|

CRISTO RAUL.ORG |

|

THE FRANKSFROM THEIR

FIRST APPEARANCE IN HISTORY TO THE

|

|

THE FRANKS BEFORE CLOVIS

Tacitus, in the de Moribus Germanorum,

tells us that the Germans claimed to be descended from a common ancestor, Mannus, son of the earth-born god Tuisco. Mannus, according to the legend, had three sons, from

whom sprang three groups of tribes: the Istaevones,

who dwelt along the banks of the Rhine; the Ingaevones,

whose seat was on the shores of the two seas, the Oceanus Germanicus (North

Sea) and the Mare Suevicum (the Baltic), and in the Cimbric peninsula between; and, lastly, more to the east

and south, on the banks of the Elbe and the Danube, the Herminones.

After indicating this general division, Tacitus, in the latter part of his

work, enumerates about forty tribes, whose customs presented, no doubt, a

strong general resemblance, but whose institutions and organization showed

differences of a sufficiently marked character.

When we pass from the first century to the fifth, we find that the names of

the Germanic peoples given by Tacitus have completely disappeared. Not only is

there no mention of Istaevones, Ingaevones,

and Herminones, but there is no trace of individual

tribes such as the Chatti, Chauci, and Cherusci; their names are wholly unknown to the writers of

the fourth and fifth centuries. In their place we find these writers using

other designations: they speak of Franks, Saxons, Alemans. The writers of the

Merovingian period not unnaturally supposed that these were the names of new

peoples, who had invaded Germany and made good their footing there in the

interval. This hypothesis found favour especially

with regard to the Franks. As early as Gregory of Tours, we find mention of a

tradition according to which the Franks had come from Pannonia, had first

established themselves on the right bank of the Rhine, and had subsequently

crossed the river. In the chronicler known under the name of Fredegar the Franks are represented as descended from the

Trojans. “Their first king was Priam; afterwards they had a king named Friga; later, they divided into two parts, one of which

migrated into Macedonia and received the name of Macedonians. Those who

remained were driven out of Phrygia and wandered about, with their wives and

children, for many years. They chose for themselves a king named Francion, and from him took the name of Franks. Francion made war upon many peoples, and after devastating

Asia finally passed over into Europe, and established himself between the

Rhine, the Danube and the sea”. The writer of the Liber Historiae combines the statements of Gregory of Tours and of the pseudo-Fredegar, and, with a fine disregard of chronology, relates

that, after the fall of Troy, one part of the Trojan people, under Priam and

Antenor, came by way of the Black Sea to the mouth of the Danube, sailed up the

river to Pannonia, and founded a city called Sicambria. The Trojans, so this

anonymous writer continues, were defeated by the Emperor Valentinian, who laid

them under tribute and named them Franks, that is wild men (feros),

because of their boldness and hardness of heart. After a time the Franks slew

the Roman officials whose duty it was to demand the tribute from them, and, on

the death of Priam, they quitted Sicambria, and came to the neighborhood of the

Rhine. There they chose themselves a king named Pharamond,

son of Marcomir. This naïf legend, half-popular,

half-learned, was accepted as fact throughout the Middle Ages. From it alone

comes the name of Pharamond, which in most histories

heads the list of the kings of France. In reality, there is nothing to prove

that the Franks, any more than the Saxons or the Alemans, were races who came

in from without, driven into Germany by an invasion of their own territory.

Some modern scholars have thought that the origin of the Franks, and of

other races who make their appearance between the third century and the fifth,

might be traced to a curious custom of the Germanic tribes. The nobles, whom

Tacitus calls principes, attached to

themselves a certain number of comrades, comites,

whom they bound to fealty by a solemn oath. At the head of these followers they

made pillaging expeditions, and levied war upon the neighboring peoples,

without however involving the community to which they belonged. The comes was

ready to die for his chief; to desert him would have been an infamy. The chief,

on his part, protected his follower, and gave him a war-horse, spear, etc. as

the reward of his loyalty. Thus there were formed, outside the regular State,

bands of warriors united together by the closest ties. These bands, so it is

said, soon formed, in the interior of Germany, what were virtually new States,

and the former princeps simply took the title of king. Such, according to the

theory, was the origin of the Franks, the Alemans, and the Saxons. But this

theory, however ingenious, cannot be accepted. The bands were formed exclusively

of young men of an age to bear arms; among the Franks we find from the first

old men, women, and children. The bands were organized solely for war; whereas

the most ancient laws of the Franks have much to say about the ownership of

land, and about crimes against property; they represent the Franks as an

organized nation with regular institutions.

The Franks, then, did not come into Germany from without; and it would be

rash to seek their origin in the custom of forming bands. That being so, only

one hypothesis remains open. From the second century to the fourth the Germans

lived in a continual state of unrest. The different communities ceaselessly

made war on one another and destroyed one another. Civil war also devastated

many of them. The ancient communities were thus broken up, and from their

remains were formed new communities which received new names. Thus is to be

explained why it is that the nomenclature of the Germanic peoples in the fifth

century differs so markedly from that which Tacitus has recorded. But neighboring

tribes presented, despite their constant antagonisms, considerable

resemblances. They had a common dialect and similar habits and customs. They

sometimes made temporary alliances, though holding themselves free to quarrel

again before long and make war on one another with the utmost ferocity. In

time, groups of these tribes came to be called by generic names, and this is

doubtless the character of the names Franks, Alemans, and Saxons. These names

were not applied, in the fourth and fifth centuries, to a single tribe, but to

a group of neighboring tribes who presented, along with real differences,

certain common characteristics.

It appears that the peoples who lived along the right bank of the Rhine, to

the north of the Main, received the name of Franks; those who had established

themselves between the Ems and the Elbe, that of Saxons (Ptolemy mentions the Saxones as inhabitants of the Cimbric peninsula, and perhaps the name of this petty tribe had passed to the whole

group); while those whose territory lay to the south of the Main and who at

some time or other had overflowed into the agri decumates (the present Baden) were called

Alemans. It is possible that, after all, we should see in these three peoples,

as Waitz has suggested, the Istaevones, Ingaevones, and Herminones of

Tacitus.

But it must be understood that between the numerous tribes known under each

of the general names of Franks, Saxons, and Alemans there was no common bond.

They did not constitute a single State but groups of States without federal

connection or common organization. Sometimes two, three, even a considerable

number of tribes, might join together to prosecute a war in common, but when

the war was over the link snapped and the tribes fell asunder again.

Franks and Romans. 240-392

Documentary evidence enables us to trace how the generic name Franci came to be given to certain tribes between the Main

and the North Sea, for we find these tribes designated now by the ancient name

which was known to Tacitus and again by the later name. In Peutinger’s chart we find Chamavi qui et Franci and there is no doubt that we should read qui et Franci.

The Chamavi inhabited the country between the Yssel and the Ems; later on, we find them a little further

south, on the banks of the Rhine in Hamaland, and

their laws were collected in the ninth century in the document known as the Lex

Francorum Chamavorum. Along with the Chamavi we may reckon among the Franks the Attuarii or Chattuarii. We read

in Ammianus Marcellinus (xx. 10) Rheno transmisso, regionem pervasit (Julian in AD 360) Francorum quos Atthuarios vocant. Later, the pagus Attuariorum will correspond to the country of Emmerich, of Cleves, and of Xanten. We may

note that in the Middle Ages there was to be found in Burgundy, in the neighborhood

of Dijon, a pagus Attuariorum,

and it is very probable that a portion of this tribe settled at this spot in

the course of the fifth century. The Bructeri, the Ampsivarii, and the Chatti were,

like the Chamavi, reckoned as Franks. They are

mentioned as such in a well-known passage of Sulpicius Alexander which is cited

by Gregory of Tours (Historia Francorum, II. 9). Arbogast, a barbarian general

in the service of Rome, desires to take vengeance on the Franks and their

chiefs—subreguli—Sunno and Marcomir.

It is this Marcomir, chief of the Ampsivarii and Chatti, whom the author of the Liber Historiae makes the father of Pharamond,

though he has nothing whatever to do with the Salian Franks.

Thus it is evident that the name Franks was given to a group of tribes, not

to a single tribe. The earliest historical mention of the name may be that in Peutinger's chart, supposing, at least, that the words et Pranci are not a later interpolation. The earliest mention

in a literary source is in the Vita Aureliani of Vopiscus, cap. 7. In the year 240, Aurelian, who was then

only a military tribune, immediately after defeating the Franks in the neighborhood

of Mainz, was marching against the Persians, and his soldiers as they marched

chanted this refrain:

Mille Sarmatas, mille Francos semel et semel occidimus;

Mille Persas quaerimus.

It would be in any case impossible to follow the history of all these

Frankish tribes for want of evidence, but even if their history was known it

would be of quite secondary interest, for it would have only a remote

connection with the history of France. Offshoots from these various tribes no

doubt established themselves sporadically here and there in ancient Gaul, as in

the case of the Attuarii. It was not however by the

Franks as a whole, but by a single tribe, the Salian Franks, that Gaul was to

be conquered; it was their king who was destined to be the ruler of this noble

territory. It is therefore to the Salian Franks that we must devote our

attention.

The Salian Franks. 358-400

The Salian Franks are mentioned for the first time in AD 358. In that year

Julian, as yet only a Caesar, marched against them. What is the origin of the

name? It was long customary to derive it from the river Yssel (Isala), or from Saalland to the south of the Zuiderzee; but it seems much more probable that the name

comes from sal (the salt sea). The Salian Franks at

first lived by the shores of the North Sea, and were known by this name in

contradistinction to the Ripuarian Franks, who lived on the banks of the Rhine.

All their oldest legends speak of the sea, and the name of one of their

earliest kings, Merovech, signifies sea-born.

From the shores of the North Sea the Salian Franks had advanced little by

little towards the south, and at the period when Ammianus Marcellinus mentions

them they occupied Toxandria, that is to say the

region to the south of the Meuse, between that river and the Scheldt. Julian

completely defeated the Salian Franks, but he left them in possession of their

territory of Toxandria. Only, instead of occupying it

as conquerors, they held it as foederati, agreeing to defend it against all

other invaders. They furnished also to the armies of Rome soldiers whom we hear

of as serving in far distant regions. In the Notitia Dignitatum,

in which we find a sort of Army List of the Empire drawn up about the beginning

of the fifth century, there is mention of Salii senioresand Salii juniores, and we also find Salii figuring in the auxilia palatina.

At the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth century the Salian

Franks established in Toxandria ceased to recognize

the authority of Rome, and began to assert their independence. It was at this

period that the Roman civilization disappeared from these regions. The Latin

language ceased to be spoken and the Germanic tongue was alone employed. Even

at the present day the inhabitants of these districts speak Flemish, a Germanic

dialect. The place-names were altered and took on a Germanic form, with the

terminations hem, ghem, seele, and zele, indicating a dwelling-place, loo

wood, dal valley. The Christian religion retreated along with the Roman

civilization, and those regions reverted to paganism. For a long time, it would

seem, these Salian Franks were held in check by the great Roman road which led,

by way of Arras, Cambrai, and Bavay, to Cologne, and

which was protected by numerous forts.

Clodion, Merovech. 431-451

The Salians were subdivided into a number of tribes each holding a pagus. Each of these divisions had a king who was chosen from

the most noble family, and who was distinguished from his fellow-Franks by his

long hair—criniti reges. The first of

these kings to whom we have a distinct reference bore the name of Clogio or Clojo (Clodion). He had

his seat at Dispargum, the exact position of which

has not been determined—it may have been Diest in

Brabant. Desiring to extend the borders of the Salian Franks he advanced

southwards in the direction of the great Roman road. Before reaching it,

however, he was surprised, near the town of Helena (Hélesmes-Nord),

when engaged in celebrating the betrothal of one of his warriors to a

fair-haired maiden, by Aetius, who exercised in the name of Rome the military

command in Gaul. He sustained a crushing defeat; the victor carried off his

chariots and took prisoner even the trembling bride. This was about the year

431. But Clodion was not long in recovering from this defeat. He sent spies

into the neighborhood of Cambrai, defeated the Romans, and captured the town.

He had thus gained command of the great Roman road. Then, without encountering

opposition, he advanced as far as the Somme, which marked the limit of Frankish

territory. About this period Tournai on the Scheldt seems to have become the

capital of the Salian Franks.

Clodion was succeeded in the kingship of the Franks by Merovech. All our

histories of France assert that he was the son of Clodion; but Gregory of Tours

simply says that he belonged to the family of that king, and he does not give

even this statement as certain; it is maintained, he says, by certain persons.

We should perhaps refer to Merovech certain statements of the Greek historian

Priscus, who lived about the middle of the fifth century. On the death of a

king of the Franks, he says, his two sons disputed the succession. The elder

betook himself to Attila to seek his support; the younger preferred to claim

the protection of the Emperor, and journeyed to Rome. “I saw him there”, he

says; “he was still quite young. His fair hair, thick and very long, fell over

his shoulders”. Aetius, who was at this time in Rome, received him graciously,

loaded him with presents, and sent him back as a friend and ally. Certainly, in

the sequel the Salian Franks responded to the appeal of Aetius and mustered to

oppose the great invasion of Attila, fighting in the ranks of the Roman army at

the battle of the Mauriac Plain (AD 451). The Vita Lupi,

in which some confidence may be placed, names King Merovech among the

combatants.

Various legends have gathered round the figure of Merovech. The pseudo-Fredegar narrates that as the mother of this prince was

sitting by the sea-shore a monster sprang from the waves and overpowered her;

and from this union was born Merovech. Evidently the legend owes its origin to

an attempt to explain the etymology of the name Merovech, son of the sea. In

consequence of this legend some historians have maintained that Merovech was a

wholly mythical personage and they have sought out some remarkable etymologies

to explain the name Merovingian, which is given to the kings of the first

dynasty; but in our opinion the existence of this prince is sufficiently

proved, and we interpret the term Merovingian as meaning descendants of

Merovech.

Childeric. 463

Merovech had a son named Childeric. The relationship is attested in precise

terms by Gregory of Tours who says cujus filius fuit Childericus.

In addition to the legendary narratives about Childeric which Gregory gathered

from oral tradition, we have also some very precise details which the

celebrated historian borrowed from annals now no longer extant. The legendary

tale is as follows. Childeric, who was extremely licentious, dishonored the

daughters of many of the Franks. His subjects therefore rose in their wrath,

drove him from the throne, and even threatened to kill him. He fled to

Thuringia—it is uncertain whether this was Thuringia beyond the Rhine, or

whether there was a Thuringia on the left bank of the river—but he left behind

him a faithful friend whom he charged to win back the allegiance of the Franks.

Childeric and his friend broke a gold coin in two and each took a part.

"When I send you my part", said the friend, "and the pieces fit

together to form one whole you may safely return to your country". The

Franks unanimously chose for their king Aegidius, who had succeeded Aetius in

Gaul as magister militum. At the end of eight

years the faithful friend, having succeeded in gaining over the Franks, sent to

Childeric the token agreed upon, and the prince, on his return, was restored to

the throne. The queen of the Thuringians, Basina by name, left her husband Basinus to follow Childeric. "I know thy worth",

said she, "and thy great courage; therefore I have come to live with thee.

If I had known, even beyond the sea, a man more worthy than thou art, I would

have gone to him". Childeric, well pleased, married her forthwith, and

from their union was born Clovis. This legend, on which it would be rash to

base any historical conclusion, was amplified later, and the further

developments of it have been preserved by the pseudo-Fredegar and the author of the Liber Historiae.

But alongside of this legendary story we have some definite information

regarding Childeric. While the main centre of his

kingdom continued to be in the neighborhood of Tournai, he fought along with the

Roman generals in the valley of the Loire against all the enemies who sought to

wrest Gaul from the Empire. Unlike his predecessor Clodion and his son Clovis,

he faithfully fulfilled his duties as a foederatus. In the year 463 the

Visigoths made an effort to extend their dominions to the banks of the Loire.

Aegidius marched against them, and defeated them at Orleans, Friedrich, brother

of King Theodoric II, being slain in the battle.

Now we know for certain that Childeric was present at this battle. A short

time afterwards the Saxons made a descent, by way of the North Sea, the

Channel, and the Atlantic, under the leadership of a chief named Odovacar,

established themselves in some islands at the mouth of the Loire, and

threatened the town of Angers on the Mayenne. The

situation was the more serious because Aegidius had lately died (October 464),

leaving the command to his son Syagrius. Childeric threw himself into Angers

and held it against the Saxons. He succeeded in beating off the besiegers,

assumed the offensive, and recaptured from the Saxons the islands which they

had seized. The defeated Odovacar placed himself, like Childeric, at the

service of Rome, and the two adversaries, now reconciled, barred the path of a

troop of Alemans who were returning from a pillaging expedition into Italy.

Thus Childeric policed Gaul on behalf of Rome and endeavored to check the

inroads and forays of the other barbarians.

The death of Childeric probably took place in the year 481, and he was

buried at Tournai. His tomb was discovered in the year 1653. In it was a ring

bearing his name, CHILDIRICI REGIS, with the image of the head and shoulders of

a long-haired warrior. Numerous objects of value, arms, jewels, remains of a

purple robe ornamented with golden bees, gold coins bearing the effigies of Leo

I and Zeno, Emperors of Constantinople, were found in the tomb. Such of these

treasures as could be preserved are now in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris. They serve as evidence that

these Merovingian kings were fond of luxury and possessed quantities of

valuable objects. In the ensuing volume it will be seen how Childeric's son

Clovis broke with his father's policy, threw off his allegiance to the Empire,

and conquered Gaul for his own hand. While Childeric was reigning at Tournai,

another Salian chief, Ragnachar, reigned at Cambrai,

the town which Clodion had taken; the residence of a third, named Chararic, is unknown to us.

The Ripuarian Franks. 360-481

The Salian Franks, as we have said above, were so called in

contradistinction to the Ripuarians. The latter doubtless included a certain

number of tribes, such as the Ampsivarii and the Bructeri. Julian, in the year 360, checked the advance of

these barbarians and forced them to retire across the Rhine. In 389 Arbogast

similarly checked their inroads and conquered all their territory in 392, as we

have already said. But in the beginning of the fifth century, when Stilicho had

withdrawn the Roman garrisons from the banks of the Rhine, they were able to

advance without hindrance and establish themselves on the left bank of the

river. Their progress however was far from rapid. They only gained possession

of Cologne at a time when Salvian, born about 400,

was a man in middle life; and even then the town was retaken. It did not

finally pass into their hands until the year 463. The town of Treves was taken

and burned by the Franks four times before they made themselves masters of it.

Towards 470 the Ripuarians had founded a fairly compact kingdom, of which the

principal cities were Aix-la-Chapelle, Bonn, Juliers,

and Zülpich. They had advanced southwards as far as Divodurum (Metz), the fortifications of which seem to have

defied all their efforts. The Roman civilization, the Latin language, and even

the Christian religion seem to have disappeared from the regions occupied by

the compact masses of these invaders. The present frontier of the French and

German languages, or a frontier drawn a little further to the south—for it

appears that in course of time French has gained ground a little—indicates the

limit of their dominions. In the course of their advance southwards, the

Ripuarians came into collision with the Alemans, who had already made

themselves masters of Alsace and were endeavoring to enlarge their borders in

all directions. There were many battles between the Ripuarians and Alemans, of

one of which, fought at Zülpich (Tolbiacum),

a record has been preserved. Sigebert, king of the Ripuarians, was there

wounded in the knee and walked lame for the rest of his life; whence he was

known as Sigebertus Claudus.

It appears that at this time the Alemans had penetrated far north into the

kingdom of the Ripuarians. This kingdom was destined to have but a transient

existence; we shall see in the following volume how it was destroyed by Clovis,

and how all the Frankish tribes on the left bank of the Rhine were brought

under his authority.

While the Salian and Ripuarian Franks were spreading along the left bank of

the Rhine, and founding flourishing kingdoms there, other Frankish tribes

remained on the right bank. They were firmly established, especially to the

north of the Main, and among them the ancient tribe of the Chatti,

from whom the Hessians are derived, took a leading place. Later this territory

formed one of the duchies into which Germany was divided, and took from its

Frankish inhabitants the name of Franconia.

The Salic Law. 507-511

If we desire to make ourselves acquainted with the manners and customs of

the Franks, we must have recourse to the most ancient document which has come

down from them—the Salic Law. The oldest redaction of this Law, as will be

shown in the next volume, probably dates only from the last years of Clovis

(507-511), but in it are codified much more ancient usages. On the basis of

this code we can conjecture the condition of the Franks in the time of Clodion,

of Merovech, and of Childeric. The family is still a very closely united whole;

there is solidarity among relatives even to a remote degree. If a murderer

could not pay the fine to which he had been sentenced, he must bring before the mâl (court) twelve comprobators who made affirmation that he could not pay it. That done, he returned to his dwelling,

took up some earth from each of the four corners of his room, and cast it with

the left hand over his shoulder towards his nearest relative; then, barefoot

and clad only in his shirt, but bearing a spear in his hand, he leaped over the

hedge which surrounded his dwelling. Once this ceremony had been performed, it

devolved upon his relative, to whom he had thereby ceded his house, to pay the

fine in his place. He might appeal in this way to a series of relatives one

after another; and if, ultimately, none of them was able to pay, he was brought

before four successive mâls, and if no one took pity

on him and paid his debt, he was put to death. But if the family was thus a

unit for the payment of fines, it had the compensating advantage of sharing the

fine paid for the murder of one of its members. Since the solidarity of the

family sometimes entailed dangerous consequences, it was permissible for an

individual to break these family ties. The man who wished to do so presented

himself at the mâl before the centenarius and broke into four pieces, above his

head, three wands of alder. He then threw the pieces into the four corners,

declaring that he separated himself from his relatives and renounced all rights

of succession. The family included the slaves and liti or freedmen. Slaves were the chattels of their master; if they were wounded,

maimed, or killed, the master received the compensation; on the other hand, if

the slave had committed any crime the master was obliged to pay, unless he

preferred to give him up to bear the punishment. The Franks recognized private

property, and severe penalties were denounced against those who invaded the

rights of ownership; there are penalties for stealing from another's garden,

meadow, corn-field, or flax-field, and for ploughing another's land. At a man's

death all his property was divided among his sons; a daughter had no claim to

any share of it. Later, she is simply excluded from Salic ground, that is from

her father's house and the land that surrounds it.

We find also in the Salic Law some information about the organization of

the State. The royal power appears strong. Any man who refuses to appear before

the royal tribunal is outlawed. All his goods are confiscated and anyone who

chooses may slay him with impunity; no one, not even his wife, may give him

food, under penalty of a very heavy fine. All those who are employed about the

king's person are protected by a special sanction. Their wergeld is three times as high as that of other Franks of the same social status. Over

each of the territorial divisions called pagi the king placed a representative of his authority known as the grafio, or, to give him his later title, the comes.

The grafio maintained order within his

jurisdiction, levied such fines as were due to the king, executed the sentences

of the courts, and seized the property of condemned persons who refused to pay

their fines. The pagus was in turn subdivided

into "hundreds" (centenae). Each

"hundred" had its court of judgment known as the mâl;

the place where it met was known as the mâlberg.

This tribunal was presided over by the centenarius or thunginus—these terms appear to us to be

synonymous. Historians have devoted much discussion to the question whether

this official was appointed by the king or elected by the freemen of the

"hundred". At the court of the "hundred" all the freemen

had a right to be present, but only a few of them took part in the

proceedings—some of them would be nominated for this duty on one occasion, some

on another. In their capacity as assistants to the centenarius at the mâl the freemen were designated rachineburgi. In order to make a sentence valid it

was required that seven rachineburgi should

pronounce judgment. A plaintiff had the right to summon seven of them to give

judgment upon his suit. If they refused, they had to pay a fine of three sols.

If they persisted in their refusal, and did not undertake to pay the three sols

before sunset, they incurred a fine of fifteen sols.

Crimes and Offences

Every man’s life was rated at a certain value; this was his price, the wergeld. The wergeld of a Salian

Frank was 200 sols; that of a Roman 100 sols. If a Salian Frank had killed

another Salian, or a Roman, without aggravating circumstances, the Court

sentenced him to pay the price of the victim, the 200 or 100 sols. The compositio in this case is exactly equivalent to the wergeld; if, however, he had only wounded his victim

he paid, according to the severity of the injury, a lower sum proportionate to

the wergeld. If, however, the murder has taken

place in particularly atrocious circumstances, if the murderer has endeavored

to conceal the corpse, if he has been accompanied by an armed band, or if the

assassination has been unprovoked, the compositio may be three times, six times, nine times, the wergeld.

Of this compositio, two thirds were paid to

the relatives of the victim; this was the faida and

bought off the right of private vengeance; the other third was paid to the

State or to the king: it was called fretus or fredum from the German word Friede peace, and was a compensation for the breach of the public peace of which the

king is the guardian. Thus a very lofty principle was embodied in this penalty.

The Salic Law is mainly a tariff of the fines which must be paid for various

crimes and offences. The State thus endeavored to substitute the judicial

sentences of the courts for private vengeance, part of the compensation being

paid to the victim or his family to induce them to renounce this right. But we

may safely conjecture that the triumph of law over inveterate custom was not

immediate. It was long before families were willing to leave to the judgment of

the courts serious crimes which had been committed against them, such as

homicides and adulteries; they flew to arms and made war upon the guilty person

and his family. The forming in this way of armed bands was very detrimental to

public order.

The crimes mentioned most frequently in the Salic Law give us some grounds

on which to form an idea of the manners and characteristics of the Franks.

These Franks would seem to have been much given to bad language, for the Law

mentions a great variety of terms of abuse. It is forbidden to call one’s

adversary a fox or a hare, or to reproach him with having flung away his

shield; it is forbidden to call a woman meretrix, or to say that she had joined

the witches at their revels. Warriors who are so easily enraged readily pass to

violence and murder. Every form of homicide is mentioned in the Salic Law. The

roads are not safe, and are often infested by armed bands. In addition to

murder, theft is very often mentioned by the code — theft of fruits, of hay, of

cattle-bells, of horse-clogs, of animals, of river-boats, of slaves, and even

of freemen. All these thefts are punished with severity and are held by all to

be base and shameful crimes. But there is a punishment of special severity for

robbing a corpse which has been buried. The guilty person is outlawed, and is

to be treated like a wild beast.

The civilization of these Franks is primitive; they are, above all else,

warriors. As to their appearance, they brought their fair hair forward from the

top of the head, leaving the back of the neck bare. On their faces they

generally wore no hair but the moustache. They wore close-fitting garments,

fastened with brooches, and bound in at the waist by a leather belt which was

covered with bands of enameled iron and clasped by an ornamental buckle. From

this belt hung the long sword, the hanger or scramasax, and various articles of

the toilet, such as scissors and combs made of bone. From it too was hung the

single-bladed axe, the favorite weapon of the Franks, known as the francisca, which they used both at close quarters

and by hurling it at their enemies from a distance. They were also armed with a

long lance or spear formed of an iron blade at the end of a long wooden shaft.

For defense they carried a large shield, made of wood or wattles covered with

skins, the centre of which was formed by a convex

plate of metal, the boss, fastened by iron rods to the body of the shield. They

were fond of jewellery, wearing gold finger-rings and

armlets, and collars formed of beads of amber or glass or paste inlaid with color.

They were buried with their arms and ornaments, and many Frankish cemeteries have

been explored in which the dead were found fully armed, as if prepared for a

great military review. The Franks were universally distinguished for courage.

As Sidonius Apollinaris wrote of them: "from their youth up war is their

passion. If they are crushed by weight of numbers, or through being taken at a

disadvantage, death may overwhelm them, but not fear."

I.

FROM THE FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE FRANKS TO THE DEATH

OF CLOVIS

(AD. 240-511)

It is well known that the name of “Frank” is not to be found in the long

list of German tribes preserved to us in the “Germania” of Tacitus. Little or

nothing is heard of them before the reign of Gordian III. In AD 240 Aurelian,

then a tribune of the sixth legion stationed on the Rhine, encountered a body

of marauding Franks near Mayence, and drove them

back into their marshes. The word “Francia” is also found at a still earlier

date, in the old Roman chart called the Charta Peutingeria,

and occupies on the map the right bank of the Rhine from opposite Coblentz to

the sea. The origin of the Franks has been the subject of frequent debate, to

which French patriotism has occasionally lent some asperity. At the time when

they first appear in history, the Romans had neither the taste nor the means

for historical research, and we are therefore obliged to depend in a great

measure upon conjecture and combination. It has been disputed whether the word

“Frank” was the original designation of a tribe, which by a change of

habitation emerged at the period above mentioned into the light of history, or

that of a new league, formed for some common object of aggression or defence, by nations hitherto familiar to us under other

names.

We can in this place do little more than refer to a controversy, the value

and interest of which has been rendered obsolete by the progress of historical

investigation. The darkness and void of history have as usual been filled with

spectral theories, which vanish at the challenge of criticism and before the

gradually increasing light of knowledge.

We need hardly say that the origin of the Franks has been traced to

fugitive colonists from Troy; for what nation under Heaven has not sought to

connect itself, in some way or other, with the glorified heroes of the immortal

song? Nor is it surprising that French writers, desirous of transferring from

the Germans to themselves the honors of the Frankish name, should have made of

them a tribe of Gauls, whom some unknown cause had induced to settle in

Germany, and who afterwards sought to recover their ancient country from the

Roman conquerors. At the present day, however, historians of every nation,

including the French, are unanimous in considering the Franks as a powerful

confederacy of German tribes, who in the time of Tacitus inhabited the

north-western parts of Germany bordering on the Rhine. And this theory is so

well supported by many scattered notices, slight in themselves, but powerful

when combined, that we can only wonder that it should ever have been called in

question. Nor was this aggregation of tribes under the new name of Franks a

singular instance; the same took place in the case of the Alemanni and Saxons.

The actuating causes of these new unions are unknown. They may be sought

for either in external circumstances, such as the pressure of powerful enemies

from without, or in an extension of their own desires and plans, requiring the

command of greater means, and inducing a wider co-operation of those, whose

similarity of language and character rendered it most easy for them to unite.

But perhaps we need look no farther for an efficient cause than the spirit of

amalgamation which naturally arises among tribes of kindred race and language,

when their growing numbers, and an increased facility of moving from place to

place, bring them into more frequent contact. The same phenomenon may be

observed at certain periods in the history of almost every nation, and the

spirit which gives rise to it has generally been found strong enough to

overcome the force of particular interests and petty nationalities.

SICAMBRI AND SALIAN FRANKS.

The etymology of the name adopted by the new confederacy is also uncertain.

The conjecture which has most probability in its favor is that adopted long ago

by Gibbon, and confirmed in recent times by the authority of Grimm, which

connects it with the German word Frank (free). The derivation preferred

by Adelung from frak,

with the inserted nasal, differ of Grimm only in appearance. No small

countenance is given to this derivation by the constant recurrence in after

times of the epithet “truces”, “feroces”, which the

Franks were so fond of applying to themselves, and which they certainly did

everything to deserve. Tacitus speaks of nearly all the tribes, whose various

appellations were afterwards merged in that of Frank, as living in the

neighborhood of the Rhine. Of these the principal were the Sicambri (the chief

people of the old Iscaevonian tribe), who,

as there is reason to believe, were identical with the Salian Franks. The

confederation further comprised the Bructeri,

the Ghamavi, Ansibarii, Tubantes, Marsi, and Chasuarii, of

whom the five last had formerly belonged to the celebrated Cheruscan league, which, under the hero Arminius,

destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburgian Forest.

The strongest evidence of the identity of these tribes with the Franks, is the

fact that, long after their settlement in Gaul, the distinctive names of the

original people were still occasionally used as synonymous with that of the

confederation. The Sicambri are well known in the Roman history for their

active and enterprising spirit, and the determined opposition which they

offered to the greatest generals of Rome. It was on their account that Caesar

bridged the Rhine in the neighborhood of Bonn, and spent eighteen days, as he

informs us with significant minuteness, on the German side of that river.

Drusus made a similar attempt against them with little better success. Tiberius

was the first who obtained any decided advantage over them; and even he, by his

own confession, was obliged to have recourse to treachery. An immense number of

them were then transported by the command of Augustus to the left bank of the

Rhine, “that”, as the Panegyrist expresses it, “they might be compelled to lay

aside not only their arms but their ferocity”. That they were not, however,

even then, so utterly destroyed or expatriated as the flatterers of the Emperor

would have us believe, is evident from the fact that they appear again under the

same name, in less than three centuries afterwards, as the most powerful tribe

in the Frankish confederacy.

The league thus formed was subject to two strong motives, either of which

might alone have been sufficient to impel a brave and active people into a

career of migration and conquest. The first of these was necessity, the actual

want of the necessaries of life for their increasing population, and the second

desire, excited to the utmost by the spectacle of the wealth and civilization

of the Gallic provinces.

As long as the Romans held firm possession of Gaul, the Germans could do

little to gratify their longings; they could only obtain a settlement in that

country by the consent of the Emperor and on certain conditions. Examples of

such merely tolerated colonization were the Tribocci, the Vangiones, and the Ubii at

Cologne. But when the Roman Empire began to feel the numbness of approaching

dissolution, and, as is usually the case, first in its extremities, the Franks

were amongst the most active and successful assailants of their enfeebled foe:

and if they were attracted towards the West by the abundance they beheld of all

that could relieve their necessities and gratify their lust of spoil, they were

also impelled in the same direction by the Saxons, the rival league, a people

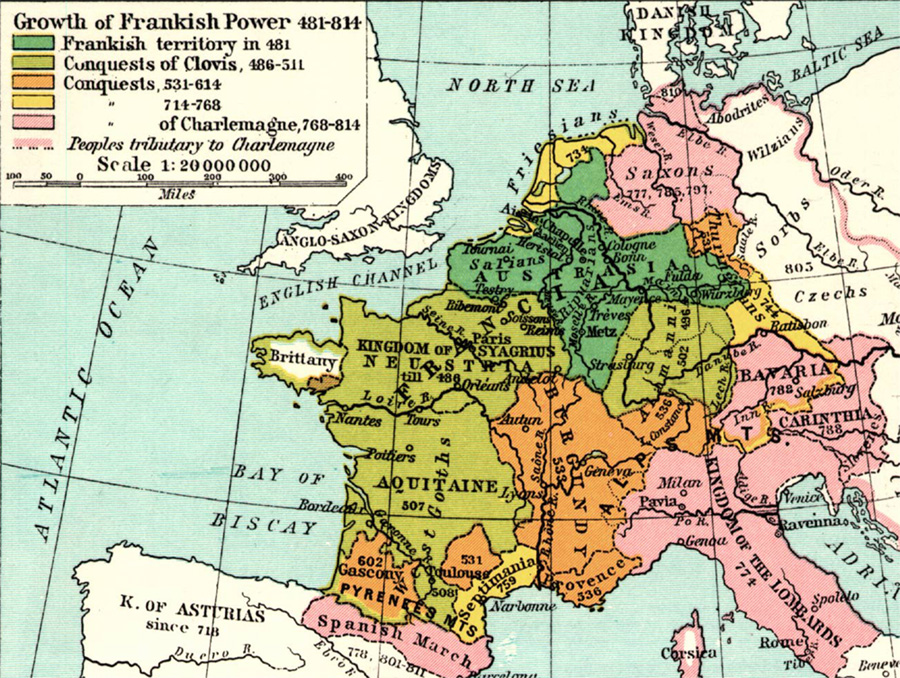

as brave and perhaps more barbarous than themselves. A glance at the map of

Germany of that period will do much to explain to us the migration of the

Franks, and that long and bloody feud between them and the Saxons, which began

with the Gatti and Cherusci and

needed all the power and energy of a Charlemagne to bring to a successful

close. The Saxons formed behind the Franks, and could only reach the provinces

of Gaul by sea. It was natural therefore that they should look with the intensest hatred upon a people who barred their

progress to a more genial climate and excluded them from their share in the

spoils of the Roman world.

The Franks advanced upon Gaul from two different directions, and under the

different names of Salians, and Ripuarians, the former of whom we have reason

to connect more particularly with the Sicambrian tribe.

The origin of the words Salian and Ripuarian, which are first used respectively

by Ammianus Marcellinus and Jordanes, is very obscure, and has served to

exercise the ingenuity of ethnographers. There are, however, no sufficient

grounds for a decided opinion. At the same time it is by no means improbable

that the river Yssel, Isala or

Sal (for it has borne all these appellations), may have given its name to that

portion of the Franks who lived along its course. With still greater

probability may the name Ripuarii or Riparii, be derived from Ripa,

a term used by the Romans to signify the Rhine. These dwellers on the Bank were

those that remained in their ancient settlements while their Salian kinsmen

were advancing into the heart of Gaul.

It would extend the introductory portion of this work beyond its proper

limits to refer, however briefly, to all the successive efforts of the Franks

to gain a permanent footing upon Roman ground. Though often defeated, they

perpetually renewed the contest; and when Roman historians and panegyrists

inform us that the whole nation was several times “utterly destroyed” the

numbers and geographical position in which we find them a short time after

every such annihilation, prove to us the vanity of such accounts. Aurelian, as

we have seen, defeated them at Mayence, in AD 242,

and drove them into the swamps of Holland. They were routed again about twelve

years afterwards by Gallienus; but they quickly recovered from this blow, for

in AD 276 we find them in possession of sixty Gallic cities,

of which Probus is said to have deprived them, and to have destroyed

400,000 of them and their allies on Roman ground. In AD 280,

they gave their aid to the usurper Proculus, who

claimed to be of Frankish blood, but was nevertheless betrayed by them; and

in AD 288, Carausius the Menapian was

sent to clear the seas of their roving barks. But the latter found it more

agreeable to shut his eyes to their piracies, in return for a share of the

booty, and they afterwards aided in protecting him from the chastisement due to

his treachery, and in investing him with the imperial purple in Britain.

In the reign of Maximian, we find a Frankish army, probably of Ripuarians,

at Treves, where they were defeated by that emperor; and both he and Diocletian

adopted the title of “Francicus”, which many

succeeding emperors were proud to bear. The first appearance of the Salian

Franks, with whom this history is chiefly concerned, is in the occupation of

the Batavian Islands, in the Lower Rhine. They were attacked in that territory

in ad 292, by Constantius Chlorus, who, as is

said, not only drove them out of Batavia, but marched, triumphant and

unopposed, through their own country as far as the Danube. The latter part of

this story has little foundation either in history or probability.

The more determined and successful resistance to their progress was made by

Constantine the Great, in the first part of the fourth century. We must,

however, receive the extravagant accounts of the imperial annalists with

considerable caution. It is evident, even from their own language, that the

great emperor effected more by stratagem than by force. He found the Salians

once more in Batavia, and, after defeating them in a great battle, carried off

a large number of captives to Treves, the chief residence of the emperor, and a

rival of Rome itself in the splendor of its public buildings.

It was in the circus of this city, and in the presence of Constantine, that

the notorious “Ludi Francici”

were celebrated; at which several thousand Franks, including their kings Regaisus and Ascaricus,

were compelled to fight with wild beasts, to the inexpressible delight of the

Christian spectators. “Those of the Frankish prisoners”, says Eumenius, “whose perfidy unfitted them for military

service, and their ferocity for servitude, were given to the wild beasts as a

show, and wearied the raging monsters by their multitude”. “This magnificent

spectacle” Nazarius praises, some twenty

years after it had taken place, in the most enthusiastic terms, comparing

Constantine to a youthful Hercules who had strangled two serpents in the cradle

of his empire. Eumenius calls it a “daily

and eternal victory”, and says that Constantine had erected terror as a bulwark

against his barbarian enemies. This terror did not, however, prevent the Franks

from taking up arms to revenge their butchered countrymen, nor the Alemanni

from joining in the insurrection. The skill and fortune of Constantine

generally prevailed; he destroyed great numbers of the Franks and the “innumeroe gentes”

who fought on their side, and really appears for a time to have checked their

progress.

It is impossible to read the brief yet confused account of these incessant

encounters between the Romans and Barbarians, without coming to the conclusion

that only half the truth is told; that while every advantage gained by the

former is greatly exaggerated, the successes of the latter are passed over in

silence. The most glorious victory of a Roman general procures him only a few

months repose, and the destruction of “hundreds of thousands” of Franks and Alemanni

seems but to increase their numbers. We may fairly say of the Franks, what

Julian and Eutropius have said respecting the Goths, that they were not so

utterly annihilated as the panegyrists pretend, and that many of the victories

gained over them cost “more money than blood”.

The death of Constantine was the signal for a fresh advance on the part of

the Franks. Libanius, the Greek rhetorician, when extolling the deeds of

Constans, the youngest son of Constantine the Great, says that the emperor

stemmed the impetuous torrent of barbarians “by a love of war even greater than

their own”. He also says that they received overseers; but this was no doubt on

Roman ground, which would account for their submission, as we know that the

Franks were more solicitous about real than nominal possession. During the

frequent struggles for the Purple which took place at this period, the aid of

the Franks was sought for by the different pretenders, and rewarded, in case of

success, by large grants of land within the limits of the empire. The barbarians

consented, in fact, to receive as a gift what had really been won by their own

valor, and could not have been withheld. Even previous to the reign of

Constantine, some Frankish generals had risen to high posts in the service of

Roman emperors. Magnentius, himself a German, endeavored to support his

usurpation by Frankish and Saxon mercenaries; and Silvanus, who was driven into

rebellion by the ingratitude of Constantius, whom he had faithfully served, was

a Frank.

The state of confusion into which the empire was thrown by the turbulence

and insolence of the Roman armies, and the selfish ambition of their leaders,

was highly favorable to the progress of the Franks in Gaul. Their next great

and general movement took place in ad 355, when, along the whole Roman frontier

from Strasburg to the sea, they began to cross the Rhine, and to throw

themselves in vast numbers upon the Gallic provinces, with the full

determination of forming permanent settlements. But again the relenting fates

of Rome raised up a hero in the person of the Emperor Julian, worthy to have

lived in the most glorious period of her history. After one or two unsuccessful

efforts, Julian succeeded in retaking Cologne and other places, which the

Germans, true to their traditionary hatred of walled towns, had laid bare of

all defenses.

THE SALIANS AT

TOXANDRIA.

In the last general advance of the Franks in ad 355, the Salians had not

only once more recovered Batavia, but had spread into Toxandria,

in which they firmly fixed themselves. It is important to mark the date of this

event, because it was at this time that the Salians made their first permanent

settlement on the left bank of the Rhine, and by the acquisition of Toxandria laid the foundation of the kingdom of

Clovis. Julian indeed attacked them there in ad 358, but he had probably good

reasons for not reducing them to despair, as we find that they were permitted

to retain their newly acquired lands, on condition of acknowledging themselves

subjects of the empire.

He was better pleased to have them as soldiers than as enemies, and they,

having felt the weight of his arm, were by no means averse to serve in his

ranks, and to enrich themselves by the plunder of the East. Once in undisputed

possession of Toxandria, they gradually spread

themselves further and further, until, at the beginning of the fifth century,

we find them occupying the left bank of the Rhine; as may safely be inferred

from the fact that Tongres, Arras, and Amiens

are mentioned as the most northern of the Roman stations. At this time they

reached Tournai, which became henceforth the chief town of the Salian

Franks. The Ripuarians, meanwhile, were extending themselves from Andernach downwards along the middle Rhine, and gained

possession of Cologne about the time of the conquest of Tournai by

their Salian brethren. On the left of the river they held all that part of

Germania Secunda which was not occupied by

the Salians. In Belgica Secunda,

they spread themselves as far as the Moselle, but were not yet in

possession of Treves, as we gather from the frequent assaults made by them upon

that city. The part of Gaul therefore now subject to the Ripuarians was bounded

on the north-west by the Silva Carbonaria,

or Kolhenwald; on the south-west by the Meuse

and the forest of Ardennes; and on the south by the Moselle.

We shall be the less surprised that some of the fairest portions of the

Roman Empire should thus fall an almost unresisting prey to barbarian invaders,

when we remember that the defence of the

empire itself was sometimes committed to the hands of Frankish soldiers. Those

of the Franks who were already settled in Gaul, were often engaged in endeavoring

to drive back the ever-increasing multitude of fresh barbarians, who hurried

across the Rhine to share in the bettered fortunes of their kinsmen, or even to

plunder them of their newly-acquired riches. Thus Mallobaudes,

who is called king of the Franks, and held the office of Domesticorum Comes under Gratian,

commanded in the Imperial army which defeated the Alemanni at Argentaria.

And, again, in the short reign of Maximus, who assumed the purple in Gaul,

Spain, and Britain, near the end of the fourth century, we are told that three

Frankish kings, Genobaudes, Marcomeres, and Sunno, crossed

the Lower Rhine, and plundered the country along the river as far as Cologne;

although the whole of Northern Gaul was already in possession of their

countrymen. The generals Nonnius and Quintinus, whom Maximus had left behind him at Treves, the

seat of the Imperial government in Gaul, hastened to Cologne, from which the

marauding Franks had already retired with their booty. Quintinus crossed

the Rhine, in pursuit, at Neus, and, unmindful

of the fate of Varus in the Teutoburgian wood,

followed the retreating enemy into the morasses. The Franks, once more upon

friendly and familiar ground, turned upon their pursuers, and are said to have

destroyed nearly the whole Roman army with poisoned arrows.

The war continued, and was only brought to a successful conclusion for the

Romans by the courage and conduct of Arbogastes,

a Frank in the service of Theodosius. Unable to make peace with his barbarous

countrymen, and sometimes defeated by them, this general crossed the Rhine when

the woods were leafless, ravaged the country of the Chamavi, Bructeri, and Catti, and having slain two of their

chiefs named Priam and Genobaudes,

compelled Marcomeres and Sunno to give hostages. The submission of the Franks

must have been of short continuance, for we read that in ad 398 these same

kings, Marcomeres and Sunno, were again found ravaging the left bank of the Rhine

by Stilicho. This famous warrior defeated them in a great battle, and sent

the former, or perhaps both of them, in chains to Italy, where Marcomeres died in prison.

The first few years of the fifth century are occupied in the struggle

between Alaric the Goth and Stilicho, which ended in the sacking of Rome by the

former in the year 410 ad, the same in which he died.

While the Goths were inflicting deadly wounds on the very heart of the

empire, the distant provinces of Germany and Gaul presented a scene of

indescribable confusion. Innumerable hosts of Astingians,

Vandals, Alani, Suevi, and Burgundians, threw themselves like robbers upon

the prostrate body of Imperial Rome, and scrambled for the gems which fell from

her costly diadem. In such a storm the Franks could no longer sustain the part

of champions of the empire, but doubtless had enough to do to defend themselves

and hold their own. We can only guess at the fortune which befell the nations

in that dark period, from the state in which we find them when the glimmering

light of history once more dawns upon the chaos.

PHARAMOND A MYTHICAL PERSONAGE

Of the internal state of the Frankish league in these times, we learn from

ancient authorities absolutely nothing on which we can safely depend. The blank

is filled up by popular fable. It is in this period, about 417 ad, that the

reign of Pharamond is placed, of whom we

may more than doubt whether he ever existed at all. To this hero was

afterwards ascribed, not only the permanent conquests made at this juncture by

the various tribes of Franks, but the establishment of the monarchy, and the

collection and publication of the well-known Salic laws. The sole

foundation for this complete and harmonious fabric is a passage interpolated

into an ancient chronicle of the fifth century; and, with this single

exception, Pharamond’s name is never

mentioned before the seventh century. The whole story is perfected and rounded

off by the author of the “Gesta Francorum”, according

to whom, Pharamond was the son of Marcomeres, the prince who ended his days in the

Italian prison. The fact that nothing is known of him by Gregory of Tours

or Fredegarius is sufficient to prevent our regarding him as an

historical personage. To this may be added that he is not mentioned in the

prologue of the Salic law, with which his name has been so intimately

associated by later writers.

Though well authenticated names of persons and places fail us at this time,

it is not difficult to conjecture what must have been the main facts of the

case. Great changes took place among the Franks, in the first half of the fifth

century, which did much to prepare them for their subsequent career. The

greater portion of them had been mere marauders, like their German brethren of

other nations: they now began to assume the character of settlers; and as the

idea of founding an extensive empire was still far from their thoughts, they

occupied in preference the lands which lay nearest to their ancient homes.

There are many incidental reasons which make this change in their mode of life

a natural and inevitable one. The country whose surface had once afforded a

rich and easily collected booty, and well repaid the hasty foray of weeks, and

even days, had been stripped of its movable wealth by repeated incursions of

barbarians still fiercer than themselves. All that was above the surface the

Alan and the Vandal had swept away, the treasures which remained had to be

sought for with the plough. The Franks were compelled to turn their attention

to that agriculture which their indolent and warlike fathers had hated; which

required fixed settlements, and all the laws of property and person

indissolubly connected therewith. Again, though there is no sufficient reason

to connect the Salic laws with the mythical name of Pharamond, or to suppose that they were altogether the work

of this age (since we know from Tacitus that the Germans had similar laws in

their ancient forests), yet it is very probable was insufficiently defended, he

advanced upon that city, and succeeded in taking it. After spending a few days

within the walls of his new acquisition, he marched as far as the river Somme.

His progress was checked by Aetius and Majorian, who surprised him in the

neighborhood of Arras, at a place called Helena (Lens), while celebrating a

marriage, and forced him to retire. Yet at the end of the war, the Franks

remained in full possession of the country which Clodion had overrun; and the

Somme became the boundary of the Salian land upon the south-west, as it

continued to be until the time of Clovis.

Clodion died in AD 448, and was thus saved from the

equally pernicious alliance or enmity of the ruthless conqueror Attila. This

“Scourge of God”, as he delighted to be called, appeared in Gaul about the year

450 AD, at the head of an innumerable host of mounted Huns; a race

so singular in their aspect and habits as to seem scarcely human, and compared

with whom, the wildest Franks and Goths must have appeared rational and

civilized beings.

FRANKS AT CHÂLONS.

The time of Attila’s descent upon the Rhine was well chosen for the

prosecution of his scheme of universal dominion. Between the fragment of the

Roman Empire, governed by Aetius, and the Franks under the successors of

Clodion, there was either open war or a hollow truce. The succession to the

chief power in the Salian tribe was the subject of a violent dispute between

two Frankish princes, the elder of whom is supposed by some to have been

called Merovaeus. We have seen reason to doubt

the existence of a prince of this name; and there is no evidence that either of

the rival candidates was a son of Clodion. Whatever their parentage or name may

have been, the one took part with Attila, and the other with the Roman Aetius,

on condition, no doubt, of having their respective claims allowed and supported

by their allies. In the bloody and decisive battle of the Catalaunian Fields round Châlons, Franks, under the

name of Leti and Ripuarii,

served under the so-called Merovaeus in the

army of Aetius, together with Theoderic and

his Visigoths. Among the forces of Attila another body of Franks was arrayed,

either by compulsion, or instigated to this unnatural course by the fierce

hatred of party spirit. From the result of the battle of Châlons, we must

suppose that the ally of Aetius succeeded to the throne of Clodion.

The effects of the invasion of Gaul by Attila were neither great nor

lasting, and his retreat left the German and Roman parties in much the same

condition as he found them. The Roman Empire indeed was at an end in that

province, yet the valor and wisdom of Egidius enabled

him to maintain, as an independent chief, the authority which he had faithfully

exercised, as Master-General of Gaul, under the noble and virtuous Magorian. The extent of his territory is not clearly

defined, but it must have been, in part at least, identical with that of which

his son and successor, Syagrius, was deprived by Clovis. Common opinion limits

this to the country between the Oise, the Marne, and the Seine, to which some

writers have added Auxerre and Troyes. The respect in which Egidius was held by the Franks, as well as his own

countrymen, enabled him to set at defiance the threats and machinations of the

barbarian Ricimer, who virtually ruled at Rome, though in another's name. The

strongest proof of the high opinion they entertained of the merits of Egidius, is said to have been given by the Salians in the

reign of their next king. The prince, to whom the name Merovaeus has

been arbitrarily assigned, was succeeded by his son Childeric, in ad 456. The

conduct of this licentious youth was such as to disgust and alienate his

subjects, who had not yet ceased to value female honor, nor adopted the loose

manners of the Romans and their Gallic imitators. The authority of the Salian

kings over the fierce warriors of their tribe was held by a precarious tenure.

The loyalty which distinguished the Franks in later times had not yet arisen in

their minds, and they did not scruple to send the corrupter of their wives and

daughters into ignominious exile. Childeric took refuge with Bissinus(or Bassinus), king

of the Thuringians, a people dwelling on the river Unstrut.

It was then that the Franks, according to the somewhat improbable account of

Gregory, unanimously chose Egidius for

their king, and actually submitted to his rule for the space of eight years. At

the end of that period, returning affection for their native prince, the mere

love of change, or the machinations of a party, induced the Franks to recall

Childeric from exile, or, at all events, to allow him to return. Whatever may

have been the cause of his restoration, it does not appear to have been the

consequence of an improvement in his morals. The period of his exile had been

characteristically employed in the seduction of Basina, the wife of his

hospitable protector at the Thuringian Court. This royal lady, whose character

may perhaps do something to diminish the guilt of Childeric in our eyes, was

unwilling to be left behind on the restoration of her lover to his native

country. Scarcely had he re-established his authority when he was unexpectedly

followed by Basina, whom he immediately married. The offspring of this

questionable alliance was Clovis, who was born in the year 466. The remainder

of Childeric’s reign was chiefly spent in a struggle with the Visigoths, in

which Franks and Romans, under their respective leaders, Childeric and Egidius, were amicably united against the common foe.

“THE ELDEST SON OF THE CHURCH” - DIVISIONS OF

GAUL.

We hasten to the reign of Clovis, who, during a rule of about thirty years,

not only united the various tribes of Franks under one powerful dynasty, and

founded a kingdom in Gaul on a broad and enduring basis, but made his throne

the centre of union to by far the greater

portion of the whole German race.

When Clovis succeeded his father as king of the Salians, at the early age

of fifteen, the extent of his territory and the number of his subjects were, as

we know, extremely small; at his death, he left to his successors a kingdom

more extensive than that of modern France.

The influence of the grateful partiality discernible in the works of

Catholic historians and chroniclers towards “the Eldest Son of the Church”, who

secured for them the victory over heathens on the one side, and heretics on the

other, prevents us from looking to them for an unbiassed estimate of

his character. Many of his crimes appeared to be committed in the cause of

Catholicity itself, and these they could hardly see in their proper light.

Pagans and Arians would have painted him in different colors; and had any of

their works come down to us, we might have sought the truth between the

positive of partiality and the negative of hatred. But fortunately, while the

chroniclers praise his actions in the highest terms, they tell us what those

actions were, and thus compel us to form a very different judgment from their

own. It would not be easy to extract from the pages of his greatest admirers

the slightest evidence of his possessing any qualities but those which are

necessary to a conqueror. In the hands of Providence he was an instrument of

the greatest good to the country he subdued, inasmuch as he freed it from the

curse of division into petty states, and furthered the spread of Christianity

in the very heart of Europe. But of any word or action that could make us

admire or love the man, there is not a single trace in history. His undeniable

courage is debased by a degree of cruelty unusual even in his times; and the

consummate skill and prudence, which did more to raise him to his high position

than even his military qualities, are rendered odious by the forms they take of

unscrupulous falsehood, meanness, cunning and hypocrisy.

It will add to the perspicuity of our brief narrative of the conquests of

Clovis, if we pause for a moment to consider the extent and situation of the

different portions into which Gaul was divided at his accession.

There were in all six independent states: 1st, that of the Salians; 2nd,

that of the Ripuarians; 3rd, that of the Visigoths; 4th, that of the Burgundians;

5th, the kingdom of Syagrius; and, 6th, Armorica (by which the whole sea-coast

between Seine and Loire was then signified). Of the two first we have already

spoken. The Visigoths held the whole of Southern Gaul. Their boundary to the

north was the river Loire, and to the east the Pagus Vellavus (Auvergne).

The boundary of the Burgundians on the side of Roman Gaul, was the Pagus Lingonicus (Upper

Marne); to the west they were bounded by the territory of the Visigoths, as

above described.

The territory still held by the Romans was divided into two parts, of which

the one was held by Syagrius, who, according to common opinion, only ruled the country

between Oise, Marne, and Seine; to this some writers have added Auxerre,

Troyes, and Orleans. The other — viz., that portion of Roman Gaul not subject

to Syagrius—is of uncertain extent. Armorica (Bretagne and Maine), was an

independent state, inhabited by Britons and Saxons; but what was its form of

government is not exactly known. It is important to bear these geographical

divisions in mind, because they coincide with the successive Frankish conquests

made under Clovis and his sons.

CLOVIS ATTACKS SYAGRIUS.

It would be unphilosophical to ascribe to Clovis a preconceived

plan of making himself master of these several independent states, and of not

only overthrowing the sole remaining pillar of the Roman Empire in Gaul, but,

what was far more difficult, of subduing other German tribes, as fierce and

independent, and in some cases more numerous than his own. In what he did, he

was merely gratifying a passion for the excitements of war and acquisition, and

that desire of expanding itself to its utmost limits, which is natural to every

active, powerful, and imperious mind. He must indeed have been more than

human to foresee, through all the obstacles that lay in his path, the career he

was destined by Providence to run. He was not even master of the whole Salian

tribe; and besides the Salians, there were other Franks on the Rhine, the

Scheldt, the Meuse, and the Moselle, in no way inferior to his own

subjects, and governed by kings of the same family as himself. Nor was

Syagrius, to whom the anomalous power of his father Egidius had

descended, a despicable foe. His merits, indeed, were rather those of an able

lawyer and a righteous judge than of a warrior; but he had acquired by his

civil virtues a reputation which made him an object of envy to Clovis, who

dreaded perhaps the permanent establishment of a Roman dynasty in Gaul. There

were reasons for attacking Syagrius first, which can hardly have escaped the

cunning of Clovis, and which doubtless guided him in the choice of his earliest

victim. The very integrity of the noble Roman’s character was one of these

reasons. Had Clovis commenced the work of destruction by attacking his kinsmen

Sigebert of Cologne and Ragnachar of

Cambrai, he would not only have received no aid from Syagrius in his

unrighteous aggression, but might have found him ready to oppose it. But

against Syagrius it was easy for Clovis to excite the national spirit of his

brother Franks, both in and out of his own territory. In such an expedition,

even had the kings declined to take an active part, he might reckon on crowds

of volunteers from every Frankish gau.

As soon therefore as he had emerged from the forced inactivity of extreme

youth (a period in which, fortunately for him, he was left undisturbed by his

less grasping and unscrupulous neighbors), he determined to bring the question

of pre-eminence between the Franks and Romans to as early an issue as possible.

Without waiting for a plausible ground of quarrel, he challenged Syagrius,

more Germanico, to the field, that their

respective fates might be determined by the God of Battles. Ragnachar of Cambrai was solicited to accompany his

treacherous relative on this expedition, and agreed to do so. Ghararich, another Frankish prince, whose alliance had been

looked for, preferred waiting until fortune had decided, with the prudent intention

of siding with the winner, and coming fresh into the field in time to spoil the

vanquished.

Syagrius was at Soissons, which he had inherited from his father, when

Clovis, with characteristic decision and rapidity, passed through the wood of

Ardennes, and fell upon him with resistless force. The Roman was completely

defeated, and the victor, having taken possession of Soissons, Rheims, and

other Roman towns in the Belgica Secunda, extended his frontier to the river Loire, the

boundary of the Visigoths. This battle took place in ad 486.

We know little or nothing of the materials of which the Roman army was

composed. If it consisted entirely of Gauls, accustomed to depend on Roman aid,

and destitute of the spirit of freemen, the ease with which Syagrius was

defeated will cause us less surprise. Having lost all in a single battle, the

unfortunate Roman fled for refuge to Toulouse, the court of Alaric, king of the

Visigoths, who basely yielded him to the threats of the youthful conqueror. But

one fate awaited those who stood in the way of Clovis: Syagrius was immediately

put to death, less in anger, than from the calculating policy which guided all

the movements of the Salian’s unfeeling heart.

During the next ten years after the death of Syagrius, there is less to

relate of Clovis than might be expected from the commencement of his career. We

cannot suppose that such a spirit was really at rest: he was probably nursing

his strength, and watching his opportunities; for, with all his impetuosity, he

was not a man to engage in an undertaking without good assurance of

success.

Almost the only expedition of this inactive period of his life, is one

recorded in a doubtful passage by Gregory of Tours, as having been made against

the Tongrians. This people lived in the ancient

country of the Eburones, on the Elbe, and had formerly been subjects of

his mother Basina. The Tongrians were

defeated, and their territory was, nominally at least, incorporated with the

kingdom of Clovis.

ALEMANNI DEFEATED AT ZÜLPICH -

CONVERSION OF CLOVIS.

In the year 496 A.D. the Salians began that career of conquest,

which they followed up with scarcely any intermission until the death of their

warrior king.

The Alemanni, extending themselves from their original seats on the right

bank of the Rhine, between the Main and the Danube, had pushed forward

into Germanica Prima, where they came into collision with the

Frankish subjects of King Sigebert of Cologne. Clovis flew to the assistance of

his kinsman, and defeated the Alemanni in a great battle in the neighborhood

of Zülpich. He then established a considerable

number of his Franks in the territory of the Alamanni, the traces of whose

residence are found in the names of Franconia and Frankfort.

The same year is rendered remarkable in ecclesiastical history by the

conversion of Clovis to Christianity. In AD 493, he had

married Clothildis, Chilperic the

king of Burgundy’s daughter, who, being herself a Christian, was naturally

anxious to turn away her warlike spouse from the rude faith of his forefathers.

The real result of her endeavors it is impossible to estimate, but, at all

events, she has not received from history the credit of success. The mere

suggestions of an affectionate wife would be considered as too simple and

prosaic a means of accounting for a change involving such mighty consequences.

The conversion of Clovis was so vitally important to the interests of the

Catholic Church, that the chroniclers of that wonder-loving age, profuse in the