|

|

|

Chapter 1MEDICEAN ROME.

ON the 18th of August, 1503, after a sudden

and mysterious illness Alexander VI had departed this life to the unspeakable

joy of all Rome, as Guicciardini assures us. Crowds thronged to see

the dead body of the man whose boundless ambition, whose perfidy, cruelty, and

licentiousness coupled with shameless greed had infected and poisoned all the

world. On this side the Alps the verdict of Luther’s time and of the centuries

which followed has confirmed the judgment of the Florentine historian without

extenuation, and so far as Borgia himself was concerned doubtless this verdict

is just. But today if we consider Alexander’s pontificate objectively we can

recognize its better sides. Let it pass as personal ambition that he should

have been the first of all the Popes who definitely attempted to create a

modern State from the conglomerate of the old Stati Pontificii, and that he should have endeavoured, as he

undeniably did, step by step to secularize that State and to distribute among

his friends the remaining possessions of the Church. But in two ways his

government shows undeniable progress, in the midst of constant tumult, during

which without interruption tyranny succeeded to tyranny in the petty States,

when for centuries neither life nor property had been

secure, Cesare Borgia had established in the Romagna an ordered

government, just and equal administration of the laws; provided suitable

outlets for social forces, and brought back peace and security; and by laying

out new streets, canals, and by other public works indicated the way to improve

agriculture and increase manufacture. Guicciardini himself recognizes

all this and adds the important comment, that now the people saw how much

better it was for the Italians to obey as a united people one powerful master,

than to have a petty despot in every town, who must needs be a burden on the

townsfolk without being able to protect and help them. And

here Guicciardini touches the second point which marks the

pontificate of Alexander VI, the appearance, still vague and confused, of the

idea of a future union of the Italian States, and their independence of foreign

rule and interference. Alexander played with this great political principle,

though he did not remain faithful to it; to what could he have been faithful?

Was not his very nature immoral and perfidious to its core? But now and then at

least he made as if he would blazon on his banner the motto Italia farà da se; this brought him a popularity which

nowadays it is hard to understand, and made it possible for him, the most

unrighteous man in Italy, to gain the victory over the most righteous man of

his time and to stifle Savonarola’s reforming zeal among the ashes at the

stake.

The idea of a great reformation of the

Church in both head and members had arisen since the beginning of the

thirteenth century, and was the less likely to fade from the mind of nations

since complaints of the evils of Church government were growing daily more

serious and well-grounded and one hope of improvement after another had been

wrecked. No means of bringing about this reform was neglected; all had failed.

Francis of Assisi had opposed to the growing materialism and worldliness of the

Church the idea of renunciation and poverty. But Gregory IX had contrived to

win over the Order founded by the Saint to the cause of the Papacy, and to set

in the background the Founder's original purpose. Thrust into obscurity in the

inner sanctuary of the Order, this purpose, tinged by a certain

schismatic colouring, developed in the hands of the Spirituales into the Ecclesia Spiritualis as opposed to the Ecclesia Carnalis, which stood for the official Church. Traces

of this thought are to be found in Dante; we may even call it the

starting-point, whence he proceeds to contrast his Monarchia with

the political Papacy of the fourteenth century, and as a pioneer to develop

with keen penetration and energy the modern idea of the State. The opponents of

the Popes of Avignon in reality only fought against their politics without

paying any attention to the moral regeneration of Christendom. Theological

science in the fifteenth century raised the standard of reform against the

dependence of the Papacy, the triple Schism, and the disruption of the Church.

But she too succumbed, her projects foiled, at the great ecclesiastical

conferences of Constance and Basel. Asceticism, politics, theology had striven

in vain; the close of the Middle Ages on both sides of the Alps was marked by

outbursts of popular discontent and voices which from the heart of the nations

cried for reform, prophesying the catastrophe of the sixteenth century. None of

these voices was mightier than Savonarola’s, or left a deeper echo. He was the

contemporary and opponent of the men who were to give their name to this epoch

in Rome’s history.

The House of the Medici passes for the

true and most characteristic exponent of the Renaissance movement. We cannot

understand the nature and historical position of the Medicean Papacy

without an attempt to explain the character and development of this movement.

The discovery of man since Dante and Giotto, the discovery of Nature by the

naturalism of Florence, the revival of classical studies, and the reawakening

of the antique in Art and Literature are its component parts; but its essence

can only be grasped if we regard the Renaissance as the blossoming and

unfolding of the mind of the Italian people. The early Renaissance was indeed

the Vita Nuova of the nation. It is an error to believe

that it was in opposition to the Church. Art and the artists of the thirteenth

century recognized no such opposition. It is the Church who gives the artists

employment and sets them their tasks. The circle of ideas in which they move is

still entirely religious: the breach with the religious allegory and symbolism

of the Middle Ages did not take place until the sixteenth century. In the

fourteenth century the spread of naturalistic thought brought about a new

conception of the beauty of the human body; this phase was in opposition to the

monastic ideal, yet it had in it no essential antagonism to Christianity. It was

a necessary stage of the development which was to lead from realism dominant

for a time to a union of the idealist and realist standpoints. Many of the

Popes were entirely in sympathy with this Renaissance; several of them opposed

the pagan and materialistic degeneration of Humanism, but none of them accused

the art of the Renaissance of being inimical to Christianity.

Its pagan and materialistic side, not content with restoring antique knowledge and culture to modern humanity, eagerly laid hold of the whole intellectual life of a heathen time, together with its ethical perceptions, its principles based on sensual pleasure and the joy of living; these it sought to bring to life again. This impulse was felt at the very beginning of the fifteenth century; since the middle of the century it had ventured forth even more boldly in Florence, Naples, Rome in the days of Reggio, Valla, Beccadelli, and despite many a repulse had even gained access to the steps of the Papal throne. A literature in substance and essence very much characterized by the Facetiae, by Lorenzo Valla’s Voluptas and Beccadelli’s Hermaphrodituscould not but shock respectable feeling. Florence was the headquarters of this school, and Lorenzo il Magnifico its chief supporter. Scenes that took place there in his day in the streets and squares, the extravagances of the youth of the city lost in sensuality, the writings and pictures offered to the public, would and must seem to earnest-minded Christians a sign of approaching dissolution. A reaction was both natural and justifiable. Giovanni Dominici had introduced it at the beginning of the century, and Fra Antonino of San Marco had supported it, while Archbishop of Florence, with the authority of his blameless life devoted to the service of his fellow-men. And so Cosimo’s foundation became the center and starting-point of a movement destined to attack his own House.

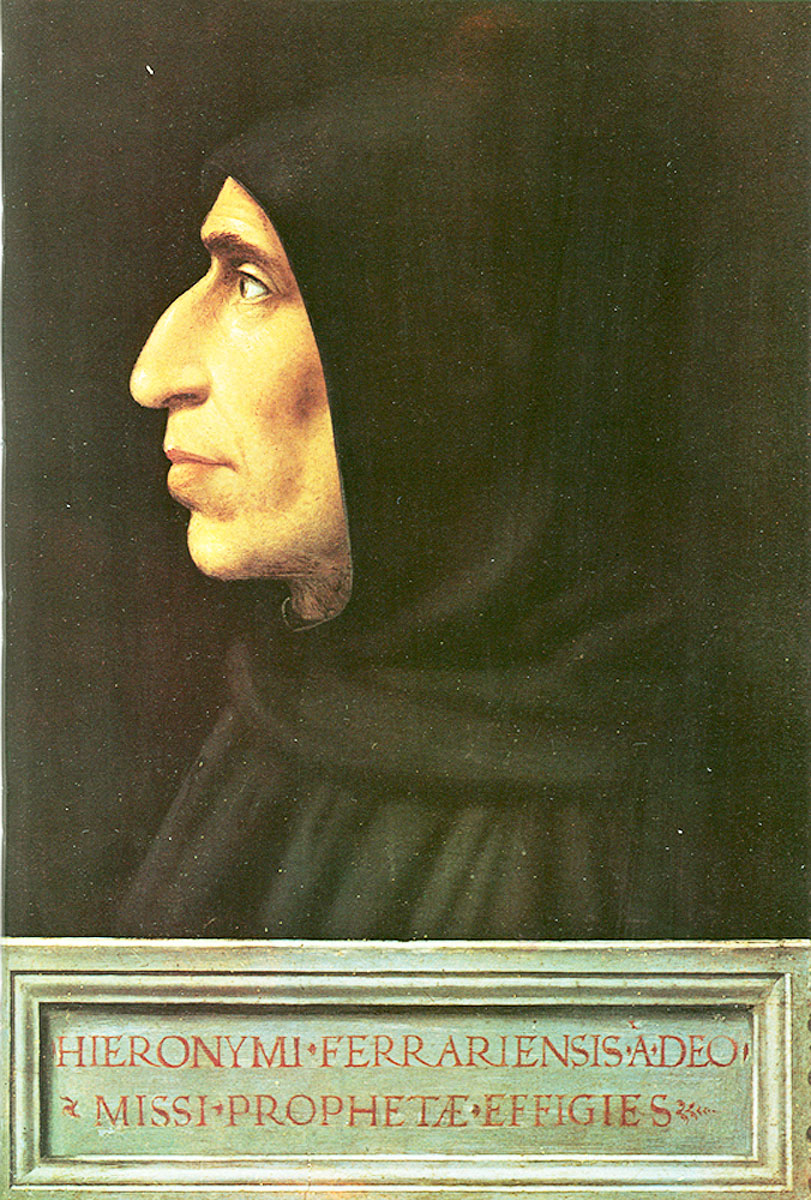

At the head of that movement stood

Fra Girolamo Savonarola. Grief over the degradation of the Church had

driven him into a monastery and now it led him forth to the pulpits of San

Marco and Santa Maria del Fiore. As a youth he had sung his dirge De Ruina Ecclesiae in a canzone since grown

famous; as a man he headed the battle against the immorality and worldliness of

the Curia. He was by no means illiterate, but in the pagan and sensual tendency

of humanist literature and in the voluptuous freedom of art he saw the source

of evil, and in Lorenzo and his sons pernicious patrons of corruption. Zeal

against the immorality of the time, the worldliness of prelates and preachers,

made him overlook the lasting gains that the Renaissance and humanism brought

to humanity. He had no sympathy with this development of culture from the fresh

young life of his own people. He did not understand the Young Italy of his day;

behind this luxuriant growth he could not see the good and fruitful germ, and

here, as in the province of politics, he lost touch with the pulse of national

life. His plan of a theocratic State governed only by Christ, its invisible

Head, was based on momentary enthusiasm and therefore untenable. He was too

deficient in aesthetic sense to be able to rise in inward freedom superior to

discords. Like a dead man amongst the living, he left Italy to bear the clash

of those contradictions which the great mind of Julius II sought, unhappily in

vain, to fuse in one conciliatory scheme.

Such a scheme of conciliation meantime

made its appearance in Florence, not without the co-operation and probably the

encouragement of the Medici. It was connected with the introduction of

Platonism, which since the time of the Council of Florence in 1438 was

represented in that city by enthusiastic and learned men like Bessarion,

and was zealously furthered by Cosimo, the Pater Patriae,

in the Academy which he had founded. From the learned societies started for

these purposes come the first attempts to bring not only Plato’s philosophy but

the whole of classical culture into a close and essential connection with

Christianity. Platonism seemed to them the link which joined Christianity with

antiquity. Bessarion himself had taught the internal relationship of

both principles, and Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola made the

explanation of this theory the work of their lives. If both of them went too

far in their youthful enthusiasm and mysticism, and conceived Christianity

almost as a continuation of Attic philosophy, this was an extravagance which

left untouched the sincerity of their own belief, and from which Marsilio,

when he grew older, attempted to free himself. Giovanni

and Giulio de' Medici, son and nephew of Lorenzo, were both Marsilio’s pupils. Both were destined to wear the

tiara and took a decided part in the scheme for conciliating these contrasts,

which Julius II set forth by means of Raffaelle’s brush.

The victory of the Borgia over the monk of

San Marco was not likely to discourage the skepticand materialistic tendency, whose worst features were incarnate in Alexander VI

and Cesare Borgia. Pietro Pomponazzi furthered

it by his notorious phrase, that a thing might be true in philosophy and yet

false in theology; a formula that spread its poison far and wide. Even then in

Florence a genius was developing, that was to prove the true incarnation of the

pagan Renaissance and modern realism. The flames which closed over Savonarola

had early convinced Niccolò Machiavelli that no reform was to be

looked for from Rome.

Savonarola’s distrust of humanism and his

harsh verdict on the extreme realism of contemporary art were not extinguished

with his life. A few years later we find his thoughts worked out, or rather

extended and distorted in literature. Castellesi (Adriano

di Corneto), formerly secretary to Alexander VI

and created Cardinal May 81, 1503, wrote De ver philosophia ex quattuor doctoribus Ecclesiae,

in direct opposition to the Renaissance and humanism. The author represents

every scientific pursuit, indeed all human intellectual life, as useless for

salvation, and even dangerous. Dialectics, astronomy, geometry, music, and

poetry are but vainglorious folly. Aristotle has nothing to do with Paul, nor

Plato with Peter; all philosophers are damned, their wisdom vain, since it

recognized but a fragment of the truth and marred even this by misuse. They are

the patriarchs of heresy; what are physics, ethics, logic compared with the

Holy Scriptures, whose authority is greater than that of all human

intellect?

The man who wrote these things, and at

whose table Alexander VI contracted his last illness, was no ascetic and no

monkish obscurantist. He was the Pope’s confidant and quite at home in all

those political intrigues which later under Leo X brought ruin upon him. His

book can only be regarded as a blow aimed at Julius II, Alexander’s old enemy,

who now wore the tiara and was preparing to glorify his pontificate by the

highest effort of which Christian art was capable. Providence had granted him

for the execution of his plans three of the greatest minds the world of art has

ever known: never had a monarch three such men as Bramante, Michelangelo,

and Raffaelle at once under his sway. With their help Julius II

resolved to carry out his ideas for the glory of his pontificate and the

exaltation of the Church. What Cardinal Castellesiwanted

was a downright rebellion against the Pope; if he, with his following of

obscurantists, were acknowledged to be in the right, all the plans of the

brilliant and energetic ruler would end in failure, or else be banned as

worldly, and Julius II would lose the glory of having united the greatest and

noblest achievement of art with the memory of his pontificate and the interests

of Catholicism.

The Pope gave Cardinal Castellesi his answer by making the Vatican what it

is. The alteration and enlargement of the palace however passes almost

unnoticed in comparison with the rebuilding of the Basilica of St Peter’s, on

which the Pope was resolved since 1505. With the palace (1504) Bramante seemed

to have set the crown on his many works; but the plans for the new cathedral,

with all the sketches and alternatives which still survive and have been analysed

for us with true critical appreciation, show us Bramante not only in the height

of his creative power, but as perhaps the most universal and gifted mind that

ever used its mastery over architecture. The form of the Greek cross joined

with the vast central cupola might be taken as a fitting symbol for

Catholicism. The arms of the cross, stretched out to the four winds, tell us of

the doctrine of universality; the classical forms preferred by the Latin race,

the elevation with its horizontal lines accentuated throughout, bespeak that

principle of rest and persistence, which is the true heritage of the Catholic

south in contradistinction to the restless striving in search of a visionary

ideal shown in the vertical principle of the north. St Peter’s thus, in the

development planned by Julius, presented the most perfect picture of the

majestic extension of the Church; but the paintings and decorations of the

palace typified the conception of Christianity, humanity led to Christ, the

evolution and great destiny of His Church, and lastly the spiritual empire in

which the Pope, along with the greatest thinkers of his time, beheld the goal

of the Renaissance and the scheme of a new and glorious future, showing

Christianity in its fullest realization.

His own mausoleum gives proof how deeply

Julius II was convinced that the chief part in this development fell to the

Papacy in general, and to himself, Giulian della Rovere, in particular. The instruction which he gave to

Michelangelo to represent him as Moses can bear but one interpretation: that

Julius set himself the mission of leading forth Israel (the Church) from its

state of degradation and showing it, though he could not grant possession, the

Promised Land at least from afar, that blessed land which consists in the

enjoyment of the highest intellectual benefits, and the training and

consecration of all faculties of man’s mind to union with God. He bade

Michelangelo depict on the roof of the Sistine Chapel (1508-9), how after the

fall of our first parents mankind was led from afar towards this high goal;

symbolizing that shepherding of the soul to Christ, which Clement the

Alexandrine had already seen and described. When we see the Sibyls placed among

the Patriarchs and Prophets, we know what this meant in the language of the

theologians and religious philosophers of that time. Not only Judaism, but

also Graeco-Roman paganism, is an antechamber to Christianity; and this

antique culture gave not merely a negative, but also a positive preparation for

Christ. For this reason it could not be considered as a contradiction of the

Christian conception : there was a positive relationship between classical

antiquity and Christianity.

But we see this thought more clearly and

far more wonderfully expressed in the Camera della Segnatura (1509). If we consider what place it was

that Raffaelle was painting, and the character and individuality of

the Pope, we cannot doubt that in these compositions also we are concerned, not

with the subjective inspiration of the artist who executed, but with the Pope’s

own well-considered and clearly formulated scheme. In the last few years it has

been recognized that this scheme is entirely based on the ideas of the universe

represented by the Florentine School. Especially it has been proved that the School

of Athens is drawn after the model

which Marsilio Ficino left of the Accademia, the ancient

assembly of philosophers, while Parnassus has an echo of that bella scuola

the great poets of old times, whom Dante met in the Limbo of the Inferno. The

four pictures of the Camera della Segnatura represent the aspirations of the soul of

man in each of its faculties; the striving of all humanity towards God by means

of aesthetic perception (Parnassus), the exercise of reason in

philosophical enquiry and all scientific research (the School of Athens),

order in Church and State (Gift of Ecclesiastical and Secular Laws), and

finally theology. The whole may be summed up as a pictorial representation of Pico della Mirandola’s celebrated

phrase;

“philosophia veritatem quaerit, theologia invenit, religio possidet”;

and it corresponds with

what Marsilio says in his Academy of Noble Minds when he

characterizes our life’s work as an ascent to the angels and to God.

These compositions are the highest to

which Christian art has attained, and the thoughts which they express are one

of the greatest achievements of the Papacy. The principle elsewhere laid down

is here reaffirmed: that the reception of the true Renaissance into the circle

of ecclesiastical thought points to a widening of the limited medieval

conception into universality, and indicates a transition to entire and actual

Catholicity, like the great step taken by Paul, when he turned to the Gentiles

and released the community from the limits of Judaistic teaching.

This expansion and elevation of the

intellectual sphere is the most glorious achievement of Julius II and of the

Papacy at the beginning of modern times. It must not only be remembered, but

placed in the most prominent position, when history sums up this chapter in

human development. Since Luther’s time it has been the custom to consider the

Papacy of the Renaissance almost exclusively as viewed by theologians who

emphasized only moral defects in the representatives of this institution and

the neglect of ecclesiastical reform. Certainly these are important

considerations, and our further deductions will prove that we do not neglect

them nor underestimate their immense significance for the life of the Church

and Catholic unity. But from this standpoint we can never succeed in grasping

the situation. Ranke in his Weltgeschichte could

write the history of the first hundred years of the Roman Empire, without

giving one word to all the scandalous tales that Suetonius records. The course

of universal history and the importance of the Empire for the wide provinces of

the Roman world were little influenced by them. Similarly, private faults of

the Renaissance Popes were fateful for the moral life of the Church, but the

question of what the Papacy was and meant for these times, is not summed up or

determined by them. It is the right of these Popes to be judged by the better

and happier sides of their government; the historian who portrays them should

not be less skilful than the great masters of the Renaissance, who in their

portraits of the celebrities of their time contrived to bring out the sitters'

best and most characteristic qualities. Luther was not touched in the least

degree by the artistic development of his time; brought up amid the peasant

life of Saxony and Thuringia he had no conception of the whole world that lay

between Dante and Michelangelo, and could not see that the eminence of the

Papacy consisted at that time in its leadership of Europe in the province of

art. But to deny this now would be injustice to the past.

The Medici had not stood aloof from this

evolution, which reached its highest point under Julius II. Search has been

made for the bridge by means of which the ideas of Marsilio and his

fellow thinkers were brought from Florence to Rome. But there is no real need

to guess at definite personages. Hundreds of correspondents had long since made

all Italy familiar with this school of thought. Among those who frequented the

Court of Rome, Castiglione, Bibbiena, Sadoleto, Inghirami,

and Beroaldus had been educated in the

spirit of Marsilio. His old friend and correspondent Raffaelle Riario was now, as Cardinal of San Giorgio and the

Pope’s cousin, one of the most influential personages in the Vatican. But

before all we must remember Giovanni de' Medici and his cousin Giulio, the

future Popes. They were Marsilio’s pupils,

and after the banishment of their family he remained their friend and

corresponded with them, regarding them as the true heirs of Lorenzo’s

spirit; Raffaelle has represented the older cousin Giovanni standing

near Julius II in the Bestowed of Spiritual Laws.

It was a kingdom of intellectual unity,

which the brush of the greatest of painters was commissioned to paint on the

walls of the Camera della Segnatura; the same idea which Julius caused to be

proclaimed in 1512, in the opening speech

of Aegidius of Viterbo at the Lateran Council, referring to

the classical proverb: “simplex sermo veritatis”. The world of the beautiful, of reason and

science, of political and social order, had its place appointed in the kingdom

of God upon earth. A limit was set to the neglect of secular efforts to explore

nature and history, to the disregard of poetry and art, and its rights were

granted to healthy human reason organized in the State; Gratiae et Musae a

Deo sunt atque ad Deum referendae, as Marsilio had said.

The programme laid down by

Julius II, had it been carried out, might have saved Italy and preserved the

Catholic principle, when imperilled in the North. The task was to bring modern

culture into harmony with Christianity, to unite the work of the Renaissance,

so far as it was really sound and progressive, with ecclesiastical practice and

tradition into one harmonious whole. The recognition of the rights of

intellectual activity, of the ideal creations of human fancy, and of the

conception of the State, were the basis for this union. It remains to be shown

why the attempt proved fruitless.

The reign of Julius II was one long

struggle. The sword never left his grasp, which was more used to the handling

of weapons than of Holy Writ. On the whole, the Pope might at the close of his

pontificate be contented with the success of his politics. He had driven the

French from Italy, and the retreat of Louis XII from Lombardy opened the Gates

of Florence once more to the Medici. The Council of Pisa, for which France had

used her influence, had come to naught, and its remnant was scattered before

the anger of the victorious Pontiff. And as he had freed Italy from the

ascendancy of France so he now hoped to throw off that of Spain. It may be a

legend that as he was dying he murmured “Fuori i barbari”, but these

words certainly were the expression of his political thought. But this second

task was not within his power. On the 3rd of May, 1512, he had opened the

Lateran Council to counteract that of Pisa. At first none of the great Powers

was represented there; 15 Cardinals, 14 Patriarchs, 10 Archbishops, and 57

Bishops, all of them Italians, with a few heads of monastic Orders, formed this

assembly, which was called the Fifth General Lateran Council. Neither Julius

nor Leo was ever able to convince the world that this was an ecumenical

assembly of Christendom. Julius died in the night of February 20-1,

1513. Guicciardini calls him a ruler unsurpassed in power and

endurance, but violent and without moderation. Elsewhere he says that he had

nothing of a priest but vesture and title. The dialogue, Julius Exclusus, attributed sometimes to Hütten, sometimes to Erasmus, and perhaps written

by Fausto Andrelini, is the harshest

condemnation of the Pope and his reign. But at bottom the pamphlet is

exceedingly one-sided and the outcome of French party-spirit. Although in many

cases the author speaks the truth, and for instance even at that time (1513)

unfortunately was able to put such words into the Pope’s mouth as

“Nos Ecclesiam vocamus sacras aedes, sacerdotes, et praecipue Curiam Romanam,

me imprimis, qui caput sum Ecclesiae”,

yet this is more a common trait of the

office than a characteristic of Julius II. It almost raises a smile to read

in Pallavicino, that on his death-bed the

magnanimity of Julius was only equalled by his piety, and that, although he had

not possessed every priestly perfection, perhaps because of his natural

inclinations, or because of the age, which had not yet been disciplined by the

Council of Trent, yet his greatest mistake had been made with the best

intention and proved disastrous by a mere chance, when, as Head of the Church,

and at the same time as a mighty Prince, he undertook a work that for these

very reasons exceeded the means of his treasury, the building of St Peter’s. We

see that neither his enemies nor his apologists had the least idea wherein

Julius’ true greatness consisted. With such divided opinions it cannot surprise

us that contemporaries and coming generations alike found it difficult to form

a reasoned and final judgment of the pontificate which immediately

followed.

Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici came

forth from the conclave summoned on March 4, 1513, as Pope Leo X.

Since Piero had been drowned on the 9th of December, 1503, Giovanni

had become the head of the House of Medici. He was only 38 years of age at the

election, to which he had had himself conveyed in a litter from Florence to

Rome, suffering from fistula. The jest on his short-sightedness,

“multi coeci Cardinales creavere caecum decimum Leonem”,

by no means expressed public opinion,

which rejoiced at his accession. The Possesso,

which took place on April 11th, with the great procession to the Lateran, was

the most brilliant spectacle of its kind that Christian Rome had ever

witnessed. What was expected of Leo was proclaimed in the inscription

which Agostino Chigi had attached to

his house for the occasion:

“Olim habuit Cypris sua tempora, tempora Mavors

Olim habuit,ma nunc tempora Pallas habet”.

But other expectations were not wanting

and a certain goldsmith gave voice to them in the line :

“Mars fuit; est Pallas; Cypria semper ero”.

To Leo X the century owed its name.

The Saecula Leonis have been called the Saecula Aurea,

and his reign has been compared with that of Augustus. Erasmus, who saw him in

Rome in 1507 and 1509, praises his kindness and humanity, his magnanimity and

his learning, the indescribable charm of his speech, his love of peace and of

the fine arts, which cause no sighs, no tears; he places him as high above all

his predecessors as Peter’s Chair is above all thrones in the world. Pallavicino says of Leo that he was well-known for his

kindness of heart, learned in all sciences, and had passed his youth in the

greatest innocence. That as Pope he let himself be blinded by appearances,

which often confuse the good with the great, and chose rather the applause of

the crowd than the prosperity of the nation, and thus was tempted to exercise

too magnificent a generosity. Such expressions from one who is the

unconditional apologist of all the Popes cannot make much impression, but it is

noticeable that even Sarpi says: “Leo,

noble by birth and education, brought many aptitudes to the Papacy, especially

a remarkable knowledge of classical literature, humanity, kindness, the

greatest liberality, an avowed intention of supporting artists and learned men,

who for many years had enjoyed no such favour in the Holy See. He would have

made an ideal Pope had he added to these qualities some knowledge of the things

of religion, and a little more inclination to piety, both of them things for

which he cared little”.

The favourable opinion entertained of Leo

X by his contemporaries long held the field in history. His reign has been

regarded as at once the zenith and cause of the greatest period of the

Renaissance. His wide liberality, his unfeigned enthusiasm for the creations of

genius, his unprejudiced taste for all that beautifies humanity, and his

sympathy for all the culture of his time have been the theme of a traditional

chorus of laudation. More recent criticism has recognized in the reign of Leo a

period of incipient decline, and has traced that decline to the follies and

frailties of the Pontiff.

With regard to the political methods of

Leo some difference of opinion may still be entertained. Some have seen in him

the single-minded and unscrupulous friend of Medicean Florence,

prepared to sacrifice alike the interests of the Church and of the Papacy to

the advancement of his family. To others he is the clear-sighted statesman who,

perceiving the future changes and difficulties of the Church, sought for the

Papacy the firm support of a hereditary alliance.

Truth may lie midway between these two

opinions. If we view Leo as a man, similar doubts encounter us. Paramount in

his character were his gentleness and cheerfulness, his good-nature, his

indulgence both for himself and others, his love of peace and hatred of war.

But these amiable qualities were coupled with an insincerity and a love of

tortuous ways which grew to be a second nature. Nor must we overlook the fact

that Leo’s policy of peace was a mere illusion; his hopes and intentions were

quite frustrated by the actual course of affairs. On his personal character the

great blot must rest that he passed his life in intellectual self-indulgence

and took his pleasure in hunting and gaming, while the Teutonic North was

bursting the bonds of reverence and authority which bound Europe to Rome. Even

for the restoration of the rule of the Medici in Florence the Medicean Popes made only futile

attempts. Cosimo I was the first to accomplish it. Leo had absorbed

the culture of his time, but he did not possess the ability to look beyond that

time. A diplomatist rather than a statesman, his creations were only the feats

of a political virtuoso, who sacrificed the future in order to control the

present.

Even the greatness of the Maecenas

crumbles before recent criticism. The zenith of Renaissance culture falls in

the age of Julius II.

Ariosto’s light verses, Bibbiena’s prurient, La Calandria,

the paintings in the bath-room of the Vatican, the rejection of the Dante

monument planned by Michelangelo, the misapplication of funds collected for the

Crusade to purposes of mere dynastic interest, Leo’s political double-dealing,

which disordered all the affairs of Italy, and indeed of Christendom; all this

must shake our faith in him as protector of the good and beautiful in art. His

portrait by Raffaelle, with its intelligent but cold and sinister face,

may assist to destroy any illusions which we may have had about his

personality.

The harshness and violence of Leo’s

greater predecessor, Julius, brought down on him the hatred of his

contemporaries and won for his successor an immense popularity without further

effort. The spiritual heir of Lorenzo il Magnifico, Rome and all

Italy acclaimed

Leo pacis restauratorem, felicissimum litteratorum amatorem;

and Erasmus proclaimed to the world that

“an age, worse than that of iron, was suddenly transformed into one of gold”.

And there can be no doubt that when Leo X was greeted on his accession, like

Titus, as the deliciae generis humani he made every disposition to respond to

these expectations and prove himself the most liberal of patrons. The Pope,

however, did not long keep this resolution; his weakness of purpose, his

inclination to luxury, enjoyment, and pleasures, soon quenched his sense of the

gravity of life and all his higher perceptions; so that a swift and sad decline

followed on the first promise.

On Leo’s accession he found a number of

great public buildings in progress which had been begun under his great

predecessor but were still unfinished. Among them were the colossal palace

planned by Bramante in the Via Giulia, St Peter’s also began by him, and his

work of joining the Vatican with the Belvedere, besides

the loggie and buildings in Loreto. Leo, who was not in the least

affected by the passion of building -il mal di pietra-

did not carry on these undertakings. He even hindered Michelangelo from

finishing the tomb of Julius II, so little reverence had he for the memory of

the Pope to whom he owed his own position. Only the loggie were

finished, since they could not remain as Bramante had left them. Even after

Bramante’s death there was no lack of architects who could have finished St

Peter’s. Besides Raffaelle, who succeeded to his post as architect,

Sangallo and Sansovino, Peruzzi and Giuliano Leno waited in vain for

commissions. While Raffaelle in a letter relates that the Pope had

set aside 60,000 ducats a year for the continuation of the building, and talked

to Fra Giocondo about it every day, he

might soon after have told how Leo went no further, but stopped at the good

intention. As a matter of fact work almost entirely ceased because the money

was not forthcoming. There is therefore no reason to

reproach Raffaelle with the delay in building. On the contrary, by

not pressing Leo to an energetic prosecution of the work, Raffaelle probably

did the building the greatest service; since the Pope’s mind was full of plans,

for which Bramante’s great ideas would have been entirely forsaken. No one

could see more clearly than Raffaelle the harm which would have thus

resulted.

Leo X not only neglected the undertakings

of his predecessor; he created nothing new in the way of monumental buildings

beyond the portico of the Navicella, and a few

pieces of restoration in San Cosimate and

St John Lateran. The work he had done beyond the walls in his villas and hunting

lodges (in Magliana, at Palo, Montalto,

and Montefiascone) served only the purposes of

his pleasure. Of the more important palaces built in the city two fall to the

account of his relatives Lorenzo and Giulio, that of the Lanti (Piazza de’ Caprettari)

and the beautiful Villa Madama on the Monte Mario, begun

by Raffaelle, Giulio Romano, and Giovanni da Udine, but never

finished. Cardinal Giulio de' Medici it was who carried on the

building of the Sacristy in San Lorenzo at Florence, in which Michelangelo was

to place the tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo; but the façade which the Pope had

planned for the church was never executed. Nor were any of the palaces built by

dignitaries of the Church under Leo X of importance, with the exceptions of a

part of the Palazzo Farnese and the Palazzo di Venezia. Even the palaces

and dwelling-houses built by Andrea Sansovino, Sangallo,

and Raffaelle will not bear comparison with the creations of the

previous pontificate, nor with the later parts of the Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola.

Sculpture had flourished under Pius II in

the days when Mino of Fiesole and Paolo Romano were in Rome; it could point to

very honourable achievements under Alexander VI and Julius II

(Andrea Sansovino’s monuments of the Cardinals Basso and Sforza in

Santa Maria del Popolo); but this art also

declined under Leo X; for the work done by Andrea Sansovino in Loreto

under his orders falls in the time of Clement VII, after whose death in 1534

the greater part of the plastic ornament of the Santa Casa was executed. The

cardinals and prelates who died in Rome between 1513 and 1521 received only

poor and insignificant monuments, and Leo’s colossal statue in Ara Coeli, the work of Domenico d’Arnio,

can only be called a soulless monstrosity.

Painting flourished more under this Pope,

who certainly was a faithful patron and friend to Raffaelle. The

protection he showed to this great master is and always will be Leo’s best and

noblest title to fame. But he allowed Leonardo to go to France, when after

Bramante’s death he might easily have won him, had he bestowed on him the post

of piombatore apostolico ,

instead of giving it to his maître de plaisirs, the shallow-minded

Fra Mariano (sannio cucullatus). He allowed Michelangelo to return to

Florence, and, though he loaded Raffaelle with honours, it is a fact

that he was five years behindhand with the payment of his salary as architect

of St Peter’s. A letter of Messer Baldassare Tunni da Pescia turns on the ridiculous investiture of the

jester Mariano with the tonaca of

Bramante, performed by the Pope himself when Bramante was scarce cold in his

grave. This leaves a most painful impression, and makes it very doubtful

whether Leo ever took his patronage of the arts very seriously. In the same way

his love of peace is shown in a very strange light during the latter half of

his reign by the high-handed campaign against the Duke

of Urbino (1516); the menace to Ferrara (1519); the crafty enticing

of Giampaolo Baglione, Lord of Perugia, to

Rome and his murder despite the safe-conduct promised him; the war

against Ludovico Freducci, Lord

of Fermo; the annexation of the towns and fortresses in the province of

Ancona; the attempt on the life of the Duke of Ferrara; the betrayal of Francis

I and the league with Charles V in 1521. The senseless extravagance of the

Court, the constant succession of very mundane festivals, hunting-parties, and

other amusements, left Leo in continual embarrassment for money and led him

into debt not only to all the bankers but to his own officials. They even drove

him to unworthy extortion, such as followed on the conspiracy of

Cardinal Petrucci and the pardon granted to his accomplices, or that

which was his motive for the creation of thirty-one cardinals in a single day.

All this taken together brings us to the

conclusion that Leo’s one real merit was his patronage of Raffaelle.

Despite the noble and generous way in which his reign began the Pope soon fell

into an effeminate life of self-indulgence spent among players and buffoons, a

life rich in undignified farce and offensive jests, but poor in every kind of

positive achievement. The Pope laughed, hunted, and gambled; he enjoyed the

papacy. Had he not said to his brother Giuliano on his accession:

“Godiamoci il papato poichè Dio ci l’ ha dato?”.

Though he himself has not been accused of

sensual excesses the moral sense of the Pope could not be delicate when he

found fit to amuse himself with indecent comedies like La Calandria,

and on April 30, 1518, attended the wedding of Agostino Chigi with his concubine of many years’ standing,

himself placing the ring on the hand of the bride, already mother of a large

family.

Nor can Leo’s reign, apart from his own

share in it, be regarded as the best period of the Renaissance. The great

masters had done their best work before 1513. Bramante died at the beginning of

Leo’s pontificate, Michelangelo had painted the Sistine Chapel from 1508 to

1512, Leonardo the Cena in 1496, Raffaelle the Stanza della Segnatura, 1508-11.

The later Stanze are far inferior to

that masterpiece; the work of his pupils comes more to the fore in the

execution of the paintings. And in his own work, as also in that of

Michelangelo, the germ of decadence is already visible, and a slight tendency

to barocco style is to be seen in

both. The autumn wind is blowing, and the first leaves begin to fall.

The truth results that the zenith of

Renaissance art falls in the time between 1496 and 1512, during which the Last

Supper, the roof of the Sistine Chapel, and the Stanza della Segnatura were

painted, and Bramante’s plans for St Peter’s were drawn up. We can even mark a

narrower limit, and say that the four wall-paintings of the Stanza della Segnatura mark

the point at which medieval and modern thought touch one another; the narrow

medieval world ceases, the modern world stands before us developed in all its

fullness and freedom. One may indeed doubt whether all the meaning of this

contrast was quite clear to the mind of Julius II; but after all that is a

matter of secondary importance. For it is not the individual who decides in

such matters; without being aware of it he is borne on by his time and must

execute the task that history has laid upon him. Great men of all times are

those who have understood the cry from the inmost heart of a whole nation or

generation and, consciously or unconsciously, have accomplished what the hour

demanded.

It has been in like manner represented

that literature passed through a golden age under Leo X; but considerable deductions

must be made from the undiscriminating eulogies of earlier writers.

Erasmus has reflected in his letters the

great impression made by Rome, the true seat and home of all Latin culture.

Well might Cardinal Raffaelle Riariowrite

to him: “Everyone who has a name in science throngs hither. Each has a

fatherland of his own, but Rome is a common fatherland, a foster-mother, and a

comforter to all men of learning”. It is long since these words were

written-far too long for the honour of Catholicism and of the Papacy. But at

that time, under Julius II, they were really true. A circle of highly cultured

cardinals and nobles, Riario, Grimani, Adriano di Corneto,

Farnese, Giovanni de’ Medici himself in his beautiful Palazzo Madama, his

brother Giuliano il Magnifico, and his cousin Giulio,

afterwards Clement VII, gathered poets and learned men about them, that dottacompagnia of

which Ariosto spoke; to them they opened their libraries and collections. Clubs

were formed which met at the houses of Angelo Colocci,

Alberto Rio di Carpi, Goritz, or Savoja. The poets and pamphleteers, to whom Arsilli dedicated his poem De Poetis Urbanis, gave

vent to their wit on Pasquino or

on Sansovino’s statue in Sant’ Agostino. They met in the

salons of the beautiful Imperia, in the banks described by Bandello, among

them Beroaldo the younger, who sang the

praises of that most celebrated of modern courtesans; Fedro Inghirami, the friend of Erasmus and Raffaelle; Colocci, and even the serious Sadoleto.

It is characteristic of this time, which placed wit and beauty above morals,

that when Imperia died at the age of twenty-six she received an honourable

burial in the chapel of San Gregorio, and her epitaph praised the

“Cortisana Romana quae, digna tanto nomine, rarae inter homines formae specimen dedit”. And although women no longer played so

prominent a part at the papal Court as they had done under Innocent VIII and

Alexander VI, yet, as Bibbiena wrote to

Giuliano de’ Medici, the arrival of noble ladies was extremely welcome as

bringing with it something of a corte de’ donne.

The activity of the greater number of literary men and wits, whose names have most contributed to the glory of Leo’s pontificate, dates back to Giulio’s time; so for instance Molza, Vida, Giovio, Valeriano, whose dialogue De Infelicitate Litteratorum tells of the fate of many of his friends, Porzio, Cappella, Bembo, who as Latinist was the chief representative of the cult of Cicero, and as a writer in the vulgar tongue gave Italy her prose, and Sadoleto, who chronicled the discovery of the Laocoon group. Pontano too and Sannazaro, Fracastan and Navagero had already done their best work. Nothing could be more unjust than to deny

that Giovanni de’ Medici himself had a highly cultured mind and an excellent

knowledge of literature. It may be that Lorenzo had destined him for the Papacy

from his birth; certainly he gave him the most liberal education. He gave

him Poliziano, Marsilio, Pico della Mirandola,

Johannes Argyropoulos, Gentile d’ Arezzo for his

teachers and constant companions, and, to teach him Greek, Demetrius Chalcondylas and Petrus Aegineta.

Afterwards Bernardo di Dovizi (Bibbiena) was his best known tutor. In belles lettres Giovanni had made an attempt with Greek

verses, none of which have survived. Of his Latin poems the only examples

handed down to us are the hendecasyllables on the statue

of Lucrezia and an elegant epigram, written during his pontificate,

on the death of Celso Mellini, well known

for his lawsuit in 1519 and his tragic death by drowning.

Nor can it be denied that the opening

years of this pontificate were of great promise, and seemed to announce a fresh

impetus, or, to speak more exactly, the successful continuation of what had

long since begun. Amongst the men whom the young Pope gathered round him were

many of excellent understanding and character, such as the

Milanese Agostino Trivulzio, who later on

was to do Clement signal service, Alessandro Cesarini,

Andrea della Valle, Paolo Emilio Cesi, Baldassare Turini,Tommaso de Vio, Lorenzo Campeggi, the

noble Ludovico di Canossa, from Verona, most of whom wore the

cardinal’s hat. Bembo and Sadoleto were

the chief ornaments of his literary circle; to them was added the celebrated

Greek John Lascaris, once under the protection

of Bessarion, then of Lorenzo il Magnifico and Louis XII,

in France the teacher of Budaeus, in Venice of

Erasmus. Leo X on his accession at once summoned him to Rome, and on his

account founded a school of Greek in the palace of the Cardinal

of Sion on Monte Cavallo. Lascaris’

pupil, Marcus Musurus, was also summoned from

Venice in 1516 to assist in this school. At the same time the Pope

commissioned Beroaldus to publish the

newly-discovered writings of Tacitus. A measure, which might have proved of the

utmost importance, was the foundation of the university of Rome by the

Bull Dum Suavissimos of

November 4, 1513. This was a revival and confirmation of an already existing

Academy, in which under Alexander VI and Julius II able men such as Beroaldo the younger, Fedr, Casali, and Pio had taught, and to which now

others were summoned, among them Agostino Nifo, Botticella, Cristoforo Aretino, Chalcondylas, Parrasio,

and others, Vigerio and Tommaso de Vio(Cardinal of Gaeta) also on theology, and

Giovanni Gozzadini on

law. Petrus Sabinus, Antonio Fabro of Amiterno, and Raffaelle Brandolini are

mentioned among the lecturers, and even a Professor of Hebrew, Agacius Guidocerius, was

appointed. Cardinal Raffaelle Riario acted

as Chancellor. The list of the professors given by Renazzi numbers

88: 11 in canon law, 20 in law, 15 in medicine, and 5 in philosophy. It was

another merit of Leo’s that he established a Greek printing-press, which

printed several books in 1517 and 1518. Chigi had

some years before set up a Greek press in his palace, from which came the first

Greek book printed in Rome, a Pindar, in 1515. The Pope himself kept up his

interest in Greek studies, and retained as custodian of his private library one

of the best judges of the Greek idiom, Guarino di Favera, who published the first Thesaurus

linguae Graecae< in 1496, and whom he

nominated Bishop of Novara.

Unfortunately these excellent beginnings

were for the most part not carried on. It was not Leo’s fault, but his

misfortune, that many of the most gifted men he had summoned were soon removed

by death. But we cannot acquit him of having ceded Lascaris like

Leonardo to France in 1518, and allowed Bembo to return discontented

to Padua; he did not secure Marcantonio Flaminio,

and held Sadoleto at a distance for a very

long time. The continual dearth of money in the papal treasury was no doubt the

chief cause of this change of policy. Even before 1517 the salaries of the

professors could not be paid, and their number had to be diminished. And this

was the necessary consequence of Leo’s ridiculous prodigality on his pleasures

and his Court. Well might a Fra Mariano exclaim “beviamo

al babbo santo, che ogni altra cosa è burla”. Serious and respectable men left him and a

pack of “pazzi, buffonie simil sorta di piacevoli” remained in the Pope’s audience chambers,

with whom he, the Pope himself, gamed and jested day after day “cum risu et hilaritate”.

Such were the people that he now raised to honour and position; what

money he had he spent for their carousals. No wonder that this vermin flattered

his vanity and sounded his praises as “Leo Deus noster”.

But beside this we must remember, that, as is universally admitted, Leo was

extremely generous to the poor. The anonymous author of the Vita Leonis X, reprinted

in Roscoe’s Life, gives express evidence as to this, “egentes pietate ac liberalitate est prosecutes”,

and adds that, according to accounts which are, however, not very well

attested, he supported needy and deserving ecclesiastics of other nationalities.

But he too remarks, that Leo’s chief, if not his only, anxiety was to lead a

pleasant and untroubled life; in consequence of which he spent his days at

music and play, and left the business of government entirely in the hands of

his cousin Giulio, who was better fitted for the task and an industrious

worker. Unfortunately he admitted not only buffoons to his games of cards, but

also corrupt men like Pietro Aretino, who lived on the Pope’s

generosity as early as 1520, and in return extolled him as the pattern of all

pontiffs. The appointment of the German Jew Giammaria as

Castellan and Count of Verrucchio was even

in Rome an unusual reward for skilled performance on the lute, and even for the

third successor of Alexander VI it was venturesome to let the poet Querno, attired as Venus and supported by two Cupids,

declaim verses to him at the Cosmalia in

1519. We have already mentioned the scandalous carnival of that year, and the

theatre for which Raffaelle was forced to paint the scenery. A year

later an unknown savant, under the mask of Pasquino,

complained of the sad state of the sciences in Rome, of the exile of the Muses,

and the starvation of professors and literary men.

From all this data the conclusion has been

drawn that Leo X was by no means a Maecenas of the fine arts and sciences; that

the high enthusiasm for them shown in his letters, as edited

by Bembo and Sadoleto, betrays more of

the thoughts of his clever secretary than his own ideas; and that his literary

dilettantism, was lacking in all artistic perception, and all delicate

cultivation of taste. Leo has been thought to owe his undeserved fame to the

circumstance that he was the son of Lorenzo, and that his accession seemed at

the time destined to put an end to the sad confusions and wars of the last

decades. Moreover, throughout the long pontificate of Clement VII, and equally

under the pressure of the ecclesiastical reaction in the time of Paul IV, no

allusion was allowed to the wrongdoing of this Leonine period; till at last the

real circumstances were so far forgotten, that the fine flower of art and

literature in the first twenty years of the sixteenth century was attributed to

the Medicean Pope.

But there are points to be noted on the

other side. Even if we discount much of the praise which Poliziano lavishes on his pupil in deference to his

father, we cannot question the conspicuous talent of Giovanni de’ Medici, the

exceptionally careful literary education which he had enjoyed, and his liberal

and wise conduct during his cardinalship. We must also esteem it to his credit

that as Pope he continued to be the friend of Raffaelle, and that in Rome

and Italy at least he did not oppress freedom of conscience, nor sacrifice the

free and noble character of the best of the Renaissance. Nor can it be

overlooked that his pontificate made an excellent beginning, though certainly

the decline soon set in; the Pontiff's good qualities became less apparent, his

faults more conspicuous, and events proved that, as in so many other instances,

the man's intrinsic merit was not great enough to bear his exaltation to the

highest dignity of Christendom without injury to his personality.

Such a change in outward position,

promotion to an absolute sway not inherited, intercourse with a host of

flatterers and servants who idolized him (there were 2000 dependents at Leo’s

Court), all this is almost certain to be fatal to the character of the man to

whose lot it falls. Seldom does the possessor of the highest dignity find this

enormous burden a source and means of spiritual illumination and moral

advancement. Mediocre natures soon develop an immovable obstinacy, the despair

of any reasonable adviser, and which is none the more tolerable for having

received the varnish of a piety that worships itself. Talented natures too

easily fall victims to megalomania, and by extravagant and ill-considered

projects and undertakings drag their age with them into an abyss of ruin. Weak

and sensual natures give themselves up to enjoyment, and consider the highest

power merely as a license to make merry. Leo was not a coarse voluptuary like

Alexander VI, but he certainly was an intellectual Epicurean such as has seldom

been known. Extremes should be avoided in forming a judgment of the pontificate

and character of this prince. Not the objective historian, but the flattering

politician, spoke in Erasmus when he lauded the three great benefits which Leo

had conferred on humanity: the restoration of peace, of the sciences, and of

the fear of God. It was a groundless suspicion that overshot the mark, when

Martin Luther accused Leo of disbelief in the immortality of the soul; and John

Bale (1574) spread abroad the supposed remark of the Pope to Bembo: “All

ages can testify enough, how profitable that fable of Christ has been to us and

our compagnie”. Hundreds of writers have copied this from Bale without

verification. Much of Leo’s character can be explained by the fact that he was

a true son of the South, the personification of the soft Florentine

temperament. This accounts for his childish joy in the highest honour of

Christendom, “Questo mi

da piacere, che la mia tiara!” The words of the office which he was

reading, when five days before his death news was brought to him of the taking

of Milan by his troops, may well serve as motto for this reign, lacking not

sunshine and glory, but all serious success and all power:

“Ut sine timore de manu inimicorum nostrorum liberati serviamus illi”. This pontificate truly was, as Gregorovius has described it, a revelry of culture, which Ariosto accompanied with a poetic obbligato in his many-colored Orlando. This poem was in truth “the image of Italy revelling in sensual and intellectual luxury, the ravishing, seductive, musical, and picturesque creation of decadence, just as Dante’s poem had been the mirror of the manly power of the nation”.

On December 27, 1521, a Conclave

assembled, which closed on January 9, 1522, by the election of the Bishop

of Tortosa as Adrian VI. He was born at

Utrecht in 1459 and when a professor in Louvain was chosen by the Emperor

Maximilian to be tutor to his grandson Charles. Afterwards he was sent as

ambassador to Ferdinand the Catholic, who bestowed on him the Bishopric

of Tortosa; Leo X made him Cardinal in 1517.

This Conclave, attended by thirty-nine cardinals, offered a spectacle of the

most disgraceful party struggles, but mustered enough unanimity to propose to

the possible candidates a capitulation, by the terms of which the towns of the

Papal States were divided amongst the members of the Conclave, and hardly

anything of the temporal power was left to the Pope. The Cardinals de’ Medici

and Cajetan (de Vio) rescued the

assembly from this confusion of opinions and unruly passions by proposing an

absent candidate. None of the factions had thought of Adrian Dedel; the astonished populace heaped scorn and epigrams on

the Cardinals and their choice. Adrian, who was acting as Charles’ vicegerent

in Spain at the time of his election, could not take up his residence at Rome

till August 29; it then looked, as Castiglione says, like a plundered abbey;

the Curia was ruined and poverty-stricken, half their number had fled before

the prevailing pestilence. The simple-minded old man had brought his aged

housekeeper with him from the Netherlands; he was contented with few servants

and spent but a ducat a day for maintenance. He would have preferred to live in

some simple villa with a garden; in the Vatican among the remains of heathen

antiquity he seemed to himself to be rather a successor of Constantine than of

St Peter. His plan of action included the restoration of peace to Italy and

Europe, a protective war against the invading Turks, the reform of the Curia

and the Church, and the establishment of peace in the German Church. Not one of

these tasks was he able to fulfil; he was destined only to show his good

intentions.

We shall deal presently with his attempts

at reformation, which have for all time made him worthy of admiration and his

short pontificate memorable. He was not lacking in good intentions to make Rome

once more the center of intellectual life; but

Reuchlin had lately died; Erasmus, to whom the Pope had written on December 1,

1522, preferred to remain in Germany; Sadoleto went

to Carpentras; and Bembo, who thought

Adrian’s pontificate even more unfortunate than Leo’s death, stayed quietly in

northern Italy. Evidently no one had confidence in the permanency of a state of

things which could not but appear abnormal to everybody. And indeed, the

silent, pedantic Dutchman, with his cold nature, his ignorance of Italian, his

handful of servants, “Flemings stupid as a stone”, was the greatest possible

contrast to everything that the refinement of Italian culture and the

well-justified element of Latin grace and charm demanded of a prince. The

Italians would have put up for a year or two at least with an austere and pious

Pope, if his piety had been blended with something of poetry and grace; but

this Dutch saint was utterly incomprehensible to them. And in truth this was

not entirely their fault. As Girolamo Negri wrote, one really

could apply to him Cicero’s remark about Cato : “he behaves as if he had to do

with Plato’s Republic instead of the scum of the earth that Romulus collected”.

And it must have been unbearable for the Romans that the new Pope should have

as little comprehension for all the great art of the Renaissance as for

classical antiquity. He wanted to throw Pasquino into

the Tiber because the jests pasted on the statue irritated him; at the sight of

the Laocoon he turned away with the words, “These are heathen idols”.

He closed the Belvedere, and even a man like Negri was seriously

afraid that someday the Pope would follow the supposed example of Gregory, and

have all the heathen statues broken and used as building stones for St Peter’s.

In a word, despite the best intentions,

despite clear insight, Adrian was not adequate to his task. The moment demanded

a Pope who could reconcile and unite all the great and valuable elements of the

Italian Renaissance, the ripened fruit of the modern thought sprung from Dante

and Petrarch, with the conceptions and conscience of the Germanic world. Both

the German professors who now posed as leaders of Christendom, Adrian Dedel and Martin Luther, were lacking in the historic

and aesthetic culture which would have enabled them to understand the value of

Roman civilization. Erasmus saw further than either of them, but the

discriminating critic lacked the unselfish nobility of soul and the impulse

which can only be given by a powerful religious excitement, an unswerving

conviction, the firm faith in a personal mission confided by Providence. He

too, despite his immense erudition, his deep insight, left the world to its own

devices when it required a mediator; for a gentle and negative criticism of

human folly is, taken by itself, of little value.

Adrian could neither gain the mastery over

Luther’s Reformation, nor succeed in reforming even the Roman Curia, to say

nothing of the whole Church. The luxurious Cardinals went on with their

pleasant life; when he came to die they demanded his money and treated him, as

the Duke of Sessa expressed it, like a criminal on the rack. The

threat of war between France and the German Empire lay all the while like an

incubus on his pontificate. With heavy heart the most peace-loving of all the

Popes, reminded by Francis I of the days of Philip the Fair, was at last

obliged to enter into a treaty with England and Germany. Adrian survived to see

war break out in Lombardy; he died on the day when the French crossed the

Ticino, September 14, 1523. Giovio and Guicciardini relate

that some wag wrote on the door of his physician, “To the deliverer of the

Fatherland, from the senate and people of Rome”. Little as the people were

delighted with the pontificate of this last German Pope, he was no better

pleased with it himself. He spoke of his throne as the chair of misery, and

said in his first epitaph, that it was his greatest misfortune to have attained

to power. The epitaph written for his tomb in Santa Maria dell’ Anima by his

faithful servant, the Datary and Cardinal Enckenvoert,

was certainly the best motto for this man and his pontificate

“Pro dolor! quantum refert in quae tempora vel optimi cuiusque virtus incidat”. A Conclave of thirty-three electors

assembled on the 1st of October, 1523. Some sided with the Emperor, some with

the French, but the imperial party was also divided. Pompeo Colonna

made an enemy of the future Pope by opposing his candidature, and Cardinal

Alessandro Farnese in vain offered the ambassadors of both sides 200,000

ducats. Cardinal Wolsey once again made all kinds of offers, but there was now

a feeling against all foreigners. During the night of the 18th-19th of

November Giulio de’ Medici was elected. He was the son of Giuliano,

who fell in the Pazzi conspiracy. A

certain Fioretta, daughter of Antonia, is

mentioned as his mother; little or nothing was known in Florence about her and

her child. Lorenzo took the orphan into his house and had him brought up with

his sons. In 1494 Giulio, then sixteen years of age, followed them into

exile. Living for some time in Lombardy, but mostly with Giovanni, on his

cousin’s rise in power he too was quickly promoted. Leo nominated him

Archbishop of Florence, having specially dispensed him from the canonical

hindrance of his illegitimate birth. At his very first creation of Cardinals on

September 23, 1513, the Pope bestowed on him the title of Cardinal of Santa

Maria in Dominica and made him Legate of Bologna, witnesses having first sworn

to the virtual marriage of his father Giuliano with Fioretta.

During Leo’s reign, as we have already

seen, Cardinal Giulio had almost all the business of government in

his own hands. He secured the election of Adrian, but left Rome and the Pope on

October 13, 1522, in the company of Manuel, the imperial envoy, in order to

retire to Florence. A difference with Francesco Soderini brought

him back in the following April to the Eternal City. He entered it with two

thousand horse, and already greeted as the future Pope kept great state in his

palace. A few days later Francesco Soderini,

accused of high treason, disappeared into the Castle of St Angelo; he was

released during the next Council. With the new reign a return of happier times

was expected “una Corte florida e un buon Pontefice”; the restoration of literature, fled before

the barbarians; “est enim Mediceae familiae decus favereMusis”. And

indeed many things seemed to point to a fortunate pontificate. The new Pope was

respected and rich, and now of a staid and sober life. He had ruled Rome well

in Leo’s day, and as Archbishop of Florence had used his power successfully. He

was cautious, economical, but not avaricious; though not an author himself, an

admirer of art and science; a lover of beautiful buildings, as his

Villa Madama gave proof, and free from his cousin’s unfortunate

liking for the company of worthless buffoons. He did not hunt, but he was fond

of good instrumental music, and liked to amuse himself at table with the

conversation of learned men.

Very soon it became clear that Clement VII

was one of those men, who, though excellent in a subordinate position, prove

unsatisfactory when placed at the head. The characters of both Medici Popes are

wonderfully conceived in Raffaelle’s portraits:

in Leo’s otherwise intellectual face there is a vulgarity that almost

degenerates into coarseness and sensuality, and with Clement the cold soul,

lacking all strong feeling, distrustful, never unfolding itself. “In spite of

all his talents”, said Francesco Vettori, “he

brought the greatest misery on Rome and on himself; he lost courage at once and

let go the rudder”. Guicciardini too complains

of Giulio’s faintheartedness, vacillation and indecision as the chief

source of his misfortune. This indecision kept him wavering between the

counsels of the two men, in whom from the beginning of his reign he placed his

confidence; one belonging to the French faction, the other to that of the

Emperor. One was like himself a bastard, Giammatteo Giberti, rightly valued by all his contemporaries for his

piety, honesty, and insight. He took an active part in the foundation of the

Order of the Theatines (1524) by the pious Gaetano da Thiene, afterwards canonized, in company with Caraffa. He was appointed Datary by Clement, and afterwards

Bishop of Verona. Gasparo Contarini, writing in 1530, says that he was on more

intimate terms with the Pope than were any of his other counsellors, and that

in politics he worked in the French interest. He left the Court in 1527 to

retire to his bishopric, which he made a model of good government. In Verona he

founded a learned society and a Greek printing-press, which published good

editions of the Fathers of the Church. Paul III summoned him to Rome several

times; it was on his way back that he died in 1543.

The Emperor’s interests were represented

by Clement’s other counsellor, Nikolaus von Schomberg, of Meissen, in Saxony. On the occasion of a

journey to Italy in 1497, carried away by the preaching of Savonarola in Pisa,

he had joined the same monastery. Later, scorned by the populace as a Judas, he

had gone over to the party of the Medici, was summoned to Rome as Professor of

Theology by Leo X, created Archbishop of Capua in 1520, and often entrusted

with diplomatic missions, in which capacity Giulio came to know and

value him. Contarini speaks well of him,

but evidently only half trusted him. Schomberg received

the Cardinal’s hat from Paul III in 1534, and died in 1537.

Clement’s accession had at once brought about

a political change in favour of France. The Pope’s policy wavered long between

the King and the Emperor; weak towards both of them, undecided, and on occasion

faithless enough. On January 5,1525, he himself announced to the Emperor the

conclusion of his treaty with Francis I. The Battle of Pavia, the greatest

military event of the sixteenth century (February 24, 1525), made Charles V

master of Italy and Francis I his prisoner. By April 1 Clement had made his

peace with the Emperor, but soon began to intrigue and tried to form a league

against him with Venice, Savoy, Ferrara, Scotland, Hungary, Portugal, and other

States; this was mainly the work of Giberti. At

this time the bold plan of a League of Freedom, which was to claim the

independence of Italy from foreign Powers, was formed by Girolamo Morone; Pescara, the husband of Vittoria Colonna,

the real victor at Pavia, was to stand at its head. The conspiracy in which

Clement on his own confession (see his letter to Charles V of June 23, 1526)

had taken part, was betrayed by Pescara himself; at his instigation Morone named the Pope as the originator of the offers

made to Pescara. The veil of secrecy still covers both Pescara’s

action, Guicciardini characterized it as eterna infamia, and his early death, which occurred on March

30, 1525. The Emperor freely expressed his opinion of the Pope’s faithlessness

(September 17, 1526). On May 22, 1526, Clement concluded the Holy League of

Cognac with Francis, who had returned to France at the beginning of March, his

captivity over. This brought on open war with the Emperor, the attack on Rome

by the Colonna (September 20), the plundering of the Borgo, the march of

the Imperial troops against Rome under the command of Bourbon, the storming of

the part of the city named after Leo in which Bourbon fell (May 6, 1527), the

flight of the Pope to the Castle of St Angelo, and finally the storming of Rome

and the sack which followed it; cruel and revolting to all Christian feeling,

it remains to this day a memory of terror for all Italians. No Guiscard

appeared this time, as in the days of Gregory VII, to save the beleaguered

Pope. On June 5,1527, he was forced to capitulate, yield the fortress and give

himself up to the mercy of the Emperor. When a prisoner and deprived of all his

means, Clement bade Cellini melt down his tiara, a symbol of his own position;

for the whole temporal power of the Papacy lay at the feet of the Emperor, who

could abolish it if he chose. We know that this policy was suggested to him: we

know also that Charles had serious thoughts of utilizing the position of the

Pope for an ecclesiastical reformation, and forcing him to summon the General

Council, which all sides demanded. But France and England declared they would

recognize no Council until the Pope was set free again, and the Spanish clergy

also petitioned for the release of the Head of the Church. Once more the

Imperial troops returned to Rome from their summer quarters, and in September,

1527, the city was once more sacked. Veyre arrived

as the Emperor’s agent to offer Clement freedom on condition of neutrality, a

general peace, and the promotion of reform by means of a Council. The agreement

was signed on November 26; but on December 8 the Pope escaped to Orvieto,

whence on June 1,1528, he removed to Viterbo. The war proved disastrous

for France; Lautrec’s defeats, his death by plague (August 15), the terrible

state of Italy, which was now but one vast battlefield strewn with corpses,

induced Clement at last to side with the Emperor. On October 8, 1528, he

returned horror-stricken to half-burnt, starving Rome. Harried by the plague,

her population diminished by one-half; her importance for the literary and

artistic life of humanity had been for ever marred by the awful events of the

year 1527. Those of her artists and learned men who had not fled were

maltreated and robbed during the Sack: those that were left were beggars and

had to seek their bread elsewhere. Erasmus wrote to Sadoleto (October

1, 1528) that not the city, but the world had perished, and that the present

sufferings of Rome were more cruel than those brought on her by the Goths and

the Gauls. From Carpentras in

1529 Sadoleto wrote a mournful letter

to Colocci, in which he speaks of past glories,

a letter aptly called by Gregorovius the swan’s song,

the farewell to the cheerful world of humanist times.

Clement’s participation in the league against

Charles and the Empire had favoured the spread of the Lutheran Reformation in

Germany. Unwittingly the Pope had become Luther’s best ally at the very moment

when for Catholicism everything depended on strengthening the Emperor’s

opposition to the Reformation, which had the hour in its favour. Even after the

Sack the Pope was not chiefly concerned for the preservation and improvement of

the Church, or for the reparation of the evil done to Rome. What absorbed his

attention were the dynastic interests of his own House, which had once more

been expelled from Florence, and the restoration of the Papal State. The

Emperor could have ended the Temporal Power with a stroke of the pen had he not

feared the immense influence of the clergy and the threatening voice of the

Inquisition, which did not hesitate to cross the threshold even of the most

mighty. Charles needed the Pope, since a lasting enmity with him would have cut

the ground from under his feet both in Spain and Germany. He needed him in

order to keep his hold on Italy, and by his influence to divide the League. And

so the Treaty of Barcelona was brought about (June 29, 1529), whereby the

Emperor acknowledged the power of Sforza in Milan, gave the Papal State back to

the Pope, undertook to restore Florence to the Medici by force of arms, and as

a pledge of friendship to give his illegitimate daughter Margaret to Alessandro

de’ Medici. The Imperial coronation was moreover to take place in Italy. The

“Ladies’ Peace” of Cambray (August 5, 1529) confirmed

Spanish rule in Italy. Clement crowned Charles Emperor on February 24, 1530, in

Bologna, having come thither with sixteen Cardinals. The Emperor left for the

diet at Augsburg on June 15. The Pope returned to Rome on April 9; and on

August 12 Florence fell after a heroic death-struggle, burying the honours of