in Greece. Polysperchon,

however, had a number of them in the train of his army, and the soldiers of

Megalopolis were overwhelmed with consternation at the prospect of being

trampled under foot by these huge beasts, wholly

ignorant as they were of the means of contending against them.

It

happened, however, that there was in the city of Megalopolis at this time a

soldier named Damides, who had served in former years

under Alexander the Great, in Asia. He went to the officers who had command

within the city and offered his aid. “Fear nothing,” said he, “but go on with

your preparations of defense, and leave the elephants to me. I will answer for

them, if you will do as I say.” The officers agreed to follow his instructions.

He immediately caused a great number of sharp iron spikes to be made. These

spikes he set firmly in the ends of short stakes of wood, and then planted the

stakes in the ground all about the intrenchments and in the breach, in such a

manner that the spikes themselves, points upward, protruded from the ground. The

spikes were then concealed from view by covering the ground with straw and

other similar rubbish.

The

consequence of this arrangement was, that when the elephants advanced to enter

the breach, they trod upon these spikes, and the whole column of them was soon

disabled and thrown into confusion. Some of the elephants were wounded so

severely that they fell where they stood, and were unable to rise. Others,

maddened with the pain which they endured, turned back and trampled their own

keepers under foot in their attempts to escape from the scene. The breach, in

short, soon became so choked up with the bodies of beasts and men, that the

assailants were compelled to give up the contest and withdraw. A short time

afterward, Polysperchon raised the siege and abandoned the city altogether.

In

fact, the party of Cassander was in the end triumphant in Greece, and

Polysperchon determined to return to Macedon.

In

the meantime, Olympias had determined to come to Macedon, and aid Polysperchon

in his contest with Cassander. She accordingly left Epirus, and with a small

body of troops, with which her brother Alexander, who was then King of Epirus,

furnished her, went on and joined Polysperchon on his return. Eurydice was

alarmed at this; for, since she considered Olympias as her great political

rival and enemy, she knew very well that there could be no safety for her or

her husband if Olympias should obtain the ascendency in the court of

Polysperchon. She accordingly began to call upon those around her, in the city

where she was then residing, to arm themselves for her defense. They did so,

and a considerable force was thus collected. Eurydice placed herself at the

head of it.

She

sent messengers off to Cassander, urging him to come immediately and join her.

She also sent an embassage to Polysperchon, commanding him, in the name of

Philip the king, to deliver up his army to Cassander. Of course this was only a

form, as she could not have expected that such a command would have been

obeyed; and, accordingly, after having sent off these orders, she placed her- jself at the head of the troops that she had raised, and

marched out to meet Polysperchon on his return, intending, if he would not submit,

to give him battle.

Her

designs, however, were all frustrated in the end in a very unexpected manner.

For when the two armies approached each other, the soldiers who were on

Eurydice’s side, instead of fighting in her cause as she expected, failed her

entirely at the time of trial. For when they saw Olympias, whom they had long

been accustomed almost to adore as the wife of old King Philip, and the mother

of Alexander, and who was now advancing to meet them on her return to Macedon,

splendidly attended, and riding in her chariot, at the head of Polysperchon’s

army, with the air and majesty of a queen, they were so overpowered with the

excitement of the spectacle, that they abandoned Eurydice in a body, and went

over, by common consent, to Polysperchon’s side.

Of

course Eurydice herself and her husband Philip, who was with her at this time,

fell into Polysperchon’s hands as prisoners. Olympias was almost beside herself

with exultation and joy at having her hated rival thus put into her power. She

imprisoned Eurydice and her husband in a dungeon, so small that there was

scarcely room for them to turn themselves in it; and while they were thus

confined, the only attention which the wretched prisoners received was to be

fed, from time to time, with coarse provisions, thrust in to them through a

hole in the wall. Having thus made Eurydice secure, Olympias proceeded to

wreak her vengeance on all the members of the family of Antipater whom she

could get within her power. Cassander, it is true, was beyond 'her reach for

the present; he was gradually advancing through Thessaly into Macedonia, at

the head of a powerful and victorious army. There was another son of

Antipater, however, named Nica nor, who was then in Macedon. Him she seized and

put to death, together with about a hundred of his relatives and friends. In fact,

so violent and insane was her rage against the house of Antipater, that she

opened a tomb where the body of another of his sons had been interred, and

caused the remains to be brought out and thrown into the street. The people

around her began to remonstrate against such atrocities; but these

remonstrances, instead of moderating her rage, only excited it still more. She

sent to the dungeon where her prisoners, Philip and Eurydice, were confined,

and caused Philip to be stabbed to death with daggers; and then, when this

horrid scene was scarcely over, an executioner came in to Eurydice with a dagger,

a rope, and a cup of poison, saying that Olympias sent them to her, that she

might choose herself by what she would die. Eurydice, on receiving this

message, replied, saying, “I pray Heaven that Olympias herself may one day

have the like alternative presented to her.” She then proceeded to tear the

linen dress which she wore into bandages, and to bind up with these bandages

the wounds in the dead body of her husband. This dreadful though useless duty

being performed, she then, rejecting all of the means of self-destruction

which Olympias had offered her, strangled herself by tying tight about her

neck a band which she obtained from her own attire.

Of

course, the tidings of these proceedings were not long in reaching Cassander.

He was at this time in Greece, advancing, however, slowly to the northward,

toward Macedon. In coming from Greece into Thessaly, his route lay through the

celebrated Pass of Thermopylae. He found this pass guarded by a large body of

troops, which had been posted there to oppose his passage. He immediately got

together all the ships, boats, galleys and vessels of every kind which he could

procure, and, embarking his army on board of them, he sailed past the defile,

and landed in Thesally. Thence he marched into

Macedon.

While

Cassander has thus been slowly approaching, Polysperchon and Olympias had been

very vigorously employed in making preparations to receive him. Olympias, with

Roxana and the young Alexander, who was now about five years old, in her train,

traveled to and fro among the cities of Macedonia,

summoning the people to arms, enlisting all who would enter her service, and

collecting money and military stores. She also sent to Epirus, to Eakides the

king, the father of Pyrrhus, imploring him to come to her aid with all the

force he could bring. Polysperchon, too, though separate from Olympias, made

every effort to strengthen himself against his coming enemy. Things were in

this state when Cassander entered Macedon.

Cassander

immediately divided his troops into two distinct bodies, and sending one, under

the command of an able general, to attack Polysperchon, he himself went in pursuit

of Olympias. Olympias retreated before him, until at length she reached the

city of Pydna, a city situated in the southeastern part of Macedon, on the shore

of the Aegean Sea. She knew that the force under her command was not sufficient

to enable her to offer her enemy battle, and she accordingly went into the

city, and fortified herself there. Cassander advanced immediately to the place,

and, finding the city too strongly fortified to be carried by assault, he

surrounded it with his army, and invested it closely both by land and sea. .

The

city was not well provided for a siege, and the people within very soon began

to suffer for want of provisions. Olympias, however, urged them to hold out,

representing to them that she had sent to Epirus for assistance, and that Eakides,

the king, was already on his way, with a large force, to succor her. This was

very true; but, unfortunately for Olympias, Cassander was aware of this fact as

well as she, and, instead of waiting for the troops of Eakides to come and

attack him, he had sent a large armed force to the confines between Epirus and

Macedon, to intercept these expected allies in the passes of the mountains.

This movement was successful. The army of 2Eacides found, when they reached the

frontier, that the passages leading into Macedonia were all blocked up by the

troops of the enemy. They made some ineffectual attempts to break through; and

then the leading officers of the army, who had never been really willing to

embark in the war, revolted against Eakides, and returned home. And as, in the

case of deeds of violence and revolution, it is always safest to go through

and finish the work when it is once begun, they deposed 2Eacides entirely, and

raised the other branch of the royal family to the throne in his stead. It was

on this occasion that the infant Pyrrhus was seized and carried away by his

friends, to save his life, as mentioned in the opening paragraphs of this

history. The particulars of this revolution, and of the flight of Pyrrhus, will

be given more fully in the next chapter. It is sufficient here to say, that

the attempt of Eakides to come to the rescue of Olympias in her peril wholly

failed, and there was nothing now left but the wall of the city to defend her

from her terrible foe.

In

the meantime, the distress in the city for want of food had become horrible.

Olympias herself, with Roxana and the boy, and the other ladies of the court,

lived on the flesh of horses. The soldiers devoured the bodies of their

comrades as they were slain upon the wall. They fed the elephants, it was said,

on saw-dust. The soldiers and the people of the city, who found this state of

things intolerable, deserted continually to Cassander, letting themselves

down by stealth in the night from the wall. Still Olympias would not surrender;

there was one more hope remaining for her. She contrived to dispatch a messenger

to Polysperchon with a letter, asking him to send a galley round into the

harbor at a certain time in the night, in order that she might get on board of

it, and thus escape. Cassander intercepted this messenger. After reading the

letter, he returned it to the messenger again, and directed him to go on and

deliver it. The messenger did so, and Polysperchon sent the galley. Cassander,

of course, watched for it, and seized it himself when it came. The last hope of

the unhappy Olympias was thus extinguished, and she opened the gates and gave

herself up to Cassander. The whole country immediately afterward fell into Cassander’s hands.

The

friends of the family of Antipater were now clamorous in their demands that

Olympias should be brought to punishment for having so atrociously murdered

the sons and relatives of Antipater while she was in power. Olympias professed

herself willing to be tried, and appealed to the Macedonian senate to be her

judges. She relied on the ascendency which she had so long exercised over the

minds of the Macedonians, and did not believe that they would condemn her.

Cassander himself feared that they would not; and although he was unwilling to

murder her while she was a defenseless prisoner in his hands, he determined

that she should die. He recommended to her secretly not to take the hazard of

a trial, but to make her escape and go to Athens, and offered to give her an

opportunity to do so. He intended, it was said, if she made the attempt, to

intercept and slay her on the way as a fugitive from justice. She refused to

accede to this proposal, suspecting, perhaps, Cassander’s treachery in making it. Cassander then sent a band of two hundred soldiers to

put her to death.

These

soldiers, when they came into the prison, were so impressed by the presence of

the queen, to whom, in former years, they had been accustomed to look up with

so much awe, that they shrank back from their duty, and for a time it seemed

that no one would strike the blow. At length, however, some among the number,

who were relatives of those that Olympias had murdered, succeeding in nerving

their arms with the resolution of revenge, fell upon her and killed her with

their swords.

As

for Roxana and the boy, Cassander kept them close prisoners for many yearjs; and finally, feeling more and more that his possession

of the throne of Alexander was constantly endangered by the existence of a son

of Alexander, caused them to be assassinated too.

CHAPTER

III.

EARLY

LIFE OF PYRRHUS.

In the two preceding chapters we

have related that portion of the history of Macedonia which it is necessary to

understand in order rightly to appreciate the nature of the difficulties in

which the royal family of Epirus was involved at the time when Pyrrhus first appeared

upon the stage. The sources of these difficulties were two: first, the

uncertainty of the line of succession, there being two branches of the royal

family, each claiming the throne, which state of things was produced, in a

great measure, by the interposition of Olympias in the affairs of Epirus some

years before; and, secondly, the act of Olympias in inducing Eakides to come to

Macedonia, to embark in her quarrel against Cassander there. Of course, since

there were two lines of princes, both claiming the throne, no sovereign of

either line could hold any thing more than a divided

empire over the hearts of his subjects; and consequently, when Eakides left the

kingdom to fight the battles of Olympias in Macedon, it was comparatively easy

for the party opposed to him to effect a revolution and raise their own prince

to the throne.

The

prince whom Olympias had originally made king of Epirus, to the exclusion of

the claimant belonging to the other branch of the family, was her own brother.

His name was Alexander. He was the son of Neoptolemus. The rival branch of the

family were the children of Arymbas, the brother of

Neoptolemus. This Alexander flourished at the same time as Alexander the Great,

and in his character very much resembled his distinguished namesake. He

commenced a career of conquest in Italy at the same time that his nephew

embarked in his in Asia, and commenced it, too, under very similar circumstances.

One went to the East, and another to the West, each determined to make himself

master of the world. The Alexander of Macedon succeeded. The Alexander of

Epirus failed. The one acquired, consequently, universal and perpetual renown,

while the memory of the other has been almost entirely neglected and

forgotten.

One

reason, unquestionably, for the difference in these results was the difference

in the character of the enemies respectively against whom the two adventurers

had to contend. Alexander of Epirus went westward into Italy, where he had to

encounter the soldiery of the Romans—a soldiery of the most rugged,

determined, and indomitable character. Alexander of Macedon, on the other hand,

went to the East, where he found only Asiatic races to contend with, whose

troops, though countless in numbers and magnificently appointed in respect to

all the purposes of parade and display, were yet enervated with luxury, and

wholly unable to stand against any energetic and determined foe. In fact, Alexander

of Epirus used to say that the reason why his nephew, Alexander of Macedon, had

succeeded, while he himself had failed, was because he himself had invaded

countries peopled by men, while the Macedonian, in his Asiatic campaign, had encountered

only women.

However

this may be, the campaign of Alexander of Epirus in Italy had a very disastrous

termination. The occasion of his going there was a request which he had

received from the inhabitants of Tarentum that he would come over and assist

them in a war in which they were engaged with some neighboring tribes.

Tarentum was a city situated toward the western shore of Italy. It was at the

head of the deep bay called the Gulf of Tarentum, which bay occupies the hollow

of the foot that the form of Italy presents to the eye as seen upon a map.*

Tarentum was, accordingly, across the Adriatic Sea from Epirus. The distance

was about two hundred miles. By taking a southerly route, and going up the

Gulf of Tarentum, this distance might be traversed wholly by sea. A little to

the north the Adriatic is narrow, the passage there being only about fifty

miles across. To an expedition, however, taking this course, there would

remain, after arriving on the Italian shore, fifty miles or more to be accomplished

by land in order to reach Tarentum.

Before

deciding to comply with the request of the Tarentines that he would come to

their aid, Alexander sent to a celebrated oracle in Epirus, called the oracle

of Dodona, to inquire whether it would be safe for him to undertake the

expedition. To his inquiries the oracle gave him this for an answer:

“The

waters of Acheron will be the cause of your death, and Pandosia is the place where you will die.”

Alexander

was greatly rejoiced at receiving this answer. Acheron was a stream of Epirus,

and Pandosia was a town upon the banks of it. He

understood the response to mean that he was fated to die quietly in his own

country at some future period, probably a remote one, and that there was no

danger in his undertaking the expedition to Which he had been called. He

accordingly set sail from Epirus, and landed in Italy; and there, believing

that he was fated to die in Epirus, and not in Italy, he fought in every battle

with the most desperate and reckless bravery, and achieved prodigies of valor.

The possibility that there might be an Acheron and a Pandosia in Italy, as well as in Epirus, did not occur to his mind.

For

a time he was very successful in his career. He fought battles, gained

victories, conquered cities, and established his dominion over quite an

extended region. In order to hold what he had gained, he sent over a great

number of hostages to Epirus, to be kept there as security for the continued

submission of those whom he had subdued. These hostages consisted chiefly, as

was usual in such cases, of children. At length, in the course of the war, an

occasion arose in which it was necessary, for the protection of his troops, to

encamp them on three hills which were situated very near to each other. These

hills were separated by low interval lands and a small stream; but at the time

when Alexander established his encampment, the stream constituted no

impediment to free intercommunication between the different divisions of his

army. There came on, however, a powerful rain; the stream overflowed its

banks; the intervals were inundated. This enabled the enemy to attack two of

Alexander’s encampments, while it was utterly impossible for Alexander himself

to render them any aid. The enemy made the attack, and were successful in it.

The two camps were broken up, and the troops stationed in them were put to

flight. Those that remained with Alexander, becoming discouraged by the

hopeless condition in which they found themselves placed, mutinied, and sent

to the camp of the enemy, offering to deliver up Alexander to them, dead or

alive, as they should choose, on condition that they themselves might be

allowed to return to their native land in peace. This proposal was accepted;

but, before it was put in execution, Alexander, having discovered the plot,

placed himself at the head of a determined and desperate band of followers,

broke through the ranks of the enemies that surrounded him, and made his escape

to a neighboring wood. From this wood he took a route which led him to a

river, intending to pass the river by a bridge which he expected to find there,

and then to destroy the bridge as soon as he had crossed it, so as to prevent

his enemies from following him. By this means he hoped to make his way to some

place of safety. He found, on arriving at the brink of the stream, that the

bridge had been carried away by the inundation. He, however, pressed forward

into the water on horseback, intending to ford the stream. The torrent was

wild, and the danger was imminent, but Alexander pressed on. At length one of

the attendants, seeing his master in imminent danger of being drowned,

exclaimed aloud, “This cursed river! well is it named Acheron. ” The word

Acheron, in the original language, signifies River of Sorrow.

By

this exclamation Alexander learned, for the first time, that the river he was

crossing bore the same name with the one in Epirus, which he supposed had been

referred to in the warning of the oracle. He was at once overwhelmed with

consternation. He did not know whether to go forward or to return. The moment

of indecision was suddenly ended by a loud outcry from his attendants, giving

the alarm that the traitors were close upon him. Alexander then pushed forward

across the water. He succeeded in gaining the bank; but as soon as he did so, a

dart from one of his enemies reached him and killed him on the spot. His

lifeless body fell back into the river, and was floated down the stream, until

at length it reached the camp of the enemy, which happened to be on the bank of

the stream below. Here it was drawn out of the water, and subjected to every

possible indignity. The soldiers cut the body in two, and, sending one part to

one of the cities as a trophy of their victory, they set up the other part in

the camp as a target for the soldiers to shoot at with darts and javelins.

At

length a woman came into the camp, and, with earnest entreaties and many tears,

begged the soldiers to give the mutilated corpse to her. Her object in wishing

to obtain possession of it was, that she might send it home to Epirus, to the

family of Alexander, and buy with it the liberty of her husband and her

children, who were among the hostages which had been sent there. The soldiers

acceded to this request, and the parts of the body having been brought together

again, were taken to Epirus, and delivered to Olympias, by whom the remains

were honorably interred. We must presume that the woman who sent them obtained

the expected reward, in the return of her husband and children, though of this

we are not expressly informed.

Of

course, the disastrous result of this most unfortunate expedition had the

effect, in Epirus, of diminishing very much the popularity and the strength of

that branch of the royal family—namely, the line of Neoptolemus—to which

Alexander had belonged. Accordingly, instead of being succeeded by one of his

brothers, Eakides, the father of Pyrrhus, who was the representative of the

other line, was permitted quietly to assume the crown. It might have been

expected that Olympias would have opposed his accession, as she was herself a

princess of the rival line. She did not, however, do so. On the contrary, she

gave him her support, and allied herself to him very closely; and he, on his

part, became in subsequent years one of her most devoted adherents and friends.

When

Olympias was shut up in Pydna by the army of Cassander, as was related in the last

chapter, and sent for Eakides to come to her aid, he immediately raised an army

and marched to the frontier. He found the passes in the mountains which led

from Epirus to Macedonia all strongly guarded, but he still determined to force

his way through. He soon, however, began to observe marks of discontent and

dissatisfaction among the officers of his army. These indications increased,

until at length the disaffection broke out into open mutiny, as stated in the

last chapter. 2Eacides then called his forces together, and gave orders that

all who were unwilling to follow him into Macedon should be allowed freely to

return. He did not wish, he said, that any should accompany him on such an

expedition excepting those who went of their own free will. A considerable part

of the army then returned, but, instead of repairing peaceably to their homes,

they raised a general insurrection in Epirus, and brought the family of

Neoptolemus again to the throne. A solemn decree of the state was passed,

declaring that Eakides, in withdrawing from the kingdom, had forfeited his

crown, and banishing him forever from the country. And as this revolution was

intended to operate, not merely against Eakides personally, but against the

branch of the royal family to which he belonged, the new government deemed it

necessary, in order to finish their work and make it sure, that many of his

relatives and friends, and especially his infant son and heir, should die.

Several of the members of Eakides’ family were accordingly killed, though the

attendants in charge succeeded in saving the life of the child by a sudden

flight.

The

escape was effected by the instrumentality of two of the officers of Eakides’

household, named Androclides and Angelus. These men,

as soon as the alarm was given, hurried the babe away, with only such nurses

and other attendants as it was necessary to take with them. The child was still unweaned; and though those in charge made the number

of attendants as small as possible, still the party were necessarily of such a

character as to forbid any great rapidity of flight. A troop was sent in

pursuit of them, and soon began to draw near. When Androclides found that his party would be overtaken by the troop, he committed the child to

the care of three young men, bidding them to ride on with him, at their utmost

speed, to a certain town in Macedon, called Megarae,

where they thought he would be safe; and then he himself, and the rest of his

company, turned back to meet the pursuers. They succeeded, partly by their

representations and entreaties, and partly by such resistance and obstruction

as it was in their power to make, in stopping the soldiers where they were. At

length, having, though with some difficulty, succeeded in getting away from

the soldiers, Androclides and Angelus rode on by

secret ways till they overtook the three young men. They now began to think

that the danger was over. At length, a little after sunset, they approached the

town of Megarae. There was a river just before the

town, which looked too rough and dreadful to be crossed. The party, however,

advanced to the brink, and attempted to ford the stream, but they found it imposssible. It was growing dark; the water of the river,

having been swelled by rains, was very high and boisterous, and they found

that they could not get over. At length they saw some of the people of the town

coming down to the bank on the opposite side. They were in hopes that these

people could render them some assistance in crossing the stream, and they began

to call out to them for this purpose; but the stream ran so rapidly, and the

roaring of the torrent was so great, that they could not make themselves heard.

The distance was very inconsiderable, for the stream was not wide; but, though