AGE OF ATTILA

Fifth Century Byzantium and the Barbarians

BY

CHARLES DAVID GORDON

DURING THE FIFTH CENTURY the writing of contemporary history in the western

part of the Roman world was limited virtually to the compilation of meager

chronicles. In the East on the other hand, a sequence of historians

writing in Greek maintained the literary tradition of the Classical and

Hellenistic periods and consciously sought to link the present with the

past by adding to the works of their predecessors substantial narratives of

their own times. Thus, they recorded the death throes of the Western

Empire and the desperate yet in the end successful struggle for survival

by its Eastern counterpart.

Unfortunately, the remains of these fifth-century histories consist of

fragments of varying length preserved in works of writers of a later age.

Rut such as they are. they constitute an indispensable source for our

interpretation of the history of the critical period in which they were

written. Professor Gordon has made the bulk of the fragments available for the

first time in English translation. He has supplied an

introduction that facilitates their interpretation and linked them

together with short supplementary narratives in such a way as to present a

fairly continuous account of the outstanding military& and political

developments from the death of the Emperor Theodosius 1 in 395 to the

conquest of Italy by Theodoric the Ostrogoth in 493.

Since these fragments were preserved by later writers of the Eastern

Empire, who quoted them for various reasons, it is only natural that they

should be passages which deal for the most part with persons or episodes

that affected the East rather than the West. But this emphasis on the East

probably reflects the original character of the Greek histories of

the fifth century, for their authors wrote from the standpoint

of vii residents of the Eastern Empire and tended to treat at

greater length the happenings of which they bad more direct and more

detailed information. Events in the West seem to have been discussed in

proportion to their importance for the East, especially for the relations

existing between the two empires.

The theme which dominates the secular history of the period is the

struggle of the Romans against the barbarians—if we may use the latter term to

describe all of the foreign enemies of the two empires, even though many

of them had made considerable advances in civilization, particularly

under stimulus of their contacts with the Romans themselves. We see

both empires beset from within as well as from without. Along their

northern frontiers from Britain to the Caucasus tribes were poised for

assault upon the imperial defenses whenever the slightest hope of being

able to break through appeared. Within the frontier line of defense were

other peoples who had settled there with Roman assent as autonomous

military allies supported by Roman subsidies, but whose rulers sought to

win better lands and ever greater independence for their followers at the

expense of their nominal overlords. In addition, there were both individuals

and sizable bands under their own chiefs enrolled in the imperial armies—for

the most part composed of barbarian mercenaries, many of whom held the

highest military commands under the emperors and only too often sought to

take over control of the government. The historians do not disguise the

fact that the empires depended for their existence upon

barbarian arms and that their main problem was how to make use of and

at the same time control their mercenaries and allies.

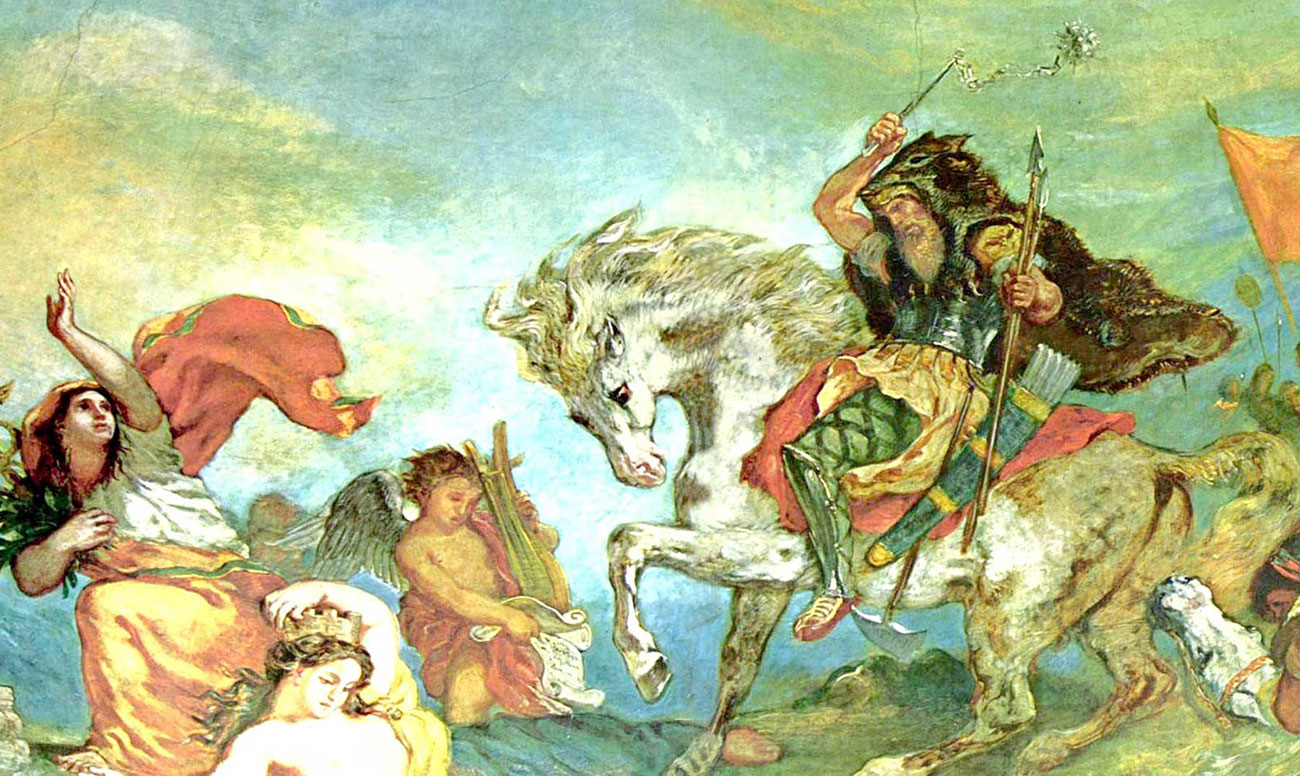

Although most of these barbarians were of Teutonic origin, potentially

the greatest menace to East and West alike during the earlier and middle parts

of the fifth century came from tire Huns, particularly when they were

firmly united under the rule of Attila (445-53). These terrible warriors

not only drove other barbarians to seek refuge within the empires and

forced still others to follow them in their attacks upon the Romans, but

they themselves raided far and wide on Roman territory and imposed crushing

tribute on the West as well as on the East. And yet we find bands of Huns

serving as mercenaries under the Roman standards. In one of the lengthier

fragments we have a vividly drawn picture of Attila at the height of his

power—and of the barbaric splendor in which he lived—from the pen of the

historian and official Priscus, who visited him as a member of an embassy

sent by the Eastern emperor, Theodosius II. From Priscus and other

writers one gains the impression that on various occasions

Attila could have overrun either or both empires had he pressed

his attacks against them. That he refrained seems to have been due

partly to a wish to preserve such a rich source of tribute in gold, partly

to a mistrust of the influence of the civilized urban life led by those

whom he considered to be his military inferiors. His sudden death in 453

was a factor of major importance in the survival of the empire in the East.

Against the background of the barbarian pressure these historians

describe a condition of almost incredible weakness and confusion in the

imperial governments themselves. We see weak and incompetent emperors,

dominated by corrupt and ambitious favorites, unable to distinguish

between useful and ruinous policies, rewarding loyalty with treachery,

success with assassination. The palaces are hotbeds of intrigue—ministers

against generals, members of each service against their colleagues, with

palace eunuchs playing a sinister role. Honest and efficient public

servants are so rare as to be singled out for exceptional praise.

Standards of public conduct certainly had not improved with the

Christianizing of the empire. Little is said directly of economic conditions,

but the huge sums of gold paid by the Eastern Empire as tribute to

the Huns arc faithfully recorded, and we are told of the ruin of many

persons under the heavy exactions of avaricious finance ministers. And the

defense which Priscus offers of the administration of justice in the East is by

no means as convincing to modem ears as he claims that it was to a Roman

refugee living among the Huns.

The fragments have a dramatic quality because they deal with the great

personalities whose aims and actions were determining the course of events.

Foremost among these are the three outstanding barbarian chieftains:

Alaric the Visigoth, Attila the Hun, and Theodoric the Ostrogoth, with

whom we should perhaps associate Gaiseric the Vandal. Others

also, although somewhat less prominent, played roles of great

significance. Such were the barbarians Stilicho and Ricimer, the Romans

Constantius and Aetius, and even the grand chamberlains Eutropius and

Chrysaphius. We see, too, the influential part taken in public affairs by women

of the imperial households, for example, by the much-married Galla

Placidia in the West and by the Empress Pulcheria and the

intriguing Verina in the East.

One looks in vain for any discussion of the reasons for the fall of the

empire in the West or the survival of its Eastern counterpart. But for the

first, the factual narrative is self-explanatory. An inept military policy,

ineffectual rulers, a lack of native military manpower, all in the face of

unceasing barbarian attacks, made the collapse inevitable. As for

the East, we see that the extinction of the dynasty of Theodosius the

Great gave an opportunity for the appointment of a series of forceful

energetic emperors, that a source of military strength with which to combat

the Teutonic mercenaries was found within the Empire, that two indomitable

foes, Alaric and Theodoric, were diverted from the East to the West,

and that the capital of the Empire in the East,

Constantinople, proved an impregnable refuge and base for military

operations. All these factors were of prime importance for the survival

of the East. Yet chance, too, played its part in the

providential death of the most formidable of the enemies of the

Empire, Attila the Hun.

Preface

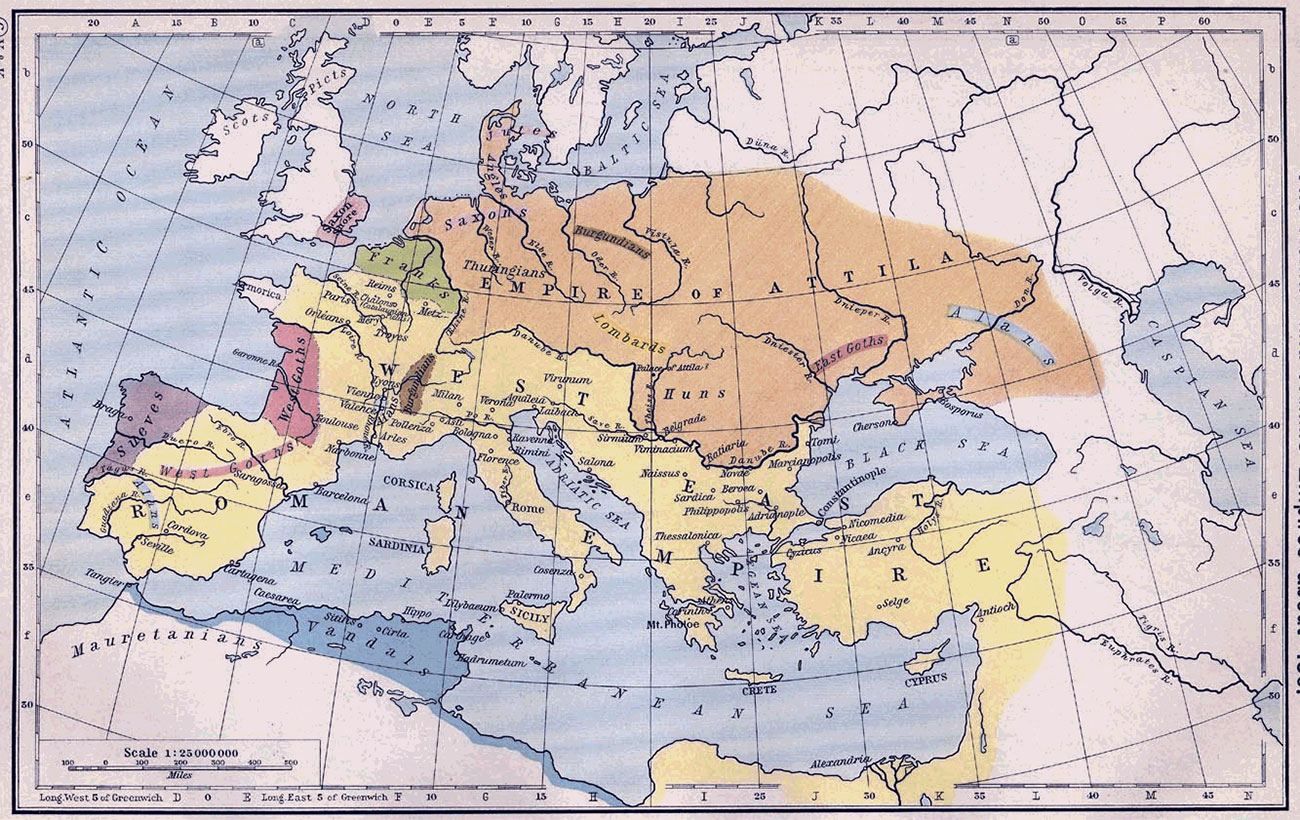

THE FIFTH CENTURY of our era saw far-reaching political changes in the

Mediterranean world. When the century began the Roman Empire controlled

directly very nearly the whole area it had dominated at its widest extent,

and, though under two rulers, was still a single entity from Yorkshire to the

Upper Nile and from Portugal to the Caucasus. When the century ended all

western Europe and western Africa were under the control of more or less

independent Teutonic kings. Many thousands of these Teutons had been

settled in restless semidependence within the

empire before 400, and after 500 many of their kingdoms were still

nominally held at the discretion of the ruler of Constantinople—Africa,

Italy, and parts of Spain were even subsequently brought for a

time again under direct Roman rule by Justinian in the sixth century.

Nevertheless, the western regions of the empire were in this century very

largely permanently alienated from the dominions which the Roman emperor could

say he really ruled.

It is a great loss that not one competent contemporary historian for the

period has been preserved intact. As a result the modem investigator is forced

to rely on ecclesiastical historians of dubious veracity who only

incidentally mention secular affairs, on very sketchy chroniclers, many of

them of a later date, on a subsidiary literature primarily nonhistorical,

and on tantalizing fragments of historical writings the chief part

of which has been long lost.

The dearth of adequate source material and the virtual absence of any

source material whatever with pretentions to literary merit have long

turned historians away from this century. Certainly, the writings of Julian the

Apostate and Ammianus in the fourth century and of Procopius and

Justinian’s legal works in the sixth have attracted scholarship

toward their centuries to the comparative neglect of the fifth.

Furthermore, the spectacle of decay and defeat which this

century xi presents is not one that has appealed to ages prior to our

own —which in many respects is better able than most to understand the

spirit of the fifth century.

But today the rapid decline in the knowledge of Latin and Greek has cut

off even the educated reader from this fascinating period, so similar to our

own. He must rely on such epitomes as general histories provide—and even

they are not so common as they might be—or on learned works based

on authors he cannot check. To remedy this to a slight extent the

translations on which this book is based give the reader with little or no

Greek, a chance to see for himself how the writers nearest to the events

described their age and its momentous tragedies. With very few exceptions all

the passages here translated have, to the best of my knowledge, never

appeared in full in English or any other modern language, though

paraphrases and summaries of most of them are, of course, included in

general histories of the period.

I have tried to tell the story of this tragic period as nearly as

possible in the words of contemporary or near contemporary authors,

linking the pitiful fragments of history left to us by only such

connective and introductory material from many scattered sources of less

general interest as seemed necessary to give a coherent and complete

narrative. The choice of authors I have translated is fairly obvious considering

the custom of that age of one historian continuing the work of his

predecessor. In that way Olympiodorus, Priscus, and Malchus overlap very little and together give a continuous history of most of the

century. To them I have added the short summary of Candidus which throws

additional light on the court history of Leo's and Zeno's reigns. All

these men were more or less contemporaries of the events they describe,

but the last author, Joannes Antiochenus, lived

considerably later and my excuse for including the excerpts from his work

pertaining to the years from 408-91 is that, as most scholars agree, he

made wide use of the other authors, often indeed, it seems, copying them

verbatim. Thus his work probably contains more extracts from Priscus, Malchus, and Candidus than are printed with those

authors’ known remains.

The best-known and most studied aspect of fifth-century civilization is

that concerned with religion and church affairs. For that reason I have virtually

ignored these matters, not because they were unimportant but because being

well publicized they do not need further elucidation in a book

primarily concerned with the interplay of barbarian and Roman.

And the ecclesiastical writers, historians and others, are in

most cases readily available in English translations. For the

same reasons this book also ignores most other aspects of life

in this period—economics, private life, the arts,

constitutional problems, law, and so on—except insofar as they impinge

on the history of the courts and the dealings with the barbarians. I

use the word barbarian rather loosely perhaps, as including all whom a

civilized native of Constantinople would so consider and name. Most of them, of

course, were invaders from beyond the frontiers, but the wild Isaurian

mountaineers may also, I hope, be included in the term without undue

criticism.

The chronological table is not designed for completeness nor to give a

chart of the historical forces at work in this century, but to show the

framework within which the events described are to be found; for this

reason little reference is made to religious or social events.

1.

Imperial Government

2. The

Dynasty of Theodosius I and the

Barbarians in the West

3. The Huns

4. The Vandals and the Collapse

of the West

5. The East, 450-91

6. The Ostrogoths

GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES

Chronological Table of the Fifth Century

(The names of emperors are in capitals)

395 Theodosius I died, Honorius emperor of the West (395-423) and

Arcadius emperor of the East (395408)

408 Theodosius II (the Younger) became emperor in Constantinople. He

ruled until 450

410 Rome captured by the Visigoth Alaric

412 Visigoths settled in Gaul

422 Minor war with Persia

423-25 Joannes usurper in the West; overthrown by Aspar and Ardaburius

425 Valentinian III became emperor of the West. Placidia regent (425-37)

429 Vandals, who had entered the empire in 406 and settled in Spain,

crossed to Africa under Gaiseric (427-77)

433 Attila became ling of the Huns, and Aetius returned as a power in

the Western Empire

441 War with Persia quickly settled in the face of Attila's first

serious invasion or the Eastern Empire

447

Second invasion by Attila

448

Embassy of Maximinus and Priscus to Attila

450

Theodosius II died; Marcian became emperor

451

Battle of Chalons; Attila repulsed from Gaul. Council of Calchedon

452

Attila invaded and devastated northern Italy and retired

453

Death of Attila

454

Aetius assassinated. Attila’s empire broken up after the battle of Nedao with Goths and others

455

Valentinian III assassinated; Maximus emperor; Rome sacked by Vandals,

maximus overthrown and replaced by Avitus (455-56) as emperor of the West.

Ricimer became a great power in the West

457 Marcian succeeded by Leo I in

the East. Aspar became a great power at Constantinople, Majorian came to the

western throne and reigned 457-61. Failure of expedition against Gaiseric

461-65 Severus emperor of the West 467-72 Anthemius emperor of the West

468 Great combined expedition against Gaiseric failed

471

Aspar overthrown in the East. Theodoric the Ostrogoth began to be a

threat to the East

472

Ricimer died

472-73 Olybrus emperor of the West

473-74 Clycerius emperor of the West

474 Leo died; succeeded by Zeno the Isaurian (474-91)

473-

78 Nepos emperor of the West, ending his reign in Dalmatia

474-

76 Romulus Augustulus last emperor of the West

475-

76 Revolt of Basiliscus in the East, reigned 20 months as usurper

476 Odovacar became king in Italy 484-88 Revolt of Ulus in the East

493 Theodoric having left the East in 488 became king in Italy

Imperial

Government

THEODOSIUS THE GREAT died early in 395, the last ruler of a united Roman

Empire—as great in extent as that left by Augustus. His two sons divided

the empire between them, Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West,

and never again did a single government control the

whole Mediterranean world. For centuries two languages had divided this

world and more recently the stagnation of trade, preoccupation with

differing threats on opposite frontiers, and religious disputes had

intensified the division. Though in the minds of contemporaries there

still existed a single monolithic oecumene with

twin capitals, to all intents and purposes the historian now has to deal

with two separate nations, closely related to one another by historical

tics and even, in the upper ranks of government for a few generations, by

family ties, but each generally concerned exclusively with its own pressing

internal and external problems and going its own way politically. It is not

surprising, therefore, to find in the history of the fifth century, the

Eastern Empire diverting barbarian threats from itself

westward against its sister empire and seldom lifting a finger to

help in the defense of the West in its dying agonies.

To understand how the courts at Constantinople and in Italy faced the

crisis of the fifth century—the barbarian attack from the north—a general

picture of the government and military machinery is necessary.

Christianity had achieved its final triumph with Theodosius so that the

emperor besides his supreme temporal power was henceforth also the sacred

representative of Christ on earth and as such in a very special way

divorced from ordinary mankind. His palace and everything about him

was “sacred”; those who approached him had to kneel in reverence, his

person was holy, and he was addressed as Dominus, Lord. He was supreme commander of all

the armies and, though in theory subject to the dictates of the traditional law

and the Church, in practice he was able to change or amplify the law by

edict and to control the bishops of the Church.

And yet he was still, as under the principate, an elected official; this

was no hereditary monarchy. In practice, of course, the ruler chose his

successor by associating him in the supreme power with the titles of

Augustus or Caesar, and the senate and army and, later, the Church merely

ratified this choice at inauguration ceremonies. The choice usually fell

to the ruler’s son, if any, or to a relative by blood or marriage. The

army had the final say on who should rule and for how long, as is shown by

the frequency of military backing for usurpers in this period; but it is

also noticeable that most would-be usurpers were connections of the

man they were trying to supersede.

In order to enhance the awe of the population and escape the buffetings

of misfortune and blame, the emperors made themselves somewhat mysterious

figures, hidden behind the palace walls, inaccessible and remote, and

shielded from the public by innumerable bureaucrats and palace officials.

The senate had become a largely hereditary and purely honorary body of

nobles, a sort of House of Lords, without real power, but its members were

highly respected and by virtue of individual offices frequently very

powerful. For the sons of senators the praetorship was the indispensable

office through which admittance to the senate was gained.

The praetors’ only duty was the exhibition of games or construction of public

works—frequently very heavy financial burdens. Eight praetors were chosen by

the senate each year. Higher officials of the bureaucracy, often men who

had worked their way up from humble origins, could also be named to the

senate without the burden of the praetorship being required by the emperor.

If the senatorship was largely a mere honor so

also were a series of other titles of rank. The consulship was still

the supreme dignity; a consul’s duties were similar to those of the

praetors, but financially he was often helped by the state. Besides the

two regular consuls each year not infrequently a consul suffectus would be named, a man who received

the title and rank without the actual office. Next to men of consular

rank came the patricians, who had no office or function at all. They were

men who, for outstanding services to the state, had been raised to this

high dignity by the emperor. The titles of illustris,

spectabilis, and clarissimus,

in descending order, were also purely honorary, but, at least by the

end of the fifth century, all holders of these titles were classed as

senators, though only the illustres could

actually take part in the deliberations of the senate. Nobilissimus

was a more restricted title, confined to the royal family. It

was lower than the designation of Caesar and temporarily dropped out

of use during the fifth century.

More powerful than the senate in the government was the consistorium or Imperial Council which was

constantly called on by the ruler for advice. The quaestor presided

over this council, which included the financial ministers, the master

of offices, the resident praetorian prefect and masters of soldiers, and

probably other high officials, assisted by a large body of secretaries and

clerks.

The supreme legal minister (the quaestor sacri palatii) drafted the laws and imperial answers to

petitions and generally supervised the emperor’s business.

The important and powerful master of offices (magister officiorum)

supervised several rather diverse departments in the civil service and the

palace. Separate masters of bureaus reported directly to the emperor from

the separate secretarial bureaus (scrinia), but the master of offices

himself controlled and supplied these bureaus. He was responsible for

court ceremonial, the general supervision of foreign affairs and the reception

of foreign ambassadors, the imperial post system (cursus publicus), and the secret service (the schola of agentes in rebus), these last—also called magistriani from the head of the department

controlling them— acted as couriers or messengers for confidential

business as well as spies on other officials in the capital and in

the provinces. The master of offices also supervised state arsenals and

had some control over frontier military commanders, but the imperial

bodyguards—the scholae palatii—were

the only force directly subject to him. They were divided into seven

cohorts or scholae (five in the West) stationed in and around the capital

and commanded by officers of the rank of count (comes).

There were two chief financial ministers each with his own staff, but

the exact division of their responsibilities, remembering the emperor’s

all-embracing power, is hard to define. These were the minister of finance

(comes sacrarum largitionum)

who supervised the raising of taxes and other revenues, government

monopolies and factories, and the mints; and a sort of minister of the

privy purse (the comes rerum privatarum)

who managed all imperial funds, imperial lands, and the personal and crown

property of the emperor.

So far we have been dealing with civil officials who helped manage the

affairs of the empire as a whole, but there was also a huge body of

officials concerned, at least in theory, with the management of the palace

itself. At the head of this body was a grand chamberlain, usually a

eunuch, known as the praepositus sacri cubiculi. With his

subordinates he controlled the palace servants and attendants and even

the imperial estates and so, coming into closer personal contact with

both the emperor and empress than any other official, frequently wielded

enormous power. As a eunuch he was almost invariably despised, but, as a

man having the sovereign’s ear, also widely feared and courted. The

relationships of this man with his fellow chamberlains (the primicerius sacri cubiculi, the castrensis sacri cubiculi—in control of palace servants—and comes sacrae vestis—in charge

of the royal wardrobe) are very uncertain. Indeed, at times the exact

position of historical figures is indefinite from the Greek habit of

translating the titles by phrases like “sword bearer” or “bed chamber

attendants.” It has been suggested for instance that the very powerful

Rasputin-like Chrysaphius, Theodosius II’s chamberlain, was not a praepositus but a primicerius with the functions of a bodyguard (or spatharius,

from the Greek word spatha, a “broadsword”).The primicerius was probably independent of the praepositus and the others his subordinates;

certainly the thirty ushers (silentiarii)

who formed the guard of honor in the palace were controlled by him. Often

the empress had her own chamberlain (praepositus).

All higher officers of the civil service or palace staff as well as all

military officers both in the capital and in the provinces were issued, on

appointment, a diploma drawn up by a chief personnel officer (the primicerius notariorum), who

noted the exact precedence each had in the complex hierarchy of honors and

dignity at court.

So much for the central government. The empire was divided into four

large prefectures: of the Gauls, of Italy, of Illyricum, and of the

East—the first two subject to the Western and the last two to the Eastern

emperor. Each prefecture was under a praetorian prefect, of whom the prefects

of Italy and the East were the highest ranking officials in the empire and

were sometimes referred to as praesens,

attending the emperor himself. A prefect issued edicts concerning his

prefecture, supervised its finances, coinage, and grain supply, and acted

as administrator of justice—assisted in this last duty by a legal adviser

called an assessor. The prefectures were divided into dioceses under vicarii, and these were subdivided into

provinces each under a governor—variously referred to as praeses, proconsul, or procurator. These

officials were not infrequently recruited from among men of humble origins

in the civil service, and we hear of men from the secret

service rising to a provincial governorship.

The cities of Rome and Constantinople were not under the jurisdiction of

any praetorian prefect, but each had a prefect of the city (praefectus urbanus).

He was head of the senate and his functions were purely civil; he was

chief criminal judge, police commissioner, and in charge of the water

supply and the provisioning of the city.

One of the great contrasts between the government of the Autocracy and

the Principate was the separation of military and civilian authority.

There were exceptions to this rule, as in Isauria, at times in Egypt, and

in the capital with regard to certain forces of bodyguards, but the

two branches were usually kept strictly apart. The armed forces at

this time consisted of two classes of troops, a mobile field army for use

on any threatened border or against any internal trouble, and garrison troops

permanently stationed on the frontiers. In the East the armies were

commanded by five masters of soldiers (magistri militum). Two of these (magistri militum praesentales,

or in praesenti) attended the emperor at Constantinople and had

precedence over the others who were in charge of the large military

districts of Thrace, Illyricum, and the East (Orientis). Under

these were counts (comites) in charge of

the local field forces and dukes (duces) in charge of the frontier

garrison troops. In the West the system was somewhat different. There

the armies were divided between two masters in praesenti, one in

charge of the cavalry (equitum) and the other

of the foot soldiers (peditum). Very

frequently, however, the master of infantry was made the superior of his

brother general by being given supreme charge of both branches with

the title of master of both services (magister utriusque militiae) or simply master of soldiers. The counts

and dukes in the West had positions similar to those in the East.

Apart from these forces there were various kinds of bodyguards stationed

in the capitals. We have already seen the scholae under the master of offices,

but in addition to these there were the candidati,

who also were in close attendance on the emperor, and the domestici. These last were both horse and foot

and while usually stationed at the court could be sent elsewhere. They

were under the command of a count of domestics (comes domesticorum) who was independent of the master of

soldiers and probably subject to the minister of the privy purse (comes

rerum privatarum). In any case we find them at

times apparently being used to collect taxes, which shows a connection

with a financial officer. The palatini, in spite of their name, were

not in any sense a part of the bodyguard at the capital, but merely an

elite corps forming a privileged part of the field forces kept closer to

the capitals than other troops.

One difficulty in identifying such officials, civil and military alike,

is the frequent vagueness and avoidance of the correct Latin designation

of which almost all Byzantine historians are guilty. In addition many

military titles like count (comes) or even master (magister)

were conferred as honorary titles on foreign leaders to win their respect

or loyalty, but without always implying specific duties.

The masters of soldiers were obviously men of very great power and

corresponding rank at court, and it is striking to find at this time so

many of them of foreign, usually German, extraction. The “foreignization”

of the armies had been going on for a long time, but the preponderance

of Germanic influence dates particularly from the time of Constantine

the Great in the first quarter of the fourth century. Many German

tribesmen were enrolled in the regular armies of the empires, and whole

tribes were also enlisted under their own chieftain (phylarch).

These were the so-called foederati, a term which was always

rather vague and ambiguous. The chief of an allied tribe received an

annual sum of money supposed to be the pay for the troops he commanded,

but payments to tribes beyond the frontier as bribes to purchase immunity

from attack had the same name (annonae) as payments to the tribes

settled within the empire, and it was only a face saving gesture

to call them foederati—allies in the hue sense. During the fifth

century the term foederati also came to be applied to miscellaneous

foreign mercenaries commanded by Roman officers and forming a distinct

section of the imperial forces. The name “bucellarius,”

in the days of Honorius,

was applied

not only to the Roman soldiers but also to certain Goths. Also the name

“foederati” was applied to a diverse and heterogeneous corps. The historian says dry bread was called “bucellaton"

and so supplies a comic nickname to the soldiers, since from this they are

called “bucellarii.”

The only important exception to the almost complete dominance of the

military service by Germanic troops and generals was the employment of

Isaurians in the latter half of the century as a counterpoise to them. This

people from the backward and still almost barbaric southern

interior of Asia Minor, almost alone of the old peoples of the

empire, could still furnish large numbers of warlike and

efficient soldiers when called on to do so. Because of them

the Eastern Empire did not have to rely so heavily on the Germans and

as a partial consequence escaped the fate of the West.

In subsequent chapters we shall see how the empire dealt with the major

threats from across the Rhine and Danube; the scanty references to the much

less important threats on other frontiers may be briefly collected here.

The nation foremost in Byzantine eyes for the longest time was undoubtedly

the empire of Persia or, as they often called it erroneously, Parthia. In

contrast to other eras the relationship between the two empires in this century

was remarkably free from conflict, probably because both were too

preoccupied with other threats to trouble each other. Certainly, tire Huns

were a common danger for many years. There was a brief outbreak of

hostilities in 422 and again in 441, both almost immediately patched up,

and the Romans in most years continued a fourth-century agreement by

which they paid a fixed sum annually to the Persians, ostensibly to

help in the defense of the Caspian Gates against the Huns. Though several

incidents occurred that might have led to hostilities all were quickly

smoothed over.

About 464 when Perozes was reigning in Persia (453-82) an embassy came

from the monarch of the Persians with an accusation concerning men of his nation

who were fleeing to the Romans and concerning the Magi. These were

Persians of the priestly class who

from ancient times had dwelt in the land of the Romans, particularly in

the province of Cappadocia. They asserted that the Romans desired to keep the

Magi from their native customs and laws and from the holy rites of their

deity, that they constantly troubled them, and that they did not

allow the fire, which they call unquenchable, to burn according

to their law. The Persian religion was a form of Sun or Fire worship

and Mazda was a sun god. Further, they said, the Romans, by supplying

money, ought to give attention to the fortress of Iouroeipaach situated at the Caspian Gates, or else ought to send soldiers to guard it.

It was not right that Persians alone should be burdened with the

expense and with the guarding of the place. If the Romans did

not give help the outrages of the races dwelling roundabout would easily

fall not only on the Persians but also on the Romans. It was fitting, they

said, that the Romans should help with money in the war against the Huns,

who were called Kidarites, or Ephthalites, since

they would have the advantages if the Persians were triumphant, in that

the nation would not be allowed even to cross into the Roman dominion.

The Romans answered that they would send someone to confer with the

Parthian monarch concerning these points. They

said that there were no fugitives among them nor had they troubled the

Magi about their religion. And as for guarding the fortress of Iouroeipaach and the war against the Huns, since the

Persians had undertaken these on their own behalf, they did not justly

demand money from them ... Constantius was sent to the Persians. He had

attained the dignity of a third prefecture and in addition to consular

rank had obtained patrician honors.

Constantius remained at Edessa, a Roman city

on the border of the land of the Persians, since the Parthian monarch for a

long time continual postponed admitting him.

After Constantius, the envoy, had waited a time on his embassy in Edessa,

as was told, the monarch of the Persians received him into his country and

ordered him to come to him while he was busy, not in the cities,

but on the borders between his country and that of the Kidarite Huns.

He was engaged in war with them on the pretext that the Huns had not

brought the tribute which the former rulers of the Persians and Parthians

had imposed. Perozes’ father, Isdigerdes, had

been refused the payment of the tributes and had resorted to war. This war

he had passed to his son along with the kingship, so that the Persians,

being worn out with fighting, desired to resolve the differences with

the Huns by treachery. So Perozes, for this was the name of the ruler of the

Persians, sent to Kunchas, the leader of the

Huns, saying that he would gladly make peace with him, and wished to

conclude a treaty of alliance, and would betroth his sister to him, for it

happened that he was very young and not yet the father of children.

When Kunchas had received these proposals

favorably he married, not the sister of Perozes, but another woman adorned

in royal fashion. The monarch of the Persians had sent this woman and

promised that she would share in royal honors and prosperity

if she revealed nothing of these arrangements, but that if she did tell of

the deceit she would pay the death penalty. The ruler of the Kidarites, he

said, would not stand having a maidservant for a wife in place of a nobly

born woman. Perozes having made a treaty on these conditions did not long enjoy

his treachery against the ruler of the Huns. The woman, since she feared

that sometime the ruler of the race would learn from others what her

fortune was and submit her to a cruel death, revealed what had been

practiced on him. Kunchas praised the woman for

her honesty and continued to keep her as his wife, but wishing to punish

Perozes for his trick, he pretended to have a war against his neighbors

and to need men—not soldiers suited for battle, for he had an

infinite number of these—who would prosecute the war as generals for

him. Perozes sent three hundred men to him from his elite corps. Some of

these the ruler of the Kidarites killed, and others he mutilated and sent

back to Perozes to announce that he had paid this penalty for his falsehood. So again war had

flamed up between them, and they were fighting obstinately. In Gorga,

therefore, for this was the name of the place where the Persians were

encamped, Perozes received Constantius. For several days he treated him kindly and

then dismissed him, having made no favorable answer concerning the

embassy.

In the eastern Black Sea area the land of the Christian Lazi was for long

a bone of contention. In the years 465-66 the Romans went to Colchis to war

against the Lazi, and then the Roman army packed

up for return to their own land. The emperor’s court prepared for another

right and held council whether they should carry on

the war by proceeding by the same route or the route through Armenia,

which bordered on the country of the Persians, first having won over the

monarch of the Parthians with an embassy. It was considered impracticable

for them to sail along the difficult lands by sea, since Colchis was harborless. Gobazes, the king of the Lazi,

sent an embassy to the Parthians and also one to the emperor of the

Romans. The monarch of the Parthians, since he was engaged in

war against the Huns, called Kidarites, threw out the Lazi who had fled to him. This monarch (monarchos as

distinct from basileus, the Roman emperor) was Perozes.

The Romans answered the envoys sent by Gobazes that they would cease from war if Gobazes hid aside his sovereignty or deprived his son of

his royalty, for it was not right, according to ancient custom, that

both should be rulers of the land. And so Euphemius proposed that either man should reign over Colchis, Gobazes or

his son, and that war be stopped there. He held the position of

master of offices and, having a reputation for intelligence and skill in

arguments, had had the management of the affairs of Emperor Marcian

assigned to him, and had been that ruler's guide in many good counsels. He

took Priscus the historian as a partner in the cares of his

command. When the choice was given him, Gobazes chose to withdraw from his

sovereignty in favor of his son, himself laying down the insignia of his rule. He sent men

to the ruler of the Romans to ask that, since a single man was now

ruling the Colchians, he should no longer in anger take up arms on

his account. The emperor ordered him to cross into the land of the Romans

and explain what seemed best to him. He did not refuse to come, but

demanded that the emperor should hand over Dionysius, a man who had

formerly been sent to Colchis because of disagreements with the same

Gobazes, as a pledge that he would suffer no serious harm. Whereupon

Dionysius was sent to Colchis, and they made an agreement regarding

their differences.

After the burning

of the city under Leo, Gobazes with

Dionysius came to Constantinople, wearing a Persian robe and attended by a

bodyguard in the Medic manner. Those who received him at the palace blamed him at first for his

rebellious attitude and then, showing him kindness, sent him away,

for he won them over by the flattery of his speeches and the symbols of

the Christians brought with him.

The Persians did not interfere in these Lazic affairs because they were almost constantly being attacked by the eastern

Hunnish tribes. For instance, about 467 the Saraguri,

having attacked the Akitiri and other

races, marched against the Persians. First they

came to the Caspian Gates, and, finding a Persian fortress established in

them, turned to another route. Through this they went

against the Iberians and ravaged their country and then overran the

lands of the Armenians. And so the Persians, who were alarmed at this

inroad on top of the old war with the Kidarites which was engaging their

attention, sent an embassy to the Romans and demanded money or men for

the defense of the fortress of Iouroeipaach.

They said—what had often been said by their ambassadors—that since

they were undertaking the fighting and were not allowing the oncoming

barbarian tribes to have admittance, the land of the Romans remained

unravaged. When they received the reply that each ought to fight for his

own territory and to care for his own fortress, they retired again with

nothing accomplished.

Other troubles arose from time to time because of other Caucasian races

who appealed now to the Romans and now to

the Persians and therefore came under the domination of now one and now

the other empire. Souannia and Iberia were two

of these petty principalities.

In 468 there was a very grave disagreement between the nation of the Souanni and the Romans and Lazi; the Souanni were fighting in particular against Serna,

leader of the Lazi under... Since the Persians

also wished to go to war with the king of the Souanni on account of the fortresses captured by them, he sent an embassy

demanding that auxiliaries be sent to him by the emperor from among the

soldiers guarding the frontiers of the Armenians who were tributary to the

Romans. Since these were nearby he would thus have a ready help and not be

in danger while waiting for those who were far off, nor be burdened by

the expense if they came in time. The war, as had happened before,

might be continually postponed if this should be done, for when aid had

been sent under Heracleius, the Persians and

Iberians who were at war with him were at that time embroiled with other

nations. So the Souannian king had dismissed the

allied force, being troubled about the supply of their provisions, but

when the Parthians returned against him again he recalled the Remans.

The Romans announced that

they would send help and a man to lead this force. Then an embassy came from

the Persians too, declaring that the Kidarite Huns had been conquered by them and that they had taken the city

of Balaam by siege. They disclosed this victory and boasted in

barbaric vein that they would willingly show foe mighty force which they

had. But the emperor at once dismissed them when their news had been

announced, since he considered the events in Sicily to be of greater concern.

In spite of the Persian king’s boast his troubles with

the Huns were not over. Perozes, foe king of the Persians, who reigned

after his father Isdigeides, lived sixty years

and died in the war against the neighboring Huns in January 484. After the

lapse of four years Cabades took the kingship,

but, by a plot of certain important officials, he too was removed from the

leadership and shut up in a fort. Escaping secretly, he reached the Huns

called Kadisenes and through their help again seized

the kingship and slew those who had plotted against him. These Kadisene Huns are probably the same or nearly allied

to the Kidarite and Ephthalite Huns. Cabades, or Kawad, reigned 488-97

and 499-531, and under him serious wars broke out again with the

Roman Empire of the East in the sixth century.

On the Syrian frontier the Saracens, sometimes referred to as Arabs,

were closely allied with the Persian problem. They were largely nomadic brigands

who for many years played the Persia ns off against the Romans to their

own advantage by offering their services to the rival empires

in turn, but their sporadic raids were not, in this century,

a serious threat at any time.

About 451 Ardaburius, the son of Aspar, was waging war at Damascus

against the Saracens. When Maximinus, the general, and Priscus, his secretary,

arrived there they found him negotiating for peace with

the ambassadors of the Saracens.

Ardaburius, a man of noble mind, had stoutly beaten off the barbarians

who often overran Thrace. The Emperor Marcian gave him the Eastern army

command as master of soldiers in the Fast as a reward for his valor. When

he had pacified this region the general turned to relaxation and effeminate

ease. He took pleasure in mimes and jugglers and all the delights of the

stage, and passed the whole day in such shameful pursuits, heedless of the

reputation his actions gave him.

Marcian was a good emperor, but he soon died (457), and Aspar, of his

own unhindered will, appointed Leo to be his successor.

In 473 again, in the seventeenth year of the reign of Leo the Butcher, so called because of his

ruthless destruction of Aspar and his family in 471,

everything seemed in complete and utter confusion. A certain Christian priest

among the tented Arabs, whom they called Saracens, arrived on the

following mission. The Persians and Romans had made a treaty in 422 when,

in Theodosius’ time, the great war had broken out between them, to the

effect that neither would accept the Saracens as allies if any of

them proposed to raise the standard of revolt.

Among the Persians was a certain Amorkesos [Amiru ’Kais] of the race of Nokalius. Either because he was

not attaining honor in the Persian land or for some other reason, he

thought the Roman Empire better, and, leaving Persia, he went to the part

of Arabia bordering on Persia. Advancing from there he made forays and wars,

not against any Romans but always against the Saracens he met. As he

advanced little by little his power increased by reason of these raids. He

seized an island belonging to the Romans, Jotabe by

name, and, throwing out the Roman tithe collectors, he held it himself,

seizing its tribute and gaining no little wealth from it.

Amorkesos seized other villages nearby and asked to become an ally of

the Romans and a commander of the Saracens under Roman rule against Persia. He sent Peter, a bishop

of his company, to Leo, the emperor of the Romans, to see if he could ever

gain his point by persuading the emperor of these matters. When Peter had

arrived and made his representations to the emperor, the latter accepted

his arguments and straightway sent for Amorkesos to come to him.

In this respect he acted very ill-advisedly, for if he intended to

appoint Amorkesos commander he ought to have made this

appointment while he was far away so that he might always appreciate the

might of the Romans and come submissively before any Roman commanders and

heed the greeting of the emperor. At a distance the emperor

would have seemed to be superior to other humans. Instead, he first

led him through cities which he would sec full of luxuriousness and

unaccustomed to arms. Then, when he reached Byzantium, he was readily

received before the emperor, who caused him to share the royal table and,

when the senate was meeting, had him join with that council. The most

shameful disgrace for the Romans was that the emperor, pretending to have

persuaded Amorkesos to become a Christian, ordered that he be seated with

precedence over the patricians. Finally, when he had privately received

a certain very valuable gold and mosaic picture, he dismissed him

having repaid him with money from the state funds and ordered

such of the others as were in the senate to bring him gifts. The emperor

not only left him firmly in possession of the island which I mentioned,

but also handed over to him many villages. By granting these

concessions to Amorkesos, and making him phylarch of the tribes

he had asked for, he sent him away a proud man, who was not going to

pay tribute to those who had made him welcome. The island was recovered in

498.

Once Diocletian had brought the tribes south of Egypt under Roman domination they remained

generally peaceful. They were people who stirred Roman curiosity. Early in

the century Olympiodorus the historian who came from this region wrote about

them. He says that while he was

living at Thebes and Syene for the sake of

investigating them, the chiefs and priests of Isis and Mandulis among the barbarians at Talmis (called Blemmyes)

wished to meet him, because of his reputation. “They took me,” he says,

“as far as Talmis itself so that I

might investigate those regions which are five days distant

from Philae, as far, indeed, as the city called Prima, which of old

was the first city of the Thebaid that one reached when coming from

barbarian territory. Hence it was called Prima by the Romans, that is ‘First’

in the Latin language; and even now it is still so named, although for a

long time it has been occupied by the barbarians, with four other

towns —Phoenico, Chiris, Thapis, and Talmis”—in

accordance with the arrangements of Diocletian which moved

the boundary northward. In these districts, he says, he learned that

there were emerald mines, from which the stone was supplied in abundance to the kings of

Egypt. “But these,” he says, “the priests of the barbarians forbade me to

see. Indeed, this was impossible to do without royal permission.”

The desert too remained a matter of wonder.

The same author tells many strange tales about the

Oasis and its fine atmosphere, and says that not only none there have

epilepsy—called the sacred sickness because in their fits the victims were

thought to be communing with the gods—but that those who come there are

freed from the disease on account of the fine quality of the air.

Concerning the vast extent of sand and the wells dug there, he

says that, having been dug to a depth of two hundred, three hundred,

or sometimes even five hundred cubits—300 to 730 feet—they gush forth in a

stream from the opening. The farmers who perform the community labor draw

water in turn from the wells, to water their native soil. The fruit

is always heavy on the trees, and the wheat, better there than any other

wheat and whiter than snow, and sometimes the barley too, is sown twice a

year, and the millet always three times. They water their fields

every third day in summer and every sixth day in winter, so that the fertility

is maintained. There are never clouds. He also tells about the water clocks

made by the natives. He says that [the Oasis] was formerly an island

separated from the mainland and that Herodotus calls it the Isles of

the Blessed.

Herodorus, who wrote a history of Orpheus and Musaeus, calls it Phaeacia. He

proves that it was an island both from the evidence of the discovery of

sea shells and the oysters molded in the stones of the mountains which stretch

from the Thebaid to the Oasis, and, second, because sand always pours

out and fills up the three Oases. (He says that there are three Oases, two

great ones, one further out in the desert and the other closer in,

situated opposite each other, about one hundred miles apart, and a third

smaller one separated by a great distance from the other two.) He

states as proof of its having been an island that fish are often seen

being carried by birds, and at other times the remains of fish, so it is conjectured that the sea is not far

from the place. He says that Homer derived Iris descent from the Thebaid

near this place. This was the oasis of El Kargeh, “seven

days’ journey from Egyptian Thebes” according to Herodotus’ approximately

correct estimate. The oasis of Ammon, modem Siwah,

was much farther away. The other great oasis is either Karafra north of El Kargeh or Dakhla to the west.

A brief rebellion broke out in 451 along the southern border, but was easily handled by the local

Roman official, Florus. The

Blemmyes and Nubaecs or Nobatae, having

been conquered by the Romans, sent ambassadors to Maximinus from both

their races to conclude a treaty of peace. They said they would keep the

peace conscientiously as long as Maximinus remained in the region of

Thebes. When he did not allow them to make peace for that length of

time, they said that they would not take up arms during his lifetime. When

he did not agree to the second proposals of the embassy either, they

proposed a hundred years’ treaty. In this treaty it was agreed that the

Roman captives should be freed without ransom whether they had been

captured in this or another attack, that cattle which had been

driven off should be handed back, that compensation should be paid

for those consumed, that nobly born hostages were to be given by them as

security for the truce, and that in accordance with an ancient law they were to

have unhindered admittance to the shrine of Isis, though the Egyptians

retained the care of the river boat in which the statue of the goddess was

placed and ferried across. At a specified time the barbarians carry the

image across to their own land, and having received oracles from it they bring

it back safe again to the island.

It seemed fitting to Maximinus, therefore, to settle

these agreements in the temple at Philae. Other men were sent for this

purpose, and those of the Blemmyes and Nubades who had proposed the treaty came to the island. When the agreements

were written down and the hostages handed over—these were from the ruling families

and the sons of rulers, a thing which had never before happened in

this war, for never had the sons of Nubades or

Blemmyes been hostages among the Romans—Maximinus became sick

and died. As soon as the barbarians learned of Maximinus’ death they

recovered the hostages, took them away, and overran the country.

These troubles on the frontier were intensified by more serious religious disturbances in

the capital. The local patriarch, Dioscorus, was removed from his see by

the Council of Chalcedon in October 451 for his Eutychian heresies, despite the

fact he had played a

leading part in the Council of Ephesus three years previously. Besides,

Dioscorus was condemned to live in the city of Gangra in

Paphlagonia, and Proterius was named bishop of

Alexandria by the common vote of the synod. When he occupied his appointed

throne a great tumult arose among the people who seethed in differences of

opinion. Some demanded Dioscorus, as is natural on such occasions,

and others more spiritedly clove to Proterius,

so that many irreparable troubles befell them. Priscus, the

rhetorician, writes in his history that at this time lie arrived at

Alexandria from the province of Thebes, and saw the mob advancing against the

governors. When a military force tried to stop the riot the people threw

stones. They put the troops to flight and besieged them, and when they

retired to the temple formerly devoted to Seraphis they burned them alive. When the emperor learned of these events he

dispatched two thousand newly enlisted troops, and with a fair

wind they landed in the great city of Alexandria on the sixth

day. Such a rapid journey was only possible with the Etesian winds of

July. Then, since the soldiers drunkenly abused the wives and daughters of

the Alexandrians, events much more terrible than before took place.

Finally, the mob, assembled in the Hippodrome, asked Florus,

the commander of the military forces and in charge of the civil

administration, to institute again the distribution of grain which he had

taken from them, and the baths and spectacles and whatever else he

had deprived them of on account of the disorders which had taken

place. And so Florus at the emperor’s suggestion

appeared before the people and promised to do this, and the rioting soon

stopped.

This flareup in Alexandria reminds us that in this century, at the very

time when the empire was being dangerously hard-pressed from the north it

was also having to face serious internal dissensions caused largely by

three separate things—religious factionalism, economic difficulties, and the

ambitions of unscrupulous and powerful figures at the courts. In the

fourth century the great religious dispute arose about the heresy of

Arianism, which denied that Christ was coeternal with the Father. Though this

doctrine was condemned at the Council of Nicaea in 325 and soon died

out in the empire, it had spread to the Germanic tribes and for two

centuries or more tended to increase friction between them and the

orthodox imperial courts. In the next centuries the important theological

disputes centered around the exact relationship of the humanity and

divinity in Christ, one faction tending to deny that Christ was

ever a real man and the other supporting the indissoluble combination of

the human and divine in him. Even among the latter group the exact formula

for expressing the union of the two natures of Christ caused many bitter

quarrels intensified by the rivalry for precedence of the

patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, and the pope

in Rome.

At Chalcedon in 451 the Fourth Ecumenical Council attempted to reconcile

the divergent views and though it agreed on a formula, it could not

reconcile the powerful bishops to one another nor the Eastern patriarchs

to beliefs largely dictated by the pope. Soon renewed conflict

arose led by the Monophysites in Egypt, who upheld the single nature

of Christ as opposed to the doctrine of two natures adopted at Chalcedon,

and the dispute, often accompanied by violence, spread throughout the East

in spite of vigorous persecution. Under the usurper Basiliscus it even

reached to the imperial throne itself. In 481 in a further attempt

to restore peace Zeno issued his Henotikon, a

letter to the church in Egypt, in which by ignoring the formula of Chalcedon he

sought to suggest that the Monophysites and their rivals could agree to

the older Nicaean Creed and forget their other differences. This dictation

to the Church by the Eastern emperor was, of course, not acceptable

to the pope; the Henotikon reconciled the

moderate Monophysites and secured ecclesiastical peace in the East

for thirty years but only at the cost of a schism with the West.

The economic difficulties faced by the courts were due to a complex

group of causes, manpower shortages, overtaxation,

ravishment of large areas by invasion or rebellion, payments of large

subsidies to enemies beyond the frontiers, and the enormous inequalities

of wealth. The whole coinage system of this period is full of

difficulties, but it is sufficient here to deal only with gold. After

Constantine’s reforms the standard Roman coin—variously called the solidus, aureus, nomisma, or simply “piece of gold”—-was valued

at 72 to the Roman pound or, since the Roman pound equaled .72 of a

modern pound, 100 to the modem pound. Gold in 1958 was $35.00 an ounce,

and with 12 ounces to the pound (Troy weight), a pound of gold was worth

$420. (The occasional use of the out-of-date "talent”

indicates about 5.8 pounds of gold.) Thus, a solidus would be

worth $4.20 in gold and a Roman pound $302.40. We also find frequent

mention of the centenarium, which was not a

coin but simply indicated 100 Roman pounds of gold or $30,240. The

ratio of gold to silver fluctuated between 1:14 to 1:18.

A more difficult question is the purchasing power of gold or the real

value in food, shelter, and so on of these sums. Bury has estimated that a

unit of gold in the fifth century would purchase thrice as much as in

1900. If that is true it would buy at least ten times as much as today. We

have little concrete evidence about prices in this period and what we

do have is conflicting or at least shows great variation in prices between

different periods and places and in different situations. Thompson points out

that eight solidi or about $33.60 would buy nearly 100 modii, 25 bushels,

of wheat which would amount to $1.34 per bushel. This seems rather high; a

few years later a solidus would buy 60 modii which would mean a price of $,28

per bushel. This is stated as a mark of the prosperity of Theodoric’s

kingdom in Italy, but what the farmers (in days before price support

programs) thought about this price we are not told. On the

other hand, in exceptional circumstances, probably when in 416 the

Goths and Vandals were both in Spain and the Goths were blockaded in Taragonne by the Romans to force them to peace terms,

there was runaway inflation.

The Vandals call the Goths Trouli, because,

crushed by hunger, the latter brought from the Vandals a trula of wheat for one aureus. The trula does not

hold a third of a sextarius. As a sextarius was less than a pint, there were

something like 200 trulae to a bushel,

and wheat brought the astounding amount of $840 a bushel.

Taxation, a subject that hardly concerns us here, fell very heavily on

ordinary people, especially the small farmers. The most arduous of their

burdens was a tax in kind (annona), originally

to supply the army but by this century also to support the huge

bureaucracy. This tax (annona militaris or to stratiotikon siteresion) might be called the Army

Food Stuffs Quota. That taxation did not fall heavily on the privileged

aristocracy, who could either evade it or pass it on to the tenants on their

estates, is borne out by references to huge fortunes.

Each of many Roman households received revenues of about forty centenaria of gold from their possessions, not counting the grain

and wine and all other goods in kind which, if sold, would have amounted to a

third of the gold brought in. The houses of the second class in

Rome, after the foremost ones, had revenues of ten or fifteen centenaria. Probus, the son of Olympius,

spent twelve centenaria of gold when exercising his

praetorship in the time of the usurper Joannes. Symmachus, the orator, a

senator of moderate wealth, before Rome was captured in 410 expended

twenty centenaria when his son Symmachus was

exercising the praetorship. Maximus, one of the wealthy men, laid out

forty centenaria for the praetorship of his son. The praetors used to celebrate the solemn festivals

for seven days. In fact the ancient capital of the empire still

gave as a whole an impression of wealth at the beginning of our period. Each of

the great houses of Rome had in itself everything that a moderate town could

have, a hippodrome, fora, temples, fountains, and divers baths; wherefore the

historian exclaims,

“One house a city is; the city hides ten thousand towns.” There were

also immense public baths. Those called the Baths of Antoninus, now the

Baths of Caracalla, had 1600 seats of polished marble for the use of the

bathers, and those of Diocletian had nearly double the number. The wall

of Rome, measured by Ammon the geometrician at the time the Goths

made their earlier attack on Rome, was shown to have a length of

twenty-one miles. Ammon made a mistake, though, for the walls of Aurelian,

repaired by Honorius at the time of Alaric’s attack in 408-10, were only

twelve miles long.

The third cause of internal trouble, revolts and rebellions on the part

of ambitious officials and the almost continuous court intrigues, will be

amply illustrated in the following chapters. It is enough to point out

here the fact that most of these troubles were inspired or carried out by

the powerful barbarian generals within the empire.

The Dynasty of Theodosius I and the Barbarians in the

West

THE reigns of Arcadius and Theodosius II in the Fast and of Honorius and

Valentinian III in the West span the whole first half of the fifth century,

but to imagine that the governments were in any real sense dominated by any of

these four weak monarchs during their respective reigns would be a

complete misreading of history. The real power at the courts was in the

hands of a succession of powerful ministers —many of Germanic origin—who

used it or abused it largely for their own ends and managed their nominal

masters by flattery and the courts by almost continuous intrigue.

Unlike their behavior in the later years of the century, these powerful

generals did not aim for the most part at setting up their own puppet

emperors but only at eliminating rivals of their own kind.

On the death of Theodosius the Great the first such struggle occurred

between Rufinus, a Gaul, at that time praetorian prefect of the East, and

Stilicho, a man of Vandal extraction who had been comes domesticorum, magister militum praesentalis, and magister utriusque militiae in Italy. Stilicho had married

Serena the niece of Theodosius, who left his young sons under his

unofficial protection.

Concerning Stilicho, Olympiodorus tells what great power he

attained—appointed guardian of the children, Arcadius and Honorius, by their

father Theodosius the Great—and how he married Serena when

Theodosius betrothed her to him. After this Stilicho made the

Emperor Honorius his son-in-law, as husband first of his

daughter Maria and, after her death in 408, of his other daughter, Thermantia, and so was raised even further to the highest

pitch of power. He successfully waged many wars for the Romans against

many tribes. Finally, by the murderous and inhuman avidity of Olympius, whom he himself had introduced to the emperor, he

met his death by the sword.

This man, nominally only a general of the Western armies, was in fact

the chief military figure of both empires, and before the year of

Theodosius’ death was out he had secured the murder of his Eastern rival

Rufinus. But he came into renewed and continued conflict with the

Eastern court over which empire should control Illyricum, the

most valuable reservoir of military manpower in either empire at this

period. Stilicho naturally tried to bring it under his jurisdiction in the

West and so made enemies for himself in the East

Arcadius, a youth of seventeen or eighteen on coming to supreme power in

Constantinople, was a feeble-minded and ineffectual ruler easily dominated

by strong personalities at the court. Hence his reliance first was on

Rufinus, then briefly on Stilicho, then on Gainas, the leader of

Ostrogothic forces, and in civil affairs on the eunuch Eutropius. Gainas was

particularly dangerous to the security of the state and, after he had

destroyed Eutropius, the Huns under Uldin and German troops under the Goth Fravitta eventually had to be called in to destroy him. Meanwhile, the Eastern

Empire was ravished by the Visigoths under Alaric in the Balkan lands

and by a wild Hunnish invasion from the East. By 400 the Germanic danger

to the East had been temporarily removed, only to be followed by a series

of even more violent conflicts between the Empress Eudoxia and John

Chrysostom, the patriarch of Constantinople, and by serious troubles with

Isaurian brigands in the southern part of Asia Minor. The chief power of

the government was in the hands of Anthemius, the praetorian prefect of

the East.

When Arcadius died in 408 he left a young son of seven to succeed him as

Theodosius II, but for six years the government was in the capable hands of

Anthemius as regent. In 414 Pulcheria, Theodosius’ elder sister and a

woman of decisive and vigorous character destined to dominate the

court for nearly half a century, was proclaimed Augusta and took over

the reins of government in the name of her brother. On

account of his extreme youth Theodosius was not able to make decisions or

to wage war. He wrote his signature for those who desired it—especially

for the eunuchs of the palace by whom everyone was being ravaged of

his possessions, so to speak. Some while still living made over their

property, and some sent their wives to other men and had their children forcibly

taken from them, being unable to oppose the commandments of the emperor.

The Roman state was in the hands of these men. The chief of

these eunuchs was Antiochus, who had great power as tutor to

the young emperor until he was removed by Pulcheria.

We have two brief descriptions of Theodosius as a young man. The Emperor

Theodosius, saying that he enjoyed their

pleasures, turned his mind toward liberal books, and to Paulinus and Placitus, who read them with him, he freely granted

great offices and wealth. Because he was shut up in the palace,

he grew to no great size; he became so thoughtful that he used to make trial of

many matters with those he met and was so patient that he could endure nobly cold and burning heat. His

forbearance and friendliness conquered all men, so to speak. The Emperor

Julian, although proclaiming himself a philosopher, did not bear anger

against the Antiochenes who had approved of him but did torture Theodorus. Theodosius, on the other hand, proclaiming that

he enjoyed the syllogisms of Aristotle, practiced his philosophy in

action and wholly put aside anger, violence, grief, pleasure, and

bloodshed. Once when a bystander asked him why the unjust should not be

put to death, he answered, “Would that it were possible even to restore

the dead to life!”. If anyone was brought before him who had

committed deeds worthy of capital punishment, a reminder of his love of

mankind caused that man’s death penalty to be rescinded.

Two pictures of the emperor in later life are not so flattering.

Theodosius, who inherited his office from his father, Arcadius, was unwarlike.

He lived in cowardice and gained peace by money, not arms. He was

under the control of his eunuchs in everything. They contrived to bring

affairs to such a pitch of absurdity that, though Theodosius was of noble

nature, they beguiled him, to put it briefly, as children are beguiled

with toys, and united in accomplishing nothing worthy of note. Though he

reached the age of fifty years, they prevailed on him to persevere in

certain vulgar arts and in wild beast hunting, so that they, and

Chrysaphius in particular, held control over the empire. Pulcheria took

vengeance on this man

after her brother’s death.

Theodosius received his office from his father, and because he was

unwarlike, lived in

cowardice, and won peace by money not arms, he brought many evils on the

Roman state. Having been brought up under the influence of

the eunuchs, he was well disposed to their every command, so that

even the most important men needed their help. They made many innovations

in political and military affairs, while the men able to manage these

matters were absent from their posts, supplying gold instead, because

of the greed of the eunuchs. And so piracy broke out on the part of Sebastian’s

troops and troubled the Hellespont and Propontus.

Sebastian, the son-in-law of Boniface, who was banished from the West by Aetius

in 434, was master of soldiers (magister utriusque militiae) in the West in 433.

The chief foreign difficulties faced by the Eastern Empire under

Theodosius were with the Huns and will be dealt with later. We must now

turn to affairs in the West and the more immediate dangers faced by that

region.

Honorius was even younger than Arcadius on his father’s death and relied

even more heavily on the powerful help of Stilicho and others. Related to

the royal family both through his wife and his daughters, Stilicho’s

position could not easily be challenged, and for thirteen years he

loyally supported bis master and won high honors for himself in !he

process. At first his chief problem had to do with the Visigoths. This

tribe fleeing before the expanding Hunnish power had crossed into the

empire in 375 and settled there by treaty. In 378 they had revolted and

wiped out a Roman army and killed the Emperor Valens at Hadrianople. After many years Theodosius the Great

had succeeded in settling them in Lower Moesia and had used them in

Italy against the usurper Eugenius in the last year of his life, a

campaign in which they suffered severe losses. At about this time the

tribe, which had never had a single king, united under Alaric. In 395 they

rebelled and spread devastation through Thrace and Macedonia and even

threatened Constantinople until Stilicho faced them in Thessaly. Arcadius,

under Rufinus’ influence, called off any attack on them, the Eastern

troops under Stilicho’s command being handed over to Gainas, and the

Vandal retired to consolidate his power in Italy and the West.

Alaric was thus left a free hand in Greece, through whose ancient cities

he marched as a conqueror and plunderer. Stilicho in 397 sailed to Greece

to attack him, but was again thwarted in his design by Arcadius through

fear of acknowledging that the prefecture of Illyricum was in

the Western domain. For the next year he was engaged in putting down

a Moorish rebellion in Africa, and in 400 he attained the high honor of

the consulship. Alaric in the meantime had settled in Epirus with some

recognition of his position from Arcadius and for four years

apparently remained quiet. In 401, however, he suddenly seized

the chance of invading Italy when the Western armies were distracted

by an incursion of Vandals and other barbarians under Radagaisus across

the upper Danube. Stilicho having dealt with Radagaisus returned to face

the Goths in northern Italy. The fighting was indecisive, but by diplomacy

Alaric was induced to leave the peninsula and to guard the Illyrian

lands for the Western Empire. It was at this time of peril that the court

was moved to the easily defended marsh city of Ravenna.

Though the danger from Alaric and the Visigoths had been temporarily

averted even greater disasters were imminent for the Western Empire. The

provinces of the upper Danube in these years had suffered both from

the barbarians settled within them and from those without, and their

defense in the welter of difficulties faced by the government had been