|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

SECTION VI The English School It is somewhat remarkable

that the Continental writers on the Violin should have omitted to

mention any English maker, either ancient or modern. Such an omission

must have occurred either from want of information concerning our

best makers, or, if known, they must have been deemed unworthy of

the notice of our foreign friends. There is no mention of an English

maker in the work of F�tis, "Antoine Stradivari," 1856,

although numerous very inferior German and Italian makers are quoted.

The same omission is also conspicuous in "Luthomonographie

Historique et Raisonn�," 1856, and Otto's "Ueber den Bau

der Bogeninstrumente," &c., 1828. It may be that Continental

connoisseurs have credited themselves with the works of our best

makers, and expatriated them, while they have inexorably allowed

bad English Fiddles to retain their nationality. However, it is

my desire that my foreign brothers should be enlightened on this

point, and in all candour informed of the array of makers that England has at different times

produced, and is yet capable of producing, did but the new Violin

command the price that would be a fair return for the time and skill

required in the production of an instrument at once useful and artistic.

It will be my endeavour to show forth the qualities of those of

our makers whose names, as yet, seem never to have crossed the Channel,

so that when these pages on the English School are read by distant

connoisseurs, and the merits and shortcomings of the makers therein

are fairly weighed by them, the good shall be found so to outweigh

the indifferent as to entirely change the opinions formed of us

as makers of the leading instrument.

Until the early nineteenth

century makers of Violins in England would appear to have been comparatively

numerous, if we take into consideration the undeveloped state of

stringed instrument music at that period in this country. Among

those makers were men of no ordinary genius—men who worked

lovingly, guided by motives distinct from commercial gain, so long

as they were allowed to live by their work. When, however, the duties

on foreign musical instruments were removed, the effect was to partially

swamp the gallant little band of Fiddle-makers, who were quite unable

to compete with the French and German makers in price (not excellence,

be it distinctly understood, for we were undoubtedly ahead of our

foreign competitors, both in style and finish,

at this period). The prices commanded by many English makers previous

to the repeal of the duty were thoroughly remunerative. Five to

twenty pounds were given for English Violins, while Violoncellos

and Tenors commanded prices proportionately high. The English Violin-makers

were thus enabled to bestow artistic care in the making of their

instruments. When, however, they were suddenly called upon to compete

on equal terms with a legion of foreign manufacturers, the result

was not so much that their ardour was damped, as that they themselves

were extinguished, and served as another instance of the truth of

the adage that "the good of the many is the bane of the few." In matters of magnitude,

whether artistic or otherwise, competition is undoubtedly healthy,

there being always a small body of patrons who are willing to check

the tendency to deteriorate, common to all productions, by encouraging

the worker with extra remuneration, in order that a high degree

of excellence may be maintained; but in matters confined to a small

circle, as in the case of Violin-making, the number of those willing

to encourage artistic workmanship is so minute as to fail even to

support one maker of excellence, and thus, when

deprived suddenly of its legitimate protection, the art, with other

similar handicrafts, must drift into decadence. If we look around

the Violin world, it is everywhere much the same. In Italy there

is no Stradivari in embryo, in France no coming Lupot, in Germany

no Jacob Stainer, and in England no future Banks or Forster. Why

so? The answer is twofold. Partly there is fault in the demand,

arising from the marked preference of this age for cheapness at

the expense of goodness; partly, too, there is a fault in the supply,

a foolish desire on the part of the makers to give maturity to their

instruments, wherein they always completely fail, yet they will

not give up their conceit. Here, again, were we dealing with matters

of greater magnitude, the evil influence would be lessened, the

artistic impulses would still be felt, though in a less degree;

whereas so contracted is the circle of the Violin world, that under

any stress the support given to makers willing to bestow an artist's

care on their work is totally inadequate. The case of modern

Violin-makers is unfortunate. Old Violins being immeasurably superior

to modern productions, the demand must necessarily set steadily

for the former, and the modern maker has only the few patrons of

new work to support him. It cannot be expected that the players

of to-day should patronise the modern Violin in order that the next

generation should reap the benefit. Years since it was quite a different

matter. The makers were well paid for their work, and new instruments

were then made to supply wants similar to those which the horrid

Mirecourt or Saxon copy fulfils at present. As with other things,

so is it also with Violins; if they are to be produced with the

stamp of artistic merit, they must be paid for accordingly; without

patronage the worker necessarily becomes careless. Finding that

his skill fails to attract attention, he gradually sinks down into

the mere routine of the ordinary workman. When Italy shone brightest

in art, the patronage and remuneration which the workers received

was considerable. Had it been otherwise, the powers of its Raffaele,

its Cellini, and last (though not least to the admirers of the Violin),

its Stradivari, would have remained simply dormant. Art, like commerce,

is regulated in a great measure by supply and demand. In Raffaele's

day, sacred subjects were in demand; the Church was his great patron,

and aided him in bringing forth the gift which nature had implanted

within him. In modern times, landscape-painting became the favoured

subject, particularly in England; the result of which preference

has been to place us in the foremost rank in that branch of art.

The stage furnishes another instance of the effect that patronage

has in bringing forth latent talent. If the history of dramatic

art be traced, it will be found that its chief works were written

when the taste of an appreciative public could be securely counted

upon. As it waned, so the writers of merit became rarer; or perhaps

it would be more correct to say, the plays produced became less

meritorious, the authors being constrained to pander to the prevailing

tastes. As further evidence

of the effect of patronage on art, a case in point is found in the

manufacture of Venetian glass. The Venetians, centuries ago, became

famous for their works in glass, and the patronage they enjoyed

was world-wide; but their country being thrown into an unsettled

condition, capital drifted from it, until the blowing of glass,

together with other industries, was comparatively extinguished.

Within recent years the art of making glass has shown signs, even

in Venice itself, of reviving with all its former vigour in the

workshops of Salviati, the success of which is due in great measure

to English capital. With regard to English

Violin manufacture, there would be no reason why Violins should

not, at the present moment, be produced in England which should

fully reach the standard of merit maintained in our forefathers'

days, if only the patronage of the art occupied a larger area. The

present dearth of English makers does not arise from any national

want of talent for this particular handicraft; in fact, we have

plenty of men quite as enthusiastic as our foreign friends for a

vocation which, in England also, must be pronounced to be alike

venerable in its antiquity and famed for the dexterity of its genius. The earliest makers

of Viols in England seem to have been Jay, Smith, Bolles, Ross,

Addison, and Shaw, names thoroughly British. We may take this as

good evidence that the making of Viols in England originated with

the English, and was not commenced by settlers from the Continent.

Doubtless the form of the English Viol and its brethren was taken

from the Brescian makers, there being much affinity between these

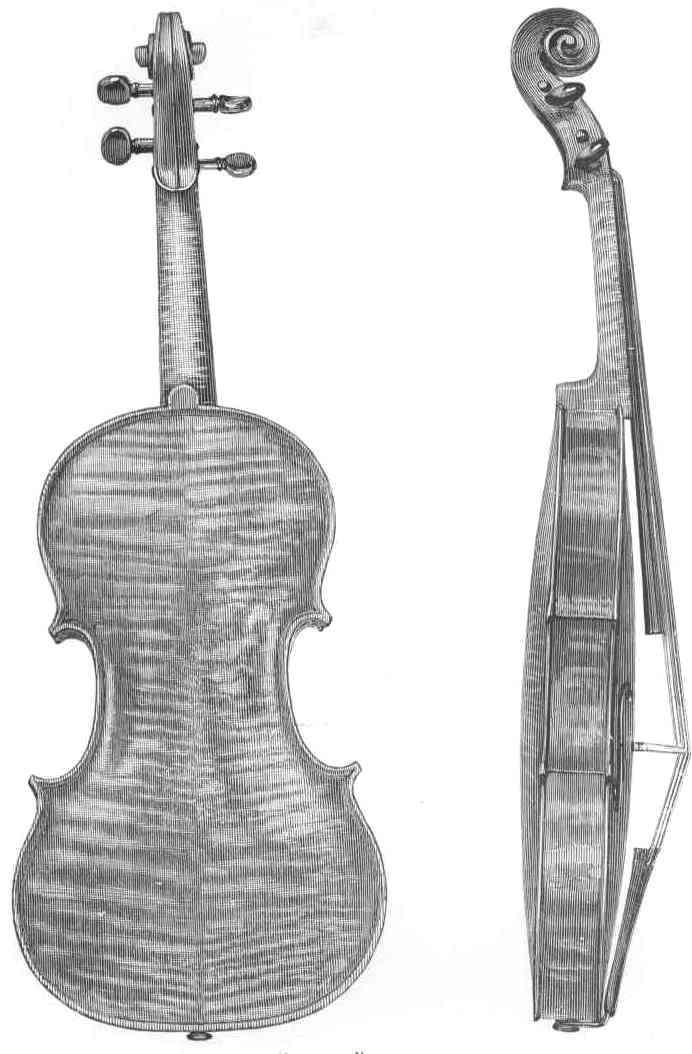

classes of instruments. In the few Violins extant by Christopher

Wise the Italian character is very striking. In them we see a flat

model, excellent outline, and varnish of good quality. The Viols

of Jay have the same Italian character. Later on we have names of

some reputation—Rayman, Urquhart, and Barak Norman. In the

absence of any direct evidence as regards the nationality of these

makers it is requisite to endeavour to trace the style belonging

to their works. It will be observed that there was a great improvement

in the style of work and varnish of instruments made in England,

commencing with the time of Rayman, and it is probable that this

step in advance was obtained from intercourse with Italy or the

German Tyrol. Starting with Rayman, there is a German ring in the

name which makes me think that he came from Germany, and, if so,

brought with him the semi-Italian character of work common to the

makers who lived so near Brescia. If the work and style of Rayman

be carefully examined, it will be seen that there is much in common

with the inferior Brescian makers. The outline is rugged, the sound-hole

is of that Gothic form peculiar to Brescia; the head is distinct

from that of the early English type. At the same period Urquhart

made instruments of great merit, the varnish of which is superior

to that of Rayman, but is evidently composed of similar ingredients.

Its superiority may have arisen from a different mode of mixing

only. The name of Urquhart has a North British sound, and it is

probable that he was born in Scotland, and settled in London as

an assistant to Rayman, who would impart to him the style of foreign

work. The semi-Italian

character pervading the instruments made in England at this period

seems to have culminated in the productions of Barak Norman, whose

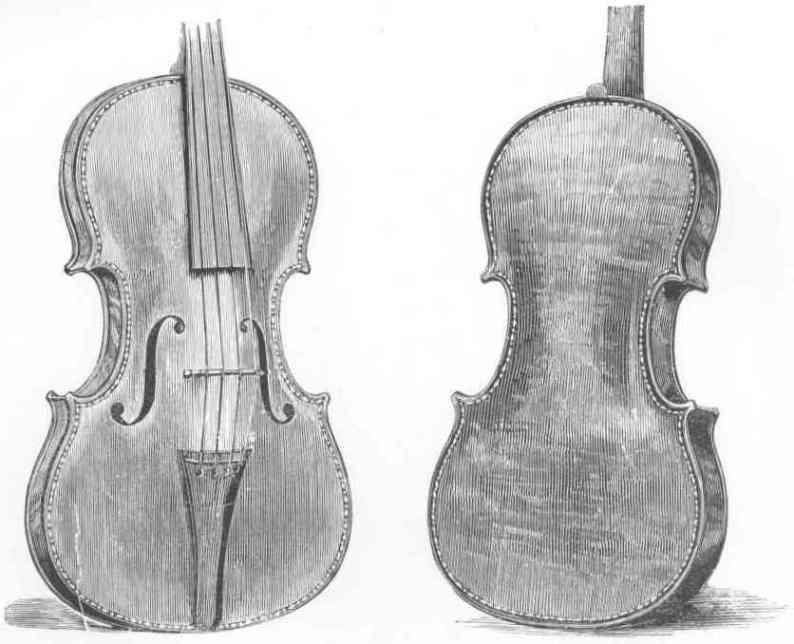

best works bear even a more marked Brescian character than those

of Rayman. The model varies very much, sometimes being high, at

other times very flat; in the latter case the results are instruments

of the Maggini type. Barak Norman frequently double-purfled his

instruments, and inserted a device in the purfling, evidently following

Maggini in these particulars. With Barak Norman ends the list of

English copyists of the Brescian makers. We now arrive at

the copyists of Jacob Stainer and the Amati, a class of makers who

possessed great abilities, and knew how to use them. The first name

to be mentioned is Benjamin Banks, of Salisbury, who may with propriety

be termed the English Amati. He was the first English

maker who recognised the superior form of Amati's model over that

of Stainer, and devoted all his energies to successful imitation.

Too much praise cannot be lavished on Banks for the example which

he selected for himself and his fellow-makers. Next follow the names

of Forster, Duke, Hill, Wamsley, Betts, Gilkes, Hart, and Kennedy,

together with those of Panormo, Fendt, and Lott, who, although not

born in England, passed the greater part of their lives here, and

therefore require to be classed with the English School. The mention

of these makers will bring the reader to the present time. Upon scanning this

goodly list, there will be found ample evidence that we in England

have had makers of sufficient merit to entitle us to rank as a distinct

school—a school of no mean order. We may therefore assume

that the Continental writers who from time to time have published

lists of makers of the Violin, and have invariably ignored England,

have erred through want of information regarding the capabilities

of our makers, both ancient and modern. The following list

will be found to enumerate nearly the whole of the English makers,

and indicate the distinctive character of their respective works. English Makers ABSAM, Thomas, Wakefield,

1833. ADAMS, Garmouth,

Scotland, 1800. ADDISON, William,

London, 1670. AIRETON, Edmund.

Was originally employed in the workshop of Peter Wamsley, at the

"Harp and Hautboy," in Piccadilly. He made a great many

excellent Violins and Violoncellos, and chiefly copied Amati. Varnish

of fair quality; colour yellow. He died at the advanced age of 80,

in the year 1807. ALDRED, ——,

about 1560. Maker of Viols. ASKEY, Samuel, London,

about 1825. BAINES, about 1780. BAKER, ——,

Oxford. Mention is made of a Viol of this maker in the catalogue

of the music and instruments of Tom Britton, the small-coal man. BALLANTINE, Edinburgh

and Glasgow, 1850. BANKS, Benjamin,

Salisbury, born 1727, died 1795. To this famous maker must be given

the foremost place in the English School. He was a thorough artist,

and would not have been thought lightly of had he worked in Cremona's

school, and been judged by its standard. This may be considered

excessive praise of our native maker; but an unprejudiced judge

of work need only turn to the best specimens of Banks's instruments,

and he will confess that I have merely recorded a fact. Banks is, again,

one of the many instances of men who have gained a lasting reputation,

but whose histories have never reached the light to which their

names have attained. How interesting would it be to obtain the name

of his master in the knowledge of making instruments! No clue whatever

remains by which we could arrive at a satisfactory conclusion on

this point. That he was an enthusiast in his art is certain, and

also that he was aware to some extent that he possessed talent of

no mean description. This is evidenced by the fact that many of

his instruments are branded with the letters B. B. in several places,

as though he felt that sooner or later his works would be highly

esteemed, and would survive base imitations, and that by carefully

branding them he might prevent any doubt as to their author. Many

of his best instruments are found to have no brand: it would seem,

therefore, that he did not so mark them for some time. He appears

to have early shown a preference for the model of Niccol� Amati,

and laboured unceasingly in imitation of him, until he copied him

with an exactness difficult to surpass. Now that time has mellowed

his best works, they might pass as original Amatis with those not

perfectly versed in the characteristics of the latter. Many German

makers excelled as copyists of Amati; but these makers chiefly failed

in their varnish, whereas Banks was most happy in this particular,

both as regards colour and quality. If his varnish be closely examined,

its purity and richness of colour are readily seen. It has all the

characteristics of fine Italian varnish, being beautifully transparent,

mellow, and rich in its varieties of tints. It must be distinctly

understood that these remarks apply only to the very finest works

of this maker, there being many specimens which bear the label of

Banks in the framing of which he probably took but a small share,

leaving the chief part to be done by his son and others. Banks cannot

be considered as having been successful in the use of his varnish

on the bellies of his instruments, as he has allowed it to clog

the fibre, a blemish which affects the appearance very much, and

has been the means of casting discredit on the varnish among those

unacquainted with the real cause. The modelling is executed with

skill. Fortunately, sufficient wood has been left in his instruments

to enable time to exert its beneficial effects, a desideratum overlooked

by many makers of good repute. The only feature of his work which

can be considered as wanting in merit is the scroll, which is somewhat

cramped, and fails to convey the meaning intended, viz., the following

of Amati; but as this is a point having reference to appearance,

and therefore solely affecting the connoisseur, it may be passed

over lightly, and the more so when we consider that Banks was not

the only clever workman who has failed in head-cutting. He made

Violins, Tenors, and Violoncellos, all excellent; but the last-named

have the preference. His large Violoncellos are the best; those

of the smaller pattern are equally well made, but lack depth of

tone. The red-varnished instruments are the favourites. BANKS, Benjamin,

son of the above, born in September, 1754; died January, 1820. Worked

many years with his father at Salisbury, afterwards removed to London,

and lived at 30, Sherrard Street, Golden Square. BANKS, James. Brother

of the above. For some years carried on the business of his father

at Salisbury, in conjunction with his brother Henry. They ultimately

sold the business and removed to Liverpool. The instruments of James

and Henry Banks are of average merit. BARNES, Robert, 1710.

Worked with Thomas Smith at the "Harp and Hautboy" in

Piccadilly. Afterwards partner with John Norris. BARRETT, John, 1714.

An average workman, who followed the model of Stainer. His shop

bore the sign of the "Harp and Crown." Barrett was one

of the earliest copyists of Stainer, and in the chain of English

makers is linked with Barak Norman and Nathaniel Cross. The wood

is generally of a very good quality, the varnish yellow. BARTON, George, Old

Bailey, London, about 1780-1810. BETTS, John, born

1755, at Stamford, Lincolnshire, died in 1823. Became a pupil of

Richard Duke. He commenced business in one of the shops of the Royal

Exchange, where he soon enjoyed considerable patronage. John Betts

does not appear to have made a great number of instruments, but

employed many workmen, into whose instruments he inserted his trade

label. He was, perhaps, the earliest London dealer in Italian instruments.

His quaintly-worded business card runs:— "John Betts,

Real Musical Instrument Maker, at the Violin and German Flute, No.

2, under the North Piazza of the Royal Exchange, makes in the neatest

manner, Violins the patterns of Antonius Stradivarius, Hi�ronymus

Amati, Jacobus Stainer, and Tyrols. Equal for the fine, full, mellow

tone to those made in Cremona. Tenors, Violoncellos, Pentachords,

&c., &c., &c." The sound-holes of

Betts' instruments are rather wide; broad purfling; scroll well

cut. BETTS, Edward, nephew

of John Betts; was a pupil of Richard Duke, whose work he copied

with considerable skill. Of course, in trying to imitate Duke he

was copying Amati, Richard Duke having spent his life in working

after the Amati pattern, without attempting to model for himself.

The care bestowed by Edward Betts on his instruments was of no ordinary

kind. The workmanship throughout is of the most delicate description;

indeed, it may be said that neatness is gained at the expense of

individuality in many of his works. Each part is faultless in finish,

but when viewed as a whole the result is too mechanical, giving

as it does the notion of its having been turned out of a mould.

Nevertheless, this maker takes rank with the foremost of the English

copyists, and in his instruments we have as good specimens of undisguised

work as can be readily found. They will be yearly more valued.

BOLLES, ——,

An early maker of Lutes and Viols. BOOTH, William, 1779

to about 1858, Leeds. BOOTH, ——,

son of the above, Leeds, died 1856. BOUCHER, ——,

London, 1764. BROWN, James, London,

born 1770, died 1834. Worked with Thomas Kennedy. BROWN, James, London,

son of the above, born 1786, died 1860. BROWNE, John, London,

about 1743. Worked at the sign of the "Black Lion," Cornhill.

Good work. Amati pattern. Scroll well cut; hard varnish. CAHUSAC, ——,

London, 1788. Associated with the sons of Banks. CARTER, John, London,

1789, worked with John Betts, and afterwards at Drury Lane on his

own account. CHALLONER, Thomas,

London. Similar to Wamsley. COLE, Thomas, London,

1690. COLE, James, Manchester,

19th century. COLLIER, Samuel,

1750. COLLIER, Thomas,

1775. COLLINGWOOD, Joseph,

London, 1760. CONWAY, William,

1750. CORSBY, ——,

Northampton, 1780. Chiefly made Double-Basses. CORSBY, George. Lived

upwards of half a century in Princes Street, Leicester Square, where

he worked and dealt in old instruments. CRAMOND, Charles,

Aberdeen, 19th century. CRASK, George, Manchester.

He made a large number of instruments, chiefly imitations. CROSS, Nathaniel,

London, about 1700-50. Worked with Barak Norman. He made several

good Violins. Purfling narrow; excellent scroll. CROWTHER, John, 1760-1810. CUTHBERT, London,

17th century. Maker of Viols and Violins. Many of the latter have

merit. Model flat, and wood of good quality. Very dark varnish. DAVIDSON, Hay, Huntley,

1870. DAVIS, Richard. Worked

with Norris and Barnes. DAVIS, William, London.

Succeeded Richard Davis in the business now carried on by Edward

Withers. DEARLOVE, Mark, Leeds. DELANY, John, Dublin.

Used two kinds of labels, one of them very small— DENNIS, Jesse, London,

1805. DEVEREUX, John, Melbourne.

When in England he worked with B. Simon Fendt. DICKINSON, Edward,

London, 1750. Made instruments of average merit. The model is high. DICKESON, John, 1750-80,

a native of Stirling. He would seem to have lived in various places,

some instruments dating from London and some from Cambridge. He

was an excellent workman, and chiefly copied Amati. His work much

resembles that of Cappa. DITTON, London, about

1700. Mention is made of an instrument by this maker in Tom Britton's

Catalogue. DODD, Thomas, son

of Edward Dodd, of Sheffield. He was not a maker of Violins. Numerous

instruments bear his name, but they are the work of John Lott and

Bernard Fendt. The merit of these instruments is of the highest

order, and they are justly appreciated by both player and connoisseur.

Thomas Dodd deserves to be mentioned in terms of high praise, notwithstanding

that the work was not executed by him, for his judgment was brought

to bear upon the manufacture during its various stages, and more

particularly in the varnishing, in which he took the liveliest interest.

He had a method of mixing colours, the superior qualities of which

he seems to have fully known, if we may judge from the note on his

labels, which runs thus: "The only possessor of the recipe

for preparing the original Cremona varnish. Instruments improved

and repaired." This undoubtedly savours of presumption, and

is certainly wide of the truth. Nevertheless there is ample evidence

that the varnish used by Thomas Dodd was very excellent, and had

a rich appearance rarely to be met with in instruments of the English

school. Dodd was encouraged in the art of varnish-making by persons

of taste, who readily admitted the superior qualities of his composition,

and paid him a handsome price for his instruments. He was thus enabled

to gratify his taste in his productions by sparing no means to improve

them. He ultimately attained such a reputation for his instruments

as to command no less a sum than �40 or �50 for a Violoncello. Commanding

such prices, it is evident that he spared no expense, or, what was

to him a matter of still greater importance, no time. He was most

particular in receiving the instruments in that incomplete stage

known in the trade as "in the white," i.e.,

without varnish. He would then carefully varnish them with his own

hands, guarding most warily the treasured secret of the composition

of his varnish. That he never departed from this practice may be

inferred from the fact that the varnish made by the workmen in his

employ, apart from the establishment, for their own instruments,

is of an entirely different stamp, and evidently shows that they

were not in their master's secrets. The instruments bearing

the Dodd label are not valued to the extent of their deserts, and

there can be but little doubt that in the course of time they will

be valued according to their true merits. They were made by men

of exceptional talent, who were neither restricted in price nor

material. Under such favourable conditions the results could not

fail to be good. DODD, Thomas, London.

Son of Thomas Dodd, musical instrument dealer, of St. Martin's Lane.

The father, although not a maker of Violins, possessed excellent

judgment, both as regards work and makers, which enabled his son

to profit considerably during his early years whilst working with

Fendt and Lott. DORANT, William,

London, 1814. DUKE, Richard, worked

from 1750-80. The name of this maker has long been a household word

with English Violinists both amateur and professional. Who has not

got a friend who is the fortunate owner of a veritable "Duke"?

The fame of His Majesty Antonio Stradivari himself is not greater

than that of Richard Duke in the eyes of many a Fiddle fancier.

From his earliest fiddling days the name of Duke became familiar

to him; he has heard more of him than of Stradivari, whom he somehow

confuses with Cremona. He fondly imagines that Cremona was a celebrated maker,

and Stradivari something else; inquires, and becomes more confused,

and returns again to "Duke," with whom he is thoroughly

at home. Many excellent judges

have wondered how it came to pass that Richard Duke should have

been so highly valued, there being, in their estimation, so little

amongst his remains worthy of the reputation he gained. The truth

is that no maker, with the exception of the great Cremonese artists,

has been so persistently counterfeited. The name of Duke has been

stamped upon every wretched nondescript, until judges who had not

the opportunity of seeing the genuine article mistook the copies

for the original, and hence the confusion. When, however, a really

fine specimen of Duke is once seen, it is not likely to be forgotten.

As copies of Amati such instruments are scarcely surpassed, varnish,

work, and material being of the best description. The copies of

Stainer were not so successful. DUKE, Richard, London.

Son of the above. DUNCAN, ——,

Aberdeen, 1762. DUNCAN, George, Glasgow,

contemporary. EGLINGTON, ——,

London, 1800. EVANS, Richard, London,

1750. His label is a curiosity— FENDT, Bernard, born

at Innsbruck, in the Tyrol, 1756, died 1832. He was evidently a

born Fiddle-maker, genius being stamped, in a greater or less degree,

upon all his works. To Thomas Dodd belongs the credit of bringing

his talent into play. Dodd obtained the services of Fendt upon his

arrival in England, which the latter reached at an early age. He

remained with Dodd many years, frequently making instruments with

John Frederick Lott. The instruments so made bear the label of Thomas

Dodd. Lott being also a German, reciprocity of feeling sprung up

between him and Fendt, which induced Lott to exchange the business

to which he was brought up for that which his fellow countryman

Fendt had adopted, and henceforth to make Violins instead of cabinets.

By securing the services of these admirable workmen, Dodd reaped

a rich harvest. He found in them men capable of carrying out his

instructions with an exactness that could not be surpassed. Dodd

was unable to use the tools himself; but in Fendt and Lott he had

men who were consummate masters of them. When the instruments were

finished, as far as construction was concerned, they were clothed

in coats of the master's livery—"Dodd's varnish,"

the secret of making which he kept carefully to himself. With these

coats of varnish upon them the work was doubly effective, and every

point of excellence was made to shine with the happiest effect.

Upon leaving the workshop of Thomas Dodd, Bernard Fendt worked for

John Betts, making many of those copies of Amati which are associated

with the name of Betts, and which have so high a value. Although Fendt was

German by birth, his style of work cannot be considered as German

in character. Having early quitted his post of trade in Paris for

England, and having in this country placed himself under the guidance

of Dodd, who steadfastly kept before his workmen the originals of

the great Italian masters for models, his work acquired a distinctive

stamp of its own, and in its turn gave rise to a new and independent

class of makers. FENDT, Bernard Simon,

London, born in 1800, died in 1852. Son of the above. He was an

excellent workman. It is to be regretted that he did not follow

the excellent example set by his father, and let time do its work,

without interruption, upon his instruments. Had he done so they

would, in many instances, have been equal to those of his parent;

but, unfortunately, he worked when the mania for obtaining supposed

maturity by artificial means was at its height, and shared the general

infatuation, and, in consequence, very frequently destroyed all

the stamina of his instruments. Subsequently he became a partner

of George Purdy, and carried on a joint business at Finch Lane,

in the City of London, from whence most of his best instruments

date. Purdy and Fendt had also a shop in the West End about 1843.

He was a most assiduous worker. The number of Violins, Tenors, Violoncellos,

and Double-Basses that he made was very great; indeed, his reputation

would have been greater had he been content to have made fewer instruments

and to have exercised more general care. His copies of Guarneri

are most numerous, numbering some hundreds. They are mostly varnished

with a glaring red colour, of a hard nature. He made many good Double-Basses

of the Gasparo da Sal� form, the varnish on which is superior to

that on his Violins. He made also an excellent quartette of instruments—Violin,

Viola, Violoncello, and Double-Bass—for the Exhibition of

1851. They were certainly the best contemporary instruments exhibited,

but he failed to obtain the prize medal. FENDT, Martin, London,

born 1812, died 1845. Brother of the above. Worked for Betts. FENDT, Jacob, London,

born 1815, died 1849. Third son of Bernard Fendt. The best maker

among the sons of Bernard. His instruments are beautifully finished,

and free from the stereotyped character belonging to those of his

brother Bernard. As specimens of the imitator's art they are unsurpassed.

One cannot but regret that such a consummate workman should have

been obliged to waste his energies in making new work resemble that

of a hundred years before. The patronage that he obtained was not

of much value, but had he brought his work into the market in its

natural condition he could not have lived by his trade. He was,

therefore, compelled to foster that which he no doubt felt to be

degrading. The copies of Stradivari by Jacob Fendt are among his

best efforts. The work is well done; the discoloration of the wood

cleverly managed, the effects of wear counterfeited with greater

skill than had ever been done before, and finally, an amount of

style is thrown into the work which transcends the ingenuity of

any other copyist. Had he been allowed to copy the form of the old

masters, as Lupot did, without imitating the actual wear of the

instrument, we should have had a valuable addition to our present

stock of instruments of the Panormo class. FENDT, Francis, London.

Fourth son of Bernard; also worked in Liverpool about 1856. FENDT, William, London,

born 1833, died 1852. Son of Bernard Simon Fendt. Was an excellent

workman, and assisted his father in the manufacture of several of

his Double-Basses. FERGUSON, Donald,

Huntley, Aberdeenshire. FIRTH, G., Leeds,

1836. FORSTER, William,

born in 1713, died 1801. The family of the Forsters have played

no unimportant part in the history of Violins. The attention they

commanded as makers, both from artists and amateurs, has probably

never been equalled in England. Their instruments claimed attention

from the moment they left their makers' hands, their construction

being excellent in every way. William Forster was a native of Brampton,

in Cumberland, where he followed the trade of a spinning-wheel maker,

occupying his spare time in the making and repairing of Violins

and musical instruments generally. His labours, as far as they relate

to Violin-making, appear to have been of a very unpretending nature,

but they served to impart a taste for the art to his son William,

who was the best maker of the family. FORSTER, William,

London, born 1739, died 1807. Son of William Forster mentioned above.

Worked with his father at Brampton in Cumberland, making spinning-wheels

and Violins—two singularly diverse occupations. It was, however,

to the latter industry he gave the most attention, and he soon became

the great maker of the neighbourhood. He afterwards added another

string to his bow, viz., that of playing country-dances at the village

festivities. Thus armed with three occupations, he must have been

well employed. He seems to have early discovered that his abilities

required a larger field in which to show themselves to advantage,

and accordingly took the usual course in such circumstances—came

to the Metropolis, in which he settled about the year 1759. He soon

obtained employment at a musical instrument seller's on Tower Hill,

and gave up, then and for ever, the making of spinning-wheels, while

by throwing all his soul into the manufacture of Violins he soon

gave his master's patrons the highest satisfaction. He ultimately

commenced business on his own behalf in the neighbourhood of Duke's

Court, St. Martin's Lane, where his abilities attracted considerable

attention, and secured him the patronage of the dilettanti in

the musical world. For several years he followed the path trodden

by the makers of the period, and copied Stainer. His instruments

of this date are very excellent both in workmanship and material,

but are not equal to those of the Amati pattern, which he commenced

to make about the year 1770. These are beautiful works, and have

a great charm from their being so varied. Some are copies of Antonio

and Girolamo Amati, variously modelled; others are copies of Niccol�

Amati. The wood and varnish also vary very much, but the high standard

of goodness is well maintained throughout. His varnish was, during

the last twenty years of his life, very fine in quality, and in

the manufacture of it he is said to have been assisted by a friend

who was an excellent chemist. He made only four Double-Basses, three

of which were executed for the private band of George III. Forster's

instruments were the favourite equipment of Robert Lindley, and

their value in his day was relatively far higher than at the present

moment. When Lindley died attention was turned to Italian Violoncellos,

and a vast number having been brought to England, the value of Forster's

productions was very considerably depreciated; now, however, that

the cultivation of stringed instrument music has been so much extended,

they are rapidly rising again to their former level, Italian instruments

being a luxury not obtainable by every one, and age having so benefited

the tone of Forster's Violoncellos as to render them excellent substitutes. FORSTER, William,

London, born in 1764, died 1824. Son of William Forster, the second

of the family. Although this maker did not attain to the celebrity

of his father, his instruments are often fully as good. The workmanship

is very neat, and the modelling excellent, the varnish being equal

to that on his father's instruments. FORSTER, William,

London, born in 1788, died 1824. Son of William Forster, mentioned

above. He was a very good workman: he made but few instruments. FORSTER, Simon Andrew,

London, born in 1801, died about 1870. Brother of William, mentioned

above. He learned his business from his father and Samuel Gilkes,

who worked for William Forster. He made several instruments between

the years 1828 and 1840, which are of average merit. Best known

as joint author with W. Sandys of a "History of the Violin"

(London, 1864). FRANKLAND, ——,

London, about 1785. FURBER, ——,

London. There were several makers of this family, some of whom worked

for Betts, of the Royal Exchange. Many of their instruments are

excellent, and should unquestionably be more valued than they are.

John Furber made several Violins of the grand Amati pattern, and

also copied with much ability the "Betts" Stradivari,

when the instrument belonged to Messrs. Betts in the Royal Exchange,

for whom he worked. FURBER, Henry John,

son of John Furber, London. He has made several excellent instruments,

and maintained the character for good workmanship which has been

associated with the name of Furber for upwards of a century. GIBBS, James, 1800-45.

Worked for Samuel Gilkes and others. GILKES, Samuel, London,

born in 1787, died in 1827. Was born at Morton Pinkney, in Northamptonshire.

He became an apprentice of Charles Harris, whose style he followed

to some extent. Upon leaving Harris he engaged himself to William

Forster, making many instruments for him, retaining, however, all

the features of the style of Harris. In the year 1810 he left the

workshop of Forster, and commenced business on his own account in

James Street, Buckingham Gate, where the few instruments bearing

his name were made. Too much cannot be said in praise of much of

the work of this excellent maker. The exquisite finish of many of

his instruments evidences that the making of them was to him a labour

of love. Amati was his favourite model. GILKES, William,

London, born 1811, died 1875. Son of Samuel Gilkes. Has made a great

number of instruments of various patterns, chiefly Double-Basses. GOUGH, Walter. An

indifferent workman. HARBOUR, ——,

London, about 1785. HARDIE, Matthew,

Edinburgh, date from about 1800. He was the best maker Scotland

has had. The model is that of Amati; the work throughout excellent.

The linings are mostly of cedar. He died about 1825-26. HARDIE, Thomas, Edinburgh.

Worked with his father, Matthew Hardie. He was born in 1804, died

1856. HARE, John, London.

About 1700. His label shows that he was in partnership, his name

being joined to that of Freeman, and the address is given as "Near

the Royal Exchange, Cornhill, London." Much resembles the work

and style of Urquhart. Varnish of fine quality. HARE, Joseph, London,

probably a son of John Hare, above-mentioned. Varnish of excellent

quality. HARRIS, Charles,

London, 1800. This maker is known only to a few dealers, as he made

chiefly for the wholesale merchants of his day. His name was rarely

affixed to his instruments, but those thoroughly acquainted with

his work agree in giving him a foremost place among the makers of

this country. He was, like many other makers of that period, engaged

in two occupations differing very much from each other, being at

the same time a Custom-house officer and a maker of Violins. The

former circumstance brought him into contact with mercantile men,

and enabled him to obtain commissions to make Violins for the export

trade. His business in this direction so increased that he obtained

the services of his relative, Samuel Gilkes, as his assistant. He

never aimed at producing a counterpart of the instrument that he

copied by resorting to the use of deleterious means to indicate

upon the surface of an instrument the ravages of time. He faithfully

copied the form, and thus did what Lupot was doing at the same period.

The finish of these instruments is excellent, and as they are covered

with a good quality of varnish, they have every recommendation of

appearance. HARRIS, Charles.

Son of the above. Neat workmanship. Well-cut scroll. Sound-holes

not well formed. Yellow varnish. Worked for a short time for John

Hart.

HART, John Thomas,

born December 17, 1805, died January 1, 1874. He was articled to

Samuel Gilkes in May, 1820, of whom he learned the mechanical branch

of his profession. He afterwards centred his attention upon the

peculiar characteristics of the Cremonese and Italian Violin-makers

generally, and in a comparatively brief space of time obtained an

extensive acquaintance in that direction. His unerring eye and powerful

memory of instruments once brought under his notice secured for

him the highest position among the connoisseurs of his time. Commencing

business at a period when the desire to possess instruments by the

famous Italian makers was becoming general among amateurs, and being

peculiarly fortunate in securing an early reputation as a judge

of them, he became the channel through which the greater part of

the rare Italian works passed into England, and it has frequently

been said that there are very few distinguished instruments in Europe

with which he was unacquainted. Among the remarkable collections

that he brought together may be mentioned that of the late Mr. James

Goding, the remnant of which was dispersed by Messrs. Christie and

Manson in 1857; the small but exquisite collection of Mr. Charles

Plowden, consisting of four Violins of Stradivari and four of Guarneri,

with other instruments of less merit, the whole of which again passed

into Mr. Hart's possession upon the death of their owner; and, lastly,

a large portion of the well-known collection of the late Mr. Joseph

Gillot, sold by Christie and Manson shortly after the famous sale

of pictures belonging to the same collector. HAYNES, Jacob, London,

1746. Copied Stainer. The style resembles that of Barrett. HEESOM, Edward, London,

1748. Copied Stainer. HILL, Joseph, London,

1715-84. Pupil of Peter Wamsley. His Violoncellos and Tenors are

well-made instruments. HILL, William, London,

1741. Son of the above. Very good work. HILL, Joseph, London,

1800-40. Son of the above. HILL, Lockey, London,

1800-35. Brother of the above. Made many excellent instruments. HILL, William Ebsworth,

London, 1817-95. Son of Lockey Hill. Made several instruments in

his younger days, but, like the rest of our English makers, he long

since discovered that new work was unremunerative, and turned his

attention to repairing and dealing in old instruments, and became

the founder of the well-known firm of W. E. Hill and Sons, of Bond

Street. He exhibited at the Exhibition of 1862 a Violin and Tenor,

thus showing that Violin-making was not quite extinguished in England. HOLLOWAY, J., London,

1794. HUME, Richard, Edinburgh,

16th century. A maker of Lutes, &c. JAY, Henry, London,

17th century. Maker of Viols, which are capital specimens of the

work of the period. The varnish is excellent. JAY, Thomas, London.

Related to the above. Excellent work. JAY, Henry, London,

about 1744-77. A maker of Kits chiefly. At this period these juvenile

Violins were in much demand by dancing-masters. A few years ago

a very choice collection of these instruments was made by an Irish

gentleman residing at Paris, who obtained specimens from all parts

of Europe. Henry Jay also made Violoncellos, some of which have

the names of Longman and Broderip on the back. JOHNSON, John, London,

1750. The Violins bearing his label are dated from Cheapside. Johnson

was a music and musical instrument seller. In "The Professional

Life of Dibdin," written by himself, we have the following

reference to this City music-seller: "My brother introduced

me to old Johnson, who at that time kept a capital music-shop in

Cheapside.1 I soon, however, grew tired of an attendance

on him. He set me down to tune Harpsichords, a mere mechanical employment,

not at all to my taste." "I saw plainly that I might have

screwed up Harpsichords in old Johnson's shop to all eternity, without

advancing my fortune; and as to the songs and sonatas that I brought

him for sale, they had not been performed at the theatres nor Vauxhall,

nor any other place, and Johnson would not print them." "The

Thompsons, however, of St. Paul's Churchyard, published six ballads

for me, which sold at three-halfpence a-piece, and for the copyright

of which they generously gave me three guineas." Though we

may not feel disposed to apply the term "generous" to

a payment of half-a-guinea for a Dibdin ballad, yet in all probability

we are indebted to the Thompsons for this particular recognition

of merit. Happily true genius, when in straits, generally finds

relief. Were it otherwise, and had the Thompsons been as deaf to

Dibdin as John Johnson appears to have been, "Tom Bowling,"

"Poor Jack," and many other compositions of sterling merit,

might never have been written.2 1 Dibdin's brother

was captain of a merchant vessel, and was intimate with Johnson

the music-seller. On the death of Captain Dibdin his brother composed

"Tom Bowling," the music and words of which bespeak the

fraternal love of the composer. 2 Dibdin was evidently

discouraged in consequence of Johnson's refusal to publish his songs:

he says, "After I had broken off with Johnson, I had some idea

of turning my thoughts to merchants' accounts—the very last

thing upon earth for which I was calculated." KENNEDY, Alexander,

London, 1700-86. Was a native of Scotland. He was the first maker

of Violins in his family, which was connected with the manufacture

for nearly two centuries. KENNEDY, John, London,

born 1730; died 1816. Nephew of Alexander Kennedy. Made Violins

and Tenors. KENNEDY, Thomas,

London, born 1784; died about 1870. Son of the above. Probably made

more instruments than any English maker, with the exception of Crask. LENTZ, Johann Nicolaus,

London, 1803. He used mostly one kind of wood, viz., close-grained

maple. Varnish nearly opaque. LEWIS, Edward, London,

1700. The work is well executed throughout, and the varnish superior. LISTER, George, 18th

century. LONGMAN AND BRODERIP,

Cheapside, London, about 1760. They were music-publishers and instrument-sellers,

and were not Violin-makers. Benjamin Banks, Jay, and others, made

many of the instruments upon which the name of Longman is stamped.

Muzio Clementi was at one time a partner in the firm. The business

ultimately passed to Collard and Collard. LOTT, John Frederick,

1775-1853. Was a German by birth. He was engaged in the cabinet

business early in life. He was induced by Fendt to turn his attention

to making Violins, and ultimately obtained employment under Thomas

Dodd, making many of the Violoncellos and Double-Basses that carry

the label of Dodd within them. His work was of a most finished description.

His Double-Basses are splendid instruments, and will bear comparison

with Italian work. His varnish was far from equal to his finish.

The time he spent in making these instruments was double that which

any other English maker expended over similar work. There is not

a single portion of any of his Double-Basses that has been carelessly

made; the interior is as beautifully finished as the exterior. The

machines on many of his Basses were made by himself—a very

unusual circumstance. The scrolls are finely cut. He was certainly

the king of the English Double-Bass makers. LOTT, George Frederick,

London, born 1800; died 1868. Son of the above. Many years with

Davis, of Coventry Street. Was an excellent judge of Italian instruments,

and a clever imitator. LOTT, John Frederick,

London, younger brother of the above, died about 1871. Was articled

to Davis. Has made many clever imitations. He was also an ardent

lover of Cremonese instruments, and thoroughly understood their

characteristics. His career was both chequered and curious, sufficiently

so, indeed, to cause our eminent novelist, Charles Reade, to make

it the subject of "Jack of all Trades: a Matter-of-Fact Romance."

Jack Lott (as he was familiarly styled) therefore shares with Jacob

Stainer the honour of having supplied subject-matter for writers

of fiction. It must, however, be said that whilst Dr. Schuler's

"Jacob Stainer" is mainly pure fiction, "Jack of

all Trades" is rightly entitled "a matter-of-fact romance."

I have many times heard John Lott relate the chief incidents so

graphically described by Charles Reade. MACINTOSH, Dublin.

Succeeded Perry and Wilkinson. Died about 1840. MARSHALL, John, London,

1750. MARTIN, ——,

London, about 1790. MAYSON, Walter H.,

Manchester, 1835-1904. A prolific maker. His later work is highly

spoken of. MEARES, Richard,

about 1677. Maker of Viols. MIER, ——,

London, about 1786. MORRISON, John, London,

about 1780-1803. NAYLOR, Isaac, Headingly,

near Leeds, about 1778-92. NICHOLS, Edward,

18th century. NORBORN, John, London,

about 1723. NORMAN, Barak, London,

1688-1740. The instruments of this maker are among the best of the

Old English school. His instructor in the art of Viol and Violin-making

is unknown, but judging from the character of his work it is very

probable he learned from Thomas Urquhart. This opinion is strengthened

upon examining his earliest instruments. We there find the same

peculiarities which mark the individuality of Urquhart. Later in

life he leaned much to the model of Maggini. During his early

years he was much esteemed as a maker of Viols, many of which have

all the marks of careful work upon them. On all of these instruments

will be found his name, surrounded with a design in purfling, under

the finger-board, or his monogram executed in purfling. The same

trade token will be found in his Violoncellos. All endeavours to

discover any existing English Violoncello, or record of one, anterior

to Barak Norman, have failed, and, consequently, it may be assumed

that he was the first maker of that instrument in England. Here,

again, is evidence of his partiality for the form of Maggini, as

he copied this maker in nearly all his Violoncellos. All the Violoncellos

of Barak Norman have bellies of good quality; the modelling is executed

skilfully, due care having been observed in leaving sufficient wood.

His Tenors are fine instruments. Many of these were made years before

he began the Violoncellos—a fact which satisfactorily accounts

for the marked difference in form peculiar to them. The build is

higher, and the sound-hole German in character; the varnish is very

dark. About the year 1715 Barak Norman entered into partnership

with Nathaniel Cross, carrying on the joint business at the sign

of the Bass Viol, St. Paul's Churchyard. In a Viol da Gamba which

belonged to Walter Brooksbank, Esq., of Windermere, is a label in

the handwriting of Nathaniel Cross, in which he adds the power of

speech to the qualities of the quaint Gamba; the words are, "Nathaniel

Cross wrought my back and belly," the sides and scroll being

the work of his partner. NORRIS, John, London,

born 1739; died 1818. Articled to Thomas Smith, the successor of

Peter Wamsley. Similar work to that of Thomas Smith. He became a

partner of Robert Barnes. PAMPHILON, Edward,

London, 17th century. The Violins of this maker were formerly much

prized. The model is very high, and the appearance somewhat grotesque.

It is to be regretted that the splendid varnish often found on these

instruments was not put upon better work. PANORMO, Joseph,

London. Son of Vincent Panormo. His work was excellent. His Violoncellos

are decidedly superior to his Violins. PANORMO, George Lewis,

London. Brother of the above. Made Violins of the Stradivari pattern. PANORMO, Louis, London.

Made Guitars chiefly. PARKER, Daniel, London,

18th century. This is another maker of the English school, who was

possessed of exceptional talent, and whose instruments are well

worthy of attention from those in search of good Violins at a moderate

cost. To Parker belongs, in conjunction with Benjamin Banks, the

merit of breaking through the prejudice so long in favour of preference

for the Stainer model. The dates of his

instruments extend from the year 1740 to 1785. He left his Violins

thick in wood, which has certainly enhanced their value now that

time has ripened them. He used excellent material, which is often

very handsome. The varnish is of a mellow quality, and fairly transparent.

A large number of these Violins have been passing under other makers'

names, and have been but little noticed. PEARCE, James, London,

18th century. PEARCE, W., London,

contemporary. PEMBERTON, Edward,

London, 1660. This maker has been often mentioned as the author

of a Violin said to have been presented to the Earl of Leicester

by Queen Elizabeth, and to suit this legend Pemberton's era has

been put back a century. The date given above will be found in the

Violins of this maker. PERRY AND WILKINSON,

Dublin, 17— to 1830. The instruments bearing the labels of

these makers are frequently excellent in tone, material, and finish. POWELL, Thomas, London,

18th century. PRESTON, London,

about 1724. Appears to have used his trade label in the instruments

he sold, made by makers he employed. PRESTON, John, York,

18th century. RAWLINS, Henry, London,

about 1781. He appears to have been patronised by Giardini, the

Violinist, according to the label here given. Giardini held the

post of leader at the Italian Opera at this period. RAYMAN, Jacob, London,

17th century. The subject of this notice was probably a German,

from the Tyrol, who settled in England about 1620, and may be considered

as the founder of Violin-making in this country, there being no

trace of any British Violin-maker previous to that time. His work

is quite different from that of the old English Viol-makers. The

instruments of Rayman are of a somewhat rough exterior, but full

of character. The form is flat, considering the general style of

the work. The sound-holes are striking, although not graceful in

any way. The scroll is diminutive, but well cut. The varnish is

very fine. In the catalogue of the effects of Tom Britton, mention

is made of "an extraordinary Rayman." RICHARDS, Edwin,

London, contemporary. Maker and repairer. ROOK, Joseph, Carlisle,

about 1800. ROSSE (or Ross),

John, Bridewell, London, about 1562. Made Viols and Bandoras. ROSS, John, London,

about 1596. Son of the above. Maker of Viols. The varnish is excellent

in quality. SHAW, London, 1655.

Viol maker. SIMPSON, London,

1785. SMITH, Henry, London,

1629. Maker of Viols. SMITH, Thomas, London.

Pupil of Peter Wamsley, and his successor at the Harp and Hautboy. SMITH, William, London,

about 1770. TARR, William, Manchester.

Made many Double-Basses from about 1829. TAYLOR, London, about

1800. A maker of much merit. Instruments of the character of Panormo. THOMPSON, London,

1749. THOROWGOOD, Henry,

London. Little known. TILLEY, Thomas, London,

about 1774. TOBIN, Richard, London,

1800. Pupil of Perry, of Dublin. His instruments are much appreciated

by the best judges. In cutting a scroll he was unequalled amongst

English makers. TOBIN, London. Son

of the above. URQUHART, London,

17th century. Nothing is known concerning the history of this excellent

maker. The style may be considered as resembling that of Jacob Rayman,

and it is possible he worked with him. His varnish is equal to that

on many Italian instruments. VALENTINE, William,

London, died about 1877. Made many Double-Basses for Mr. Hart, which

are highly valued. WAMSLEY, Peter, London,

18th century. One of the best English makers. His copies of Stainer

are very superior. WISE, Christopher,

London, about 1650. Yellow varnish, neat workmanship, flat model,

small pattern. WITHERS, Edward,

Coventry Street. Succeeded William Davis. WITHERS, Edward.

Son of the above. Wardour Street, Soho. Was instructed by John Lott. YOUNG, London, about

1728. Lived in St. Paul's Churchyard. Purcell has immortalised father

and son in the first volume of his Catches.

CONTENTS

SECTION

V.—THE GERMAN SCHOOL AND MAKERS SECTION

VI.—THE ENGLISH SCHOOL AND MAKERS SECTION

VII.—THE VIOLIN AND ITS VOTARIES. SKETCH OF THE PROGRESS

OF THE VIOLIN

|