| |

CHAPTER 19

THE DUTCH REPUBLIC.

THE consequences of the assassination of William the Silent were not so

momentous as his enemies had expected. The task undertaken by him had been so

far accomplished, that his death in no way impaired the firm resolution of the

revolted Provinces to maintain to the end their desperate struggle against the

Spanish tyranny. On the very day of the murder (July 10, 1584), the States of

Holland, sitting at Delft, passed a resolution "to uphold the good cause

with God's help without sparing gold or blood"; and this resolution was

at once forwarded to all officers in command on land and sea. The people,

though stirred to indignation by the crime, everywhere preserved a calm and

determined attitude. There was no panic, nor was submission thought of for a

single instant.

William's death had left the government of the country in an amorphous

condition. It would indeed be more correct to say that no government existed.

When the authority of Philip II had been finally abjured, the sovereignty

reverted to the several Provinces, and by their delegation was vested in the

States General. But that body had only been anxious to find someone able and

willing, under proper guarantees, to step into the place forfeited by the

Spanish King. Failure and disappointment had attended their first efforts; and

they had only been saved from ruin by putting trust in the leadership of the

Prince of Orange, who, although he had steadily declined any offer of

sovereignty, had guided them by his courage and sagacity through the long years

of their desperate struggle. At length, in 1584, William had, though

unwillingly, accepted for himself the Countship of

Holland and Zeeland, and had secured for the Duke of Anjou, despite his

misdeeds, the lordship over the other Provinces. By their almost simultaneous

deaths the sovereignty reverted once more to the States General. It was an

extraordinary state of affairs; for, when we speak of the sovereignty being

vested in the States General, it must be remembered that the States General

themselves were possessed of no real authority. They were composed of delegates

from a number of Provincial States, each of them sovereign. These delegates

were simply the mouthpieces of the particular States which they represented,

and the opposition of a single Province was sufficient to paralyse the action of all the rest. These Provincial States again were practically

representative of the municipal corporations (vroedschappen)

of the great towns. But these vroedschappen were

close, self-coopting burgher aristocracies, with

immunities and privileges which made them almost independent; and they were

very jealous of their rights. Moreover, instead of there being anything

approaching an equality of real power among the sovereign Provinces represented

in the States General, Holland and Zeeland had not only borne the brunt of the

war, but were, especially the former, the richest, the most energetic, and the

most prosperous among them. They contributed some four-fifths of the charges

and furnished the formidable fleets which formed the chief defence of the

country. These two, while content to work together, though with many bickerings, looked upon the inland Provinces rather as

protected dependencies than as allies and equals. Gelderland, Utrecht, and

Overyssel naturally resented such an assumption; but, now that the great

Provinces of Brabant and Flanders could no longer be reckoned upon as a bulwark

on the southern frontier against the military power of Spain, they found

themselves compelled to choose between the bond uniting them to the overbearing

Hollanders or submission to Parma. For, in the course of the year that followed

William's death, resistance to the Spanish forces south of the Meuse had been

practically extinguished by the military and diplomatic skill of their great leader.

One after another all the chief towns of Brabant and Flanders, Bruges, Dendermonde, Vilvoorde, Ghent,

Brussels, and lastly Antwerp, had fallen before the victorious general of King

Philip. The seaports, Ostend and Sluys, alone

remained in the hands of the patriots.

1685-6] Negotiations with France and England.

Thus it is not to be wondered at that

the States General should have believed their only hope of safety to lie in

securing some foreign potentate as their sovereign, who would be able to lend

them armed assistance, and give unity of purpose to their councils. The only

two Powers to whom they could turn were the same with whom they had already

been in correspondence upon the subject, France and England. Elizabeth,

however, had shown so strong a disinclination to embroil herself with Philip

for the sake of the Netherlands, that, despite the deep offence which Anjou had

given, negotiations were again on foot at the time of the Duke's death for his

return to the country as sovereign with strictly limited powers. The States

General therefore determined to adhere to William of Orange's policy on this

head, and in the first instance to offer the protectorship of Holland and Zeeland and the sovereignty of the other Provinces conditionally

to Henry III of France. An embassy was despatched accordingly. But the form of the offer displeased the King; and he was

preoccupied with the serious discords in his own kingdom and the dangers which

threatened his own throne.

He refused to consider the proposal, unless the sovereignty of all the

Provinces were laid at his feet. The negotiation therefore came to nothing

(1585).

All this time an influential party in Holland, at whose head was the

Advocate Paul Buys, was in favor of an English alliance. But Elizabeth was

quite as coy as her brother of France. She received the Dutch envoys with fair

words; but, partly on principle, partly from prudence, declined the proffered

sovereignty. All she would undertake was to give a limited amount of military

aid on characteristically commercial terms. The towns of Flushing, Brill, and Rammekens were to be handed over to her, as pledges for the

repayment of her expenses. In the matter of bargaining the Dutch on this

occasion certainly met their match in Queen Elizabeth, who after the treaty was

agreed upon, August 10, 1585, still spent some months in haggling over petty

details. But the fall of Antwerp, which she had not anticipated, hastened her

decision. She agreed to despatch at once 5000 foot

and 1000 horse, together with garrisons for the cautionary towns, under the command

of her favorite, the Earl of Leicester. He landed at

Flushing on December 19, and received everywhere an enthusiastic welcome, even

the States of Holland, afterwards his foes, writing to the Queen, "that

they looked upon him as sent from Heaven for their deliverance". There was

an eager desire to confer sovereign powers on him; and he was nothing loth. Without consulting Elizabeth he allowed himself,

February 4,1586, in the presence of the States General and of Maurice of

Nassau, to be solemnly invested with almost absolute authority, under the title

of Governor-General. Practically the only restrictions placed upon him were

that the States General and Provincial States should have the right of

assembling on their own initiative; that the existing Stadholders should be irremovable; and that appointments to offices in the several

Provinces should be made from two or three names submitted to him by the

States. A new Council of State was created in which two Englishmen had seats.

But Leicester was disappointed. His correspondence clearly shows that he wanted

to be, for a time at any rate, in the position of a Roman dictator, though not

from mere vanity or for the purpose of robbing the Netherlander of their

liberty, but as a means to an end. But with good intentions he had little

sagacity or tact, and he speedily found that his ideas conflicted not merely

with those of a people obstinately attached to their time-honored rights and liberties, but with those of his royal mistress herself. Elizabeth

received the news of his inauguration to office as Governor-General with high

indignation. Leicester was ordered to resign his dignity; and Lord Heneage was despatched to Holland

to rate both him and the States General for their conduct. Not till July did

the Queen's favorite succeed in appeasing her wrath,

or obtain her consent to his being styled Governor-General, and being addressed

as "Excellency."

Leicester as Governor-General. [1584-6

The new Governor, who could speak no Dutch and knew nothing of the

people with whom he had to deal, speedily found himself in difficulties. On

April 4, 1586, he issued a placard forbidding, on pain of death, all commercial

intercourse with the enemy. The exportation of grain, provisions, or other

commodities to all countries under the sway of Philip II was henceforth

absolutely prohibited. The Spaniards were dependent upon the Dutch for the

supply of the necessaries of life; and, if only these could be effectually cut

off, the armies of Parma would be starved out. In this reasoning, however,

Leicester left out of account the vital importance of this traffic to the

merchants of Holland and Zeeland. The purse of Holland and Zeeland furnished

the sinews of war, and equipped the fleets and paid for the armies; and it was

their great carrying and distributing trade which filled the purse. The inland

districts, which were constantly exposed to the destructive ravages of the

enemy's troops within their borders, were jealous of the greater prosperity of

the maritime Provinces. Already in 1584, under pressure from their representatives,

the States General had attempted to stop the grain traffic with the enemy in

the interests of the country at large; but Amsterdam, supported by the States

of Holland, had refused to obey the edict, and had carried the day. The yet

more stringent prohibition proposed by Leicester at the instigation of the

democratic party at Utrecht, who had a special grudge against the Hollanders,

brought upon him their lasting hostility. The course rashly adopted by him was,

in fact, really impracticable.

Meanwhile, Parma continued to advance further northwards; in June

Grave, and in July Venloo, fell into his hands.

Leicester was too much engrossed with the difficulties of internal

administration to conduct the operations of war with the necessary vigor. His efforts towards curbing what he regarded as the

contumacious opposition of the Holland merchants and regents to his authority

only made the breach wider. He surrounded himself with a circle of advisers

from the southern Netherlands, the three most prominent members of the favored group being Jacques Reingoud and Gérard Prouninck surnamed Deventer, both Brabanters, and Daniel de Burchgrave, a Fleming. On June 26 Leicester surprised the

Council of State by the sudden announcement that he had created a Chamber of

Finance, to which he had handed over the control of the Treasury. One of the

special duties of this Chamber was to see that the placards against trading

with the enemy were stringently enforced; and to effect this it was proposed

to arm it with inquisitorial powers, extending even to the inspection of the

books of suspected merchants. At its head was placed the Count von Neuenaar, Stadholder of

Gelderland, Utrecht, and Overyssel, with Reingoud as

treasurer-general and de Burchgrave as auditor. Leicester's

arbitrary act deprived the Council of State of one of the most important of its

functions, while foreigners were appointed to offices of financial control.

Paul Buys, to whom the post of Commissary had been offered, refused to serve

under Reingoud, and notwithstanding his English

sympathies became one of Leicester's most pronounced opponents. Oldenbarneveldt, his successor as Advocate of Holland,

likewise exerted his great influence with the States of that Province to resist

the invasion of their rights.

The Governor on his part leant more and more on

the support of the democratic party of Utrecht, who with the help of Neuenaar had deprived the old burgher oligarchy of the

reins of power. Leicester secured the election of his confidant Deventer as

burgomaster of the town, though as a foreigner he was disqualified from holding

such an office; and the burgher captains and Calvinist preachers were his

staunch partisans and allies. It was highly impolitic for the Governor-General,

whose special task was to give unity to the national opposition to Spain, thus

to accentuate the differences which divided Province from Province. But he was

resolved to try conclusions with his adversaries; and Paul Buys was arrested

at Utrecht and imprisoned.

1586] Mistakes and difficulties of Leicester.

West Friesland had long been merged in the Province of Holland and was

known as the North Quarter. Leicester now resolved to revive the

semi-independency of former times by appointing Sonoy Stadholder of West Friesland, thus openly ignoring

the fact that that office was already held by Maurice of Nassau, who, as

Admiral-General, also had supreme control of the naval forces of Holland and

Zeeland. The Governor, however, took upon himself to erect three independent

Admiralty Colleges of Holland, Zeeland, and the North Quarter, thus, to the

great detriment of the public service, creating a system destined to last as

long as the Dutch Republic. He made himself still more unpopular by violently

espousing the cause of the extreme Calvinist preachers and zealots, and allowing

a so-called National Synod to meet at Dort (June, 1586), whose aim was the

suppression of all rites and opinions but its own, including those of the large

"Libertine" or moderate party, at the head of which stood Oldenbarneveldt, the inheritors of the principles of

William of Orange. As the year 1586 drew to its close Leicester became more and

more dissatisfied with his position. He had to draw largely on his private

resources to meet his expenses; and his forces were so weak that Parma could

have overrun Gelderland and Overyssel with ease, had his master but given him a

free hand. Philip's attention, however, was absorbed in preparations for the

invasion of England, an enterprise for which the cooperation of Parma's army by

land was essential. So soon as England had been conquered, the Netherlands

could speedily be coerced into submission.

Disgusted at the many rebuffs he had suffered, Leicester, towards the

end of November, determined to return to England and represent his difficulties

in person to the Queen. The exercise of authority during his absence was left

in the hands of the Council of State. But this body was merely the executive of

the States General, and therefore in reality depended upon the support of the

States of the sovereign Provinces. Besides, distrust was felt at the presence

in the Council of two Englishmen, and of Leicester's foreign nominees; and

this distrust was speedily intensified by the traitorous surrender to the enemy

of Deventer and Zutphen by their English Governors, Stanley

and York. The defection of these two adventurers, both of them Catholics

formerly in Spanish service, threw suspicion on all Englishmen. Neither the

death of the chivalrous Sidney on the field of Warnsfeld,

nor the proved gallantry of the Norrises, Cecils, Pelhams, and Russells were allowed to atone for these base and damning

acts of treachery, which delivered the line of the Yssel into Parma's hand. At the instigation of Oldenbarneveldt the States of Holland and Zeeland determined to act independently both of the

States General and the Council. A Provincial army was formed; a new oath to

the States was imposed on the levies; and additional powers, with the title of

"Prince", were given to Maurice, under whom the experienced Count Hohenlo was appointed Lieutenant-General. In West Friesland Sonoy was forced to acknowledge his subordination to

the Stadholder of Holland. Such was the influence of Oldenbarneveldt, that he was able to obtain for his

measures the concurrence of the States General, and of the Council, which was

purged of objectionable members. A remonstrance drawn up by him was sent in the

name of the States General to Leicester, in which the faults and mistakes of

the absent Governor were relentlessly exposed.

The terms of this document gave

great offence to Elizabeth; but it did not suit her policy to abandon the cause

of the Netherlands, and an accommodation was patched up. In July, 1587,

Leicester returned to his post, welcomed by his partisans, but coldly and

suspiciously received by the Holland leaders. His success or failure depended

now upon his attitude towards the States of Holland and the States General, in

which Holland was dominant. He came back determined to master them, but his

conduct had already raised a question, which for two centuries was to divide

the Dutch people into opposing parties: the question of the sovereignty of the

Provinces. Elaborate arguments were brought forward to show that the sovereign

power, formerly exercised by Charles V and Philip II, had by the abjuration of

his sovereignty become vested in the States of each several Province. Hence it

would follow that Leicester, as Governor, was subordinate to the States as

Margaret of Parma had been to King Philip. This assumption of the States of

Holland was historically indefensible; but Oldenbarneveldt had offered to resign his post as Advocate in April rather than yield on this

head. He thus founded a party with whom the question of Provincial sovereignty

became a principle; and the unwise attempts of a foreigner to erect a

democratic dictatorship at the expense of the burgher oligarchies intensified a particularism, which was for many years to prejudice

the national action and the best interests of the country. Leicester's motives

were probably good, and his supporters were numerous and active; but he had not

in him the makings of a statesman. One of the first effects of his continuous

struggle for supremacy with the States of Holland was the failure to relieve Sluys, which important seaport, on August 5, fell into the

hands of Parma. Had Farnese not been occupied with other projects, it is indeed

difficult to see how, in this time of division and cross-purposes amongst his

opponents, his further advance could have been arrested. Leicester would have

been powerless to offer an effective resistance. His political efforts, though

backed by such skilful and influential partisans as Deventer at Utrecht, Sonoy in the North Quarter, and Aysma in Friesland, failed against the firm resolve of the States of Holland and their

able leader. All his attempts to create a revolution by the overthrow of the

supremacy of the regents in the principal towns miscarried. Dispirited at last

by a fruitless struggle, and in broken health, he on August 6,1587, finally

turned his back definitely on the country, which had, as he thought, treated

him so badly. "Non gregem, sed ingratos irmitus desero" was the motto inscribed on a medal struck upon

the occasion. He came back a poor man.

Oldenbarneveldt and the Province of Holland, [1576-88

The position of the States at the

beginning of 1588 appeared all but desperate. Their army was weak in numbers

and in discipline, and without leaders of repute. The Provinces themselves were

split into contending parties and jealous of each other. They had no allies to

whom they could turn for help. Opposed to them stood the first general of his

time, at the head of a large and seasoned force, which he had led to repeated

triumphs. Already the whole country to the east of the Yssel and to the south of the Meuse and the Waal was practically in his hands. His

plans were laid for completing the work so well begun; and, had he been

unhampered, Parma would have in all probability in a couple of campaigns

crushed out the revolt in the northern Netherlands.

He was not, however, destined to have a free hand. King Philip had set

his heart upon the conquest of England by the Invincible Armada. In vain Parma

urged that the subjugation of the rebel States was now in the King's power, and

that it was not only wise, but necessary, to finish the one task before

embarking upon another. The Duke was ordered to collect an immense fleet of

transports at Sluys and Dunkirk, and to hold his army

in readiness for crossing the Channel, so soon as the Great Armada appeared in

the offing to act as his convoy. The story of what ensued is told elsewhere.

The weary months of waiting, and the failure of Parma to put to sea in the face

of the swarms of Dutch privateers that kept watch and ward to oppose his

egress, gave breathing time to the Provinces, and at the same time filled the

mind of the suspicious Philip with distrust of his nephew.

Moreover, the scheming brain of the Spanish King, undeterred by the

crushing disaster of his "invincible" fleet, was already busy with

projects of aggrandizement in France; so that,

instead of being able to devote his energies to the reconquest of the

Netherlands, during the remainder of his life Parma was chiefly occupied with

futile expeditions into French territory. Thus, just when it seemed that

nothing could avert the complete subjugation of the United Provinces, the

attention of their adversary was fixed on other costly enterprises; and the

resources of Spain, already gravely crippled, were drained to exhaustion.

After the departure of Leicester it seemed as if the loose federation of

the United Provinces must fall apart through its own inherent separatist

tendencies, and the utter lack of any workable machinery of government. The

executive power was nominally vested in the Council of State; but the presence

upon it of the local English commander and of two other English members

weakened its authority, and rendered it unacceptable to the Provinces,

especially to Holland, whose representation upon it in no way corresponded to

her position and influence. Gradually, therefore, the States General curtailed

its powers, and consulted it less; until a few years later it complained that

all the most important affairs of the Provinces were determined and carried out

without its cognisance. The driving-wheel of the

government was now to be found in the predominance of the Province of Holland,

as personified in the person of her Advocate, Oldenbarneveldt.

This great statesman, the real founder of the Dutch Republic, as it was known

to history, with consummate ability took advantage of the interval of

comparative repose which followed the withdrawal of the English Governor, in

order to gather into his own hands the reins of administration.

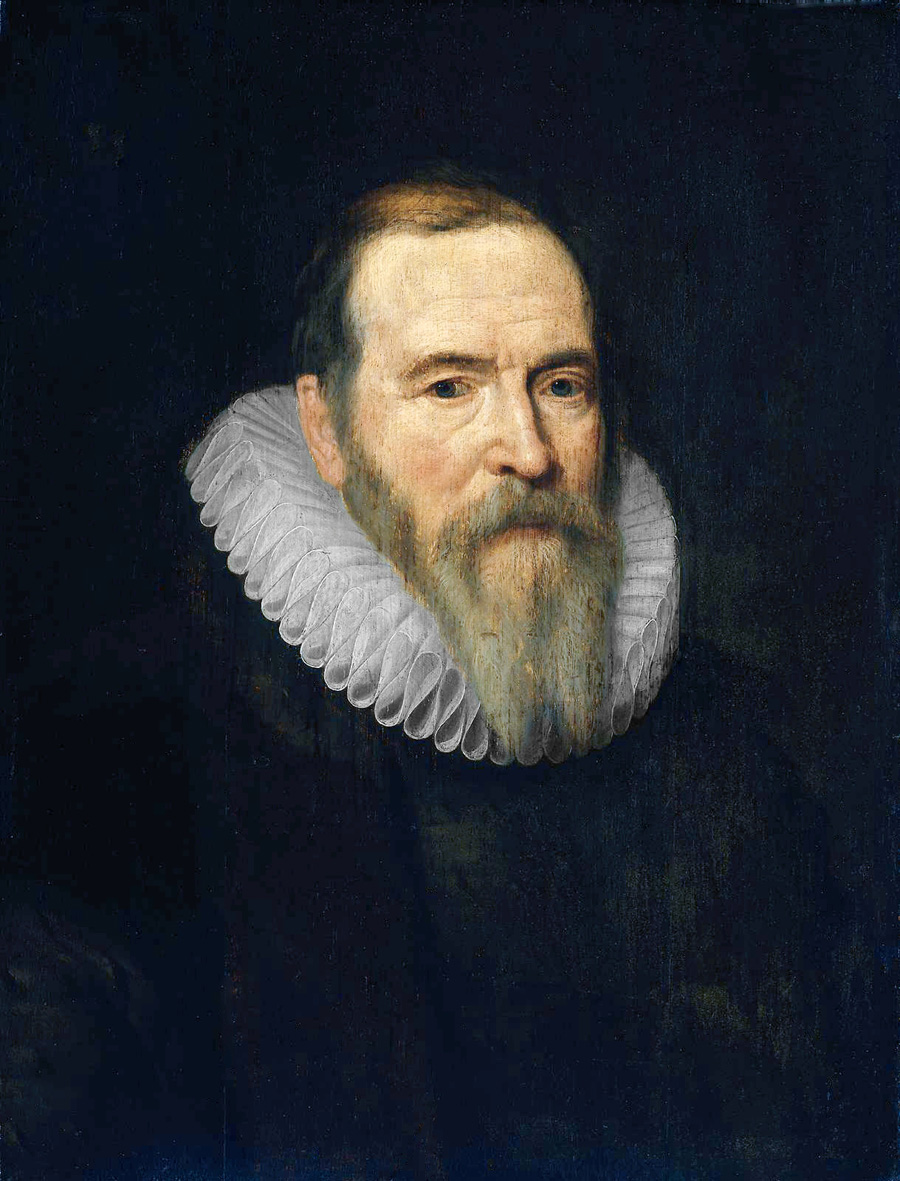

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547– 1619) |

|

Johan van Oldenbarneveldt was born at

Amersfoort in 1547. After he had begun practice as an advocate at the Hague, he

became a fiery adherent of Orange, and bore arms at the time of the sieges of

Haarlem and Leyden. In 1576 he was appointed Pensionary of Rotterdam, and thus became a member of the States of Holland. His industry

and powers of persuasion, and his practical grasp of affairs, soon won him his

prominence; and, having in 1586 been chosen Land's Advocate in succession to

Paul Buys, he filled that important post for the next thirty-two years, thus

exercising a commanding influence on the affairs of his country, and upon

general European politics. For though the Advocate was nominally only the paid

servant of the Provincial States of Holland, yet the permanency of his office,

and the multiplicity of his functions, gave to a man of great ability a

controlling voice in all discussions, and almost unlimited authority in the

details of administration. As practically "Minister of all affairs", Oldenbarneveldt became in a sense the political

personification of the Province whose servant he was, and of which he was the

mouthpiece in the Assembly of the States General. Thus it came to pass that a

many-headed system of government, whose divided sovereignty and hopelessly

complicated checks and counter-checks appeared to forbid united action or

strong counsels, acquired motive power, which enabled it to work with a certain

degree of smoothness and efficiency. The voice of Oldenbarneveldt was that of the Province of Holland; and the voice of Holland, which bore more

than half of the entire charges of the Union, was dominant in the States

General.

But the Dutch Republic, in these first years of its consolidation as a

federal State, required the services of the soldier quite as much as those of

the statesman. Fortunately in Maurice of Nassau a great commander arose, who

possessed precisely the qualifications needed. Maurice was only seventeen years

of age at the time of his father's murder, and was at once appointed in his

place Stadholder of Holland and Zeeland, and also

first Member of the Council of State. During the next few years he had busied

himself in the study of mathematics, and in acquiring both technical and

practical acquaintance with the art of war. He served in several campaigns

under Hohenlo, and from the first devoted himself

seriously to the task of gaining a thorough knowledge of military tactics. He

was a born soldier; politics had no attraction for him. In August, 1588, he was

created Captain-General and Admiral of the Union by the States General, and in

succession to Neuenaar, who died in October, 1589, he

was elected by the Provinces of Utrecht, Gelderland, and Overyssel to be their Stadholder. All the stadholderates,

with the single exception of Friesland, of which his cousin, William Lewis of

Nassau, was Stadholder, were thus united in the

person of Maurice. As in addition to this he was charged with the supreme

control in military and naval affairs, Oldenbarneveldt found ready to his hand an instrument capable of carrying out his plans, and of

translating policy into action. Many years were to pass before there arose even

the faintest suspicion of jealousy or opposition between these two men, both so

capable and ambitious. Their spheres of interest were distinct ; and the

younger man was content to leave in the hands of his father's trusted friend

the entire management of the affairs of State; his own thoughts were centred on the training of armies and the conduct of campaigns.

The Stadholder of Friesland, William Lewis of

Nassau, the son of John, was the cousin and life-long confidant and adviser of

Maurice, who owed to him his first instruction in military knowledge, and who

could always rely on his far-sighted prudence and discretion. Of blameless

life, sincerely religious, a firm adherent of the Reformed faith, William Lewis

was at the same time broad-minded and statesmanlike in his views of men and

things, like the great uncle whose daughter he married. He was a reformer of

military science on principles drawn from a study of Greek and Roman writers, a

commander of far more than ordinary ability, yet modest withal, aiming always

at the good of the common cause rather than at his own personal fame or

advantage. It was by his counsel and persuasion that the States General at

length consented in 1590 to alter their military policy. Hitherto it had been

assumed as a kind of axiom that the troops of the States could not oppose the

Spaniards in the field; and the efforts of the Netherlanders had been strictly

confined to the defensive. But the army of the States had been transformed by

the assiduous exertions of Maurice and William Lewis both in discipline,

mobility, and armament, and, though composed of a medley of nationalities,

English, Scotch, French, and Germans, as well as Netherlanders, had become, as

a fighting machine, not inferior in quality to its adversaries. William Lewis

had for some time been urging upon the States to take advantage of Parma's

embarrassments by the adoption of offensive in the place of defensive tactics;

and at last, in 1590, at the time of the first expedition of the Duke into

France, the joint efforts of both Stadholders to this

end at length overcame the timidity of the burgher deputies.

1592-5] Death of Parma.—Stadt en Landen.

The tide of the

Spanish advance had already begun to turn in the spring of that year. On March

3, a body of 78 Netherlanders, concealed in a vessel laden with peat, had taken

Breda by surprise. In the autumn Maurice, at the head of a small column, after

failing to capture Nymegen by a coup de main, raided

the whole of North Brabant and took some dozen small places from the enemy. The

year 1591 was a year of surprising triumphs. Zutphen,

unexpectedly attacked, fell into the hands of Maurice and William Lewis after

a five days' siege, on May 20. Deventer was next beleaguered, and, though

gallantly defended by Herman van den Bergh, a cousin of Maurice, surrendered on

June 20. The army then moved upon Groningen; but, on hearing that Parma was

besieging the fort of Knodsenburg, Maurice hastened

to its relief, routed the enemy's cavalry, and compelled him to retire. A

sudden movement southward to Zeeland brought the Stadholder before the town of Hulst in the land of Waas, which surrendered after three days' investment. Then

returning upon his steps the indefatigable leader finished up an extraordinary

campaign by the seizure of Nymegen, October 21. At

the age of twenty-four years, Maurice now took his place among the first

generals of his time.

The next year, 1592, saw Parma once more marching into France for the

relief of Rouen; and the way lay open to the Stadholders for freeing Friesland and the Zuiderzee from the hold of the Spaniard. The

Spanish forces in the north were under the command of their old chief Verdugo, who regarded the two fortresses of Steenwyk and Koevorden as quite

impregnable. The English auxiliaries under Vere had

been sent to France, and Maurice's army was thus weakened. But the Stad-holder's scientific skill in the art of beleaguering

was able to accomplish what was regarded as impossible. Steenwyk fell on June 5, after a gallant defence; and, despite the utmost efforts of Verdugo to raise the siege of Koevorden,

that place also surrendered on September 12.

Shortly afterwards, on December 3, the most redoubtable adversary of the

States was removed by the death of Parma. Broken in spirit, and ill from the

effects of a wound, he had retired to Spa. He had long forfeited the confidence

of the King, and died while on his way to meet the Count of Fuentes, who had

arrived at Brussels with a royal letter of recall Until the arrival of the new

Governor, Archduke Ernest, his post was filled by the old Count of Mansfeld.

The great event of Maurice's campaign of 1593 was the siege and capture

of Geertruidenburg, the only town of Holland in the

possession of the Spaniards which closed important waterways. The conduct of

this siege, sometimes called "the Roman leaguer" from the

astonishing scientific skill with which the methods of the ancients were applied

in the construction of the besieger's lines and approaches, put the crown upon

Maurice's fame. Despite the neighborhood of Mansfeld

with an army of 14,000 men, the town was taken, June 25, after a siege of three

months' duration. In the following year the Stadholder's attention was once more turned to the north. After a two months' siege

Groningen surrendered, under the so-called "treaty of reduction".

This defined the terms on which the town, with the Ommelanden,

became a Province of the Union known as Stadt en Landen. William Lewis was appointed its Stadholder.

Maurice's four offensive campaigns had practically cleared the soil of the

federated Provinces from the presence of the Spanish garrisons; and the

authority of the States General was now established within the defensible

limits of a well-rounded and compact territory.

Archdukes Ernest and Albert. [1595-6

In January, 1595, Henry IV of France had declared war upon Spain, and

sought a close alliance with the United Provinces. Thus Archduke Ernest, as

Viceroy of the Netherlands, found himself in a most difficult position. He had

hostile armies on both sides of him; and the resources of Spain were already

so exhausted, that no money was forthcoming for the payment of troops. In these

circumstances Philip urged the Archduke to make an effort for peace with the

States on equitable conditions upon the lines of the Pacification of Ghent. But

the States were in no mood to accept any conditions which recognized in any

shape the sovereignty of Philip; and the King was unwilling to recognize their independence. The negotiations came to

nothing.

The arrival of Archduke Ernest in the southern Netherlands had been

greeted with enthusiasm. Rumor pointed to his

marriage with the Infanta, and to the establishment

at Brussels of a national government under their rule. But these expectations

were speedily doomed to disappointment by the sudden death of the Archduke

(February 20,1595). His place was taken ad interim by the Count of Fuentes, a

Spanish grandee of the school of Alva, but a very capable commander. His year's

administration of affairs was attended by more success in the field than had

attended the Spanish arms since 1587. The efforts of the allies in Luxemburg,

and along the southern frontier at Cambray and Huy, ended in failure, all the advantages of the campaign

rested with the Spaniards. A serious disaster had meanwhile occurred to a

portion of the States' army under Maurice. The Stadholder had made an attempt to seize Groenloo by surprise,

but the veteran Mondragon had hastened to its relief. For months the two armies

lay watching one another, but without coming to a decisive action. In a chance

encounter, on September 1, a small troop of cavalry, sent out by Maurice to

intercept a body of Spanish foragers, was completely defeated; and its leaders,

Philip of Nassau, brother of the Stadholder of

Friesland, and a brilliant scion of his House, and his cousin Ernest of Solms, were killed. Ernest of Nassau, Philip's brother, was

taken prisoner.

At the beginning of 1596 Fuentes was replaced as Governor by

Cardinal Archduke Albert of Austria, the favourite nephew of Philip, a far more capable man than his brothers, both as statesman

and soldier. He brought with him reinforcements and some money, and, finding

the army well disciplined and ready for action, he resolved to emulate, if

possible, the successes of the previous year. But Fuentes had departed; and

both Verdugo and Mondragon had died immediately

before his arrival. In the lack of Spanish generals of repute, Albert gave the

command to a French refugee, the Seigneur de Rosne.

At this time a considerable body of the States' troops were with Henry IV, who

was besieging La Fère. His lines were so strong that

it seemed hopeless to attempt to raise the siege by a direct attack. But, acting

on the advice of Rosne, Albert's army suddenly

advanced upon Calais, which was unprepared and quickly surrendered to the

Spaniards. It was a heavy and humiliating loss to the French, for which the

capture of La Fere offered scant compensation. The

Archduke, by the recapture of Hulst, followed up this

striking success. Maurice had been so weakened by the detachment of his troops

serving in France, that he had been unable to attempt any offensive operations.

Nor was he able to prevent the powerful Spanish army from effecting the capture

of Hulst, dearly purchased by 5000 lives, including

that of Rosne himself.

Albert, like his predecessor, had begun with futile peace overtures. The

States General on the contrary were at this time engaged upon other negotiations,

the issue of which marked a stage in the history of the United Provinces.

Before the close of the year there was concluded between England, France, and

the States, a triple alliance, which had to be purchased by hard conditions,

but which proclaimed the recognition by England and France of the United

Provinces as a free and independent State. The States General undertook to

maintain an army of 8000 men in the Netherlands, to send an auxiliary force of

4000 men to France, and lastly to give up the privilege, so important to the

mercantile classes in Holland, of free trade with the enemy. The consent of the

States of Holland to this requirement was obtained only with the greatest

difficulty; and after it had been conceded it was systematically evaded. The

traffic with Spain and Portugal was still carried on clandestinely; and, as

the alliance was but of short duration, the forbidden

trade was soon almost as vigorous as ever. The States in fact quickly found

that their allies had agreed upon a secret treaty behind their backs, and that

it was necessary for them to look carefully to their own interests.

1596-8] The great campaign of 1597.

Meanwhile,

it was not the fault of the Netherlanders that the results attained were not

more considerable. At hardly any stage of his career did the brilliant military

talents of Maurice shine more conspicuously than in the campaign of 1597. It

began with the astonishing victory of Turnhout. Near

that village lay a considerable force under the command of an officer named Varax, which ravaged the neighborhood far and near. In January, while the armies were still in their winter quarters,

Maurice, at the head of a body of troops rapidly collected from various

garrison towns, set out with such secrecy and despatch that he arrived quite unexpectedly within a few miles of Varax camp. The Spanish General determined to effect a retreat under cover of the

night. Maurice set out in pursuit with his cavalry only, and a couple of

hundred musketeers mounted behind the riders, less than 800 men in all. He came

up with the enemy, just in time to prevent their making their escape behind a

morass, and at once gave orders to charge. Varax did

his utmost to draw up his wearied troops in order of battl; but no time was

given him, and the rout was complete. In half-an-hour all was over. Out of a

force of some 4500 men, 2000 were killed, among them Varax himself; 500 prisoners were taken and 28 standards. Maurice lost only eight or

ten men, and was back at the Hague within a week, having freed North Brabant

and Zeeland from the incursions of the enemy.

The summer campaign was one long succession of triumphs for the States.

The Archduke had not enough money to maintain a large army on both his northern

and his southern frontier, and had resolved to direct his chief attention to

the French side. Henry IV was in even worse want of means; and the capture by

the Spaniards of Amiens, with a quantity of stores, was a severe blow to him.

But the way was now open to Maurice for prosecuting siege after siege without

fear of interference. Rheinberg, Meurs, Groenloo, Breedevoort, Enschede, Oot-marsum, Oldenzaal, and Lingen all fell

into his hands, and a very large district was added to the territory

acknowledging the authority of the States General.

The advantages of the French alliance, however, had ceased before the

opening of another campaign on May 2, 1598. Henry concluded peace with Philip

at Vervins. In vain the States had done their utmost

to prevent this result. They were more successful with Elizabeth, to whom they

sent an embassy, in which Oldenbarneveldt personally

took part. She consented to continue the war with Spain on condition that the

States repaid by instalments her loan to them, and

agreed to send a large force to England in case of a Spanish invasion. On the

other hand she consented henceforth to have only one representative on the

Council of State, and to allow the English troops in the service of the

Netherlands, including among these the garrisons of the cautionary towns, to

take the oath of allegiance to the States General.

Marriage of Albert and Isabel. [1598

It had been for some time

the intention of Philip to marry his eldest daughter, Isabel Clara Eugenia, to

her cousin, Archduke Albert, and to erect the Netherland Provinces into a

sovereign State under their joint rule. Philip wished to conciliate the

Netherlander by conceding to them the appearance of independence; but the

contract, and a secret agreement which accompanied it, was intended not only to

secure the reversion of the Provinces to the Crown of Spain in case the

Archduke should be childless, but to keep them in many respects subordinate to

Spain, and under Spanish suzerainty. Philip was undoubtedly prompted to take

this step, in the first place by affection for a daughter to whom he was deeply

attached; and in the second place by his sincere zeal for the Catholic faith.

Both Albert and Isabel possessed many qualities which fitted them for the

difficult task.

In May the instrument was signed which erected the old Burgundian

Provinces into a separate State under the rule of a descendant of Charles the

Bold. In September Philip II died. In November the Archduke Albert, who had

resigned his ecclesiastical dignities, was married by proxy to the Infanta, who was still in Spain. The old régime had passed

away.

The hopes of reunion and of peace placed upon the advent of the

Archdukes were speedily dissipated. Even in the south the new sovereigns were

received without enthusiasm and with suspicion. It was felt that a government

was being set up, imbued with Spanish ideas, guided by Spanish councillors, and relying on Spanish garrisons. The war and

the Inquisition had effectually crushed out all life and enterprise in the

southern Provinces; and the mere presence of a resident Court and

well-intentioned rulers at Brussels could do little to restore a ruined and

desolate land. Very different was the state of things north of the Scheldt.

Here the long struggle for existence had filled the people with a new spirit,

and, so far from bringing in their train exhaustion and misery, the very

burdens of the war had been productive of unexampled prosperity. Nothing in

history is more remarkable than the condition of the United Provinces, and

especially of the Provinces of Holland and Zeeland, at the end of thirty years

of incessant warfare.

1587-1601] Prosperity of the United Provinces.

They had become the chief trading country of the world. The riveting of

the Spanish yoke upon Brabant and Flanders by the arms of Parma had driven the

wealthiest and most enterprising of the inhabitants of Antwerp, Bruges, and

Ghent to take refuge in Holland and Zeeland, whither they brought with them

their energy, their commercial knowledge, and their experience of affairs. The

Hollanders and Zeelanders were above all things

sea-faring folk; and their industries had up to the time of the revolt been all

connected with the sea. Their fisheries, and especially the herring fishery,

employed many thousands of boats and fishermen, and were a great source of

wealth. They were the carriers whose ships brought the corn and the timber from

the Baltic, the wines from Spain and France, the salt from the Cape Verde

Islands, to the wharves and warehouses of the Zuiderzee and the Meuse, and

again distributed them to foreign markets. Had the Hollanders and Zeelanders not been able to keep the seas open to their

ships, the revolt must have collapsed very speedily. As it was, their trade

with each succeeding year grew and prospered. Even the Spaniards themselves

were dependent upon their hated enemies for the very necessities of life; and

the Dutchmen did not scruple to supply their foes when it was to their own

profit. Thus trade thrived by the war, and the war was maintained by the wealth

poured into the country, while the crushing burden of the taxes was lightened

by the product of the charges for licenses and convoys, which were really paid

by the foreigner. Commerce became a passion with the Hollanders and Zeelanders; and eagerness after gain by the expansion of

trade possessed itself of all classes. The armies commanded by Maurice were

mainly composed of foreigners; the Netherlanders themselves made the sea their

element. In 1587 800 vessels passed through the Sound for corn and timber. In

1590 the Dutchmen, not content with carrying the corn as far as Spain

southwards, penetrated into the Mediterranean and supplied Genoa, Naples, and

other Italian towns with their commodities; and shortly afterwards they made

their way to Constantinople and the Levant, under a permit from the Sultan

obtained by the good offices of Henry IV. So greatly had this trade grown by

the end of the century that in 1601 between 800 and 900 vessels sailed from

Amsterdam for the Baltic to fetch corn within three days. Scarcely less remarkable

was the expansion of the timber trade. In 1596 the first saw-mill was erected

at Zaandam. During the decade that followed, the shores of the Zaan became the staple of the timber trade of Europe. At

the neighbouring ports of Hoorn and Enkhuysen shipbuilding attained a perfection unknown in other lands. The cloth and the linen trades also flourished, introduced by

the skilled Flemish weavers, who fled from persecution to Leyden and Haarlem.

English cloth was imported to Holland to be dyed, and was sold as Dutch.

Nor was the enterprise of this nation of traders confined to the

European seas. The Gold Coast of Africa, both the Indies, and even distant

China, allured adventurers to seek in these distant regions, at the expense of

the hated Spaniard, who claimed the monopoly of the Oceans East and West alike,

fortunes surpassing those which were made in Europe. A certain Balthasar de Moucheron, a

merchant of French extraction, who had been settled at Antwerp and fled from

that city to Middelburg at the time of

its capture by Parma, was the pioneer in these first efforts at a world-wide

expansion of commerce. His earliest attempt was directed to the opening out of

trade with Russia. In 1584 he established a factory at Archangel on the White

Sea. This intercourse with the far North led to a scheme for reaching China and

the East by the route of northern Asia, for which, after laying his plans

before the Stadholder and the Advocate, Moucheron secured the support of the States of Holland. In

1594 two small vessels sailed from the Texel under Willem Barendsz; they succeeded in passing through the Waigaats in

open water, but were quickly stopped by ice. Undeterred by the failure a larger

fleet, under Heemskerk and Barendsz,

in 1596 essayed the same venture. Amidst incredible sufferings the winter was

passed on the inhospitable shores of Nova Zembla. Barendsz himself perished, but a remnant under Heemskerk made their escape home. The effort again was

fruitless; but the story of these brave men's wintering in the frozen polar

seas fascinated their contemporaries.

Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563- 161) is credited with copying top-secret Portuguese nautical maps thus enabling the passage to the elusive East Indies to be opened to the English and the Dutch. This enabled the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company to break the 16th century monopoly enjoyed by the Portuguese on trade with the East Indies. |

|

The first voyage to the Gold Coast of Guinea was undertaken by Barent Erikszen of Medemblik, in 1593; and from this time forward an ever

increasing number of ships made their way to the various river mouths of the

bight of Guinea, and established friendly relations and a lucrative trade with

the natives of the country. The first actual conquest on this coast was made by

a large expedition despatched in 1598 by Balthasar de Moucheron for the

seizure of the island Del Principe. But, before this, the daring enterprise of

the two brothers Houtman had carried the Netherlands

flag to the shores of India and the Malay Archipelago. The way thither was no

secret, for numerous Dutch sailors served on Portuguese ships, and had thus

learned the route to Mozambique, Goa, and Molucca.

The Itinerarium of the famous traveller,

Jan Huyghen Linschoten, a

native of Enkhuysen, who spent five years in the East

Indies, aroused universal interest. Already during the period of the Leicester

régime Linschoten found many of his countrymen

occupying positions of trust in various parts of the far East. Linschoten, in 1594, went out as Commissary of the States

of Holland on the first expedition sent by Moucheron to discover the North-West Passage; and at this very time another expedition

was being prepared by certain Amsterdam merchants to sail direct for the Indies

by the usual route round the Cape. The moving spirit of this voyage was Cornelis Houtman of Gouda (1565–1599), who,

like Linschoten, had been in the Portuguese ships,

and who, as upper commissary, was in command of the four vessels which set sail

on April 2, 1595. They visited Madagascar, Java, Goa, and Molucca with varied fortunes, and after many dangers and hardships reached Amsterdam

once more in July, 1597. Several small Companies were now formed for exploiting

the rich regions which had for so long been the preserve of the

Portuguese: three at Amsterdam, two at Rotterdam, two in Zeeland, one at Delft.

In 1598 no less than eight large East India merchantmen were despatched by three of these Companies. A new source of

national wealth had been discovered, and the only fear was that the trade would

be ruined by the unlimited competition. Hitherto the principle of Dutch

commerce had been that of absolute free trade.

|

1593-1601] Foundation of the East India Company.

Now for the first time a

monopoly was created under the auspices of Oldenbarneveldt,

and by the efforts of the States of Holland a Charter was, on March 20, 1601,

granted to an East India Company for twenty-one years. This Company received,

under certain restrictions, the exclusive right of trade to the East Indies

under the protection of the States General, and was allowed to erect factories

and forts, and to make alliances and treaties with the native princes and

potentates, appoint governors, and employ troops. The Company was divided into

Chambers, corresponding to the various small Companies, which had been

amalgamated. The supreme government lay with a body, known as the Seventeen, on

which Amsterdam had eight representatives, Zeeland four, the Meuse and North

Quarter each two, the last three having the right of jointly electing a third

member. This great Company thus came into existence a short time before its

English rival, and has the distinction of being the first of all Chartered

Companies, and the model imitated by its many successors.

Not content even with

this extension of the sphere of their commercial enterprises and its vast

possibilities, the eyes of the keen and eager traders were already turning

westward as well as eastward. Netherlanders had first made acquaintance with

the West Indies and Brazil in the Spanish or Portuguese service; and in 1593 Barent Erikszen, in his voyage to

Guinea, had proceeded across the Atlantic to Brazil. It was, however, the fame

of Ralegh's voyages, and his account of the Golden

city of Manoa and the fabled riches of Guiana that

spurred on the imagination of the adventurous Hollanders and Zeelanders with feverish dreams of untold wealth, and led

them to follow in his steps. Moucheron was again

among the pioneers; and Dutch trading ships laden with articles of barter were

to be found entering the Amazon, coasting along the shores of Guiana, and

returning with cargoes of salt from the mines of Punta del Rey beyond the

Orinoco. A certain Willem Usselincx, also a Flemish

refugee, first began to make his name known in the last decade of the sixteenth

century as a strenuous advocate for the creation of a chartered West India

Company. He did not succeed at this time; but for a quarter of a century he

gave himself unceasingly to the task of urging upon the authorities the

advantages and profits to be obtained by the establishment of colonies upon the

American continent.

Thus, then, their war for life and death had stirred the sluggish blood

of the Dutch people, and had aroused in them a most extraordinary spirit of

energy and enterprise. Peace overtures, unless accompanied by the concession of

all their demands, were unlikely to find acceptance among traders thriving at

the expense of their enemies, and dreading lest the cessation of warfare should

close to them their best markets.

The Archdukes in Brussels. [1599-1600

Albert and Isabel did not make their joyeuse entrée into Brussels until the close of 1599.

During the absence of the Archduke the Spanish armies had been under the

command of the Admiral of Aragon, Mendoza, who, making the duchy of Cleves his

head-quarters, had mastered Wesel, Rheinberg and

other strong places on the Rhine. The eastern Provinces were still mainly

Catholic, and contained many Spanish sympathisers;

but, in spite of disputes and discontents in Friesland, and still more in

Groningen, Maurice at the head of a small army more than held his own. The

difficulty of raising taxes in these Provinces, and also in Drenthe,

Overyssel, and Gelderland, inclined the States General and the States of

Holland during 1599 to content themselves with defensive warfare. In the

following year, however, it was determined to raise a large force for offensive

operations, and to undertake an invasion of Flanders with a view to the capture

of Dunkirk. This seaport had for years been a nest of audacious pirates, who,

by lying in wait for the Dutch merchantmen in the narrow seas, had become a

constantly increasing menace and danger to navigation. All efforts to check the

corsairs by armed force had proved in vain, though in the fierce fights which

took place no quarter was given or taken. For the extirpation of the pirates by

means of a land attack, an army of 12,000 men was embarked at Rammekens June 21, 1600, under the command of the Stadholder. The plan was to convey the troops by sea direct

to Ostend, which had always throughout the war remained in the hands of the

States, and was their sole possession in Flanders; hence to march straight

along the sea-shore and, after capturing Nieuport, to

use it as a base for the further advance on Dunkirk.

Curiously enough, this bold scheme of operations was proposed and

carried out by the States General-in other words, by Oldenbarneveldt,

who was supreme in that Assemblyn, in spite of the opposition of Maurice and

William Lewis, both of whom, together with all the other experienced military

leaders, were adverse to so extremely hazardous an enterprise. Oldenbarneveldt had persuaded their High Mightinesses that the moment was opportune for such a

stroke, because a large part of the Archduke's troops were in open mutiny for

lack of pay, and it was known that he had no funds for satisfying them.

Maurice, on the other hand, believed it unsafe to denude the United Provinces

of their entire field army, and expose it, when far away from its base in an

enemy's country, to the risk of being cut off and possibly destroyed. The

States General, however, persisted; and Maurice now set to work with his usual

thoroughness. At his request, however, a deputation of the States General took

up their residence in Ostend, to share the responsibility of the commander.

Difficulties arose from the outset. Prevented from sailing by contrary winds,

the army was forced to land in Flanders at Sas de

Ghent, and to march by land to Nieuport. On June 27,

the fort of Oudenburg was taken, and a garrison left

in it; on July 1, Maurice reached Nieuport and

proceeded to invest the town.

1600] Campaign against Dunkirk.

Meanwhile the Archdukes had not been idle. By

lavish promises Albert and Isabel succeeded in winning back the mutineers; and

with great rapidity 10,000 foot and 1500 cavalry were gathered together, all of

them seasoned troops. With this army the Archduke quickly followed on the

tracks of Maurice, seized Oudenburg by surprise on

July 1, and thus cut off the communications of the Stadholder with Ostend and the United Provinces. The news of the rapid approach of the

enemy was brought to Maurice by a fugitive. It found the States' army separated

into two parts by the tidal creek which formed the harbour of Nieuport, and which could only be crossed at low

water. A few miles to the north a small marshy stream over which on the

previous morning Maurice had thrown a bridge at Leffingen,

entered the sea. He now despatched his cousin Ernest Casimir with 2000 infantry, Scots and Zeelanders,

and four squadrons of cavalry, to seize the bridge and hold it against the

Archduke, until he was able to extricate the main body of the States' army from

their dangerous position. When Ernest Casimir arrived

at Leffingen, the bridge was already in Albert's

hands; but he drew up his small force in battle order on the downs to check

the further advance of the Spaniards. Then ensued one of those unaccountable

panics which sometimes seize the bravest soldiers. The Dutch cavalry turned

their backs at the first onset; and their example infected the infantry, who,

throwing away their arms, rushed along the downs and on to the beach in

headlong flight. Upwards of 800 were butchered or drowned, the chief loss

falling upon the Scots. The sight of vessels putting out of the harbor of Nieuport, and the

argument that never yet had Netherlanders withstood

the Spanish veterans in the open field, determined Albert to give the order to

advance. Meanwhile the ebb had enabled Maurice to march his troops across the

haven and draw them up in line of battle on the downs. The ships that had been

seen by the Spaniards were his transports, sent by him out of the harbor probably to save them from the risk of being set on

fire by the garrison of Nieuport, while he and his

army were fighting on the downs. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon of July 2 the

battle was formed. A brilliant charge of the States' cavalry under Lewis Günther of Nassau opened the proceedings, and then the

solid mass of the Spanish and Italian foot, veterans who had conquered in many

a hard-fought field, fell upon the vanguard of Maurice's army, consisting of

2600 English and 2800 Frisians under Sir Francis Vere.

For more than three hours every hillock and hollow of the sandy dunes was

contested on both sides hand to hand; backwards and forwards the conflict

flowed, until at last the gallant Vere himself was

carried from the field severely wounded. Then the Englishmen and Frisians

slowly gave way, foot by foot, with their faces still to the foe.

Lewis Gunther's cavalry attempted to relieve

them by a fierce charge; but it was driven back in confusion, and when the

Archduke, who had been in the thick of the fight all day, ordered up his

reserves, the States' army began to retire in disorder. All seemed lost. But

Maurice, conspicuous by his orange plumes, threw himself into the ranks of the

fugitives, and succeeded in rallying a portion of his troops. The effect was

instantaneous, for their adversaries in their turn were thoroughly worn out by

their two battles in the same day. A momentary pause in their advance enabled

Maurice, with the keen eye of a great captain, to hurl upon their flank three

squadrons of cavalry that he had kept as a last reserve. Scarcely offering any

resistance the army of the Archduke fell into inextricable confusion, turned

their backs and fled. Albert himself only just succeeded in making his escape

to Bruges. Of his army 5000 were killed, above 700 were made prisoners, among

them a number of distinguished officers, including Mendoza, and 105 standards

were taken. Thus Maurice and his army were saved from the very jaws of

destruction. But though the fame of the victory, which showed that even in the

open field the dreaded Spanish infantry were not invincible, spread through

Europe, it was in reality a barren triumph. In spite of the opposition of the

States, Maurice resolved to run no more risks. He led back his army to Holland,

and attempted no further active operations. At this time were sown the seeds of

the unhappy dissension between the Stadholder and the

Advocate.

During the next three years the siege of Ostend (July 15, 1601-September

20, 1604) occupied the energies of both combatants. The Archduke Albert had

made up his mind to capture this seaport, which in the hands of the Dutch was a

perpetual thorn in the side of Flanders. But the town was open to the sea, and

was continually supplied from Zeeland with provisions, munitions, and

reinforcements. Its first Governor, Sir Francis Vere,

was followed by a succession of brave and capable men, the majority of whom

died fighting. Never was a more valorous defence, never a more obstinate

attack. It was a long story of mines and counter-mines, of desperate assaults

and bloody repulses, of fort after fort captured, only to find fresh forts and

new lines of defence constructed by the indefatigable garrison. The efforts of

Maurice in 1601 were confined to the recapture of the Rhine fortresses, Rheinberg and Meurs. In 1602 the

important stronghold of Grave on the Meuse surrendered to him after a two

months' siege. In the autumn of 1603 Marquis Ambrosio de Spinola assumed command of the Spanish forces

before Ostend. He was a rich Genoese banker, who, though without any experience

of war, had offered his services and his money to the Archdukes, promising them

that he would take Ostend. He kept his word. With a reckless expenditure of

life, what was left of the town fell piece by piece into his hands. At length,

in April, 1604, the Stadholder yielded somewhat

sullenly to the pressing requests of the States General, and led an army of

11,000 men into Flanders, seeking to relieve the pressure upon Ostend, by

laying siege to the equally important seaport of Sluys.

It fell into his hands in August. Ostend was now at its last gasp, and the Stadholder was ordered to essay its relief by a direct

march against Spinola's investing army. Maurice and

William Lewis protested, but their protests were overruled. Before, however,

they began to march southwards, Ostend had been surrendered, September 20. The

town had already ceased to exist; and Spinola found

himself after all the master of a heap of confused and hideous ruins. The siege

had lasted three years and seventy-seven days, and had cost the Archdukes,

according to some authorities, the lives of more than 70,000 soldiers. The

gallant defenders had succeeded in draining away the main strength of the

Belgian forces, and in exhausting the resources of the Brussels treasury; and

before they had surrendered the poor little town on the sand dunes with its

miserable harbor, the States had in Sluys possessed themselves of another Flemish seaport, far

more commodiously situated, arid enabling them to command the southern entrance

to the Scheldt. Sluys was strongly garrisoned; and

Frederick Henry, Maurice's younger brother, now twenty years of age, was

appointed its Governor.

The military events of the next two years require but the briefest

notice. The States were now isolated. James I of England had concluded a treaty

of friendship with the Archdukes. Henry IV of France was lukewarm. Maurice was

now confronted by an active and exceedingly able young general, Spinola, whose army had confidence in its leader, and,

being regularly paid at his cost, followed him cheerfully. The policy of the Stadholder, who since the Nieuport campaign had been on far from friendly relations with Oldenbarneveldt and the States General, was strictly defensive. Yet such was the skill and vigour of Spinola that even in

this Maurice was scarcely successful. The two armies faced each other for some

time in the neighborhood of Sluys,

when, at the end of July, the Marquis made a sudden and rapid march northwards

towards Friesland. Spinola captured Oldenzaal and Lingen before

Maurice was able to relieve these towns; and, had he pressed on to Coewarden, it would probably have fallen into his hands,

and the north-eastern Provinces would have lain at his mercy. But he paused in

his march, perhaps from lack of supplies, and finally retreated towards the

junction of the Rühr with the Rhine. While halting

here, an attempt was made by Maurice on October 8,1605, to surprise an isolated

body of Italian cavalry. But a sudden panic seized the States' troops, and

despite the desperate exertions of Frederick, Henry, who, at the risk of his

life, succeeded in rallying some of the flying troops, a sharp and humiliating

reverse closed the campaign. The events of 1605 certainly damaged the Stadholder's reputation.

A severe illness kept Spinola from the front

the whole of the next spring; but in June he set out with the intention of

forcing the passage of the Waal or the Yssel, and

making an inroad into the very heart of the United

Provinces. He was thwarted partly by the skillful defensive positions taken up

by Maurice, but still more by a season of continuous rain, which turned the

whole country into a morass. Foiled in his main purpose Spinola laid siege in succession to Groll and Rheinberg, both of which were taken, without any attempt on

the part of Maurice to relieve them. His conduct throughout these operations

excited some censure both among friends and foes; but his Fabian tactics were

undoubtedly advantageous to the interests of the States. For the Brussels

treasury was empty, Spinola's personal credit

exhausted, and mutiny rife among his troops. Moreover it was on sea, and not on

land, that the most damaging blows could be struck at the unwieldy empire of

Spain.

The operations of the East India Company had been on a large scale, and

had been attended with much success. Not merely had the monopoly of Spain and

Portugal in the Orient been invaded, but their dominion there had been

seriously shaken. A great fleet of seventeen vessels under the command of

Admiral Warwyck and Vice-Admiral de Weert sailed in 1602, and was absent for more than five

years. All the principal islands of the Malay Archipelago, as well as Ceylon,

Siam, and China, were visited. In 1604 another expedition of thirteen ships,

under Steven van der Hagen, was sent to Malabar and

the Moluccas. Factories were established and ports built at Amboina, Tidor, and other places ; and the fleet returned in 1606

with a very rich cargo of cloves and other spices. On his return voyage van der Hagen met at Mauritius a third outward-bound fleet of

the Company, under Cornelis Matelief.

This force consisted of eleven small armed ships, manned by 1400 sailors. In

the summer of 1606 Matelief laid siege to the

Portuguese fortress of Malacca, situate in a commanding position at the

southernmost extremity of the Malay Peninsula. Here he was attacked on August

17 by Alphonso de Castro, the Spanish Viceroy of

India, at the head of a vastly superior fleet, consisting of eighteen galleons

and galleys, carrying 4000 to 5000 soldiers and sailors. A fierce but

indecisive action resulted in the first instance in the raising of the siege of

Malacca. On hearing, however, that de Castro had sailed away, leaving only ten

ships in the roadstead of Malacca for the defence of the place, Matelief returned, and, on September 31, fell Upon the

Spaniards. One of the most complete victories in naval records was the result.

Every single vessel of the enemy was destroyed or burnt, while the Dutch

scarcely lost a man. After visiting China, and establishing the authority of

the Company at Amboina, Tidor, Ternate, Bantam, and

other places, Matelief left the further conduct of

affairs in Eastern waters to Paul van Kaarden, who

met him at Bantam at the head of yet another fleet, while he himself returned

home with five ships, laden with spices, bringing into the midst of peace

negotiations the great tidings of his adventures and victories.

1606-7] Heemskerk's victory at Gibraltar. Peace negotiations.

Nor were the maritime triumphs of the Netherlander confined to distant

oceans. As their fleets returned, laden with rich cargoes, along the West Coast

of Africa, they had to run the gauntlet of Spanish and Portuguese squadrons,

suddenly putting out from Lisbon or Cadiz or other Iberian ports. After voyages

extending over two or more years the East Indiamen, by the time they passed the

Straits, were no longer in good seaworthy condition or fighting trim, and thus

ran a constant risk of falling an easy prey to their enemies. In 1607 news

reached the States of the gathering of a large Spanish fleet at Gibraltar,

supposed to be destined for the East Indies; and under pressure from the

directors of the East India Company the States determined to equip a large

expedition with the object of either intercepting this fleet or attacking it in

the Spanish harbor. Early in April twenty-six

vessels set sail under the command of Jacob van Heemskerk,

the hero of the Nova Zembla wintering, and one of the

bravest and most skillful of Dutch seamen. He was a man gentle and quiet in

private life, but the joy of battle was as the very breath of his nostrils. He

found anchored in Gibraltar Bay the entire Spanish fleet of twenty-one vessels,

ten of them great galleons, beside which the Dutch ships seemed mere pigmies.

The Spanish Admiral d'Avila was likewise an

experienced veteran, who had fought at Lepanto. Heemskerk at once gave the order to attack, and directed that each of the great galleons

should be assailed by two Dutch ships, one at each side. Heemskerk laid his own flagship alongside that of d'Avila, and

so opened the fight. At the very beginning of the struggle both Admirals were

killed. But Heemskerk's death was concealed, and his

comrades carried out his instructions, and fought with desperate resolution in

his own ship to avenge his loss, in the others as if the eye of their chief had

been still upon them. The victory was complete, and the Spanish fleet was

annihilated. Between two and three thousand of their crews perished. On the Dutch

side no ship was destroyed, and only about a hundred sailors were killed. This

crushing and humiliating disaster to the Spanish arms had a powerful effect in

hastening forward the negotiations for peace, in which both parties, now

thoroughly weary of war, were at the time seriously engaged.

The first step had been taken by the Archdukes, who secretly despatched Father Neyen, Albert's

Franciscan confessor, to open relations with Oldenbarneveldt and the Stadholder. The States, however, refused to

enter into negotiations of any sort, unless they were treated as a free and

independent Power. The Archdukes therefore at length consented to negotiate

with the United Provinces "in the quality and as considering them free

Provinces and States, over which they had no pretensions", subject to the

ratification of the King of Spain within three months. They offered to

negotiate either on the basis of a peace, or for a truce for twelve, fifteen,

or twenty years. Meanwhile, it was arranged that an armistice for eight months

should be concluded, Heemskerk's fleet recalled, and

no military operations of any kind carried on.

At the very beginning of the

negotiations it was clear that in the United Provinces there was much division

of opinion. On the side of peace stood Oldenbarneveldt, and with him a majority of the burgher regents, who believed that the

land could no longer bear the burden of taxation, and that the prosperity which

had attended commerce in war-time would be largely increased by peace, so long

as sufficiently favorable terms as to liberty of

trading could be secured. At the head of the war party was Prince Maurice, with

William Lewis of Friesland, the military and naval leaders, and a considerable

number of the leading merchants. Maurice had lived in camps from boyhood; his

fame had been won, not in the Council Chamber, but at the head of armies. Peace

for him meant enforced idleness and great loss of emoluments. Still, though not

uninfluenced by personal motives, both he and William Lewis were far too good

patriots not to put on one side any purely selfish reasons for opposing that

which they believed to be to the advantage of the land. But they and those who

thought with them did not trust the Spaniard. They did not believe that peace

could be obtained without closing the Spanish Indies, East and West, to Dutch

trade; and, with numbers of their countrymen, they dreaded lest the southern

Netherlands should once more become formidable commercial rivals, and Antwerp

again, as a seaport, vie with and perhaps surpass Amsterdam.

At last, in October, 1607, it was signified that the King agreed to

treat with the States as independent parties, but on condition that religious

liberty to Catholics should be conceded during the negotiations. The document

was in many points far from pleasing to the States, but by the exertions of the

French Ambassador, President Jeannin, and his

English colleague, difficulties were smoothed away, and at last, on February 1,

1608, the envoys from Brussels arrived in Holland, with a brilliant retinue. At

the head of the deputation were Spinola and Richardot, the president of the Archduke's Privy Council.

The stately procession was met near Ryswyk by the Stadholders, Maurice and William Lewis of Nassau, attended

by a splendid suite. The two famous Generals greeted one another with much

ceremony and courtesy, and side by side made their entry into the Hague. The

States General appointed as Special Commissioners to represent the United

Provinces, Count William Lewis of Nassau and Walraven,

Lord of Brederode, and with them were associated a deputy from each of the

seven Provinces under the leadership of Oldenbarneveldt,

as the representative of Holland. The envoys of France, England, Denmark, the

Palatinate, and Brandenburg took an active part in the discussions; and it was

largely owing to the skill and sagacity of Jeannin that in spite of almost insuperable difficulties an agreement was eventually

arrived at.

1608] Conferences and discussions at the Hague.

The admission of the independence and sovereignty of the United

Provinces met with less opposition on the part of the Archdukes than was

expected. Their policy, though not openly avowed, was to conclude a truce, not

a peace, and thus to leave the dispute as to the sovereignty over the Provinces

to the arbitrament of a future war. It was a

concession intended to be temporary, made with the object of gaining time for

recruiting their ruined finances and gathering fresh resources, so as to renew

hostilities at a favorable opportunity. Richardot raised no difficulties as to the declaration of