|

READING HALLTHE DOORS OF WISDOM |

|

|

|

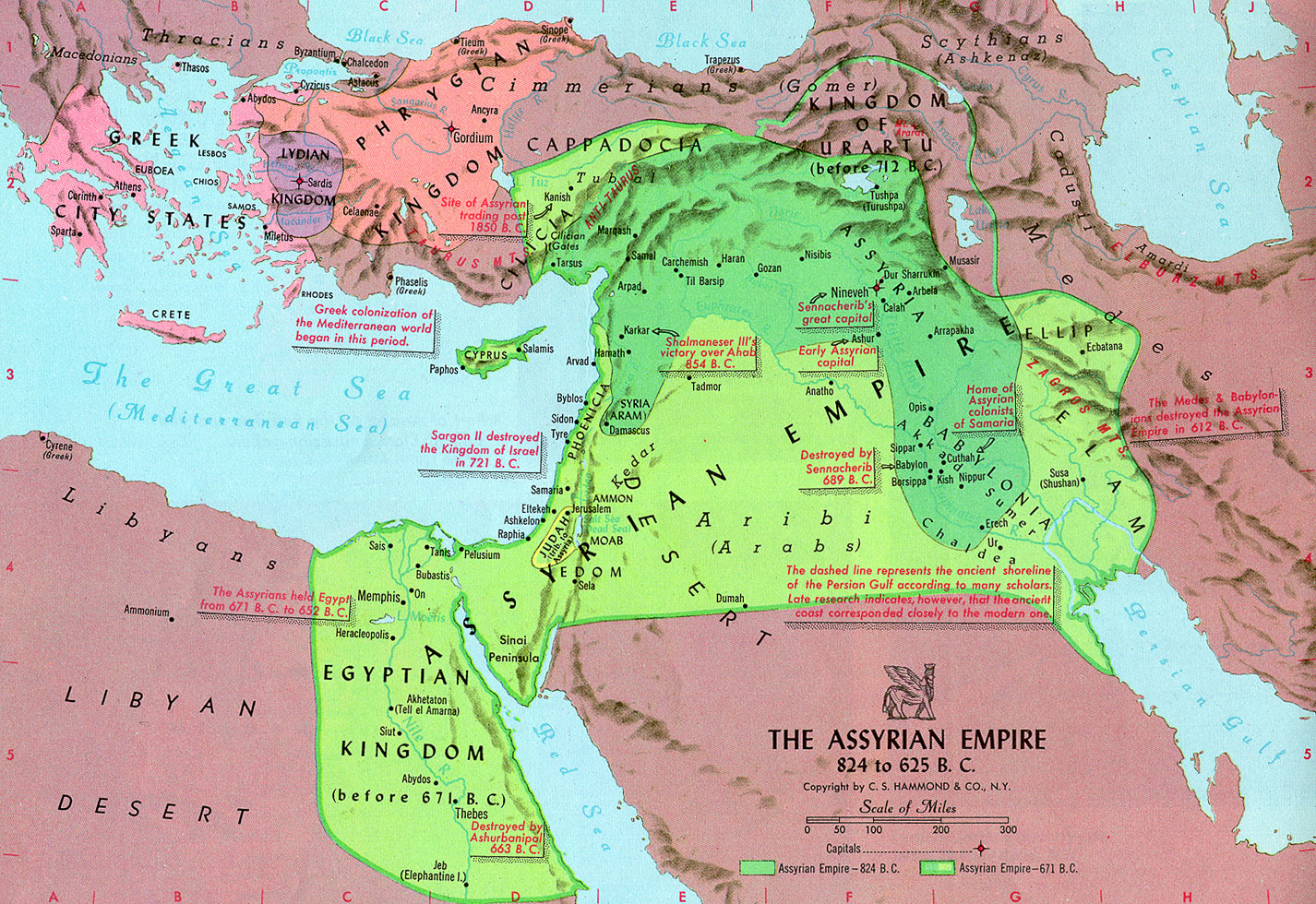

XITHE FALL OF ASSYRIA

ASSHURBANIPAL had maintained internal peace in his empire, and the

prosperity which Nineveh had enjoyed was conducive to a quiet passing of the

succession. He was followed by his son, Asshur Etil Ili Ukinni, who is also known by the shortened form of

his name as Asshur Etil Ili. Of his reign we possess

only two inscriptions. The first occurs in a number of copies, and reads only:

"I am Asshur Etil Ili, king of Kisshati, king of Assyria, son of Ashurbanipal, king of Kisshati, king of Assyria. I caused bricks to be made for

the building of E-Zida in Calah, for the life of my

soul I caused them to be made". The second gives his titles and genealogy

in the same manner, and adds a note concerning the beginning of his reign, but

it is not now legible. Besides these two texts there remain only a few tablets

found at Nippur dated in the second and the fourth years of his reign. These

latter show that as late as the fourth year of his reign he still held the

title of king of Sumer and Accad, and therefore continued to rule over a large

portion of Babylonia, if not over the city of Babylon itself.

The ruined remains of his palace at Calah have been found, and it forms

a strange contrast to the imposing work of Sargon. Its rooms are small and

their ceilings low; the wainscoting, instead of fine alabaster richly carved,

was formed only of slabs of roughly cut limestone, and it bears every mark of

hasty construction.

We have no other remains of his reign, nor do we know how long it

continued. Assyrian records terminate suddenly in the reign of Ashurbanipal, in

which we reach at once the summit and the end of Assyrian carefulness in

recording the events of reigns and the passage of time. It is, of course,

possible that there may be buried somewhere some records yet unfound of this

reign, but it is certain that they must be few and unimportant, else would they

have been found in the thoroughly explored chambers in which so many royal

historical inscriptions have been discovered. It may seem strange at first that

an abundant mass of inscription material for this reign should not have been

produced; that, in other words, a period of extraordinary literary activity

should be suddenly followed by a period in which scarcely anything beyond bare

titles should be written. But this is not a correct statement of the case. The

literary productivity did not cease with Asshur Etil Ili Ukinni. It had already ceased while Ashurbanipal was

still reigning. The story, as above set forth, shows that we have no knowledge

of the later years of his reign. The reign of Asshur Etil Ili Ukinni only continued the dearth of record which

the later years of Ashurbanipal had begun. As in some other periods of Assyrian

history, there was indeed but little to tell. In his later days Ashurbanipal

had remained quietly in Nineveh, interested more in luxury and in his tablets

or books than in the salvation of his empire. In quietness somewhat similar the

reign of his successor probably passed away. He had no enthusiasm and no

ability for any new conquests. He could not really defend that which he already

had. The air must have been filled with rumors of rebellion and with murmurs of

dread concerning the future. The future was out of his power, and he could only

await, and not avert, the fate of Assyria. It did not come in his reign, and

the helpless empire was handed on to his successor.

There is doubt as to who the next king of Assyria may have been. Mention

is found of a certain king whose name was Sin Chum Lishir,

who must have reigned during this period, and perhaps it was he who followed

the son of Ashurbanipal upon the throne. Whether that be true or not, we have

no word of his doings.

The next king of Assyria known to us was Sin Shar Ishkun. He had come to

the throne in sorry times, and that he managed for some years to keep some sort

of hold upon the falling empire is at least surprising. No historical

inscription, in the proper sense of the word, has come down to us from his

reign. One badly broken cylinder, for which there are some fragmentary duplicates,

has been found in which there are the titles and some words of empty boasting

concerning the king's deeds. Besides this we have only three brief business

documents found in Babylonia. These are, however, very interesting because they

are dated two of them in Sippar and the third in Uruk.

The former belong to the second year of the king's reign and the latter to the

seventh year. From this interesting discovery it appears that for seven years

at least Sin Shar Ishkun was acknowledged as king over a portion of Babylonia,

though the city of Babylon was not included in this district.

We have no knowledge of the events of his reign based on a careful

record, as we have had before, and what little we do know is learned chiefly

from the Babylonian inscriptions. The Greeks and Latins contradict each other

so sharply, and are so commonly at variance with facts, amply substantiated in

Babylonian documents, that very little can be made out of them. It is a fair

inference from the records of Nabonidus, whose historiographers have written

carefully of this period, that Sin Shar Ishkun was a man of greater force than

his predecessor. He already possessed a part of Babylonia, and desired to make

his dominion more strong and compact, and also wished to increase it by taking

from the new Chaldean empire, of which there is much to be told later, some of

its fairest portions. Nabopolassar was now king of Babylon, and Sin Shar Ishkun

invaded the territory of Babylonia when Nabopolassar was absent from his

capital city carrying on some kind of campaign in northern Mesopotamia directed

against the Subaru. This cut off the return of Nabopolassar, and brought even

Babylon itself into danger. What was to be done in order to save his capital

but secure allies from some quarter who could assist in driving out the

Assyrians? The campaign of Nabopolassar had won for him the title of king of Kisshati, which he uses in 609, at which time he was in

possession of northern Mesopotamia. It was probably this year or the year

before (610 or 609) that Sin Shar Ishkun attacked the Babylonian provinces.

Nabopolassar found it very difficult to secure an ally who would give aid

without exacting too heavy a price. If Elam had still been a strong country, it

would have formed the natural ally, as it had been traditionally the friend of

the Chaldeans. But Elam was a waste land. The only possible hope was in the

north and west. To the Umman Mandy must he go for

help. At the time of Nabopolassar, and also as late as Nabonidus, the word

Manda was used generally as a term for the nomadic peoples of Kurdistan and the

far northeastern lands. The Babylonians, indeed, knew very little of these

peoples. The Assyrians had come very closely into touch with them at several

times since the days of Esarhaddon. They had felt the danger which was

threatened by the growth of a new power on their borders, and they had suffered

the loss of a number of fine provinces through it. This new power was

Indo-European, and the people who founded and led it are confused by the Greek

historians of a later day with the Medes. To appeal to the Manda for help in

driving out the Assyrians from Babylonia was nothing short of madness. There

were many points of approach between Babylonia and Assyria, there were many

between Assyria and Chaldea. There was no good reason why these two peoples

should not unite in friendship and prepare to oppose the further extension of

the power of the Manda. The Assyrians certainly knew that the Manda coveted

Assyria and the great Mesopotamian valley, and the Babylonians might easily

have learned this if they did not already know it.

But Nabopolassar either did not know of the plans and hopes of the

Manda, or, knowing them, hoped to divert them from himself against Assyria, and

he ventured to invite their assistance. They came not for the profit of

Nabopolassar, the Chaldeans, and Babylonia, but for their own aggrandizement.

Sin Shar Ishkun and his Assyrian army were driven back from northern Babylonia

into Assyria, and Nabopolassar at once possessed himself of the new provinces.

The Manda pushed on after the Assyrians, retreating toward Nineveh. Between

them there could only be the deepest hostility. In the forces of the Manda or

Scythians there must be inhabitants of provinces which had been ruthlessly

ravaged by Assyrian conquerors. They had certainly old grievances to revenge,

and were likely to spare not. There is evidence in abundance that Assyria was

hated all over western Asia, and probably also in Egypt. For ages she had

plundered all peoples within the range of her possible influence. Everywhere

that her name was known it was execrated. The voice of the Phoenician cities is

not heard as it is lifted in wrath and hatred against the great city of

Nineveh, but a Hebrew prophet, Nahum, utters the undoubted feeling of the whole

Western world when, in speaking of the ruin of Assyria, he says: "All that

hear the bruit of thee the report of thy fall clap

the hands over thee: for upon whom bath not thy wickedness passed

continually?"

Nabopolassar did not join with the Manda in the pursuit of the

Assyrians, for he was anxious to settle and fix his own throne and attend to

the reorganization of the provinces which were now added to the empire. If the

Manda had needed help, they might easily have obtained it, for many a small or

great people would gladly have joined in the undoing of Nineveh for hatred's

sake or for the sake of the vast plunder which must have been stored in the

city. For centuries the whole civilized world had paid unwilling tribute to the

great city, and the treasure thus poured into it had not all been spent in the

maintenance of the standing army. Plunder beyond dreams of avarice was there

heaped up awaiting the despoiler. The Manda would be willing to dare

single-handed an attack on a city which thus promised to enrich the successful.

The Babylonians, or rather the Chaldeans, had given up the race, content to

secure what might fall to them when Assyria was broken by the onslaught of the

Manda. It will later appear in this narrative that Egypt was anxious to share

in the division of the spoil of Assyria, and actually dispatched an expedition

northward. This step was, however, taken too late, and the Egyptians were not

on the ground until the last great scene was over. The unwillingness of

Nabopolassar and the hesitancy or delay of other states left the Manda alone to

take vengeance upon Assyria. Whether the fleeing Assyrians made a stand at any

point before falling back upon the capital or not we do not know. If they did,

they were defeated and at last were compelled to take refuge in the capital

city. The Manda began a siege. (The memory which the Greeks and Latins handed

down from that day represented the Assyrians as so weak that they would fall an

easy prey to any people. This was certainly erroneous. There is a basis of

truth for the story of weakness, for there were evident signs of decay during

the reign of Ashurbanipal. These had, however, not gone so far as to make the

power of Assyria contemptible. Weakened though the empire had been by the loss of

the northern provinces through the great migrations, and weakened though it had

been by the loss of Egypt, and weakened though it had been by the terrible

civil war between Ashurbanipal and Shamash Shumukin, it was still the greatest

single power in the world. It had, indeed, lost the power of aggression which

had swept over mountain and valley, but in defense it would still be a

dangerous antagonist).

When the Scythian forces came up to the walls of Nineveh they found

before them a city better prepared for defense than any had probably ever been

in the world before. The vast walls might seem to defy any engines that the

semi-barbaric hordes of the new power could bring to bear. Within was the

remnant of an army which had won a thousand fields. If the army was well

managed and the city had had some warning of the approaching siege, it would be

safe to predict that the contest must be long and bloody. The people of Nineveh

must feel that not only the supremacy of western Asia, but their very existence

as an independent people, was at stake. The Assyrians would certainly fight

with the intensity of despair. We do not know, unfortunately, the story of that

memorable siege. A people civilized for centuries was walled in by the forces of a new people fresh, strong, invincible. Then, as often in

later days, civilization went down before barbarism. Nineveh fell into the

hands of the Scythians. Later times preserved a memory that Sin Shar Ishkun

perished in the flames of his palace, to which he had committed himself when he

foresaw the end.

The city was plundered of everything of value which it contained, and

then given to the torch. The houses of the poor, built probably of unburnt bricks, would soon be a ruin. The great palaces,

when the cedar beams which supported the upper stories had been burnt off, fell

in heaps. Their great, thick walls, built of unburnt bricks with the outer covering of beautiful burnt bricks, cracked open, and

when the rains descended the unburnt bricks soon

dissolved away into the clay of which they had been made. The inhabitants had

fled to the four winds of heaven and returned no more to inhabit the ruins. A

Hebrew prophet, Zephaniah, a contemporary of the great event, has described

this desolation as none other: "And he will stretch out his hand against

the north, and destroy Assyria; and will make Nineveh a desolation, and dry

like the wilderness. And herds shall lie down in the midst of her, all the

beasts of the nations: both the pelican and the porcupine shall lodge in the chapiters thereof: their voice shall sing in the windows;

desolation shall be in the thresholds: for he hath

laid bare the cedar work. This is the joyous city that dwelt carelessly, that

said in her heart, I am, and there is none else beside me: how is she become a

desolation, a place for beasts to lie down in everyone that passeth by her shall hiss, and wag his hand". Nineveh

fell in the year 607 or 606, and the waters out of heaven, or from the

overflowing river made the soft clay into a covering over the great palaces and

their records. The winds bore seeds into the mass, and a carpet of grass

covered the mounds, and stunted trees grew out of them. Year by year the mound

bore less and less resemblance to the site of a city, until no trace remained

above ground of the magnificence that once had been.

In 401 BC a cultivated Greek leading homeward the fragment of his

gallant army of ten thousand men passed by the mounds and never knew that

beneath them lay the palaces of the great Assyrian kings. In later ages the Parthians

built a fortress on the spot, which they called Ninus,

and other communities settled either above the ruins or near to them. Men must

have homes, and the ground bore no trace of the great city upon which dire and

irreparable vengeance had fallen. But, though cities might be built upon the

soil and men congregate where the Assyrian cities had been, there was in

reality no healing of the wound which the Manda had given. The Assyrian empire

had come to a final end. As they had done unto others so had it been done unto

them. For more than a thousand years of time the Assyrian empire had endured.

During nearly all of this vast period it had been building and increasing. The

best of the resources of the world had been poured into it. The leadership of

the Semitic race had belonged to it, and this was now yielded up to the

Chaldeans, who had become the heirs of the Babylonians, from whom the Assyrians

had taken it. It remained only to parcel out, along with the rest of the

plunder, the Assyrian territory. The Manda secured at this one stroke the old

territory of Assyria, together with all the northern provinces as far west as

the river Halys, in Asia Minor. To the Chaldeans, who were now masters in

Babylonia, there came the Mesopotamian possessions and, as we shall later see,

the Syro-Phoenician likewise. By this change of ownership the Semites retained

the larger part of the territory over which they had long been masters, but the

Indo-Europeans had made great gains. (A life-and-death struggle would soon begin

between them for the possession of western Asia)

|

||

|

|