|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

THE VIOLIN. ITS FAMOUS MAKERS AND THEIR IMITATORS

Anecdotes and Miscellanea connected with the Violin

The important part

played by the renowned Champion Crowdero in Butler's inimitable

satire has never failed to give keen enjoyment to all lovers of

wit and humour. This being so, his exploits should be doubly appreciated

by the votaries of the Fiddle, since it was he who valiantly defended

the cause of Fiddling against the attacks of Hudibras—

The absurdities into

which the genius of Cervantes hurried Don Quixote and Sancho served

to moderate the extravagances of knight-errantry. The adventures

of Hudibras and Ralpho, undertaken to extinguish the sports and

pastimes of the people, aided greatly in staying the hand of fanaticism,

which had suppressed all stage plays and interludes as "condemned

by ancient heathens, and by no means to be tolerated among professors

of the Christian religion." With Crowdero we

are taken back upwards of two centuries in the history of the Violin;

from times wherein it is held in the highest esteem and admiration,

to days when it was regarded with contempt and ridicule. Crowdero

(so called from crowd, a Fiddle) was the fictitious

name for one Jackson, a milliner, who lived in the New Exchange,

in the Strand. He had served with the Roundheads, and lost a leg,

which brought him into reduced circumstances, until he was obliged

to Fiddle from one alehouse to another for his existence. Hudibras— On stirrup-side, he gaz'd about Ralpho rode on, with no less

speed And now the field of death, the

lists, In name of King and Parliament

...

first surrender This said he clapped his hand

on sword, He drew up all his force into The Knight, with all its weight,

fell down Like a feather bed

betwixt a wall Crowdero only kept the field, In haste he snatch'd the wooden

limb Vowing to be reveng'd, for breach When Ralpho thrust himself between, ... but first our care To rouse him from lethargic dump,

...

The foe, for dread ... The Knight began to rouse, Will you employ your conq'ring

sword ... I think it better far He liked the squire's advice,

and soon Ralpho dispatched with speedy

haste, The Squire in state rode on before, Thither arriv'd, th' advent'rous

Knight On top of this there is a spire

GEORGE HERBERT'S

REFERENCES TO MUSIC. George Herbert, poet

and divine, said of music, "That it did relieve his drooping

spirits, compose his distracted thoughts, and raised his weary soul

so far above earth, that it gave him an earnest of the joys of heaven

before he possessed them." His worthy biographer, Izaak Walton,

tells us—"His chiefest recreation was music, in which

heavenly art he was a most excellent master, and did himself compose

many divine hymns and anthems, which he set and sung to his Lute

or Viol; and though he was a lover of retiredness, yet his love

to music was such that he went usually twice every week, on certain

appointed days, to the Cathedral Church in Salisbury, and at his

return would say, 'That his time spent in prayer and Cathedral music

elevated his soul, and was his heaven upon earth.' But before his

return thence to Bemerton, he would usually sing and play his part

at an appointed private music meeting; and, to justify this practice,

he would often say, 'Religion does not banish mirth, but only moderates

and sets rules to it.'" In walking to Salisbury

upon one occasion to attend his usual music meeting, George Herbert

saw a poor man with a poor horse that was fallen under his load.

He helped the man to unload and re-load; the poor man blessed him

for it, and he blessed the poor man. Upon reaching his musical friends

at Salisbury they were surprised to see him so soiled and discomposed;

but he told them the occasion, and when one of the company said

to him "He had disparaged himself by so dirty an employment,"

his answer was, "That the thought of what he had done would

prove music to him at midnight; and that the omission of it would

have upbraided and made discord in his conscience whenever he should

pass by that place; 'for if I be bound to pray for all that be in

distress, I am sure that I am bound, so far as it is in my power,

to practise what I pray for; and though I do not wish for the like

occasion every day, yet let me tell you, I would not willingly pass

one day of my life without comforting a sad soul, or showing mercy;

and I praise God for this occasion; and now let us tune our instruments.'" Herbert's love of

imagery was often curious and startling. In singing of "Easter"

he said— "Awake my lute and struggle

for thy part The Cross taught all wood to

resound His name, His stretched sinews taught all

strings, what key

Pleasant and

long: Or since all music is but three

parts vied The Sunday before

the death of "Holy George Herbert," Izaak Walton says,

"he rose suddenly from his bed, or couch, called for one of

his instruments, took it into his hand and said— "My God, my God, my music

shall find Thee; And every string And having tuned it, he played

and sung—

The thought to which

Herbert has given expression in his lines on Easter—that "All

music is but three parts vied and multiplied"—was also

in the mind of Christopher Simpson, who, in his work on "The

Division Viol," 1659, uses it as a musical illustration of

the doctrine of Trinity in Unity. He says: "I cannot but wonder,

even to amazement, that from no more than three concords (with some

intervening discords) there should arise such an infinite variety,

as all the music that ever has been, or ever shall be, composed.

When I further consider that these sounds, placed by the interval

of a third one above another, do constitute one entire harmony,

which governs and comprises all the sounds that by art or imagination

can be joined together in musical concordance, that,

I cannot but think a significant emblem of that Supreme and Incomprehensible

Three in One, governing, comprising, and disposing the whole machine

of the world, with all its included parts, in a most perfect and

stupendous harmony." It is interesting

to notice an earlier and remarkable allusion to the union of sound

from the pen of Shakespeare—

VIOLINS FROM A MEDICAL

POINT OF VIEW. "Music and the

sounds of instruments—says the lively Vigneul de Marville—contribute

to the health of the body and the mind; they assist the circulation

of the blood, they dissipate vapours, and open the vessels, so that

the action of perspiration is freer. He tells the story of a person

of distinction, who assured him that once being suddenly seized

by violent illness, instead of a consultation of physicians, he

immediately called a band of musicians, and their Violins played

so well in his inside that his bowels became perfectly in tune,

and in a few hours were harmoniously becalmed."—D'Israeli's "Curiosities

of Literature." Dr. Abercrombie recommends

"Careful classification of the insane, so that the mild and

peaceful melancholic may not be harassed by the ravings of the maniac.

The importance of this is obvious; but of still greater importance,"

he continues, "it will probably be to watch the first dawnings

of reason, and instantly to remove from the patient all associates

by whom his mind might be again bewildered." The following case,

mentioned by Pinel, is certainly an extreme one, but much important

reflection arises out of it:— "A musician

confined in the Bicêtre, as one of the first symptoms of returning

reason, made some slight allusion to his favourite instrument. It

was immediately procured for him; he occupied himself with music

for several hours every day, and his convalescence seemed to be

advancing rapidly. But he was then, unfortunately, allowed to come

frequently in contact with a furious maniac, by meeting him in the

gardens. The musician's mind was unhinged; his Violin was

destroyed; and he fell back into a state of insanity which

was considered as confirmed and hopeless."—Abercrombie's "Intellectual

Powers." "A MUSICIAN is like an Echo,

a retail dealer in sounds. As Diana is the goddess of the silver

bow, so is he the Lord of the wooden one; he has a hundred strings

in his bow; other people are bow-legged, he is bow-armed;

and though armed with a bow he has no skill in archery. He plays

with cat-gut and Kit-Fiddle. His fingers

and arms run a constant race; the former would run away from him

did not a bridge interpose and oblige him to pay toll. He can distinguish

sounds as other men distinguish colours. His companions are crotchets

and quavers. Time will never be a match for him, for he beats him

most unmercifully. He runs after an Italian air open-mouthed, with

as much eagerness as some fools have sought the philosopher's stone.

He can bring a tune over the seas, and thinks it more excellent

because far-fetched. His most admired domestics are Soprano, Siciliano,

Andantino, and all the Anos and Inos that constitute the musical

science. He can scrape, scratch, shake, diminish, increase, flourish,

&c.; and he is so delighted with the sound of his own Viol,

that an ass would sooner lend his ears to anything than to him;

and as a dog shakes a pig, so does he shake a note by the

ear, and never lets it go till he makes it squeak. He is a walking

pillory, and crucifies more ears than a dozen standing ones. He

often involves himself in dark and intricate passages, till he is

put to a shift, and obliged to get out of a scrape—by

scraping. His Viol has the effect of a Scotch Fiddle,

for it irritates his hearers, and puts them to the itch. He tears

his audience in various ways, as I do this subject; and as I wear

away my pen, so does he wear away the strings

of his Fiddle. There is no medium to him; he is either in a flat

or a sharp key, though both are natural to him.

He deals in third minors, and major thirds; proves a turncoat, and

is often in the majority and the minority in the course of a few

minutes. He runs over the flat as often as any

Newmarket racehorse; both meet the same fate, as they usually terminate

in a cadence; the difference is—one is driven

by the whip-hand, the other by the bow-arm;

one deals in stakado, the other in staccato.

As a thoroughbred hound discovers, by instinct, his game from all

other animals, so an experienced musician feels the

compositions of Handel or Corelli.—Yours, TIMOTHY CATGUT,

Stamford."—Monthly Mirror. ORIGIN OF TARTINI'S

"DEVIL'S SONATA." The following interesting

account of this marvellous composition was given by Tartini to M.

de Lalande, the celebrated astronomer:— "One night in

the year 1713, I dreamed that I had made a compact with his Satanic

Majesty, by which he was received into my service. Everything succeeded

to the utmost of my desire, and my every wish was anticipated by

this my new domestic. I thought that on taking up my Violin to practise,

I jocosely asked him if he could play on that instrument. He answered

that he believed he was able to pick out a tune; and then, to my

astonishment, began to play a sonata, so strange and yet so beautiful,

and executed in so masterly a manner, that I had never in my life

heard anything so exquisite. So great was my amazement that I could

scarcely breathe. Awakened by the violent emotion, I instantly seized

my Violin, in the hope of being able to catch some part of the ravishing

melody which I had just heard, but all in vain. The piece which

I composed according to my scattered recollection is, it is true,

the best of my works. I have called it the 'Sonata del Diavolo,'

but it is so far inferior to the one I heard in my dream, that I

should have dashed my Violin into a thousand pieces, and given up

music for ever, had it been possible to deprive myself of the enjoyments

which I derive from it."

In the "Reminiscences

of Michael Kelly" we are told that in the year 1779 Kelly was

at Florence, and that he was present at a concert given at the residence

of Lord Cowper, where, he says, he had "the gratification of

hearing a sonata on the Violin played by the great Nardini; though

very far advanced in years, he played divinely. Lord Cowper requested

him to play the popular sonata, composed by his master, Tartini,

called the 'Devil's Sonata.' Mr. Jackson, an English gentleman present,

asked Nardini whether the anecdote relative to this piece of music

was true. Nardini answered that 'he had frequently heard Tartini

relate the circumstance,' and at once gave an account of the composition,

in accordance with that furnished by M. de Lalande." DR. JOHNSON AND THE

VIOLIN. "Dr. Johnson

was observed by a musical friend of his to be extremely inattentive

at a concert, whilst a celebrated solo-player was running up the

divisions and sub-divisions of notes upon his Violin. His friend,

to induce him to take greater notice of what was going on, told

him how extremely difficult it was. 'Difficult do you call it, sir?'

replied the Doctor; 'I wish it were impossible.'"—Seward's "Anecdotes

of Dr. Johnson." "In the evening

our gentleman farmer and two others entertained themselves and the

company with a great number of tunes on the Fiddle. Johnson desired

to have 'Let ambition fire thy mind' played over again, and appeared

to give a patient attention to it; though he owned to me that he

was very insensible to the power of music. I told him that it affected

me to such a degree, as often to agitate my nerves painfully, producing

in my mind alternate sensations of pathetic dejection, so that I

was ready to shed tears; and of daring resolution, so that I was

inclined to rush into the thickest part of the battle. 'Sir,' said

he, 'I should never hear it if it made me such a fool.'"—Boswell's "Life

of Johnson." DR. JOHNSON ON THE

DIFFICULTY OF PLAYING THE FIDDLE. "Goldsmith:

'I spoke of Mr. Harris, of Salisbury, as being a very learned man,

and in particular an eminent Grecian.' "Johnson:

'I am not sure of that. His friends give him out as such, but I

know not who of his friends are able to judge of it.' "Goldsmith:

'He is what is much better; he is a worthy, humane man.' "Johnson:

'Nay, sir, that is not to the purpose of our argument; that will

as much prove that he can play upon the Fiddle as well as Giardini,

as that he is an eminent Grecian.' "Goldsmith:

'The greatest musical performers have but small emoluments; Giardini,

I am told, does not get above seven hundred a year.' "Johnson:

'That is indeed but little for a man to get, who does best that

which so many endeavour to do. There is nothing, I think, in which

the power of art is shown so much as in playing on the Fiddle. In

all other things we can do something at first; any man will forge

a bar of iron if you give him a hammer; not so well as a smith,

but tolerably; and make a box, though a clumsy one; but give him

a Fiddle and a Fiddlestick, and he can do nothing.'"—Boswell's "Life

of Johnson." DR. JOHNSON'S EPITAPH

ON PHILLIPS, THE WELSH VIOLINIST. Johnson and Garrick

were sitting together, when among other things Garrick repeated

an epitaph upon Phillips, by a Dr. Wilkes, which was very commonplace,

and Johnson said to Garrick, "I think, Davy, I can make a better."

Then, stirring about his tea for a little while in a state of meditation,

he, almost extempore, produced the following verses:—

Boswell says, "Mr.

Garrick appears not to have recited the verses correctly, the original

being as follows. One of the various readings is remarkable, and

it is the germ of Johnson's concluding line:—

Boswell's "Journal

of a Tour to the Hebrides" contains the author's letter to

Garrick asking him to send the "bad verses which led Johnson

to make his fine verses on Phillips the musician." Garrick

replied, enclosing the desired epitaph. Boswell remarks,

"This epitaph is so exquisitely beautiful that I remember even

Lord Kames, strangely prejudiced as he was against Dr. Johnson,

was compelled to allow it very high praise. It has been ascribed

to Garrick, from its appearing at first with the signature G.; but

I heard Mr. Garrick declare that it was written by Dr. Johnson." The epitaph of Phillips

is in the porch of Wolverhampton Church. The prose part of it is

curious:— Near this place lies

DR. JOHNSON'S KNOWLEDGE

OF MUSIC. He said he knew "a

drum from a trumpet, and a bagpipe from a guitar, which was about

the extent of his knowledge of music." He further tells us

that "if he had learnt music he should have been afraid he

should have done nothing else but play. It was a method of employing

the mind, without the labour of thinking at all, and with some applause

from a man's self." These remarks are better appraised and

understood when we bear in mind Dr. Johnson's own estimate of his

musical knowledge together with his having derived pleasure from

listening to the sounds of the bagpipes. If a performance on those

droning instruments was in the Doctor's mind when he said that the

reflective powers need not be exercied in performing on a musical

instrument, there might be some truth in the observation. The labour

of thinking, however, cannot be dispensed with in connection with

playing most musical instruments, and least of all the Violin. DR. JOHNSON ON FIDDLING

AND FREE WILL. "Johnson:

'Moral evil is occasioned by free will, which implies choice between

good and evil. With all the evil that there is, there is no man

but would rather be a free agent, than a mere machine without the

evil; and what is best for each individual must be best for the

whole. If a man would rather be the machine, I cannot argue with

him. He is a different being from me.' "Boswell:

'A man, as a machine, may have agreeable sensations; for instance,

he may have pleasure in music.' "Johnson:

'No, sir, he cannot have pleasure in music; at least no power of

producing music; for he who can produce music may let it alone;

he who can play upon a Fiddle may break it: such a man is not a

machine.'"—"Tour to the Hebrides." HAYDN IN LONDON.—A "SWEET

STRADIVARI." The following extracts,

taken from "A Country Clergyman of the Eighteenth Century,"

a pleasant and entertaining book (consisting of selections from

the correspondence of the Rev. Thomas Twining, M.A.), cannot fail

to interest the reader. The Rev. Thomas Twining was born in 1735.

He was an excellent musician, both in theory and practice, and a

lover of the Violin. He had collected much valuable information

with regard to music, with a view to writing a history of the subject.

Upon learning that Dr. Burney was engaged on his History of Music,

he not only generously placed his valuable notes at the service

of the Doctor, but revised the manuscript of his friend's History.

Dr. Burney, in the preface of his work, says: "In order to

satisfy the sentiments of friendship, as well as those of gratitude,

I must publicly acknowledge my obligations to the zeal, intelligence,

taste, and erudition of the Rev. Mr. Twining, a gentleman whose

least merit is being perfectly acquainted with every branch of theoretical

and practical music." The publication of

the volume containing the interesting correspondence between Dr.

Burney and his friend not only serves to enlighten us relative to

the substantial aid given to our musical historian, but also makes

us acquainted with an English eighteenth century amateur and votary

of the Fiddle of singular ability and rare humility:— "COLCHESTER, February 15,

1791. "To DR. BURNEY,— "... And now,

my dear friend, let's draw our stools together, and have some fun.

Is it possible we can help talking of Haydn first? How do you like

him? What does he say? What does he do? What does he play upon?

How does he play?... The papers say he has been bowed to by whole

orchestras when he has appeared at the play-houses. Is he about

anything in the way of composition? Come, come! I'll pester you

no more with interrogations; but trust to your generosity to gratify

my ardent curiosity in your own way. I have just—and I am

ashamed to say but just—sent for his 'Stabat Mater.' Fisin

told me some quartetts had, not long ago, been published by him.

He has written so much that I cannot help fearing he will soon have

written himself dry. If the resources of any human composer could

be inexhaustible, I should suppose Haydn's would; but as, after

all, he is but mortal, I am afraid he must soon get to the bottom

of his genius-box. My friend Mr. Tindal is come to settle (for the

present at least) in this neighbourhood. He is going to succeed

me in the curacy of Fordham. He plays the Fiddle well, the Harpsichord

well, the Violoncello well. Now, sir, when I say 'well,' I can't

be supposed to mean the wellness that one should predicate of a

professor who makes the instrument his study; but that he plays

in a very ungentlemanlike manner, exactly in time and tune, with

taste, accent, and meaning, and the true sense of what he plays;

and, upon the Violoncello, he has execution sufficient to play Boccherini's

quintettos, at least what may be called very decently. But ask Fisin,

he will tell you about our Fiddling, and vouch for our decency at

least. I saw in one of the public prints an insinuation that Haydn,

upon his arrival in London, had detected some forgeries, some things

published in his name that were not done by him. Is that true? It

does not seem very unlikely." ·

·

·

·

· Haydn left Vienna

December 15, 1790, and arrived with Salomon in London on New Year's

Day, 1791. The Rev. Thomas Twining's interrogations addressed to

Dr. Burney respecting him were therefore made but a few weeks after

Haydn's first arrival in England. Between the months of January

and May much had been seen and heard of Haydn, information of which

Dr. Burney gave to his friend, as seen in the following letter:— "COLCHESTER, May 4,

1791. "To DR. BURNEY,— "How good it

was of you to gratify me with another canto of the 'Haydniad'! It

is all most interesting to me. I don't know anything—any musical

thing—that would delight me so much as to meet him in a snug

quartett party, and hear his manner of playing his own music. If

you can bring about such a thing while I am in town, either at Chelsea,

or at Mr. Burney's, or at Mr. Salomon's, or I care not where—if

it were even in the Black Hole at Calcutta (if it is a good hole

for music)—I say, if by hook or crook you could manage such

a thing, you should be my Magnus Apollo for the rest of your life.

I mention Salomon because we are a little acquainted. He has twice

asked me to call upon him, and I certainly will do it when I come

to town. I want to hear more of his playing; and I seem, from the

little I have seen of him, to like the man. I know not how it is,

but I really receive more musical pleasure from such private cameranious Fiddlings

and singings, and keyed instrument playings, than from all the apprêtof

public and crowded performances. "I have lately

had a sort of Fiddle mania upon me, brought on by trying and comparing

different Stainers and Cremonas, &c. I believe I have got possession

of a sweet Stradivari, which I play upon with much more pleasure

than my Stainer, partly because the tone is sweeter, mellower, rounder,

and partly because the stop is longer. My Stainer is undersized,

and on that account less valuable, though the tone is as bright,

piercing, and full, as of any Stainer I ever heard. Yet, when I

take it up after the Stradivari it sets my teeth on edge. The tone

comes out plump, all at once. There is a comfortable reserve of

tone in the Stradivari, and it bears pressure; and you may draw

upon it for almost as much tone as you please. I think I shall bring

it to town with me, and then you shall hear it. 'Tis a battered,

shattered, cracky, resinous old blackguard; but if every bow that

ever crossed its strings from its birth had been sugared instead

of resined, more sweetness could not come out of its belly. Addio,

and ever pardon my sins of infirmity. "Yours truly,

GAINSBOROUGH AS A

MUSICIAN. William Jackson,

organist of Exeter Cathedral, was intimate with Gainsborough, and

besides being a thorough musician, painted with ability. He was

also the author of many essays. In one of these he makes us acquainted

with the character of Gainsborough's musical abilities. He says,

"In the early part of my life I became acquainted with Thomas

Gainsborough, the painter, and as his character was perhaps better

known to me than to any other person, I will endeavour to divest

myself of every partiality, and speak of him as he really was. Gainsborough's

profession was painting, and music was his amusement—yet,

there were times when music seemed to be his employment, and painting

his diversion. "When I first

knew him he lived at Bath, where Giardini had been exhibiting his

then unrivalled powers on the Violin. His excellent performance

made Gainsborough enamoured of that instrument; and conceiving,

like the servant-maid in the Spectator, that the music

lay in the Fiddle, he was frantic until he possessed the very instrument

which had given him so much pleasure—but seemed much surprised

that the music of it remained behind with Giardini. He had scarcely

recovered this shock (for it was a great one to him)

when he heard Abel on the Viol da Gamba. The Violin was hung on

the willow; Abel's Viol da Gamba was purchased, and the house resounded

with melodious thirds and fifths from 'morn to dewy eve!' Many an

Adagio and many a Minuet were begun, but none completed; this was

wonderful, as it was Abel's own instrument, and,

therefore, ought to have produced Abel's own music! "Fortunately

my friend's passion had now a fresh object—Fischer's Hautboy—but

I do not recollect that he deprived Fischer of his instrument; and

though he procured a Hautboy, I never heard him make the least attempt

on it. The next time I saw Gainsborough it was in the character

of King David. He had heard a Harper at Bath—the performer

was soon Harpless—and now Fischer, Abel, and Giardini were

all forgotten—there was nothing like chords and arpeggios!

He really stuck to the Harp long enough to play several airs with

variations, and would nearly have exhausted all the pieces usually

performed on an instrument incapable of modulation (this was not

a pedal Harp), when another visit from Abel brought him back to

the Viol da Gamba. He now saw the imperfection of sudden sounds

that instantly die away—if you wanted staccato, it was to

be had by a proper management of the bow, and you might also have

notes as long as you please. The Viol da Gamba is the only instrument,

and Abel the prince of musicians! This, and occasionally a little

flirtation with the Fiddle, continued some years; when, as ill-luck

would have it, he heard Crosdill, but by some irregularity of conduct

he neither took up nor bought the Violoncello. All his passion for

the Bass was vented in descriptions of Crosdill's tone and bowing." Gainsborough's fondness

for fresh instruments is alluded to by Philip Thicknesse, who says

that during his residence at Bath, Gainsborough offered him one

hundred guineas for a Viol da Gamba, dated 1612. His offer was declined,

but it was ultimately agreed that he should paint a full-length

portrait of Mr. Thicknesse for the Viol da Gamba. Gainsborough was

delighted with the arrangement, and said "Keep me hungry; keep

me hungry! and do not send the instrument until I have finished

the picture." The Viol da Gamba was, however, sent the next

morning, and the same day the artist stretched a canvas. He received

a sitting, finished the head, rubbed in the dead colouring, &c.,

and then it was laid aside—no more was said of it or done

to it, and he eventually returned the Viol da Gamba. Jackson tells us

that Gainsborough "disliked singing, particularly in parts.

He detested reading; but was so like Sterne in his letters, that,

if it were not for an originality that could be copied from no one,

it might be supposed that he had formed his style upon a close imitation

of that author. He had as much pleasure in looking at a Violin as

in hearing it. I have seen him for many minutes surveying, in silence,

the perfections of an instrument, from the just proportion of the

model and beauty of workmanship. His conversation was sprightly;

his favourite subjects were music and painting, which he treated

in a manner peculiarly his own. He died with this expression—'We

are all going to heaven, and Vandyke is of the party.'" GARRICK AND CERVETTO. Cervetto, the famous

Violoncello-player, occupied the post of principal Violoncello at

Drury Lane for many years. His fame as a performer was almost matched

by the celebrity of his nasal organ, the tuberosity of which often

caused the audience in the gallery to exclaim, "Play up, Nosey!"

In Dibdin's "Musical Tour," 1788, we are told that "When

Garrick returned from Italy, he prepared an address to the audience,

which he delivered previous to the play he first appeared in. When

he came upon the stage he was welcomed with three loud plaudits,

each finishing with a huzza. As soon as this unprecedented applause

had subsided, he used every art, of which he was so completely master,

to lull the tumult into a profound silence; and just as all was

hushed as death, and anxious expectation sat on every face, old

Cervetto, who was better known by the name of 'Nosey,' anticipated

the very first line of the address by—aw——a tremendous

yawn. A convulsion of laughter ensued, and it was some minutes before

the wished-for silence could be again restored. That, however, obtained,

Garrick delivered his address in that happy, irresistible manner

in which he was always sure to captivate his audience; and he retired

with applause, such as was never better given, nor ever more deserved.

But the matter did not rest here; the moment he came off the stage,

he flew like lightning to the music-room, where he encountered Cervetto,

and began to abuse him vociferously. 'Wha—why—you old

scoundrel. You must be the most——' At length poor Cervetto

said, 'Oh, Mr. Garrick! vat is the matter—vat I haf do? Oh!

vat is it?' 'The matter! Why you senseless idiot—with no more

brains than your Bass-Viol—just at the—a—very

moment I had played with the audience—tickled them like a

trout, and brought them to the most accommodating silence—so

pat to my purpose—so perfect—that it was, as one may

say, a companion for Milton's visible darkness.' 'Indeed, Mr. Garrick,

it vas no darkness.' 'Darkness! stupid fool—but how should

a man of my reading make himself understood by—a——

Answer me—was not the house very still?' 'Yes, sir, indeed—still

as a mouse.' 'Well, then, just at that very moment did you not—with

your jaws extended wide enough to swallow a sixpenny loaf—yawn?'

'Sare, Mr. Garrick—only if you please hear me von vord. It

is alvay the vay—it is, indeed, Mr. Garrick—alvay the

vay I go ven I haf the greatest rapture, Mr. Garrick.'

The little great man's anger instantly cooled. The readiness of

this Italian flattery operated exactly contrary to the last line

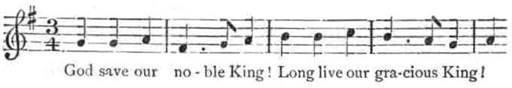

of an epigram—the honey was tasted, and the sting forgot." THE KING AND THE

PLAYER. George the Third

was frequently at Weymouth, and often strolled about the town unattended.

On the day of Elliston's benefit (at which His Majesty had expressed

his intention of being present) he had been enjoying one of his

afternoon wanderings, when a shower of rain came on. Happening to

be passing the theatre door, in he went. Finding no one about, he

entered the Royal box, and seated himself in his chair. The dim

daylight of the theatre and slight fatigue occasioned by his walk,

induced drowsiness: His Majesty, in fact, fell into a doze, which

ultimately resolved itself into a sound sleep. In the meantime Lord

Townsend met Elliston, of whom he inquired if he had seen the King,

as His Majesty had not been at the palace since his three o'clock

dinner, it being then nearly five. Elliston being unable to give

his lordship any information, Lord Townsend sought His Majesty in

another direction, and the comedian made his way to the theatre,

in order to superintend the necessary arrangements for the reception

of his Royal patrons. Upon reaching the theatre, Elliston went at

once to the King's box, and seeing a man fast asleep in His Majesty's

chair, was about recalling him to his senses somewhat roughly, when,

happily, he discovered who it was that had so unexpectedly taken

possession of the Royal chair. What was to

be done? Elliston could not presume to wake His Majesty—to

approach him—speak to him—touch him—impossible!

and yet something was necessary to be done, as it was time to light

the theatre, and, what was of still more importance, to relieve

the anxiety of the Queen and family. Elliston hit on the following

expedient: Taking up a Violin from the orchestra he stepped into

the pit, and placing himself beneath his exalted guest, struck up dolcemente—

The expedient produced

the desired effect. The sleeper was loosened from the spell which

bound him. Awakened, His Majesty stared at the comedian full in

the face, ejaculated, "Hey, hey, hey!—what, what—oh,

yes! I see—Elliston—ha, ha! Rain came on—took

a seat—took a nap. What's o'clock?" "Nearly six,

your Majesty." "Say I'm here. Stay, stay! This wig won't

do—eh, eh! Don't keep the people waiting—light up; light

up; let them in—fast asleep. Play well to-night, Elliston."

The theatre was illuminated; messengers were despatched to the Royal

party, which, having arrived in due course, Elliston quitted the

side of the affable Monarch, and prepared

himself for his part in the performance. SIR WALTER SCOTT

ON MUSIC AND FIDDLES. "I do not know

and cannot utter," said Sir Walter, "a note of music;

and complicated harmony seems to me a babble of confused, though

pleasing sounds; yet simple melodies, especially if connected with

words and ideas, have as much effect on me as on most people. I

cannot bear a voice that has no more life in it than a pianoforte

or bugle-horn. There is in almost all the fine arts a something

of soul and spirit, which, like the vital principle in man, defies

the research of the most critical anatomist. You feel where it is

not, yet you cannot describe what it is you want." Sir Joshua,

or some other great painter, was looking at a picture on which much

pains had been bestowed. "Why—yes," he said, in

a hesitating manner; "it is very clever—very well done.

Can't find fault, but it wants something—it wants—it

wants—d—n me, it wants that!" throwing his hand

over his head, and snapping his fingers. In talking of his ignorance

of music, Scott said he had once been employed in a case where a

purchaser of a Fiddle had been imposed on as to its value. He found

it necessary to prepare himself by reading all about Fiddles in

the encyclopædias,& c., and having got the names of Stradivari,

Amati, &c., glibly on his tongue, got swimmingly through his

case. Not long after this, dining at the Duke of Hamilton's, he

found himself left alone after dinner with the Duke, who had but

two subjects he could talk of—hunting and music. Having exhausted

hunting, Scott thought he would bring forward his lately acquired

learning in Fiddles, upon which the Duke grew quite animated, and

immediately whispered some orders to the butler, in consequence

of which there soon entered the room about half-a-dozen tall servants,

all in red, each bearing a Fiddle case, and Scott found his knowledge

brought to no less a test than that of telling by the tones of each

Fiddle, as the Duke played it, by what artist it was made. "By

guessing and management," said he, "I got on pretty well,

till we were, to my great relief, summoned to coffee." I have frequently

heard of the Duke's passion for Violins, and also that he had a

great number of them at Hamilton Palace. Among these instruments

there appears to have been a singularly perfect Tenor by the brothers

Amati. Signor Piatti has often spoken to me of having seen this

instrument several years since in the possession of the family.

The Hamilton collection of Fiddles was doubtless dispersed long

before the rare MSS., the Beckford Library, the inlaid cabinets,

and other treasures which served to make Hamilton Palace renowned

throughout the world of art and letters. Returning to the

subject of Sir Walter Scott's references to music, it will be seen

that his barristers possess among their gentlemanly embellishments

a knowledge of stringed instruments. Who can forget that the young

Templar, Master Lowestoffe ("Fortunes of Nigel," chap.

xvi. 138) "performed sundry tunes on the Fiddle and French

Horn" in Alsatia; and that Counsellor Pleydell, on the eventful

night, in "Guy Mannering" (chap. xlix. 255), being a "member

of the gentlemen's concert in Edinburgh," was performing some

of Scarlatti's sonatas with great brilliancy upon the Violoncello

to Julia's accompaniment upon the harpsichord? A CINDERELLA VIOLONCELLO. A somewhat curious

change in the ownership of a Violoncello occurred many years since.

My father (Mr. John Hart) was walking along Oxford Street, when

he heard the sounds of a Violoncello, a Violin, and a Cornet, which

were being played in a side street. His curiosity being excited,

he became one of the group of listeners. The appearance of the Violoncello

greatly pleased him; it was covered with a thick coat of resin and

dirt, but its author was clearly defined nevertheless. When the

players had concluded their performance, Mr. Hart asked the wandering

Violoncellist if he was disposed to sell his instrument. "I

have no objection, if I can get enough to buy another and something

over," was the answer. The terms not being insurmountable,

a bargain was struck, and the dealer in Fiddles walked away, taking

his newly-acquired purchase under his arm. The itinerant trio, having

become a duet, gave up work for that day. Reaching home with

his charge, Mr. Hart was in the act of removing the accumulated

dirt of many a hard day's work from the Violoncello, when Robert

Lindley entered, and asked what might be the parentage of the instrument

about which so much pains were being taken. "A Forster,"

was the reply; and at the same time the circumstances of the purchase

were related. Lindley was much amused, and expressed a wish to possess

the rescued instrument, though it had been much injured. The price

was agreed upon, and the Violoncello thus passed from the most humble

to the most exalted player in one day. A STOLEN "STRAD." It has often been

remarked that to steal a valuable Violin is as hazardous as to steal

a child; its identity is equally impregnable, in fact, cannot be

disguised, save at the price of entire demolition. To use a paradox,

Violins, like people, are all alike, yet none are alike. The indelible

personality of the best Violins has been a powerful agent in the

cause of morality, and has deterred many from attempting to steal

them. We have, however, instances of undiscovered robberies of valuable

instruments, and notably that of the fine Stradivari which belonged

to a well-known amateur, an attaché at the British Embassy at St.

Petersburg. The Violin in question was numbered with the Plowden

collection. I disposed of it to the amateur above mentioned in 1868;

it was a magnificent Violin, date 1709, in the highest state of

preservation. In the year 1869 the owner of it was appointed to

the Embassy at St. Petersburg, and removed thither. He was a passionate

lover of the Violin, and an excellent player. One evening he was

playing at a musical party. After he had finished he placed his

"Strad" in its case as usual, which he closed, without

locking it. The next day he was amusing himself with a parrot, which

bit him on the lip; the wound appeared very unimportant, but exposure

to the cold brought on malignant abscess, and he sank and died.

In due course his representatives arrived in St. Petersburg, and

took charge of his property, which was brought to England. Some

twelve months afterwards a relative (Mr. Andrew Fountaine, of Narford),

who took much interest in valuable Violins, was visiting the family

of the deceased gentleman and asked to be allowed to see the Stradivari,

1709. The case was sent for and duly opened. When the Violin was

handed to the visitor he remarked there must be some mistake, and

suggested that the wrong case had been brought, the instrument he

held having no resemblance whatever to the Stradivari, and not being

worth a sovereign. Inquiries were set on foot, and it was satisfactorily

proved that the case had never been opened since it had been brought

to England; neither had it left the custody of the late owner's

nearest relative, who had kept it secured in a chest. The next day

after the occurrence of the event related above, I was communicated

with, and asked if I could recognise the Stradivari in question.

It is unnecessary to record my answer. I might, with an equivalent

amount of reason, have been asked if I should know my own child.

The double case was formally opened, and the Violin described above

was taken out. "Is that the Stradivari?" I scarcely knew

for the moment whether my interrogator was in earnest, so ridiculous

was the question. It remains only to be said that the Russian authorities

were memorialised and furnished by me with a full description of

the instrument; but to this moment its whereabouts has never been

discovered. THE MISSING SCROLL. It has often happened

that portions of valuable instruments, detached from the original

whole, have been once more recovered and reinstated in their proper

place. The following is an amusing instance of this. A well-known amateur,

belonging to the generation now fast passing away, was the fortunate

possessor of a Stradivari Violin, which he had occasion to take

to the Fiddle doctor for an operation quite unknown to the students

of the Royal College of Surgeons, but well understood by the members

of the fraternity to which I have the honour to belong, namely, decapitation.

This, in the Fiddle language, means the removal of the old neck,

and the splicing of a brand-new one in its place. It is an operation

wholly unattended with the horrors of human surgery. Again and again

a time was appointed for the completion of this delicate insertion,

but in vain—it was a case of hope deferred. The owner of the

Stradivari becoming wearied with this state of things, determined

to carry off his cherished instrument in its dismembered condition.

Placing the several portions in paper, he left the Fiddle doctor's

establishment, considerably annoyed and excited. Upon reaching his

home his recent ebullition of temper had entirely passed away, and

he calmly set himself to open the parcel containing his dissected

"Strad," when, to his utter dismay, he failed to find

its scroll. The anguish he suffered may be readily conceived by

the lover of Fiddles. Away he started in search of his Fiddle's

head, dead to all around him but the sense of his loss; he demanded

of every one he met whether they had by chance picked up the head

of a Fiddle. The answers were all in the negative; and many were

the looks of astonishment caused by the strange nature of the question

and the bewildered appearance of the questioner. At length he arrived

at the house of the Fiddle doctor, whose want of punctuality had

brought about the misfortune. Here was his forlorn hope! He might

possibly have forgotten to put the scroll into the parcel. His doubts

were soon at rest; the scroll had been taken with the other parts

of the instrument. Completely overcome with sorrow and vexation,

he knew not how to endeavour to recover his loss. He ultimately

decided to offer a reward of five pounds and to await the result

as contentedly as he could. A few hours after

the dejected owner of the Violin had left the shop of the Fiddle

doctor, an old woman, the keeper of an apple stall in the neighbourhood,

entered and offered for sale a Fiddle-head. The healer of Violins,

taking it into his hands, was agreeably astonished to recognise

in it the missing headpiece, and eagerly demanded of the seller

whence she had obtained it, and what might be its price. "Picked

it up in the gutter," she answered; and two shillings was the

modest value she set upon her find. Without a moment's hesitation

the money was handed to the vendor of Ribston pippins, and away

she trudged in high glee at the result of her good luck. The Fiddle

Æsculapius, equally gleeful at the course of events, resolved to

avail himself of the opportunity afforded him of gratifying a little

harmless revenge upon the fidgety amateur's haste in removing the

"Strad" before the alterations had been completed. He

therefore determined to keep the fact of the discovery to himself

for a short time. Advertisements multiplied, and the reward rapidly

rose to twenty guineas. Having satisfied his revengeful feelings,

the repairer duly made known the discovery of the missing scroll,

to the intense gratification of its owner. Finally, the repairer

refused to accept any portion of the reward upon one condition,

viz., that he was allowed to complete his work—a condition

readily conceded. ANOTHER WANDERING

SCROLL. Among the collection

of valuable Violins belonging to the late Mr. James Goding, was

a Stradivari Violin, dated 1710, which had been deprived of its

original scroll, and bore a supposititious figure-head by David

Tecchler, owing to a piece of vandalism perpetrated by an eccentric

amateur. The original scroll had found its way to an Italian Violin

of some merit, the value of which was considerably enhanced by the

newly-acquired headpiece, which gave to the whole instrument an

air of importance to which it could lay no claim till it carried

on its shoulders a head belonging to the aristocracy of Fiddles.

During a period of about twenty years this mongrel Fiddle became

the property of as many owners, and ultimately fell into my hands.

Leaving this instrument, we will follow the history of the Stradivari,

date 1710. At the dispersion of Mr. Goding's collection by Messrs.

Christie and Manson, in the year 1857, a well-known amateur purchased

the Violin for the sum of seventy pounds, the loss of its scroll

preventing the realisation of a higher figure. Sixteen years after

this event the purchaser applied to me for a Stradivari scroll,

that he might make his instrument complete. The mongrel Violin described

above being in my possession, decapitation was duly performed, and

the Stradivari received its head again. Here was a fortuitous course

of circumstances! This exchange of heads took place without my being

at all aware that the "Strad" scroll had returned to its

original body; but on my mentioning the circumstance to my father,

he informed me, to my astonishment and delight, that if the head

of the mongrel Fiddle had been placed on the Stradivari, date 1710,

from the Goding collection, it was now, as the effect of recent

transmigration, on its own legitimate body. A MONTAGNANA INSTRUMENT

SHOT THROUGH THE BODY IN THE REVOLUTION OF 1848. An enthusiastic amateur

was playing the Violin in a house in one of the leading thoroughfares

in Paris at the outbreak of the Revolution in 1848. His ardour was

so great that the cannonading failed to interrupt him in his pleasurable

pursuit; he fiddled on, regardless of all about him, as Nero is

said to have done when his capital was in flames, and even left

the window of his apartment open. Presently a whizzing noise, terminating

in a thud above his head, arrested his attention. Upon his looking

up he saw the mark of a bullet in the ceiling. Aroused to a sense

of his danger, he closed the windows. Being about to put his Montagnana

into its case, his astonishment may be imagined when he discovered

a hole through the upper side, and a corresponding chink in the

belly, both as sharply cut as though a centre-bit had done the work.

His Violin bore witness to his miraculous escape; the bullet lodged

in the ceiling had taken his Montagnana in its course. The instrument

referred to in this anecdote has been in my possession more than

once. FIDDLE MARKS AND

THE CREDULOUS DABBLERS. It is said that a

drowning man will clutch at a straw; the truth of the remark applies

to the half-informed in Fiddle connoisseurship. It is very amusing

to note the pile of nothings that these persons heap up under the

name of "guiding points" in relation to Fiddles. I will

endeavour to call to mind a few of these. I will begin with those

little pegs seen on the backs of Violins near the button, and at

the bottom; the position of these airy nothings without habitation

or name "is deemed indisputable evidence of certain makers'

handicraft." One is supposed to have put his pegs to the right,

another to the left; another used three, four, and so on. I have

frequently heard this remark—"Oh, it cannot be a Stradivari,

because the pegs are wrong!" The purfling also

forms an important item in the collection of landmarks; certain

makers are supposed to have invariably used one kind of purfling,

no variation being allowed for width or material adopted. Original

instruments are pronounced spurious and spurious original by this

test. All Fiddles purfled with whalebone are dubbed "Jacobs,"

and no other maker is credited with using such purfling. The back of a Violin

is another very important item with these individuals. Particular

makers are supposed to have only made whole backs, others double

backs; others again are thought to be known only by the markings

of the wood. There is another crotchet to be mentioned: some will

tell you they will inform you who made your Violin by taking the

belly off, and examining the shape of the blocks and linings. Rest

assured if the maker cannot be seen outside, he will never reveal

himself in the inner consciousness of a Fiddle.

Measurement is another certain guiding point with these dabblers;

the measuring tape is produced and the instrument condemned if it

does not tally with their erroneous theory. "GUARNERI"

AT A DISCOUNT. With what tenacity

do persons often cling to the fond belief that undoubted Raffaeles,

Cinque Cento bronzes, dainty bits of Josiah Wedgwood's ware, and

old Cremonas, are exposed for sale in the windows of dealers in

unredeemed pledges, brokers' shops, and divers other emporiums!

It is the firm conviction of these amiable persons that scores of

gems unknown are awaiting in such cosy lurking-places the recognition

of the educated eye for their immediate deliverance to the light

of day. The quasi bric-à-brac

portion of the general dealer's stock is dexterously arrayed in

his window, and not allowed to take up a prominent position among

the wares displayed. To expose treasures would be a glaring act

of indiscretion, inasmuch as it would tend to the belief that the

proprietor was perfectly cognisant of the value of his goods, whereas

he is imagined by the hypothesis to be profoundly ignorant on the

subject. Pictures, bronzes, china, and Fiddles, with their extremely

modest prices attached, lie half hidden behind a mountain of goods

of a diametrically opposite nature. There they may rest for days,

nay, weeks, before the individual with the educated eye, for the

good of all men, detects them. Sooner or later, however, he makes

his appearance, and peers into every nook of the window, shading

his eyes with his hands. Something within arrests his attention;

his nose gets flattened against the glass in his eagerness to get

near the object. He enters the establishment, and asks to be allowed

to look at an article quite different from the one he has been so

intent upon; his object being that the dealer may not awaken to

a sense of the coveted article's value by a stranger seeming to

be interested in it. After examining the decoy bird, he returns

it, and carelessly asks to look at the article.

Whatever the value set upon it may be, he tenders exactly the half,

the matter being usually settled by what is technically known as

"splitting the difference." Delighted with his purchase,

he carries it home, and persuades his friends he has got to the

blind side of the dealer, and is in possession of the real thing

for the fiftieth part of what others give for it. He proceeds to

enlighten his friends on the subject, telling them to follow his

example, which they invariably do. Scarcely a day passes

without my hearing of a Cremona having been secured in the manner

I have attempted to describe. My experience, however, teaches me

that the whole thing is a delusion, and that the thoroughbred Cremona

does not fall away from the companionship of its equals, once in

the space of a lifetime, and that when this does happen, the instrument

rarely falls to the bargain-hunter. The following exceptional

incident will, I hope, not be found wanting in interest as bearing

on this theme. A votary of the Violin purchased an old Fiddle for

some two or three pounds from a general dealer in musical instruments

in his neighbourhood. He was well satisfied with his acquisition;

and after subjecting it to a course of judicious regulation, so

great were the improvements effected that the vendor regretted having

sold it for such a trifling sum, and the more so when it was whispered

about that the instrument was a veritable Amati—a report,

by the way, very far wide of the mark, as it was simply an old Tyrolean

copy. Some little time

after the occurrence related, the lover of Violins heard that the

same instrument-seller from whom he purchased the imagined Amati,

had secured a job lot of some half-dozen old Fiddles, the remnant

of an old London music-seller's stock, and that he was offering

them for sale. Our hero decided to pay another visit, and judge

of the merits of the new wares, with a view to a second investment.

Upon presenting himself to the local seller of Violins, he was at

once informed that if he selected any instrument

from the lot, he must be prepared to pay £10, the dealer having

no intention of again committing his former error in selling a Cremona

for some forty shillings. Upon this understanding the visitor proceeded

to examine the little stock, which he found in a very disordered

condition—bridgeless, stringless, and dusty. Among the whole

tribe, however, was a Violin which seemed to elbow its way to the

front of the group, and clamour for the attention of which it appeared

to deem itself worthy. Unable to resist its seeming appeal, the

intending purchaser decided to remove it from the atmosphere of

its companions, and begged that he might be permitted to take the

importuning Fiddle and string it in order to test its qualities.

His request being acceded to, he carried it away. Upon reaching

home, he took it from its case, and gently removed the dust of years.

The varnish appeared to him as something very different from any

he had ever seen before on a Violin; and being an artist by profession,

qualities of colours were pretty well understood by him. With the

Violin poised on his knee, somewhat after the manner seen in the

well-known picture of Stradivari in his workshop, he thus communed

with himself: "I have never seen the much-spoken-of Cremonese

varnish, but if this instrument has it not, its lustre must indeed

be more wondrous than my imagination has painted." After again

and again examining the Violin, he retired to rest, but not to sleep.

The Fiddle persisted in dodging him whichever way he turned on his

couch. At the dawn of day—five o'clock—he was up, with

the Fiddle again on his knee, thinking he might have been labouring

under some infatuation the night before which the light of day might

dispel. Convinced he was under no such delusion, he soon made for

the music-seller's establishment, whom he delighted by paying the

price demanded for the Violin. It was now time, he felt, to obtain

professional advice on the matter; in due course he paid me a visit.

Upon his opening the case I was unable to restrain my feelings of

surprise, and demanded if he had any idea of the value of the Violin.

"None whatever," he answered. Without troubling the reader

further, I informed him that his Violin was an undoubted Giuseppe

Guarneri, of considerable value. He then recounted the circumstances

attending its purchase, with which the reader is familiar. DOMENICO DRAGONETTI—HIS

GASPARO DA SALÒ. Signor Dragonetti

succeeded Berini as primo basso in the orchestra

of the chapel belonging to the monastery of San Marco, Venice, in

his eighteenth year. The procurators of the monastery, wishing to

show their high appreciation of his worth, presented the youthful

player with a magnificent Contra-Bass, by Gasparo da Salò, which

had been made expressly for the chapel orchestra of the convent

of St. Peter, by the famous Brescian maker. Upon an eventful

night, the inmates of the monastery retired to rest, when they were

awakened by deep rumbling and surging sounds. Unable to find repose

while these noises rent the air, they decided to visit the chapel;

and the nearer they got to it the louder the sounds became. Regarding

each other with looks of mingled fear and curiosity, they reached

the chapel, opened the door, and there stood the innocent cause

of their fright, Domenico Dragonetti, immersed in the performance

of some gigantic passage, of a range extending from the nut to the

bridge, on his newly-acquired Gasparo. The monks stood regarding

the performer in amazement, possibly mistaking him for a second

appearance of the original of Tartini's "Sonata del Diavolo,"

his Satanic Majesty having substituted the Contra-Basso for the

Violin. Upon this instrument Dragonetti played at his chief concert

engagements, and though frequently importuned to sell it by his

numerous admirers, declined to do so; in fact, though for the last

few years of his life he gave up public performance, he resolutely

refused most tempting offers for his treasure—£800, to use

an auctioneer's phrase, "having been offered in two places,"

and respectfully declined. In his youthful days he decided that

his cherished Gasparo should return to the place from whence he

obtained it, the Monastery of San Marco, and this wish was accordingly

fulfilled by his executors in the year 1846. The occasion was one

of much interest; it was felt by Dragonetti's friends and admirers

that to consign the instrument upon which he had so often astonished

and delighted them with the magic tones he drew from it, to the

care of those who possibly knew nothing of its merits, was matter

for regret. Being desirous of

furnishing the reader with all the information possible relative

to Signor Dragonetti's instrument I communicated with Mr. Samuel

Appleby, who was his legal adviser, and probably better acquainted

with him than any other person in this country. He very kindly sent

me the following particulars, which are interesting:— "BRIGHTON, July 2,

1875. "MY DEAR SIR,— "Your letter

of yesterday needs no apology, as it will afford me pleasure at

any time to give you any information in my power respecting the

late Signor Dragonetti, having known him well from 1796 to his death. "His celebrated

Gasparo da Salò instrument, or Contra-Basso, was left by his will

to the Fabbricieri (or churchwardens) for the time being of the

Church of St. Mark's, at Venice, to be played upon only on festivals

and grand occasions. I was present on one of such festivals, which

lasted three days, in July, 1852. I then saw the Basso, which was

played on in Orchestra No. 1, there having been two bands for which

music had been composed expressly. "In April, 1875,

being again in Venice, I inquired from the Verger of St. Mark's

if Dragonetti's Violone was in the church, and

I could see it. The reply was in the affirmative, but as the Fabbricieri

had the care of the instrument, under lock and key, it would be

necessary to see them and get their consent for its production.

As this would cause me some little trouble, I left Venice without

carrying out my intention. "Dragonetti

by his will left me his Amati Double-Bass, which is now in this

house, and I believe the only one of that make in England, and consequently

highly prized by "Yours truly,

"Mr. Hart." THE BETTS STRADIVARI. The Bibliophile tells

us of Caxton, Aldine, and Baskerville editions having been exposed

for sale by itinerant booksellers, men who in opening their umbrellas

opened their shops. Collectors of pictures, china, and Fiddles,

have each their wondrous tales to tell of bygone bargains, which

are but the echoes of that of the Bibliophile. It is doubtful, however,

were we to search throughout the curiosities of art sales, whether

we should discover such a bargain as Mr. Betts secured, when he

purchased the magnificent Stradivari which bears his name, for twenty

shillings. About half a century since, this instrument was taken

to the shop of Messrs. Betts, the well-known English Violin-makers

in the old Royal Exchange, and disposed of for the trivial sum above-mentioned.

Doubtless its owner believed he was selling a brand-new copy, instead

of a "Stradivari" made in 1704, in a state of perfection.

Frequently importuned to sell the instrument, Mr. Betts persistently

declined, though it is recorded in Sandys and Foster's work on the

Violin, that five hundred guineas were tendered more than once,

which in those days must have been a tempting offer indeed! Under

the will of Mr. Betts it passed to his family, who for years retained

possession of it. About the year 1858

it became the property of M. Vuillaume, of Paris, from whom it was

purchased by M. Wilmotte, of Antwerp. Several years later it passed

to Mr. C. G. Meier, who had waited patiently for years to become

its owner. The loving care which this admirer of Cremonese Violins

bestowed upon it was such, that he would scarcely permit any person

to handle it. From Mr. Meier it passed into my possession in the

year 1878, which change of ownership brought forth the following

interesting particulars from the pen of the late Charles Reade,

the novelist and lover of Fiddles:— "THE BETTS STRADIVARI. "To the Editor

of the 'Globe.' "SIR,—As

you have devoted a paragraph to this Violin, which it well deserves,

permit me to add a fact which may be interesting to amateurs, and

to Mr. George Hart, the late purchaser. M. Vuillaume, who could

not speak English, was always assisted in his London purchases by

the late John Lott, an excellent workman, and a good judge of old

Violins.The day after this particular purchase, Lott came to Vuillaume,

by order, to open the Violin. He did so in the sitting-room whilst

Vuillaume was dressing. Lott's first words were, 'Why, it has never

been opened!' His next, 'Here's the original bass-bar.' Thereupon

out went M. Vuillaume, half-dressed, and the pair gloated over a

rare sight, a Stradivari Violin, the interior of which was intact

from the maker's hands. Mr. Lott described the bass-bar to me. It

was very low and very short, and quite unequal to support the tension

of the strings at our concert pitch, so that the true tone of this

Violin can never have been heard in England before it fell into

Vuillaume's hands. I have known this Violin forty years. It is wonderfully

preserved. There is no wear on the belly except the chin-mark; in

the centre of the back a very little, just enough to give light

and shade. The corners appear long for the epoch, but only because

they have not been worn down. As far as the work goes, you may know

from this instrument how a brand-new Stradivari Violin looked. Eight

hundred guineas seems a long price for a dealer to give: but after

all, here is a Violin, a picture, and a miracle all in one; and

big diamonds increase in number; but these spoils of time are limited

for ever now, and, indeed, can only decrease by shipwreck, accident,

and the tooth of time.—I am, your obedient servant, "CHARLES READE. "19, ALBERT

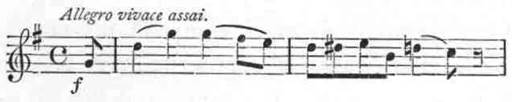

GATE, May 9, 1878." LEIGH HUNT ON PAGANINI. "'I projected,'

says Leigh Hunt, 'a poem to be called "A Day with the Reader."

I proposed to invite the reader to breakfast, dine and sup with

me, partly at home, and partly at a country inn, to vary the circumstances.

It was to be written both gravely and gaily; in an exalted, or in

a lowly strain, according to the topics of which it treated. The

fragment on Paganini was a part of the exordium:—

I wished to write

in the same manner, because Paganini with his Violin could move

both the tears and the laughter of his audience, and (as I have

described him doing in the verses) would now give you the notes

of birds in trees, and even hens feeding in a farmyard (which was

a corner into which I meant to take my companion), and now melt

you into grief and pity, or mystify you with witchcraft, or put

you into a state of lofty triumph like a conqueror. The phrase of smiting the chord—

was no classical

commonplace; nor, in respect to impression on the mind, was it exaggeration

to say, that from a single chord he would fetch out—

Paganini, the first

time I saw and heard him, and the first time he struck a note, seemed

literally to strike it—to give it a blow.

The house was so crammed, that being among the squeezers in the

standing-room at the side of the pit, I happened to catch the first

glance of his face through the arm a-kimbo of a man who was perched

up before me, which made a kind of frame for it; and there on the

stage, in that frame, as through a perspective glass, were the face,

bust, and the raised hand of the wonderful musician, with the instrument

at his chin, just going to commence, and looking exactly as I have

described him.

"'To show the

depth and identicalness of the impression which he made upon everybody,

foreign or native, an Italian who stood near me said to himself,

after a sigh, "O Dio!" and this had not been said long

when another person, in the same manner, uttered "O Christ!"

Musicians pressed forward from behind the scenes to get as close

to him as possible; and they could not sleep at night for thinking

of him.'"—Timbs's Anecdote Biography. THACKERAY ON ORCHESTRAL

MUSIC. "I wish I were

a poet; you should have a description of all this in verse, and

welcome. But if I were a musician! Let us see what we should do

as musicians. First, you should hear the distant sound of a bugle,

which sound should float away; that is one of the heralds of the

morning, flying southward. Then another should issue from the eastern

gates; and now the grand réveilleshould grow, sweep

past your ears (like the wind aforesaid), go on, dying as it goes.

When, as it dies, my stringed instruments come in. These to the

left of the orchestra break into a soft slow movement, the music

swaying drowsily from side to side, as it were, with a noise like

the rustling of boughs. It must not be much of a noise, however,

for my stringed instruments to the right have begun the very song

of the morning. The bows tremble upon the strings, like the limbs

of a dancer, who, a-tiptoe, prepares to bound into her ecstasy of

motion. Away! The song soars into the air as if it had the wings

of a kite. Here swooping, there swooping, wheeling upward, falling

suddenly, checked, poised for a moment on quivering wings, and again

away. It is waltz-time, and you hear the Hours dancing to it. Then

the horns. Their melody overflows into the air richly, like honey

of Hybla; it wafts down in lazy gusts, like the scent of the thyme

from that hill. So my stringed instruments to the left cease rustling;

listen a little while; catch the music of those others, and follow

it. Now for the rising of the lark! Henceforward it is a chorus,

and he is the leader thereof. Heaven and earth agree to follow him.

I have a part for the brooks—their notes drop, drop, drop,

like his: for the woods—they sob like him. At length, nothing

remains but to blow the Hautboys; and just as the chorus arrives

at its fulness, they come maundering in. They have a sweet old blundering

'cow song' to themselves—a silly thing, made of the echoes

of all pastoral sounds. There's a warbling waggoner in it, and his

team jingling their bells. There's a shepherd driving his flock

from the fold, bleating; and the lowing of cattle. Down falls the

lark like a stone; it is time he looked for grubs. Then the Hautboys

go out, gradually; for the waggoner is far on his road to market;

sheep cease to bleat and cattle to low, one by one; they are on

their grazing ground, and the business of the day is begun. Last

of all, the heavenly music sweeps away to waken more westering lands,

over the Atlantic and its whitening sails."—"An

Essay without End." ADDISON ON THE PERSONIFICATION

OF THE LEADING INSTRUMENT. In the pages of the Tatler (April,

1710), Addison with much ingenuity and humour personifies certain

musical instruments. He says: "I have often imagined to myself

that different talents in discourse might be shadowed out after

the same manner by different kinds of music; and that the several

conversable parts of mankind in this great city might be cast into

proper characters and divisions, as they resemble several instruments

that are in use among the masters of harmony. Of these, therefore,

in their order; and first of the Drum. "Your Drums

are the blusterers in conversation, that with a loud laugh, unnatural

mirth, and a torrent of noise, domineer in public assemblies; overbear

men of sense; stun their companions; and fill the place they are

in with a rattling sound, that hath seldom any wit, humour, or good

breeding in it. I need not observe that the emptiness of the Drum

very much contributes to its noise. "The Lute is

a character directly opposite to the Drum, that sounds very finely

by itself. A Lute is seldom heard in a company of more than five,

whereas a Drum will show itself to advantage in an assembly of five

hundred. The Lutenists, therefore, are men of a fine genius, uncommon

reflection, great affability, and esteemed chiefly by persons of

a good taste, who are the only proper judges of so delightful and

soft a melody. "Violins are

the lively, forward, importunate wits, that distinguish themselves

by the flourishes of imagination, sharpness of repartee, glances

of satire, and bear away the upper part in every consort.

I cannot but observe, that when a man is not disposed to hear music,

there is not a more disagreeable sound in harmony than that of a

Violin. "There is another

musical instrument, which is more frequent in this nation than any

other; I mean your Bass-Viol, which grumbles in the bottom of the consort,

and with a surly masculine sound strengthens the harmony and tempers

the sweetness of the several instruments that play along with it.

The Bass-Viol is an instrument of a quite different nature to the

Trumpet, and may signify men of rough sense and unpolished parts,

who do not love to hear themselves talk, but sometimes break out

with an agreeable bluntness, unexpected wit, and surly pleasantries,

to the no small diversion of their friends and companions. In short,

I look upon every sensible, true-born Briton to be naturally a Bass-Viol." WASHINGTON IRVING

ON REALISTIC MUSIC AND THE VIOLIN. "Demi-Semiquaver

to Launcelot Langstaff, Esq. "SIR,—I

felt myself hurt and offended by Mr. Evergreen's terrible philippic

against modern music in No. 11 of your work, and was under serious

apprehension that his strictures might bring the art, which I have

the honour to profess, into contempt. So far, sir, from agreeing

with Mr. Evergreen in thinking that all modern music is but the

mere dregs and drainings of the ancient, I trust before this letter

is concluded I shall convince you and him that some of the late

professors of this enchanting art have completely distanced the

paltry efforts of the ancients; and that I, in particular, have

at length brought it almost to absolute perfection. "The Greeks,

simple souls, were astonished at the powers of Orpheus, who made

the woods and rocks dance to his lyre—of Amphion, who converted

crotchets into bricks, and quavers into mortar—and of Arion,

who won upon the compassion of the fishes. In the fervency of admiration,

their poets fabled that Apollo had lent them his lyre, and inspired

them with his own spirit of harmony. What then would they have said

had they witnessed the wonderful effects of my skill?—had

they heard me, in the compass of a single piece, describe in glowing

notes one of the most sublime operations of nature, and not only

make inanimate objects dance, but even speak; and not only speak,

but speak in strains of exquisite harmony? "I think, sir,

I may venture to say there is not a sound in the whole compass of

nature which I cannot imitate, and even improve upon;—nay,

what I consider the perfection of my art, I have discovered a method

of expressing, in the most striking manner, that indefinable, indescribable

silence which accompanies the falling of snow." [Our author describes

in detail the different movements of a grand piece, which he names

the "Breaking up of the ice in the North River," and tells

us that the "ice running against Polopay's Island with a terrible

crash," is represented by a fierce fellow travelling with his

Fiddle-stick over a huge Bass-Viol at the rate of 150 bars a minute,

and tearing the music to rags—this being what is called execution.] "Thus, sir,

you perceive what wonderful powers of expression have hitherto been