CHAPTER I.

THE ANTIQUITY OF THE HARP

Early Egyptian harps. Their origin to be traced in the

three-stringed lyre. Harps in Assyria, Babylonia, Uganda, and Persia.

Aethicus of Istria. Heccataeus.

Harps in pagan Ireland. Affinity between the Egyptian and Irish

harp. The Ullard harp. The timpan and ocht-tedach. Greek and Roman harps. The name “harp” of English

origin. How the harp was evolved from the hunter’s bow. High artistic

quality of early Egyptian music.

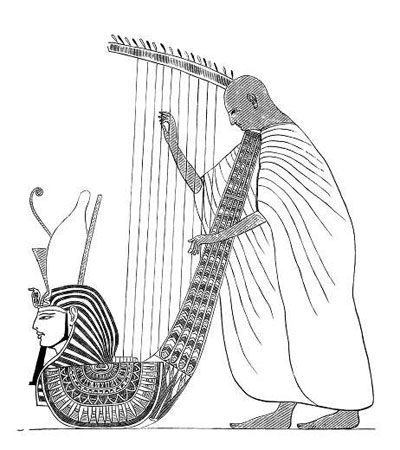

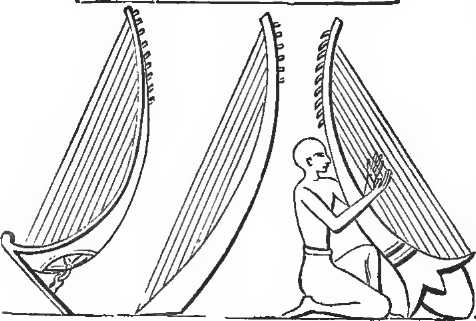

It is a commonplace of musical history that Egyptian

harps have been discovered whose date goes back, to at least, three

thousand years ago. The statements of Bruce and Wilkinson were at

one time regarded as more or less apocryphal, in

regard to the very advanced state of musical culture possessed

by the ancient Egyptians, as illustrated in the representations

of harps from the Temple of Ammon at Medinet-Abou, near Thebes. Pocock and Norden were the first

to announce the ancient drawings of harps at Thebes, but it was

reserved for Bruce to accurately sketch two harps from the fresco

panels in Egypt. Recent researches have amply confirmed the authenticity

of the drawings made by Bruce, and therefore there is no longer

question as to the great antiquity of the harp among the Egyptians.

The instrument was fully developed under King Rameses III, circ.

B.C. 1260, as may be demonstrated by a reference to the drawings

given by Sir G. Wilkinson, especially the magnificent harp from

the tomb of Rameses here illustrated.

FIG. 1.—egyptian harp.

|

|

The harps of the royal minstrels in ancient Egypt were

magnificently ornamented, and were embellished with, the head of

the monarch himself. Herodotus tells us that the favourite song

of the ancient Egyptians was a dirge, “The Lay of the Harper”, which

is beautifully translated in Ancient Egypt, by Rawlinson.

One striking peculiarity of this old-world instrument

is the absence of a fore-pillar. Many

writers have remarked that the Egyptian harps must, of necessity,

have been of very low pitch, inasmuch as

the tension was perforce weak, owing to the want of a fore-pillar,

or harmonic curved bar. This, however, is a fallacy, as, owing to

the artistic construction of the harps, a sufficiently high tension

was obtained. The strings were invariably of gut, and the number

varied from seven to twenty-one, although, in general, thirteen

was the normal number. Under King Thothmes

III., B.C. 1470, harps of fourteen strings were in use.

In height the harps were about six feet, and were elaborately

ornamented, lotus flowers being much in evidence. The rows of

pegs sufficiently attest the method of tuning, whilst the slits

at the back were sound holes, as in the harps of our own

days. Bruce regarded the Theban harps as “affording incontestable

proof that every art necessary to the construction, ornament, and

use of this instrument was in the highest perfection”.

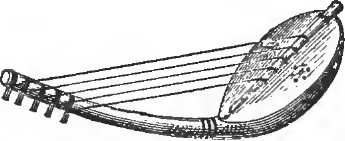

FIG.

2.—A STRINGED INSTRUMENT, SOMETHING BETWEEN A HARP AND A

LUTE. |

|

This highly-finished instrument was undoubtedly the evolution

of the three-stringed lyre, as depicted on the mast of Queen Hatashu's ship, which vessel she sent to the land of Punt,

identified as the south coast of Arabia. The traveller today can

gaze upon the wonderful temple that Queen Hatashu

built in honour of Amen, King of the Gods of Thebes, and can see

on monumental stone the carvings describing, as in a panorama, the

voyage of the five ships. Prominently displayed on the mast of one

of these ships is the three-stringed lyre. Here is an illustration

of such lyres, but with five strings. There is scarcely a shadow

of doubt that the harp was the final stage of the tightly-strung

bow of primitive man, when by accident the stretched string emitted

a musical sound on being plucked by the hunter. From one string

to three strings was an easy transition, and the form of the hunter’s

bow was retained. In the course of years the number of strings was increased, as in the accompanying

illustrations Figs. 3 and 4.

fig. 3.—eastern harp. |

|

Assyria and Babylonia were famed for music from the very

earliest period, and the harp figured prominently in their social

life. The Assyrian harp— like the Egyptian and old Irish—had no

front body was uppermost, whereas in the Egyptian instrument it

was always at the base. The Assyrians appear to have used a plectrum.

Of all ancient peoples Babylonia can claim pride of place.

From the plains of Babylonia came the most advanced culture, as

may be evidenced by the bas-reliefs at the British Museum. A slab

was discovered two years ago at Tello, or Scipurra,

which Mr. St. Chad Boscawen dates as B.C. 2500. This remarkable

“find”, due to the American explorers in Babylonia, is a sculptured

tablet representing musicians, one of whom is seated playing on

a harp of eleven strings.

fig. 4.—ancient harps. |

|

It is not surprising that a people like the Babylonians,

who were fully acquainted with the arch in architecture, should

be so advanced in the art of music.

The Sumerian Plain is regarded by the most recent authorities

as the land of Eden mentioned in the Book of Genesis, and etymologists

are agreed that “Eden” means the “Plain”; that is, the alluvial

plain of Sumeria. Moreover, a hymn of

the Sumerians alludes to the “magical tree of life”growing

in Eden, analogous to what is mentioned in the Bible.

Sargon, B.C. 700, founded a library at Sippara, and the student at the British Museum can feast his

eyes on hundreds of tablets, all testifying to a high degree of

culture. In the Assyrian Room of the British Museum are some of

the sculptured stones brought from the mound of Kouyunjik,

the acropolis of Nineveh, by Layard. Musicians are seen performing

on dulcimers, striking the strings with rods, that instrument

being attached to the waist by a string or ornamental tassel.

In Uganda, as is recorded by Sir Harry Johnston, the

natives still play on a primitive form of harp of eight strings.

An older form of harp, or rather a one-stringed bowed lyre, is also

described by this African explorer, the performer holding the string

between his teeth, and plucking it, somewhat after the manner of

the trump or Jews’ harp.

The Persians, too, had harps, as is attested by some

sculptures on an arch near Kermanshah, north-east of Bagdad. An

Irish traveller, who sketched the drawings in 1807, says that “the

strings of the harp (chang) were completely

visible and the figures were in perfect preservation”. As far

as can be judged from the drawings, which date from about the

sixth century, the size of the instrument was small, and only had

eight to ten strings. It may be added that

from Persia a bowed instrument called the rebab came to Arabia—a

form of violin.

Pre-Christian Ireland certainly had harps, and a

remarkable fact is that these harps were apparently modelled on

those of the Egyptians—that is, having no fore-pillar. All Celticists

are agreed that the pagan Irish were a most cultured people,

and had the use of letters long before the advent of St.

Patrick. Aethicus of Istria, a Christian philosopher of about the Aethicus of year 300 made a tour to Ireland from Spain, and describes in his Cosmography that he had examined

the Irish writings or sagas.

The old Irish name for the harp was crott or cruit. Originally a small

instrument of three or four strings, plucked with the fingers, it

is mentioned by an Irish poet who flourished about four hundred

years before Christ. Subsequently this Irish cruit was played with a plectrum, or bow, and is justly regarded

as the progenitor of the crotta (chrotta) and the Italian rota, also of the English crowd and

the Welsh crwth. St. Venantius Fortunatus, about the year 604, thus alludes to the cruit:—

“Graecus achilliaca,

chrotta Britanna

canat”.

This chrotta or cruit was the name for the oldest form of Irish harp, and it

is a mistake to confound it with the modern Welsh crwth. Much ingenuity

has been expended on explaining the above line of St. Venantius

Fortunatus, but it is certain that, originally,

the cruit was the small

Irish harp, called crowd by the English and crwth by the Welsh.

In early mediaeval times this equation of terms was observed; but

somehow or other a quite different instrument in Wales was given

the same name, just as the cornet of the Middle Ages is quite a

different instrument from that of today. Long before the coming

of St. Patrick allusion is made in some of the romantic tales to

the crott, and also

the crott-bolg or harp-bag, whilst the harper was invariably known

as cruitire,

or performer on the cruit.

We learn from Gerbert that

the chrotta

was an oblong-shaped instrument, with a neck and finger-board, having

six strings, of which four were placed on the finger-board,

and two outside it—the two open strings representing treble G with

its lower octave. In fact it was a small harp played with a

bow, generally placed resting on the knee, or on a table before

the performer.

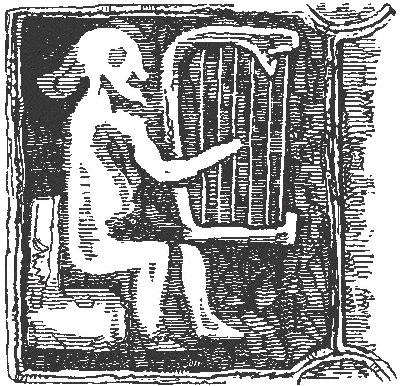

fig. 5.—three-stringed crwth.

|

|

Carl Engel’s view seems correct that the original crwth

was not a bowed instrument but a small harp—in fact, the Irish crott, which in the course of centuries

was adapted as a fiddle-harp. An illustration of the three-stringed

crwth is also to be found in a manuscript in the National Library,

Paris, formerly belonging to the Abbey of St. Martial de Limoges.

This manuscript dates from the eleventh century, and the subjoined

illustration will give the reader an idea of the instrument.

A very early authority for the cruit

in Ireland is Heccataeus, the Egyptian

historian, who gives a short description

of Ireland, about the year B.C. 500. From Booth’s translation the

following brief extract will be of interest:—"They say that Latona

was born here, and, therefore, that they worshipped Apollo above

all other gods.... That there is a city likewise consecrated to

this god, whose citizens are most of them harpers, who, playing

upon the harp, chant sacred hymns to Apollo in the temple”.

From another ancient writer, B.C. 200, we learn that

the Irish children imagined the spirit of song to have had its abode

among the trembling strings of the cruit;

and, in the vision of Cahir Mor (A.D.

100), allusion is made to the “sweet music of the harp”. Again,

in the Dinnseanchus, attributed to Amergin

mac Amhalgaid, circ.

A.D. 540, we read à propos of the

reign of Geide, monarch of Ireland (a.m.

3143), that the people “deemed each other’s voices sweeter than

the warbling of the melodious harp”.

fig. 6.—the ullard harp (a.D. 845).

|

|

The perfected state of the small Irish harp (cruit) in the fifth century may be gleaned from a reference

to the tuning-keyin the Brehon Laws. No

authority can be higher than the wonderful code of laws known as

the Seanchus Mor

(published by the Record Office in six volumes), compiled in the

fifth century, and a special legislation was formulated in the case

of the non-return of a harp or a harp key. The term crann-glésa

literally means "tuning wood," and in case the tuning-key

of the cruit was lent and not returned, a smart penalty was inflicted.

Perhaps the strongest proof of the affinity between the

Egyptian and Irish harp is the still preserved sculptured harp on

the stone cross at Ullard, Co. Kilkenny—wherein

the fore-pillar is absent. Petrie dates the Ullard

harp (which I myself examined in 1888) as of the ninth century,

and was of opinion that the Irish harp was a form of the

cithara, derived from an Egyptian source, thus corroborating the

bardic tradition of the Milesians, as, according to the Irish annalists,

“the Milesians in their expedition from Spain to Ireland were accompanied

by a harper”.

Closely allied to the three-stringed lyre is the Irish

timpan, which was played with a plectrum

or bow, deriving its name from the fact of the belly being drum-shaped. Hundreds

of references to this small instrument are to be met with in

the Irish sagas. The music of it was called a “dump”, and it continued

popular until the close of the seventeenth century. In mediaeval

days the plectrum was superseded by a bow, and the brass strings

were replaced by those of gut. It is referred to by Giraldus

Cambiensis in the twelfth century.

A further development of the three-stringed harp was

the ocht-tedach—that is, the eight-stringed

harp. In a passage of the Book of Lecan,

relative to a King of Cashel in the eighth century, weread:—"On a certain

day when King Felim was in Cashel, there

came to him the abbot of a church, who took his little eight-stringed

harp (ocht-tedach) from his girdle, and played sweet music, and

sang a poem to it” . This passage makes it appear that the

ocht-tedach was attached to the girdle of the performer (as

was the custom of the Egyptians), and it also shows the then prevailing

custom of singing to the accompaniment of the harp.

FIGS. 7, 8.—ANCIENT HARP |

|

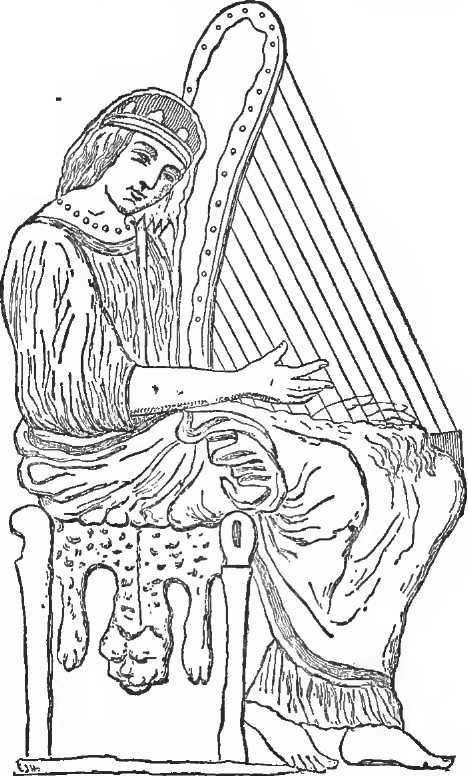

The Greek and Roman harps were also due to an Egyptian

origin, or from an Asiatic source by way of Egypt. There were several

forms of the Grecian lyre, and, of course, similarly with the harp.

Visitors to the British Museum are acquainted with the beautiful

representations of Greek lyres to be seen in that vast storehouse

of knowledge. The Greeks, too, had a trigon, or three-cornered (triangular-shaped)

harp, of which a good specimen is on an Etruscan vase at Munich,

as here given. Terpander, who flourished

B.C. 670, is said to have increased the number of strings of the

lyre from four to seven. The late Roman harps would appear to have

the harmonic curve, containing the harp pegs below (instead of being

uppermost), whilst the sound box—as in the Assyrian harps—was above.

The Kissar, known also as the Kisirka,

or Ethiopian lyre, is the parent of the cithara and lyre. In the

very examples belonging to or the late Mr. T. W. Taphouse,

M.A., of Oxford, the strings are of camel gut. The Kissar

was plucked with the fingers, or else with a horn plectrum, and,

as in the case of the harp, there was much diversity in

regard to the number of strings—the general number being

seven.

FIG. 9.—ANCIENT HARP, COPIED

FROM A GREEK VASE. |

|