| |

CHAPTER 20

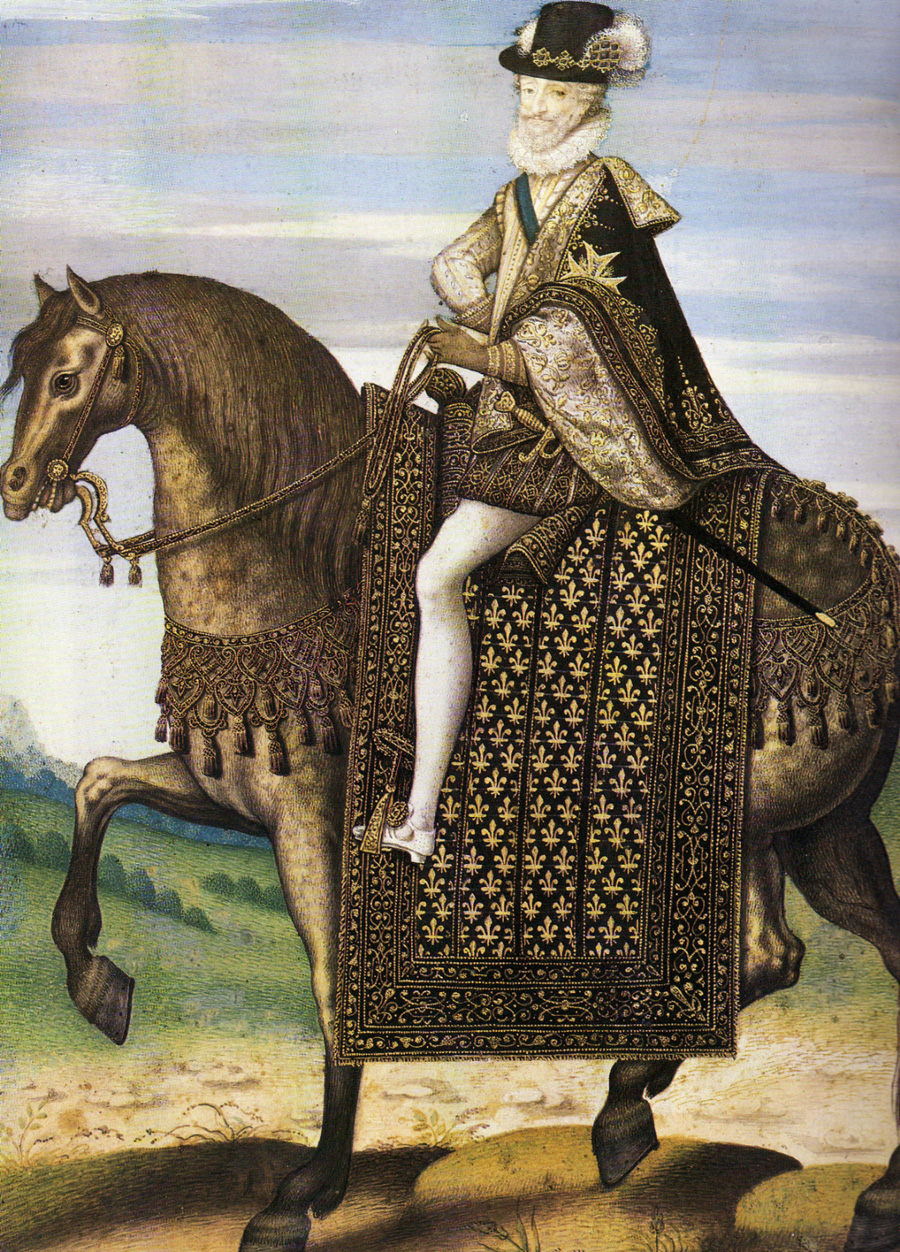

HENRY IV OF FRANCE.

Europe in the XVI century |

|

UPON the death of Henry of Valois, Henry of Bourbon succeeded to a

dubious heritage and a distracted kingdom. His ancestral right to the temporal

throne was clear; but, before a Calvinist could be accepted as Most Christian

King and eldest son of the Church, a new definition of Church and Christian

would be required. As a party leader he inherited all the difficulties which

beset Henry III as well as those of his own position. His opponents commanded

the sympathy of the great majority in France. The organization of their League was effective and all-pervading. The great towns, with few

exceptions, were on their side. The family interest of Guise, though it alarmed

and alienated a considerable part of the French nobility, had grown by fifty

years of active political work to rival the monarchy itself. The Parlements, which during the troubles had arrogated to

themselves an extensive political control, had been captured by the League,

and the royalist minorities had been compelled to secede. The Sorbonne contributed

the prestige of theological authority to combat the claims of a heretic: a

heretic relapsed. The lower clergy threw their considerable influence and

damaging activity on the same side. The most experienced administrators added

the weight of their support; and the rank and file of office-holders shared

the views of the majority. Outside the kingdom, the Pope might be expected to

give moral if not material assistance. The Leaguers were secure of aid from the

most powerful European monarch, and had recognized claims upon his treasury.

Among Henry's possible allies, Elizabeth was cautious and chary, the United

Provinces were embarrassed and exhausted, the German Princes disorganized, divided, and for the most part poor. The King

of Spain had all his resources at his own command, and it was not his habit to

let expenditure wait upon revenue.

But chance had granted one signal opportunity to Henry. In the camps at Meudon and Saint-Cloud were assembled all that was left of

the faithful royalist nobility, all that royal promises and prestige had

availed to collect of foreign assistance, and all that the name of Henry of

Navarre and the credit of the Reformed religion had been able to contribute to

this singular alliance. By the exercise of conspicuous tact, the new King

contrived to propitiate the Catholic nobility (some, like Biron,

by material concessions, others by holding out hopes of conversion) without

alienating the bulk of his Protestant followers. The army which Henry led into

Normandy, though weakened by important defections both on the Protestant and on

the Catholic side, was still the army of a King, not that of a mere party

leader or pretender.

The victories of Arques and Ivry were extorted from fortune by the valor and resource and energy of Henry IV. They gave time for certain favorable influences to sway the balance. The strong

royalist feeling, which still prevailed among the French nobility, was fostered

and strengthened by Henry's personal exploits. The Wars of Religion and the

disgraces and disorders and incompetence of the Valois government had indeed

done much to break down the tradition which the Capet dynasty had painfully and

slowly built up during six centuries. The example of resistance to the royal

authority had been set by the Protestants; but the formation and development of

the League had called forth opinions destructive to the monarchy more

abundantly, if anything, upon the Catholic side. The deposition of an unworthy

King, the elective character of the monarchy, the control of the King by the

Estates, the duty of resistance to tyranny, the justification, in certain

circumstances, of tyrannicide, the doctrine of a

contract between King and people that might be voided by non-fulfillment of implicit conditions or abrogated by the people's

act, the need of constitutional checks and balances, all these were topics which

lent themselves more easily to the champions of the League than to the

Protestants, who were themselves in a minority. Again, the League, with its

democratic organization in the great cities where so

much of its power lay, brought the practice of popular control and popular

government into the political arena; while the Calvinists, in spite of the

democratic aspect of their consistories and synods, were really more conservative

both in theory and in practice than the extremists of the League, and were

ready to rally to a monarchy that offered them tolerable prospects of efficient

protection. Moreover, the subversive doctrines which inspired the abundant

political literature of the time appealed rather to the bourgeois than to the

nobles, who were in fact disgusted and alarmed at the license of the citizens;

and such views found little sympathy among the higher ranks of the clergy.

Everywhere attachment to the King, though dormant, only awaited a favorable occasion to reassert its power. Thus the

monarchical tradition, though shaken by the years of disorder, still retained

its vitality, and came to the support of a King who showed himself worthy of

royalist devotion. The nobility, although their military service was

interrupted and precarious, fought brilliantly and successfully on Henry's

side.

Again, the Gallican sentiment, chartered but not created by the

Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges, and encouraged in a less attractive form by the

Concordat of Francis I, was a force that had hitherto exercised little

influence in the struggle; but the situation was such that a conflict between

national and ultramontane could hardly be avoided. A cardinal point in the

Gallican creed was that the Pope could exercise no temporal authority in France; and papal excommunication, papal deposition of a heretic King, were probable

if not inevitable, and carried vital consequences in the temporal sphere. The Parlements were the home of Gallicanism, and, if any

question arose of the Papacy dictating the choice or the exclusion of a King,

were likely to rise in opposition. Moreover, since the Concordat of Francis I,

the King had controlled all the higher patronage of the Church; and the

prelates, through dependence on the royal favor, had become a royalist body.

Very few Bishops ever joined the League; and at the crucial time of his

conversion episcopal aid and countenance proved of

incalculable value to Henry. So long as Sixtus lived,

his cautious policy avoided anything resembling a rupture. But the violent

policy of Gregory XIV, which appeared to be dictated by Spanish proclivities,

tended to enlist all Gallican sympathies on the royalist side. His monitorials of March 1, 1591, by which Henry was

excommunicated and declared incapable of reigning, were rejected, not only by

the dissident Parlements of Chalons and Tours, but by

a weighty assembly of prelates at Chartres (September 21, 1591).

Finally, there was in France a strong national feeling which contributed

not a little to the ultimate result. The League, although in alliance with

Spain, and in receipt of Spanish subsidies, had before Ivry not shown itself decisively anti-national. The Guises were regarded by many as

foreigners, in spite of their long settlement in France; and the intention of

Henry of Guise may have been to substitute himself for Henry of Valois. But

such designs, if they existed, were prudently masked. In reliance upon foreign

aid up to the battle of Ivry there was not much to

choose between the two sides. Both sides employed foreign contingents, and

relied on foreign subsidies. But after that battle it became more and more

apparent that the cause of the League depended upon the armed and official

intervention of Spain. The blockade of Paris must have ended in the surrender

of the capital but for the march of the Duke of Parma; and similar action

frustrated the siege of Rouen. In the sittings of the Estates of 1593 the

designs of Spain were clearly exposed. Encouraged by the overtures of the

"Seize", the King of Spain put forward the claims of his daughter to

the throne of France. But the Estates, purely partisan as were the interests

represented among them, would not tolerate the proposal in any form. The hopes that Mayenne or the young Duke of Guise may have

entertained were defeated in part by the division of the family interest; but

the Salic Law proved the final and insuperable bar to all the candidates.

The Parlement declared the Salic Law

fundamental, and vital to the interests of the nation. The Estates followed

their lead. Had the Cardinal of Bourbon, only one degree further removed from

the direct succession than Henry himself, lived to secure the adhesion of the

national party, the result might have been different. But, as it was, the

dreams of League theory, that a system of election might be substituted for the

rules of succession under which France had grown to be a nation, were

conclusively relegated to the limbo of the impracticable. For the second time

in history the Salic Law, for all its frame of legal pedantry, proved itself

the safeguard of French national existence, the formula of French independence.

Henry IV (13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610) King of France from 1589 to 1610 and (as Henry III) King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France. His parents were Queen Jeanne III and King Antoine of Navarre. |

|

Conversion of Henry. [1593

Again, the support of Spain, which kept Henry at a standstill for more

than two years after the battle of Ivry, brought

about by an inevitable chain of causation the solution of another problem. Both

before and after his accession Henry had professed his willingness to be

instructed, and had held out hopes that instruction might lead to conversion.

There are some reasons for believing that on the vital question of the Real

Presence his personal leanings were towards the Catholic position. At

Saint-Cloud he had opposed to demands for immediate conversion considerations

of honor. He could not, as King of France, abandon

his religious profession in response to force. The successes of Arques and Ivry seemed to have

indefinitely postponed the prospect of his change of faith. Had he been

successful before Rouen and Paris, no conversion might have ensued. But in 1593

four years' experience seemed to show that the choice lay between indefinite

prolongation of civil war and fulfillment of his

pledge. In what proportions ambition, true patriotism, and genuine conviction

contributed to Henry's decision no man can say. But his subsequent history

shows him a true friend, not only to religious toleration, but also to the

religion which he adopted. Motives of patriotism were fully sufficient to

justify some sacrifice of personal predilection. The reunion of France under a Protestant

King had been proved to be impossible. It had been proved that no King other

than Henry could hope to satisfy the national desire for a natural King. The

conversion of Henry was thus the only hope of France.

But Henry's conversion, though indispensable, was not in itself

sufficient to produce a settlement. Doubts still existed of his sincerity. The

absolution granted to him by the French prelates was only provisional; and

absolution by the Pope was necessary to complete his reconciliation with the

Church. Clement VIII, though his attitude was encouraging, was determined that

the King should knock at the door more than once before he was admitted to the

Church. Meanwhile France had to live; and daily life gave daily opportunities

for the application of minor sanatives. The military

situation remained unchanged. Henry's authority extended little further than

the area dominated by his troops and his allies. In Dauphiné his lieutenant, Lesdiguières, held the field in the

Protestant interest. In Provence the Duke of Épernon,

nominally governing under royal authority, was building up against local

opposition a power neither Leaguer nor Royalist, but private. In Languedoc the Politique Governor, Montmorency, maintained his position,

though the League was still formidable and controlled the Parlement of Toulouse. Montmorency' own attitude was doubtful; and there was reason to

believe that he aimed at establishing independent power. His loyalty was

eventually secured by the gift of the office of Constable. In the country

between Loire and Pyrenees lay Henry's ancestral domains, the lands of Navarre,

Béarn, Foix, Armagnac, Bourbon, and Albret. But the League was strong even here. Bordeaux and

the Bordeaux Parlement were for the League; Poitou

in particular was very evenly divided. North of the Loire Britanny was held by the Duke of Mercoeur with Spanish aid,

not without opposition, but with commanding superiority. Normandy was shared

between the parties; rival Parlements sat at Caen

and Rouen. Picardy was for the League and subject to Spanish influence. In the

East and Centre of France the League had scarcely been attacked. Burgundy

especially was the stronghold of Mayenne's power.

Champagne, under the government of the young Duke of Guise, acknowledged the

League. At Lyons, though the Guisard governor,

Nemours, was on bad terms with the civic community, League influence was

hitherto unimpaired. The work of reconstruction was still to be done.

In long

years of warfare men had almost ceased to desire peace; some, like Biron, were inclined to prolong the war in order that they

themselves might be indispensable; others, like the Seize, feared that peace

would bring retribution; it was first of all necessary that men should be

brought to desire security and repose. For this purpose Henry succeeded in

negotiating a truce, which was concluded on July 31, 1593, for three months,

and afterwards prolonged till the end of December. During this interval the

League began to dissolve. Individuals opened negotiations with the King, and

some minor surrenders actually took place. Lyons rose against Nemours

(September 18) and threw him into prison. One vein of contemporary thought is

represented by the Satyre Ménippée,

part of which circulated in this year, and which in the following was published

in its complete form. Though a partisan production, its exposition of the

selfish aims of prominent Leaguers carried conviction; the line adopted hit

the temper of the time; and the opinion began to spread that the League was

now only perpetuated for personal and political objects. Meanwhile the King

made known his desire for peace; and, when hostilities were renewed with the

new year, it was felt that the fault lay elsewhere, with Spain, with the Seize,

and with Mayenne. Before the truce was ended, Villeroy, the most experienced administrator on the side of

the Leaguers, had declared his defection; and on every side adhesions to the

royal cause were in contemplation.

With the new year similar occurrences became

more frequent. Aix and its Parlement, hostile to Épernon, submitted to the King and carried with them part

of Provence. A fresh revolution took place in Lyons, and the city accepted

terms in February. The condition that the exercise of no religion other than

the Catholic should be permitted in the city showed how far the King was

prepared to go. What better terms could any Catholic city desire? Villeroy and his son finally came over, and brought with

them the town of Pontoise; and d'Estourmel began to negotiate for the surrender of Peronne, Roye, Montdidier, frontier towns

of Picardy, which was completed in April. La Chastre brought Orleans to the royal obedience; Bourges and the remainder of Berry and

the Orléanais soon followed the example. The royal

prestige was considerably enhanced by Henry's coronation with all due forms at

Chartres (February 27, 1594). Rheims was still in the possession of the League,

and precedents existed for this alternative place of consecration; while the

chrism employed was drawn from the Sainte-ampoule of St Martin, scarcely less

holy than that of St Rémi.

Recovery of Paris. [1594

But Paris was not to be regained at the price of a mass. The new

positions acquired by the King enabled him to establish an effective blockade;

and the city soon began to feel the pinch of hunger once more. The Politique party began to raise its head; Mayenne began to feel insecure; he was forced to abandon

himself more and more to the Seize, and to rely upon Spanish troops. The

Governor, Belin, was deposed, and Cossé-Brissac set up in his place. The Parlement began to lean to

reconciliation, and its meetings were prohibited. But agitation and conspiracy

continued, and on March 6 Mayenne left the town.

Freed from his supervision, the King's friends moved forward more boldly; Cossé-Brissac was gained and succeeded in hoodwinking the

Spaniards. On the morning of March 22 the King entered his city and occupied it

almost without resistance. The Spanish garrisons were cut off from each other

and were fain to accept the conditions offered, that they should depart with

bag and baggage. Great skill was shown in all the arrangements; but matters

could not have passed off so quietly had not a considerable revulsion of

feeling taken place. Even in the disorderly and enthusiastic quarter of the

University no serious opposition was met, though the regular force by which the

King was supported on his entry did not exceed the numbers of the Spanish

garrison. A universal amnesty was granted, even to the leaders of the Seize,

though it afterwards became necessary to banish some hundred and twenty of the

most irreconcilable Leaguers.

On the reoccupation of the capital it became possible to begin the work

of reconstruction. During the months of April and May the sovereign Courts, the Parlement, the Chambre des Comptes, the Cour des Aides, were

restored to their lawful constitution and authority. The dissentient members of

these bodies had retired in 1589 to Tours and Chalons, where rival Courts had

been set up. The members of these royalist Courts were now recalled and took

their places peacefully side by side with those magistrates who had issued

their decrees in the service of the League. The Parlement annulled the office of Lieutenant-General, irregularly conferred upon the Duke

of Mayenne. The Sorbonne, and the University as a

whole, made their submission to the King, took the oath of allegiance, and

issued a declaration recognising Henry as the lawful

sovereign of France.

Elsewhere the King began to enter into his heritage. In

Normandy Villars, the Governor of Rouen, who had successfully resisted the King

in arms, now consented to treat, and agreed on March 27 to hand over Rouen,

Havre, Harfleur, and the other places under his

control. The entire province shortly passed into the King's hands; and the

dissentient Parlement of Caen united with that of

Rouen. In Picardy Abbeville and Montreuil made their submission. Many smaller

places in the centre and south-west came over before the end of May. But

military successes were needed to expedite the process of reduction. The King

moved against Laon, and, after a siege, forced it to

capitulate on July 22. This important evidence of material strength hastened

events. Amiens, Dourlens, Beauvais, Noyon, were surrendered to persuasion or force, and thus

the reconquest of Picardy was nearly completed, and the northeastern frontier

of France was protected; though in compensation the King of Spain succeeded in

attracting the League captains, de Rosne and the Duke

of Aumale, to his service, and in placing a strong

Spanish garrison in La Fere. Poitiers, and almost all

the principal places which remained to the League in Poitou, Anjou, and Maine,

were recovered. Most significant of all, the family of Guise began to treat. Elbeuf asked and received the government of Poitiers, which

he had previously held for the League. The young Duke of Guise surrendered

Champagne, and accepted in its place the government of Provence, which it was

understood he would have to recover by arms from Épernon.

The Duke of Lorraine himself made a treaty with Henry and left the coalition.

Even in Mayenne's particular stronghold of Burgundy a

movement for peace and submission began, and several towns made separate terms

with the King. Only in Britanny the Duke of Mercoeur still held up the banner of rebellion, assisted by

Spanish reinforcements, but opposed with some success by the royal forces and

an English auxiliary contingent.

The Sword of Henry IV, by Ingres

|

|

The Croquants. The Jesuits. [1594

But the break-down of authority in France had left the peasants without

protection. The troops of both parties, ill-paid and ill-disciplined, had lived

upon the country; and the local lords, to meet their expenses in the war, had

often resorted to illegal exactions. Many castles were little better than caves

of brigands. The peasants were frequently subjected to double taxation, on

behalf of the King and on behalf of the League. These manifold misfortunes had

led to local insurrections of the countryfolk in many

places, both before and after the accession of Henry; and now in 1594

throughout the districts of Limousin, Périgord, Saintonge, Quercy, and Agénois, the armed

rising of the peasants reached a dangerous height, and threatened to spread

into the neighboring provinces. It is said that

50,000 men were under arms. Henry endeavored to

pacify the rebels, known as Croquants, by offering

conciliatory terms and promising to redress their grievances; but force and

skill were necessary in addition, and the insurrection was not finally put down

until 1595. The revolt was the more dangerous, because in the south-west it

appears to have received some secret encouragement from certain dissatisfied

Calvinist leaders.

Towards the end of 1594 an enthusiast, Jean Chastel, a pupil of the Jesuits, made an attempt upon the

King's life, and succeeded in wounding him, though not dangerously. This

incident brought to a head an agitation which had long been growing against the

Jesuit Order. It was the popular belief that the Jesuits taught the lawfulness

of tyrannicide to the pupils in their schools and

colleges; the University was jealous of their influence; it was asserted that

the Society took its instructions from the King of Spain; the parish clergy

added their complaints; and already in April, 1594, a movement had been set on

foot for their expulsion. The attempt on the King's life renewed the attack;

enquiries and searches were made, and evidence was found tending to incriminate

to some extent three Jesuit fathers. The Parlement of

Paris took up the matter, and passed a decision to exclude the Order from their

jurisdiction. The Parlements of Rouen and Dijon

followed the lead; but in the jurisdictions of Toulouse and Bordeaux no action

was taken. These events tended to some extent to damage Henry in the eyes of

the Catholics and of the Pope, and to delay the date of Henry's final absolution.

While on the one hand the King found it impossible to maintain friendly

relations with every section of the Catholic clergy, on the other hand it was

equally difficult to satisfy his Calvinist friends. The declaration of

Saint-Cloud had promised to reserve to Catholics for a period of six months all

offices which might become vacant, and to confer upon Catholics exclusively the

government of all towns that might be recovered from the League. Policy

required that until his position was secure Henry should show, if anything, a

preference for the Catholics. The Catholics were the prodigal son, the

Protestants learnt the feelings of the elder brother. Devoted servants, such as Rosny and La Force, saw their claims to recognition

indefinitely postponed. The declaration of Saint-Cloud promised to the

Calvinists private liberty of conscience, the public exercise of their worship

in the places which they actually held, in one town of each bailliage and sénéchaussée, in the army, and wherever the King

might be. In 1591, in response to pressure from the Calvinists, and after

consulting with the Catholic prelates, Henry formally revoked the Edict of

July, 1588, and restored the Edict of Poitiers (1577) with its explanatory

agreements of Nérac and Fleix.

But in the compacts made with Paris, Lyons, Rouen, and other important Catholic

towns, he was forced to concede the exclusion of Calvinist worship from the

urban precincts. The more moderate of the Protestant leaders understood that

these terms were the best they could expect for the present; but extremists,

like La Trémouille, and Turenne, who in 1591 obtained

by marriage the dukedom of Bouillon, did not conceal their dissatisfaction.

Short of open hostility, they made their opposition and discontent felt in

every opportunity; and it was only by the most constant exercise of vigilance

and conciliation that an open rupture with the Protestants was avoided.

Payments to the leaders.

|

Amid

all these difficulties Henry steered his course with unfailing accuracy of

judgment, undaunted courage, inexhaustible geniality and buoyancy of spirits.

By the end of 1594 he had recovered the greater part of his kingdom. The means

adopted show his practical sagacity and disregard of conventional reasoning. He

did not hesitate to pay the price which his opponents asked; and the price

demanded was proportionate to his needs. Paris was bought comparatively cheap

for 1,695,400 livres. Rouen, and the other places

which Villars surrendered, cost 3,477,800 livres;

the Duke of Guise received 8,888,830 for himself and his immediate subordinates; the Duke of Lorraine a similar sum. La Chastre had

898,900 livres, Villeroy 476,594. These figures do not include the value of the offices and dignities

which were conferred upon the principal persons, for which indeed for the most part

they rendered an equivalent in honorable service.

When Rosny hesitated to accept Villars' terms, the

King told him not to look too closely at the figures. We shall pay these men,

he said, with the revenues which they bring to us; and to recover the places by

force would cost us more in money alone, to say nothing of time and men. The

sums asked may appear exorbitant; but it must be pointed out that all the

leaders had drawn heavily upon their private fortunes, and had incurred

enormous debts to defray their expenses in the field. With practical common

sense the King stood neither upon honor nor upon

precedent. He paid what was asked, often with a jest, and got full value for

his money. First and last, he disbursed to the leaders of the League more than

thirty-two millions of livres, far more, that is,

than a year's revenue of France at this time. But by so doing he antedated

perhaps by many years the time when he should enter into the full receipt of

his income; and in addition he saved his subjects from all the waste of war,

and secured further the profits of peace. That rebellion should be recompensed

seemed to many a dangerous example. But the King saw that the needs and the

circumstances were exceptional; and he did not intend that they should recur.

Not less extensive were the concessions which Henry was forced to allow

to the towns. Meaux was exempted from taille for nine years. Orleans was to have no royal

garrison or castle; Rouen no garrison, impost, or taille for six years; to Troyes arrears of taxation for three years were remitted; Sens, Amiens, and Lyons, were to receive no garrison. But

one danger the King avoided. He created no great hereditary governments. Such

conditions were pressed upon him with dangerous pertinacity in 1592, when fortune

had long been adverse. They were urged not only from the Catholic but also from

the Protestant side. He rejected them consistently, and thus saved the unity of

France and excluded the restoration of feudalism. Of money he was lavish,

though he can hardly have known whence he was to procure it. But every form of

permanent heritable authority he disallowed.

By one means and another, at the end of 1594, Henry might consider that

he had established his position as King of France. He proceeded to emphasise this fact in the eyes of Europe by declaring war

upon the King of Spain. Ever since his accession he had in fact been at war

with Philip. But he had hitherto been fighting rather as a party-chief than as

King. He now showed that as King he was not afraid to enter the lists with the

most powerful of European monarchs. Nor was he without allies. The United

Provinces, though unable to spare from their own needs any considerable

assistance, by their own war continued to lighten the pressure upon France. Elizabeth,

with whom he had informally concluded in 1593 an alliance of offence and

defence, occasionally furnished small sums of money, or a few thousand troops.

The Princes of Germany advanced loans, and allowed recruiting; and their

assistance was not without importance. The Grand Duke of Tuscany also granted

loans. It was hoped that the Swiss would join in the conquest of Franche-Comté,

in consideration of a share in the territory acquired. This province had

hitherto been guaranteed from attack by Swiss protection.

War declared against Spain. [1594-5

The King of France, then, determined to take the offensive. His plans

were laid for a simultaneous invasion of Artois, Luxemburg, and Franche-Comté,

while Montmorency, recently elevated to the dignity of Constable, was to defend

the frontiers of Dauphiné and the Lyonnais. A fifth

army was to attack Mayenne at his Burgundian base.

The opening of the campaign found Spain unprepared. Raids were made on Artois,

Luxemburg, Franche-Comté. But before long the invaders were rolled back.

Elizabeth withdrew her troops from Britanny; and

provision had to be made for the defence of this province against Mercoeur and the Spaniards. A force of Dutch auxiliaries

which had been serving in Luxemburg was recalled. The Duke of Nemours was

threatening Lyons; and Montmorency called for additional aid. But Henry

decided to make his first effort in Burgundy.

The Estates of this province had already urged upon Mayenne their desire for peace; and successes in this quarter might mean the recovery of

the district. By the early days of June, 1595, Beaune,

Dijon, Autun, and other places had revolted and

opened their doors to Biron (son of the old Marshal).

Velasco, the Constable of Castile, who had been busy expelling the Lorrainers from Franche-Comté, united his forces with Mayenne and advanced into the duchy of Burgundy. After

disposing of such forces as he could command for the defence of his other

frontiers, Henry hurried eastward, and arrived at Dijon on June 4, 1595. He at

once sent out reconnaissances to ascertain the

position and forces of the advancing enemy, and moved forward himself with a

portion of his cavalry to Fontaine Française. In

consequence of inaccurate and insufficient information Biron was entangled in an encounter with a superior force of hostile cavalry. The

King hurried to his aid, and found himself engaged with the vanguard of the

main opposing force, while the remainder was close at hand. A dashing cavalry

skirmish followed, in which the King displayed all the best qualities of a

soldier, and, aided by the excessive caution of the Constable of Castile,

succeeded in retrieving the error. The engagement, such as it was, was not in

any way decisive; but in its results it was equivalent to a victory. The

Constable, whose instructions were only to secure the Franche-Comté, declined

to advance further, and retired to his own province. The reduction of such

citadels as still held out against the King soon followed; and the whole of

Burgundy, except Châlon and Seurre,

came into the King's hands before the end of June. The Parlement of Dijon was reunited and reestablished. Henry even advanced into

Franche-Comté, but retired at the request of the Swiss, who disclaimed any

desire for the conquest of the country. Mayenne, who

considered himself absolved from any further obligation to his allies, now

concluded a truce with the King, and retired to Châlon,

to await the final reconciliation of the Pope with the King, which appeared to

be at hand.

In allowing a reasonable time to elapse before Henry's conversion was

accepted as genuine, Clement was acting in conformity with the circumstances of

the case. Political exigencies may have not only suggested the delay but

prescribed the moment for removing the bar. All the influence of Spain was

exercised in opposition to Henry; and Spanish ambassadors allowed themselves a

singular freedom of language in dealing with independent Popes. So long as

Henry's fortunes were uncertain the threats of Spain required consideration. In

the autumn of 1595 Henry appeared to have gained the upper hand of his enemies

in France, and to be holding his own in opposition to Spain. He was on friendly

terms with the Grand Duke of Tuscany; and the Venetians from the first had

shown him conspicuous favor. These facts may, indeed they must, have suggested

to Clement that the period of penance and probation had been sufficiently

prolonged; and the southward advance of Henry with his successful army was

another element affecting the calculation. After the most serious deliberation

in private and among the assembled Cardinals terms were concluded with the King; and on September 17, 1595, the solemn decree of absolution was pronounced.

The conditions were not unduly severe. Besides the indispensable obligation to

restore the Catholic religion and grant free exercise for its worship in all

parts of his kingdom, even in Béarn, the only points that require notice are the

provisions: that the Prince of Condé, the heir-apparent, should be brought up

in the Catholic religion; that the decrees of the Council of Trent should be

published and observed in France, with the exception of those articles which

might endanger the order and peace of the realm (a proviso which in effect

nullified the concession); and that a monastery should be built in every province

of France, including Béarn. Nothing was said about the suppression of heresy;

and, although a preference was to be given to Catholics in appointments to

offices, that preference did not imply the exclusion of Protestants.

While this

important negotiation was drawing to its close, the King was moving south to

Lyons, where the Duke of Nemours had recently died. He made his solemn entry

into the city on September 4, and the places occupied by the late Duke were

rapidly reduced. The new Duke began to treat, and his submission was solemnly

ratified early in the new year. The Duke of Joyeuse,

who had hitherto maintained his power in western Languedoc in the interests of

the League, had been weakened by many defections, and notably by the secession

of the majority of the Parlement of Toulouse. While

he was attempting to coerce the Parlement, Narbonne

and Carcassonne revolted; the bases of his strength were crumbling under him;

and he also made his peace before the end of the year. Preliminary terms were

accepted by Mayenne on September 23; the government

of the île de France was conceded to his son; three

strong places, Soissons, Châlon, and Seurre, were allotted to him for his security; and he was

allowed to treat in the quality of chief of his party. His monetary

compensation exceeded three and a half million livres.

But the price was not excessive; for Mayenne abode

loyally by his compact, and proved a faithful and valuable servant to his King.

The decrees of Folembray (January 31, 1596),

which covered the cases of Mayenne, Nemours, and Joyeuse, marked a further stage in the general restoration.

Shortly afterwards (February 17) the young Duke of Guise entered Marseilles, by

agreement with some of the principal inhabitants, just in time to defeat a plan

of Philip to seize this important harbor. The

galleys of Doria were already in the port. Since the

previous November Guise had taken seriously in hand the reconquest of his

province; and, in spite of an alliance which he concluded with Spain, Épernon had seen the area of his authority steadily

diminishing. On March 24 he made his agreement with the King; and the

reduction of the south-east was completed. Other and less conspicuous

surrenders had meanwhile taken place elsewhere; and even the Duke of Mercoeur in Britanny had

concluded a truce.

1595] Losses on the northern frontier.

But these important advantages were not to be attained without a

considerable display of military force, which was sorely needed elsewhere; and

the time spent by Henry in Burgundy and at Lyons, although most profitably

employed, coincided with a critical period of the northern campaign. The

Spanish army, commanded by Fuentes, after failing to seize the castle of Ham,

which had been held by the Duke of Aumale for the

League but now fell into the hands of the King's troops, proceeded to besiege Dourlens. The command of the French forces was divided

between Bouillon, Saint-Paul, and Villars, with the results that might have

been expected. The plan adopted for the relief of Dourlens led to a general engagement; and Villars, in covering the retreat, was

defeated, captured, and put to death (July 2e). The losses of the French were

estimated at 3000. But Nevers had meanwhile come up

with the troops under his command, and the towns on the Somme were put in a

state of defence. Fuentes turned aside and laid siege to Cambray (August 11, 1595). At this moment Henry had to choose between his expedition to

Lyons and a northward march to take command in Picardy. Results seem to prove

that his decision was wise. But a heavy price was paid for the pacification of

the south-east; and the funds disbursed by agreement to the Leaguers reduced

the royal treasury to complete destitution.

|

The position of Cambray was peculiar. The Duke

of Anjou had seized this independent bishopric on his way to the Low Countries

in the year 1581; and in the opening year of Henry's reign it was held by the Sieur de Balagny for the League. Balagny, first among the leaders of the League, had made

his terms with the King of France. The Governor of Cambray now acknowledged the royal authority; the city was held in the King's name,

and had been prepared for defence with royal assistance and by royal advice.

The force, which now beleaguered the city, was contributed and equipped by the

Spanish Netherlands, whose territory was flanked and threatened by this hostile

fortress. De Vic was sent by Henry to take charge of the defence. After vainly endeavoring to collect an army for its relief he threw

himself into the town with a small force (September 2). His arrival imparted

fresh vigor to the garrison, and gave Henry time to

complete his work at Lyons, and to issue orders for the assembling of a

relieving army. But, while the King was still on his way, having left Lyons on

September 25, the inhabitants of Cambray, with whom Balagny had always been unpopular, taking offence at the

issue of a copper token currency to defray the expenses of the garrison, rose

against their governor, seized a gate, and on October 2 delivered the city to

the Spaniards. The citadel remained; but for want of provisions that also was

surrendered on October 9. Spanish rule was established, and the authority of

the Archbishop reduced to insignificance.

To compensate for these losses the King now undertook the siege of the

Spanish stronghold of La Fère. His mission to

Elizabeth requesting assistance failed, because he was not willing to purchase

her aid by the surrender of Calais. But, by threatening to conclude a truce

with Spain, he persuaded the Dutch to send a small auxiliary force of 2000 men.

With such troops as he could spare from the defence of his own fortresses, and

with the ban and arrière ban which assembled in

response to his appeal, he sat down before La Fère (November, 1595). The state of the finances, and in consequence the provision

for the army, were deplorable. The King had to intervene almost weekly to

obtain such small sums as could suffice to keep his army together.

Meanwhile

the Archduke Albert assumed the government of the Low Countries; and, although

he was unable to relieve La Fère, by the advice of de Rosne he planned a sudden attack upon Calais,

surprised the positions which commanded the approaches to the walls, and took

the city before Henry could come to the rescue (17 April). The fall of Calais

was soon followed by that of Ham, Guisnes, and Ardres. The Protestants, discontented with the delay

interposed by some of the Parlements in the

registration of the new decrees, chose this time to press their demands upon

the King. La Trémouille and Bouillon had left the

camp at La Fère; civil war was again in sight; but

the mediation of Duplessis Mornay averted the danger. Still the King held on; and on May 16 La Fère capitulated. But as soon as the siege was completed

the army broke up. For want of funds it was impossible to keep the professional

soldiers together; and the nobles felt that they had done their duty. With

difficulty the King retained sufficient men to secure his frontier towns.

Fortunately the Archduke found work to distract his attention and to divert his

resources on the side of the United Provinces.

At this moment there was danger

that the King might be left to carry on his work alone. The Dutch were inclined

for peace, if peace could be obtained; and their foreign policy was dictated

by Elizabeth. To Henry's urgent demands for assistance during the siege of La Fère, and while the fate of Calais hung in the balance,

Elizabeth had returned no response. Until the fall of Calais she had hoped to

obtain this place as an equivalent for her aid. After its fall she still hoped

to obtain it from the King of Spain by exchange for Flushing and Brill, which

she held as security for her loans to the Dutch. Boulogne was now to be the

price of her assistance; and Henry could hardly afford to pay this price. But

a fresh embassy, despatched in April, aided by

reports of fresh designs on the part of Philip upon England, obtained more favorable terms. On May 26, 1596, an offensive and

defensive league was concluded between England and France; and the adhesion of

the United Provinces, though not immediately notified, was in principle

settled. In order to secure this support, Henry was obliged to tie his hands

and to promise that he would not make peace without the consent of his allies.

But the proposition as to Boulogne was dropped, and the designs upon Calais

came to nothing; the Dutch had been warned, and kept an eye on Flushing and

Brill. On the other hand, the great joint expedition to Cadiz, which followed

at once upon the new alliance, was mismanaged and effected little of moment.

1596-7] The Assembly of Notables.

The autumn of 1596 saw no important operations on the northern frontiers. A

French attempt to surprise Arras failed, and raids into Artois did not affect

the main issue. On the other hand this autumn saw the beginning of financial

reform, and of Rosny's activity in the Council of

Finance; and the necessary foundations for the campaign of the following year

were laid. The assembly of Notables, which Henry summoned for October, 1596,

was intended to suggest and authorise new taxation,

and to assist in the reorganization. Its members were

drawn from the clergy, the nobility, the sovereign Courts, the municipal

magistrates, and the financial officers of the Crown. Their deliberations threw

light upon the financial position, but their suggestions did little to improve

it. They discovered that the royal revenues amounted to 23 millions of livres, of which sixteen millions were appropriated to

first charges, leaving only seven millions for war, the royal household,

fortifications, roads, and public works. They agreed that the revenue ought to

be raised to thirty millions, and for this purpose they proposed the pancarte or sou pour livre: a tax of five per cent, on all goods introduced for

sale into towns and fairs, excepting corn. They reckoned that this tax would

bring in five millions, while minor reforms would supply the other two. In

operation this tax produced little more than a million and proved highly

unpopular. The picturesque story told by Sully of the establishment of a

Council of Reason, and of his own wise advice, whereby the Council was utilised and circumvented and eventually suppressed,

appears to be without historical foundation, an invention intended to exalt the

author's own importance.

Efforts to recover Amiens. [1597

|

In the early months of 1597, while Henry's ambassadors, Bongars and Ancel, were urging in

vain the Princes of Germany to combine in a final and joint attack upon the

King of Spain, Clement was working for peace. But Henry, anxious as he was to

secure for his exhausted kingdom an interval of repose and recuperation, could

not consent to any peace or truce which involved the retention by the Spaniards

of the captured places on his northern frontier. To this list Amiens was added

on March 11, 1597. When this town made its terms with the King, it was

stipulated that no royal garrison should be quartered in its precincts.

Nevertheless, relying on the strength of the fortifications, and on the loyalty

of the inhabitants, the King had selected Amiens as the depôt for the war

material collected in view of the coming campaign. The commander of Dourlens, learning of this great accumulation of valuable

stores, and also that the civic guard, although duly watchful during the hours

of night, relaxed its vigilance by day, planned an attack for the early hours

of morning, and effected his entry into the town. Resistance was overpowered;

the town was sacked; the military chest, artillery, and provisions, fell into

the hands of the Spaniards.

The King determined that his first object must be

the recovery of Amiens. Expedients were immediately devised for the collection

of funds: a forced loan, a sale of new offices, an increase in the gabelle of salt. Lesdiguières was despatched to take charge of Dauphiné.

Aid was sent to the King's lieutenants in Britanny.

The garrisons of Picardy were strengthened, and a small force was at once

collected to begin the blockade. Measures were taken for the manufacture of a

new siege-train, and the necessary ammunition. The Constable was left in Paris

to see to the execution of these orders; on March 12 the King left the capital.

Marshal de Biron had already been despatched to make preparations for the blockade.

The King began by visiting his garrisons, where he found the troops

ready to disband for lack of pay. Promises, and urgent messages for the supply

of funds, enabled him to meet this danger, and to put the fortresses in a state

of defence. Before the month of March was out Biron was established at Longpré beyond the Somme to close

the approaches from Flanders. Corbie and Pecquigny were strongly occupied. To divert attention

attacks were made upon Arras and Dourlens, of which

much cannot have been expected. On April 5 the King himself designed and

ordered the siege works necessary to cut off all access from the north. He then

returned to Paris to induce the Parlement to register

the Edicts framed in view of the extraordinary financial exigencies. "I

come to demand alms", he said, "for those whom I have left on the

frontier of Picardy". But a lit de justice was

needed, and was held on May 21. With the Parlement of

Rouen he had similar difficulties. To them he wrote, "I think rather of

the danger of an invasion, than of the formalities of laws and ordinances.

There is nothing irremediable except the loss of the State". The Parlement held out for two months, and then registered the

Edicts. The emergency was indeed dangerous; the King's prestige was shaken;

seditious attempts were made to seize Poitiers, Rouen, Rheims, Saint-Quentin;

and Archduke Albert had hopes of securing Metz. The Vicomte de Tavannes was arrested; and exceptional measures

had to be taken to restrain the Comte d'Auvergne from

open rebellion.

Meanwhile, in spite of the bankruptcy which had been forced upon Philip

in the autumn of 1596, the Archduke Albert was collecting an army of 28,000 men

to relieve Amiens. Elizabeth was entreated to make a diversion by attacking

Calais; but she confined her aid to 2000 men for six months. The Dutch sent

their stipulated contingent of 4000 men, but refused to initiate offensive

operations on their own part. But to propositions of peace from Spain the King

replied, "I will speak of it further when I have recovered Amiens,

Calais, and Ardres". Infantry was raised in the

various provinces; the nobility were called up, and promised to remain in arms

until Amiens had fallen. Rosny, who was now supreme

in the Financial Council, was stimulated to the utmost exertions, and supported

in every step which he thought necessary. The pay and provisions for the siege

of Amiens were regularly supplied up to the end, and almost from the first.

On

June 7 Henry reappeared in the camp of Amiens. The army of investment was not

yet much larger than 6000 foot, with a small force of cavalry. Nevertheless Biron had done wonders. The work of circumvallation to the north was nearly completed. The forces

were soon raised to 12,000 foot and 3000 horse; and before the siege was ended

there were 30,000 men about the town. The line of the Somme was now

strengthened at every possible point of crossing to prevent relief from

reaching the city by a circuit from the south. On July 17 a dangerous sortie

was made, but was eventually beaten back. Forty-five cannon were now battering

the walls. Saint-Luc showed conspicuous ability in the command of the artillery; and his death on September 5 was a great loss. Early in September the

Archduke Albert left Douay with a relieving army of 18,000 men, and 3000 horse,

7000 being left to guard his communications. The proposal to cross the Somme

below Corbie was thought too dangerous; and a more

direct advance upon the besiegers was substituted. On the 15th the Spanish army

appeared upon the banks of the Somme, about six miles below Amiens. The enemy,

while detaching a small force to attempt the passage of the Somme, advanced to Longpré, which had been fortified by the advice of the Duke

of Mayenne. On the approach of the main army he sent

forward trustworthy supports to strengthen this position; an attack upon it

was repulsed; and the attempt to cross the Somme was frustrated by Henry's

dispositions, the troops which reached the southern bank being driven back with

serious losses. On the 16th the Archduke retired in good order, Henry having

decided not to risk a general engagement. On September 25 Amiens capitulated.

After this the town was held by a royal garrison.

|

Peace of Vervins. [1597-8

This success opened to Henry the prospect of an honorable peace. Philip II knew that his days were numbered; he was anxious to leave to

his son a peaceful succession; he desired to make provision for his daughter,

the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia; it was clear that

nothing worth the sacrifices involved could be gained by prolonging the war

with France; and he still cherished hopes of recovering the United Provinces.

His ally, the Duke of Savoy, had been hard pressed in the south. Lesdiguières had invaded his territory, and occupied the

whole territory of the Maurienne. The forces of Savoy

had been defeated in several engagements. Prince Maurice had taken advantage of

the expedition of Archduke Albert to carry his arms far and wide into Gelders, Overyssel, Frisia, and even into Westphalia, and the Electorate of

Cologne. The expedition which left Ferrol in October for Britanny and Cornwall was scattered by storms. In October Philip opened negotiations

with France, in November he pushed them with more sincerity. Henry began to

hope.

His chief difficulty was with his allies. So recently as 1596 he had

concluded an offensive and defensive alliance with England and the Dutch, and

had promised not to make peace without their consent. In order to give some color to his defection, he pressed upon the Estates

General in November the necessity of more ample and vigorous assistance in a

joint and general war for the conquest of the Spanish Netherlands. To Elizabeth

de Maisse was sent to make similar representations.

But it would have been difficult to satisfy Henry. He was bent upon peace on

the condition of recovering his lost towns. These diplomatic demonstrations

were only intended to prepare his allies, and to give some excuse for his

desertion of them. The state of his kingdom required peace; and herein lay his

real justification. The cool reception given by Elizabeth to his proposals was

natural enough in the circumstances, and could not be considered to relieve him

of his obligations.

On January 12 Henry authorized his

representatives to negotiate with the Archduke at Vervins for a peace. The chief difficulty was the condition on which the King thought

it necessary to insist: that England and the United Provinces should be

admitted to the peace if they desired. When this had been surmounted, the Peace

of Vervins was concluded (May 2, 1598). The Treaty of

Cateau-Cambrésis was put in force again. Henry recovered all his conquered

places in Picardy, as well as the fort of Blavet in Britanny. The Duke of Savoy was included in the treaty;

and the question of Saluzzo, which he had seized from

France towards the end of the reign of Henry III, was to be decided by papal

arbitration. The Swiss were comprised in the agreement, with their allies, a

term which by implication covered Geneva. Neither Elizabeth nor the United

Provinces elected to join in the treaty; but Henry continued his unofficial

assistance to the Dutch, first by repaying gradually the sums which they had

advanced to him, and afterwards by subsidies, which ultimately amounted to two

million livres a year. About the same time the Grand

Duke of Tuscany was persuaded to give up the Château d'If and other places commanding Marseilles, which he held as security for his loan

of 3,600,000 livres.

Meanwhile the King had completed his preparations for the armed

reduction of Britanny. His intervention on this side

of France was the more necessary since Protestants, headed by the Duke of

Bouillon and La Trémouille, and leagued with the Duke

of Montpensier, and the Comte de Soissons, had long

been threatening trouble in Poitou, Limousin, Berry,

Auvergne, and neighboring provinces. The disturbed

condition of these provinces, where League captains still retained some centres for their depredations, was the excuse; but

ambition working on religious disaffection for political ends inspired the

movement.

1599] The Edict of Nantes.

In February, 1598, the King set out from Paris. On his way he passed

through Anjou and Touraine and used the opportunity to extinguish remaining

sparks of disorder due to the League, and to overawe the leaders of Protestant

disaffection. For ten years the province of Britanny had been the arena not only of faction and party strife, but also of foreign

armies, English and Spanish. Now that the King had been converted and received

by the Pope, the peace party was strong among the Bretons, as was proved by

spontaneous demonstrations in Dinan, St Malo, and Morlaix. But Mercoeur still held the strong city of Nantes, inaccessible

at certain seasons; and his strength was not contemptible. Besides 5000

Spaniards at Blavet, he had 2000 men under his own

command. Twelve places acknowledged him in Britanny and Poitou, each of which was said to be strong enough to stand a siege. The

reasons therefore, which induced Henry to compromise with Villars, Mayenne, Épernon, and others,

existed here in greater force; and Mercoeur made a

very profitable bargain. The Duke and his followers received a complete amnesty

and more than four million livres in return for the

surrender of the province, the cities, and the castles; and it was agreed that Mercoeur's daughter should be married to the natural

son of Henry and Gabrielle d'Estrées, César,

afterwards Duke of Vendôme. On the conclusion of this

treaty at Ponts de Cé (March 20) the submission of the whole north-western district, and the

extirpation of the last centres of disorder, speedily

followed; and the evacuation of Blavet by the

Spaniards after the Treaty of Vervins completed the

reunion of France under one King.

Henry moved on to Nantes, and held an assembly of the Estates of the

province of Britanny. All the irregular imposts of

the unquiet time were abolished, and arrears of taxes remitted. In return for

these benefits the Estates granted a special vote of 800,000 livres for the coming year. At Nantes the moment seemed to

have come to settle the status of the Protestants on a more satisfactory if not

on a permanent basis. The famous Edict signed in April, 1598, consolidated the

privileges which the Calvinists already possessed by the various declarations

and edicts previously passed: the Declaration of Saint-Cloud (1589), the Edict

of Mantes (1591), the Articles of Mantes (1593), and the Edict of St Germain (1594).

Although the registration of the Edict of Mantes and of the Edict of St Germain had been delayed, it had been finally accorded.

Complete liberty of conscience and of secret worship, local rights of public

worship in 200 Protestant towns and some 3000 castles of Protestant seigneurs hauts justiciers, and in one city

of each bailliage and sénéchaussée of the kingdom, free access to all public offices, these rights the Calvinists

already possessed, except in Provence and in the bailliages of Rouen, Amiens, and Paris. At the assembly of Sainte-Foy (1594) they had

claimed far more. They had planned the division of the kingdom into ten

circles, each with its separate council authorized to

collect taxes, to maintain troops, to accumulate war material. A central

assembly of deputies, one from each of the ten circles, was to combine and harmonize the common policy. There was also talk of a

foreign protector to preside over this internal and independent State. The

object of the Edict, which bears the stamp of a temporary measure, was to

extend religious liberty so far as was consistent with the temper of the time

and with special conditions made with rebellious towns and districts, and to

limit political independence so far as was compatible with the not unnatural

fears and suspicions of the Protestants, who still remembered the day of St

Bartholomew and the ascendancy of the Guises. Liberty of public worship was

extended to two places in every bailliage or sénéchaussée; a limited number of seigneurs not hauts justiciers were allowed to

establish public worship in their castles; and in all places where it already

existed it was authorized. The King assigned a sum of

money for Protestant schools and colleges, and authorized gifts and bequests for this purpose. Full civil rights and full civil

protection were granted to all Protestants, and special Chambers (Chambres de l'Édit) were

established in the Parlements to try cases in which

Protestants were interested. In Paris this Chamber was composed of specially

selected Catholics with one Protestant Councillor;

in Bordeaux, Toulouse, Grenoble, one half of the members were to be Protestant.

The admissibility of Protestants to all public offices was confirmed and even

the Parlement of Paris admitted six Protestant councilors.

The political privileges granted were of a liberal, even of a dangerous

character. The Calvinists were allowed to hold both religious synods and

political assemblies on obtaining royal permission; this condition was at

first omitted in the case of the synods, but was later seen to be necessary.

They retained the complete control of the 200 cities which they still held,

including such powerful strongholds as La Rochelle, Montpellier, and Montauban. The King agreed to supply funds for the maintenance

of the garrisons and the fortifications, hoping, it may be, in this manner to

retain a hold upon them. The possession of these cities and towns was at first

only guaranteed until 1607, but it was prolonged until 1612. If, as may be

surmised, Henry looked forward to a time when this provisional guarantee should

no longer be thought requisite, that hope, like many others, remained

unfulfilled at his death. After considerable opposition on the part of the Parlements the Edict was finally registered in 1599, at

Paris; and the other Parlements sooner or later

accepted it with some restrictions.

The Edict, according to modern ideas, grants more and less than was

desirable. Religious liberty was incomplete, while local political liberty was

excessive and dangerous. The reasons for both defects are too obvious to

require explanation; and, in spite of them all, the registration of the Edict

of Nantes in 1599 worthily marks the completion of the first part of Henry's

work in France. Union was now restored; the League was at an end; an honorable peace had been concluded with Spain; the

frontiers of France had been recovered; order was established throughout the

land, and a law securing adequate religious liberty was not only enrolled but

respected. The remaining years of Henry's reign, in spite of some trifling wars

and the menacing storm-cloud that arose before his death, were years of peace

and returning prosperity. The way was now clear for administrative reform;

but, before attempting an estimate of what was achieved in that direction, it

will perhaps be well to conclude the narrative of events which henceforth admit

of a more summary treatment.

1599-1601] War with Savoy.

The controversy with the Duke of Savoy concerning

the marquisate of Saluzzo was left by the Peace of Vervins to the arbitration of the Pope. The Treaty of

Cateau-Cambrésis assigned the disputed territory to France, so that the

arbitration seemed to be an easy matter. But the Pope soon found that the

parties were irreconcilable; and in 1599 he renounced his ungrateful task.

Direct negotiation proved equally fruitless. It was plain that the Duke of

Savoy relied upon arms to maintain his claim. Fuentes, the Spanish Governor of

Milan, encouraged him to hope for Spanish aid; and it is probable that he

relied upon the help of friends in France. Henry offered to exchange Saluzzo for Bresse and certain neighboring territories. Abundant time was given for the

consideration of this offer; but the Duke continued to temporisze; and at length in August, 1600, the King decided to resort to arms.

Rosny, who was now not

only Surintendant of Finance, but also Grand Master

of the Artillery, had raised the funds and constructed the finest siege-train

that had hitherto been seen. An army under Biron was

directed to invade Bresse, another under Lesdiguières to invade Savoy. On the same day, August 13,

the towns of Bourg in Bresse and Montmélian in Savoy were taken by assault; and Chambéry opened

its gates. In spite of understandings between Biron and the Duke of Savoy, and secret information supplied by the latter, the

campaign resembled a military promenade. Castles reputed impregnable melted

like wax under the fire of the new and powerful artillery. The King, after

seeing that all was going well in Savoy, joined the army of Bresse; and under his eye any traitorous dispositions on the part of Biron were left little chance. The fall of the citadel of Montmélian (November 16) completed the military occupation

of Savoy and Bresse, with the exception of the

citadel of Bourg. The fort of Sainte-Catherine, a constant menace to Geneva,

was destroyed. On January 17, 1601, the Duke of Savoy was obliged to come to terms,

and ceded in return for Saluzzo the lands of Bresse, Bugey, Gex, and Valromey, in lieu of an

indemnity. The King rounded off his territory in France, and seemed to

renounce the Italian ambitions of his predecessors.

During this period another urgent desire of the King had been fulfilled.

He had long been separated from his wife, Margaret Valois; and the fear that

Gabrielle d'Estrées might be her successor had alone

prevented the Queen from agreeing to a divorce. The death of Gabrielle (April

10, 1599) removed this obstacle. The papal Court proved complaisant; the Queen

agreed; and on December 17, 1599, the marriage was dissolved. A conditional

promise of marriage to another mistress, Henriette de

Balzac d'Entragues, threatened to interpose another

difficulty; but the conditions were not fulfilled; and Henry was free to

marry the princess of his choice, Maria de' Medici, who became his wife on

October 5, 1600. On September 27,1601, the Queen gave an heir to France. Other

children were afterwards born; and all fear as to the succession was now

removed.

Designs of Henry. [1598-1610

The career of Henry IV is an unfinished career. The Peace of Vervins marks the end of the first period. By 1598 internal

peace had been established; and external peace until 1610 was only disturbed

by the brief war with Savoy. The second period was a period of peace, but of

peace as a preparation for war. The third period had just begun when the

assassin's dagger cut short the execution of that policy which, after all

apocryphal details have been struck out, may still deserve to be termed his

"Great Design". The exact nature of the King's plans cannot now be

ascertained. Of the fantastic and discredited imaginations of Sully little use

can be made, and that only with the greatest caution. More may be learnt from

the confidential correspondence of the King, if care be taken to distinguish

between schemes entertained for a moment and indications of settled and

continuous policy. But the safest guide to the ultimate aims of Henry is the

study of his action as a whole from the Peace of Vervins to the outbreak of the Cleves-Jülich War. Reserve,

restraint, economy, organization, silent and

steadfast advance, the gradual addition of alliance to alliance, indicate that

the purpose was so great as to require the employment of all available

resources. The establishment of universal toleration may have been subsidiary

to the main design; but religion was consistently postponed to politics; the

real end was the political hegemony of Europe, which could only be obtained at

the expense of the House of Habsburg as a whole. For a time antagonism appears

to be mainly directed against Spain; but, as the combinations widen and

mature, the Austrian House is seen to be also included; and against Austria in

fact the first blow was actually directed.

Some years were needed for the settlement of unsolved domestic problems.

The final dissolution of the League, the peace with Spain, and the Edict of

Nantes, did not free the realm of France from elements of disquiet, disunion,

and intrigue; and the play of these forces was seldom unaffected by external

influences. The conspiracies of the years 1598-1606 are compounded from the

potent ingredients of personal ambition and religious discontent; they work

upon a society not yet weaned from traditions of faction and disorder; and

they rely upon the secret support of Spanish ambassadors and the Spanish Court.

In Biron personal ambition predominates; in Bouillon

it is strengthened by the impulses of a party chief; in the Comte d'Auvergne and his sister, Henriette d'Entragues, a personal, almost a dynastic, motive

prevails; but the several conspirators work with each other and with Spain,

though the diversity of their several ends facilitates the operations of

defence.

Charles de Gontaut, duc de Biron (1562–1602), son of Armand de Gontaut, baron de Biron, fought brilliantly for the royal party against the Catholic League in the later stages of the Wars of Religion in France. He was made admiral of France in 1592, and marshal in 1594; governor of Burgundy in 1595, he took the towns of Beaune, Autun, Auxonne and Dijon, and distinguished himself at the battle of Fontaine-Française. In 1596 he was sent to fight the Spaniards in Flanders, Picardy and Artois. After the peace of Vervins he discharged a mission at Brussels (1598). From that time he was engaged in intrigues with Spain and Savoy; notwithstanding these, he directed the expedition sent against the duke of Savoy (1599–1600). After fulfilling diplomatic missions for Henry IV in England and Switzerland (1600), he was accused and convicted of high treason and was beheaded in the Bastille on the 31st of July 1602.

|

|

The old Marshal de Biron had been one of the

first to adopt the cause of Henry after his accession. He had demanded a

substantial price for his adhesion; but, having received it, he did good work.

His conduct on one or two occasions, notably at the siege of Rouen, gave cause

for suspicion that he was prolonging the war in order to enhance the value of

his own services. Such suspicions are, however, easier to conceive than to

confirm; and he had given his life for the King. After his death his son stood

high in Henry's favor: he was a dashing soldier; and at Amiens he had shown

himself before the King's arrival a good commander. After the King joined the

besieging army, Biron's jealousy, vanity, and

uncertain temper, impaired his usefulness; he was already in communication

with the Archduke; later, it is said, he confessed that he purposely left the

important position of Longpré undefended, in order

that the Archduke might throw succor into the city,

and that the King might thus still be dependent upon himself. This omission was

retrieved by Mayenne's foresight; and the purpose of

the conspirator was defeated. The King loaded Biron with favors; he was made a Marshal, a Duke, and

Governor of Burgundy. But his ambition does not seem to have been satisfied.

During the war with Savoy he was in communication with Charles Emmanuel and

with Fuentes; and several acts of treachery are laid to his charge. The Duke

of Savoy had promised him his daughter in marriage; and this alliance,

suspicious in itself, was rendered more suspicious by concealment. In 1601 he

made a partial confession to the King, who freely pardoned him. But it seems

that he nevertheless continued his secret intrigues.

Death of Biron.—Auvergne. [1601-4

The scope of his designs was wide and vague. There can be no doubt that

he was in communication with the Duke of Savoy, with the Viceroy of Milan, and

with the King of Spain; and that he approached all who were supposed to be

malcontent (the Duke of Bouillon, the Comte d'Auvergne,

La Trémouille, the Comte de Soissons, the Duke of Montpensier, the Duke of Épernon) and endeavored to organize a

rising, which, if successful, would have led to the dismemberment of France in

the interests of private ambition, Protestant particularism,

and Catholic exclusiveness. To reconcile these diverse interests would have

been difficult, if not impossible; even at the outset this difficulty became

apparent. The King's prestige was growing day by day; and the prospects of the

conspirators seemed by no means hopeful. Bouillon and Auvergne, however, were certainly

implicated in Biron's designs. Henry was well aware

that Biron was engaged in dangerous intrigues. In

September, 1601, he sent him on a mission to Elizabeth, who gave him a very

suggestive lecture on the fate of Essex. But the lesson did not avail; and in

1602 significant preparations abroad, which could not be concealed, seemed to

indicate that the plot, whatever its nature, was nearly mature. At this stage

it was discovered that La Fin, a discarded agent of Biron,

was ready to make disclosures. La Fin was sent for; the King listened, and

took measures to defeat the plot. All the suspected personages found that the

King required their presence on important business. Some gave satisfactory

assurances; but Bouillon and La Trémouille kept

away. By an ingenious device all artillery was withdrawn from Biron's province of Burgundy, and troops were massed in

every dangerous quarter. At length Biron consented to

appear before the King at Fontainebleau, where he arrived on June 12, 1602.

The

King knew all, or nearly all; but he was still anxious to save the Marshal,

whom he seems to have dearly loved. A confession and complete submission would

have saved him, but no confession or submission was forthcoming. The Marshal

was too proud or too suspicious. He protested his complete ignorance of any

criminal intention other than those which he had previously admitted. There was

no other way. Biron and Auvergne were arrested. Biron was sent to trial before the Parlement.

The verbal pardon which he pleaded had no legal validity; it was more than

doubtful whether the pardon covered all his offences up to its date; it could

not cover subsequent proceedings. Among the documents put into court and

acknowledged by the accused was a memorial of some length and considerable

detail, supplying full information about the King's army to the Duke of Savoy.

This and other autograph documents supplied by La Fin made the case clear, even

without his verbal testimony; and justice took its course. On July 31 the

Marshal suffered the death penalty. There is much that is doubtful, much that

is unintelligible, in the case of Biron; but it can

hardly be doubted that he was guilty, and that the King did his utmost to save

him. After four months of imprisonment Auvergne made a full confession, and

received his pardon. Many details were ascertained after Biron's death.

Auvergne may have owed his safety to his half-sister, Henriette d'Entragues, Marquise

de Verneuil, the King's mistress. But the family

deserved little consideration. The promise of marriage, mentioned above, was

the excuse for their discontent. It not only gave plausible ground for a

grievance, it opened the way for vague claims to the succession on behalf of Henriette's children. In 1604 the King demanded and

obtained its restitution; a little later all the intrigues which the family

had been carrying on with Spain and with Bouillon became known, and the father,

the daughter, and Auvergne were arrested. Henriette was pardoned; Auvergne, who was indiscreet enough to quarrel with the still

powerful mistress, was, however, kept a prisoner. But this plot and the

previous attempt of the Prince of Joinville, son of the Duke of Guise, serve

mainly to show how firmly the King's power was established.

1604-6] Bouillon. The Protestants.