|

|

|

PREFACE

The

inquiry which took me to Russia last year had an economic rather than a

political character. Within a very short space of time, however, it became

evident that very little progress could be made with the former aspect until I

had become conversant with the political conditions of the New Russia, so

entirely at variance with the old, and thus be in a position to gauge their

effects economically upon this country.

The study so made, as day by day the

extraordinary kaleidoscopic events passed before the eyes, proved of absorbing

interest, and left me deeply impressed with their extreme importance alike to

this country and to Russia herself. The occurrences which led directly to the

present position are set down in diary form in these pages. I have refrained from

criticism. For the sequence of events appears to furnish its own answers to the

thoughtful man.

But in the national interests the diary has a

further object. It is of the highest importance that the true causes for the

present appalling condition of Russia should be understood, and the question be

regarded with that breadth of view and the clarity and coolness in passing

judgment with which our race has become credited by the foreigner.

At present there is a strong

feeling amongst the peoples of the Entente that Russia has “ let us in.”

That the loss of the Eastern front has proved a

disaster of the first magnitude is obvious to all. As a direct consequence we

are now engaged upon the greatest battle in history and fighting for our lives,

or, which we value more, our national honour.

I leave it to my readers to decide whether, given

the conditions which of necessity followed the gigantic upheaval caused by the

Revolution amongst a totally uneducated people of so vast an empire, we could

or should have expected Russia to be able to maintain her fronts, which held up

nearly half the Austro-German divisions, without direct help from her Allies.

Germany conquered the Eastern front by

propaganda, not by force of arms. This propagandist campaign was carried on

absolutely unchecked and unopposed by the Allies.

At the end of two and a half years of war German

methods were well known. Should not the Entente have assisted their Ally in

both the German fields of warfare— force of arms by force of arms and

propaganda by propaganda?

E. P. Stebbing.

Hawthornden,

Midlothian.

April

8th, 1918.

Since the above went to press I have deemed it

advisable to add a few remarks on the present position of Russia. What is that

position ? Germany is the master of-Russia. She is already tearing up her peace

treaties—more scraps of paper—with the Ukraine and Russia, and appearances

point to Finland soon finding herself in a similar plight to the Ukraine. We

hesitated to recognise the Finnish Republic. Sweden

refused to help her against the Bolsheviks, and when the Entente in their turn

were appealed to the same course was followed, and food cargoes were stopped

from reaching her. Finland then applied to Germany, and armed help was at once

forthcoming. Food was also promised, but of course it has not been sent. As a

consequence of Entente inaction the new ice-free port at the head of the Murman railway is now imperilled.

As regards the present position of Germany in the

East, Professor Troeltsch, of Heidelberg, recently

described it as follows : “ We have achieved a military tenable frontier for

Central Europe towards the East and, on the other hand, we have created a girdle

of buffer States which stretches from Finland to the Caucasus, follows the

whole front of the Central Powers and, in the East, already stretches out to

Persia as the last link in the chain.” This is overstating the position, but it

does not leave the German aims in much doubt, and has a very plain significance

for us. We have been carrying out an arduous campaign in Mesopotamia,

sacrificing lives and treasure, with the object of putting an end to Germany’s

Berlin- Constantinople-Bagdad-Persian Gulf Railway scheme, with its direct

threat to India. In this campaign we have been successful, and we had begun to

regard that German dream as disposed of. But it has been replaced by a new one,

which she is busily fashioning into a semblance of reality. With the loss of

the Eastern front Roumania was left in the lurch and

is now under the German heel, bound by the most callous, brutal and rapacious

treaty ever conceived in modem times. Constanza, the fine Roumanian

port, is thus at Germany’s mercy. By the Brest-Litovsk treaty Russia was forced

to concede to the moribund Turk the rich district of Kars and Batum. Germany

had not given up her Indian dream ! This province wrested from Russia, and

Persia (where she is very active and has the Turks as her pioneers) are meant

to take the place of her lost trade and conquest route to the domination of

Asia. Her new route to the East is to be Berlin-Constanza-Batum-Baku, and then

across the Caspian and through Persia to the Persian Gulf. To assist her in

carrying out this purpose she is preparing to seize and retain for herself the

rich mineral wealth of the Urals and Caucasus and to make the Caspian, like the

Baltic, a German lake. Germany has a long way to go yet to realise

her new object; but so have we to defeat it. It is therefore imperative that

the British Empire peoples should realise her Eastern

aims. For otherwise our Mesopotamian and other campaigns will have been fought

in vain. Do we yet, as a nation, realise the position

?

We, a World Empire, invented the expression “

sideshows,” by which we more or less contemptuously designated the Egyptian,

Gallipoli, Mesopotamian and Macedonian campaigns. And the Russian front was

the affair of the Russians. Co-ordination of fronts amongst the Allies,

admittedly a difficult problem, was almost nonexistent ; if we except the

first year of the war, when the Russians in East Prussia and Galicia gallantly

drew on themselves the brunt of the enemy attacks, and so saved the French and

small British force from what might well have proved annihilation. We did not

then understand that we were fighting an enemy with one front only. “ Why waste

money and lives on side-shows ? ” was the phrase on every one’s

lips a couple of years ago, in ignorance of the fact that for our Empire these

“ sideshows ” were of paramount importance, that the Eastern fronts were vital

to our future existence as an Empire. Have we yet realised

this ?

That Germany can be left to enjoy spoils obtained

by a false propaganda combined with a callous premeditated treachery; that she

can be left to bring permanent misery and hardship into the homes of millions

of men and women who are, or were, our Allies, is unthinkable. The Allies have

played some wrong cards, but the rubber is not yet lost. But to win it the Germans

must be ousted from Russia and the East.

The Bolsheviks have done the world one good turn.

For they forced or entrapped Germany into showing her hand and displaying, yet

once again, the treatment meted out to all who fall beneath the ruthless Prussian

heel.

We have quitted Russia. Withdrawn our Embassy,

evacuated our naval and military staffs from Archangel, Kola and elsewhere,

and, with a few exceptions, recalled all Britishers, civilian, soldier and

sailor, who were representing us and working for us and for Russia in that

country. The American Embassy, in spite of Bolshevik and German protests,

remained; the French military mission remained; and other foreign Embassies

have since returned. Was it a wise policy on our part to leave Russia? Would it

not have been wiser to have withdrawn to the south, to that part of the country

occupied by our Russian friends—those friends who have been watching us with

such anxious eyes: to have remained, even if at some risk? Is “playing for

safety ” the right kind of fight, even from the merely materialistic point of

view, to put up after nearly four years of war ? Was it not, in the case of

Russia, too much like waiting to see which way the cat would jump ? Was it not

an unfortunate miscalculation ? True, we could never seriously have considered

the possibility of allying ourselves with the present so-called “ Government ”

who do not represent Russia, a “Government” who have destroyed all that human

foresight and human skill (backward in Russia though they were) had built up.

But we are now chiefly concerned with thwarting German ambitions in Central

Asia and safeguarding the road to India, and every possible step should be

taken to achieve this end.

The greater bulk of the Russians liked and

admired us; and, as a nation, we have grown accustomed to regard ourselves as

the champions of the oppressed and weak. Have we occupied this position vis-h-vis

with Russia since she was confronted with the greatest moment in her history,

in her destiny? We have still many friends in Russia, and it is of vital

importance that we should, in order to retrieve our position there, leave no

stone unturned to get into touch with them at once. The position bristles with

difficulties : they need not frighten us. But these difficulties are only

solvable on the spot.

The British peoples are almost entirely ignorant

of the true issues involved in this Russian imbroglio, and Germany is making

extraordinary efforts, by confusing these issues, to keep them so. The British

do not understand the importance, the necessity to our Empire, of a strong and

friendly Russian Empire. And yet a dismembered and Germanised

Russia might well sound our death-knell as an Empire. For with Russia to

exploit at her will, Germany would grow wealthy again in a comparatively short

period, and would once again play, and this time, it is conceivable, play

successfully, for the World Stakes. Is there any one, acquainted with the

facts, prepared to say that this is an overdrawn statement of the position ?

Can the pacifist say so ? Germany, we know, would make peace to-morrow on the

Western front if the Allies agreed to recognise her

so-called “ peace ” treaties (annexation treaties is the true term) on the

Eastern front, and left her to work her own hard and ruthless will on the

unfortunate peoples from whom she has wrung them.

It behoves us, then, to

dally no longer, for we have a long leeway to make up, and it must be made up.

There are three points in Russia at which the

Allies should act, and act with vigour. In the north

at the ports of Alexandrovsk, at the head of the Murman Railway and Archangel, at the head of the

Archangel-Petrograd Railway; in the south-east at Vladivostock,

at the end of the Siberian Railway. In the north all true Russians would

welcome Allied intervention and occupation of the two ports and as much of the

railways as can be secured and held. The Germans have made no secret of their

northern aims. These ports were not included in the clauses of the Brest treaty

having reference to the Baltic ports, etc. But Admiral Kaiserling,

who arrived in Petrograd in charge of the German Naval Mission at the end of

last December, announced that he had been sent “ to establish German naval

bases at Alexandrovsk and Archangel ” ; from which,

we may infer, to operate against ourselves and the Americans—in fact, to

reproduce Zee- brugge and Ostend in this

northern region. If the Allies delay much longer this great northern region

will be occupied, and fairly easily held, by the Germans.

At Vladivostock in the

far south-east the question of Japanese intervention has been simmering since

August of last year. In this matter Germany has, by means of her

extraordinarily well-organised propaganda, attained a

success which must have been beyond even her hopes. She has successfully sown

dissension, or, we will say, hesitation, amongst the Allies; brought forth the

“ Yellow Peril ” bogey, and by its judicious use frightened, it would appear,

the Allies as much as the Russians. Japan has been credited with motives and

aims which her past loyalty to her Allies should alone have sufficed to

discredit. How much longer are we going to hesitate ? It is perfectly well

known that Germany is collecting together throughout Siberia her own and

Austrian prisoners; and these are certainly being reinforced by the

considerable numbers who, I discovered for myself, were quartered in the

eastern parts of the Archangel and Vologda Governments, which are linked up

with Central Russia and the Siberian Railway by the Kotlas-Viatka

Railway and waterways. These prisoners are being armed, and German officer

prisoners are organising them into divisions and

corps. And whatever his other disabilities, we are well aware that the German

officer is very efficient at his own job. In London and elsewhere efforts are

being made to belittle this danger. But it is useless waiting till it comes to

a head before recognising it, and then taking steps

to deal with it when too late. Up to now Colonel Semenoff

and his gallant Cossacks have been left to wage an unequal fight alone, but

there are evidences that he is gathering strength; for Russia now hates the

German as much or more than the Bolshevik. And the Czechoslovak troops are now

entering the arena. With the Allies advancing up the railway from Vladivostock there can be little doubt that the position

would alter for the better. But this advance must be made before the prisoners

of the Central Powers are organised into a striking

force capable of invading Siberia. For if Germany gets her grip on Siberia and

secures command of the Siberian Railway and the northern route via Kotlas and down the Northern Dvina to Archangel (for which

reason, amongst others, she wants that port), she will secure at once a great

granary and store of food-stuffs. It will be well, in view of the great organising ability of the Germans «nd

the surprises this war has held for the world, not to lay too great stress on

the difficulties of transportation which would face them. It is safer to give

the enemy the credit of being able to organise this

business. If it eventuated it wrould mean

the prolongation of the war for several years. For when beaten in her present

great offensive, Germany could retire towards or on the Rhine “ for strategic

reasons,” sit down and dispatch large forces to the East to exploit her

conquests and obtain stores of food and raw materials. Finally, the Allies have

an additional incentive far immediate action in the

accumulation of munitions and food-stuffs at Vladivostock

which must not be allowed to fall into German^hands.

So far we have landed a handful of men at the port !

This war, as we now all recognise,

can never be won without a co-ordination of the fronts in which all the Allies

should work, each up to her greatest possible output of ability, men and

material. . If we accept this dictum, Japan’s position and right to enter the

land war is indisputable, and her point of entry, equally indisputable, since

she is on the spot, is at Vladivostock. If we are

still so divided in opinion (i. e, unwelded)

as to make Japan’s entry a matter of susceptibilities—and it is here that

Germany has always played her strongest card in the past—the war to all

appearances will drag on for a number of years, and may end in disaster as the

outcome. Of one thing there can be no longer any doubt. Between the Bolshevik

and the German Siberia will be lost to the Allies unless they take prompt

action. We may accept it as probable that Russia, educated Russia, has learnt

her lesson from the failures, dissensions and vacillations of last year, to

which have been added the unspeakable horrors and misery of the Bolshevik

regime and the callous perfidy of the German. We are not yet in a position to

say how much of this lesson has been absorbed. But we do know the only way to

save her. Before this last road is barred to us by the German, should we not

make up our minds to take it ?

With each of the three forces operating from the

points mentioned, we should send men, as many as we can lay hands on, whose

business would be propaganda—propaganda against the German. It will not be

possible to give them any stereotyped orders. They must be trusted. Pick them

out, give them the order “ Propaganda ” in one word, and leave them to do the

job in their own way; and that way will be determined entirely by the nature of

each difficulty as it arises on the spot.

The object before us is to save the Russian

Empire from the German. If we fail in this the war will have to be fought out

again in the future.

E. P. S.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

ACROSS THE

NORTH SEA

TO PETROGRAD THROUGH SCANDINAVIA AND FINLAND

RUSSIA AFTER THE REVOLUTION (APRIL-JULY)

Resume of chief

events—Russian offensive on the southwestern front.

PETROGRAD IN THE LATTER HALF OF JULY

The Bolshevik outbreak—The Russians open their

front at Tamapol

The present position of Russia—The new Cabinet.

petrograd in august 1917 (continued)

The women soldiers—The Ukraine and Finnish

questions —The Stockholm Conference—The Soukhomlinoff trial.

petrograd in august 1917 (continued)

At

the Foreign Office—The exploitment of the Russian

forests—The Stockholm Conference—Transfer of ex-Czar to Siberia—The Moscow

Conference—The peasants’ difficulties and requirements.

petrograd in august 1917 (continued)

. . 124

Conferences at Moscow—The Russian and Roumanian

fronts—The Soukhomlinoff trial.

THE MOSCOW

CONFERENCE . . . .155

PETROGRAD IN SEPTEMBER................... 180

Retirement of Russians on Roumanian

front—Korniloff and the Government—The Germans and Riga—German propaganda.

ARCHANGEL AND THE NORTHERN DVINA

XII.

UP THE VICHEGDA—A GREAT

FOREST TRACT

RETURN

TO ARCHANGEL AND PETROGRAD

September 3rd-15th

The

loss of Riga and the Korniloff affair—The Soukhom- linoff trial

PETROGRAD

IN SEPTEMBER (continued)

The

proclamation of the Republic—The Viborg massacres —Question of Japan entering

the war on land—America and the war in the air—Resignation of Soviet officers—

Russia’s position in the war.

Growing

power of the Bolsheviks—The truth about the Korniloff

revolt—End of the Soukhomlinoff trial

PETROGRAD

IN SEPTEMBER AND OCTOBER

The

Democratic Conference—The Finnish question—The preliminary Parliament—Autonomy

for the Ukraine

THE

FALL OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT AND ADVENT OF THE BOLSHEVIKS

The

new coalition Cabinet—The Germans in the Baltic — Opening of the preliminary Parliament—The

advent of the Bolsheviks

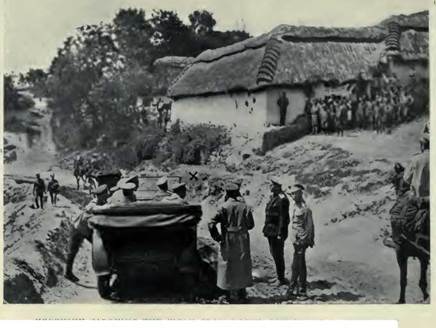

Kerensky in the trenches on the Eastern front, June 1917

The ephemeral “war ” town of Harparanda as seen from Tornea

Russian soldiers and sailors buying raspberries

from children at a way

Kerensky carrying the fiery cross round the front in June 1917

Kerensky addressing the troops at the front in June 1917

Kerensky in the trenches in June 1917

Kerensky addressing officers at the front in June 1917

Kerensky discussing the proposed offensive on the S. W. front in June 1917 43 A revolutionary procession passing the British Embassy in Petrograd .

Fuel barges in a canal in Petrograd.

The “Liberty Loan”—selling bonds from the boat

Kiosk in the Nevski,

The Commandant of the Women Soldiers’ Battalion and part of her troops 70 The Women Soldiers—a squad of recruits

A soap queue in Petrograd, August 1917

A decorated armoured car manned by soldiers and

girls starting out to

A common sight after the Revolution in Petrograd

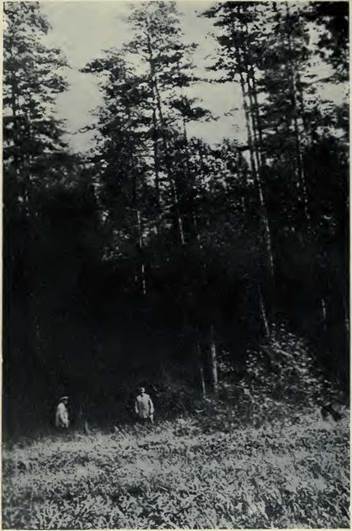

The great pine forests of Russia

The wooden jetties in Archangel

Unloading fuel at a d^pot on the Northern Dvina river

Barge loaded with Siberian cattle proceeding down

the Northeim Dvina

Tug towing a raft down an upper reach of the Northern Dvina

Fishing village and apparatus on the Northern Dvina River

The Church at Kotlas, Northern Dvina

Zaryanims and their boats on the Vichegda River, N.E. Russia

Church and scenery on the Vichegda Rive

General river-side view of Archangel..

A detachment of sailors from the Baltic Fleet

addressing the populace in

CHAPTER I

ACROSS THE NORTH SEA

There

are few of us, I suppose, who do not believe that the Great War has been a

blessing in disguise for the British race and for the British Empire. It has

acted upon us much in the same way as our bitter nor’-easter— bracing us all

up. A kill or cure business, eliminating the effete. And it is not, as has been

mostly the case in former wars, only the youngsters who have been able to bear

a hand in the game, as we are all by now well aware. Towards the end of the

second year of the war I remember hearing a man, a big fleshy man (a civilian

in peace time) of forty-five or thereabouts, who was wearing a captain’s stars

and serving somewhere in Britain, say to a friend : “Early in 1914 I had made

up my mind that I was getting into the sere and yellow and that for active

pursuits I was becoming passé." His opinion of himself had

undergone a remarkable change in the two war years. He continued, “ I now feel

thirty once more, and do not propose to consider the sere and yellow stage for

many years to come.” To how many^ must the war have brought this realisation! And it will be all to the good of the Empire

that the softness of living which produced this early ageing, in mind if not in

body, has been swept away.

This new aspect of the nation with regard to its

physical and mental fitness as the outcome of the war formed the burden of a

discussion which took place in a railway compartment in which several of us,

bound for Petrograd, were seated last July. The journey to Petrograd is no longer

the luxurious trip of the old days of peace. There were not many direct ways of

reaching the Russian capita] last year. The best known during the past year or

t\vo is probably the Archangel route. I shall have something^to say later on about this Russian port and its

extraordinal^ development as a result of the war. We were not travelling' via

Archangel, and devoutly thankful we were. Ammuni-’ tion ships are not liners; nor does the Arctic Ocean compare

favourably with the Mediterranean, more especially^

if you happen to get immersed in it! We were at the . moment bound for Bergen,

and were not troubling about the rest of the land journey. The first thing, in

the times we live in, .thanks to the Bosche, is to

get across the sea which girts our island. That accomplished, the rest of the

journey, whatever the destination, can be regarded with equanimity. We, born

and bred on an island, regard these crossings philosophically. But Continental

people view the matter differently. On several occasions in Petrograd, Russian

friends expressed the greatest horror of this North Sea crossing. They appeared

to be under the impression that the floor of the North Sea was paved with

German submarines who popped up as occasion demanded, bagged their ship at

leisure and retired once again to their forms. It was a pleasure to point out

that the Bosche did not find it quite so easy a

pastime as all that.

In due course we reported to the N.E.O. at the

port and an A.B. was told off to escort us to the ship, whose size, from the

landsman’s point of view, the most cursory glance showed to be far too small.

There must be many who will remember the shortcomings of this little vessel for

many years after peace once again restores the amenities of travel. But our

particular trip will remain in the memory for reasons quite apart from the

deficiencies of the little ship herself.

In conformance with the action of her Allies in

this respect, the Russian Government last summer ordered all its subjects to

either join the British Army or to return home and join up in Russia. As a

result of the order the

The men seated round the table were Russians of

more or less pure extraction—Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Poles, Czechs, Jews and

so on. One point only had all these people in common : they were one and all

wearing new boots. These new boots were significant. There would be no boots to

buy in Russia. The choice varied with the position in life of the wearer, from

the stout thick ammunition boot, through endless grades of the better-class

army .boot now procurable, to beautiful civilian boots in black, brown or

patent leather. All were being worn to avoid paying the duty. I made subsequent

acquaintance with the long boot queues in Petrograd. A lady there told me that

a maid of hers had spent all her leisure hours for a fortnight in endeavouring to buy a pair of shoes, and then gave it up.

To return to the saloon. Opposite to me sat a

gentleman of Jewish extraction, clad in a thick leather motor-jacket surmounted

by a very dirty collar, blue breeches, and good new black boots and gaiters. He

kept the whole of this kit on in spite of the stifling heat in the saloon. Hard

by a man, an artisan apparently, was clad in a suit of yellowbrown

gamekeeper’s corduroy, buttoned to the neck. He had his double, black-haired

and low-browed, similarly clothed, higher up the table. Next the former was a

member of one of the London tea-shop orchestras, with long narrow hands and

fingers, and a head of hair some six inches or more in length which had not

made acquaintance with a comb for many a day. A fourth type next to me was

obviously one of the small prosperous Russian traders who found London a good

place to live in. He was well dressed, very content with himself, and extremely

informative and boastful over his own affairs. Amongst other things he

mentioned, for the benefit of the table in general, that he had never been

short of sugar, that his small grocer, with whom he had dealt several years,

had always let him have as much as he wanted. He also entertained the company

with various other stories of a

similar nature, all illustrating the fact that we

could well do without this type of alien in our midst and let our own people occupy

their places. As a matter of fact, no country requires that type of citizen.

Another individual more difficult to place was a fine specimen of a Frenchman

of the lower bourgeois class. lie had done two years’ fighting in

France, wore several medal ribbons, and had now, so he said, got his cong& and was returning to his wife and

family in South Russia, where apparently he was settled when the war broke out.

He was an engineer by profession, and spoke English and Russian fluently and, I

gathered, several other languages. Perhaps he was a secret service man. But he

wore semi-military kit and a Russian service cap on reaching that country.

At 9 p.m. drinks became permissible on board. It

was close time at dinner. The saloon filled up and soon became reminiscent of

the Cafe Royalc in Regent Street if you add, what you

do not see there, a considerable proportion of the lower-class aliens of the

East End of London. Dominoes, chess, cards and drinks were in requisition, and

a dense pall of tobacco smoke soon filled the place, together with a babel of

tongues of all Eastern Europe. It was an interesting community to watch, but

half an hour drove me on to the confined deck space and I entered the saloon no

more that voyage. They were not exactly the class of passengers to travel

across the North Sea with, and I remained in my cabin. It was rough, and from

the reports I elicited from the cabin steward of the happenings on deck, for

most of the passengers remained on deck, being in mortal terror of Bosche submarines, I congratulated myself on this decision.

We saw no submarines. A wild panic, had we done so and been hit, was our

verdict.

CHAPTER II

TO PETROGRAD THROUGH SCANDINAVIA AND FINLAND

The

Bergen-Christiania railway is said to be the highest in Europe, and it is

certainly one of the most fascinating. Whilst? breakfasting in the restaurant

car the great climb is commenced soon after leaving Bergen, the train mounting

up by fourteen steep zigzags through beautiful pine, spruce and birch forests,

amidst which nestle the tiny neat villages, whilst deep lakes mirror the

surrounding forest. At the end of the great climb the railway runs over rocky

and stony barren fastnesses, for here we have got above tree level, still

climbing, till the highest point is reached at Fiense,

4010 feet elevation. Fiense is a tiny settlement

consisting of a handful of wooden houses amongst which the only prominent

buildings are the station and hotel alongside, a wooden-built chaletlike place, with rather an attractive timber-roofed

lounge hall. This remote village is dumped down in a howling wilderness of

rock, marsh and snow, with marshy lakes, semi-frozen even in July, in which

float great island-like masses of frozen snow and ice. In its wild austere

barrenness Fiense is exceedingly picturesque. There

are several granite obelisks here to the memory of Arctic explorers, mute

witnesses to the chief interest of the inhabitants of Fiense,

buried for three-quarters of the year in ice and snow. The latest set up is to

Captain Scott, Dr. E. A. Wilson, Captain Oates, and Seaman Evans—a tribute to

our gallant dead one liked to see. There is a good deal about this railway of

high interest, especially the way the line is protected from snowdrift and

avalanches—but better than any description I can give is an exhortation to go

and see it. You will spend the whole day amongst mountain

In my compartment there were two Norwegian

colonels and a middle-aged civilian. We had some interesting conversation. It

naturally turned on the war. I was asked for my opinion, and gave it as one

knew the position in July 1917. I naturally wanted to hear their views. In

reply to my query as to how long they thought the Germans could go on

manufacturing new big guns and the enormous amounts of munition now required,

they were dubious, but were unanimous on the point that once the limit was

reached in that production and the guns began to wear out and the shells to

fall short, the infantry would refuse to advance. No infantry in the world

would advance, was their verdict. They were exceedingly curious on the subject

of the tanks, of which they had heard fabulous stories but knew nothing

first-hand. In reply to a question about submarines, I described how the Turks

had sown the JSgean Sea with mines just before the

transport I was on had entered it the previous year. They expressed the

greatest indignation at this tale, and also commented with heat on the Germans’

submarine warfare. They expressed admiration for our great army, “ but,” said

the senior colonel, “ you were not

ready and did not listen to Roberts.” I agreed, but pointed Out that we were

not a military nation. Had never pretended to be one. Our job was on the sea

and always had been, and there we were ready. We had never undertaken to keep

up an army on the Continental scale or for Continental use. We had a crushing

burden of taxes which we paid readily to keep up the navy in peace-time. We had

not considered that our duty lay on the Continent. The colonel agreed to this.

I said that many Frenchmen whom I had met and conversed with in the past two

years admitted that they were not ready in 1914, as all the world knew. “ Nor the Russians,” he interjected. “ No,” I

replied. “ And yet both must have known of the danger. And

now in three years we have an army on the Continental scale plus the largest

navy the world has ever seen. We considered we were doing our full share and

policing the North Sea for all in addition ! ” I must say my audience listened

with the greatest attention, interpolating shrewd remarks on both the German

and Allied tactics on various occasions. We shook hands most effusively at

parting, promising to meet again after the peace. It will take several years’

journeying round the world to fulfil all the promises of this kind made since

the war started, but this last is one which I hope to make good.

Christiania was very gay and very full, but we

were only concerned to get out of it and on the next stage to Stockholm. We

were greatly struck by the pro-Ally spirit exhibited by the people generally.

The Britisher is liked here. In the book and picture shops English books and

English pictures and picture postcards with English descriptions on them were

strikingly abundant, in marked contrast to Stockholm, where they were

conspicuous only for their absence. In the Swedish capital almost every shop of

this kind had series of enlarged photographs (as also had the tobacconists)

depicting German scenes— battle pictures of Germans capturing Allied trenches;

columns of French prisoners marching between German guards; Germans behind the

lines in Belgium, the soldiers playing with Belgian children—set pieces, from

the expressions of soldiers and children, for the delectation of neutrals; or

scenes in Germany in the Unter and Thier- garten in Berlin showing

frivolous crowds parading about and enjoying themselves. The latter were

undated, so one was permitted to surmise that they had been raked out from

happier times. The people depicted were too well fed. Not all the German food

substitutes together would quite produce those expressions ! Of course our

illustrated papers show the same type of war pictures—all in our favour. No self-respecting nation can be expected to do

anything else. But we do not ask or expect neutrals to exhibit them in the shop

windows of their capitals.

The other little incident in Christiania worth

recording is the Queen of Norway’s potato patch. The Palace demesne stretches

down to one of the main streets, quite unfenced; it here consists of a stretch

of park with grass and scattered clumps of trees. An area which abutted on the

road had been ploughed up and carried a fine crop of potato plants. The Palace

head gardener, we were told, had had the temerity to demur on receiving the

order to prepare a queen’s potato patch in full view of her admiring subjects.

But the Queen was adamant and would not have it hidden, and the reluctant

servant had to obey the order. The nearest analogy to this patch in London

would be the formation of a potato patch on the region of the New Mall in the

vicinity of the Queen Victoria Statue opposite Buckingham Palace. Other loyal

subjects in Christiania had copied the Royal example—not always with like

success. In one case where the sloping lawns were heavily shaded with trees the

only result of turning them into a potato patch was the production of tall four

foot six inch straggling plants which had been dug up and thrown away by

October. Queen Maud had a heavy crop by then.

We received bad news here. Our Legation told us

that there was a strike on the Finnish railways and that we would not be able

to get to Petrograd. Also that the Russians had lost all the ground gained in

the brilliant advance brought about earlier in the month by Kerensky’s

eloquence. Things looked black, all the more so because it was impossible to

say how much was truth and how much rumour. At

Stockholm next day, however, the Finland railway crisis proved to be false. The

strike alluded to was the old one we had read of in the English papers before

we had left home. It was over. But that the Christiania Legation should not

have known this shows how slow news is in filtering through.

One of our party was an oil-company manager. He

had only just managed to escape from Bucharest with his wife and year-old child

during the retreat, had taken them to England, and was now on his way to the

Caucasus to take charge of a business there. He was enthusiastic over the

future of the oil industry in Russia, and said it was going to become one of

the most important in the world. As an indication of how the Revolution has

upset the old order in Russia, neither this man nor another of our travellers, who had been born in Russia and spent nearly

all his life there, but had been in England since the Revolution, could express

an opinion on the present position in the country; nor could they form any

estimate of the conditions they would go back to.

In Stockholm I -first made acquaintance with the

bread-card. It was at breakfast an hour after our arrival. The rather

grim-looking lady in the restaurant almost smiled when I said I had never heard

of a bread-card. Apparently I ought to have got it on the train. Some one had come round, but I must have been asleep. She

procured the bread for me. I had forgotten the incident, but it was recalled

at lunch. I had missed a companion at a place he told me to go to, and so sat

down by myself. A very pretty girl came up to take my order, and to my relief

spoke broken English. “ Bread-card.” “ No, I had none,” I blushfully

stammered as she bent down insinuatingly and asked me for it. I suppose they

are used to it, for she laughed, as did the nearest of the guests. Again the

bread was forthcoming. I don’t know how they manage it. But I provided myself

with, the indispensable card after this. These cards consist of tiny little

slips of stiff paper divided for travellers into nine

divisions lasting three days—three a day. Each one allows you one very thin

small slice of white bread, one brown ditto, and a thin longish brown rye

biscuit as hard as a brick. You can eat all your cards—I mean the bread allowed

for them —up at a sitting if you like, but you then go breadless for the rest

of the three days unless you can beg divisions from companions; the usual

procedure, this latter, I found. Sugar was as bad as at home, both in quality

and allowance. It was different in Norway, where white bread, rolls, and butter

were plentiful, as also sugar—white loaf sugar, a thing I had not seen for

months. Also the prices for food were higher in Sweden than in Norway. But

there did not appear to be any lack of money in either capital.

Had the Finnish railway been closed I had meant

to have gone on from here to Harparanda, even though

I was warned that there was no accommodation and no food, the place consisting

of a few wooden tin-roofed huts, an outcome of the war (few had ever heard of

the place before, I believe, and yet it has had the distinction of sending

forth Russian telegraphic news to an expectant world). But there is a spot near

Harparanda, an elevated tableland, from which, for a

fortnight, at about this time of the year, the sun is visible at midnight, and

I had a mind to see that if possible.

The method of feeding the passengers on the

railway when there is no restaurant car on the train is simple and effective. A

big centre table in the station restaurant is loaded

with hot and cold dishes. The passenger goes to the bar, pays the price of the

meal, receives in return the requisite number of plates, and then helps himself

and eats as much as he can or as time will permit, whichever gives out

first—the best plan I have yet met with.

I do not propose to describe the scenery, but as

an economic point of importance in after-the-war reconstruction work, and for

some considerable period with us, it is worthy of mention that although the

scenery seen passing through Norway and Sweden is chiefly interminable forests

with grand rivers and innumerable lakes, by far the bulk of the old forest in

both countries has been felled, cut up in the numerous saw-mills and sent to

the European timber markets. These latter cannot hope in the future to see for

many years to come, or only for a very short period, anything like the

quantities they have been receiving for the past half-century or so.

Sweden is a wonderfully neat country to see and

travel through. Perhaps the most interesting feature is to note the very full

use they make of their water power. In fact, the Swedes say the Americans have

copied them in this respect, and that many of the supposed American devices are

merely enlarged copies of the Swedish ones. I am unable to offer any opinion on

this head, not being an engineer. But I listened to many arguments on this

subject between an American and a Swede, both versed in engineering, on my

return journey through Sweden. All Sweden is lighted by electricity generated

from water power. And the rivers and lakes are utilised

to a high degree for floating timber and for cutting it up in the saw-mills. In

our own country in this matter of utilising water

power we can learn much from the Swedes, and it is to be hoped that when

reconstruction sets in after the war we shall not be above doing so.

The biggest town in the north is Boden, a strong

garrison town which has its counterpart on the opposite side of the Gulf of

Bothnia in Uleaborg in Finland, which is her largest

northern military cantonment. I believe the defences of

Boden have been entirely remodelled on the lines

indicated by the present war, and that it is now almost impregnable. We arrived

at Boden at 10 p.m. in broad daylight. The big unfenced station formed the

after-dinner promenade of the elite of the town, whilst the fine station

restaurant was filled with officers just finishing dinner. All the girls were

parading about in thin, flimsy white creations, and though to us from the south

the' air felt quite fresh, to them it was apparently a fine balmy night.

Harparanda

is on the Swedish side of the Tornea river at the

head of the Gulf of Bothnia, with Tornea opposite to

it on the Finnish side. The extension of the railway to Harparanda

is quite recent. Before that passengers had to detrain at Karunga

and drive up to Harparanda to cross the river; and a

rough time they had of it by all accounts in the winter. The rise of Harparanda is, it may be imagined, purely ephemeral — a

by-product of the war which will largely disappear at the peace, especially as

a big railway bridge is in process of construction here to join up the Swedish

and Finnish railway systems. The Swedes have finished their half and are now

completing the Russian section for that country. Tornea,

on the other hand, is a very ancient, curious old town of historic interest,

which would doubtless boast of tourists in peace-time were it not for its

hopeless inaccessibility, situated as it is within a score of miles or so of

the Arctic circle.

The transit from Harparanda

to Tornea was a lengthy business, taking from 6 a.m.

to 4 p.m. The Swedes were very polite and nice over the formalities, and the

business was put through expeditiously compared to the delay on the other side.

It was the waiting which took the time at Tornea, for

the Russian officials were as friendly and nice as possible. They told us that

the frontier was to be closed for several days—the time indefinite—and that we

were the last lot to be let into Russia till it was reopened. We were in luck.

Between the lengthy periods of filling in forms containing all one’s family

history for a generation or two, being interviewed, and repacking one’s kit

after it had been through the Customs people’s hands, there were some things of

interest to see. Wounded prisoners, Russian, German and Austrian, are exchanged

up here once a week. A hospital train was slowly drawing into the station at Harparanda as we left, and we met a couple of enormous

house-boat barges as we crossed the river. The men are supposed to be grands

blesses only, but it was difficult to place not a few of the Germans and

Austrians we saw in that category. The Russians had crossed the day before, and

we saw a number of them in the afternoon. They were appallingly emaciated and

thin and ill, and were, so a medical man with us said, more than half starved.

Poor devils I They were dressed in vivid- coloured

shirts of the crudest of scarlet, pink, and yellow, a distinctive hospital kit

which does not make for beauty.

Prisoners’ parcels on a considerable scale go via

this route, and to facilitate transit and lessen delay an immense overhead

wire-rope railway has been erected over the river, the length of wires being

supported on open trestle supports forty to fifty feet high. There are four

separate wires, and all day long the big bales, looking exactly like large

white flour casks, went creeping backwards and forwards over the wires. The

wires were entirely confined to presents sent by their friends to prisoners of

war. It was worth seeing and reflecting upon. Whilst on this subject of

prisoners : I had the good fortune to obtain some very interesting information

anent our own war prisoners in Germany. A young American joined my coup6 at Tornea, I having been alone so far. This American had spent

two years in Germany with the American Mission who had undertaken the work of

looking after the welfare of British prisoners. He himself worked in Wurtemburg and Baden. The Mission had a staff of fourteen

on the job and ran the business pretty much on the lines of our Y.M.C.A.,

providing games, books, etc.; getting up entertainments and supervising the

receipt and distribution of the parcels of food sent out to the prisoners. Such

contradictory accounts have been received on the subject of the treatment of

our prisoners in Germany that I naturally took such a heaven-sent opportunity

of obtaining first-hand information. I record below what he told me just as I

jotted it .down in my diary after the American had gone to sleep (the

conversation occurred after dinner), whilst we rumbled and jolted our way

through the desolate forest-clad country of North Finland. Here is the extract—

“ The American made a statement well worth recording.

He said that, on the whole, within his charge (where he was at work for two

whole years) the prisoners were well treated ancl

that with the food parcels received they had plenty to eat within his area. In

fact, he said, the prisoners did better than himself, as he was often hard put

to it to satisfy his hunger; for he was treated as a German civilian and only

got the latter’s rations. That he would have had a very poor time of it had it

not been for the British officers. The latter gave him tins of food of which,

said the American, they usually had large and often excessive supplies owing to

the great number of food parcels sent them. As to the treatment of prisoners.

He admitted that there were, of course, bad cases of ill- treatment on the part

of a commander of a prison camp who happened to be a brute by nature. Also on

the part

THE EPHEMERAL “ WAR ’’ TOWN OF

HARPARANDA, AS SEEN FROM TORNEA

![]()

RUSSIAN SOLDIERS AND SAILORS

BUYING RASPBERRIES FROM CHILDREN AT A WAYSIDE STATION IN FINLAND

of the German N.C.O.’s in striking prisoners—treating them, in fact, as if they were their own

soldiers. But on the other side, as must always be the case with armies on the

present gigantic scale, there were cases of glaring insubordination on the part

of individual prisoners which had to be treated severely, and the Germans’

ideas on the subject of treatment differ from ours a good deal.

“ This American says that he used to go into the

Germans’ military training camps, which are now placed near the prison camps,

to save soldiers required for guarding the latter. He said the German officers

were always anxious to show visitors their methods of training recruits, of

which they were very proud. Unfortunately he did not possess the military

knowledge which would have enabled him to describe them to me. He used to have

meals with them in the German officers’ casino. He told me that the military

authorities have now swept Germany clean of all men to get her last two

millions of reserves, and that so far as man-power goes she has no more at her

back. That in this last sweeping are included numbers of men who are really

incapacitated by physical infirmities —literally, as he expressed it, ‘ the

blind, the diseased, the halt and the lame ’; for partially disabled men were

included. That all these were not left in Germany, but were sent to the front

or to work behind the lines. That all sentries save the essential ones on the

prisoners’ camps have been taken off and sent to the front. Also all hospital

men orderlies, and so on. That all the office work and other work of the

country and towns is done by women, who even do sentry-go round the Palace and

public buildings in Berlin and other cities and towns. That a sentry corps had

been formed for this purpose, the women being put into uniform.

“As to food, he says the civil population are in

very low straits—find it difficult to exist, and that he himself was very run

down and low when he left Germany last April owing to America joining the war.

He said that the grain crops this year (1917) are very poor owing to the

drought, and that he himself expected a sudden collapse. Soldiers o are well

fed up at the front. The food scarcity in Germany is chiefly in the large

cities and towns, especially in the north. That in the country there is more

food, as the farmers and peasants will not sell it. The civilian population,

even in good hotels, may see a small piece of meat— about two mouthfuls, he

expressed it—once a week; for the rest weak soup of cabbage and turnip is the

staple food. The bread was the best article of food, as it is all of one

uniform quality throughout the country; only five slices a day per person were

allowed—about 3| inches in diameter (they are circular), and inch thick. The

discipline in the nation is still good, and he thought that the people liked

the Emperor and would maintain some form of the monarchy; tjiat

they wished to do so, but with a free parliament and the franchise. When war

was imminent with Germany and the American Embassy left, twelve out of the

fourteen Americans supervising the prisoners’ camps left with the Embassy

entourage. He and another man remained to instruct the neutrals, Swiss, Swedes,

and Norwegians, who were to carry on the work of supervision. The Americans wished

the work to be continued, as they had considerable funds and a large amount of

equipment and material connected with entertainments, and so forth, for the

prisoners in the country. They had found it difficult to get the class of men

required, the absolute neutral neither pro-German or pro-Ally, to take over the

job. As the American said, it is absolutely essential to have men who have no

political bias at all for this work, and he was doubtful if the world could

produce such men nowadays. He doubted whether many of the men they had been

trying would be able to carry on the job. He might have added that it will, at

any rate, be difficult to replace the efficient Americans at this juncture. His

companion had remained on when he left in April. He was treated well by the

Germans during his two years. At first all his papers were taken from him and

he was not allowed to move about; but after a time these restrictions were

removed and he was allowed to travel everywhere free of all restrictions, save

the visaing of his passport. He showed me this latter, a remarkable document,

simply black with the stamps and signatures. It was a most interesting

conversation.”

This closes the extract in my diary.

We saw plenty of the new

revolutionary soldiers and sailors en route

through Finland. They swarmed in crowds on all the station platforms. But they

were not the soldiery one associates with war-time or, in fact, with any other

time. They were merely an undisciplined mob in uniform. The Revolution has by

no means improved them, and they are very different from the fine Russian

regiments I had seen in Macedonia the previous year. There are now four types : (1) The swaggering loafer

who cares for nothing but a full stomach, plenty

of cigarettes, no drills (and, of course, no fighting), and to be allowed to

have his own way. (2) The dull-faced, totally illiterate man who has only as

yet grasped one thing— that

he is to have plenty to eat, to do no drills, and not to salute or pay any

attention to his officers, but must still obey the Soldiers’ Committees and

vote as they tell him to on any question. He understands nothing of the present

situation, but obeys the Committees so long as there is no chance of his being

sent up to the front— he is in the

majority. (3) The sullen, obstinate, strong- minded ultra-Socialist who is the

leader of the Soldiers’ Committees and the mainstay of the Council of Workmen

and Soldiers. He is the dangerous man of the present time, purposely rude and

threatening to all officers and bourgeoisie, as all who are educated and

wear a black coat are termed, and out to get his rights, i.

e. equality for all, equal division of property, and he to rule the new

country and be obeyed in everything. (4) There is a fourth class— a small minority—the

old type of Russian soldier (it is said it is less abundant in the navy),

courteous and deferential and polite to all he has always recognised

as his superiors. He exists in the cavalry and artillery, who have mostly

remained loyal to the Provisional Government and Russia, and to a far lesser

extent in the infantry.

Two examples of the new state of affairs struck

us as we left Tornea for the south. A Russian troop

train had come up north and was standing at a siding, the wagons decorated with

branches, etc., the men happy at having got so far from the front. A Russian

officer in our train thus addressed three of the men who were walking between

the trains : “ Heh, my friends ! Where are you going to, colleagues ? ” One of

the men turned his head and curtly replied without halting or saluting,

speaking not even as to an equal, but as if he considered the officer an

inferior— as he probably did. The second incident occurred in the evening in

the first-class restaurant car. Two Russian privates lurched in, sat down in

two of the places, and proceeded to eat the same dinner as we had, partaking of

it mostly with their fingers; they were in a line with my companion and myself

across the alley-way, and made horrible noises. At the end* of the meal one of

them produced a Finnish hundred-mark note and tossed it to the attendant. I

was told that a month or two ago they would not even have paid the bill. But

they have plenty of money nowadays, and can get more when they want it— those

who are of use to the Soldiers’ Council. And the Russian private now gets seven

and a half roubles a week instead of eighty copecks

as heretofore ! Think of an army computed at twelve million men paid at fifteen

shillings a week—and that in Russia !

Finland is chiefly a forest country, a poor duplicate

of Sweden. The climate is too rigorous and the soil too poor to ever make

agriculture a paying business. The class of arable land seen and the type of

crop, including the miserable little hay crops they were garnering in July, was

a matter of surprise to any one accustomed to the

crops reaped in more equable climates and on more highly productive soils. The

forests, though not of the same class as the Swedish ones, in the northern half

of the country at any rate, are valuable and will have an increasing value. In

fact, the country will be likely to obtain a fair if not large income from this

source in the future. Lakes and water power are as plentiful as in Sweden, if

not more so.

We reached the frontier between Finland and Russia

at 11 p.m., and after an hour and a half of formalities here finally arrived at

Petrograd at 1 a.m. All the prophesies that there would be no droskies and that

if there were any they would demand forty roubles to

take us to our hotels were falsified. There were lots of these pirates of the

Petrograd streets, and I secured one for the drive to the Hotel Europe at a

moderate figure. The capital was quiet and wrapped in slumber, and showed no

evidence of its past few months of excitement.

CHAPTER III

RUSSIA AFTER THE REVOLUTION (APRIL—JULY)

R&SUMti OF CHIEF

EVENTS------- RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE ON

THE

SOUTH-WESTERN FRONT

A brief r£sum6

of the chief events which took place during the three months following the

Revolution is a necessary preliminary to a narrative dealing with the period

which ended with the fall of the Provisional Government in November 1917, and

the seizure of the supreme power by the Bolsheviks under Lenin and Trotsky. The

Czar abdicated on March 15th, the Duma then becoming the controlling authority

of the country. The Duma, whose members mainly consisted of the bourgeoisie,

set up the first Provisional Government, a Cabinet of Ministers, who then

became the legal governing authority. But they quickly found a rival in the

Council of Workmen and Soldiers who represented the Socialists. This body had

grown out of the Petrograd Council of Labour first

formed during the Revolution of 1905. In the early days of the March Revolution

some of the socialistic workers in Petrograd revived this Council, and in order

to give it added strength brought soldiers into it, the body thus constituted

styling itself the Council (Soviet) of Workmen and Soldiers. This Council very

soon claimed all the honour of having made the

Revolution, and from the first, although it was not at once recognised,

dominated the Provisional Government. The Prime Minister of the latter was

Prince Lvoff, who held the portfolio of the Interior.

The other Ministers were Miliu- koff,

Foreign Affairs; Shingareff, Agriculture; Gutchkoff, War; Tereshchenko, Finance; and Kerensky,

Justice, the latter a Socialist and vice-president of the Council of 22

RUSSIA AFTER THE REVOLUTION 23 Workmen and

Soldiers. The president of the latter body was Tchkheidze,

a man of considerable personality, and one destined to play a leading part in

the months to come. The Council had at their back from tlie

beginning the labour classes and peasantry. Within a

few months they secured the support of masses of the troops in the rear.

The Provisional Government initiated radical

changes in the administration of the country. Decrees granted full amnesty to

all political prisoners, removed all the Romanoffs,

and those known to favour them, from official posts,

issued a Manifesto completely restoring the Constitution of Finland, emancipated

the Jews, and addressed a rescript to the Poles stating that Russia regarded an

independent Polish State as a pledge of a durable peace. The Government then

abolished the death penalty, one of the steps which were ultimately to cause

its downfall and led to untold misery in Russia. The Government declared itself

in favour of Woman Suffrage, and agreed to the

suggestion that all the land should be distributed amongst the peasants. But

the method of distribution they left to the Constituent Assembly, a body which

was to be elected by universal suffrage and which would ultimately decide the

form of the Government of the country. International problems, questions of

nationality rights, so soon to assume a formidable place in Russian politics,

agrarian and labour legislation, and the abolition of

titles, classes, etc., were also to be left for the decision of the Constituent

Assembly. The origin of the Council of Workmen and Soldiers in Petrograd has

been described. Similar councils were formed throughout the towns of the

country, and these soon arrogated to themselves the positions of the Zemstvos

Committees which had done such excellent work during the war. Throughout the

country the old police were replaced by a militia, an inefficient force of very

little use for the most part.

A later step taken by the Provisional Government

was the issue of the “ Soldiers’ Charter.” This charter was drawn up with a

view to removing many of the gross abuses of power which existed in the army

under the Czar, and with a view to democratising the

army. But it went too far. This charter was not the work of Gutchkoff,

first War Minister. Finding, even in these early days, that it was impossible

to work with the Council of Workmen and Soldiers, he had resigned, as had Miliukoff for the same reason, though a different cause.

Kerensky was now War Minister, and issued the charter. Under its provisions the

soldiery were accorded equal citizens rights, freedom

in religion and speech, equal freedom with other citizens in matters relating

to correspondence and receipt of printed matter (subsequently taken full

advantage of by the German propagandist), permission to wear civilian dress off

duty, abolition of servile terms in addressing officers, abolition of saluting

officers or serving them as orderlies, and abolition of corporal punishment.

To the issue of this charter, the abolition of

the death penalty, both the work of the Provisional Government, and the famous Prikaz (Order of the Day) No. 1, published by the Council

of Workmen and Soldiers, which resulted in the formation of the Soldiers’

Committees, must be attributed the subsequent break up and ruin of the Russian

Army. The Prikaz was the first of the three to be

issued, and its history is as follows: Whilst the Revolution was in progress

the allegiance of the soldiers was made to the Duma, which assumed the

authority laid down by the Czar. These soldiers included some of the most

famous of the Russian regiments, as also the Cossacks. The Duma had in its

ranks many of the ablest men in Russia, but they did not act with the

promptitude and firmness the times required. One of the first acts taken by

some of the Bolshevik military members of the Council, immediately after the

triumph and whilst the nation was intoxicated with its newfound freedom, was

the issue of Prikaz No. 1, which practically resulted

in the abolishment of discipline in the army. The draft of the Prikaz was carried by some soldiers to the President of the

Military Commission of the Duma, who refused to accept or issue it, a

decision*m which he was supported by the Provisional Committee of -

RUSSIA

AFTER THE REVOLUTION 25

the Duma. This was on March 14th. “ Very well,”

said the soldier delegates, “ we will issue it ourselves.” It appeared the

following day. The main provisions of the Prikaz were

the election of the subaltern officers by the soldiers themselves, retention of

their arms by the soldiers, and the superintendence by Soldier-Committees of

the administration of their own units. In practice it put the private on an

equality with his officer, whom he addressed as tvaritch

(comrade). In times of peace this must have bred trouble. With the nation at

war and the subversal of discipline which followed,

its consequences have been incalculable.

The political parties in Russia are subdivided as

in other countries, and these subdivisions have led to curious misconceptions

amongst foreigners as to their aims and objects. It must also be admitted that

the opinions of the subdivisions underwent some considerable modifications or

the reverse as time w’ent on. Generally speaking, the

Cadet or Constitutional Democratic party consisted of the intellectual classes,

the bourgeoisie. With the exception of the socialist Kerensky they

formed the first Provisional Government. This party contains a large number of

very able men, and before the Revolution they were aiming at a Constitutional

Monarchy, and for a short time subsequent to the upheaval. But at a Congress

held early in April the delegates voted unanimously for a Democratic and

Parliamentary Republic. The Socialists consisted of two main groups, Social

Democrats and Socialist revolutionaries. The chief aim of the first was to

ensure that labour should dominate capital; of the

second to secure the land for the peasants. Both these groups were, however,

subdivided within themselves. The Social Democrats consisted chiefly of

Bolsheviks with a smaller Menshevik group. The Social Revolutionaries were

subdivided into Maximalists and Minimalists. The ranks of the Maximalists

included the Anarchists and Terrorists of the old regime. Many of these had

been bribed by the old police to enter the Terrorist party in order to act as

spies on it. These men still remained, and were a grave menace to the country,

since their old source of income was gone. As the Bolsheviks also believed in

violence, the Bolsheviks and Maximalists formed an alliance. It is known that

many of the old Terrorists were Jews, clever unscrupulous men who made a

profession of this business. They were now in power in the Petrograd Soviet or

Council, bearing Russian names. The best known to foreigners are Lenin

(real name Zederblum), Trotsky

(Bronstein), Tchernoff (Feldmann), Parvies '(Helfand), Bogdanoff (Seffer), Martoff (Zederbaum), Kameneff (Rosenfeld),

Goreff (Goldmann), Sukhanoff (Himmer), Stekloff (Nahamkes), the latter

the reputed author of Prikaz No. 1, and so forth. The

Mensheviks, with Tchkheidze and Tseretelli

at their head, with the Minimalists (under Kerensky), wished to allow the Duma

to govern the country until they felt they had sufficient backing to dominate

the Provisional Government and perhaps seize the power. The Bolsheviks and

Maximalists, on the other hand, wished to push through their creed early and by

force, and with this object they systematically set to work to wreck the army,

the one power they feared as long as it retained its discipline. In this they

were immensely helped by the horde of German spies and by German gold, both of

which were placed plentifully at their disposal.

It was the fight against the rot setting in in

the army in the rear that first brought General Korniloff,

the Cossack General who escaped whilst a prisoner in Austria, into notice, he

having been appointed to the command of the Petrograd military district. After

carrying on this unequal struggle for a time, he asked to be relieved and given

a command in the field.

One of the administrative pieces of work which

occupied the attention of the first Cabinet was the question of the finances of

the country. It was realised that Russia could only

be financially rehabilitated by developing her great resources, and to this end

they wished to invite foreign capital into the country. In this they were

opposed by the Socialists, who did not believe in economic expansion.

KERENSKY CARRYING THE FIERY CROSS ROUND THE FRONT

IN JUNE, I917

KERENSKY ADDRESSING THE TROOPS AT THE FRONT IN

JUNE, 1917

KERENSKY IN THE TRENCHES IN JUNE, I917

Miliukoff’s

resignation came about through a difference of this kind. He had advocated the

annexation of Constantinople as an economic necessity for Russia. The

Socialists were against all annexations, and the Council of Workmen and

Soldiers at once protested. The Prime Minister explained that Miliukoff’s statement was only an exposition of his own

views on the matter—not those of the Government. But the Government were forced

by the agitation set on foot to issue a declaration denouncing all aims towards

annexations and war indemnities. This step was taken to save the Cabinet, but

it was taken unwillingly. Miliukoff sent this

declaration of the Cabinet to the Allies with a note : “It is understood, and

the annexed document expressly states, that the Provisional Government, in

safeguarding the rights acquired for our country, will maintain a strict regard

for its engagements with the Allies of Russia.” This note gave rise to an

outburst from the Socialists, aided by the German spies who were swarming in the

capital. The Bolsheviks led this campaign, headed by Lenin, who had recently

arrived at Petrograd from Switzerland via Germany. Lenin went too far, and was

not supported in his pacifist campaign by the Council of Workmen and Soldiers.

The aim and hope of this body was in effect a revolution amongst the workers of

Europe, with the object of overthrowing all the European Governments and secret

diplomacy and governing through the masses. The policy of conquest was to be

suppressed, but they would fight to save their own country from invasion. To

this end they appealed confidently to the workers in the enemy States to rise

and overthrow their rulers. A crisis supervened, and Miliukoff

resigned.

A national Congress of the Councils of Workmen

and Soldiers from all over the country followed shortly after the Cadet

Congress. At this Congress the policy of maintaining a firm control over the

actions of the* Provisional Government was definitely announced, in order to

prevent it from siding with the counter-revolutionary forces, and to assist the

Government in obtaining a peace based on a free national development for all

peoples and without annexations or indemnities. The Congress appealed to the

whole revolutionary democracy to rally round the Council and to support the

Provisional Government, so long as its foreign policy was free from all desires

for territorial expansion and provided that it maintained the Revolution. The

democracy was also asked to aid the Council in preventing the Government from endeavouring to weaken the control of the democracy, or

renouncing any of the pledges made to it.

The actions of the Soviet had not left the army

rm- touched. The pernicious influence of the committees and propagandists had a

startling effect on the previously well-disciplined masses of soldiery at the

front, whilst the rear degenerated even more rapidly. At the front the creed of

no annexations and no indemnities naturally left the soldiers wondering what

they were fighting for. The Germans, after breaking the Russian lines on the Stokhod with ease, ceased fighting and commenced fraternising instead, an occupation they steadily pursued

for some time. General Alexeieff, who had been

appointed Commander-in-Chief after the Revolution, worked hard but without

success to stem this deplorable tide.

After the Government’s declaration of no

annexations, etc., the Council of Workmen and Soldiers stated that their policy

of no annexations had now become an international question and that democracy

had thereby scored a great victory. It was, however, as it turned out, a great

blow at the efficiency of the army.

Gutchkoff

followed Miliukoff into retirement, and the first

non-socialistic Government gave place to a coalition containing several

Socialists. Lvoff remained Premier; Kerensky became

Minister of War and Marine instead of Justice; Tereshchenko, Foreign Affairs insfead of Finance; Shir- gareff,

Finance instead of Agriculture ; and Konovaloff,

Commerce and Industry. Five Socialists entered the Ministry. Tchernoff, Agriculture; Skobeleff,

;Labour; Tseretelli, Posts and Telegraphs; Pereverzeff,

Justice; and Peshekhonoff, Munitions. The Duma

appeared officially for the last time at a Conference which preceded the formation of this Cabinet. From now onwards it disappeared

before the socialistic advance. The soldier’s charter was Kerensky’s first act

in his new position. It had effects which may or may not have been anticipated.

Generals Alexeieff and the Commander of the Central

Front, Gurko, resigned (the latter being then degraded

by Kerensky), Brusiloff taking the former’s place,

and the veteran Ruzsky was dismissed from the Command

of the Northern Front. It appeared as if the army would then and there crumble

to pieces. But Kerensky now took a step which had extraordinary results. He

went round the front with a fiery cross and an intense enthusiasm, his great

oratorical gift assuring him a hearing wherever he went. Though he himself

deplored the fact, when some one asked him whether he

imagined that all his soldier audiences could understand him, that probably not

more than one man in a hundred could so do. This fact mattered little for the

moment, however, as the enthusiasm his mere appearance aroused was contagious.

He preached an offensive, and the last brilliant and meteoric advance of the

Russian Army came off. But in acting in this fashion, Kerensky, who ever placed his country above his socialism, was far

from carrying out the wishes of the Workmen and Soldiers’ Council. Tchemoff, speaking to delegates from the front, actually

said : “A peace must be concluded in which there shall be no victors and no

vanquished. Appeals have been published for an immediate attack, but the army

should take advantage of the present calm, at the front to organise

itself, and then it will not need any prompting, as it will know itself what to

do.” At this juncture the Cadet Minister of Commerce, Konovaloff,

declaring that the class war being fomented by Tchemoff

and Skobeleff would result in a catastrophe,

resigned. But even the Soviet was carried away by the general enthusiasm when

the advance of the armies commenced.

The bait by which the Council

attracted the workmen to their support was a six hours’ day and constant

increases in wages; that for the peasants was the division of all land amongst

them, of which Tchemoff was the chief exponent.

During the period under review the Moderate Socialists joined with the

Bolsheviks in debauching the three classes of the masses—the soldiers, workmen, and peasants. It was not

till much later that the Moderates, realising the

peril the country had been placed in, split definitely with the Bolsheviks—and then it was too late.

The Ukrainian question, the first of the

nationality questions which were to result in, it is to be hoped, a temporary

dismemberment of the Russian Empire, now came into view. Soon after the

Revolution a Council, or Central Rada as it was called, was formed at Kieff which said it spoke for the Ukrainian nation. It

decided to call a Constituent Assembly into being in order to settle a form of

government for the Ukrainians. The local Socialists were alarmed at this move,

but were told that the Provisional Government had sanctioned it. Soon after a

Congress of Representatives voted for autonomy in a federal Russian Republic,

and the area to be governed by the Ukrainians was extended to Poltava, Kharkoff and Odessa. Kerensky visited Kieff,

and promised that if they would wait till the Constituent Assembly met most of

their wishes would be granted. But the Rada asked for more than this promise, and

a Congress of soldiers and peasants sitting at Kieff

voted for far more than the Rada was asking for. The Provisional Government endeavoured to compromise with the Rada, the Council of