|

CHAPTER XIX.

REVIVAL OF THE IRISH HARP

The Granard Festivals.

The Belfast Harp Meeting. Edward Bunting. Arthur O'Neill. The

Belfast Harp Society. The Dublin Harp Society. Revival of the

Belfast Harp Society. The Irish Harp as a fashion. The Drogheda

Harp Society. The modern Irish Harp. Method of tuning.

Between the years 1750

and 1780 the Irish harp, owing to causes which it is unnecessary

to mention, was becoming moribund. At length, through the

generosity of an Irish exile at Copenhagen, James Dungan, a harp

festival was organised at Granard, Co. Longford, in 1781. Seven

harpers competed, including a lady, Rose Mooney. At the second Granard

Festival, on March 2nd, 1782, nine candidates presented themselves—that

is to say, the seven of the previous year, and two others, Catherine

Martin and Edward McDermot Roe. Eleven harpers performed at the

third meeting, in 1783, at which Dungan himself was

present, and a similar number competed in 1784.

The fifth and last Granard

Festival came off in August, 1785, attended by upwards of a thousand

persons. Premiums of seven, five, three, and two guineas were

offered. Arthur O'Neill, in his account of these harp meetings,

adds :—"In consequence of the harpers who obtained no premiums

having been neglected on the former occasions, I hinted a subscription,

which was well received and performed [sic]; and, indeed, on distributing

the collection, their proportions exceeded our premiums."

Six years later, the great

Belfast Harp Meeting was held in the Old Exchange, on July 11th,

12th, 13th, and 14th, 1792. Ten harpers competed—namely, Denis

Hampson, Arthur O'Neill, Charles Fanning, Daniel Black, Charles

Byrne, Hugh Higgins, Patrick Quin, William Carr, Rose Mooney,

and James Duncan. The first prize (ten guineas) was awarded to

Charles Fanning, for his playing of Au Cuilfhionn (The Coolin);

whilst Arthur O'Neill got second prize (eight guineas), for "The

Green Woods of Truagh" and "Madame Crofton."

In all, some

forty tunes (thirty of which were the compositions of O'Carolan)

were played by the ten harpers during the four days'

festival, and Edward Bunting, assistant organist to

William Ware, of St. Anne's Church, Belfast, was commissioned

to noted down the airs.

This was the origin of Bunting's first volume of ancient Irish

music, published in 1796, towards the publication of which the

Belfast Library (still flourishing) contributed a sum of £50.

Arthur O'Neill deserves

more than a passing notice as the last of the old school of Irish

harp-players. Born near Dungannon, Co.

Tyrone, in 1726, O'Neill was blind from the age of eight, and

was, in 1742, placed under the

tuition of Owen Keenan, and, subsequently, of Hugh O'Neill, with

a view of becoming a professional harper. Early in 1750 he began

his career as a wandering minstrel, and during ten years made

a circuit of Ireland, visiting the chief families in each county.

As an incident of his visit to the hospitable mansion of Mr. James

Irwin, of Streams-town, in 1759, he thus writes in his Memoirs:—

"This gentleman [Mr. Irwin]

had an ample fortune, and was passionately fond of music. He had

four sons and three daughters, who were all proficients; no instrument

was unknown to them. There was at one lime a meeting in his house

of forty-six musicians, who played in the following order:—The

three Miss Irwins at the piano [harpsichord];

myself at harp; six gentlemen, flutes; two gentlemen, violoncellos;

ten common pipers; twenty gentlemen, fiddlers; four gentlemen,

clarionets."

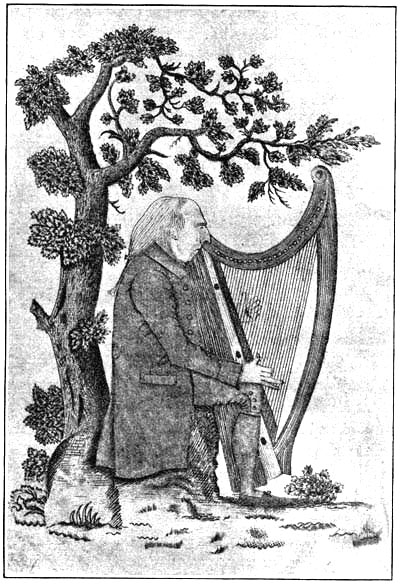

ARTHUR O'NEILL, FIRST

MASTER OF THE BELFAST HARP SOCIETY. |

|

O'Neill played on the "O'Brien"

harp in Limerick in 1760. He ceased his wanderings in 1778, and

became harp teacher to the family of Dr. James M'Donnell, in Belfast.

His ancestral home at Glenarb, near Caledon, was burned during

the troubles of '98, and he resumed his avocation of minstrel.

From 1808 to 1813 he was teacher of the harp to the Belfast Harp

Society, and he died at Maydown, Co. Armagh, on October 29th,

1816, aged ninety years. His harp is now in the museum of the

Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society.

The accompanying illustration

is a reproduction of that by Thomas Smyth of Belfast, similar

to that which was specially drawn for Bunting's second volume

(1809).

On March 17th

(St. Patrick's Day), 1808, the Belfast Harp Society was formally

inaugurated at Linn's Hotel, Castle Street, the subscribers cherishing

the idea that such an institution would perpetuate the old school

of harpers so praised in the twelfth century by Cambrensis. The

Society original subscribers numbered 191, and the total annual

subscriptions amounted to £300. Arthur O'Neill was appointed first teacher,

and the classes opened with eight boy-pupils and a girl. Harps

were supplied by White, M'Clenaghan, and M'Cabe, of Belfast, at

a cost of ten guineas each. All went well for three years, but

in 1812 the society was in difficulties, and in 1813 it collapsed,

having expended during the six years of its existence about £955.

In Dublin, a revival of

the Irish harp began in 1803, in which year John Egan started

a harp factory. In 1805 Lady Morgan1 purchased an Irish harp,

and this set the fashion in Dublin, which extended to Dublin Castle

and Viceregal circles.In fact, from 1805 to 1845, the pianoforte

was temporarily obscured by the Irish harp, and many of Eblana's

fair daughters affected a weakness for Erin's national instrument.

The Dublin Harp Society—due to the exertions of the unfortunate

John Bernard Trotter, ex-secretary to Charles James Fox—was inaugurated

on July 13th, 1809, and Patrick Quin, the famous blind harper

of Portadown, was appointed teacher. The list of subscribers included

"noblemen, gentlemen, and professors," and the names of Sir Walter

Scott, Sir Henry Wilkinson, Tom Moore, Joseph Cooper Walker, and other

literary personages appear as generous donors. Trotter himself

subsidised the society to the extent of £200, and the Bishop of

Kildare gave his house at Glasnevin for an academy. The only tangible

work accomplished by this society was the giving of a Carolan

Commemoration at the Private Theatre, Fishamble Street, on September

20th, 1809, which was repeated on the 27th of the same month.

These performances realised £215, and Sir John Stevenson, Logier,

Willman, Dr. Spray, Tom Cooke, Miss Cheese, and Dr. Weyman assisted,

with harp solos by Patrick Quin.

The Rules and Regulations

of the Dublin Harp Society were printed in 1810, at which date

Patrick Quin had four blind boys under instruction. Alas! the

society became defunct in 1812, and poor Trotter died a pauper,

in Cork, in 1818.

The Belfast

Harp Society was re-established in 1819, as the result

of a meeting held to administer a fund of £1200, forwarded

by some Irish exiles in India, "to revive the harp

and ancient music of Ireland". Classes were

again started, and a small number of harps

was procured, the pupils being selected from

"the blind and the helpless."

This benevolent scheme

lingered on for almost twenty years, regarding which

Petrie writes as follows:— "The effort of the people of the North

to perpetuate the existence of the harp in Ireland, by trying

to give a harper's skill to a number of poor blind boys, was at

once a benevolent and a patriotic one; but it was a delusion.

The harp at the time was virtually dead, and such effort could

give it for a while only a sort of galvanised vitality. The selection

of blind boys, without any greater regard for their musical capacities

than the possession of the organ of hearing, for a calling which

doomed them to a wandering life, was not a well-considered benevolence,

and should never have had any fair hope of success."

In 1809 Irish harps were

purchased by many titled dames in Ireland, and the fashion survived

till 1835. John Egan's harps were in much request, as is evident from the following

extract of a letter written by the Marchioness

of Abercorn to Lady Morgan:—"Your

harp is arrived, and, for the honour of Ireland, I must tell you,

it is very much admired and quite beautiful. Lady Aberdeen played

on it for an hour, and thought it very good, almost as good as

a French harp. . . . Pray tell poor Egan I shall show it off to

the best advantage, and I sincerely hope he will have many orders

in consequence."

In 1822 Charles Egan published

a Harp Primer, which was reprinted in 1829; and he also

issued, in 1827, the Royal Harp Director. So extensive

was his trade in the matter of Irish harps that he had two shops

in Dublin. However, after the year 1835, the "fad" went out, and

Egan's Irish harp factory disappeared.

A new Harp

Society was established at Drogheda on January 15th, 1842, owing

to the patriotic zeal of the Rev. T. V. Burke, a Dominican friar

of that town. The first year's report showed a class of fifteen

pupils, with Hugh Fraser as teacher. Twelve new

harps were procured, Drogheda manufacture, at a cost of three

guineas each.

From the printed

programme of the first public concert of the Drogheda Harp Society,

on Monday, February 24th, 1844, it appears that Mr. Fraser had

taught sixteen pupils. At this concert the harpers were assisted

by Miss Flynn, Mr. Halpin, Mr. Dowdall, and Mr. M'Entaggart. The

second concert was given in 1848, after which the society collapsed.

Then came the famine, and the gradual disappearance of the old

harpers. After this, the Irish harp was neglected till the Irish Ireland Movement,

inaugurated by William Rooney and the United Irishman,

and fostered by the Gaelic League, Celtic Literary Society, and

kindred associations, again galvanised the national instrument

into life. From 1897 the Oireachtas and Feis Ceoil have had harp

competitions, but the feeling is irresistibly borne on the impartial

observer that, save as a matter of sentiment, the Irish harp has

been ousted in popular circles by the pianoforte and violin. All

the same, there is something so essentially characteristic about

the Irish harp that, as a national instrument, it must be kept

alive.

Perhaps the best proof

of the demand for the Irish harp is that there are two harp factories

in Belfast, and the instruments are really very fine, especially those made by

Mr. James M'Fall.

The

compass of the Irish harp is about four octaves, from

C to G in alt, and the strings are of catgut—the C's

being coloured red, and the F's blue. It

is tuned by fifths and octaves, and the < performers

can prove the tuning by other consonant intervals. Though

mostly tuned in the key of C, some harpists prefer that

of E flat. Each string can be raised a semitone by

turning a peg, a quarter turn being sufficient for the

purpose, and thus, in the key of G major, it is only

necessary to raise the

pegs of the F string. In 1903 there was published an excellent

Tutor for the Irish Harp, by Sister M. Attracta Coffey,

followed by two books of Irish melodies.

CHAPTER XX.

THE DOUBLE-ACTION HARP

Marie Antoinette harp.

Sebastian Erard. Improved single-action harp of 1792. Double-action

harp of 1810. Advantages of the double-action harp. Appreciation

by John Thomas. The ''Grecian" harp of 1815. The Gothic harp.

It has been seen that the

Cousineaus, père et fils, had improved on Hochbrucker's

invention in regard to the pedal, by the use of small metal

plates (béquilles), enclosing the strings, and by the

introduction of a slide for raising or lowering the bridge-pin,

thus regulating the length of the string. But, above all, they

doubled the pedals and the mechanism connected therewith, and

just fell short of the honour of inventing the double-action

harp—the work of that famous mechanician Sebastian Erard, a

name identified not only with the harp, but with the pianoforte.

Naderman's improvements

have also been alluded to. The lovely harp which he made for

Marie Antoinette in 1780 is now in the South Kensington Museum.

To Sebastian Erard is undoubtedly

due the deserved position which the harp

holds today, whether in the orchestra or as a solo

instrument. It was in 1786 that this remarkable

man (born at Strasburg, on April 5th,

1752) commenced a series of patient investigations

which resulted in the magnificent double-action

harp of today. >

In 1792 Erard took out

a patent in London for an improved pedal-action harp,

and returned to Paris in 1796, having started a

successful piano and harp factory in the English metropolis. This

improved harp was still only single-action, but

with the immense advantage of the fork mechanism—that

is to say, the disc containing the two studs, which, in

its revolution by the action of the pedal, gripped the

string without drawing it from the level of

the other strings, as was previously the case. Some

of these improved single-action harps, by Erard, are till to be seen, and their

general style of decoration was marked by

a ram's head carved at the top of the

pillar.

Between the

years 1801 and 1805 Erard worked at models of a harp with a

double movement, and in 1809 he patented his first idea of the

double-action harp. His first effort in that direction

was only partially double,

as the double-movement only extended

to the notes A and D. At length, in 1810,

Erard's genius triumphed over all obstacles, and he was able

to employ the double-action fully—the instrument being generally

known as the "Grecian" harp. He took out a patent for the double-action

harp in the same year.

Erard employed seven pedals

only, as in the single-action harp; but developed the cranks

and levers acted on by the pillar-rods so as to operate on the

discs. Instead of the cumbrous and numerous plates employed

by Cousineau, Erard only used two brass ones, forming the comb,

and he got rid of the antiquated plan of building up the sound-board

with staves.

As Erard's

double-action harp is tuned in C flat, by using the seven pedals

successively the performer can readily play in the keys of Gb,

Db, Ab, Eb, Bb,Fb, and Cb. A further action of the pedal

raises the pitch another semitone, thus effecting a change of

a whole tone, and makes the instrument capable of being played

on in the keys of G, D, A, E, B, F, and C. As a result,

Erard succeeded in doing away with all complications of

fingering for the various

scales and keys—a difficulty not unknown to learners

on the piano,—as by his remarkable invention, the

fingering on the double-action harp is the same in all

keys.

John Thomas thus writes

of Erard's invention: "The pedal-harp is an immense

improvement, in a musical sense, upon any former invention,

as it admits of the most rapid

modulation into every key, and enables

the performer to execute passages and combinations that

would not have been dreamed

of previously. In the double-action harp,

as perfected by Erard, each note has its flat, natural,

and sharp, which is not the case with any other stringed instrument; and

this enables the modern harpist

to produce those beautiful enharmonic effects which

are peculiar to the instrument. Another remarkable advantage

is the reduction in the number of strings to

one row, which enables the performer not only to keep

the instrument in better tune, but to use a thicker String,

and thus attain a quality of tone, which, for mellowness and richness may

be advantageously compared

with that of any other instrument."

Sebastian Erard, who took

out a patent for his perfected repetition grand piano action,

in London, in 1821, died at Paris, August 5th, 1831, and was

succeeded by his nephew, Pierre

Erard. From 1810 to 1835 the "Grecian" model held the field;

but, in 1836, Pierre Erard patented the "Gothic" harp, which

soon superseded the "Grecian."

The Gothic Harp was not

only a larger instrument, but one of a much more powerful tone.

The action was practically

unchanged, but Pierre Erard effected several improvements, notably

such as were afforded by a greater space

between the strings and a broader sounding board. He died at

the Chiteau de la Muette, Passy, near Paris, on August 18th,

1855.

The illustrations on the

preceding page represent the latest forms of Gothic Harp made

by the famous house of Erard.

CHAPTER XXI

VIRTUOSI OF THE NINETEENTH

CENTURY.

Madame Spohr. Dizi.

Henry Horn. C. A. Baur. Neville Butler Challoner. Thomas Paul

Chipp. Bochsa. Parish Alvars. J. B. Chatterton—Eulenstein. A.

Prumier. Charles Oberthür. John Thomas. Aptommas. John Cheshire.

Among the virtuosi on the

harp whose playing attracted considerable attention during the

early years of the nineteenth century, Madame Spohr was conspicuous. She accompanied

her husband in his tours, and performed

many pieces for violin and harp, as well

as some charming solos specially composed for her by Spohr.

She appeared as a harpist for the last time in London at Spohr's

farewell concert, in 1820, and her playing elicited the warmest

plaudits. Two years later she retired, owing to ill-health,

and died in 1834.

Dizi was for many years

resident in London, and displayed much ability in his fourfold

capacity as harpist, teacher, composer,

and inventor. In the season of 1820 he was the leader of the

band of harps—twelve in number—employed

by Sir Henry Bishop at Covent Garden oratorios. Among his harp

compositions were sonatas, fantasias, and romances.

As an inventor Dizi must

be credited with a praiseworthy effort to improve the volume

of tone of the harp. His "perpendicular harp" was built on the

principle that the tension of the strings acting on a centre

parallel to the centre of the column as well as to that of the

sonorous body required strong metal plates; and the column supporting

the mechanism took the pressure on the centre. The name "perpendicular"

was given by Dizi to his improved harp, as the strings were

placed vertically, making no angle. He also substituted a damper

pedal (invented by William Southwell, of Dublin, in 1804) for

the swell, by means of which the sous étouffées were

produced, thus differing from the prevailing method—by the hand.

Henry Horn (born in 1789)

was a Parisian, who studied under Meyer and Elouis; and, in

1812, he settled in London, having the year previously introduced

Erard's double-action harp at Bath. Both as a teacher and a

player he was extensively patronised, and he published numerous

pieces for his instrument, including an Instruction Book

for the Single and Double-Movement Harp. After the year

1817 his fame as a performer was eclipsed by that of Bochsa.

Another distinguished harpist

who settled in London was Charles Alexis Baur. Born at

Tours, in 1789, he inherited his musical talent

from both his Charles father and mother, who were teachers of

the Baur piano and harp. In 1805 he proceeded to Paris, where he perfected

his knowledge of the harp under Naderman. Between the years

1820 and 1825 he had a large clientele in London, and composed

a variety of pieces for the harp, as well as some arrangements

for the harp and flute.

Neville Butler

Challoner, born in London, in 1784, was a violinist in his early

days; but, in 1803, took up the study of the harp

and became a brilliant player. He was appointed

harpist at the Opera House in 1809, and continued

in that position till 1829. He

published a large quantity of music, including A Method

of the Harp (1806), duos concertantes, romances, polaccas,

fantasias, etc.

Thomas Paul

Chipp deserves notice as a remarkable English harpist. He

first saw the light in London in 1793, and studied the harp

when quite a child. In 1720 he was appointed

harpist to Covent Garden Theatre,

and published some pieces for his instrument. He

is better remembered as the player of the "Tower

drums," and as father of the late Dr. E. T. Chipp. His

death occurred on June 19th, 1870, four years

after his retirement.

Incomparably greater than

any of these was Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa,

the son of a flute and clarinet player, born at Montmedy

in the department of the Meuse, on August

9th, 1789. Under his father's tuition he

became very proficient, and at eleven years of

age played a flute concerto of his own composition. In 1805

he composed an oratorio, followed by an opera, and in 1806 took

seriously to the study of the harp. Having studied under Catel,

Mehul, Naderman, and Marin, he laboured continually to produce

new effects from his instrument, and in a short time raised

the harp to a position in the orchestra hitherto undreamed of.

Bochsa was appointed harpist

to the Emperor Napoleon in 1813, and, on the restoration of

Louis XVIII, in 1815, was commanded to compose an opera (Les

Héritiers Mechaux), followed by his appointment as royal

harpist in 1816. Unfortunately, owing to certain tampering with

figures, he was obliged to seek a friendly haven in England

in 1817, and, in his absence, was formally tried and condemned

to undergo a heavy sentence, in addition to a fine of four thousand

francs.

It is a commonplace of

musical history that Bochsa succeeded in giving a tremendous

vogue to the study of the harp in London, reckoning

amongst his pupils many subsequently famous harpists, like Parish

Alvars and Chatterton. As an illustration of the harp craze

at this epoch, it may be mentioned that at the Covent Garden

"oratorios" of 1821, whilst Sir Henry Bishop employed twelve

harps, headed by Dizi, Sir George Smart, at Drury Lane, had

thirteen harps, with Bochsa as leader.

In 1823 Bochsa was Professor

of the Harp at the Royal Academy of Music, and leader of the

Lenten oratorios; and in 1826 he replaced Costa as conductor

at the King's Theatre— a position which he held till 1832. From

1817 to 1837 he gave annual concerts, the programmes of which

invariably contained novelties by himself.

Sad to relate, his irregularities

were so notorious that he was dismissed from the Royal Academy

of Music in 1827, and at the close of the year 1839 he eloped with the

wife of Sir Henry Tour Bishop. For sixteen years he had

successful concert tours in every

quarter of the globe, save France. His reception in America

was very cordial, whilst in Ireland he created a perfect furore.

During dis visit to Dublin, in 1837, Bochsa carefully examined

the "O'Brien" harp, and expressed his wonder at such a venerable instrument.

At length, in Australia, he was stricken with a fatal attack

of dropsy, to which he succumbed, at Sydney, on January 6th,

1856.

Though regarded

as a charlatan by many writers, there is no gainsaying the fact

that Bochsa stands forth as one of the greatest virtuosi of

the nineteenth century. Had he been less prolific as a composer,

he would also rank among the foremost writers for the harp.

Several hundred compositions of all kinds appeared from his

fertile pen, but not half-a-dozen were of a perennial value.

His last composition was a Requiem, which was performed at his

own obsequies. His Harp Method is still used.

Elias Parish Alvars was

born of Jewish ancestry, at Teignmouth, on February 28th, 1808. Having

studied the harp under Dizi, Labarre, and Bochsa, his fame as

a harpist began to be recognised in 1824. Between the years

1831 and 1836 Alvars he was almost continuously on the Continent,

giving harp performances in Germany, Italy, and Austria, with

the utmost success. During the season 1836-37 he was back again

in London; but from 1838 to 1841 he journeyed in the East, availing

of the tour to collect Oriental tunes, especially those of Turkey

and Asia Minor.

Parish Alvars

was at Leipzig in 1842, and at Berlin, Frankfort, Dresden, and

Prague in the following year; subsequently appearing

at Naples, where was much admired. During the year 1846 he foregathered

with Mendelssohn at Leipzigand finally settled down at Vienna

in 1847, having been appointed chamber harpist to the Emperor.

His death occurred at Vienna, January 25th, 1849, aged 41.

His playing was that of a true artist, and he continually

aimed at securing fresh effects. His compositions number about

a hundred,including four concertos for harp and orchestra, also

fantasias, transcriptions, romances, and melodies for harp and

piano, many of which are still in request. His collection of

Eastern melodies was published as Voyage d'un Harpiste en Orient.

John Balsir Chatterton,

born at Portsmouth, in 1802, evinced a taste for the

harp at an early age, and was placed for instruction

under Bochsa and Labarre. His first

public appearance was at a concert given by the

boy-pianist, George Aspull, in London, in 1824. Three

years later he was appointed Professor of

the Harp at the Royal Academy of Music, in succession

to Bochsa, and in 1842 was honoured by the appointment as harpist

to Queen Victoria.

Not alone was Chatterton

a distinguished performer on the harp, but he was a composer

of numerous transcriptions from the operas, and of songs with

harp accompaniment. For the long period of almost forty-four

years he taught at the Royal Academy of Music, and formed the

style of hundreds of harpists. He died in London, April 9th,

1871.

Although the Jews' harp

cannot rightly be regarded as a serious instrument,

yet, in the season of 1877-78, London went wildly enthusiastic

over the performance of Charles

Eulenstein, a native of Wurtemberg, on sixteen

Jews harps. For years this extraordinary

genius had applied himself to the best method of producing novel

effects from this primitive instrument, and he succeeded admirably.

In later years he became a teacher of the guitar at Bath, and

in 1870 returned to Germany, ending his days in Styria, in 1890,

aged 88.

Antoine Prumier, an eminent

Parisian harpist, was born July 28th, 1794, and, after a

preliminary course of lessons from his mother, entered the Conservatoire

in 1810, obtaining the second harmony prize in 1812. In

1818 he became harpist in the orchestra

of the Italiens, and in 1835 took up a similar position at the

Opera Comique.

In November 1835, on the

death of Naderman, Prumier was appointed Professor of the Harp

at the Conservatoire, which post he held till 1867, when he

resigned in favour of Theodore Labarre. Meantime, on his retirement,

in 1840, from the Opera Comique, he was succeeded by his son

Conrad, an eminent harpist, born in 1820.

Prumier's greatest triumph

was in 1865, when he received the Legion of Honour. Of his numerous

concertos, fantasies, rondos, and airs varies, few have survived,

though many of them were very popular forty years ago. He died

suddenly on January 21st, 1868, leaving a son, Conrad, who inherited

to the full the ability of a true harp lover. Conrad Prumier

was so remarkable as a harpist that, on the death of Labarre

(April 1870), he was appointed professor of the instrument

at the Conservatoire. He died at Paris, in 1884.

As an ardent exponent of

the Welsh triple harp Ellis Roberts was famous even outside

the Principality. Born at Dolgelly in 1819, he was appointed

harpist to the Prince of Wales in 1866, and died in London,

December 6th, 1873. He will be best remembered

as author of the only Tutor published for the Welsh

harp.

Charles Oberthiür shone

both as a virtuoso on the harp and as a composer. Born at Munich,

on March 4th, 1819, he studied under Elise Brauchle and G. V.

Roder, and in 1837 was engaged as harpist to the Zurich theatre.

In 1840 we find him at Wiesbaden, and in 1842 he took a position

at Mannheim. At length, attracted by the promises of influential

English friends, he determined to visit London, the Mecca of

most virtuosi.

Oberthür settled in London

in October 1844, and at once found favour both

as a teacher and performer, but excelled

as a popular composer. For a time

he was harpist at the Italian Opera, but his

other engagements prevented him from continuing in

the position.

In addition

to his numerous solos, duos, trios, and concertinos

for the harp, Oberthür composed an opera, Floris

de Namur (produced at Wiesbaden), and a fine Mass

in honour of St. Philip Neri, as also Overtures to Macbeth and Rübesahl. He

died at London in 1895.

John Thomas,

better known in the Principality as "Pencerdd Gwalia", has had

a world-wide fame both as a harpist and composer. He first

saw the light at Bridgend (Glamorganshire), on St.

David's Day (March 1st), 1826, and

at the age of eleven performed at the Eisteddfod

held at Abergavenny, winning a silver harp .Entering

the Royal Academy of Music in 1840,

he had the advantage of J. B.

Chatterton's tuition on the harp; whilst he studied

compositions under Charles Lucas and

Cipriani Potter, and the piano under C. J. Read. For

eight years he availed fully the teaching given at the

Academy, and composed an opera entitled Alfred the

Great, a symphony, some overtures,

a harp concerto, quartets, etc.

In 1850 he was appointed

harpist in the orchestra of Her Majesty's Opera, and in 1851

he had a successful concert tour on the Continent, playing at

the Leipzig Gewandhaus Concerts on October 3rd, 1852. From 1851

to 1861 he journeyed every winter to the big musical centres

of Europe, and played to delighted audiences in France, Germany,

Russia, Austria, and Italy, appearing for the second time at

Leipzig in January 1861.

At the Aberdare Eisteddfod

of 1861, Mr. Thomas was conferred the title of "Pencerdd Gwalia,"

or "chief of the Welsh minstrels"; and on July 4th, 1862, he

gave his first concert of Welsh music at St. James's Hall, London,

employing a chorus of four hundred, and a band of twenty harps. This

performance gave a tremendous fillip to harp-playing, and adequately

proved the capabilities of the Erard double-action harp as an

orchestral instrument. For thirty years Thomas gave an annual

harp concert in London, which afforded an opportunity of bringing

forward some of his own compositions.

At the Swansea Eisteddfod

of 1863 his dramatic cantata Llewelyn was performed;

and he conducted his most ambitious work, The

Bride of Neath Valley, at the Chester Eisteddfod

of 1866, on which occasion

he was given a presentation of five hundred guineas, in acknowledgment

of his invaluable services in the cause of Welsh music. A fine

harp concerto of his was performed at the Philharmonic (London)

in 1852. However, he is better known by his harp transcriptions

of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Handel, and Schubert.

On the death of Chatterton,

in 1871, Thomas was appointed Professor of the Harp at the Royal

Academy of Music, and harpist to Queen Victoria. In the same year he was

conductor of the Scholarship Welsh Choral Union, a body which

popularised Welsh music by its concerts, carried on for six

years. So great was his enthusiasm in the development of music

in Wales, that he collected a sum sufficient to endow a scholarship for

natives of the Principality at the Royal Academy of Music in

1883, which scholarship bears his name.

American readers need scarcely

be reminded that Thomas acted as adjudicator at the Eisteddfod

at Chicago Exposition, in 1893. On September 6th of that year

his Llewelyn was produced with marked success, and on September

18th his harp concert was even a greater triumph.

At the Cardiff (Wales)

Conference of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, in January,

1897, Thomas read a researchful paper on the "Music of Wales,"

on which subject he was a prime authority. Of more permanent

value is his collection of Welsh melodies for voice, with harp

accompaniment, in four volumes.

Thomas Thomas,

a younger brother of the preceding harpist (better known as

Aptommas), is an excellent performer and teacher, though his

fame has been overshadowed by that of Jonn

Thomas. Born at Bridgend, in 1829, he studied

the harp from his early years, and gave many successful

concerts both at home and on the Continent, between

the years 1851-67. His History of the Harp,

issued in 1859, contains much useful information, though

not altogether trustworthy.

Aptommas, on January 18th,

1872, performed at the Gewandhaus Concerts, Leipzig,

and his playing was much admired. His

success in America is too well known to be dwelt

on, and as recently as January 16th,

1905, he gave a very fine concert at the

Carnegie Hall, New York. As a teacher he is deservedly

in high repute, and one of his best-known pupils is

Owen Lloyd, the great Irish harpist. <

Among the virtuosi of the

last century John Cheshire claims a high place, and he also

has distinguished himself as a composer. He was born at Birmingham

on March 28th, 1839, and took to the harp when quite a child.

His harp studies were made under the direction of Chatterton

at the Royal Academy of Music from 1852 to 1855, and he completed

his musical training under Macfarren. In 1855 he was appointed

harpist in the orchestra of the Royal Italian Opera, and, ten

years later, was given the post of principal harpist at Her

Majesty's Theatre. His cantata, The King and the Maiden,

was produced at St. James's Hall, London, on April 20th, 1865.

>

Cheshire's concert tours,

between the years 1858 and 1879, embraced South America (where

he produced his opera Diana), Norway, Sweden, and other

centres, and his harp playing was everywhere much admired. In

1880 he led a band of harps at the Belfast Musical Festival, organised by

the late Walter Newport. In 1886, his cantata, The Buccaneers,

was published, and he also issued numerous pieces for the harp,

including six romances.

Like other harpists, Cheshire

was tempted to cater for the growing taste in favour of the

harp in America, and accordingly, in 1887, he settled in that

country, becommg harpist to the National Opera Company in 1888.

He secured a good teaching connection

in Brooklyn, in 1890, where he resided for some years. Mr. Cheshire,

it should be added, was harpist to H.R.H. the late Duke of Edinburgh.

CHAPTER XXII

THE HARP IN THE ORCHESTRA.

Louis Spohr. Giacomo

Meyerbeer. Hector Berlioz. The ideal orchestra. l'Enfance

du Christ. Franz Liszt. Michael William Balfe. Richard Wagner.

The Rheingold. Die Walkure. Charles Gounod. Franz Lachner.

Charles Oberthür. A strange combination. Dom Perosi. The future

of the harp.

Louis Spohr (1784-1859),

as before stated, scored very successfully for the harp,

doubtless due to the fact that his accomplished wife—Dorette

Scheidler—was an excellent harpist. In

Messrs. Breitkopf and Hartel's catalogue of

Spohr's works there are enumerated

seven compositions for the harp—namely, Nos. 16, 35,

36, 113, 114, 115, and 118, of which his Sonate Concertante

for Harp and Violin, and his Fantasia for Harp

and Violin are well known.

Meyerbeer

(1791-1864), a very Titan in his way, made a distinct

advance on Spohr as far as the orchestral use of the harp

is concerned; in fact, he may be said to be the first great

modern composer who utilised the double-action

harp in orchestra proper, and,

in this respect, was the forerunner of Wagner. He employs

two harps most effectively in Robert le Diable.

< Berlioz (1803-69), the

colossus of the orchestra, fully appreciated the advantage

of the harp in orchestral work, as may be evidenced from his

sketch of the ideal orchestra: 142 strings, four of which

are tuned an octave below the double basses; 30 grand pianofortes)

30 harps, etc.

Even abstracting from the

eccentric ideals marvellously gifted king

of the orchestra, there is no doubt but that his employment

of the harp in the orchestra, whether for opera, oratorio,

cantata, or symphony, has rendered the instrument absolutely

indispensable in the expression of certain effects. No other

instrument—or combination of instruments—in the orchestra

can give the desired tone-colour to certain passages, such

as those illustrative of angelic choirs, etc. In his autobiography

he says: "Shut me up in a room with one or two Erard harps,

and I am perfectly happy."

It is not

generally known that it was to the inspiration of his Irish

wife—Henrietta Smithson, of Ennis, Co. Clare—that

Berlioz composed his Maude, an arrangement

of nine Irish melodies as set by Tom Moore.

One of the most charming pieces

in his exquisite L'Enfance du Christ (originally

written under the title of Fuite en Egypte)—his one oratorio,

composed between the years 1850-54—is a trio for two flutes

and a harp.

Liszt (1811-86), even more

than Berlioz, utilised the harp for his orchestral settings. His

beautiful "Hymn de l'Enfant a son Reveil" is arranged for

female chorus, organ, and harp; whilst his "St. Cecilia" is scored

for mezzo-soprano, chorus, piano, harp, and harmonium. It

is interesting to add that, as a result of the scoring of

Meyerbeer, Berlioz, and Liszt, the orchestra of the Grand

Opera of Paris, in 1854, had twenty 1st violins, twenty 2nd

violins, four harps, etc. The Bayreuth orchestra of 1876

had six harps—a final triumph for the double-action harp.

It was only natural that

Balfe (1808-70) should utilise Erin's national instrument,

and, therefore, we are not surprised to find him employing

the harp in his operas. He uses a remarkable combination—viz.,

the cornet, harp, and corni, to accompany "The Light of Other

Days" in his Maid of Artois.

Wagner (1813-83),

in the highest degree, has definitely fixed the place of

the harp in the modern orchestra, although

Berlioz had, in a sense, forestalled him; indeed, Wagner himself

admits that as early as 1840 he profited

greatly by a study of Berlioz's instrumentation. What can

be more beautiful than the exquisite music assigned

the harp in The Rheingold? When, at the

finale, the valley of the Rhine is glorified

with a rainbow, and the

gods pass across the chasm to the German

Valhalla, Wagner uses six harps, scoring independent parts

for each, as a glorious accompaniment for the scene. A duo

or trio of harps would be thin by contrast with the full orchestral

colouring in this glittering pageant, but the Bayreuth master

employs six harps, which, being scored for separately, produce

an ethereal effect. And be it remembered that this use of

the harp in the orchestra was portion of the well-considered

plan of guiding themes, and appropriate tone-colouring for

his wonderful dramas, for Wagner did nothing at haphazard.

Again, in

the third act of Die Walkure, the score of which

is a perfect maze of guiding themes in a gorgeously coloured

web of delightful orchestration, harps are employed in the

first scene with peculiarly fine effect.

Another great master, Charles

Gounod (1818-93), scored judiciously for

the harp in his operas, masses, and motets; in fact, he

has been accused of writing too sensuously,

and, on thataccount, some of his sacred

pieces have been vigorously denounced

by the purists in art.

Franz Lachner (1804-90),

conductor of the Opera at Mannheim, and Hofkapellmeister at

Munich, wrote several pieces for

the harp, including two Concertos for harp

and bassoon, and some Trios.

Charles Oberthür,

whose powers as a virtuoso have been previously alluded

to, composed Lorely, a legend for harp and orchestra;

as also some Trios for harp, violin,

and violoncello, and a Quartet for four harps.

In his excellent work on

Chamber Music, Mr. N. Kilburn mentions a very unusual

combination—namely, an Octett (op. 32)

by a Russian composer, Liadoffin (1855), scored for piccolo,

two flutes, three clarinets, harp, and bells.

Passing over a number of

other composers who have made use of the harp in the orchestra,

the present Maestro at the Vatican, Dom Perosi, has most effectively

employed harps in his latest cantata, produced in Rome

in December 1904, in honour of the Jubilee of

the Immaculate Conception. Perosi has increased his reputation

by this cantata, and the critics are unanimous in praising

the skilful manner in which he has introduced a band of harps

in the orchestral scoring.

Thus, the future of the

harp, as an instrument of the orchestra, is tolerably secure,

although it is a matter of regret that, as a domestic instrument,

it has been displaced by the pianoforte and violin. On national

and sentimental grounds the harp will always be associated

with Celtic gatherings, whether Irish, Scotch, Welsh, Breton,

Cornish, or Manx. Of a certainty, the Irish harp will not

be allowed to die, especially as Irish harps are comparatively

inexpensive, and not over difficult to play. Moreover, just

as the harpsichord can only give the true old-world flavour

to pieces written for that instrument, so also the harp-melodies

of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are best performed

on the Irish harp.

But, in general, the vogue

of the double-action harp, as a solo instrument, and as an

appanage of the average drawing-room, has almost disappeared,

the chief reason being its prohibitive price (£120 to £200),

and the difficulty of becoming a good performer. And

it must be added that the advent of

the cycle and the motor has had not a little influence

in contributing to the comparative neglect of the queen instrument

of the salon.

However, as we have seen,

the harp is now an indispensable instrument of all large orchestras,

and its resources have been amply utilised by all the great

masters of music for the past fifty years. Perhaps some future

composer will make its position even more prominent, and thus

bring about a more general study of this most graceful of

instruments.

In the hands of a Thomas,

a Zamara, a Barber, a Schuecker, a Cheshire, or of any great

virtuoso, what wonderful effects are produced! And when the

celestial strains of the harp are heard in grand opera, as

in the Rheingold, or Die Walküre, then,

indeed, comes back the old glamour of the instrument whose

history is as old as the earth itself, the story of which

we have endeavoured, however inadequately, to tell in the

preceding pages.

EPILOGUE.

There are many phases of

the harp that the keen critic may perhaps feel surprised at

no reference to—e.g. harp mechanism, harp ornamentation,

harp legends, etc.; but these did not exactly come within

the scope of the present volume. Nor did we enter into the

construction of the instrument from a technical point of view,

the aim of the series being to present in a popular way a

connected story of the particular phase of musical art dealt

with. We have also omitted any notices of twentieth-century

composers or virtuosi, for the sufficient reason that an unbiassed

judgment can scarcely be found of the musical happenings of

the past five years. However, we have endeavoured to put before

the reader, in simple language, the essential features of

the history of the harp from prehistoric times to the close

of the last century.

Going back into the misty

past, the harp has been associated with the most ancient peoples.

Pretermitting the numerous allusions in the Bible, the discoveries

of the past ten years have amply confirmed previous views as to early

existence of harps among the Cretans, Babylonians, Egyptians,

and other nations. Petrie, Evans, and Boscawen have unearthed

vases, tablets, and seals with pictorial representations of

harps, of a date at least three thousand years before Christ.

Beautiful Apollo lyres, too, have recently been discovered

in Greece, and the visitor of today may feast his eyes on

the beautiful instruments depicted on marble in the National

Museum at Athens. Mr. Boscawen is inclined to believe that

one of the Chaldaean sculptures, dating from over four thousand

years before Christ, depicts the harp and pipes as attributed

to Jubal.

It is truly marvellous

that the harp, which seemed threatened with extinction at

the close of the seventeenth century, should have received

a new lease of life early in the succeeding century. Not alone

was there a revival of the instrument, but, as we have seen,

the harp began to take its place in the orchestra ere the

close of the eighteenth century. The improvements of Hochbrucker,

Cousineau, and Erard have elevated the minstrel's harp almost

to the plane of the violin, and most of the great masters

of the nineteenth century have recognised the value of the

double-action harp.

In ancient Ireland there

are numerous legends in which the harp plays no unimportant

part. Similarly, in England, Scotland, and

Wales, there are innumerable legends of harps and harpers;

but these belong to the regions of romance, and cannot hope

for a place in a sober historical narrative.

Notwithstanding the very

advanced state of modern orchestration and its influence on

the accompaniment of even simple ballads, it is a hopeful

sign of the times to observe the rising enthusiasm in favour

of old folk tunes and songs. Within the past eight years the

once despised folk melodies of the olden time are become things

to be desired, and whether in Germany, America, England, or

Ireland, there is an undoubted tendency to ferret out and

cultivate old folk tunes.

And just as a love for

the melodies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has

grown up, having been introduced into all our primary and

secondary schools, so also a revival of the harp has taken

place. In Ireland, the Feis Ceoil and Oireachtas; in Wales,

the Eisteddfod; and in Scotland, the Mod—all contribute their

quota towards the popularising of the harp. Thus, the harp

lives on, ever and anon reminding the listener of days that

are gone, conjuring up memories of old-time artists, whether

in Babylonia, Persia, Greece, Ireland, Judaea, Britain, Egypt,

and Chaldea; acquiring a new lease of life in the hands of

Bochsa, Oberthiir, and Thornas; and finally taking its place in the orchestral

scores of Wagner, Berlioz, Liszt, Gounod, Perosi. Who knows

but that in some mysterious and as yet inscrutable way the

harp may again become the instrument of fashion? One thing

is certain, that the harp has a charm all its own, whilst

it can point to traditions of the remotest antiquity.

|

|

|

|