|

JAPAN'S HISTORY LIBRARY |

|

|

|

THE RESTORATION OF THE MIKADO

AND

THE GREAT EMANCIPATION1867-1912

THE green shoot of New Japan was coming through the

ground. One of the chief hindrances to its growth was to disappear in 1867, with

the death, early in the year, of the Emperor Ko-mei,

who had reigned twenty years. Ko-mei Ten-no is

supposed to have been bitterly anti-foreign, but it should be borne in mind

that, in his time, the Emperor's personal opinion was but the reflection of the

views of the women by whom alone he was constantly attended, and of the

Imperial princes and the very few nobles sufficiently exalted in rank to

approach his sacred person. Towards the close of his reign, his entourage,

taught by the stern logic of facts, had become more resigned to the unwelcome

presence of foreigners in the "Holy Land" of Japan; but it was hardly

to be expected that, as long as their august sovereign occupied the Imperial

Palace at Kioto, they would openly recant their

opinions. They toned down their anti-foreign diatribes considerably some time

before the Emperor's death on February 13, 1867; the advent of his successor,

his son Mutsu-hito—born on November 3, 1852, and

enthroned, with ceremonies equivalent to an Occidental coronation, on October

13, 1868—gave them full opportunity for an avowed change of policy. The boy of

fifteen, who now became the one hundred and twenty-third sovereign of Japan

"of one unbroken line", by far the oldest dynasty in the world, was

unhampered by any anti-foreign edicts. He could accept the advice of his councillors, speaking of great things that were impending,

of an entire change of front towards the "haughty barbarians", of a

complete alteration in the system of government, of innovations and reforms that

would have staggered the late monarch, to whom they would have seemed impious

and accursed.

Fortunately for Japan, this new Emperor was no

weakling, but strong in health—he grew up a fine, deep-chested man, tall for a

Japanese, five feet eight inches in height—and strong in character. Deeply

imbued with the awful responsibility of his position, animated by a strict

sense of duty, his Imperial Majesty gave throughout his long and epoch-making

reign, many proofs of shrewd common-sense and of that supreme political

sagacity which consists in the selection of the best advisers and in a wise

abstention from interference, except in cases of great emergency. In such times

of crisis, the Emperor Mutsu-hito always spoke the

right word at the proper moment, and all Japan bowed in awe struck obedience.

How much of this policy was his own, how much was due to the Elder Statesmen he

consulted, will probably never be known; this much is certain, that the

acceptance of good advice, and the use thereof at the right moment, constitute

by themselves political wisdom of the soundest kind, and with such wisdom the

stately, imperturbable, benign Emperor Mutsu-hito was

amply endowed. The Japanese National Anthem, "Kimiga yo, etc.," expresses a pious wish for the long

continuance of the monarch's reign; and even this was granted to new Japan, as

the great Emperor had completed a reign of forty-five years at his lamented

death, on July 20th, 1912.

Surely no reign in history can show such a record of

progress, of reform, of peaceful achievement, of military glory by land and

sea, as that of Mutsu-hito—a name meaning literally,

"Benign Man"—one hundred and twenty-third sovereign of Old, first

Emperor of New, Japan! With his accession a new wind began to blow in official

circles; the Court of Kioto was no longer a hotbed of

anti-foreign fanaticism. The Shogun's government, which had been only outwardly

friendly to foreigners, now earnestly strove to cultivate amicable relations,

especially with Britain, with the United States, and with France. Napoleon III

lost no opportunity of showing how well he was disposed towards the Baku-fu.

Misinformed as to the state of Japan—as in so many other matters—that schemer

and dreamer "backed the wrong horse", at least with moral support,

and might have given material aid, in the hope of reaping the Shogun's

gratitude, had not the march of events been too rapid for Napoleon's vague

plans to mature.

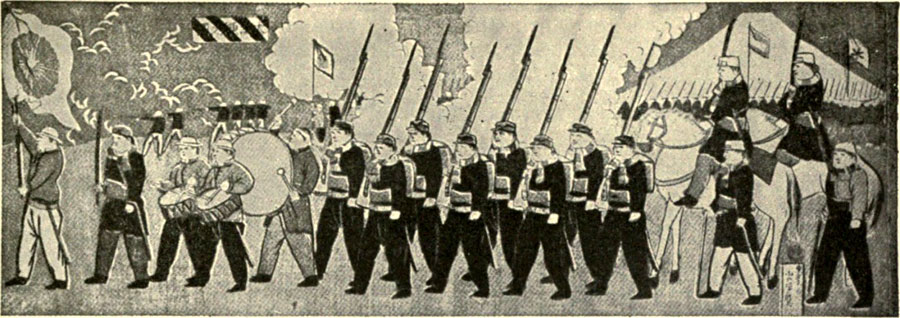

French influence was paramount at this time in the

Baku-fu's military councils; at the Shogun's request

the French Government selected a military mission, which set to work to train

the Baku-fu's motley troops and to educate young

Samurai in the art of war. The mission, consisting of five officers, under

Captain Chanoine, of the Staff Corps, arrived in

January, 1867. Its activity was, a year later, transferred by the course of

events to a wider sphere, when the nucleus of a truly national army was formed.

The French instructors remained at their posts until after the Franco-German

war had opened the eyes of the Japanese to the fact that another great military

Power had arisen, under whose scientifically calculated, overwhelming blows,

the gallant but ill-organised and badly-directed Army

of the Second Empire had crumbled into dust.

New organisers and

instructors were procured from the victorious German General Staff, the late

General Meckel at their head, and for years the German officers brought their

consummate knowledge of military science and their native thoroughness to bear

on shaping and moulding into its present marvellous approach to perfection the excellent material

prepared by their French predecessors.

The year of the arrival of the French military mission

saw the advent, in September, 1867, of a British naval mission, under Commander

Tracey, R.N., invited by the Shogun to organise and

train his Navy, which, consisting in 1865 of five vessels of European build—one

paddle-steamship, two square-rigged sailing ships for training purposes, a

steam-yacht presented to the Shogun by Britain, and a three-masted steamer—had

grown to the total strength of eight ships. The downfall of the Shogunate

interrupted the labours of this first naval mission

only five months after its arrival. Its work was taken up in 1873 by the second

British naval mission, under Commander Douglas, R.N., now Admiral Sir Archibald

Douglas, which remained in active operation six years. After its departure, a

few British naval officers, warrant officers, and petty officers, were still

employed as instructors in special branches, with Commander Ingles, R.N. (now

Rear-Admiral, retired), as naval adviser to the Japanese Admiralty: but their

number became steadily less as the Japanese began to feel confidence in their

own naval efficiency. The last Occidental officer to be employed by the

Japanese Government was Engineer-Commander A. R. Pattison, R.N., who returned

to his duty in the Royal Navy in 1901. The work of these men, sailors and

soldiers, British, French, German, and Italian—for a couple of Italian

artillery officers organised the great military

arsenal and gun-foundry at Osaka—whether performed in the office, in the

lecture-room, on the parade-ground, or at sea, was herculean, and the success

proportionate. It is to them, in great measure, that Japan owes the efficiency

that has made, as the native phrase has it, her glory to shine beyond the

seas". In 1867, that glory was not yet apparent, the outlook was cloudy,

and many shook their heads anxiously, anticipating a bitter and long-continued civil

war between the Imperialists and the Shogun's party. Their forebodings were not

justified by events; some fighting took place—the disruption and reconstruction

of the whole system of government, the uprooting of hoary institutions, and the

consequent unavoidable disturbance of every class interest, could not happen

without some violence being used—but the armed struggle was short and confined

to a few districts.

It was at no time a great regional conflict, like the

American Civil War, nor did it split the whole nation into two belligerent

parties, opposing each other in every part of the land, as in the English Civil

War between King and Parliament. The conflicting parties were too unevenly

matched for the struggle to become a severe one, and the leader of the losing

side, the Shogun Kei-ki, was not made of the stem stuff that prolongs the game

to the utmost, even with all the chances adverse. Meeting with bitter opposition

from the great clans of the west and south, and beset by financial anxieties,

an opportunity of ridding himself of his uneasy office and of its crushing

responsibilities presented itself when, in October, 1867, Yama-no-uchi Yo-do, the retired Lord of Tosa, addressed a letter to him wherein he earnestly

advised him to resign the governing power and to hand it over to the sovereign,

thus restoring that unity of rule for lack of which the empire was distracted

and weak, a prey to foreigners and "a butt for their insults". Kei-ki

took the great noble's advice to heart, and, by a manifesto dated November 9th,

1867, resigned his office and returned to the Emperor the delegated powers he

held as Shogun. The Emperor accepted, and summoned the feudal lords to Kioto to discuss matters and to consult as to the new order

of things. The old order was gone, never to return.

The Shogunate, after an existence of nearly seven

centuries as a ruling power, had succumbed to senile decay. In Tokugawa hands

it had given Japan two centuries and a half of unbroken peace. Its very success

in maintaining order in the land—an object it attained by the exercise of

cunning diplomacy rather than by a display of force—made hosts of enemies who

eventually compassed its downfall. Its worst legacy is the widely ramified

system of spying it brought to the pitch of perfection, a system that has stood

Japan in good stead in the preparations for her wars, but has severely damaged

her national character. The Japanese are the best spies in the world; the

Baku-fu system trained their ancestors to be eaves-droppers, but they have

small cause to be thankful for it. They would have been victorious against

China, even against Russia, had the Intelligence Departments of their Navy and

their Army been less wonderfully efficient; but more than two generations must

pass before they get the spy-taint out of their blood.

At present it poisons life in Japan in almost every

phase; until its disappearance no real fellow-feeling is possible between Japanese

and Occidentals. Spies had a busy time in 1868 and the next few years, for with

the restoration of the ruling power into the hands of the Emperor the Samurai

class were plunged into a whirlpool of intrigues, of plots and counter-plots,

of schemes of reform (some admirably practical, others visionary), of

accusations and suspicions, a feeling of bewilderment permeating all at the

seemingly inexplicable conduct of the leaders of the Imperialist party. During

the struggle against the Shogunate, "Out with the Foreigners!" had

been the War-cry; now the Shogunate was no more, behold the victors sitting at

meat with the hated "barbarians", worse still, inviting them to Kioto, to the sacred precincts of the Court and—it was

hardly to be believed—allowing them to gaze on the divinely-descended Emperor's

face in solemn audience! Such impious proceedings must be stopped, and the

disgusted Samurai kept his long sword keen as a razor and used it, as

opportunity offered, on the "ugly barbarian", the "hairy

Chinaman", as the Occidental was scornfully called, and on the native

traitor, for so seemed to the swordsman the Japanese who had become defiled by

associating with foreigners.

This anomalous state of things continued until well

into the seventies, the Court and the Government markedly friendly to

Occidentals, the officials adopting the same attitude, sometimes painfully

against their inclination, but the great body of the Samurai, on the other

hand, inspired by fanatical anti-foreign feelings, leading to the commission of

such outrages as the indiscriminate firing on the foreign settlement at Kobé by troops of the Bizen clan,

on February 4th, 1868; the murder, by Tosa clansmen,

of eleven French man-of-war's men at Sakai on March 8th of the same year (a

crime for which an equal number of the assassins had to commit hara-kiri); and,

most audacious of all, the fierce attack on the procession in the midst of

which the British Minister, Sir Harry Parkes, was riding to the palace at Kioto, on March 23rd, 1868, to be received for the first

time by the Emperor.

The assailants were only two, members of a

newly-raised force of red-hot Imperialists, the Shim-pei, or

"New Troops", a corps intended to act as an Imperial body-guard,

formed principally of yeomen, landed gentry holding small estates and

independent of any feudal lord, with a considerable admixture of Ronin and

other adventurers, ex-Buddhist priests and the like. The two fanatics managed

between them to wound, with their long swords, nine out of the eleven ex-constables

of the Metropolitan Police who, tired of the monotony of their London beats and

"point-duty", had volunteered to serve as the mounted escort attached

to the British Legation in Japan. They also wounded one of the military escort

of 48 men (furnished by the detachment of the 9th Foot, then guarding the

foreign settlement at Yokohama), a Japanese groom in the British Minister's

employ, and five horses.

They ran "amok" down the line of the

procession till one was stopped by a British bullet and a British bayonet (he

was ultimately degraded from his rank as a Samurai and decapitated), and the

other cut down by a Japanese official, Goto Shojiro, of the Foreign Departments, and beheaded by a

Japanese officer, Nakai Kozo, who was cut on the head

in a brief but fierce sword-fight with the miscreant. The British Government recognised the gallantry of Goto and Nakai by the presentation to each of them of a

handsome sword of honour. An Imperial Edict, dated

March 28th, 1868, threatened the perpetrators of outrages on foreigners with a

punishment the two-sworded gentry feared more than

anything else: the striking of their names off the rolls of the Samurai. The

edict clearly stated the Emperor's resolve to "live in amity" with

the Treaty Powers—two great strides forward in the history of New Japan: the

first earnest attempt to check outrages and the first proclamation of the new

Emperor's abandonment of the old anti-foreign policy. From this time outrages

on foreigners became fewer, until they practically ceased to occur, with the

exception of the isolated acts of criminal lunatics; there is little doubt it

was while in an insane condition that the policeman Tsuda Sanzo slashed at and wounded the Tsarevitch, now the Tsar Nicholas II, at Otsu, in

1891, and Koyama, who shot Li Hung Chang in the face, during the peace

negotiations at Shimonoseki, in March, 1895, was halfwitted.

In the opening years of the twentieth century, the lives and property of

foreigners are as safe as in any civilised country—safer, indeed, than in most of them, the statistics of Japan showing

that crime is not very prevalent, and the police being perhaps the most

efficient in the world.

If this general state of security be, as it

undoubtedly is, greatly to the credit of the way in which Japan is governed and

of the law-abiding character of her people, it must be admitted that in one

respect life is, unfortunately, still less safe than in most Occidental

countries.

Japanese statesmen still run greater risks than most

others, and have to be carefully guarded, for political assassination, which

has cut off in their prime some of the noblest patriots and most enlightened

administrators among the makers of New Japan, is still an ever-present danger.

It is, of course, punished with the extreme penalty of the law; but its

disappearance cannot be expected until the popular feeling towards it changes

completely. Purity of motive, and zeal, however misguided, for what the

assassin considers to be the public good, still justify his murderous deed in

the eyes of the Japanese people. On April 6th, 1868, the Emperor assembled

the Court nobles and great feudal lords at the Palace of Ni-jo, in Kioto, and, in their presence, took a solemn oath, by which

he promised that a Deliberative Assembly should be constituted, so that all

measures for the public would be, in future, decided by public opinion; that

old abuses should be removed, and that impartiality and justice should reign in

the government of the nation "as they were to be seen in the workings of

Nature". The Emperor promised, further, that intellect and knowledge

should be sought for throughout the world, in order to assist in establishing

the foundations of the empire.

Thus was the seed of constitutional government sown in

Japan, establishing once for all the principle of government by the will of the

majority. The plant has grown apace; it is now a healthy tree, doing quite as

well, all things considered, as similar ones planted in countries in which they

were as exotic as in Japan. Some of the fruit borne by its branches has been

sour enough; but it should be remembered that even the Mother of Parliaments

has not always given her numerous offspring throughout the world an example of

supreme dignity. That there is a certain amount of corruption in Japanese

parliamentary politics is undeniable; but its proportions are far smaller than

they were a few years ago. Scenes in the House still occur occasionally, but

they have, fortunately, hardly ever sunk to the level of absolute savagery that

has so often disgraced the sittings of the Reichsrath in Vienna and of the Lower House of the Hungarian Diet at Budapest. In one

respect, the Parliament of Japan has been a brilliant model for the legislative

assemblies of the world: at the outset of both the great wars in which New

Japan has engaged, the Leader of the Opposition, speaking on behalf of his

adherents, solemnly announced that thenceforward, until Japan's victorious

sword returned to its sheath, there would be no more parties in the council of

the nation; in the presence of a national crisis all Japan would be as one man.

In 1868, however, Japan's constitutionai government was in its earliest embryonic stage; divided counsels, intrigues,

plots and counterplots still confused the nation and obscured the great issues

at stake. The ex-Shogun Kei-ki had retired to the monastery of Kwanyei-ji, at Uyeno, in Yedo, and showed signs of disinclination to play any

further part in politics. The Imperial troops were advancing on Yedo, the forts in the bay there being handed over to them

without a blow on April 4th, 1868. On the 25th of the same month the Imperial

ultimatum was presented to Kei-ki, summoning him to hand over the castle of Yedo, his warships and armaments, and to retire into

seclusion in the from province of Mito.

Kei-ki accepted these terms and retired to Mito. The

other conditions of the ultimatum were speedily complied with, except that

relating to the transfer of the Shogunate's fleet, which was to have taken

place on May 3rd, the day of Kei-ki's departure from Yedo,

but was postponed owing to a violent storm. The next morning it was found that

the squadron had put to sea. It subsequently returned and several months were

spent in negotiations as to its surrender, the Imperial Government being

obliged to temporise, as it had no naval force

wherewith to compel submission. In the night of October 4th, 1868, the fleet,

consisting of eight steam vessels, under the command of Captain Enomoto Kamajiro, whose naval

education had been received in Holland, from 1862 to 1867, sailed from Yedo Bay for Yezo, where, at

Hakodate, its commander and the three or four thousand adherents of the

Tokugawa who sailed with him, attempted to set up a republic.

It seems more than likely that the idea of such a very

un-Japanese experiment did not germinate spontaneously in the hardy sailor's

mind, but was, in some way, connected with the presence on his staff of Captain

Brunet and another member of the French military mission, as well as of two

midshipmen from a French Warship, all of these having joined the expedition

secretly, apparently without the knowledge of the French Minister. The strange

kind of "Republic," which was anything but democratic, for only

Samurai had votes, was shortlived. As soon as the

Imperial Government could improvise a squadron of its own, it began operations

against Enomoto, troops also attacking him by land.

Short but sharp fighting took place by sea and land, in May and June,

1869,resulting in the total discomfiture of the "rebels," as they had

been declared by a decree of October 10th of the previous year. Their leaders

surrendered, their forces were disarmed, and the adventurous Frenchmen went on

board a warship of their own country and placed themselves in the hands of her

captain. They were conveyed as prisoners to Saigon, together with one of the

runaway French midshipmen who had been captured by the Japanese Imperial

forces at the stranding of the rebel ship in which he was serving, and who had

been given up to the French Legation.

Thus ended, in a miserable manner, the hare-brained

adventure of Enomoto and his followers. A remarkable

sign of the times, auguring well for the wisdom with which the new Government

was imbued, may be found in the clemency extended to the rebel leaders. In Old

Japan their lives would certainly have been forfeited to the victors. After

serving a term of imprisonment, they were, under the new regime, pardoned by

the Emperor. Many of them lived to serve him faithfully in high official posts. Enomoto himself became a Viscount, a Vice-Admiral,

and a highly-respected statesman, who rendered good service in several

Cabinets, holding in turn all the portfolios except those of War, Finance, and

Justice.

Meanwhile, other adherents of the Tokugawa besides the

navy of the late Shogunate offered armed resistance to the new order of things.

The powerful Aidzu clan had retired into their

mountain fastnesses, after presenting to the Government a petition indicating

their intense dissatisfaction with the state of affairs. They were joined by large

numbers of malcontents, and prepared for war. About twenty-five clans

ultimately joined this northern coalition of rebels, their headquarters being

established in the castle of Waka-matsu, which was

besieged by the Imperial forces during the month of October, 1868.

After severe fighting, the besieged making a heroic defence, the castle capitulated, on November 6th, the

Imperial Army owing their victory chiefly to the superiority of their armament,

which was of the most modern kind. In Yedo, the

Tokugawa retainers, naturally dissatisfied at the disestablishment of their

clan from the position of power it had enjoyed for 265 years, had formed

themselves into armed bands, under the name of Shogitai,

meaning "the corps that makes duty clear." They seized the person of

the Imperial Prince, who, under the title of Rinnoji-no

Miya, was abbot of the great Buddhist temple at Uyeno,

a post always held by a son of a Mikado—an artful piece of policy on the part

of the Shogunate, which thus always had a candidate ready to its hand in the

event of a break in the direct succession to the Imperial throne.

The Shogitai proposed to set

up their more or less willing captive as a rival emperor, and proceeded to

establish themselves in the groves round the temple, then known as Toyeizan, and now forming part of the beautiful Uyeno Park. They attracted a host of dissatisfied

adventurers and unemployed Samurai, who swaggered about on high clogs, with

long swords stuck in their girdles, scowling at the Kingire,

as the Imperial troops were called from the " scraps of brocade" sewn

to their clothes as a distinguishing mark. Conflicts between the two parties

were frequent, especially when the Tokugawa adherents could fall upon an

isolated Imperialist in some remote street.

The proceedings of these lawless bands of

swashbucklers became at last so outrageous that a decree was issued proclaiming

them outlaws, and, as they refused to disperse, the forces of the loyal clans,

those of Satsuma at their head, attacked them on July 4th, 1868, and utterly

defeated them, chiefly owing to the execution done by two Armstrong field-guns

served by the men of Hizen. In the course of the

fight, the Hondo, or great hall of the monastery, was destroyed by fire. The

Imperialists were now in full possession of Yedo, the

municipal government of which they now took into their own hands.

The spirit of the Tokugawa clan had been broken, and

their importance was further diminished by a great reduction in the extent of

their territorial possessions, fixed by an Imperial decree. In the same year

(1868), the birthday of the Emperor Mutsu-hito,

November 3rd, was constituted a national holiday, and the important step was

taken of decreeing that thenceforward there should be only one nengo, or chronological epoch, for each reign, not, as

hitherto, liable to be altered, at the Emperor's will, on the occurrence of any

notable event. The epoch beginning with the late Emperor's reign was ordered to

be known as ''Enlightened Rule" (Meiji), surely a well-justified choice of

name. Thus the year of grace 1914 is the forty-seventh year of Meiji, or the

year 2574, of the existence of the Japanese Empire as reckoned from the

beginning of the reign of its alleged founder, Jimmu,

in 660 B.C., a mode of computing time introduced in 1872. A momentous decision

was now taken by the makers of New Japan. It was resolved that the Emperor

should reside, at least for a time, at Yedo, the city

founded by the "usurpers," as the Shogun were now commonly called by

the triumphant Imperialists; and his Majesty, travelling by land, in a closed

palanquin, arrived in the Tokugawa capital on November 26th, 1868. He found it

no longer Yedo, but Tokio,

the ''Eastern Capital", his Government having changed the city's name as a

sign, easily understood by all and sundry, that the old order of things that centred in Yedo had passed away

never to return, while a new era was dawning for the empire of which Tokio was to be the capital.

This action of the Government, and its effect on the

popular mind, may best be understood if we imagine the first Republican

Government of France changing the name of Paris, to celebrate the great

revolution of 1789-1793, as the present Municipal Council of the French capital

delights in changing the names of streets to commemorate various celebrities it

holds in high honour; or if we can conceive, in our

wildest dreams, the British Cabinet of 1832 changing the name of London to mark

the passing of the great Reform Bill. The making of Tokio into the sole seat of the Imperial Government took place only after a

transitory stage, when there were virtually two capitals—Tokio,

the Eastern one; and Kioto, which was renamed Saikio, or "Western Capital."

With the extinguishing of the pinchbeck

"republic" in Yezo, in October, 1869, all

armed resistance to the new order of things seemed to have ceased. The

ex-Shogun Kei-ki was living quietly in retirement —a state in which he long

continued to remain—obtaining, in latet years,

permission to reside in Tokio, where he was simply an

amiable old nobleman of no political importance. The new Government continued

to show its wisdom by the clemency with which the leaders of the rebellions

were treated. The Imperial Prince-Abbot, Rinnoji-no

Miya, was pardoned, and, under the title of Kita-Shira-kawa-no Miya, proceeded

to Germany, where he resided for many years, ultimately returning to hold high

command in the Imperial Army, in whose service he died from illness contracted

during the occupation of Formosa at the close of the war with China, 1895. In

January, 1869, the Emperor for the first time went on board one of his

warships. He returned shortly afterwards, by land, to Kioto,

where he was married, on February 9th, to the Princess Haruko, "Child of

Spring," of the house of Ichijo, his senior by

about two years.

This noble-hearted lady, as sweet and graceful as her

own poetical name, exerted an incalculably great influence for good in the land

over which her spouse reigned. Keeping carefully aloof from politics, she was

the guiding spirit in Emperor every good work, bestowing her high patronage

especially on institutions connected with female education, with the care of

the sick and wounded, of orphans, and of all who are in distress. Her Imperial

Majesty contributed generously from her privy purse to these charities and

other good works, taking a personal, active part in their management. Japan has

indeed been fortunate in having so long at the head of the nation a sovereign

worthy of the veneration, amounting almost to worship, with which he was

regarded, and, in his gracious consort, an Empress who may be described as the

very embodiment of the noble spirit, the devotion, the quiet dignity, the

gentleness and sweetness that are the characteristics of Japanese womanhood.

In March, 1869, the Official Gazette (Kampo) published a memorial to the throne by the feudal

lords of the four leading clans—Satsuma, Cho-shu, Tosa, and Hizen—offering up lists

of their entire possessions and of their retainers, and placing the whole at

the disposal of his Imperial Majesty. In this remarkable document, the drafting

of which has been attributed to a Samurai, Kido Junichiro, one of the foremost

makers of New Japan, the princely memorialists state: "The place where we

live is the Emperor's land, and the food we eat is grown by the Emperor's

men," and they proceed, in burning words of devoted loyalty, to beg the

Emperor to take possession of all they own, and to assume the direct rule over

the empire. Their example was followed by all but 17 of the 276 Daimiyo. The offer was accepted, and the greatest

revolution of modern times was thus completed with less strain and friction

than had accompanied any great change in the world's history. It cannot be said

that the restoration of the Imperial power was a bloodless revolution. As

already related, the malcontents had made a short but stout resistance in arms,

and blood was still to flow before the new state of things could be firmly

established. Nevertheless, the loss of life and destruction of property were

astonishingly small when it is considered what immense issues were at stake.

Had the French nobility possessed the wisdom of the counsellors who advised the Daimiyo, and the good sense shown by the latter in

adopting their advice, the great Revolution at the end of the eighteenth

century would have been a peaceful one, and France would have been spared

"the red fool-fury of the Seine."

The feudal lords were not immediately dispossessed of

all their power, although their revenues were greatly diminished and their

warships and armed retainers were taken over to form the nucleus of the

Imperial Navy and Army respectively. With that prudence that has always been

characteristic of the policy of the rulers of New Japan, they caused the Daimiyo to be appointed governors (Chihanji)

to administer their old clans (Han) on behalf of the Emperor. This period of

transition lasted till 1871, when the Han were converted into Ken, or

prefectures, governed by prefects appointed by the Imperial Government, and the

old feudal lords became simply members of the aristocracy, as they are today

with no administrative functions and no political power beyond their votes in

the House of Peers. If of a rank lower than that of a marquis, they must be

elected by their peers, for a term of seven years, to the delegation

representing their particular rank in the House.

Before feudalism could be looked upon as completely

abolished, the division of the people into strictly separated classes, or

castes, had to be effaced; the various elements that had for centuries been

kept apart, with the very object of preventing combination between them, had

now to be welded into a nation of men equal before the law, possessing equal

rights and duties, and permeated by a feeling of brotherhood within the borders

of the empire—in short, a nation had to be established on the only principles

that can ensure national strength. Two short years saw the greater part of this

stupendous work accomplished.

By the end of 1871 feudalism had been entirely

abolished, leaving behind it only a very natural sentimental attachment on the

part of those who had been retainers towards the great families to which they

had owed allegiance as their forefathers had done for so many centuries. By the

noblest stroke that ever moved an imperial pen two classes of human beings who

had hitherto enjoyed no legal rights, the Eta, a despised class who had for

centuries been occupied in trades considered degrading, such as the slaughtering

of animals, the preparation of leather, digging of criminals graves, and the Hinin, or "Non-humans", a still lower class of

outcasts, were admitted to citizenship. This grand act of emancipation raised

nearly a million of human beings (287,111 Eta, and 695,689 Hinin)

from a position little different from that of cattle to a state of manhood. The

nation was now divided into three great social orders: the Kwazoku,

or nobility; the Shikozu, or gentry, the old Samurai

class; and the Heimin, embracing all the rest of the

people. This division exists today, but it must be noted that there is, in

practice, absolutely no dividing wall between one and the other of these

classes. A capable member of the Heimin may rise, by

his own exertions, to the highest post in the State, and intermarriage between

one class and another, although still infrequent, is perfectly feasible.

Socially, there is far less demarcation between the classes than in the

monarchical countries of Europe, or than between the millionaires of the United

States of North America and their less wealthy fellow-citizens.

Along with so much that is good, Japan has imported from the Occident more than one thing that would better have been left outside its borders; there is, however, one foul thing that degrades Occidental, and especially British, humanity that has not obtained any hold in Japan : the Japanese has not become a snob. It is, indeed, one of the greatest marvels in a land of wonders that the intense feeling of veneration for the sovereign, the respect for his Court, the sentimental attachment to the ex-feudal lord, and the awe inspired by official rank are co-existent in Japan with a truly democratic spirit probably unequalled in any country except Switzerland or Norway. The reason is probably to be found in the self-respect, and consequent self-esteem, of every Japanese. High and low, rich and poor, are carefully trained from early childhood, and have been trained for untold generations, to treat all and sundry with that courteous consideration that honours the giver as much as the receiver. They have for ages appreciated the truth that rudeness is no sign of manliness, that courtesy of speech and manner are perfectly compatible with self-respect.

REORGANISING THE NATION

WITH the early 'seventies began the great period of

national reorganisation. The most intelligent men in

the land scoured the world in search of everything that might, perchance, be

usefully introduced into Japan, and the best technical advice was sought from

all parts of Europe and America. Hundreds of Occidentals, eminent in their

various callings, were engaged, at handsome salaries, to come to Japan and

guide the footsteps of the infant Power. Japan will never be able fully to

repay the debt she owes to these men. No pillar of stone, no brazen tablet, has

been erected to their memory by the Japanese. They need none. The noblest

monument in the world is that which the Occidental instructors and advisers

have erected for themselves—the New Japan that would not for generations to

come have reached its greatness had it not been for their devoted labours.

With rare insight, the rulers of Japan knew where to

look for the best help; they placed their infant navy under the charge of

British instructors; their army was organised and

trained according to the advice of Germans of the school of Moltke, after the

war of 1870-71 had shown their superiority over the French officers, at whose

feet the Japanese had hitherto sat. The system of national education—it would

perhaps be better to say national instruction—was modelled chiefly by

Americans, while the codification of the laws and the reform of jurisprudence

was the work of Frenchmen and of Germans. In medicine and surgery, too, the

Japanese sought instruction from German men of science. They learnt their

engineering, their chemistry and their electro-technical science at first from

Britons and Americans, but latterly, to a great extent, from Germans.

In many cases the Japanese have improved upon the

instruction imparted to them; in no case have they, so to say, swallowed an

Occidental idea whole. It is a very prevalent, but entirely erroneous, idea

that the Japanese have merely copied from the Occident. They have not adopted

so much as adapted, showing, in most cases, sound judgment in their selection

and great skill in modifying Occidental importations to suit Japanese

conditions.

Besides placing the intelligent youth of the

country—destined to carry on the work of governing the nation, of leading its

forces, of building its means of communication, of increasing its wealth—under

the tuition of the best obtainable foreign knowledge and skill, large numbers

of young men were sent to study abroad. The selection of these students, sent

out sometimes by the Imperial Government, sometimes by their ex-feudal lords,

was in the early days somewhat of a haphazard nature. The results obtained were

therefore scarcely commensurate with the great expense entailed, and the Government

found itself obliged, in the early 'seventies, to recall the majority of the

students who were maintained abroad from the public purse.

With the establishment of excellent facilities for

secondary and higher education in Japan, and the engagement of the best

procurable foreign professors and lecturers, it became possible for students to

complete their studies in the country at a very moderate cost to the

Government, and scarcely any expense to themselves. The disturbing influences

of residence in foreign countries, away from disciplinary control, were thus

obviated. Residence abroad, for the purpose of pursuing the higher branches of

their studies, was thenceforward reserved as a prize, to be obtained only as

the reward of extraordinary ability and application. The students who were sent

abroad under these revised conditions were consequently the pick of the youth

of the country. They achieved excellent results at the principal universities

and technical schools of Europe and America. Their industry, their

intelligence, and their excellent conduct won golden opinions for them and for

their nation. With very few exceptions, they seemed to feel that Japan's

reputation depended on their conduct, and they behaved accordingly. At first

the students, and the numerous officials sent abroad to investigate matters

connected with their particular departments, were much "lionised" by society in Europe and America. No public

function, no evening party, was complete without the presence of one of

"those delightful, interesting Japanese." But society soon tired of

its new toy, and the Japanese abroad found, after a while, that their social

life was restricted within rather narrow limits. In England they found

themselves welcomed chiefly in intellectual circles of rather advanced

opinions. The Philosophical Radicals—a class now practically extinct—took them

under their wing and exerted a considerable influence on the minds of the

students. Those were the days when the Japanese worshipped at the shrine of

Herbert Spencer, and derived their economic principles from the works of John

Stuart Mill. Had the rulers of Japan—for such those students eventually

became—continued to be guided by the principles imbibed abroad in the

'seventies, the course of history might have been different indeed. The great

watchwords that lingered on in Europe and America at that time—Free Trade,

Universal Peace, the Rights of Man, the Brotherhood of Nations, and other

high-sounding terms, as comforting to the minds of the period as "that blessed

word Mesopotamia", were imported into Japan by returning students, whose

influence was so great that the nation seemed likely to adopt their views,

however advanced and subversive.

Impelled by such ideas, Japan might have been a sort

of "proof-butt" for the firing of experimental shots by various

Utopian doctrinaires; it would not have become, in our time, the grimly

efficient power that now makes its stern influence felt even beyond the Far

East. An idealistic Japan, animated by advanced liberal theories, might have

suited the Occident far better; the West has only itself to blame if the Far

East has entered upon a different, more practical, course. It was Germany's

triumph over France that decided Japan's career at the parting of the ways.

Bismarck's policy of "Blood and Iron" established, by its emphatic

success, the principle that "Might is Right"; and the Far East,

always ready to admire strength and power, was not slow in learning the lesson.

From that time dates the powerful German influence

that swayed Japan until 1895, reaching its culminating point in the years

1886-7. The Constitution of Japan, which was originally intended to be

constructed in accordance with the British pattern, was ultimately inspired by

the Constitution of the Kingdom of Prussia, with its restricted popular

liberties. There is some reason in the explanation of this fact offered by a

Japanese statesman: "We went to London to study the British Constitution,

with the intention of taking it as our model, but we could not find it

anywhere; so we had to go to Berlin, where they showed us, with great

readiness, something that we could easily understand, for it was clear,

logical, and set forth plainly in black and white". So Japan participated

in the wave of reaction that swept over Europe in the last thirty years of the

nineteenth century. Protection, Militarism, Nationalism, Imperialism, Colonial

Expansion, replaced the old watch-words: Free Trade, Universal Peace, and the

Brotherhood of Nations, which were relegated to the lumber-room, where cobwebs

were already accumulating over the Rights of Man.

Whatever one's opinions may be, one must admit that

Japan took a wise course in devoting her energies primarily to making herself

immensely strong by sea and land, thus acquiring that sense of absolute

security indispensable to national development. It is quite certain that no

amount of progress in education, in arts, science, commerce, and industries, no

increase, however wonderful, in the institutions for promoting the welfare of

the population, would have earned for Japan the position among nations that she

has made for herself by the use of her keen-edged sword. "Pity 'tis, 'tis

true," but we need only carry our thoughts back to the Occidental opinion

of Japan before her victory over China in 1893 to realise that it was her military prowess that opened the eyes of the purblind West to

the fact that a new Great Power was arising in the Far East. When the makers of

New Japan set about constituting the armed forces that were to make the reorganised empire safe and, later, to "carry its

glory beyond the seas"—to use a Japanese phrase—they might easily have

adopted the system of voluntary service that still obtains in the British

Empire and in the United States of America, with this difference, that the

question of pay would have been a minor consideration.

They had ready to their hands, in 1868, about half a

million males of the military class—Samurai—hereditary warriors, the kind of

material any Occidental Minister of War would have given a year's budget to

have at his disposal. These born fighters would have flocked to the standards,

considering, as they did, that the profession of arms, even in its lowest

ranks, was the only one fit for a gentleman to follow.

But the makers of the new empire were wise men; they

decided that the pick of Japan's manhood, irrespective of class or wealth,

should man Japan's warships and fill the ranks of her Army. By so doing, they

not only ensured that their forces would combine intelligence with physical vigour, skill with strength, but they also prepared for the

nation a magnificent training-school where all the best elements of the

population could be further improved by being taught the great lessons of

devotion to the public weal, of self-sacrifice, of discipline, of order and

cleanliness—the last a "gilding of fine gold" in the case of such a

cleanly people.

So the law of universal naval or military service was

instituted, in 1873, placing every able-bodied Japanese male at the disposal of

his country from the age of seventeen to that of forty. In practice, only the

physically and mentally fittest are selected, joining the colours at twenty years of age, for an active service of three years if in the Army,

four in the Navy—the active service of the infantry of the line is about to be

reduced to two years. This is followed by service in the Reserve, for four

years in the Army, or seven years in the Navy, with periodical recalls to the colours for training and manoeuvres.

On leaving the Reserve, a Japanese is still liable during ten years to be

called upon for what is called "Depot Service" at home or abroad, in

case of extreme urgency. Not only are these military obligations cheerfully

borne by all classes—a premium is offered to young men of higher education by

allowing them the privilege of a reduction of their active service to one year,

during which they must qualify themselves for the duties of officers in the

Reserve—but they are eagerly entered upon and considered a personal honour.

The formation of this truly national army aroused

misgivings in the minds of many of the Samurai, who could not bring themselves

to believe that the Heimin, the common people, who

had hitherto been denied the privilege of bearing arms, could ever be made into

soldiers. Their opposition to the enrolment of peasants, craftsmen, and traders

had an element of personal interest, for military service, ashore or afloat,

seemed the only occupation open to the two-sworded men now that feudalism was abolished; had the armed forces been recruited

entirely from them, as in the past, their future would not have appeared so

gloomy.

It must be borne in mind that these feudal retainers

had, under the old system, little need of care for the morrow. They and their

families were kept by their feudal lords. Some of them obtained their pay—for

such it really was—from the rents of lands assigned to their ancestors by their

feudal masters, in return for military service; the majority received their

salary in rice. Some enjoyed pensions for life, as a reward for special

services. With the disestablishment of the Han, or feudal clan governments,

these pensions, and the whole system of feudal service, were bound to

terminate, but the Imperial Government recognised that the Samurai had a vested right that could not be ignored, so they decreed,

in 1873, that any Samurai who desired to commute his hereditary income could do

so, receiving the commutation, equivalent to six years' income, half in cash

and half in Government Bonds, bearing 8 per cent, interest; life- pensioners

could commute for the equivalent of four years' income, in the same proportion

of cash and bonds. In 1876 this commutation was made compulsory.

It will be of interest to Socialists to note that,

soon after this distribution of capital amongst the Samurai, many of them were

found to have fallen into great poverty. The energetic and clever ones made

excellent use of the means at their disposal. Equipped with the capacity for

ruling that was the result of their hereditary high position and privileges,

they managed to remain in the upper strata of society, and they virtually rule

Japan in our time. The less capable, the spendthrifts, the careless ones, sank

from their high estate and became gradually merged in the ranks of the common

people. Some of them are drawing jinrikisha in the streets of Tokio. A great number naturally entered the armed forces,

but as they could not all be officers, many of them had to be content with

warrant rank or non-commissioned ratings. The admirable police force is

recruited entirely from Samurai, or, as they are called, since 1878, Shi-zoku. The misgivings of the knightly class as to the

efficiency of the new Army, the majority of whose men were not Samurai, were

soon to be dispelled by its prowess in war, although its early victories were

gained over its fellow-countrymen, except in one case, and in that over

Formosan savages.

The new military law had only been in operation one

year when, in 1874, the troops had to be employed in quelling an insurrection

in the province of Saga, where a number of the discontented attempted to oppose

by force the great changes that were being introduced. In the same year, New

Japan sent its first warlike expedition across the seas; the savage aborigines

of Formosa were chastised for the massacre of some shipwrecked Japanese

fishermen, China, at that time the owner of the island, being totally unable to

control its unruly subjects in those parts. The expedition, the expense whereof

was ultimately refunded by China, provided but an unsatisfactory test of the

efficiency of the new army; the rugged, mountainous nature of the country

presented great obstacles to the movement of troops, but the fighting was

insignificant. Three years later, in 1877, the new Imperial forces were to

come, with brilliant success, through a very severe ordeal. The ultra-conservative

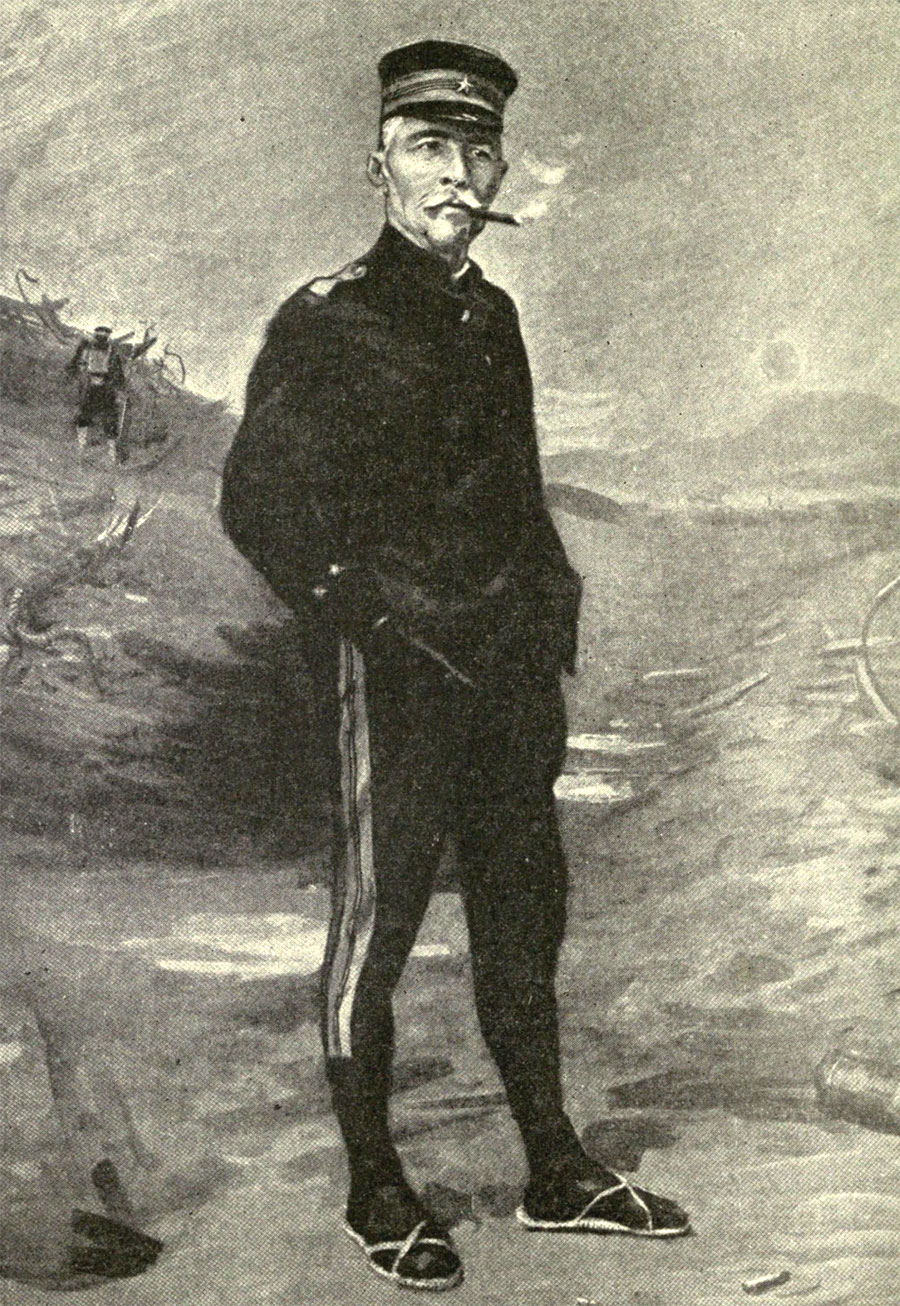

party in the powerful Satsuma clan, under the leadership of the famous General Saigo Takamori, the idol of the

Samurai, the very incarnation of the Japanese knightly spirit, had determined

to possess themselves of the Emperor's person, quite in the grand manner of Old

Japan, and to save him, so they said, from the evil counsellors who were

ruining the country with their absurd new-fangled notions. The truth is that

the High Toryism of these men of Satsuma was not unmixed with personal interests.

They considered that the Imperialists of other clans—and especially those of

Cho-shu and of Tosa—had

secured an undue share of the loaves and fishes. Saigo,

who had retired to Kagoshima in the sulks, had organised a vast system of military schools, at which 20,000 young Samurai were being

trained for war and imbued with deadly hatred of the Government.

After several ineffectual attempts on the part of

emissaries of the Government to come to an amicable understanding with Saigo, he began a march, at the head of 14,000 men, up the

west coast of Kiu-shu, with the intention of reaching Tokio. The great obstacle in his way was the ancient

castle of Kumamoto, built by the famous General Kato Kiyomasa,

after his Korean expedition at the end of the sixteenth century. This was

garrisoned by a force of between two and three thousand Imperial troops under

General Tani. Saigo made a

furious onslaught on the fortress, which was most gallantly defended, and

delayed his advance for several weeks. This gave the Government time to organise a large force, under the Imperial Prince Arisugawa. The preparation of the expedition was entrusted,

strangely enough, to General Saigo Tsugumichi, a younger brother of the great rebel. By

keeping him at headquarters at Tokio, busy with

matters of equipment and organisation, he was given

the opportunity of displaying his loyalty to the Emperor, without actually

taking the field against his brother. The Imperial forces relieved Kumamoto in

the nick of time, for the garrison was reduced to great straits. There was

desperate fighting, the besiegers were driven off and retreated towards the

east coast, and after a succession of desperate actions, in which they were

outnumbered and outmanoeuvred, they made a last stand

at Nobeoka, in the north-eastern corner of Hiuga.

Recognising the hopeless nature of their position, Saigo, with about two hundred of his adherents, broke

through the Imperial lines and escaped to Kagoshima. The bulk of his army

surrendered on August 19th, 1877; they had begun their northward march in the

middle of February of the same year. Saigo and his

devoted little band entrenched themselves on the hill Shiro-yama,

above Kagoshima, where they were surrounded and subjected to bombardment day

and night. The great rebel, wounded in the thigh, and seeing that all hope was

gone, retired into a cave, and committed hara-kiri, after having requested one

of his trusted lieutenants to behead him, which his friend promptly did, as the

last service he could render to his revered leader. When the Imperial troops

discovered the remains of the little band of heroes—the few who had not been

killed, some of them mere boys, had committed hara-kiri—they gave them decent

burial. Admiral Kawamura himself reverently washed the head of his dead friend

and fellow-clansman Saigo, whose memory is venerated

to this day as that of a brave knight and noble gentleman, who paid for his

misguided zeal with his life. A monument has been erected in Tokio to his memory, to which even the Imperial Court paid

homage, his honours having been posthumously restored

in 1890.

The Satsuma rebellion of 1877 was the last struggle of

moribund feudalism. It taught two great lessons: the powerlessness of the

ancient weapons, even though wielded by the bravest of the brave, when opposed

to modern armaments and Occidental tactics, drill, and organisation;

and the splendid fighting capacity of the common people when led by Samurai. It

could no longer be maintained by the Conservatives that the Heimin troops could never prevail against the hereditary warriors. The

newly-introduced universal military service was thus fully justified by its

works, and there could be no more question of restricting the army to the old

warrior class. The Satsuma clan soon settled down to peaceful pursuits, but it

continues to play a leading part in the affairs of the nation, supplying more

officers to the Navy and the Army than any other of the old clans, thus forming

the backbone of the strong Military Party.

In the early 'seventies, whilst the foundations of the

Imperial forces were being laid, Japan was, towards the outer world, much in

the same condition as a shellfish deprived of its shell. Fully cognisant of the danger they ran whilst the country was in

a state of transition, preparing its new armour, the

wise statesmen of Japan exercised remarkable prudence in dealing with such

international questions as might have involved them in war. It was thus they

came to an agreement, in 1875, with Russia, by which they exchanged such parts

of the island of Saghalin as were considered within

their sphere of influence for the long chain of the barren Kurile Islands (in

Japanese, Chi-shima, or "Thousand

Islands"). They were well aware of the bad bargain they were making, but

considered it preferable to a breach with Russia at a time when they were not

in a position to oppose a great Power with any chance of success. Patiently

biding their time, as is the wont of Orientals, some of those statesmen have

lived to see, thirty years later, the southern part of Saghalin restored to Japan, whilst the Kuriles remain in her possession.

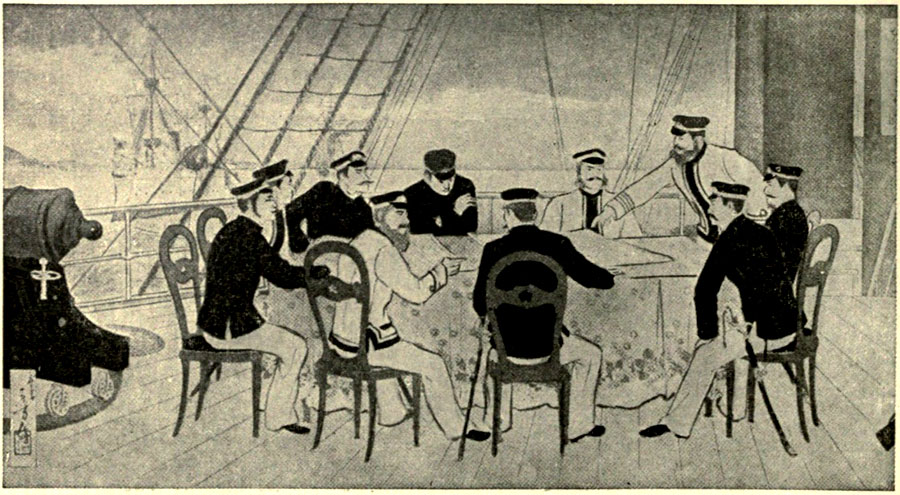

They behaved with similar prudence when, in January,

1876, they found themselves compelled to despatch a

small expedition, under General Kuroda, to Korea, to demand satisfaction from

the "Hermit Kingdom" for an unprovoked attack upon a Japanese ship

calling for coal and provisions at a Korean port. The High Tories, especially

those of Satsuma, clamoured for immediate chastisement

of the Koreans, who had already incurred their wrath by neglecting to send a

congratulatory mission, as ancient usage demanded, on the accession of the

Emperor in 1867. The rulers of Japan wisely preferred to settle the matter by

diplomacy, and concluded a treaty with Korea, safeguarding the important

Japanese interests in that country. In 1879, the Riu-kiu,

or Loo-choo, Islands, the suzerainty over which had long been claimed both by

China and by Japan, were incorporated in the latter empire, as the Prefecture

of Okinawa, after diplomatic negotiations conducted with great skill. The

period from the abolition of feudalism in 1871 to 1887 was one of tremendous

activity and restless effort in the direction of reform. A great wave of

foreign influence swept over the land, culminating in 1873 and in the years

between 1885 and 1887, when the movement for "Europeanisation" became

a perfect rage, affecting not only administrative methods and national

institutions but social life. Many of the foreign features introduced into

public and private life in that epoch took Arm root, being recognised as great improvements on the old order of things; but every one of them

suffered a "sea-change" in crossing the ocean, being adapted,

generally with great skill, to national requirements, and coated, so to say,

with a layer of fine Japanese lacquer. Other importations, hailed at first with

enthusiasm, proved, by the experience of practical use, unsuited to Japanese

conditions, and were dropped as hastily as they had been taken up, leaving no

trace behind.

In 1871, the defunct feudal system was replaced by a centralised bureaucratic administration. The Daimiyo, being thus deprived of the last remnant of

authority that remained to them whilst they had been placed in charge of their

former clans, were "compensated" by the receipt of fixed incomes,

amounting to one-tenth of their former revenues. This arrangement, apparently unfavourable to the ex-feudal nobility, was in reality much

to the advantage of most of them, who were now relieved of the heavy charges

they had formerly borne for the expenses of the government of their fiefs and

the support of the Samurai families. The large sum that had to be raised by the

Government for the commutation, already described, of the pensions, or

salaries, of the Samurai class, was obtained by means of public loans.

The first foreign loan was negotiated in London, in

1870, bearing interest at 9 per cent., the proceeds being employed chiefly for

the construction of the first railway, between Tokio and Yokohama (eighteen miles), opened for traffic in 1872, and of that

between Osaka and Kobé. At the end of 1913, the total

mileage open to traffic was 5,606. The nationalisation of all the railways was decided upon in 1906 and has been gradually effected.

The State began purchasing the private lines, starting with seventeen

companies, whose property was to be bought within ten years from March, 1906,

and paid for with bonds bearing interest at 5 per cent., the purchase-price

being calculated thus: the average rate of profit, over cost of construction,

during six half-yearly terms (the first half of 1902, first and second halves

of 1903 and 1904, and the first half of 1905), is multiplied by twenty; the

figure thus obtained is then added to the cost of construction up to the date

of purchase and to the cost price of rolling stock and stores in hand at that

time. At the beginning of the fiscal year 1913—that is, in April of that

year—the National Debt of Japan amounted to $1,250,000,000 of which total $713,841,450

was owing to foreign creditors. The war with Russia increased the National Debt

of Japan from $267,729,500 by $765,141,500 to nearly $1,000,000,000.

These figures, those for railway mileage, and those

for the national indebtedness, bear eloquent testimony to the enormous increase

in facilities for internal communications and in the extension of the national

credit. In every direction the same astonishing development may be traced since

the Great Change in 1868. The system of lighting the coasts of Japan, now a

pattern for the maritime nations, dates its inception from 1870, the year which

also saw the birth of the network of telegraph lines that now covers the whole

empire. In 1871, the ancient method of conveying letters by postrunners,

a wonderfully speedy one considering its primitive nature, was supplanted by

the beginnings of a Postal Administration that has reached a high degree of

efficiency, handling, at the end of the fiscal year 1912, at 7166 post and

telegraph offices, 1,677,000,000 articles of ordinary mail matter. The total

length of telegraph lines amounted to 295,000 miles in 1913. The Imperial Mint

at Osaka was established, with British technical assistance, in 1871.

The first railway was opened, as already mentioned, in

1872, the year that also saw the birth of the newspaper press, with the

appearance of the first number of the Nisshin Shinjishi,

a periodical started by an Englishman named Black. There had been attempts at

the publication of newspapers, of a sort, in 1871, and as far back as 1864-5;

but Mr. Black's venture was the first serious step taken to provide the nation

permanently with something better than the news-sheets hawked about the streets

by newsvendors called yomi-uri, who bawled out their

wares, usually lurid accounts of some horrible murder, a fire or an earthquake,

very much in the style of the London newsboy's "'Orful slaughter!" of

bygone days. These roughly-printed broadsheets were issued spasmodically,

whenever some important event, or some crime sure to excite the popular

imagination, seemed likely to render their sale profitable.

The publication of Mr. Black's little journal was

followed by the establishment of purely Japanese journalistic undertakings—the Nichi Nichi Simbun (Daily News) in 1872, which still flourishes under the same title. The number

of periodicals has continued to increase steadily, especially since the

amendment of the Press Laws, in 1890, substituting the regular process of law

for the arbitrary jurisdiction of the censorship. Every periodical must have a

responsible editor or publisher, and any daily paper or other periodical

dealing with current politics must deposit with the authorities a sum, ranging

from $500 downwards, as security for good behaviour,

to cover eventual fines. The price of one of the Tokio dailies is as high as one cent and a quarter (2'5 sen)

; all the others cost half a cent (one sen). They are

all issued in the morning, except the only Tokio newspaper written, edited, and published in English by Japanese, which appears

in the evening. The charge for advertisements in the Japanese Press is from

18c. to 30c. per line of about twenty words. In 1903 there were 1,499

newspapers and other periodicals published in Japan, whereof seven were

English newspapers written, edited, and owned by foreigners, British or

American, and published in the foreign settlements at the late Treaty Ports,

the most important and oldest established being the Japan Mail, which

circulates throughout the country, and is widely read by Europeans interested

in Japanese affairs. This excellent periodical was established in 1865. Of the

nearly fifteen hundred vernacular periodicals, some are of high standing and

deserving of all praise. Many of the others, unfortunately, take the

"Yellow Press" of America and England as their model, and are

correspondingly mischievous and degrading.

Nearly every Japanese adult, and practically all the

young people of both sexes, are able to read, and make great use of this

ability. Even the sturdy men who do the work of horses, drawing the jinrikisha,

the cabs of Japan, seem to occupy the greater portion of their unemployed hours

in the daytime in reading newspapers or cheap, popular books. The craftsmen and

peasants are kept well informed of current events, and take an intelligent

interest in the affairs of the nation, the farmers especially often displaying

sound common-sense when they discuss, as they often do when the day's work is

over, the topics of the day. The greatest need in connection with the Press in

Japan is undoubtedly a more drastic law of libel, to check the slanderous

scandal that at present disfigures the "Personal" columns of all but

the very best journals, pandering to the national love of ill-natured gossip

about those in high official positions or otherwise prominently before the

public.

The year 1872 was also memorable for the establishment

of the first Protestant church, and for the foundation of the Imperial

University of Tokio. In the same year a special

embassy, with the former Court Noble, Iwakura, a

former Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs, at its head, was sent

out, first to the United States, thence to England and the Continent of Europe,

nominally "to communicate to the Governments of the Treaty Powers details

of the internal history of Japan during the years preceding the revolution of

1868, and the restoration of the Imperial power, to explain fully the actual

state of affairs and the future policy of the Japanese Government, and to study

the institutions of other countries, their laws, commerce and educational

methods, as well as their naval and military systems". The real object of

this embassy was to endeavour to obtain a revision of

the treaties, whereby the "Extra-territoriality Clause," withdrawing

foreigners from Japanese jurisdiction and placing them under that of the

representatives of their own nations, would be abrogated, thus removing a sharp

thorn from the Japanese national body. To such a proud, sensitive people, the

idea of foreign jurisdiction established on their territory was unbearably

galling. The embassy failed to secure the abrogation of the obnoxious clause,

and Japan had to wait twenty-seven years, till 1899, for the nations, Britain

leading, to treat her, for the first time, on terms of equality by consenting

to abandon the privileged position of their subjects and placing them under the

jurisdiction of the Japanese courts. The next year, 1873, was memorable for two

acts of progress—the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, and, more important,

the repeal of the edicts against Christianity that were still in vigour, in spite of repeated unofficial assurances that no

Japanese should suffer for his adherence to that faith. One of the first edicts

of the Imperial Government, after its establishment in 1868, ran as follows :

"The evil sect called Christian is strictly prohibited. Suspected persons

should be reported to the proper officials, and reward will be given for

detection." The immediate cause of this intolerant order was the

discovery, at Urakami, a village in the mountains

near Nagasaki, of a small community who had retained, in secret, some faint

reminiscences of the Iberian Catholicism openly practised by their forefathers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is said

that about 4,000 people in the district still carefully cherished the shreds of

doctrine and of ritual that had been thus wonderfully preserved, at the risk of

torture and death. In June, 1868, the Government ordered that all native

Christians who would not recant should be deported to different provinces as

dangerous persons, and put in charge of various feudal lords. The foreign

diplomatic representatives protested vigorously and successfully; the

Government, after striving to excuse its conduct by alleging the intense feeling

of the nation against Christianity, ultimately restored these faithful ones to

their homes. As already stated, in 1873 Christianity was no longer a misdemeanour, and there began the reign of toleration which

culminated in the right, assured to all Japanese subjects by the Constitution

of 1889, of freedom of religious belief "within limits not prejudicial to

peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects."

This religious tolerance is, indeed, in accordance

with the real feeling of the Japanese in such matters. Having, as a rule, no

deep religious sentiment, as Occidentals know it, they pass easily from one

creed to another, many of them belonging to more than one religious

denomination, at all events as far as the outward observances are concerned,

and the majority of those educated in the higher schools being practically

Agnostics. The fact is that the Japanese of our time have been, and still are,

so busy acquiring the Occidental knowledge necessary for the transformation of

their country into the great naval, military, commercial, and industrial power

of the Far East, that, as they themselves have frequently stated, "they

have had no time to devote to religious questions." Nevertheless, whether

they be willing to admit it or not, the men of New Japan have been greatly

under the influence of Christian ideas, propagated by the numerous missionaries

within their borders or imbibed by Japanese students residence abroad,

especially in the early years of the present era. Although the number of

natives professing Christianity is not very great, amounting only to about

150,000 of all denominations out of a population of nearly 53,000,000, they

exercise a considerable influence, several of them occupying some of the

highest posts.

The rights assured to the Japanese by their

Constitution are borrowed from the liberties enjoyed by the citizens of

Occidental nations, whose laws are inspired by the spirit of Christianity, if

their policy be often sadly at variance therewith. In one respect Christianity

has, fortunately, succeeded in effecting a marked change in the Japanese: the

spirit of mercy so brilliantly in evidence in the treatment of defeated

enemies, and of the sick and wounded in war and the weak and suffering in

peace, especially in the humane work of that most admirable Japanese

institution, the Red Cross Society of Japan, with its membership of over a

million — all this is undoubtedly the outcome of Christian influence prevailing

over the old savage ruthlessness of the Japanese character. A generation or two

will have to pass before Christianity can totally eradicate the cruelty, the

deceit, and the spirit of revenge from Japanese natures—it has not yet, after

many centuries, succeeded in eliminating them from the bosom of some Occidental

nations; but there are good grounds for hoping that the Japanese of a not very

distant future will let Christianity accomplish, in that respect, what nearly

fourteen centuries of Buddhism have failed to do. Whatever form of Christianity

may ultimately claim the adherence of a large proportion of the Japanese

people—and they are, at present, bewildered by the multiplicity of "one

and only" direct routes to heaven offered to them— it will not be the

Christianity of Rome, nor of Canterbury, nor of Moscow, nor of the Salvation

Army; it will surely be a Japanese Christianity, and, perchance, nearer than

any of the others to the Christianity of Christ.

Meanwhile, the State religion of Japan is the ancient,

truly national, faith known as Shinto, meaning "The Way of the Gods",

a mixture of primitive Nature-worship and of the cult of the Kami, the spirits

of the Powers of Nature and the spirits of deified heroes, from whom the

Japanese claim descent—the noble families directly, the others in a more or less

vague way. It can hardly be termed a religion, as it has neither dogma, creed,

nor commandments. Its principal idea, which forms its sole ethical teaching,

is, roughly expressed, that, the nature of mankind being originally good, every

man may safely be left to his own devices, provided he always bear in mind the

duty of so regulating his conduct as to "make the faces of his ancestors

to shine with glory" and never to do aught that would cause them to blush.

The makers of New Japan sought to re-establish this ancient

cult in its original purity, cleansing it of the Buddhist overgrowth that had

accumulated since the cunning Buddhist priests of the Middle Ages had virtually

"annexed" Shinto, providentially discovering that the Kami of the

aboriginal faith were "avatars," or incarnations (in Japanese, gon-gen, or temporary manifestations) of the myriad Buddhas

who lived in this world and are now in Nirvana. The reformers, who had

succeeded in abolishing the "usurpation" that had so long flourished

as the Shogunate, were keen in scenting out usurpations. Surely, the mixture of

the original national cult with Buddhism, the creed favoured by the Shogunate, producing the strange composite religion known as Riyobu Shinto, or Shin-Butsu Gattai—"amalgamation of Shinto and Buddhism"—was a usurpation not

further to be tolerated.

So the reformers proceeded to disestablish Buddhism

with a thoroughness approaching that of Henry VIII in his suppression of

monastic institutions. The gorgeous paraphernalia of Buddhism, inspired by the

ornate art of ancient India, was cleared out of the annexed Shinto temples (Jin-ja), which were restored to their original austere

simplicity, resembling that of a bicycle-shed or a motor garage, and many

Buddhist monasteries were shorn of their fat revenues. The imported faith had

never succeeded in gaining a footing in Izumo, the "Land of the Gods"

(Kami-no Kuni), where the influence of ancient

tradition, making that district the scene of so many purely Japanese

mythological events, was too strong to be overcome, nor in Satsuma, whose

warlike people naturally looked upon meek and mild Buddhism as a creed unfit

for warriors; in the rest of Japan the disestablishment of the Indian religion,

and the Buddhism return to pure Shinto, was a serious matter.

That it was so easily accomplished indicates the

strength of the national movement, striving to reestablish the supreme

influence of the sacred Imperial power.

Like other creeds, Buddhism derived benefit from

persecution; a notable revival has taken place in that religion of late years.

Strangely enough, in its efforts to regain its lost predominance in Japan, it

has taken a lesson from the activity of the Christian missionaries. Every

feature that distinguishes missionary enterprise in the Far East has been