PREFACE

I must begin by telling my

readers that this book is only partially my own. The inspiration to undertake

it and a portion of the material it contains were derived from an unfinished

life of Suleiman the Magnificent which was written by my beloved friend, the

late Archibald Cary Coolidge in 1901-02. He and I discussed it constantly during

the next five years, and I frequently urged him to complete and publish it; but

other things intervened, and when he died in 1928 the manuscript was deposited

in the Harvard Archives just as he had left it twenty-six years before. There,

some twenty months ago, I found it, with the words “For R. B. Merriman” written

in his secretary's hand on the fly leaf; and this I took as a summons to put it

in shape for publication. My first intention was to leave as much as possible

of his work untouched, write the three chapters which had been left undone, and

edit the book under his name; but this plan did not prove practicable. So

instead I have rewritten it ab initio, and made a number of changes in the

original form. I hasten, however, to add that a considerable portion of Chapter

I and scattering paragraphs and sentences in Chapters II-VI and IX—XI have been

taken, with some revision, from Professor Coolidge's manuscript. Chapters VII,

VIII, and XII are wholly my own.

No apology is offered for the

fact that the following pages are chiefly a story of diplomacy and campaigns.

Military considerations invariably came first in the Ottoman mind, and Suleiman

was primarily a conqueror. Professor Coolidge's unfinished manuscript is even

more of what has been called a drum and a trumpet history” than is this book,

but I am glad to take this opportunity to testify to my unshaken belief in the

doctrine which he constantly preached—namely that a knowledge of the narrative

is the indispensable foundation for everything else.

Constitutional, economic,

social, psychological, and all the other various “aspects” of history which

have been successively labeled with capital letters, and have temporarily, each

in turn, held the center of the stage in recent years, are perfectly

meaningless without it. Moreover they are none of them really new, as their

chief proponents would have us believe; they have all been studied —without

their modern titles— ever since the time of Herodotus.

I trust that the publication

of this life of one of the greatest yet least known sovereigns of the sixteenth

century will serve among other things to remind Harvard men all over the world

of the immense debt which the University owes to Professor Coolidge. To one

who, like myself, has studied and taught here for over half a century, that

debt looms larger and larger as the years go by. Others have already written of

his unfailing kindness, humor, and tact, of his boundless generosity and

unselfishness. Here, however, I want especially to emphasize the greatness of

his achievement in broadening the University's horizon. The Widener Library and

the collections which he gave or obtained for it are perhaps the most

conspicuous monument to his success in this respect; but the Corporation

records and the University Catalogues of the last fifty years tell a no less

notable tale for the curriculum. When Professor Coolidge came back to Harvard

in 1893, the only undergraduate instruction given in modern history outside of

the United States consisted of two general courses on Western Europe in the

seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries; the Scandinavian, Slavic,

Ottoman, and Iberian worlds were left practically untouched; the African,

Asiatic, and Latin-American ones wholly so. Two years later we find Professor

Coolidge himself offering two half courses, to be given in alternate years, on

the history of the Scandinavian lands and on the Eastern Question, and in

1904-5 another on the Expansion of Europe since 1815. In 1896 he persuaded the

Corporation to embark on an even more daring adventure, and invite “Mr.” (later

Professor) Leo Wiener to give instruction in Slavic Languages and Literature,

with the understanding that he was also to assist at the Library in cataloguing

Slavic and Sanskrit books; and in 1907-08 Professor Coolidge himself offered a

full course on the history of Russia. All this was the entering wedge for

greater things to come, not only at Harvard but elsewhere; it deserves, in

fact, to be regarded as the origin of the scientific study of Slavic history,

languages, and literatures in America. A half course in Spanish history was

first given in 1903, and a professorship of Latin-American history and

economics was endowed a decade later. Instruction in the history of Asia and of

the African colonies was to follow in the succeeding years. For every one of

these and for many other advances, Professor Coolidge was directly or

indirectly responsible. Invariably he foresaw and pointed out the need. Often

he gave generously to meet it, and his judgment of men was sound and keen. It

has been well said of him that he was far more interested in the production of

scholars than in the products of scholarship itself. To him more than to any

other man is due what the Harvard History Department was able to accomplish in

the days of its greatness. To us who have been brought to open our eyes to

wider horizons by the tragic events of the past five years, his visions of a

half-century ago seem prophetic.

When one leaves the familiar

shores of Western Europe and ventures out into the Levant, one needs the safest

and wisest of pilots, and I have been fortunate in finding them. The names of

two friends—Professor A. H. Lybyer of the University of Illinois, and Professor

R. P. Blake of Harvard—stand at the head of the list. The one has gone through

my galleys and the other my manuscript with the most assiduous care, and both

have saved me from countless errors and told me much I did not know. Rev. J. K.

Birge, Chairman of the Publication Department of the Near East Mission of the

American Board, has generously placed his intimate knowledge of Turkish and

modem Turkey at my disposal. Dr. Erwin Raicz, of the Harvard Institute of

Geographical Exploration, has drawn the map, and incidentally taught me much

about the Danube campaigns. Such accuracy as the note on the portraits of

Suleiman may be found to possess is chiefly due to the liberal help of Dr. A.

Weinberger of the Houghton Library at Harvard, of Mr. W. G. Constable of the

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and of Miss Agnes Mongan and Miss Margaret Gilman

of the Fogg Art Museum; and the officials of the Harvard and Yale University

Libraries have facilitated my researches in many different ways. Mr. G. W.

Robinson has given me all sorts of precious, aid —as he has with other volumes,

during the past thirty years and more. My wife has been my sympathetic critic,

collaborator, and companion from first to last; without her constant

encouragement this book would never have been finished.

R. B. M.

Cambridge, Massachusetts

September, 1944

CONTENTS

EARLY HISTORY OF THE OTTOMAN

TURKS

YOUTH AND ACCESSION OF

SULEIMAN. CONTEMPORANEOUS EUROPE

BELGRADE AND RHODES

MOHACS

THE SIEGE OF VIENNA AND ITS

AFTERMATH

RELATIONS WITH FRANCE TO 1536

THE GOVERNMENT

THE SERAGLIO; THE HAREM; THE

SULTAN AND HIS SUBJECTS

WAR AND VICTORIES IN THE

MEDITERRANEAN; KHAIREDDIN BARBAROSSA

PERSIA, INDIA, AND ABYSSINIA

HUNGARY AGAIN: 1533-1564

MALTA AND SZIGET. DEATH

Early History of the Ottoman Turks

Few periods in history

possess such fascination as the first half of the sixteenth century. All over

Western Europe the spirit of the Renaissance had triumphed, and was wakening

the human mind to ever greater activity. It was a golden age of art, of letters,

and of science: an age of daring exploration and adventure, of passionate

religious emotion and controversy. The discoveries of da Gama and Columbus had

opened up new worlds to European enterprise; the teachings of Luther and his

successors rent hopelessly in twain the Western Church of the Middle Ages. It

was also an epoch of decisive moment in the growth of nations. Italy became at

once the intellectual guide and the political prey of ruder and stronger

powers. The Holy Roman Empire of the German people, though internally more

disrupted than ever, was officially headed by the mighty House of Hapsburg, the

marvellous success of whose marriage policy had already won it the lordship of

the Netherlands and the kingship of the Iberian realms, and promised the speedy

realization of its traditional aim: Austriae

est imperare orbi universo. France and England, consolidated under the

strong rule of the Valois and the Tudors, were full of youthful life and energy

and eager too, while Spain in a few short years acquired the largest empire on

the globe. In this age of intense activity the leading figures stand out with

unprecedented clearness. The spirit of the Renaissance was above all

individualistic, and at no time in the annals of mankind do we find a greater number

of outstanding personalities in the political as well as in the religious and

artistic world. The Spain, the France, and the England of that day at once

recall the names of Charles V, Francis I, and Henry VIII: all men of mark, who

played no small part in making history, and well deserve the study and

scholarship that have been lavished on them.

Modern historians, however,

have devoted singularly little attention to one meriting it equally well, the

fourth great sovereign of the time, Suleiman “the Magnificent”, “the Great”,

“the Lawgiver” —the ruler of the Ottoman Empire at the height of its glory and

strength, a conqueror of many lands, whose fleets dominated the Mediterranean

and whose armies laid siege to Vienna, whom Francis I of France addressed as a

suppliant, and to whom Charles V's younger brother Ferdinand paid tribute. A

great English historian has justly observed that “the thrones of Europe were

now filled by the strongest men who ever contemporaneously occupied them. There

may have been greater sovereigns than Charles, Henry, Francis, and Solyman, but

there were never so many great ones together, of so well-consolidated dominion,

so great ability, or so long tenure of power.” Of that remarkable quartet the

Turkish Sultan was assuredly not the least. In the politics of Western Europe

his influence was profound, for he played a more decisive part in the struggle

between Charles V and Francis I than did Henry VIII of England, and the danger

of a Turkish invasion of Germany continually affected the course of the

Protestant Reformation. The history and character of Suleiman are also of

lively interest in themselves. He was the last and perhaps the greatest of that

extraordinary series of able rulers who built up the Ottoman state from a

little vassal principality into a mighty empire, and made it the terror of

Christendom. He was equally noteworthy as a warrior and a statesman, and his

private character, though stained by a few acts that even his inherited

surroundings and traditions cannot excuse, was yet such as to command the

admiration of his enemies. But, before attempting to portray him, we must

devote the rest of this chapter to a hasty sketch of his predecessors, who made

his reign possible. No other line in all history can show such a long and

almost uninterrupted succession of really remarkable men.

In the middle of the

thirteenth century events of high importance were taking place both in the

Christian and in the Mohammedan worlds. The death of the Emperor Frederick II

(“Stupor Mundi”) on December 13, 1250, marked the end of the greatness of the

mediaeval Empire. The Latin Empire of the East, the chance foundation (1204) of

misdirected crusaders, was nearing the close of its short and inglorious span

of life; in 1261 Constantinople was recaptured by the Greeks. Russia had just

fallen under the terrible yoke of the Mongols, who delayed for centuries her

participation in the affairs of Western Europe. England was becoming

increasingly restless under the misgovernment of Henry III. In the Mediterranean

lands the conflict between Cross and Crescent still continued with varying

fortunes. In the Iberian Peninsula the tide had definitely turned in favor of

the former, and the Moors had lost all their possessions save the little realm

of Granada. But farther east the Christian kingdom of Jerusalem had been almost

obliterated, and St. Louis had been defeated and made prisoner at Mansurah in

Egypt, where internal troubles led shortly afterward to the establishment of

the first Mameluke dynasty. It was at this juncture, when Western Asia was

already threatened by the Mongol attack soon destined to overwhelm Baghdad and

put an end to the Abbasside Caliphate, that, according to a more or less

credible tale, a wandering adventurer from the eastward, at the head of a small

following, plunged into a battle that was being fought on the Anatolian

plateau.

This unexpected combatant was

a warrior named Ertoghrul, and he belonged to another tribe of the same race as

the Seljuk Turks, who had defeated the East Roman Emperor at the battle of

Manzikert in 1071, and subsequently overran the whole interior of Asia Minor.

Broadly speaking, the name Turk (Turcae), which we find in the classical

writers of the early Christian era, may be used to designate that section of

the Finno-Ugric inhabitants of the great steppes of Asia which was the more

Western and Caucasian in its affiliations; while the other, which looked

towards China, is called Mongol. These tribesmen had no race prejudices: they

had mingled freely from the earliest times with their white neighbors on the

West, and their yellow ones to the eastward; “the Turkish peoples(for the

Western world) are then in general those Tatars who have had the greatest

admixture of Caucasian blood”. They were divided into many tribes, of which few

save the Seljuks had yet reached a stage much more advanced than the nomadic;

the small band led by Ertoghrul formed the remnants of one of the lesser of

them. It would appear that he did not even know the names of the combatants in

the battle which he had joined, but he was chivalrous enough to take the weaker

side. It was only after victory had been won by his aid that he learned that he

had assisted Kay-Kubad, the Seljuk Turkish Sultan of Rum (or Iconium), against

a Mongol army. The Sultan, in gratitude, took his preserver into his employ;

and subsequently, in return for further service, rewarded him with a grant of

land around the present town of Sugut. This territory is situated in Western

Asia Minor, not far from the cities of Isnik and Ismid, formerly Nicaea and

Nicomedia.

We know but little of

Ertoghrul, although legend has been very busy with his name. At his death in

1288 he was succeeded by his son Osman, about whom we have more definite

information. At first the new ruler continued to play the role of the faithful

vassal of the Sultan of Rum; he aided his master against further Mongol

attacks, and obtained fresh favors in return for his devotion. But he was also

constantly occupied in warfare with the semi-independent commanders of the

Greek frontier posts—a warfare of foragings and skirmishes for plunder as much

as for conquest, which gradually increased his territory and his prestige. In

the course of this warfare Osman, the future greatness of whose empire is

supposed to have been foretold him by a marvellous dream, is said to have

become a Mohammedan. If the tale be true, he could thenceforth regard himself,

not as a mere freebooter and ambitious chief, striving only to add to his own

territories, but as a champion of Islam, whose cause was sacred in the eyes of

all true Moslems.

Meanwhile many changes were

taking place among the great powers of the East. The Mongols had at last met

their match in the Egyptian Mamelukes; their progress had been checked, and

their dominion was breaking up; but they still remained formidable to the

Turks. By the close of the thirteenth century they had put an end to the Seljuk

empire. Out of its fragments were formed upwards of a score of email

independent Turkish principalities, which for the most part took their names

from their rulers. That of Osman (or “the Ottoman” as we call it) was neither

the largest nor the most powerful, but it was so close to Christian territory

as to offer all the temporal and spiritual advantages of a war for the faith, and

Moslem recruits from all Asia Minor were speedily attracted thither. In the

following years Osman's attacks on his enemies redoubled. It is true that his

force, chiefly composed of light cavalry, could at first do little against the

walls of the Greek cities, but the fact that those cities were left to fend for

themselves by the government of Constantinople was ominous for the future.

After the reconquest of its capital in 1261, the energy of the Byzantine Empire

seemed to slacken. What remained was used up in internal disputes, in conflicts

with Venetians and Catalans, with Servians and Bulgarians, and with Turkish

pirates in the Mediterranean. The cities of Asia Minor were given no help; year

after year their power of resistance weakened, as the Ottoman bands laid waste

the open country, and cut off supplies and communication with the outside

world. Ten years of this sort of blockading brought the city of Brusa into

Osman’s hands in 1326; but the news of the triumph only reached him on his

deathbed. He died as he had lived, in the simplicity of a nomad chief, leaving

as his sole personal possessions, besides his horses and sheep, one embroidered

gown, one turban, one saltcellar, one spoon, and a few pieces of red muslin.

He had designated as his

successor, not his studious and peaceable elder son, but his younger one,

Orkhan, who took the title of “Emir.” Already distinguished as a warrior on

more than one occasion, Orkhan now continued in the same path. Before long

Nicaea and Nicomedia had fallen into his hands; he also increased his

territories at the expense of Karasi, one of the other Turkish principalities.

Then followed a peace of twenty years, during which he governed wisely and

well, and consolidated the institutions he had already established; indeed, it

is rather as an administrator than as a conqueror that Orkhan is famous in

Turkish history. Aided by his older brother and vizir, Ala-ed-Din, and by other

counsellors, he introduced the first Ottoman coinage, regulated the costume of

his subjects, divided up his territory into provinces, and above all

reorganized his army. Hitherto the Turkish troops had consisted of the ordinary

levies of feudal cavalry, who served in return for land and plunder. By the

creation of the famous corps of the Janissaries, Orkhan obtained at little cost

a body of highly disciplined regular infantry, thus strengthening his army in

precisely the element in which Asiatics have almost always been weakest in

comparison with Europeans. He also instituted a force of regular cavalry; in

fact, he may be justly said to have established the nucleus of a national

standing army at least a century earlier than any of the Christian sovereigns

of the West.

In 1346 Orkhan had taken to

wife a daughter of the Byzantine emperor, John Cantacuzenus, with whom he

henceforth remained on friendly terms. This, however, did not prevent him from

continually attempting, by one means or another, to get a foothold in the

European dominions of his father-in-law. At last, in 1357, his oldest son

Suleiman crossed the Hellespont by night with a few companions on two rafts,

and seized the ruined castle of Tzympe. Reinforcement's soon followed, in spite

of the remonstrances of the Emperor; and an earthquake, which threw down the

walls of the city of Gallipoli, gave the newcomers an invaluable base for

further operations. Even the death of Suleiman, which was followed shortly

afterwards by that of his father, only served to clear the way for a new

leader.

The next Emir, Murad I, was

forty-one years old at the time of his accession in 1359, and a truly

remarkable man. Primarily a soldier of Islam, stem, severe, and recklessly

brave, with a tremendous voice which thundered over the battlefield, he was

also a great builder of mosques, of almshouses, and of schools. And yet he

could neither read nor write. When his signature was needed, he dipped his

thumb and three fingers in the ink, and applied them — well separated— to the

paper; a popular legend tells us that this mark was used to form the basic

pattern of the “tughras” or calligraphic emblems of subsequent Ottoman rulers.

Murad came to the throne at a most fortunate moment. Not only did he inherit a

reorganized army—full of religious and warlike ardor and led by brilliant

officers; the political situation in southeastern Europe was also highly

favorable to his designs. The death in 1355 of Stephen Dushan, the greatest of

the Serbian princes, had deprived the petty Balkan states of the one leader who

might have been able permanently to check the Turkish advance. Only two enemies

were really to be feared. The warlike kingdom of Hungary —then nearing the

height of its power under Louis the Great of the House of Anjou— was, on paper

at least, a formidable antagonist; but Louis was too much occupied with the

affairs of the West, and especially Poland, to devote due attention to the

danger to the Balkans from Asia Minor; and the religious differences between

his Roman Catholic Hungarian and Orthodox Slavic subjects made it well-nigh

impossible for them effectively to combine. In the republic of Venice the Turks

had another even more dangerous potential foe. The wealth and resources of the

city of the lagoons, her daring commanders and her skillful diplomats, her

splendid fleet and her many strategic possessions in the Levant made her a

power not lightly to be reckoned with; but for the time being she was much more

concerned with her struggle against her commercial rivals the Genoese than with

the protection of her territories in the Balkans. Her fleets might harass the

Turkish seacoasts and cut off communications, but they could not check the

advance of the Ottoman armies.

Murad did not long leave the

world in doubt about his intentions. His forces marched suddenly to the

northwest and captured Adrianople, which from 1366 till 1453 remained the

European capital of the Turks, corresponding to Brusa in Asia Minor. The fall

of Philippopolis soon followed. Thus the Turks had, almost at a stroke,

separated Constantinople from nearly all contact by land with the rest of

Christendom, at the same time that they directly menaced Bulgaria and Serbia.

The Balkan states were terrified, and a league was formed between Hungary,

Serbia, Wallachia, Bulgaria, and Bosnia to oppose the Ottoman advance; but in

1371 a great Christian army was surprised at night near Chirmen on the Maritza

and dispersed by a few thousand Ottoman cavalry, and Serbia and Bulgaria were

soon reduced to the position of tributary states. Fresh hostilities led to

fresh conquests; in 1383 Sofia was taken by storm. At the same time Murad was

equally successful in his contests with the other Turkish princes of Asia

Minor. Here too he added steadily to his dominions, and finally in a decisive

battle crushed an army that had been gathered against him by his most dangerous

rival, the Emir of Karaman. Scarcely was this accomplished when he was recalled

to Europe to meet a new coalition of his Christian enemies, who had just routed

one of his generals at Toplitza in Bosnia. In 1389 the plain of Kossovo

(“blackbirds”) witnessed the first of a series of really great victories of the

Ottoman Turks over their Christian opponents, a series unbroken by a single

important defeat on land by Europeans for over two hundred years. Murad had

often prayed, before the fight, that he might die a martyr to the faith: and on

the battlefield that prayer was answered.

With Bayezid I (Yilderim,

“the Thunderbolt”) we have a new type of ruler, equal and in some respects

superior in ability to his predecessors, but in character a proud and lustful

Eastern despot, whose magnificence was only matched by his cruelty. It seems

probable that he was the first Ottoman ruler formally to assume the title of

Sultan. His first act was to put his younger brother to death in order to

render himself secure against any possible rivalry for the throne. The deed was

done on the field of Kossovo in the presence of his father's unburied corpse.

It was a precedent imitated by his successors, with but few exceptions, for

many generations to come, and the theologians justified it by the verse in the

Koran which declares that “revolution is worse than executions.”

As a soldier Bayezid was

worthy of his surname. The victory of Kossovo was actively followed up.

Bulgaria was incorporated in the Sultan's dominions; Serbia was reduced to vassalage

and Hungary threatened, while in Asia Minor the remaining Turkish princes were

driven out of their possessions, which were annexed by the conqueror. Sigismund

of Hungary, too weak to maintain the struggle alone, had turned to Western

Europe for assistance. Aided by the Pope, he succeeded in organizing a belated

crusade, led by a body of French nobles left unoccupied by a lull in the

Hundred Years' War. The expedition, however, ended in 1396 with the fatal

battle of Nicopolis, where the army of the crusaders and Hungarians was

overwhelmingly defeated by Bayezid, owing largely to its incredible lack of

discipline. Constantinople seemed inevitably doomed by this disaster. Already

it had been threatened and it was now rigorously blockaded; but, though deserted

by the West, it was to be saved for another half-century by an unexpected

diversion. Bayezid had come into conflict with another and even greater Asiatic

conqueror than himself, the terrible Tatar prince Tamerlane, who had built up a

mighty empire in Turkestan, overrun Persia, and invaded Russia and India;

shortly afterwards he was even to establish relations with, the distant king of

Castile. At first his dealings with Bayezid were friendly, since both were

warriors of the Faith; but as their boundaries approached and the victims of

each fled to the court of the other, inevitable disputes soon turned into open

hostility. To avenge a first attack Bayezid collected his forces and hastened

to meet his adversary, who had disdainfully turned aside to wage war on the

Mamelukes and devastate Syria. It was at Ankara, the scene of Ertoghrul's

exploit, that the Turks of the East and the West finally faced each other, on

the twentieth of July, 1402. Bayezid fought with all his old fury. But,

despising his enemy, he allowed himself to be outgeneraled; his army was

outnumbered, and there was treachery among his troops, some of whom saw their

former princes serving in the ranks of the enemy. By the end of the day the

Ottoman army was annihilated, and the Sultan, who had fallen from his horse in

an attempt to escape, was left an honorable prisoner in the hands of his rival.

If the defeated state had

crumbled to pieces after this fearful disaster, it would have gone down in

history merely as one of the many Eastern empires whose rapid rise had been

followed by an equally sudden fall. It had suffered indeed a stunning blow. Its

military prestige was temporarily shattered. Asia Minor had become the prey of

plundering hordes of victorious Tatars. Bayezid died in captivity in 1403, and

his sons, barely escaped from the field of battle, plunged at once into furious

civil war. No better proof can be given of the permanence of the work of their

earlier rulers than the fact that, instead of yielding to the many difficulties

by which they were beset, the Turks emerged at the end of ten years, weakened

indeed and exhausted, but with their fundamental vitality still unimpaired.

When Mohammed I, “the Restorer,” the ablest of the sons of Bayezid, had finally

triumphed over his brothers, all that was needed was a few years of rest to

enable the Turks to set forth again on the career of conquest and greatness

which the Christian world had fondly imagined to be a thing of the past.

Mohammed was exactly the sovereign demanded by the situation. In his earlier

years he had shown himself a fearless warrior; now that at last he was firmly

seated on the throne, he did his utmost to give his subjects peace, and his

honorable character commanded the respect of all men. Even his reign, however, was

not entirely free from war. His attempts to build a navy brought him into

conflict with Venice, but the Turks were as yet not quite prepared to meet the

first maritime power of the day. In 1416, outside the port of Gallipoli, the

Venetian commander Loredano destroyed the Ottoman fleet, and the Sultan, unable

to avenge himself, wisely made peace. It was reserved to his successors to

demonstrate how completely the Turks had recuperated under his rule.

Murad II (1421-51), a stern

soldier, was also a patron of art and a builder, pious, just, and honorable,

but he was destined to spend the thirty years of his reign in almost unbroken

warfare. Angered by various provocations on the part of the Greeks, he made a

determined attempt to capture Constantinople, but, for the last of many times,

the “New Rome,” thought but a shadow of her former self, beat back all the

efforts of her assailants. Foiled in this direction, Murad made a lasting

peace with the Byzantine Emperor, and turned his attention to other regions,

where he met with more success. In Asia he easily drove from their thrones most

of the Seljuk princes who had been restored by the grace of Tamerlane, and

reduced the strongest of them, the ruler of Karaman, to a position of vassalage.

In Europe he began by checking the growth of Venice, which had just bought from

the Greeks the city of Saloniki. The Sultan could not possibly permit the

ambitious republic, already too powerful in Eastern waters, to retain the most

valuable port on the Aegean Sea. In 1430 a short siege delivered it into

Murad's hands, from which there was no taking it away. In the next few years he

was mainly engaged in a series of vigorous and generally profitable campaigns

against Albania, Serbia, Wallachia, and Hungary, during which he gradually

extended his dominions at their expense. But the Turkish advance into the

Balkans was destined to be strongly opposed by two worthy champions of

Christendom: the Albanian chief, George Castriota or Skanderbeg, who kept the

Ottomans out of his native land until his death in 1467; and the Hungarian

national hero John Hunyadi, who fought the Moslems on a far larger scale though

for a shorter time. Under his leadership the Hungarians, supported by the

Poles, took the offensive against the invaders and drove them out of Serbia. So

completely, in fact, did the tables seem to be turned, that Murad, who appears

to have had a vein of mysticism in his nature, consented to a humiliating

peace, and shortly after abdicated in favor of his son Mohammed, with the idea

of spending the rest of his days in seclusion at the peaceful Anatolian town of

Manissa (Magnesia). But he did not remain long in retirement. The shameful

violation by his Christian foes of the peace to which they had pledged their

word was enough to cause him to reassume his authority, march against them, and

overwhelm them at Varna on the Black Sea in 1444. The king of Hungary was slain

on the battlefield; the sight of his head on a pike struck terror among his

troops. The papal legate Cesarini, who had urged on his Crusaders by assuring

them that no promises made to the Moslems were binding, was also killed in the

ensuing flight. Hunyadi with great difficulty made his escape to his native

land. Once more the Sultan insisted on going into retirement, this time because

he felt that he had accomplished the work that God had given him to perform;

but a revolt of the Janissaries, which gave Hunyadi the opportunity to launch a

fresh offensive, convinced him that it was his duty again to resume office. The

Janissaries were brought to order. Hunyadi was once more utterly defeated in a

second battle of Kossovo in 1448. Three years later (February 5, 1451), the

Sultan Murad died.

Christian Europe, by a

strange delusion which we shall see repeated later, imagined Murad's successor,

Mohammed II, to be a weakling, because he had twice permitted his father to

depose him. In reality, now that at the age of twenty-one he at last had the

power firmly in his grasp, he was to show the world that he was greater than

any of his predecessors, and far more dangerous. According to descriptions by

defeated Greeks and Westerners, he was fierce, unscrupulous, and determined,

passionate and debauched, faithless and cruel after a fashion unequalled even

in Ottoman annals; he was also as ominously reticent in regard to his own plans

as he was absolutely tireless in their execution. “If a hair of my beard knew

my schemes, I should pluck it out”, he once told an indiscrete official who had

ventured to question him. In war he was an indefatigable and skillful leader;

as a statesman he showed himself sagacious and far-seeing; as a lawgiver and

organizer of his empire he displayed real genius. He quoted Persian poetry as

he rode into the deserted palace of the Caesars after the storming of

Constantinople, and he gazed with deep appreciation on the glorious ruins of

Athens. He sent to the Signory at Venice to ask for a good artist to paint his

picture, and the Signory replied by dispatching Gentile Bellini to the Porte,

where he arrived in September 1479, and remained till the end of 1480. It seems

probable that he did several portraits of the Sultan, and although the

authenticity of the best known of them, which is now in the National Gallery in

London, has been contested, it gives, despite its lamentable condition, an

excellent idea of Mohammed's character and personality. Such was the man who,

like his father, was to rule for thirty years of ceaseless effort to extend his

empire, and who, though he also was to suffer two significant defeats, was

destined to accomplish more than any of his predecessors. Like his father,

also, he directed his first enterprise against the imperial city which had

defied so many attacks, and which the Ottomans ardently desired to make their

capital; and Mohammed was to succeed where Murad had failed.

The siege of Constantinople,

which began on April 6, 1453, and lasted fifty-three days, is perhaps the most

famous and dramatic in all history. It is brilliantly described by Edward

Gibbon. The Sultan had concealed his preparations with masterly cunning. He

had gathered overwhelming forces and he urged them on with passionate energy.

Huge mortars hurled great balls of stone against the city's ramparts; mines

were exploded; desperate attacks were launched at the gate of St. Romanus and

repulsed by “Greek fire”. But Mohammed soon saw that all his efforts would be

unavailing without command of the inner harbor of the Golden Horn to the

northeast of the city; and the mouth of the Golden Horn was blocked by a boom of

iron chains which all the power of the Turkish navy had been unable to break.

What could not be achieved by sea must of necessity be accomplished by land. On

the night of May 19, some seventy Turkish ships were hauled, with sails

unfurled, on greased ways which had been prepared during the preceding four

weeks, across the tip of the promontory of Pera and launched where the

Christians were unable to oppose them. From that moment onward, the result was

a foregone conclusion. On May 29, five Turkish columns simultaneously launched

furious attacks; the Genoese John Giustiniani, “whose arms and counsel were the

firmest ramparts of the city,” was wounded and fled; Constantine Palaeologus,

the last of the Greek Emperors, was slain in the ensuing confusion by an

unknown hand, and after his death the defence collapsed. Shortly after midday

the Sultan made his formal entry into St. Sophia, and gazed with wonder and

delight at what he saw. We are told that as he walked up the central aisle, he

found one of his soldiers digging out the polished stones from the flooring;

but Mohammed promptly cut him down with his scimitar. “I have given the

captives and the movables to my followers,” he declared, “but the buildings are

mine.” A moment later an imam ascended the pulpit and made the declaration of

Islam. Justinian's Holy Temple of the Incarnate Word had become a mosque. The

Eastern Empire had come to an unhonored end.

The real greatness of the new

“Kaisar-i-Rum” (Emperor of Rome) was proved quite as much by the use which he

made of his victory as by the ways in which he won it. A few days of merciless

pillaging followed the surrender. Such was the custom of the time, and it was

inevitable that it should be officially sanctioned. There were sacrilege,

murder, and rape. All sorts of precious relics of classical and Byzantine art

were destroyed. Bronze columns and imperial tombs were smashed and made over

into cannon, cannon balls, bullets, and coins. “One hundred and twenty thousand

manuscripts are said to have disappeared; ten volumes might be purchased for a

single ducat.” But Mohammed seized the earliest possible opportunity to put an

end to these desecrations. He was determined to convert his prize, the historic

metropolis of Christian Orthodoxy, into the capital of Islam (Istambul) and of

the Ottoman Empire. Most of the basilicas and monasteries were made over into

mosques, like St. Sophia; and the Sultan set a seal on what he had already done

there by the erection of the first of the four minarets by which it is flanked today.

As the buildings thus made available proved inadequate for the accommodation of

the Faithful, the succeeding age witnessed the construction of an enormous

number of Moslem almshouses, schools, and places of worship. Constantinople

began to renew its architectural youth under the inspiration of its first

Turkish master. But though Mohammed was determined to leave no doubt that he

regarded himself as the champion of Islam, his attitude towards his Christian

subjects was almost unbelievably tolerant, if measured by the standards of

contemporaneous Europe. The Patriarchate was vacant at the time the city was

taken, but three days later Mohammed ordered that a new incumbent be elected

and consecrated according to the ancient rites. A few days afterwards he

received him in solemn audience, and formally presented him with the jewelled

cross, the emblem of his dignity, after the manner of his Byzantine

predecessors. “Be Patriarch,” he declared, “and may Heaven protect thee: count

on the continuance of my good will, and enjoy all the rights and privileges of

thine office.” As long as good order was maintained, the Christian worship was

freely permitted in those churches which had not been converted into mosques;

and Easter continued to be celebrated, with traditional magnificence, in the

Christian quarter of the city. And there are plenty of other evidences that

Mohammed had no fears of the presence of a large element of Christian Europeans

in his new capital. Many of the inhabitants of- the Balkan states which he

subsequently conquered were deliberately transported to Constantinople and

established there, and the city's population soon exceeded the figure of its

late Byzantine days. Particularly characteristic was his policy towards the

Genoese, who had maintained themselves for centuries in the suburb of Galata as

a semi-independent colony, with laws and franchises of their own, and had not

seldom made serious difficulties for the Palaeologi. When he learned of the

troubles they had caused, the Sultan threatened them with wholesale slaughter.

However, on their payment of an enormous bribe he relented, and solemnly swore

that all their ancient privileges should be maintained, provided they continued

to behave themselves. To make assurance doubly sure, he gave orders that all

their fortifications be demolished.

Europe fondly hoped that

Mohammed would rest content with the organization of his first conquest, but

was doomed to disappointment. Constantinople, in the new Sultan's eyes, was not

an end but a beginning. It has been well said that for many a minor dynasty in

Southeastern Europe and Asia Minor his reign was like the Day of the Last

Judgment. In one place only did he meet serious defeat on land, when the heroic

Hunyadi, in the last weeks of his life, rolled the Ottoman armies back before

Belgrade in the summer of 1456; and the memory of that disaster continued to

rankle till it was terribly avenged, just sixty-five years later, by Mohammed's

great-grandson. Everywhere else on land the Turkish forces proved irresistible.

Between 1462 and 1464 Bosnia was subdued and its last sovereign executed; in

1467 Herzegovina was annexed. During these same years Wallachia had been made a

tributary state; Moldavia had been attacked, and the last vestiges of

independent Christian rule had been effaced from the mainland of Greece.

Albania remained unconquered until Skanderbeg's death in 1467. In the

succeeding years it became the battleground of local chieftains, Venetian

captains, and the Turks; but after Ottoman cavalry had gone around the head of

the Adriatic and attacked the Venetian mainland, it was evident that the

Moslems were destined to dominate it. In the meantime Mohammed exterminated the

Greek Empire of Trebizond; he conquered the Genoese settlements in the Crimea,

and finally reduced to vassalage the powerful Khan of the Crimean Tatars. On

the Asiatic mainland he extended his boundaries by extinguishing the last

embers of the rival Seljuk state of Karaman; and he blasted the hopes of his

enemies that a new Tamerlane would arise to defeat him by shattering the hosts

of the Turcoman sovereign of the dynasty of the White Sheep, near Terjan, in

1473. He was now the undisputed master of the whole of Anatolia.

But Mohammed was not

satisfied with land conquests alone. The Turks hitherto had been pitiably weak

on the sea. Now, with an Empire situated on two continents and one of the most

splendid ports in the world, the Sultan set himself to the task of creating a

navy. He began by closing and fortifying the Dardanelles, thereby excluding all

strangers from the Black Sea. In 1455 a Turkish fleet entered the Aegean and

conquered several of the smaller Greek islands. Venice alone made feeble

efforts to resist him; in 1463, war was declared between the republic and the

Porte, and dragged out its course for sixteen weary years. There were no great

naval battles, because Venice was careful to avoid them; but in 1470 she was

ousted from the island of Euboea, and thereafter lost all claim to the mastery

of the Eastern Mediterranean. So greatly was she impressed by the power of the

new foe, so deeply discouraged by the failure of Western Europe to support her,

that in 1479 she decided to make her peace with the Sultan, and pocket her

territorial losses in return for the maintenance of her commercial privileges.

Relieved of all anxiety of attack from the republic, Mohammed launched two new

naval expeditions in 1480. The first landed an army at Otranto in the kingdom

of Naples. The town was stormed, and the surrounding country laid waste. The whole

of Southern Italy was in abject terror. There was no prospect whatsoever of aid

from the North. But the second and greater of Mohammed's maritime ventures

proved unfortunate. It was composed of a fleet of 160 ships, carrying a

powerful army, and it was commanded to capture Rhodes, the island fortress of

the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. But it was met by an unexpectedly heroic

defence; almost it accomplished its purpose, but not quite, and the

unsuccessful commander of the Turks was relieved and disgraced. Mohammed was

planning personally to take command of a fresh expedition in the ensuing year,

when death suddenly overtook him, on May 3, 1481. Rhodes on the sea, with

Belgrade on land, remained bitter remembrances, which the Turks felt in honor bound

to wipe out; and it was to be the happy fortune of Suleiman the Magnificent, in

the years 1521 and 1522, to succeed in obliterating them both.

After such a brilliant reign,

it was almost inevitable that there should be a reaction. The Turkish troops in

Italy, left unsupported, were obliged to withdraw; while at home a war for the

throne broke out between the two sons of the late Sultan. But when the elder of

them, Bayezid II, had triumphed over his brother Jem, he showed little

inclination to continue his father's conquests. Indeed he spent most of the

first fourteen years of his reign in planning and plotting to prevent his

Christian enemies from utilizing Jem against him. The tale of the latter's

adventures at the courts of Innocent VIII and Alexander VI, of his transference

to the guardianship of Charles VIII of France, and death at Naples in the

spring of 1495, is full of dramatic incidents wholly typical of the Italian

Renaissance. Throughout his reign Bayezid waged desultory war on sea and on land,

in Europe, Asia, and Africa, but never with decisive results. The Turks, who

had become accustomed to the dramatic victories of Mohammed, grew increasingly

restless and discontented. Less and less was the Sultan able to control his

subjects, his soldiery, and his turbulent children, and in 1512 a series of

revolts ended in his abdication in favor of his youngest son Selim, who had won

the support of the Janissaries. Bayezid was permitted to retire from

Constantinople to his birthplace; but on the way thither he died, poisoned—so

it was popularly believed —by his Jewish doctor at the behest of his successor.

The brief reign of Selim “the

Terrible” (1512-20) witnessed a speedy and ominous resumption of his grandfather's

conquests. Indeed the new Sultan, in the first five years of his rule, added

more territory to his dominions than had any of his predecessors; all of it, be

it noted, was won from his own coreligionists. His Christian neighbors to the

westward thanked God that he elected to leave them alone, and sent embassy

after embassy to his court to beg on bended knees for the renewal of truces and

capitulations. They had good reason to fear, for though the new Sultan took

delight in the society of scholars and theologians, wrote poetry himself in

three languages, and even sought refuge from the cares of state by occasional

indulgence in opium, he was first and foremost a savage warrior and a

bloodthirsty despot. He began, in orthodox fashion, by ridding himself of all

possible rivals for the throne. His two elder brothers and eight nephews were

disposed of in rapid succession. He also made it clear from the outset that he

proposed to tolerate no independence on the part of any of his subordinates,

many of whom throughout his reign were handed over without warning to the

executioner; hence the curse which became proverbial among the Turks, “May you

be the vizir of the Sultan Selim!” Having regulated matters to his satisfaction

at Constantinople and gathered all the reins of power into his own hands, he

surveyed the state of his neighbors to the East and the South.

At Selim's accession the

Ottoman dominions included practically all of Asia Minor, but Persia, which for

the preceding century and a half had been split up into a number of minor

principalities, had now at last begun to gather itself together under a new

dynasty, ably represented by Ismai‘1 I, who in 1499 had been proclaimed Shah.

The presence on his flank of what now threatened to become a powerful state was

enough to rouse all the fighting spirit of Selim. The fact that Ismail belonged

to the Sufi sect of the Shiite form of Islam was sufficient to fire his burning

zeal for the maintenance of Sunnite orthodoxy. Sufi doctrines had of late begun

to spread among the Sultan's own subjects, and Selim gave orders that all who

were tainted with this heresy should be exterminated on a given day. It is said

that 40,000 persons were massacred in the ensuing purge. Having thus shown the

strength of his own sentiments, and obtained from the head of his clergy a declaration

that there was more merit in killing one heretic Persian than seventy

Christians, Selim led a great force across Asia Minor to the eastward. Shah

Ismail, who had no infantry and not a single cannon, retreated, laying waste

the country behind him as he went; but Selim was not the man to be deterred by

any “scorched earth” policy. The sufferings of his army were terrible; even the

Janissaries murmured, and on one occasion the Sultan's own tent was riddled

with bullets; but Selim never wavered; and his persistence was at last

rewarded, when Ismail was forced to accept battle at Chaldiran (August 24,

1514), in order to save his capital, Tabriz. The Turkish troops were exhausted,

and most of their horses were gone; but their infantry and artillery sufficed

to win the day. Shah Ismail was wounded; his baggage and harem fell into the

hands of the enemy. Fresh outbreaks of the Janissaries prevented the Sultan

from following up his victory to the extent that he wished; nevertheless in the

course of the next two years he incorporated into his possessions the Jezirat

or northern part of Mesopotamia and the mountainous region of Kurdistan, where,

however, he left the tribal government of the turbulent inhabitants practically

undisturbed. He returned to Constantinople in triumph; and after punishing the

instigators of the recent mutinies, he reorganized his Janissaries in such

fashion as to relieve him of all fear of disobedience in the future.

Even before the end of his

Persian campaigns, Selim had turned his attention to another rival. Ever since

the middle of the thirteenth century, Egypt, with its dependencies in Syria and

on the Red Sea, including the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, had been ruled

by the famous Mamelukes. Originally a body of slaves, they had finally become

masters of the land; and they had kept up their numbers by the old method of

purchase, first of Turkish, later of Circassian, children. This military

aristocracy of a few thousand cavalrymen, whose Soldan was merely their chief,

were intensely proud of their past, and promised to be a formidable foe. But,

aided by treachery, Selim defeated them near Aleppo on August 24,1516, their

leader perishing in the ensuing flight. As Damascus surrendered without

resistance and the inhabitants of Lebanon also submitted, this victory made

Selim master of Syria and Palestine, whose administration he proceeded to

reorganize before pushing on into Egypt itself. On January 23, 1517, at

Ridania, the Mameluke cavalry, fighting with desperate bravery, were mowed down

by his cannon. Twenty thousand men are said to have been left dead on the

field. Cairo was now taken, and Tuman Beg, the last Mameluke Soldan, was

pursued until he was betrayed by an Arab chief and hanged at the gates of the

town. The Mamelukes as a body, however, were not exterminated or even deprived

of all power. Selim left the administration of Egypt as it was, with a Mameluke

bey at the head of each of its twenty-four provinces; but over them all, in

place of a Soldan of their own, he placed a Turkish governor.

Selim reaped other rewards

from the conquest of Egypt besides increase of territory and military fame. He

also won the proud title of “Protector of the Holy Cities,” with the

overlordship of Mecca and Medina, a dignity to which both he and his successors

attributed great importance. The story—generally accepted until very recently—

that he took the title of Caliph from the last Abbasside, whom he found in

Cairo, is of more doubtful authenticity. It now seems clear that some of his

predecessors had occasionally been addressed as Caliph (though in a somewhat

limited sense) by other Moslems, but that Selim and Suleiman took pains to

avoid the use of the title. The “Ottoman legists of their time inclined to the

view that the Caliphate had [really] lasted only thirty years—until the death

of Ali,” the last of the four successors of the Prophet; and the first

diplomatic document known to have called the Turkish Sultan Caliph Is the

treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji with Russia in 1774. Of course the title died with

the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1922—24. But even if we eliminate

his claims to the Caliphate, we must admit that Selim had rendered notable

service to the Turks and to Islam. The last three years of his life were spent

in peace; but while officially absorbed in problems of internal government, he

was also getting ready, with characteristic secrecy and thoroughness, another

great expedition, presumably intended to wipe out the disgrace of Rhodes. The

Christian West, which he had hitherto spared, was in an agony of suspense. But

death interrupted him in the midst of his preparations, on September 22, 1520,

in his fifty-fourth year.

Youth and Accession of Suleiman.

Contemporaneous Europe

Selim the Terrible left

behind him only one son, the Sultan Suleiman, surnamed by Christian writers

“the Great” or “the Magnificent”, and by his own people “El Kanuni” or “the

Legislator”. We know almost nothing of his early years; but it seems clear that

he was born in the latter part of the year 1494 or possibly in the early months

of 1495, and that his mother, whose name was Hafssa Khatoun, was a woman of

rare charm and intelligence. Some writers have maintained that she was a

Circassian or a Georgian; but there is much to support the statement of Jovius

that she was the daughter of the Khan of the Crimean Tatars. The power and

popularity which both her husband and her offspring subsequently enjoyed at

Kaffa (Feodosia) lend added weight to this conclusion. Indeed, there is good

reason to believe that Suleiman spent at least a portion of his boyhood there

among his mother's kinsmen. But as his father was only the youngest of the

eight sons of Bayezid II, the infant's chances of ever coming to the throne can

hardly, at the outset, have appeared promising.

Sixteen years later, however,

the situation had entirely changed. Suleiman was thrust prominently into the

foreground, and his prospects were much enhanced by the family troubles which

convulsed the last years of his grandfather's life and finally cost him his

throne. The number of Bayezid's surviving sons had by this time been reduced

to three; and one of them, Korkud, had little ambition to rule. It speedily

became evident that the only serious rivals for the succession would be

Bayezid's oldest and favorite son, Achmed, and his youngest, the “Terrible”

Selim. Both were governors of provinces; and since it would be essential to

gain control of the capital, the treasury, and the household troops as soon as

the old Sultan should die, the relative proximity of these provinces to

Constantinople was a matter of primary importance. Achmed had been given

Amasia, in North Central Asia Minor, while Selim had been stationed at

Trebizond, farther eastward; but Achmed's advantage was almost nullified by the

fact that Bayezid unexpectedly appointed Selim's sixteen-year-old son,

Suleiman, to the governorship of the district of Boli, which intervenes between

Amasia and Constantinople, and thus blocked Achmed's way in the future race for

the throne. The appointment of young princes of the blood to rule regions more

or less remote from the capital was a practice too common in Ottoman statecraft

to merit special attention, though the selection of Suleiman is, under the

circumstances, very difficult to explain. In any case we know that Achmed

complained so loudly that Bayezid transferred his grandson from Boli to Kaffa

in the Crimea. Thither he was speedily followed by his father Selim, who, being

convinced that as long as he remained at Trebizond his chances of the

succession were slight, was determined to get nearer to the main theatre of

operations. At Kaffa he appears immediately to have taken matters into his own

hands, practically superseding his son and acting like an independent ruler,

and the mass of the Crimean Tatars rallied to his standard. When Bayezid

ordered him to return to Trebizond, he replied by begging for a governorship in

the Balkans, so that he might have a chance to fight against the Christians,

and, above all, to be near enough to his imperial sire to kiss his hand. It was

the custom, so he pointed out, “for governors of provinces to do so every year”.

Thrice was the request repeated, and thrice refused. Nevertheless, the

insubordinate prince started westward at the head of some 25,000 men, and soon

was joined by reinforcements. We need not follow the details of the ensuing

confusion. At Chorlu, near Constantinople, Selim's forces were met and routed

by his father's trained Janissaries, who charged to the cry of “Death to the

bastard!”, but the victory had no lasting results. Selim made his escape to the

Crimea. His father tried in vain to pacify him by offering him the governorship

of the great province of Semendria, on the Danube; but Selim was in no mood for

compromise. His reckless bravery had won him the admiration and loyalty of the

Janissaries with whom he had just fought, and without the Janissaries the cause

of Bayezid was lost. Early in 1512 Selim reappeared at Constantinople, and

forced his father to abdicate.

During all these troubles we

hear little or nothing of Suleiman; but after his father had obtained the

throne, he was summoned to his presence at Constantinople and left in charge

there while Selim went off to end the fratricidal strife in Asia. When at

length the “Terrible” Sultan had disposed of his brothers and nephews, he

turned his attention to the conquest of Persia. Suleiman did not accompany him

on the ensuing campaigns, but remained behind, this time as governor of

Adrianople. There are occasional mentions of communication between the two; as

when, writing from Tabriz, Selim announced his great victory over the Persians

to his son as well as to the Khan of the Tatars, the Soldan of Egypt, and the

Doge of Venice. At the close of the Persian and Egyptian wars the Sultan returned

in triumph to his capital, and then proceeded to Adrianople, whence, eight days

later, Suleiman departed with much pomp for Manissa, the chief town of the

province of Sarukhan on the coast of Asia Minor, to which he was now assigned.

We have no means of knowing what the relations between father and son at this

period really were. Even if it does not seem probable that they were

affectionate, we have no sure proof of the rumors which have come down to us

that the Sultan really hated his offspring, or thought to put him to death. The

tale that he once sent the prince a poisoned garment, which was prudently tried

on a page who died from its effects, is undoubtedly an absurd fable. But it

seems not improbable that Suleiman's prompt departure from Adrianople was all

that availed to save him from hostile intent on the part of his terrible sire;

for even though the Sultan had no other heir, rebellions of princes against

their parents had been all too common in Oriental history. Selim's own conduct

toward his father had been the most recent instance of it, and his suspicious

and ruthless nature was ever on the lookout for danger. Four years earlier,

when the Janissaries had mutinied during the Persian campaign, they are said to

have threatened to replace their sovereign with his son. However all this may

be, Suleiman himself was now established in comparative safety at Manissa, and

the period during which he was doomed to remain in obscurity was destined to be

unexpectedly brief.

The death of Sultan Selim,

according to custom, was kept concealed until his successor should be notified

in time to arrive and prevent any disorder among the soldiery. In the present

case it was not found necessary to preserve the secret to the very end, for the

interval was short. On Sunday, September 30, 1520, only eight days after his

father's decease, the new Sultan reached Constantinople, where he was welcomed

by the Janissaries, who clamored for the usual gifts on the accession of a new

master. At dawn on the following day, Suleiman issued forth from the inner

rooms of the palace to receive the homage of the high officials. That afternoon

he went to the gate of the city to meet the funeral procession with his

father's corpse, which he then escorted to the mosque where the burial service

took place. His first official decree was an order for the erection of a

mortuary chapel with a mosque and a school in honor of the departed —the mighty

conqueror of Persian and Mameluke. Two days later there was distributed the bakshish or donation, not only to the

Janissaries, who had demanded and received more than had been given them at the

accession of Selim, but also to the other household troops and to various civil

officials. Then followed acts of mercy and justice. Six hundred Egyptian captives

were set free, and a number of merchants, whose goods had been confiscated for

trading with Persia, received an indemnity; on the other hand, a few salutary

executions of evil-doers showed that the new ruler intended to be respected as

well as beloved.

The reign certainly opened

under most favorable auspices. According to an Oriental superstition, there

arises at the beginning of each century a great man who is destined to dominate

it, or, in Turkish phrase, “to take it by the horns”. Suleiman also profited

from the Moslem belief that the number ten, that of the fingers and toes, of

the Commandments in the Pentateuch, of the disciples of Mohammed, of the parts

and variants of the Koran, and of the “astronomical Heavens” of Islam, is the

most perfect and fortunate of all numbers. Suleiman was born in the year 900 of

the Hegira, that is to say, by Oriental reckoning, in the first year of the

tenth century; he was also the tenth Sultan of the Ottoman line, and had been

given the imposing name of Suleiman or Solomon, which is especially venerated

in the East. He was, in fact, the first acknowledged Ottoman sovereign to bear

that name; for the Suleiman who conquered Gallipoli in 1356 had died before his

father Orkhan and was therefore never a real Sultan, while the Suleiman who

disputed the throne with Mohammed I has always been regarded as a pretender by

Turkish historians. When the latter speak of “El Kanuni” as “Suleiman II”, it

is in the sense of the second Solomon of the world. It is noteworthy to what

extent the destinies of the Europe of that time had been delivered into the

hands of young men. Suleiman at his accession was twenty-six, the same age as

Francis I; Henry VIII of England was three years older; Charles V, Emperor and

king of Spain, was but twenty, and Louis, king of Hungary and Bohemia, only

fourteen. Even the Pope, Leo X, was not quite forty- five. The new Sultan had

already had some ten years of experience in the art of government; and the

terrible severity of his father's reign, while it had maintained the bonds or

despotic discipline, offered an easy popularity to a more gracious successor.

Never had the empire been more tranquil at home or more respected abroad.

The reports of the Venetian

ambassadors shed precious light on the character and appearance of the new

Sultan throughout his reign, and it is significant that Titian should have

painted him in his “Ecce Homo” in 1543 and Veronese in his “Marriage at Cana”

some fifteen years later. Our earliest description of him is from the pen of

Bartolomeo Contarini, and is dated October 15, 1520, less than a month after

his accession. It tells us that “he is twenty-five years of age, tall, but

wiry, and of a delicate complexion. His neck is a little too long, his face

thin, and his nose aquiline. He has a shadow of a mustache and a small beard;

nevertheless he has a pleasant mien, though his skin tends to pallor. He is

said to be a wise Lord, fond of study, and all men hope for good from his

rule”. Yet despite the apparent slightness of his frame, his early training and

experiences at Boli and Kaffa had sufficed to furnish him with a body able to

endure the strain of thirteen hard campaigns, and one authority tells us that,

like other Turkish children of noble birth, he was taught to labor at a trade, so

that, if necessary, he should be able to earn his bread by the sweat of his

brow. On the other hand, he had spent at least one-third of his life previous

to his accession at Constantinople, where he had acquired the ways and manners

of the Turkish gentilhomme par excellence. Indeed, his popularity in the

capital was an asset of enormous importance to him till the end of his days.

Unlike his father, his interests and attention were directed rather to the West

than to the East, to Europe rather than to Asia. He took no pleasure in Persian

philosophy or poetry, though he delighted in stories of conquerors like

Alexander the Great. Especially did he pride himself on his ability to converse

with his officers —the great majority of whom had been born in the Balkans— in

their native dialects. He had no enthusiasm for the persecution of Moslem

heretics, nor did he believe that it was his sacred duty to extirpate

Christians. Certainly he was no religious fanatic. On the other hand, no one of

his predecessors had ever had anything like such a lofty conception of the

dignities and responsibilities of his office as “Commander of the Faithful”.

Every important event of his long reign furnishes fresh evidence of this

fundamental fact, and many who had not fully grasped it were destined to suffer

cruelly for their mistake. The new Sultan looked out on the world around him

with a calm, cold, perhaps slightly whimsical gaze, as if wondering where the

demands of his own position, and the insolence of its prospective challengers,

would first compel him to strike.

As Suleiman was Selim’s only

son, and as Selim had made such a clean sweep of all his relatives at the time

of his own accession, there was no danger that the new Sultan’s right to the

throne would be disputed by any scion of the house of Osman. In only one corner

of the broad extent of his dominions did the change of sovereigns produce a

serious revolt. A certain Ghazali, a bey, apparently of Slavonic birth, had

deserted his Mameluke master at the time of the conquest of Egypt, and had been

rewarded for his treachery by Selim with the governorship of Syria. He now

deluded himself into thinking that the time had come for him to win complete

independence. He easily made himself master of Damascus, Beirut, and Tripoli, with

most of the adjacent seacoast; but Aleppo defended itself stoutly till Ferhad

Pasha, the merciless third vizir, arrived with an army to relieve it. Ghazali

retreated on Damascus, where he was speedily and completely defeated; he was

caught, moreover, while attempting to escape, and was killed by one of his own

adherents. The affair had certain ominously significant aftermaths. When the

head of the defeated rebel was brought back to Constantinople, the Sultan

proposed to send it, as a token of friendly sentiment, to the republic of

Venice; and the Venetian resident at the capital had no little difficulty in

dissuading him from so doing. Even the victorious Ferhad Pasha was ultimately

rewarded with death. On his way back from Damascus, he had invited the Turkish

ruler or an adjacent sanjak to his camp. When the latter appeared with his four

sons, Ferhad Pasha reproached them for their failure adequately to support him,

and finally handed all of them over to the executioner. Suleiman was not the

man to tolerate such high-handed conduct. On the other hand, Ferhad Pasha had

married the Sultan's sister, and the latter pleaded her husband's cause so

eloquently that Ferhad Pasha was finally transferred to the governorship of the

Balkan province of Semendria, with a large salary, in the hope that this mark

of imperial favor and proximity to Constantinople would make him see reason.

But it was all in vain. Ferhad Pasha was as ruthless and insubordinate as ever

in his new domain. When summoned by Suleiman to explain his conduct, he was so

insolent in his replies that the executioners were sent for at once. It would

appear that he gave them a fight for their lives before he was finally

overpowered and killed (November 1, 1524). We are also told that his widow made

haste to present herself, clad in deep mourning, before the Sultan, and dared

to express the wish that she would soon have the privilege of wearing mourning

for her brother as well. But the real significance of Ferhad Pasha's end, as

well as of many other contemporaneous episodes, was that it proved that the new

Sultan proposed to be master in his own house, and Suleiman's Eastern neighbors

were prompt to read the signs of the times. Long before Ferhad Pasha had been

finally disposed of, the Persian Shah Ismail, who had been watching and waiting

on the course of events, took pains to send the friendliest messages of

congratulation to Suleiman.

The powers of Christian

Europe were less wise. It will be worthwhile to devote a couple of paragraphs

at this point to their attitude towards the recent progress of the Turks.

During the weak reign of

Bayezid II, King Louis XII of France, “the eldest son of the Church”, and heir

to inspiring memories of the mediaeval struggles of the Cross against the

Crescent, had dispatched two expeditions, in 1499 and 1501, to dislodge the

Moslems from their island strongholds in the Levant. Both, however, had

disastrously failed, owing chiefly to the refusal of the Venetians to fulfill

their promises of cooperation; and now the memory of them was revived, with

acid clarity, after the accession of the “Terrible” Selim in 1512. If the

Christians had been defeated when the Turkish Sultan was so notoriously inefficient,

what could they possibly hope to accomplish against an enemy now led by an able

ruler who literally thirsted for war? No wonder that Western Europe trembled.

There was, of course, much talk of new crusading. Pope Leo X kept constantly

harping on the necessity for it. During Selim's Persian and Egyptian campaigns,

he had repeatedly pointed out the opportunity thereby offered. If the Sultan

should be victorious, he declared, he would be much more dangerous and

therefore should be attacked at once; if, on the other hand, he should be

defeated, there would be the best of all chances to render him harmless

forever. In principle no one seemed to disagree with the Pope. King Francis I

of France was especially zealous for a crusade. When he was striving to win the

imperial crown, in 1519, his agents were instructed to emphasize his fitness to

lead an army against the Moslems. He himself declared, in typically

grandiloquent fashion, that if elected he would engage within three years

either to reach Constantinople, or else to perish on the way. The Emperor

Maximilian and the other sovereigns of Western Europe all promised their loyal

support for the great cause; but when it came to translating their words into

deeds every one of them drew back. They were far too anxious to get the better

of one another to unite for a common cause. The smaller states to the east of

them were in terror of their lives.

Under all the circumstances

it is no wonder that the powers of Western Europe hailed the news of the death

of Selim with feelings of profound relief. Most of them had been convinced that

the “Terrible” Sultan, after finishing off his own coreligionists, intended to

launch devastating attacks against the Christians. Rumors that he was preparing

to assault Rhodes had already reached them. Moreover, it was well known that

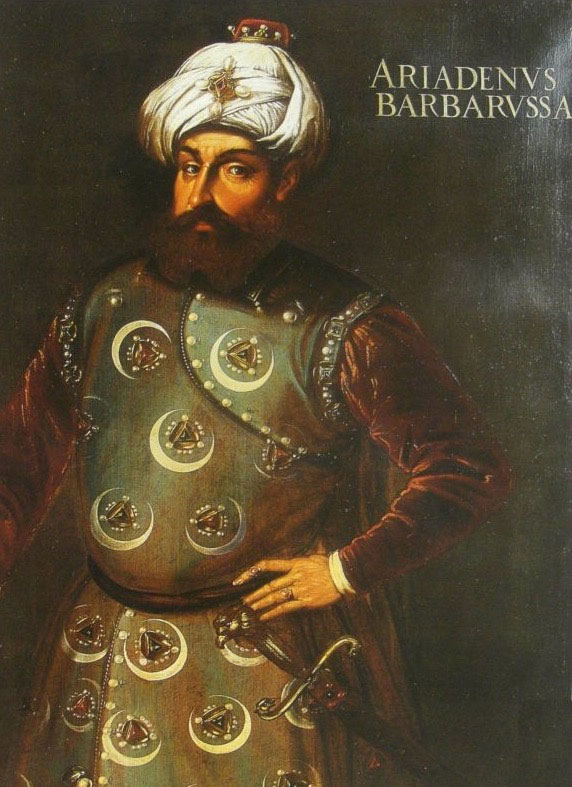

the savage corsair Khaireddin Barbarossa, whose elder brother Aruj had made

life miserable for the Spaniards in the western basin of the Mediterranean for

many years before his death in 1518, had sent an envoy to Constantinople to

declare himself the vassal of the Sultan. It looked as if Selim was planning to

add North Africa to his empire, and possibly even to attempt the reconquest of

Spain. And then came the happy and unexpected news of Selim's early death. The

West knew nothing of Suleiman. “It seemed to all men”, as Jovius puts it, “that

a gentle lamb had succeeded a fierce lion, ... since Suleiman himself was but

young and of no experience ... and altogether given to rest and quietness”.

When Pope Leo had “heard for a surety that Selim was dead, he commanded that

the Litany and common prayers be sung throughout all Rome, in which men should

go barefoot”.

Christian Europe was soon to

discover that it was sadly mistaken in the estimate thus hastily made. On the

strength of it men ceased, for five most crucial months, to trouble themselves

about the affairs of the Levant. The Pope, indeed, continued to dwell upon the

opportunities for a great crusade, but the sovereigns of Western Europe still

hung back. All of them knew that for many years past contributions which had

been made for the fight against the Moslems had been diverted to other uses

less holy and far nearer home; moreover, whereas in Selim's day they had felt

that the sacred cause was well-nigh hopeless anyway, they now were convinced

that everything was so serene that there was no reason that they should bestir

themselves. It is really extraordinary how completely they failed to comprehend

the character and abilities of the new Sultan. They thought that he had no

knowledge of the duties of his office; whereas, as a matter of fact, he had had

more experience of the art of government previous to his accession than had any

one of his predecessors. It is true that Suleiman was not of a bloodthirsty

disposition, nor did he delight in war as a mere pleasure. On the other hand,

as we have already pointed out, he was thoroughly imbued with a sense of his

own position and of the duties as well as the dignities that it implied. We

must not forget that the Ottoman state regarded all its members, from the