|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

|

CHAPTER VI.

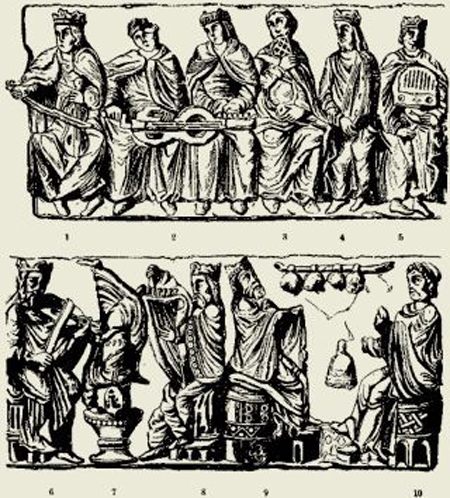

MEDIEVAL HARPS AND HARPERSIn the Church of St. George, Boscherville, in Normandy, there is a fine

bas-relief exhibiting an eleventh-century concert. It forms the

capital of a pillar in this old abbey-church, and the reader can

best judge of the mediaeval instruments from the subjoined illustration.

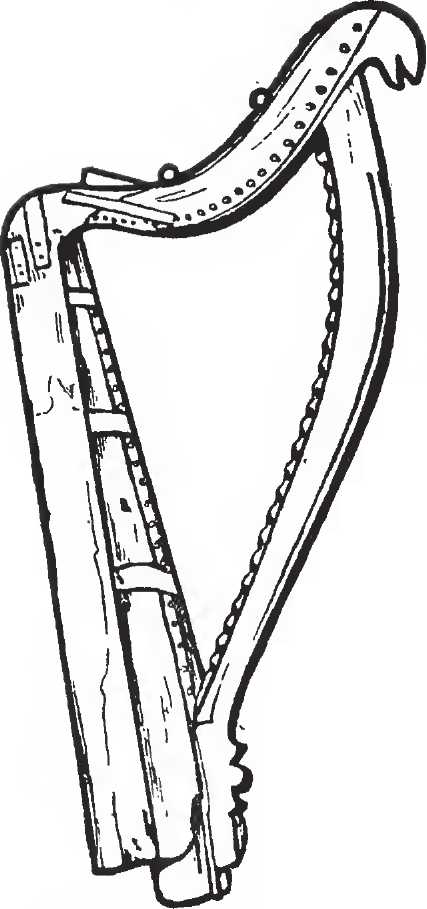

Sir Samuel Ferguson refers to the appearance of a harp on the cover of

an Irish manuscript in the Stowe Library, which harp is a cruit,

having a fore-pillar and Sounding board. There is also a drawing

of a harp of twenty-nine strings on a relic-case containing the

Fiacail Phadraig (tooth of St. Patrick), dated 1350, formerly belonging

to Sir Valentine Blake of Galway.

Under date of A.D. 1100, the Annals of Ulster (Rolls Series) chronicle

the death of Ferdomnach the Blind, Lector of Kildare, who is described

as a Cruiterechta, or “Master of Harping”. Some years later—namely,

in 1119—there is a record of the death of Dermod O'Boylan, “Chief

Music Master of Ireland”. John of Salisbury, about the year 1168, declares that in the Crusade of

Godfrey of Bouillon, in 1099, there would have been no music at

all had it not been for the Irish harp, or, as Fuller says, “the

consort of Christendom could have made no music if the Irish harp

had been wanting”. Brompton, writing in the reign of Henry II, praises the skill of Irish

musicians, especially the performers on the cruit, timpan, and bag-brompton

pipe. Above all, he was astonished at the superior playing

of the Irish harpers, their “animated execution, sweet and pleasing

harmony, quivering notes, and intricate modulations”, etc. But even Brompton is eclipsed in eulogy by that strenuous Welsh ecclesiastic

known as Giraldus Cambrensis, or Gerald Barry, Archdeacon and Giraldus

Bishop-elect of St. David’s, who came over Cambrensis to Ireland

in 1183. He thus writes of the on the School of Irish Harpers:—

“They are incomparably more skilful than Irish any other nation I have

ever seen. For Harpers their manner of playing on these instruments

[cruit, clarsech, and timpan], unlike that of the Britons, to which

I am accustomed, is not slow and harsh, but lively and rapid, while

the melody is both sweet and pleasing. It is astonishing that in

such a complex and rapid movement of the fingers the musical proportions

[as to rhythm] can be preserved, and that throughout the difficult

modulations on their various instruments the harmony—notwithstanding

shakes and slurs, and variously intertwined organising—is completely

observed”. The Latinity of Giraldus is not easy to give in an English dress, but he

evidently wishes to display his knowledge of musical technicalities

as then in vogue. He describes “the striking together of the chords

of the diatesseron [the fourth degree of the scale] and diapente

[the fifth] introducing B flat”, and “the tinkling of the small

strings coalescing charmingly with the deep notes of the bass”.

He concludes as follows:—"They delight

with so much delicacy, and soothe so softly, that the excellence

of their art seems to lie in concealing it2." In 1225, the Annals of Loch Cé, in an obituary of Aedh O'Sochlann, Vicar

of Cong, described him “a master of vocal music and harp-making,

and the inventor of a new method of tuning”. This entry is

important as showing that this clerical harper had devised a new

harp as well as a new plan of tuning the national instrument. The

pity of it is that no particulars are given

as to the new method of tuning.

During the twelfth century, in England, there are some references to harps

and harpers. Passing over Blondel, the minstrel of Richard I, we

find in Madox’s History of

the Exchequer that, in 1183, Geoffrey the Harper had a pension

from the Benedictine monks of Hyde, near Winchester. Again, Abbot

Samson, of Bury St. Edmunds, entertained harpers and minstrels;

and, in 1242, there is a record of a payment ordered to Richard

the Harper, and a pipe of wine to Beatrice, the wife of the said

Richard. Burney says that “all the most ancient poems, whatever was their length,

were sung to the harp on Sundays and on public festivals”. He adds

that Robert de Brun (1303) sings thus of Grosteste, Bishop of Lincoln

(1235-1253):— “He loved much to hear the harp, For man's wit it maketh sharp; Next his chamber, beside his study His harper's chamber was fast the by. Many times by nights and days He had solace of notes and lays”. Prince Edward (afterwards King Edward I) took his harper Robert with him

to the Holy Land, in 1270, who, when his royal master was wounded

at Ptolemais, “rushed into the apartment during the struggle and

killed the assassin”. Certain it is that in the State Papers of

the fifth of Edward I (1276), a payment is entered on the Exchequer

Rolls for Robert, the King’s harper. There is an illustration of a king playing on a small portable harp in

Strutt’s Dresses of the English

People. This figure of the thirteenth century is represented

as having the harp resting on his knees, and the number of strings

may be taken as fourteen. From the illustration it is evident that

this instrument is a replica of the cruit, a small Irish harp, and

it is beautifully ornamented. Not so long ago it was generally believed that the inclusion of the harp

in the arms and coinage of Ireland dated only from the

reign of Henry VIII, but the fact is that the national instrument

appears on coins issued by King John and Edward I; and, in 1251,

we read that “the new coinage was stamped in Dublin with the impression

of the King’s head in a triangular harp”. A harp was originally

the peculiar device of the arms of the Leinster province, and it

was subsequently applied to the whole kingdom of Ireland—namely,

in heraldic language, “on a field vert, a harp or, stringed argent”.

Ralph Higden, a distinguished historiographer at the beginning of the fourteenth

century, describes the music of the Irish harp as “musica peritissima”;

and John de Fordun, a Scottish priest, who wrote in the same century,

says that Ireland “was the fountain of music in his time, whence

it then began to flow into Scotland and Wales”. The European fame of the Irish harp was well maintained at the close of

the thirteenth century, as is attested by the following quotation

from Vincenzo Galilei, who gives Dante (1265-1321) as his authority:—

“This most ancient instrument was brought to us from Ireland (as Dante

says), where they are excellently made, and in great

numbers, the inhabitants of that island having practised

on it for many and many a century. Nay, they place it in the

arms of the kingdom, and paint it on their public buildings, and

stamp it on their coinage, giving as a reason their being descended

from the royal prophet David. The harps which these people

use are considerably larger than ours, and have generally the strings

of brass, and a few of steel for the highest notes, as in the clavichord.

The musicians who perform on it keep the nails of their fingers

long, forming them with care in the shape of the quills which strike

the strings of the spinet”. Some Irish minstrels and harpers accompanied King Edward I in his expedition

to Scotland, in 1301, and again in 1303. Let us now turn to England. The future King Edward II wrote, as Prince

of Wales, to the Abbot of Shrewsbury, “asking that a famous fiddler

in the Abbot's household should teach the prince’s rhymer the minstrelsy

of the crowdy, and that the rhymer might be housed at the convent

whilst he was learning”. In 1309, harpers attended the installation ceremony of Ralph, Abbot of

St. Augustine’s, Canterbury, and in 1310, Robert, harper to King

Edward II, was present with other minstrels at York, when a sum

of forty marks was distributed among the musicians. On April 14th,

1311, Edward II granted a safe conduct under privy seal in favour

of Raymond Cousin, “the King's minstrel”, who was going on a pilgrimage

to Santiago. In 1329, there is allusion to Thomas Morsel, the

harper, whilst another entry has reference to Alexander Williamson,

the bishop’s harper. At the battle of Bragganstown, near Ardee (Co. Louth), on June 10th, 1329,

was slain Maelrooney O'Carroll, Chief Harper of Ireland. The Irish

Annals describe him as pre-eminent in his art, and he is said

to have played on a double harp. One contemporary chronicler

styles him a timpanist as well as harper, and “the inventor of chord

music”, whilst the annalist of Clonmacnoise adds that “no man in

any age ever heard or shall hereafter hear a better harper”. Among the Records of the Guildhall of London there is a document to the

effect that, about the year 1334, minstrels were wont to be employed

by the London Corporation at their entertainments. It is well, however,

to point out that jongleurs,

or minstrels, must not be confounded with harpers. The latter body

looked down on the minstrels, who, as a rule, were Bohemians of

a not too savoury character. At the same time

it must be borne in mind that the French minstrels, in 1331, built

the Church of St. Julien des Menestriers. The Germans, too,

had their minstrels: the minnesingers

were highly-cultivated amateur musicians, whilst the meistersingers were the professional minstrels. In the well-known advice to a jongleur by De Colenson, who died in 1211,

it is mentioned that a skilful jongleur

should play on the citole as well as on the mandore

and monocnord. Chaucer,

in his Knight’s Tale (1375), alludes to “a citole” in the hands

of a fair dame; whilst Wickliffe writes of “harpes and sitols, and

timpans”. (2 Samuel VI.) The citole was a form of cruit, and the name seems derived from cithara,

although it may be more immediately from cither. Strangely enough

the late Mr. Hipkins gives it as from cistella = a small box, meaning

a box-shaped psaltery, although he admits that the name probably

indicates the rota. It continued in use as late as 1545,

and may be regarded as a high-class crowd or crotta. Edward

III had a citoler in his band of music, as also a fidler; and in

the Squyr of Lowe Degre, written circ. 1480, it is alluded

to under the name of sytolphe, whilst among instruments of the harp

genus are mentioned the getron, santry, rote, and ribible. CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH, SCOTCH AND IRISH HARPERS

Under King Richard II, in 1380, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, erected

a court of minstrels at Tutbury, in Staffordshire, and granted a

charter empowering the minstrels to elect annually a “King of the

Minstrels”, as also four assistants, “to preside over the institution

in Staffordshire, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, and Warwick”.

Thomas of Elmham gives an account of the coronation of King Henry V, at

Westminster, in 1413, and he mentions that “the harmony of the harpers

drawn from their instruments, struck with the rapidest touch of

the fingers, note against note, and the soft angelic whisperings

of their modulations, were gratifying to the ears of the guests”.

According to this author, the orchestra consisted of “a prodigious

number of harps in the hall”—no other instrument being mentioned.

Henry V was undoubtedly a great patron of music, and

was himself a harpist and composer. In 1415 he engaged John Cliff

and seventeen other minstrels to follow him to Guienne, receiving

Harpist forty pounds as their wages (Rymer). In October,

1420, he ordered a new harp to be sent over to him to France; and

there is an entry in the Exchequer Rolls for £8 13s. 4d.—being the

price of two harps—paid to John Bore, harp-maker, of London. It

is assumed that one of the two harps was

for Queen Katherine, whom the English king had married at Troyes,

on June 3rd, 1420. We are told by Rymer, in his Foedera, that Henry V expended a hundred

shillings annually as payment to twelve minstrels, which amount

continued to be paid by his successor. He died at Vincennes, in

August 1422, leaving a name inseparably associated with the victory

of Agincourt. On September 20th, 1467, King Edward IV granted ten marks yearly to William

Eynsham, the King’s Minstrel. In the following year there is allusion

to Robert Hanyes, of Little Malvern, minstrel. About the same time we find an entry on the Patent Rolls referring to Thomas

Briker, harp-maker, and to William Dent, of Selby, harper. In

1474 John Hawkins was King's Minstrel, and in the succeeding year

reference is made to Robert Green, King’s Minstrel. Under Edward IV the Chapel Royal and the King’s Band of Music were put

on a secure basis; and on April 24th, 1469, letters patent were

granted incorporating the Musicians' Company of the City of London

as a perpetual of the Guild of Minstrels, with Walter Haliday as

first Marshal. London Among the harps still existing in Scotland is the famous Clarsach Lumanach,

or Lamont harp, also called the “Lude” harp, supposed to have been

brought from Argyllshire by Lilias Lamont on her marriage into

the family of Robertson of Lude. Not improbably this fine instrument

belonged to Rory dall O'Cahan, a famous Ulster harper, who died

in Scotland about the year 1650. Gunn, in 1807, describes it

as thirty-eight inches high and furnished with thirty-two strings;

and Hudson, in 1840, says that this harp is probably Irish. It certainly

has all the well-known Irish characteristics. One of the loveliest harp melodies at the close of the fourteenth century

is the Irish air “Eibhlin a Ruin” (Eileen, my treasure), known also

as “Robin Adair”. It was composed in 1386 by Carrol O'Daly, a famous

Irish harper. Disguised as a minstrel, O'Daly so captivated Eileen

Kavanagh, of Polmonty Castle, Co. Carlow, that she eloped with him

on the evening of her intended betrothal to a rival lover. In

the song, which he sung with such effect to the accompaniment of

the harp, were two expressions rendered immortal by Shakespeare—namely,

“ducdame” and “cead mile failte” (a hundred thousand welcomes), whilst

the melody itself was much admired by Handel during his stay in

Ireland. Carrol O'Daly, the author and composer of this immortal song, is styled

by the Irish annalists as “chief composer of Ireland, and ollav

(doctor) in music of the country of Corcomroe” (Co. Clare). His

death is chronicled in the year 1405. By the Statute of Kilkenny, in 1367, it was made penal to receive or entertain

Irish harpers or minstrels within the English Pale in Ireland. The

working of this enactment is evident from a licence on the Patent Rolls of

the year 1375 (49 Edw. III.), granting permission to Donal

Kilkenny O'Moghan, an Irish minstrel, to dwell within the Pale.

Two famous Irish harpers of this period were John MacEgan and Gilbert

O'Barden, both of whom died in the year 1369. Ten years later (1379)

is chronicled the death of Gillacuddy O'Carroll, described as “the

most delightful minstrel of the Irish”. In 1433, the Irish Annals place the obit of Aedh O'Corcrain, a remarkable

harper; and in 1438 died Seanchan MacCurtin, described as “historian,

poet, and musician”. An entry on the Patent Rolls of the year

1435 (15 Henry VI) shows that the Statute of Kilkenny was being

disregarded. It is stated that Irish harpers and timpanists (Clarsaghours

and Timpanours) and crowthers (performers on the cruit) “went amongst

the English and exercised their arts and minstrelsies”. In consequence,

the English monarch, as we read, “finding such laws ineffectual,

and his lieges paying grandia bona et dona in exchange for Irish music, commissioned his

Marshal in Ireland to imprison the harpers; and, in order to stimulate

his activity, authorised him to appropriate to his own private use

their gold and silver, their horses, harnesses, and instruments

of minstrelsy”. In the second half of the fifteenth century Irish minstrels were frequent

visitors to Scotland; and in Dauney’s Scottish Melodies there are given several items regarding payments

made to the various musicians at the Scottish Court, e.g. Courts

“April 19th, 1490. To Martin, the clairsach player, and the

other Irish harper, at ye King’s command, 18 shillings. May 30th,

1490. To an Irish harper, at ye King's command, 18 shillings”. In the year 1490 there is an entry in the Annals of Ulster recording the

death of “the son of MacDonnell of Scotland”, at the hands of an

Irish harper named Dermot O'Carbry. Another annalist says that Mac-Donald,

Lord of Eigg, “was slain in treachery at Inverness by Diarmuit Ua

Cairpri”. This affords additional evidence as to the constant visits

of Irish harpers to Scotland. Five years later Hugh roe O'Donnell,

accompanied by his harper, paid a visit to King James IV of Scotland,

“who received the Irish prince with much distinction”. English harpers were also welcomed by King James IV of Scotland, and in

the accounts of the Lords High Treasurers of Scotland there are

a few entries in regard to the sums paid to the “Inglis harparis”. King Richard III was a patron of music, and sanctioned

an enactment for the impressing of choirboys and men for the service

of the Chapel Royal. He gave much largesse to harpers and minstrels,

as did also his successor, Henry VII. (1485-1509). In the

Privy Purse expenses for the year 1498 there is an entry of five

pounds paid as wages to the "three string minstrels,"

and of fifteen shillings to "a string minstrel" for one

month's wages.

An interesting side-light on the grievances of the City of London minstrels

is to be seen in a petition, of about the year 1499, setting forth their dire poverty owing to

the continual recourse of foreign minstrels, and asking that the

Guild might be permitted to levy a fine of three shillings and four-pence on any

manner of foreigner playing on any instrument within said city. It

would seem that the members of this guild had to confine

their teaching to their own apprentices, and these musical apprentices

had to serve a term of seven years. It may here be well to

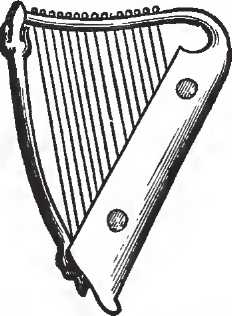

give an illustration of the “minstrel’s harp” of the fifteenth century.

The supremacy of the harp was given a rude shock at this epoch by the spread

of viols, recorders, lutes, virginals, and clavichords; but, above

all, the violin had just come to stay. Still, the harp was very

popular, especially in Ireland. Two famous Irish harpers—Florence

O'Corcoran and William McGilroy—are particularly noticed in the

Annals of Ulster, whose deaths are chronicled in 1496 and 1497 respectively.

Thierry writes: “Every house preserved two harps, always ready for

travellers, and he who could best celebrate the liberties of former

times, the glory of patriots, and the grandeur of their cause, was

remunerated with a more lavish hospitality”. John Major (d. 1525)

gives unstinted praise to the Irish harpers, and he sums up his

eulogy in one sentence: “Hibernenses qui in ilia arte praecipui

sunt”. The art of music-printing from movable types, first introduced by Conrad

Fyner, of Esslingen, in 1473, was destined to effect

a revolution in every department of music. Yet, it was not until 1495 that De Worde printed,

in England, the first book with musical notes; whilst it was in

1502 that Octaviano Petrucci began music-printing at Venice. Later

on, in 1530, Wynkyn de Worde issued the first collection

of English songs with music. CHAPTER VIII THE HARP IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY. Many entries in the Irish Annals testify to the fame of harp-making in

Ireland during the first half of the sixteenth century; and Dr.

Petrie describes for us a very beautiful harp which bore the date

1509, but which has, unfortunately, disappeared since 1810. “It

was small”, he writes, “and but simply ornamented, and on the front

of the pillar or fore-arm, there was a brass plate on which was

inscribed the name of the maker and the date—1509”. It is not a little remarkable that the drawing of the harp, or Harffen,

given by Sebastian Virdung in his Musica Getustacht, printed at

Basil, in 1511, is the mediaeval harp of Ireland as generally represented.

The English minstrels had fallen into disrepute at the beginning of the

sixteenth century, as the following extract from Brandt’s Minstrels

“Ship of Fools”, written in 1494, serves to prove:—

“The Furies fearfully sprong of the floudes of hell, Bereft these vagabonds in their mindes so That by no meane can they abide ne dwell Within their houses, but out they nede must go; More wildly wandering than either buck or doe. Some with their harpes, another with their lute, Another with his bagpipe, or a foolish flute”. In 1515, the King’s Minstrels, for having to journey to Cambridge to perform there,

were given seven shillings; and a similar payment was given

them a few years later. Henry VIII was a musician and composer,

and, in 1526, his Band of Music consisted of a harp, two viols,

a fife, three lutes, four drumslades, three rebecs, three taborets,

ten sackbuts, and fifteen trumpets. In 1530 there was a slight

change in the constitution of this band, as a virginal and three

minstrels were added. Under Edward VI, in 1547, a bagpipe was

included, whilst the number of viols was increased to seven, and

we also find a Welsh minstrel. Polydore Vergil, in his History of

England, in 1534, writes thus of Irish harpers:—"Cujus

musicae peritissimi sunt; canunt enim tum voce tum fidibus

eleganter, sed vehementi quodam impetu, sic ut mirabile sit in tanta

vocis linguaeque atque digitorum velocitate, posse artis numeros

servari, id quod illi ad unguem facuint”. This passage fully confirms

the unrivalled skill of the Irish harpers, especially in the difficult

matter of accompaniment. Vergil marvels at the “wonderful sympathy

between voice and strings”, notwithstanding “the surprising rapidity

of execution by the fingers”; but, as he adds, “this the Irish harpers

do to a nicety”. About this time it was enacted: “That noe Irish

minstralls, rymers, ne bardes, be messengers to desire any goods

of any man dwelling within the English Pale”, upon pain

of “forfeiture of all their goods, and their bodies to be imprisoned

at the King’s will”. In 1537 Robert Cowley, Collector of Customs

in Ireland, wrote to Secretary Cromwell that “harpers, rhymers,

Irish chroniclers, bards, etc., commonly go with praises [elegies]

to gentlemen in the English Pale, praising in rhymes”, etc. The

two most famous Irish harpers of this period were Bryan O'Keenan

and Edmond O'Flynn, whose deaths are duly chronicled in 1537 and

1553 respectively. Foreigners were again a trouble to the musicians of the city of London

in 1555, and, accordingly, a decree was issued forbidding

“foreign minstrels” to exercise their art within the city,

under a penalty of 3s. 4d. About this time flourished a celebrated Neapolitan harpist and composer,

Giovanni Leonardo Primavera, known as “dell Arpe”, from his extraordinary

skill on the harp. He published several volumes of madrigals

and canzonets between the years 1560 and 1573, printed at Venice.

In 1563 we meet with the first Elizabethan enactments against harpers in

Ireland, the reason alleged being that “under pretence of visiting,

they carry about privy intelligence between the malefactors in the

disturbed districts”. Ten years later, a Westmeath harper, Richard

O'Malone, was pardoned, as appears from the Fiants of Elizabeth.

Very different was the attitude of the Queen towards Welsh harpers.

We read that by a commission, dated May 26th, 1567, an Eisteddfod

on a grand scale was held at Caerwys, at which twenty harpers assisted.

The oldest specimen of a harp connected with Scotland is the celebrated

“Queen Mary2 harp, said to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots,

and to have been presented by her to Beatrix Gardyn, of Banchory,

in 1563. Whatever opinion may be formed as to the exact date of

this instrument, it is almost certainly of Irish origin, and has

all the characteristics of an Irish harp of the sixteenth century.

It is 30 inches high, and measures 18 inches from back to front,

being furnished with twenty-nine brass strings, subsequently increased

to thirty. As became a royal harp, it was richly ornamented, being

embellished with the portrait of the unfortunate Scottish Queen,

and with the royal arms, which, however, were stolen in 1745. On

March 12th, 1904, this harp was sold by auction in Edinburgh, and

was acquired for eight hundred and fifty guineas by the Antiquarian

Museum of that city.

An English Jesuit, William Good, who taught a school at Limerick in 1564,

thus writes of the Irish people:—"They love music mightily, and, of all instruments,

are particularly taken with the harp, which, being strung

with brass wire and beaten with crooked nails, is very melodious”.

Between the years 1570 and 1576 various commissions were issued by Queen

Elizabeth in Ireland to “banish all Irish harpers”, etc.; and, in

1576, the Privy Council issued stringent orders against “rhymers, harpers, and

other Irishmen” within the English Pale. Four distinguished harpers

of this period were Donogh MacCreedan, Thady Creedan, Bryan MacMahon,

and James O'Harrigan. A little later flourished Donal MacNamara

and Donal O'Heffernan. However, one harper is especially lauded

by Stanihurst in 1580—namely, Richard Cruise :— “In these days lived Cruise, the most remarkable harper within the memory

of man. He carefully avoids that jarring sound which arises from

unstretched and untuned strings; and, moreover, by a certain method

of tuning and modulating, he preserves an exquisite concord, which

has a surprising effect upon the ears of hearers, such that one

would regard him rather as the only, than the greatest, harper”.

From Derricks’ Image of

Ireland, “made and devised anno 1578”, dedicated to Sir

Philip Sidney, we can form an idea of the ordinary wandering Irish

harper of the period.

The instrument somewhat resembles that seen on the crowned harp badge of

Ireland on the great seal of Queen Elizabeth. In 1581, pardon was granted to three harpers—namely, Mac Loughlin roe O'Brennan,

Walter Brenagh (Walsh), and Donogh O'Creedan, as recorded in the

Fiants of Elizabeth. Vincenzo Galilei, writing in 1583, says:—"I had an opportunity,

a few months since (by the civility or an Irish gentleman), of seeing

an Irish harp, and after having minutely examined the arrangement

of its strings, I found it was the same which, with double the number,

was introduced into Italy a few years ago, though some people here,

against every shadow of reason, pretend they have invented it, and

endeavour to make the ignorant believe that none but themselves

knew how to tune and play on it”. He goes on to say that the compass

of the harp is fifty-eight strings, comprehending four octaves and

one tone, in the manner of keyed instruments—the lowest string being

“double C in the bass, and the highest D in alt”. Unfortunately,

he then goes in for a method of tuning on the Pythagorean system,

and attacks Zarlino very caustically. This attack he follows up

in a second edition of his Dialogo, published at Florence, in 1602.

Galilei definitely states that from the harp is

derived the harpsichord, and this “by reason of the resemblance

in name, in form, and in the numbers, disposition, and materials

of its strings”. The English name “harpsichord” is the self-same

as “Arpicordo”, with the introduction of the sibilant. An examination

of the two oldest dated harpsichords (of the years 1521 and 1531)

proves them to be, as Galilei describes, merely variants of the

“Arpa giacenti”, or “horizontally-placed harp”, and were of

about four octaves in compass. This view is also held by Kircher.

About the year 1585, William Bathe, a young Dublin student at Oxford (author

of the first standard English work on the Art of Music), presented

Queen Elizabeth with “a harp of new device”, as is recorded in the

State Papers. Strange to say, notwithstanding the Queen’s

enactment against harpers, she herself kept an Irish harper named

Donal, and had harps in her Band of Musick. From the Cecil

manuscripts we learn that on September 4th, 1597, the Countess of

Desmond presented Sir Robert Cecil with an Irish harp. As maybe

expected, Shakespeare makes some allusions to the harp. Ophelia's

song in Hamlet was originally sung to a harp, as is evident

from the fact that the two bars of symphony are now sung to the

words: “Twang, lang, dillo dee.” Bacon, in his Sylva Sylvarum

says: “The harp hath the concave not along the strings but across

the strings; and no harp hath the sound so melting and prolonged

as the Irish harp”. Again, he refers to the Irish harp: “And

so, likewise, in that music which we call broken music or consort

music, some consorts of instruments are sweeter than others—a

thing not sufficiently yet observed: as, the Irish harp and bass

viol agree well; but the virginals and the lute, or the Welsh harp

and the Irish harp, or the voice and pipes alone, agree not so well”.

As an instance of an “orchestra” at this epoch, it may be well to mention

that in the “Ballet Comique de la Royne”, performed at the chateau

de Montiers, in 1581, on the occasion of

the wedding of the Duc de Joyeuse and Margaret of Lorraine, the

following instruments were included: “Harps, lutes, hautboys, flutes,

cornets, trombones, viole di gamba, ten violins, and a flageolet”.

However, no combination of these instruments was attempted, as we

read that “the performers were divided into ten bands”, and, for

particular scenes, violins played alone,

whilst in another scene harps and lutes played. What may be regarded

as the first commencement in the history of the modern orchestra,

was the band or concert at a double royal wedding, at Ferrara, in

1598, when the music consisted of a combination of lutes, double

harps, and viols. It is remarkable that although the harp is not scored for in Euridice,

nor yet in La Rappresentassione

dell' Anima ed il Corpo—both produced in the same year (1600)—this

omission was supplied, a few years later, in Orfeo. Monteverde,

in this opera, employed the large Irish double harp for the chorus

of nymphs. In all, he scored for thirty-six instruments, a veritable

Wagner in posse; and his Prelude is an embryo of the Introduction

to the Rheingold. CHAPTER IX THE IRISH HARP UNDER JAMES I. During the year 1601 ten Irish harpers were pardoned, as was also a famous

harp-maker, Tadhg O'Dermody, whose son, Donal, was the maker of

the still preserved “Dalway” harp. In the following year nine

harpers were received into favour, as appears from the Fiants of

1601 and 1602. Two notable harpers, who were also composers—John

and Harry Scott—flourished at this date, of whom Bunting makes mention. Captain Barnaby Rich, in his New Description of Ireland, in 1610, says:—"The Irish have harpers, and those are so reverenced

among them that in the time of rebellion they will forbear to hurt

either their persons or their goods; . . . and every great man in

the country hath his rhymer and his harper”. The greatest harper under King James was Rory dall O'Cahan, who spent most

of his life in Scotland, between the years 1601 and 1645. In

1603, in proof of his reconciliation with Lady Eglinton, he composed the lovely

air, “Tabhair dham do lamh” (“Oh, give me your hand”), which is

also known by its Latinised title of “Da mihi manum”."It has

been printed by Bunting and Dr. Crotch. So popular did this

air become, that King James sent for the composer to play it for

the Scottish court. He is best known as the composer of numerous puirts or ports—that is, lessons

or airs for the harp, e.g.

“Port Gordon”, “Port Athol”, “Port Lennox”, etc.,

generally named after the persons for whom they were composed. In

the Straloch MS. (dated 1627-29) appears “Rory dall’s Port”, but

there is a different air of the same name in Playford’s Dancing Master. The late Mr. John Glen, in his Early Scottish Melodies

(1900), dismisses the Irish origin of this air thus: “It is a matter

of indifference who Rory dall was, or who composed the tune. We

have not found it earlier than the two sources named” —that is,

Oswald and Walsh, in 1757. The real fact is that “Rory dall’s Port”

was in print in 1670, and it was undoubtedly composed by the Irish

harper. Rory is also credited with the composition of the air, “Lady Catherine

Ogle”, but he certainly composed the exquisite harp-melody known

as “An bacach buidhe”, or “The Lame Yellow Beggar”. He died at

the house or Lord Macdonald, leaving hat nobleman his harp and tuning-key. Dr.

Johnson, in his Tour to the

Hebrides (1773), tells us that a valuable harp key, finely ornamented

with gold and silver, and with a precious stone, worth eighty to

a hundred guineas, was then in possession of Lord Macdonald, who

presented it to Echlin O'Cahan. It is worth noting that Sir Walter

Scott introduces Rory dall as the musical preceptor of Annot Lyle,

in his Legend of Montrose. In the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book are some Irish airs, including two harp-melodies,

not later than the year 1570. One of these, “Cailin og a stuair

me”, derives an added interest from the fact that it is quoted by

Shakespeare in william Henry the Fifth (Act II. Sc. 4); and the

song to which it was sung was printed in A Handful of Pleasant Delites,

in 1584. The air is in William Ballet’s Lute

Book, a valuable musical manuscript, circ.

1590, now in Trinity College, Dublin. As a proof of the estimation in which Irish harps were held at this time,

there is an entry in the State papers, under date of March 8th,

1606-7, in which Sir John Egerton, son of the Lord Chancellor of

England, writes to Sir John Davies, Attorney-General for Ireland,

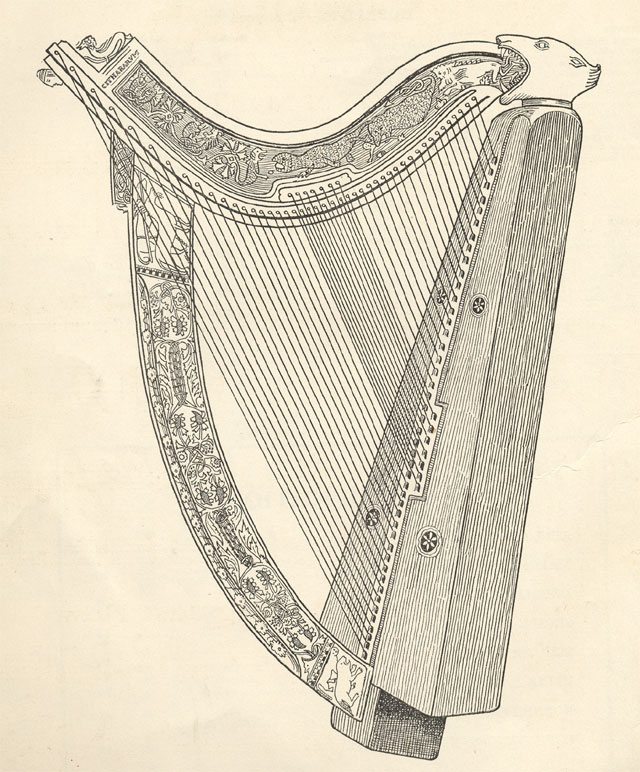

“reminding him of his Irish harp”. There is still preserved a splendid Irish harp, dated 1621, of which a

cast is in the South Kensington collection. This harp was made for

Sir John Fitzgerald, of Cloyne, Co. Cork, but is generally known

as the “Dalway” harp, as the instrument has been for two centuries

in possession of the Dalway family of Bellahill, near Carrickfergus,

Co. Antrim. Bunting gives a long account of it in his second volume

of ancient Irish music (1809), but he fails to identify the maker,

whose name appears as “Donatus Alius Thadei”. The harp-maker is

none other than Donnchadh mac Tadhg O'Dermody, whose father received

pardon in 1601, as previously mentioned. Of a surety, the Fitzgerald (Dalway) harp deserves the title of “queen

of harps”, which is engraved on it in Latin: “Ego sum Regina cithararum”.

The arms of the owner (Sir John FitzEdmund Fitzgerald) are elaborately

chased on the front pillar, and, as Bunting adds, “every

part of the instrument is covered with inscriptions in Latin

and in the Irish character”. “By the pins, which remain almost entire, it is found to have contained

in the row forty-five strings, besides seven in the centre, probably

for unisons to others, making in all fifty-two, and exceeding the

common Irish harp by twenty-two strings. In consequence of the sound-board

being lost, different attempts to ascertain its scale have been

unsuccessful. It contained twenty-four (recte twenty-two) strings

more than the noted harp called Brian Boromha’s, and, in point of

workmanship, is beyond comparison superior to it, both for the elegance

of its crowded ornaments, and for the general execution of those

parts on which the correctness of a musical instrument depends.

The opposite side is equally beautiful with that of which the delineation

is given; the fore-pillar appears to be of sallow, the harmonic

curve of yew”.

Though the original sound-board is missing, a restoration has been effected, and a cast of the restored instrument, as above given,

is in the National Museum, Dublin. One of the inscriptions on the

harmonic curve has thus been translated from the Irish by O'Curry:—

“Giollapatrick MacCreedan was my Musician and Harmonist; and if

I could have found a better, him should I have, and Dermot MacCreedan

along with him, two highly accomplished men, whom I had to nurse

me. And on every one of these, may God have mercy on them all”.

In 1614, there is reference to a harper, Tadhg O'Coffy, who was in the

service of Dr. Geoffrey Keating, author of the Forus Feasa ar Eirinn

(History of Ireland), and to whom Keating addressed a beautiful Irish

poem of nine stanzas. About the same time

we find William FitzEdward Barry, a blind harper, as a retainer

of Lord Barrymore; and in 1620, Daniel O'Cahill was harper to Viscount

Buttevant.

Between the years 1622 and 1625 Father Robert Nugent, S.J., made considerable

improvements in the Irish harp. This accomplished Jesuit was

a cousin of Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare, who, in 1634, gave him

Kilkea Castle, Co. Kildare, for a novitiate of his order. His improvements

mainly consisted in having a double row of strings extended along

the framework of the harp, giving two strings to each sound, which

produced a rich and sonorous quality of tone. He also succeeded

in affording increased facilities for the uninterrupted progression

of the passages with either hand. The full Latin text detailing

these improvements is in Lynch’s Cambrensis Eversus. On the great seal of King James I, as will be

seen from the subjoined illustration, the Irish harp appears upon

the third quarter of the royal shield, as well as on the reverse,

as a badge, crowned. The type of harp is almost the selfsame as

that of the “O'Brien” harp. It was in the reign of King James, too, that the Irish harp was quartered

in the royal arms—that is, a gold harp, with silver strings, on

a blue ground. The Deputy Earl Marshal of England was not enthusiastic

over the matter of having the Irish harp quartered in the royal

arms, and he quaintly observed that "the best reason for the

adoption of the harp was that it resembled Ireland itself in being

such an instrument that it required more cost to keep it in tune

than it was worth." In the King’s Band of Musick,

in 1628, we find one harp employed, in union with eleven violins,

evidencing the growing popularity of the violin.

CHAPTER X THE WELSH TRIPLE HARP. Early in the seventeenth century the Welsh triple harp assumed its developed

stage. Père Mersenne, in 1632, describes this form of harp,

and assigns it a compass of four octaves, with seventy-five strings.

Subsequently we find the Welsh harp comprising ninety-seven strings,

namely, thirty-six bass strings, twenty-six treble strings, and

thirty-five middle strings, tuned from double C in the bass to C

in alto. However, Bingley in his History of North Wales says that

the three rows contain ninety-eight strings, divided as follows:— “Thirty-seven on the right, or bass; twenty-seven

on the left, or treble; and thirty-four in the middle, for the semitones”.

As the two outer rows are diatonic and are tuned in unison, it will

be seen that the Welsh triple harp is merely an evolution of the

Irish double harp. According to Vincenzo Galilei (1589) the Italian

“arpa doppia” was introduced from Ireland, and the only difference

between the Irish double harp and the Italian was that the latter

instrument was furnished with catgut strings instead of brass. The

comparatively modern Welsh triple harp has a third or middle row

of strings containing the sharps and flats—thus rendering the instrument

available for the diatonic and chromatic scales. In Evelyn’s Diary, under date

of June 13th, 1649, we get a glimpse of a Welsh harper named Carew.

The diarist writes as follows:— “I dined

with my worthy friend, Sir John Owen, newly freed from sentence

of death, among the lords that suffered. With him came one

Carew, who played incomparably well on the Welsh harp”. From Pepys, the better-known diarist, we learn of the sad end of Evans,

the Welsh harper of the Restoration epoch. Writing on December

19th, 1666, he says:— “Talked of the King’s family

with Mr. Hingston, the organist. He says many of the musique

(King’s Band of Music) are ready to starve, they

being five years behind-hand for their wages: nay, Evans, the famous

man upon the harp, having not his equal in the world, did the other

day die for mere want, and was fain to be buried at the alms of

the parish, and carried to his grave in the dark at night without

one link (torch), but that Mr. Hingston met it by chance, and did

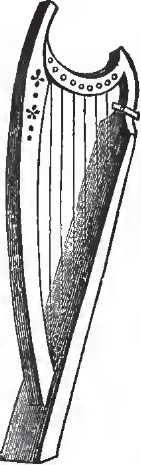

give twelve pence to buy two or three links”. The subjoined illustration will give the reader a good

idea of the Welsh triple harp.

We have stated that the Welsh harp has a triple row of strings, the inner

row being for the accidentals. But it is rather a difficult instrument

to handle. First of all, as the strings on the right-hand side are

for the bass, the tuning has to be effected

with the left hand, and, for the same reason, the instrument has

to be held on the left shoulder, and performed on with the left

hand in the treble; secondly, it is not easy to play accidentals

on the middle or inner row of strings, especially in allegro movements,

or passages that require to be played with rapidity. As Thomas

says, “it is the only instrument of its kind that has ever been

known with the strings on the right side of the comb”, one reason

being that otherwise the player would not have a full view of the

strings. It is remarkable that the first published Tutor for the Welsh triple-string

harp appeared only three years ago (November 1902). Mr. Parry, of

78 Granby Street, Liverpool, after a search of fourteen years discovered

the long-lost MS. prepared by Ellis Roberts (Eos Meirion), harpist

to the Prince of Wales, who died in London, December 6th, 1873.

Its publication is due to the Hon. Augusta Herbert, of Llanover

(Gwenyneu Gwent yr Ail), under the editorship of Dr. Charles Vincent,

and the hope is expressed “that as there exists no longer the excuse

of having no book of instruction for the playing of the 'Delyn Dair-Rhes',

that great and rapid progress will be made in the use of the unique

national instrument of our country (Wales)”. Following the preface

is a long quotation from Edward Jones (1794), the important feature

of which is the arrangement of the ninety-eight strings. It may

be added that the triple harp is tuned in the key of G of the treble

clef, proceeding by fifths and octaves alternately. The present

compass of the instrument extends to five octaves and one note.

CHAPTER XI CROMWELL AND THE IRISH HARP. Under King Charles I, the Irish harp was even more fashionable than in

the preceding reign, and no better proof of this need be adduced

than the publication of a book of motets, in London, in 1630, by

Martin Pierson, Mus. Bac, Master of the Children of St. Paul’s Cathedral—remarkable

as being the first printed work in which tunes were arranged for

the Irish harp. There is a letter from the Earl of Cork, Lord Justice of Ireland, dated

October 14th, 1632, sending an “Irish harpe” as a present to the

Lord Keeper, accompanied by a “runlett of mild Irish whiskey”. M. Boullaye le Gouz, writing in 1644, says that “the Irish are very

fond of the harp, on which nearly all play, as the English do on

the fiddle”. This popularity of the harp continued during the

Confederate period—that is, from 1644 to 1648. It is worthy

of note that Archbishop Laud (who was executed in January 1645)

had an Irish harp, which he bequeathed to John Cobbe, the organist.

According to the testimony of Archdeacon Lynch, in his Cambrensis Eversus, the Cromwellians in

Ireland not only destroyed organs, but also harps. As to organs,

there is ample evidence of their Archdeacon destruction by the Puritans

in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Cashel, and elsewhere. But their rage

seemed specially directed against the national instrument. “They

broke all the harps they could find throughout Ireland”; and so

violently did they act in the matter of harp-breaking that Lynch

was of opinion that “within a short time

scarce a single instrument would be left in Ireland”. Lynch (who is a contemporary witness) was so impressed with the idea that

not a harp would survive the universal destruction of the national

instrument in Ireland at the hands of the Cromwellians, that he

entered into the minutest details regarding the harp,

believing that nothing but a merciful Providence could avert

the complete annihilation of the clairsech. “The barbarous

marauders”.m he writes, “vent their vandal fury on every harp which

they meet, and break it in pieces”.

Here it is interesting to give an illustration of the Arms of Ireland in

the time of Cromwell. In the Great Seal of the Lord Protector we

find an elaborately-designed Irish harp, having the family arms

of Cromwell, as here given. One of the most famous Irish harpers of the Puritan régime was Pierce Ferriter,

of Ferriter’s Castle, Co. Kerry, popularly known as the “gentleman

harper”. He headed a band of troops to defend his property,

but surrendered on condition of quarter for his men and himself.

Notwithstanding this, he was executed at Killarney in 1652. One

of his most prized possessions was an exquisite harp which had been

given him by Edmond mac an daill, of Moylurg,

Co. Roscommon, on which he wrote an Irish poem in twenty-six stanzas,

describing the corr (harmonic curve or cross-tree), the lamhchrann

(front pillar), and the com (sound-board), with the names of the

designer, maker, and decorator. From Ferriter’s poem on the harp we can quite understand the importance

attached to the construction of the instrument, but he specially

dwells on the wealth of ornamentation wont

to be lavished on good harps. His pet harp was decorated with

gold by Partholan mor MacCathaill, and was “bound and emblazoned” by Benglann. Under date of January 25th, 1654, Evelyn writes:—

“Came to see my old acquaintance and incomparable player on the

Irish harp, Mr. Clarke. He is an excellent musician. Such

music before or since did I never hear, the Irish harp being neglected

for its extraordinary difficulty; but, in my judgment, it is far

superior to the lute itself, or whatever speaks with strings”. CHAPTER XII. THE HARP UNDER CHARLES II As is well known, at the Restoration, the gloom of Puritanism was dispelled,

and Charles II requisitioned twenty-four instrumentalists at the

Chapel Royal, with Thomas Baltzar as leader. The harp was still

popular, though being steadily ousted by the violin and spinet.

Some of the greatest scholars took up the Irish harp as a serious

study, and Dr. Narcissus Marsh, Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford,

in 1662, was wont to have “a weekly consort of instrumental music,

and sometimes vocal, in his chamber, on Wednesdays in the afternoon,

and then on Thursdays, as long as he lived in Oxford”. He wrote

a work on the harp, the manuscript of which is now in Marsh’s Library,

Dublin. Evelyn, under date of November 17th, 1668, thus writes:—

“I heard Sir Edward Sutton play excellently upon the Irish harp. He

performs genteelly, but not approaching my worthy friend Mr. Clarke,

who makes it execute lute, viol, and all the harmony an instrument

is capable of. Pity it is that it is not more in use; but, indeed,

to play well takes up the whole man, as Mr. Clarke has assured me,

who, though a gentleman of quality and parts, was yet brought up

to that instrument from five years old, as I remember he told me”. We can form a tolerable idea of the “orchestra” of the Restoration period

from an entry in Evelyn’s Diary in regard to

the Portuguese band of music that accompanied Catherine of Braganza,

Queen of Charles II., in 1662. He thus writes:—

“I heard the Queen's Portugal musiq, consisting of pipes, harps,

and very ill voices”. But we must not be so surprised at this, for

even Alessandro Scarlatti, in his oratorio of St. John the Baptist,

in 1676, employed two solo violins and violoncello, del concertino,

and a large body of ripieni violins, tenors, and basses, del concerto grosso, for his double orchestra.

In 1664 appeared a volume of Services and Anthems by Rev. James Clifford,

having a frontispiece, in which King David is represented playing

on a six-stringed harp. The following lines are printed beneath

the picture of the Royal Psalmist:— “See here the sacred harp with well-tun'd string, Skilfully touched by a most pious king; Of whose great actions after God's own heart: This is recorded too, he played his part”. It would seem that about this time Sir Samuel Moreland invented a new form of harp, but no particulars

have survived, save for the entry by Evelyn, in 1667, who mentions

Moreland’s invention of “a new harp”. To this same philosopher-musician

must be credited the speaking-trumpet, and a mechanical harpsichord,

worked on the principle of “a wheel and a zone of parchment”, thus

anticipating the Angelus, Cecilian, Pianola, etc.

The crowned-harp badge of Ireland, on the Great Seal of King Charles II,

is the development of the symbolic angel form of harp; and, as may

be seen in the accompanying illustration, is the same as still used

in the arms of Ireland. A fine Irish harp is still preserved, known

as the “Kildare” harp, inscribed “R. F. G., 1672”. This beautiful

instrument, still preserved at Kilkea Castle, Co. Kildare, was formerly

the property of Robert FitzGerald, second son of George, sixteenth

Earl of Kildare, hence the name. Apparently

it was manufactured for this nobleman in 1672, and his death is

chronicled in January 1698.

This love of the harp by the Irish nobility of the Stuart period is alluded

to in a description of Ireland, printed in London in 1673, as follows:— “The Irish gentry are musically disposed, and, therefore,

many of them play singular well upon the Irish harp”. Seven years

later, Dineley, in his Tour of Ireland, says: “The Irish are at

this day much addicted on holydays, after the bagpipe, Irish Harp,

or Jew’s Harp, to dance after their country fashion—that is, the

Long Dance”.

There is another beautiful Irish harp of this period, known as the “Fogarty”

harp, having belonged to Cornelius O'Fogarty, of Castle Fogarty,

in 1684. An unsatisfactory drawing of it appeared in the Dublin

Penny Journal, in 1838, and it was stated as then in the possession

of James Lenigan, Esq., of Castle Fogarty. It contains thirty-five

strings, and is now the property of Lieut.-Col. J.

V. Ryan-Lenigan, of Castle Fogarty, near Thurles, Co. Tipperary.

Among the Irish harpers of the period 1660-85, the most celebrated were

Myles O'Reilly, Thomas Connellan, and Laurence Connellan. Thomas

Connellan was a composer as well as a performer, and a number of

his harp-melodies are still popular. He lived over

twenty years in Scotland, a worthy successor to Rory dall O'Cahan,

and many of his airs have been claimed as Scotch. He returned to

Ireland in 1689, and died in 1698. Dr. Narcissus Marsh (of whom I have previously made mention) was appointed

Provost of Trinity College, Dublin, in 1678, and he introduced the

custom of “a weekly consort of music” in Dublin University—the harp

being in evidence. Marsh played the harp very well, but he also

practised the bass viol. In a remarkable paper on “Acoustics”, which

he read before the Dublin Philosophical Society in 1683, he suggested,

inter alia, the term Microphone. It must not be forgotten that the great composer, Scarlatti, was known

as a harpist in his early years—that is to say, from 1673-83. The ingenious device of a Tyrolese, at this epoch, was destined to revolutionise

the art of harp-playing. This device consisted of little hooks,

or crooks of metal, screwed into the neck of the harp, which, being

turned down, produced the required semitones. The disadvantage under

which even the most accomplished player on the harp laboured, by

reason of the diatonic nature of the instrument, suggested to a

musical son of the Tyrol a plan whereby chromatic intervals could

be played. There were two notable defects in the “hook” system. The first was

that one hand was temporarily lost to the performer when engaged

in placing or releasing the crook. A second defect was owing

to the fact that only one string (and not its octave) was

affected by the mechanical arrangement. Still, the hooks paved the

way for the pedal harp. CHAPTER XIII TURLOGH O'CAROLAN. Turlogh O'Carolan occupies a very high place among Irish harpers, and his

name has been immortalised by Goldsmith. Born at Newtown, Co. Meath, in 1670, he became blind in his twenty-second

year, and having displayed much proficiency on the harp, he was

provided with a horse and an attendant by his Early patroness, Madame

MacDermot of Alderford House, Co. Roscommon. Thus equipped,

he began the role of professional harper in 1693, and made his début

at the hospitable mansion of George Reynolds, Esq., of Letterfyan,

where he composed the words and music of “The Fairy Queen”. This was followed by

“Planxty Reynolds” and “Grace Nugent”. From 1694 to 1737 O'CaroIan frequented the houses of the nobles and county

families, and composed over 200 airs, most of which were of a Pindaric

nature, and addressed to his patrons. He was at the zenith of his

fame in 1725, and in 1726 some of his airs were printed in Dublin.

In Daniel Wright’s Arva di Camera, published in London in

1727, there are several airs by O'CaroIan, including “Grace Nugent”

and “The Irish Tune”. Two years later a lovely melody of his was

included in Charles Coffey’s Beggars’

Wedding, adapted to a song entitled “Once I had a Sweetheart”. There is no need to print the harp-melody, composed by O'CaroIan as “The

Princess Royal”, which was printed in 1727, and again in 1730 and

1735. It was so admired by Shield, the friend of John O'Keefe, that

he re-christened it The Arethusa, and arranged it as one of the

songs in his Lock and Key (1796). Hence it has come to be regarded

as an English air, though Mr. Kidson points out properly that Shield

never claimed it—which, of course, he could scarcely have done,

seeing it was printed twenty-one years before he was born. Quite

a dozen of O'Carolan’s airs were introduced into the ballad operas

and musical plays that were in vogue from 1728 to 1748. It is remarkable that O'Carolan was the first Irish composer to break away

from the traditional tune-structure, and from 1725 to 1737 the influence

of Corelli, Vivaldi, and Geminiani is very evident. Geminiani

(who lived many years in Dublin, and died there, in 1762, whilst

on a visit to Dubourg) pronounced O'Carolan as endowed with il

genio vero della musica. Beethoven, in a characteristic letter to Thomson, the Scottish publisher,

says that had O'Carolan got a Continental musical training, he would

have been the greatest ornament of the school of Irish music.

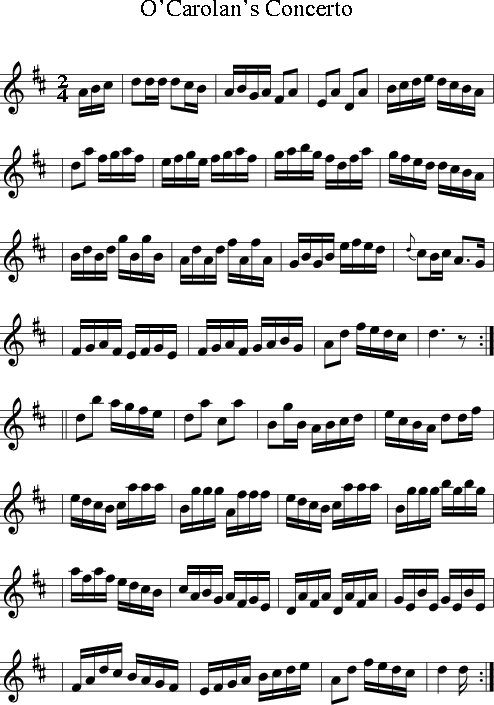

As a specimen of his work when he came under the influence of the Italian

masters, we give here eight bars of his favourite concerto:—

On one memorable occasion, on Christmas Eve of the year 1726, he led a

band of harps at midnight Mass in the oratory of O'Conor at Belanagare,

when the Mass was sung by Bishop O'Rourke, O.F.M. His “Resurrection2

was composed for a Mass on Easter Sunday at Belanagare. Some of

his airs appear in the early Methodist hymn-books. But, though a master of all styles, he shone particularly as the writer

and composer of bacchanalian songs. The best-known examples of this

class are his “O'Rourke's Noble Feast” (English words by Dean Swift)

and Bumpers, Squire Jones. His “Ode to Whisky” and “Receipt

for Drinking” are incomparable of their class. O'Carolan died at the house of his old patroness, Madame MacDermot, at

Alderford, near Boyle, Co. Roscommon, on March 25th, 1738, and was

buried five days later at the east end of the old church of Kilronan,

overlooking Lough Meelagh. He bequeathed his favourite harp to Madame

MacDermot, and it is now (1905) in the possession of the O'Conor

Don, P.C., at Clonalis, near Castlerea. Another of his harps was

taken to London by his son, who, in 1747, published an indifferent

volume of his father’s compositions. Although no monument was erected

over his remains, Lady Louisa Tenison got the cemetery enclosed,

and had the following inscription engraved on the arch of the Irish-designed

gateway:— “Within this churchyard lie the remains of Carolan,

the last of the Irish bards, who departed this life March 25th,

1738. R.I.P.” Lady Morgan presented a splendid bas-relief of O'CaroIan to St. Patrick's

Cathedral, Dublin, which is placed in the north aisle, and which

we have reproduced.

Many of O'Carolan’s airs were adapted by Tom Moore for his Irish Melodies,

e.g. “Planxty Peyton” (“The Young May Moon”), “Planxty Kelly” (“Fly

not yet”), “Planxty Irwin” (“Oh! banquet not”), “Planxty Tyrrell” (“Oh!

blame not the bard”), “Planxty Sudley” (“Oh! the sight entrancing”), and

“Planxty O'Reilly” (“The Wandering Bard”), better known in Lover’s

setting as “Molly Carew”. Other famous Irish harpers, who were contemporaries of O'Carolan, are MacCabe,

MacCuarta (Courtney), Lyons, Heffernan, and Murphy. Lyons was

domestic harper to the Earl of Antrim, and composed some folk melodies,

as well as variations for the harp. Heffernan resided in London

from 1695 to 1725, and was in request as a harpist. John Murphy travelled

on the Continent from 1708 to 1719, and

had the honour of playing for Louis XIV. At a

special performance, at Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin, on February

14th, 1738, Murphy was one of the attractions as a harp-soloist.

He played for some seasons at Mallow, and

died after the year 1753. In addition to O'Carolan’s harp, there are four other Irish harps of this

epoch still preserved. These four instruments are respectively

dated 1702, 1707, 1726, and 1734—viz., “Hempson's” harp, the “Castle Otway” harp,

the “Hehir” harp, and the “Bunworth” harp. The “Hempson” harp was made by Cormac O'Kelly, of Ballynascreen (Draperstown),

Co. Derry, as is evident from the inscription on it:— “In the time of Noah I was green; After his flood I have not been seen; Until seventeen hundred and two I was found By Cormac Kelly under ground; He raised me up to that degree, Queen of Music ye may call me.” The workmanship of the harp is not equal to the “Dalway” harp, and the

instrument passed through many vicissitudes in Hempson’s hands.

On the next page is an illustration of it.

The Castle Otway” harp was also made by Cormac O'Kelly,

and is now at Castle Otway, Co. Tipperary. John Kelly made the “Hehir”

harp in 1726. It had thirty-three strings, and was made of red sally,

and is said to have been five feet high. Walker gives an illustration

of it, drawn by William Ouseley (father of Sir Frederick Gore Ouseley,

Bart., Mus. Doc), the original instrument being then (1786) the

property of Jonathan Hehir. A very fine harp is that known as the “Bunworth”, made by John Kelly

in 1734. It was expressly manufactured for Rev. Charles Bunworth,

Rector of Buttevant, Co. Cork, whose house was ever open to the

wandering harper. After his death, it passed into the possession

of Crofton Croker, his great grandson, and was sold,

in London, in 1854. It is now the property of Rev. F. W. Galpin,

who lent it for exhibition last year (1904) at the Fishmonger’ Hall,

London.

CHAPTER

XIV INVENTION OF THE PEDAL HARP.

|