DIVINE HISTORY |

|

|

|

|

THE SELEUCID EMPIRE. 358-251 BC. HOUSE OF SELEUCUS

CHAPTER 1

HELLENISM IN THE

EAST

It is a common phrase we hear—“the unchangeable

East”. And yet nothing strikes the thoughtful traveller in the East more than

the contrast between the present and a much greater past whose traces meet him

at every turn. He seems to walk through an enormous cemetery. Everywhere there

are graves—graves in the lonely hills, where there are no more living, graves

not of persons only, but of cities; or again, there are cities not buried,

whose relics protrude forlornly above ground like deserted bones. Beside the

squalid towns, the nomads’ huts, the neglected fields of today are the vestiges

of imperial splendour, of palaces and temples, theatres and colonnades, the

feet of innumerable people. So utterly gone and extinct is that old world, so

alien is the sordid present, that the traveller might almost ask himself

whether that is not a world out of all connection with this, whether that other

race is not severed from the men he sees by some effacing deluge. And yet there

is this very peculiarity in the sensations that a European traveller must

experience at the sight of these things, that he becomes aware of a closer

kinship between himself and some of these fragments of antiquity than exists

between himself and the living people of the land. The ruins in question do not

show him the character of some strange and enigmatic mind, like those of Egypt

or Mexico, but the familiar classical forms, to which his eye has grown used in

his own country, associated in his thought with the civilization from which his

own is sprung. What do these things here, among people to whom the spirit that

reared and shaped them is utterly unknown? The European traveller might divine

in the history which lies behind them something of peculiar interest to

himself. It is a part of that history which this book sets out to

illuminate—the work accomplished by the dynasty of Seleucus in its stormy

transit of the world’s stage two thousand years ago.

It is not so much the character of the kings

which gives the house of Seleucus its peculiar interest. It is the

circumstances in which it was placed. The kings were (to all intents and

purposes) Greek kings; the sphere of their empire was in Asia. They were called

to preside over the process by which Hellenism penetrated an alien world,

coming into contact with other traditions, modifying them and being modified. Upon

them that process depended. Hellenism, it is true, contained in itself an

expansive force, but the expansion could hardly have gone far unless the

political power had been in congenial hands. As a matter of fact, it languished

in countries which passed under barbarian rule. It was thus that the Seleucid

dynasty in maintaining itself was safeguarding the progress of Hellenism. The

interest with which we follow its struggles for aggrandizement and finally for

existence does not arise from any peculiar nobility in the motives which

actuate them or any exceptional features in their course, but from our knowing

what much larger issues are involved. At the break-up of the dynasty we see

peoples of non-Hellenic culture, Persians, Armenians, Arabs, Jews, pressing in

everywhere to reclaim what Alexander and Seleucus had won. They are only

checked by Hellenism finding a new defender in Rome. The house of Seleucus,

however feeble and disorganized in its latter days, stood at any rate in the

breach till Rome was ready to enter on the heritage of Alexander.

But what does one mean by Hellenism?

That characteristic which the Greeks themselves

chiefly pointed to as distinguishing them from “barbarians” was freedom.

The barbarians, they said, or at any rate the Asiatics, were by nature slaves.

It was a proud declaration. It was based upon a real fact. But it was not

absolutely true. Freedom had existed before the Greeks, just as civilization

had existed before them. But these two had existed only in separation. The

achievement of the Greeks is that they brought freedom, and civilization into

union.

ELEUTHERIA

WHAT was the special gift of Greece to the

world? The answer of the Greeks themselves is unexpected, yet it is as clear as

a trumpet: Eleutheria, Freedom. The breath of Eleutheria fills the sail of Aeschylus' great verse, it blows

through the pages of Herodotus, awakens fierce regrets in Demosthenes and

generous memories in Plutarch. "Art, philosophy, science," the Greeks

say, "yes, we have given all these; but our best gift, from which all the

others were derived, was Eleutheria."

Now what did they mean by that?

They meant the Reign of Law.

Aeschylus says of them in The Persians :

ATOSSA. Who is their shepherd over them and

lord of their host?

CHORUS. Of no man are they called the slaves or

subjects.

Now hear Herodotus amplifying and explaining

Aeschylus. "For though they are free, yet are they not free in all things.

For they have a lord over them, even Law, whom they fear far more than thy

people fear thee. At least they do what that lord biddeth them, and what he

biddeth is still the same, to wit that they flee not before the face of any

multitude in battle, but keep their order and either conquer or die". It

is Demaratos that speaks of the Spartans to King Xerxes.

Eleutheria the Reign of Law or Nomos. The word Nomos begins with the meaning “custom” or “convention”, and ends by

signifying that which embodies as far as possible the universal and eternal

principles of justice. To write the history of it is to write the history of

Greek civilization. The best we can do is to listen to the Greeks themselves

explaining what they were fighting for in fighting for Eleutheria. They will not put us off with abstractions.

No one who has read The Persians forgets

the live and leaping voice that suddenly cries out before the meeting of the

ships at Salamis: “Onward, Sons of the Hellenes! Free your country, free your

children, your wives, your fathers’ tombs and seats of your fathers’ gods! All

hangs now on your fighting!". This, then, when it came to action, is what

the Greeks meant by the Reign of Law. It will not stem so puzzling if you put

it in this way: that what they fought for was the right to govern themselves.

Here as elsewhere we may observe how the struggle of Greek and Barbarian fills

with palpitating life such words as Freedom, which to dull men have been apt to

seem abstract and to sheltered people faded. For the Barbarians had not truly

laws at all. How are laws possible where “all are slaves save one”, and he

responsible to nobody? So the fight for Freedom becomes a fight for Law, that

no man may become another's master, but all be subject equally to the Law,

“whose service is perfect freedom”.

That conception was wrought out in the stress

of conflict with the Barbarians, culminating in the Persian danger. On that

point it is well to prepare our minds by an admission. The quarrel was never a

simple one of right and wrong. Persia at least was in some respects in advance

of the Greece she fought at Salamis; and not only in material splendour. That

is now clear to every historian; it never was otherwise to the Greeks

themselves. Possessing or possessed by the kind of imagination which compels a

man to understand his enemy, they saw much to admire in the Persians their

hardihood, their chivalry, their munificence, their talent for government. The

Greeks heard with enthusiasm (which was part at least literary) the scheme of

education for young nobles “to ride a horse, to shoot with the bow, and to

speak the truth!”. In fact the two peoples, although they never realized it,

were neither in race nor in speech very remote from one another. But it was the

destiny of the Persians to succeed to an empire essentially Asiatic and so to

become the leaders and champions of a culture alien to Greece and to us. In

such a cause their very virtues made them the more dangerous. Here was no

possible compromise. Persia and Greece stood for something more than two

political systems; the European mind, the European way of thinking and feeling

about things, the soul of Europe was at stake. There is no help for it; in such

a quarrel we must take sides.

Let us look first at the Persian side. The

phrase I quoted about all men in Persia being slaves save one is not a piece of

Greek rhetoric; it was the official language of the empire. The greatest

officer of state next to the King was still his “slave” and was so addressed by

him. The King was lord and absolute. An inscription at Persepolis reads “I am

Xerxes the Great King, the King of Kings, the King of many-tongued countries,

the King of this great universe, the Son of Darius the King, the Achaemenid.

Xerxes the Great King saith: By grace of Ahuramazda I have made this portal

whereon are depicted all the countries”.

The Greek orator Aeschines says, “He writes

himself Lord of men from the rising to the setting sun”. The letter of Darius

to Gadatas it exists today is addressed by “Darius the son of Hystaspes, King

of Kings”. That, as we know, was a favourite title. The law of the land was summed

up in the sentence: “The King may do what he pleases”. Greece saved us from

that.

No man might enter the sacred presence without

leave. Whoever was admitted must prostrate himself to the ground. The emperor

sat on a sculptured throne holding in his hand a sceptre tipped with an apple

of gold. He was clad in gorgeous trousers and gorgeous Median robe. On his head

was the peaked kitaris girt with the crown, beneath which the formally curled

hair flowed down to mingle with the great beard. He had chains of gold upon him

and golden bracelets, a golden zone engirdled him, from his ears hung rings of

gold. Behind the throne stood an attendant with a fan against the flies and held

his mouth lest his breath should touch the royal person. Before the throne stood

the courtiers, their hands concealed, their eyelids stained with kohl,

their lips never smiling, their painted faces never moving. Greece saved us

from all that.

The King had many wives and a great harem of

concubines one for each day of the year. You remember the Book of Esther.

Ahasuerus is the Greek Xerxes. There is in Herodotus a story of that court

which, however unauthentic it may be in details, has a clear evidential value.

On his return from Greece Xerxes rested at Sardis, the ancient capital of

Lydia. There he fell in love with the wife of his brother Masistes. Unwilling

to take her by force, he resorted to policy. He betrothed his son Darius to

Artaynte, the daughter of Masistes, and took her with him to Susa (the Shushan

of Esther), hoping to draw her mother to his great palace there, “where were

white, green and blue hangings, fastened with cords of fine linen and purple to

silver rings and pillars of marble”. In Susa, however, the King experienced a

new sensation and fell in love with Artaynte who returned his affection. Now

Amestris the Queen had woven with her own hands a wonderful garment for her

lord, who inconsiderately put it on to pay his next visit to Artaynte. Of

course Artaynte asked for it, of course in the end she got it, and of course

she made a point of wearing it. When Amestris heard of this, she blamed, says

Herodotus, not the girl but her mother. With patient dissimulation she did

nothing until the Feast of the Birthday of the King, when he cannot refuse a

request. Then for her present she asked the wife of Masistes. The King, who

understood her purpose, tried to save the victim; but too late. Amestris had in

the meanwhile sent the King’s soldiers for the woman; and when she had her in

her power she cut away her breasts and threw them to the dogs, cut off her

nose and ears and lips and tongue, and sent her home.

It may be thought that the Persian monarchy

cannot fairly be judged by the conduct of a Xerxes. The reply to this would

seem to be that it was Xerxes the Greeks had to fight. But let us choose

another case, Artaxerxes II, whose life the gentle Plutarch selected to write

because of the mildness and democratic quality which distinguished him from

others of his line. Yet the Life of Artaxerxes would be startling in a chronicle

of the Italian Renaissance. The story which I will quote from it was probably

derived from the Persian History of Ktesias, who was a Greek physician at the

court of Artaxerxes. This Ktesias, as Plutarch himself tells us, was a highly

uncritical person, but after all, as Plutarch goes on to say, he was not likely

to be wrong about things that were happening before his eyes. Here then is the

story, a little abridged.

She, that is, Parysatis, the queen-mother,

perceived that he, Artaxerxes, the King, had a violent passion for Atossa, one

of his daughters. When Parysatis came to suspect this, she made more of the

child than ever, and to Artaxerxes she praised her beauty and her royal and

splendid ways. At last she persuaded him to marry the maid and make her his

true wife, disregarding the opinions and laws (Nomoi) of the Greeks; she said

that he himself had been appointed by the god (Ahuramazda) a law unto the

Persians and judge of honour and dishonour. Atossa her father so loved in

wedlock that, when leprosy had overspread her body, he felt no whit of loathing

thereat, but praying for her sake to Hera (Anaitis?) he did obeisance to that

goddess only, touching the ground with his hands; while his satraps and friends

sent at his command such gifts to the goddess that the whole space between the

temple and the palace, which was sixteen stades (nearly two miles) was filled

with gold and with silver and with purple and with horses.

Artaxerxes afterwards took into his harem

another of his daughters. The religion of Zarathustra sanctioned that. It also

sanctioned marriage with a mother. According to Persian notions both Xerxes and

Artaxerxes behaved with perfect correctness. The royal blood was too near the

divine to mingle with baser currents. There is no particular reason for

believing that Xerxes was an exceptionally vicious person, while Artaxerxes

seemed comparatively virtuous. It was the system that was all wrong. What are

you to expect of a prince, knowing none other law than his own will, and

surrounded from his infancy by venomous intriguing women and eunuchs? Babylon

alone used to send five hundred boys yearly to serve as eunuchs. I think we may

now leave the Persians.

Hear again Phocylides: “A little well-ordered

city on a rock is better than frenzied Nineveh”. The old poet means a city of

the Greek type, and by “well-ordered” he means governed by a law which

guarantees the liberties of all in restricting the privileges of each. This,

the secret of true freedom, was what the Barbarian never understood. Sperthias

and Boulis, two rich and noble Spartans, offered to yield themselves up to the

just anger of Xerxes, whose envoys had been flung to their death in a deep

water-tank. On the road to Susa they were entertained by the Persian grandee

Hydarnes, who said to them: “Men of Sparta, wherefore will ye not be friendly

towards the King? Beholding me and my condition, ye see that the King knoweth

how to honour good men. In like manner ye also, if ye should give yourselves to

the King (for he deemeth that ye are good men), each of you twain would be

ruler of Greek lands given you by the King”. They answered: “Hydarnes, thine

advice as touching us is of one side only, whereof thou hast experience, while

the other thou hast not tried. Thou understandest what it is to be a slave, but

freedom thou hast not tasted, whether it be sweet or no. For if thou shouldst

make trial of it, thou wouldest counsel us to fight for it with axes as well as

spears!”

So when Alexander King of Macedon came to

Athens with a proposal from Xerxes that in return for an alliance with them he

would grant the Athenians new territories to dwell in free, and would rebuild

the temples he had burned; and when the Spartan envoys had pleaded with them to

do no such thing as the King proposed, the Athenians made reply. We know as

well as thou that the might of the Persian is many times greater than ours, so

that thou needest not to charge us with forgetting that. Yet shall we fight for

freedom as we may. To make terms with the Barbarian seek not thou to persuade

us, nor shall we be persuaded. And now tell Mardonios that Athens says : “So

long as the sun keeps the path where now he goeth, never shall we make compact

with Xerxes; but shall go forth to do battle with him, putting our trust in the

gods that fight for us and in the mighty dead, whose dwelling-places and holy

things he hath contemned and burned with fire”.

This was their answer to Alexander; but to the

Spartans they said:

“The prayer of Sparta that we make not

agreement with the Barbarian was altogether pardonable. Yet, knowing the temper

of Athens, surely ye dishonour us by your fears, seeing that there is not so

much gold in all the world, nor any land greatly exceeding in beauty and

goodness, for which we would consent to join the Mede for the enslaving of

Hellas. Nay even if we should wish it, there be many things preventing us :

first and most, the images and shrines of the gods burned and cast upon an

heap, whom we must needs avenge to the utmost rather than be consenting with

the doer of those things; and, in the second place, there is our Greek blood

and speech, the bond of common temples and sacrifices and like ways of life, if

Athens betrayed these things, it would not be well”.

When I was writing about Greek simplicity I

should have remembered this passage. But our present theme is the meaning of

Eleutheria. “Our first duty”, say the Athenians, “is to avenge our gods and

heroes, whose temples have been desecrated”. Such language must ring strangely

in our ears until we have reflected a good deal about the character of ancient

religion. To the Greeks of Xerxes’ day religion meant, in a roughly

comprehensive phrase, the consecration of the citizen to the service of the

State. When the Athenians speak of the gods and heroes, whose temples have been

burned, they are thinking of the gods and heroes of Athens, which had been

sacked by the armies of Mardonios; and they are thinking chiefly of Athena and

Erechtheus.

Now who was Athena? You may read in books that

she was “the patron-goddess of Athens”. But she was more than that; she was

Athens. You may read that she “represented the fortune of Athens”; but indeed

she was the fortune of Athens. You may further read that she “embodied the

Athenian ideal”; which is true enough, but how small a portion of the truth! It

was not so much what Athens might become, as what Athens was, that moulded and

impassioned the image of the goddess. It was the city of today and yesterday that

filled the hearts of those Athenians with such a sense of loss and such a need

to avenge their Lady of the Acropolis. For that which had been the focus of the

old city-life, the dear familiar temple of their goddess, was a heap of stones

and ashes mixed with the carrion of the old men who had remained to die there.

As for Erechtheus, he was the great Athenian

hero. The true nature of a “hero” is an immensely controversial matter; but

what we are concerned with here is the practical question, what the ancients

thought. They, rightly or wrongly, normally thought of their “heroes” as famous

ancestors. It was as their chief ancestor that the Athenians regarded and

worshipped Erechtheus. Cecrops was earlier, but for some reason not so

worshipful; Theseus was more famous, but later, and even something of an alien,

since he appears to come originally from Troezen. Thus it was chiefly about

Erechtheus as “the father of his people”, rather than about maiden Athena, that

all that sentiment, so intense in ancient communities, of the common blood and

its sacred obligations entwined itself. This old king of primeval Athens

claimed his share of the piety due to the dead of every household, an emotion

of so powerful a quality among the unsophisticated peoples that some have

sought in it the roots of all religion. It is an emotion hard to describe and

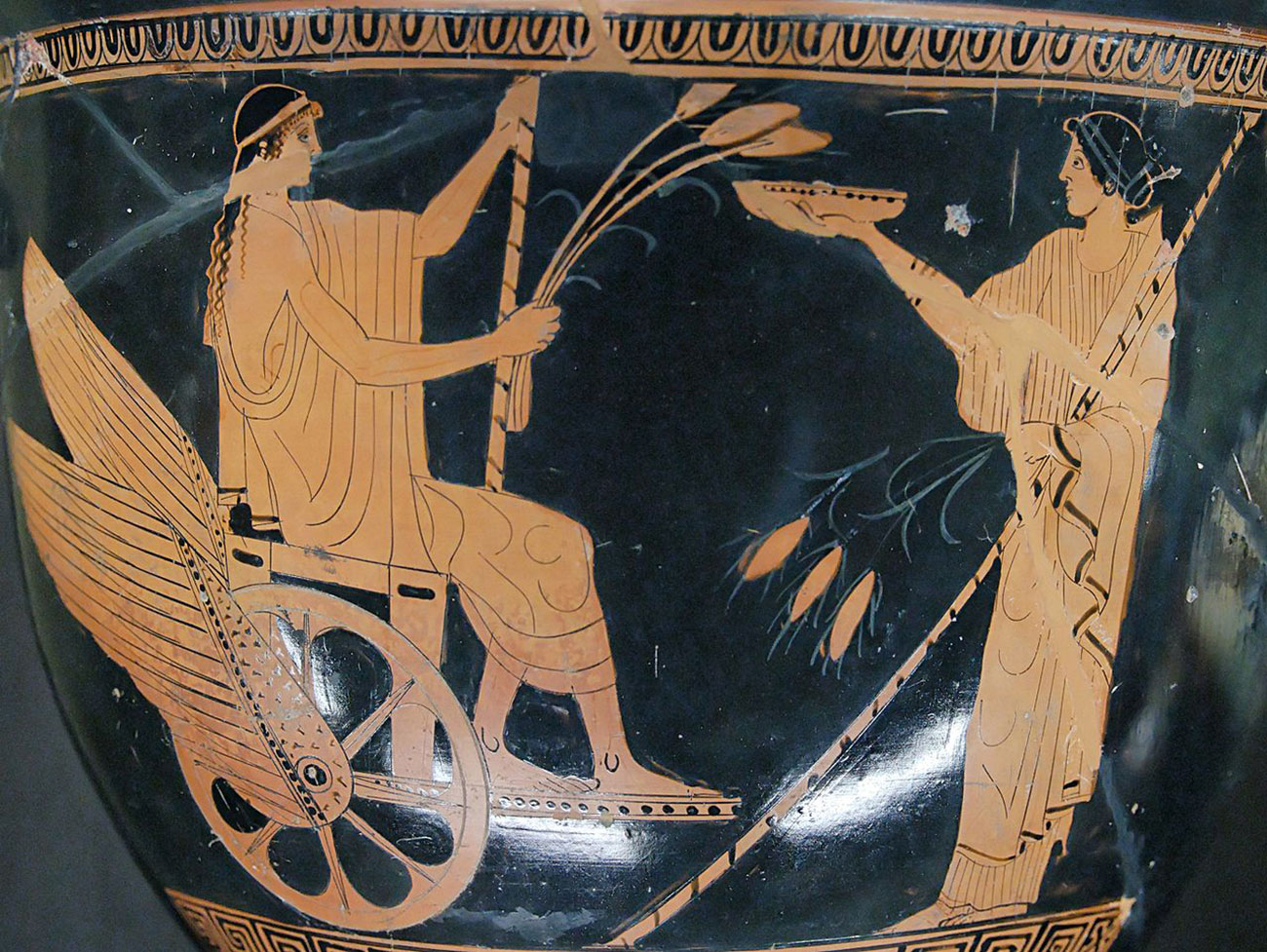

harder still to appreciate. Erechtheus was the Son of Earth, that is, really,

of Attic Earth; and on the painted vases you see him, a little naked child,

being received by Athena from the hands of Earth, a female form half hidden in

the ground, who is raising him into the light of day. The effect of all this

was to remind the Athenians that they themselves were autochthones, born

of the soil, and Attic Earth was their mother also. Not only her spiritual

children, you understand, nor only fed of her bounty, but very bone of her bone

and flesh of her flesh. Ge Kourotrophos they called her, “Earth the

Nurturer of our Children”. Unite all these feelings, rooted and made strong by time

: love of the City (Athena), love of the native and mother Earth (G), love of

the unforgotten and unforgetting dead (Erechtheus) unite all these feelings and

you will know why the defence of so great sanctities and the avenging of insult

against them seemed to Athenians the first and greatest part of Liberty.

So Themistocles felt when after Salamis he said

: “It is not we who have wrought this deed, but the gods and heroes, who hated

that one man should become lord both of Europe and of Asia; unholy and sinful,

who held things sacred and things profane in like account, burning temples and

casting down the images of the gods; who also scourged the sea and cast fetters

upon it”.

And it is this feeling which gives so singular

a beauty and charm to the story of Dikaios.

Dikaios the son of Theokydes, an Athenian then

in exile and held in reputation among the Persians, said that at this time,

when Attica was being wasted by the footmen of Xerxes and was empty of its

inhabitants, it befell that he was with Demaratos in the Thriasian Plain, when

they espied a pillar of dust, such as thirty thousand men might raise, moving

from Eleusis. And as they marvelled what men might be the cause of the dust,

presently they heard the sound of voices, and it seemed to him that it was the

ritual-chant to Iacchus. Demaratos was ignorant of the rites that are performed

at Eleusis, and questioned him what sound was that. But he said, “Demaratos, of

a certainty some great harm will befall the host of the King. For this is manifest,

there being no man left in Attica, that these are immortal Voices proceeding

from Eleusis to take vengeance for the Athenians and their allies. And if this

wrathful thing descend on Peloponnese, the King himself and his land army will

be in jeopardy; but if it turn towards the ships at Salamis, the King will be

in danger of losing his fleet. This is that festival which the Athenians hold

yearly in honour of the Mother and the Maid, and every Athenian, or other Greek

that desires it, receives initiation; and the sound thou hearest is the

chanting of the initiates”.

Demaratos answered, “Hold thy peace, and tell

no man else this tale. For if these thy words be reported to the King, thou

wilt lose thine head, and I shall not be able to save thee, I nor any other

man. But keep quiet and God will deal with this host”. Thus did he counsel him.

And the dust and the cry became a cloud, and the cloud arose and moved towards

Salamis to the encampment of the Greeks. So they knew that the navy of Xerxes

was doomed.

Athena, the Mother-Maid Demeter-Persephone with

the mystic child Iacchus, Boreas “the son-in-law of Erechtheus”, whose breath

dispersed the enemy ships under Pelion and Kaphareus of such sort are “the gods

who fight for us” and claim the love and service of Athens in return. It is

well to remember attentively this religious element in ancient patriotism, so

large an element that one may say with scarcely any exaggeration at all that

for the ancients patriotism was a religion. Therefore is Eleutheria, the patriot’s

ideal, a religion too. Such instincts and beliefs are interwoven in one sacred

indissoluble bond uniting the Gods and men, the very hills and rivers of Greece

against the foreign master. Call this if you will a mystical and confused

emotion; but do not deny its beauty or underestimate its tremendous force.

But here (lest in discussing a sentiment which

may be thought confused we ourselves fall into confusion) let us emphasize a

distinction, which has indeed been already indicated. Greek patriotism was as

wide as Greece; but on the other hand its intensity was in inverse ratio to its

extension. Greek patriotism was primarily a local thing, and it needed the

pressure of a manifest national danger to lift it to a wider outlook. That was

true in the main and of the average man, although every generation produced

certain superior spirits, statesmen or philosophers, whose thought was not

particularist. It was this home-savour which gave to ancient patriotism its

special salt and pungency. When the Athenians in the speech I quoted say that

their first duty is to avenge their gods, they are thinking more of Athens than

of Greece. They are thinking of all we mean by “home”, save that home for them

was bounded by the ring-wall of the city, not by the four walls of a house.

The wider patriotism of the nation the Greeks

openly or in their hearts ranked in the second place. Look again at the speech

of the Athenians. First came Athens and her gods and heroes their fathers’

gods; next To Hellenikon, that whereby they are not merely Athenians but

Hellenes community of race and speech, the common interest in the national gods

and their festivals, such as Zeus of Olympia with the Olympian Games, the

Delphian Apollo with the Pythian Games. Of course this Hellenic or Panhellenic

interest was always there, and in a sense the future lay with it; but never in

the times when Greece was at its greatest did it supplant the old intense local

loyalties. The movement of Greek civilization is from the narrower to the

larger conception of patriotism, but the latter ideal is grounded in the

former. Greek love of country was fed from local fires, and even Greek

cosmopolitanism left one a citizen, albeit a citizen of the world. So it was

with Eleutheria, which enlarged itself in the same sense and with an equal

pace.

This development can be studied best in Athens,

which was “the Hellas of Hellas”. One finds in Attic literature a passionate

Hellenism combined with a passionate conviction that Hellenism finds its best

representative in Athens. The old local patriotism survives, but is nourished

more and more with new ambitions. New claims, new ideals are advanced. One

claim appears very early, if we may believe Herodotus that the Athenians used

it in debate with the men of Tegea before the Battle of Plataea. The Athenians

recalled how they had given shelter to the Children of Heracles when all the

other Greek cities would not, for fear of Eurystheus; and how again they had

rescued the slain of the Seven from the Theban king and buried them in his

despite. On those two famous occasions the Athenians had shown the virtue which

they held to be most characteristic of Hellenism and especially native to

themselves, the virtue which they called "philanthropy" or the love

of man. What Heine said of himself, the Athenians might have said: they were

brave soldiers in the liberation-war of humanity.

There is a play of Euripides, called The

Suppliant Women, which deals with the episode of the unburied dead at

Thebes. The fragmentary Argument says: The scene is Eleusis. Chorus of

Argive women, mothers of the champions who have fallen at Thebes. The drama is

a glorification of Athens. The eloquent Adrastos, king of Argos, pleads the

cause of the suppliant women who have come to Athens to beg the aid of its young

king Theseus in procuring the burial of their dead. Theseus is at first

disposed to reject their prayer, for reasons of State; he must consider the

safety of his own people; when his mother Aithra breaks out indignantly.

“Surely it will be said that with unvalorous hands, when thou mightest have won

a crown of glory for thy city, thou didst decline the peril and match thyself,

ignoble labour, with a savage swine; and when it was thy part to look to helm

and spear, putting forth thy might therein, wast proven a coward. To think that

son of mine ah, do not so! Seest thou how Athens, whom mocking lips have named

unwise, flashes back upon her scorners a glance of answering scorn? Danger is

her element. It is the unadventurous cities doing cautious things in the dark,

whose vision is thereby also darkened”. And the result is that Theseus and his

men set out against the great power of Thebes, defeat it and recover the

bodies, which with due observance of the appropriate rites they inter in Attic

earth.

“To make the world safe for democracy” is

something; but Athens never found it safe, perhaps did not believe it could be

safe. Ready to take risks, facing danger with a lifting of the heart ... their

whole life a round of toils and dangers ... born neither themselves to rest nor

to let other people. In such phrases are the Athenians described by their

enemies.

A friend has said: “I must publish an opinion

which will be displeasing to most; yet (since I think it to be true) I will not

withhold it. If the Athenians in fear of the coming peril had left their land,

or not leaving it but staying behind had yielded themselves to Xerxes, none

would have tried to meet the King at sea”. And so all would have been lost.

“But as the matter fell out, it would be the simple truth to say that the

Athenians were the saviours of Greece. The balance of success was certain to

turn to the side they espoused, and by choosing the cause of Hellas and the

preservation of her freedom it was the Athenians and no other that roused the whole

Greek world save those who played the traitor and under God thrust back the

King”. And some generations later, Demosthenes, in what might be called the

funeral oration of Eleutheria, sums up the claim of Athens in words whose

undying splendour is all pride and glory transfiguring the pain of failure and

defeat.

“Let no man, I beseech you, imagine that there

is anything of paradox or exaggeration in what I say, but sympathetically

consider it. If the event had been clear to all men beforehand ... even then

Athens could only have done what she did, if her fame and her future and the

opinion of ages to come meant anything to her. For the moment indeed it looks

as if she had failed; as man must always fail when God so wills it. But had

She, who claimed to be the leader of Greece, yielded her claim to Philip and

betrayed the common cause, her honour would not be clear ... Yes, men of

Athens, ye did right be very sure of that when ye adventured yourselves for the

safety and freedom of all; yes, by your fathers who fought at Marathon and

Plataea and Salamis and Artemision, and many more lying in their tombs of

public honour they had deserved so well, being all alike deemed worthy of this

equal tribute by the State, and not only (0 Aeschines) the successful, the victorious

...”

Demosthenes was right in thinking that

Eleutheria was most at home in Athens. Now Athens, as all men know, was a

“democracy”; that is, the general body of the citizens (excluding the slaves

and “resident aliens”) personally made and interpreted their laws. Such a

constitution was characterized by two elements which between them practically

exhausted its meaning; namely, autonomy or freedom to govern oneself by

one's own laws, and isonomy or equality of all citizens before the law.

Thus Eleutheria, denned as the Reign of Law, may be regarded as synonymous with

Democracy. “The basis of the democratical constitution is Eleutheria”, says

Aristotle. This is common ground with all Greek writers, whether they write to

praise or to condemn. Thus Plato humorously, but not quite good-humouredly,

complains that in Athens the very horses and donkeys knocked you out of their

way, so exhilarated were they by the atmosphere of Eleutheria. But at the worst

he only means that you may have too much of a good thing. Eleutheria translated

as unlimited democracy you may object to; Eleutheria as an ideal or a watchword

never fails to win the homage of Greek men. Very early begins that sentimental

republicanism which is the inspiration of Plutarch, and through Plutarch has

had so vast an influence on the practical affairs of mankind. It appears in the

famous drinking-catch beginning “I will bear the sword in the myrtle-branch

like Harmodios and Aristogeiton”. It appears in Herodotus. Otanes the Persian

(talking Greek political philosophy), after recounting all the evils of a

tyrant's reign, is made to say : “But what I am about to tell are his greatest

crimes : he breaks ancestral customs, and forces women, and puts men to death

without trial”. But the rule of the people in the first place has the fairest

name in the world, “isonomy”, and in the second place it does none of those

things a despot doeth. In his own person Herodotus writes. “It is clear not

merely in one but in every instance how excellent a thing is equality”. When the Athenians were under their tyrants they fought no better than their

neighbours, but after they had got rid of their masters they were easily

superior. Now this proves that when they were held down they fought without

spirit, because they were toiling for a master, but when they had been

liberated every man was stimulated to his utmost efforts in his own behalf. The

same morning confidence in democracy shines in the reply of the constitutional

king, Theseus, too to the herald in Euripides’ play asking for the “tyrant” of

Athens. “You have made a false step in the beginning of your speech, stranger,

in seeking a tyrant here. Athens is not ruled by one man, but is free. The

people govern by turns in yearly succession, not favouring the rich but giving

him equal measure with the poor”.

The naiveté of this provokes a smile, but it

should provoke some reflection too. Why does the rhetoric of liberty move us so

little? Partly, I think, because the meaning of the word has changed, and

partly because of this new “liberty” we have a super-abundance. No longer does

Liberty mean in the first place the Reign of Law, but something like its

opposite. Let us recover the Greek attitude, and we recapture, or at least

understand, the Greek emotion concerning Eleutheria. Jason says to Medea in

Euripides’ play, “Thou dwellest in a Greek instead, of a Barbarian land, and

hast come to know Justice and the use of Law without favour to the strong”. The

most “romantic” hero in Greek legend recommending the conventions!

This, however, is admirably and

characteristically Greek. The typical heroes of ancient story are alike in

their championship of law and order. I suppose the two most popular and

representative were Heracles and Theseus. Each goes up and down Greece and Barbary

destroying hybristai, local robber-kings, strong savages, devouring monsters,

ill customs and every manner of “lawlessness” and “injustice”. In their place

each introduces Greek manners and government, Law and Justice. It was this

which so attracted Greek sympathy to them and so excited the Greek imagination.

For the Greeks were surrounded by dangers like those which Heracles or Theseus

encountered. If they had not to contend with supernatural hydras and

triple-bodied giants and half-human animals, they had endless pioneering work

to do which made such imaginings real enough to them; and men who had fought

with the wild Thracian tribes could vividly sympathize with Heracles in his

battle with the Thracian “king”, Diomedes, who fed his fire-breathing horses

with the flesh of strangers. Nor was this preference of the Greeks for heroes

of such a type merely instinctive; it was reasoned and conscious. The “mission”

of Heracles, for example, is largely the theme of Euripides’ play which we

usually call Hercules Furens. A contemporary of Euripides, the sophist

Hippias of Elis, was the author of a too famous apologue, The Choice of

Heracles, representing the youthful hero making the correct choice between

Laborious Virtue and Luxurious Vice.

Another Euripidean play, The Suppliant Women,

as we have seen, reveals Theseus in the character of a conventional, almost

painfully constitutional, sovereign talking the language of Lord John Russell.

As for us, our sympathies are ready to flow out to the picturesque defeated

monsters, the free Centaurs galloping on Pelion, the cannibal Minotaur lurking

in his Labyrinth. But then our bridals are not liable to be disturbed by raids

of wild horsemen from the mountains, nor are our children carried off to be

dealt with at the pleasure of a foreign monarch. People who meet with such

experiences get surprisingly tired of them. There is a figure known to

mythologists as a Culture Hero. He it is who is believed to have introduced law

and order and useful arts into the rude com- munity in which he arose. Such

heroes were specially regarded, and the reverence felt for them measures the

need of them. Thus in ancient Greece we read of Prometheus and Palamedes, the

Finns had their Wainomoinen, the Indians of North America their Hiawatha. Think

again of historical figures like Charlemagne and Alfred, like Solon and Numa

Pompilius, even Alexander the Great. A peculiar romance clings about their

names. Why? Only because to people fighting what must often have seemed a

losing battle against chaos and night the institution and defence of law and

order seemed the most romantic thing a man could do. And so it was.

Such a view was natural for them. Whether it

shall seem natural to us depends on the fortunes of our civilization. On that

subject we may leave the prophets to rave, and content ourselves with the

observation that there are parts of Europe today in which many a man must feel

himself in the position of Roland fighting the Saracens or Aetius against the

Huns. As for ourselves, how-ever confident we may feel, we shall be foolish to

be over-confident; for we are fighting a battle that has no end. The Barbarian

we shall have always with us, on our frontiers or in our own breasts. There is

also the danger that the prize of victory may, like Angelica, escape the

strivers' hands. Already perhaps the vision which inspires us is changing. I am

not concerned to attack the character of that change but to interpret the Greek

conception of civilization, merely as a contribution to the problem. To the Greeks,

then, civilization is the slow result of a certain immemorial way of living.

You cannot get it up from books, or acquire it by imitation; you must absorb it

and let it form your spirit, you must live in it and live through it; and it

will be hard for you to do this, unless you have been born into it and received

it as a birth-right, as a mould in which you are cast as your fathers were.

“Oh, but we must be more progressive than that”. Well, we are not; on the

contrary the Greeks were very much the most progressive people that ever

existed intellectually progressive, I mean of course; for are we not talking

about civilization?

The Greek conception, therefore, seems to work.

I think it works, and worked, because the tradition, so cherished as it is, is not

regarded as stationary. It is no more stationary to the Greeks than a tree, and

a tree whose growth they stimulated in every way. It seems a fairly common

error, into which Mr. Belloc and Mr. Chesterton sometimes fall, for modern

champions of tradition to over-emphasize its stability. There has always been

the type of “vinous, loudly singing, unsanitary men”, which Mr. Wells has

called the ideal of these two writers; he is the foundational type of European

civilization. But it almost looks as if Mr. Belloc and Mr. Chesterton were

entirely satisfied with him. They want him to stay on his small holding, and

eat quantities of ham and cheese, and drink quarts of ale, and hate rich men

and politicians, and be perfectly parochial and illiterate. But Hellenism means,

simply an effort to work on this sound and solid stuff ; it is not content to

leave him as he is; it strives to develop him, but to develop him within 1 the

tradition; to transform him from an Aristophanic demes-man into an Athenian

citizen. But Mr. Belloc and Mr. Chesterton are Greek in this, that they have

constantly the sense of fighting an endless and doubtful battle against strong

enemies that would destroy whatever is most necessary to the soul of civilized

men. Well I know in my heart and soul that sacred Ilium must fall, and

Priam, and the folk of Priam with the good ashen spear . . . yet before I die

will I do a deed for after ages to hear of!

We, like the Greeks, are apt to speak in our

loose way of the Asiatic or the “Oriental,” reflecting on his servility, his

patience, his reserve. But in so doing we lose sight of that other element in

the East which presents in many ways the exact opposite of these

characteristics. Before men had formed those larger groups which are essential

to civilization they lived in smaller groups or tribes, and after the larger

groups had been formed the tribal system in mountain and desert went on as

before. We can still see in the East today many peoples who have not emerged

from this stage.

The men of these primitive tribes are free. And

the reason is plain. In proportion to the smallness of the group the individual

has greater influence. Where the whole community can meet for discussion, the

general sense is articulate and compulsive. The chronic wars between clan and

clan make all the men fighters from their youth up. On the other hand

civilization is promoted by every widening of intercourse, everything which

fuses the isolated tribal groups, which resolves them in a larger body. The

loss of freedom was the price which had to be paid for civilization.

It was in the great alluvial plains, where

there are few natural barriers and a kind soil made life easy, along the Nile

and the Euphrates, that men first coalesced in larger combinations, exchanging

their old turbulent freedom for a life of peace and labour under the laws of a

common master. The Egyptians and Babylonians had already reached the stage of

civilization and despotism at the first dawn of history. But in the case of

others a record of the transition remains. The example of the great kings who

ruled on the Nile and the Euphrates set up a mark for the ambition of strong

men among the neighbouring tribes. The military power which resulted from the

gathering of much people under one hand showed the tribes the uses of

combination. Lesser kingdoms grew up in other lands with courts which copied

those of Memphis and Babylon on a smaller scale.

The moment of transition is depicted for us in

the case of Israel. Here we see the advantages of the tribal and the monarchical

system deliberately weighed in the assembly of the people. On the one hand

there is the great gain in order and military efficiency promised by a

concentration of power: “We will have a king over us; that we also may be like

all the nations; and that our king may judge us, and go out before us, and

fight our battles.” On the other hand there is the sacrifice entailed upon the

people by the compulsion to maintain a court, the tribute of body-service and

property, the loss, in fact, of liberty.

By the time that Hellenism had reached its full

development the East, as far as the Greeks knew it, was united under an Iranian

Great King. The Iranian Empire had swallowed up the preceding Semitic and

Egyptian Empires, and in the vast reach of the territory which the Persian king

ruled in the fifth century before Christ he exceeded any potentate that this

world had yet seen. He seemed to the Greeks to have touched the pinnacle of

human greatness. And yet monarchy was a comparatively new thing among the

Iranians. The time when they were still in the tribal stage was within memory.

Even now the old tribal organization in Iran wan not done away; it was simply

overshadowed by the preeminent power attained by the house of Achaemenes,

whose conquests beyond the limits of Iran had given it the absolute disposal of

vast populations. Tradition, reproduced for us by Herodotus, still spoke of the

beginnings of kingship in Iran. The main features of that story are probably

true; the ambition excited in Deioces the Mede after his people had freed

themselves from the yoke of Assyria; the weariness of their intestine feuds,

which made the Medes acquiesce in common subjection to one great man; the

strangeness of the innovation when a Mede surrounded himself with the pomp and

circumstance which imitated the court of Nineveh. After the False Smerdis was

overthrown it was even seriously debated, Herodotus assures us, by the heads of

the Persian clans, whether it would not be a good thing to abolish the kingship

and choose, some form of association more consonant with ancestral customs, in

which the tribal chiefs or the tribal assemblies should be the ruling

authority.

As an alternative, then, to the rude freedom of

primitive tribes, the world, up to the appearance of Hellenism, seemed to

present only unprogressive despotism. Some of the nations, like the Egyptians

and Babylonians, had been subject to kings for thousands of years. And during

all that time there had been no advance. Movement there had been, dynastic

revolutions, foreign conquests, changes of fashion in dress, in art, in

religion, but no progress. If anything there had been decline. Between the king

and his subjects the relation was that of master and slave. The royal officials

were the king’s creatures, responsible to him, not to the people. He had at his

command an army which gave him transcendent material power. Upon the people he

made two main demands, and they on their part expected two main things from

him. He took firstly their persons, when he chose, for his service, and

secondly as much of their property as he thought good. And what they asked of

him in return was firstly external peace, since he alone by his army could

repel the foreign invader or the wild tribes of hill and desert, and secondly

internal peace, which he secured by being, himself or through his deputies, the

judge of their disputes.

It was under these circumstances that the

character we now describe as “Oriental” was developed. To the husbandman or

merchant it never occurred that the work of government was any concern of his;

he was merely a unit in a great aggregate, whose sole bond of union was its

subjection to one external authority; for him, while kings went to war, it was

enough to make provision for himself and his children in this life, or make

sure of good things in the next, and let the world take its way. It was not to

be wondered at that he came to find the world uninteresting outside his own

concerns—his bodily wants and his religion. He had to submit perforce to

whatever violences or exactions the king or his ministers chose to put upon

him; he had no defense but concealment; and he developed the bravery, not of

action, but of endurance, and an extraordinary secretiveness. He became the

Oriental whom we know.

Then with the appearance of Hellenism

twenty-five centuries ago there was a new thing in the earth. The Greeks did

not find themselves shut up to the alternative of tribal rudeness or cultured

despotism. They passed from the tribal stage to a form of association which was

neither the one nor the other—the city-state. They were not absolutely the first

to develop the city-state; they had been preceded by the Semites of Syria.

Before Athens and Sparta were heard of, Tyre and Sidon had spread their name

over the Mediterranean. But it was not till the city-state entered into

combination with the peculiar endowments of the Hellenes that it produced a new

and wonderful form of culture.

The race among whom the city-state bore this

fruit was not spread over rich plains, like those in which the older

civilizations had their seat. It was broken into a hundred fragments and

distributed among mountain valleys and islands. These natural divisions tended

to withhold its groups from fusion, whilst the sea, which ran in upon it

everywhere, in long creeks and bays, invited it to intercourse and enterprise.

Under these circumstances the original tribal villages grouped themselves upon

centres which constituted cities. For so large a number of men to enter upon so

close cooperation as the city-state implied had not been possible under the old

tribal system. But their doing so was a pre-requisite for that elaboration of

life which we call civilized. At the same time the city was not too large for

the general voice of its members to find collective expression. It was a true

instinct which led the Greek republics to be above all things jealous of their

independence to fret at any restraint by which their separate, sovereignty was

sacrificed in some larger combination.

Hellenism, as that culture may most conveniently

be called, was the product of the Greek city-state. How far it was due, to the

natural aptitudes of the Greeks, and how far to the form of political

association under which they lived, need not now be discussed. It will be

enough to indicate the real connection between the form of the Greek state anti

the characteristics which made Hellenism different from any civilization which

before had been.

We may discern in Hellenism a moral and an

intellectual side; it implied a certain type of character, and it

implied a certain cast of ideas. It was of the former that the Greek was

thinking when he distinguished himself as a free man from the barbarian. The

authority he obeyed was not an external one. He had grown up with the

consciousness of being the member of a free state, a state in which he had an

individual value, a share in the sovereignty. This gave him a self-respect

strange to those Orientals whom he smiled to see crawling prostrate before the

thrones of their kings. It gave him an energy of will, a power of initiative

impossible to a unit of those driven multitudes. It gave his speech a

directness and simplicity which disdained courtly circumlocutions and

exaggerations. It gave his manners a striking naturalness and absence of

constraint.

But he was the member of a state.

Freedom meant for him nothing which approached the exemption of the individual

from his obligations to, and control by, the community. The life of the Greek

citizen was dominated by his duty to the state. The state claimed him, body and

spirit, and enforced its claims, not so much by external rewards and penalties,

as by implanting its ideals in his soul, by fostering a sense of honour and a

sense of obligation. Corruption and venality have always been the rule in

governments of the Oriental pattern. The idea of the state as an object of

devotion, operating on the main body of citizens and in the secret passages of

their lives—this was a new thing in the Greek republics. It was this which gave

force to the laws and savour to the public debates. It was this as much as his

personal courage which made the citizen-soldier obey cheerfully and die

collectedly in his place. It is easy to point to lapses from this ideal in the

public men of ancient Greece; even Miltiades, Themistocles, and Demosthenes had

not always clean hands. But no one would contend that the moral qualities which

the free state tended to produce were universal among the Greeks or wholly

absent among the barbarians. It is a question of degree. Without a higher

standard of public honesty, a more cogent sense of public duty than an Oriental

state can show, the free institutions of Greece could not have worked for a

month.

The Hellenic character no sooner attained

distinct being than the Greek attracted the attention of the older peoples as a

force to be reckoned with. Kings became aware that a unique race of soldiers,

upon which they could draw, had appeared. In fact, the first obvious

consequence of the union of independence and discipline in the Greek, as it

affected the rest of the world, was to make him the military superior of the

men of other nations. At the very dawn of Greek history, in the seventh century

B.C., Pharaoh Necho employed Greek mercenaries, and in recognition of their

services (perhaps on that field where King Josiah of Judah fell) dedicated his

corslet at a Greek shrine. The brother of the poet Alcaeus won

distinction in the army of the king of Babylon. Under the later Egyptian kings

the corps of Greek mercenaries counted for much more than the native levies. The

Persian conquest, which overspread Western Asia in the latter part of the sixth

century and the beginning of the fifth, was checked on Greek soil, and the

armies of the Great King rolled back with appalling disaster. By the end of the

century the Persians had come, like the Egyptians, to place their main reliance

on Greek mercenaries. The superiority of the Greeks was displayed openly by the

Ten Thousand and the campaigns of Agesilaus. From this time it was clear that

if the Hellenic race could concentrate its forces in any political union it

might rule the world.

Besides a certain type of character, a new

intellectual type was presented by the Greeks. The imagination of the Greeks

was perhaps not richer, their feeling not more intense than that of other

peoples—in the religious sentiment, for instance, we might even say the Greek

stood behind the Oriental; but the imagination and feeling of the Greeks were

more strictly regulated. The Greek made a notable advance in seeing the world

about him as it really was. He wanted to understand it as a rational whole. The

distinguishing characteristic which marks all the manifestations of his mind,

in politics, in philosophy, in art, is his critical faculty, his rationalism,

or, to put the same thing in another way, his bent of referring things to the

standard of reason and reality. He was far more circumspect than the Oriental

in verifying his impressions. He could not always take a traditional opinion or

custom for granted and rest satisfied with the declaration, “So it was from the

beginning,’' or “Such was the manner of our fathers.” His mind was the more

emancipated from the tyranny of custom that it might be the more subjected to

the guidance of truth.

And here again we may see the influence of his

political environment. There is nothing in a despotism to quicken thought; the

obedience demanded is unreasoning; the principles of government are locked in

the king’s breast. In a Greek city it was far otherwise. In the democracies

especially the citizens were all their lives accustomed to have alternative

policies laid before them in the Assembly, to listen to the pleadings in the

law-courts, to follow opposed arguments. What one moment appeared true was

presently probed and convicted of fallacy. Institutions were justified or

impugned by reference to the large principles of the Beautiful or the

Profitable. The Greek lived in an atmosphere of debate; the market-place was a

school of gymnastic for the critical faculty. Plato could only conceive of the

reasoning process as a dialogue.

Under these circumstances, in spite of the natural

reverence for accepted custom and belief, in spite of the opposition of the

more conservative tempers —an opposition which we still hear grumbling

throughout Greek literature— the critical faculty came increasingly into play.

It came into all spheres of activity as an abiding principle of progress. Of

progress, as opposed to stagnation, because it held the established on its

trial; of progress, as opposed to random movement, because it regulated the

course of innovation. The state, in which this faculty operates, shows the

characteristic of a living organism, continuous modification according to

environment.

The critical faculty, the reason—in one light

it appears as the sense of proportion; the sense of proportion in

politics, “common sense,” balance of judgment; the sense of proportion in

behavior, which distinguishes what is seemly for the occasion and the person

concerned; the sense of proportion in art, which eliminates the redundant and

keeps each detail in its due subordination to the whole. How prominent this

aspect of the critical faculty was with the Greeks their language itself shows; reason and proportion are expressed by a common word. “The Hellenes”

Polybius says, “differ mainly in this respect from other men, that they keep to

what is due in each case.” “Nothing in excess,” is the most characteristic

piece of Hellenic wisdom.

We have arrived at this, that the distinctive

quality of the Hellenic mind is a rationalism, which on one side of it is a

grasp of the real world, and on another side a sense of proportion. How true

this is in the sphere of art, literary or plastic, no one acquainted with

either needs to be told. We can measure the bound forward made in human history

by the Greeks between twenty and twenty-five centuries ago if we compare an

Attic tragedy with the dreary verbiage of the Avesta or the relics of Egyptian

literature recovered from temple and tomb. Or contrast the Parthenon, a single

thought in stone, a living unity exquisitely adjusted in all its parts, with

the unintelligent piles of the Egyptians, mechanically uniform, impressive from

bulk, from superficial ornaments and the indescribable charm of the Nile

landscape.

But notable as were the achievements of the

Greeks in the sphere of art, still more momentous for mankind was the impulse

they gave to science. With them a broader daylight began to play upon all the

relations of human life and the appearances of nature. They submitted man and

the world to a more systematic investigation, they thought more methodically,

more sanely, about things than any people had done before them. In process of

doing so they brought into currency a large number of new ideas, of new canons

of judgment, embodied in systems of philosophy, in floating theories, in the

ordinary language of the street. The systems of philosophy were, of course, as

systems, provisional, inadequate, and full of crudities; each of them had

ultimately to be discarded by mankind; but many of the ideas which made up

their fabric, much of the material, so to speak, used in their construction,

survived as of permanent value, and was available for sounder combinations

hereafter. And secondly, besides a body of permanently valid ideas which

represented the finished product of the Greek method of inquiry, the Greeks

transmitted that method itself to the world. We can see today that the method,

in the form to which the Greeks brought it, was as imperfect as the results it

yielded. But it was nevertheless an advance on anything which had gone before.

The Greek stood far behind the modern scientific inquirer in his comprehension

of the means to extort her secrets from Nature, but he arrived at a juster

conception of reasoning, he dealt more soberly with evidence, than it had been

within the power of mankind up till his time to do. And, imperfect as the

method was, it contained within itself the means for its own improvement. Men

once set thinking on the right lines would carry the process farther and

farther. Hellenism was great in its potency; in its promise it was far greater.

We have attempted to explain what we mean by

Hellenism, to place in a clear light what distinguished the civilization

developed in the city-republics of the Greeks between the tenth and fourth centuries

before Christ from all that the world had yet known. It remains to consider

what the fortunes of that civilization, once introduced into the world, had

been. It had been developed by the city-state in virtue of certain qualities

which this form of association possessed, but which were not possessed by the

Oriental despotisms—comparative restriction of size, internal liberty, and the

habit of free discussion. But by the fourth century before Christ it had become

apparent that these very qualities carried with them grave defects. The

bitterness of faction in these free cities reached often appalling lengths and

led to terrible atrocities. Almost everywhere the energies of the race were

frittered in perpetual discord. The critical faculty itself began to work

destructively upon the institutions which had generated it. The imperfections

of the small state were increasingly exposed, and yet the smallness appeared

necessary to freedom. Also the Greeks now suffered for their backwardness in

the matter of religion. The Jews were left at the fall of their state still in presence

of a living God, who claimed their allegiance; the Greek religion was so

damaged by the play of criticism that at the decay of civic morality the Greeks

had no adequate religious tradition to fall back upon.

Again, the separation of the race into a number

of small states, while it had produced an incomparable soldiery, prevented the

formation of a great military power. It was in vain that idealists preached an

allied attack of all the Greeks upon the great barbarian empire which neighboured

them on the east. The Persian king had nothing serious to fear from the Greek

states; each of them was ready enough to take his gold in order to use it

against its rivals, and the dreaded soldiery he enrolled by masses in his own

armies.

It was in the union of a great force under a

single control that Oriental monarchy was strong. Could Hellenism remedy the

defects of disunion by entering into some alliance with the monarchic

principle? Would it be untrue to itself in doing so? What price would it have

to pay for worldly supremacy? These problems confronted Greek politicians in a

concrete form when, in the fourth century before Christ, Macedonia entered as a new power upon

the scene.

Macedonia was a monarchic state, but not one of

the same class as the Persian Empire, or the empires which had preceded the

Persian. It belonged rather to those which have but half emerged from the

tribal stage. There had been an “heroic” monarchy of a like kind in Greece

itself, as we see it in the Homeric poems. It resembled still more closely

perhaps the old Persian kingdom, as it had been when Cyrus went forth

conquering and to conquer. The bulk of the people was formed of a vigorous

peasantry who still retained the rude virtues engendered by tribal freedom, and

showed towards the King himself an outspoken independence of carriage. The King

was but the chief of one of the great families, of one which had been raised by

earlier chiefs to a position of power and dignity above the rest. The other

houses, whose heads had once been themselves little kings, each in his own

mountain region, now formed a hereditary nobility which surrounded, and to some

extent controlled, the throne. Hut this comparative independence did not impair

the advantage, from the military point of view, which came from the

concentration of power in one hand. When the King resolved to go to war he

could call out the whole ban of the kingdom, and his people were bound to obey

his summons. The nobles came to the field on horse, his “Companions” they were

called; the peasantry on foot, his “Foot-companions”. The stout pikemen of

Macedonia saw in their King not their hereditary chief only, but a good

comrade; and the sense of this made them follow him, we may believe, with a

prouder and more cheerful loyalty in those continual marchings to and fro

across the Illyrian and Thracian hills.

Philip the Second of Macedonia, having made his

kingdom the strongest power of the Balkan peninsula, presented himself to the

Hellenes as their captain-general against barbarism. There were many

considerations to make this offer one which the Hellenes could with dignity

accept. In the first place, the Macedonians, though not actually Hellenes, were

probably close of kin, a more backward branch of the same stock. In the second

place, Hellenism itself had penetrated largely into Macedonia. Although it had

required a certain set of political conditions to produce Hellenism, a great

part of Hellenism, once developed—the body of ideas, of literary and artistic

tastes—was communicable to men who had not themselves lived under those

conditions. We find, therefore, that by the fourth century B.C. Hellenism was

already exerting influence outside its own borders. The Phoenicians of Cyprus,

for example, the Lycians and Carians were partially Hellenized. But in no

country was the Hellenic culture more predominant than in the neighbouring

Macedonia. The ruling house claimed to be of good Greek descent and traced its

pedigree to the old kings of Argos. The court was a gathering-place of Greek

literati, philosophers, artists, and adventurers. Euripides, we remember, had

ended his days there under King Archelaus. Philip, who had spent a part of his

youth as a hostage in Thebes, was well conversant with Greek language and

literature. The man in whom Greek wisdom reached its climax was engaged to form

the mind of his son. Alexander’s own ideals were drawn from the heroic poetry

of Greece. The nobility as a whole took its colour from the court; we may

suppose that Greek was generally understood among them. Their names are, with a

few exceptions, pure Greek.

Should the Hellenes accept Philip’s

terms—confederation under Macedonian suzerainty against the barbaric world? In

most of the Greek states this question, the crucial question of the day, was

answered Yes and No with great fierceness and partisan eloquence. The No has

found immortal expression in Demosthenes. But history decided for the

affirmative. Philip, who offered, had the power to compel.

So Hellenism enters on quite a new chapter of

its history. On the one hand that separate independence of the states which had

conditioned its growth was doomed; on the other hand a gigantic military power

arose, inspired by Hellenic ideas. The break-up of the Macedonian Empire at

Alexander’s death, it is true, gave a breathing space to Greek independence in

its home, and imperilled the ascendancy of Greek culture in the newly conquered

fields. But for a long time the ruling powers in the Balkan peninsula, in Asia

Minor, Egypt, Babylon, Irk, the lands of the Indus—of all those countries which

had been the seats of Aryan and Semitic civilization—-continued to be monarchic

courts, Greek in speech and mind.

Then when the Greek dynasties dwindle, when the

sceptre seems about to return to barbarian hands, Rome, the real successor of

Alexander, having itself taken all the mental and artistic culture it possesses

from the Greeks, steps in to lend the strength of its arm to maintain the

supremacy of Greek civilization in the East. India certainly is lost, Iran is

last, to Hellenism, but on this side of the Euphrates its domain is

triumphantly restored. Hellenism, however, had still to pay the price. The law

of ancient history was inexorable: a large state must be a monarchic state.

Rome in becoming a world-power became a monarchy.

This, then, is the second chapter of the history

of Hellenism: it is propagated and maintained by despotic kings, first

Macedonian, and then Roman. The result is as might have been expected. Firstly,

Hellenism is carried for beyond its original borders: the vessel is broken and

the long-secreted elixir poured out for the nations. On the other hand the

internal development of Hellenism is arrested. Death did not come all at once.

It was not till the Mediterranean countries were united under the single rule

of Rome that the Greek states lost all independence of action. Scientific

research under the patronage of kings made considerable progress for some

centuries after Alexander, now that new fields were thrown open by Macedonian

and Roman conquests to the spirit of inquiry which had been developed among the

Hellenes before their subjection. But philosophy reached no higher point after

Aristotle; the work of the later schools was mainly to popularize ideas already

reached by the few. Literature and art declined from the beginning of the

Macedonian empire, both being thenceforth concerned only with the industrious

study and reproduction of the works of a freer age, except for some late blooms

(like the artistic schools of Rhodes and Pergamum) into which the old sap ran

before it dried. Learning, laborious, mechanical, unprogressive, took the place

of creation. As for the moral side of Hellenism, we find a considerable amount

of civic patriotism subsisting for a long time both in the old Greek cities and

in the new ones which sprang up over the East. When patriotism could no longer

take the form of directing and defending the city as a sovereign state it could

still spend money and pains in works of benevolence for the body of citizens or

in making the city beautiful to see. The ruins of Greek building scattered over

Nearer Asia belong by an enormous majority to Roman times. Athens itself was

more splendid in appearance under Hadrian than under Pericles. But even this

latter-day patriotism gradually died away.

It was not only that the monarchic principle

was in itself unfavourable to the development of Greek culture. The monarchy

became more and more like those despotisms of the older world which it had

replaced. We know how quickly Alexander assumed the robe and character of the

Persian king. The earlier Roman Emperors were restrained by the traditions of

the Republic, but these became obsolete, and the court of Diocletian or of

Constantine differed nothing from the type shown by the East.

It is an early phase of this second chapter of

Hellenic history that we watch in the career of the Seleucid dynasty. By far

the largest part of Alexander’s empire was for some time under the sway of

Seleucus and his descendants, and that the part containing the seats of all the

older civilizations, except the Egyptian. It was under the aegis of the house

of Seleucus that Hellenism struck roots during the third century before Christ

in all lands from the Mediterranean to the Pamir. We see Hellenic civilization

everywhere, still embodied in city-states, but subject city-states, at issue

with the two antagonistic principles of monarchy and of barbarism, but

compelled to make a compromise with the first of these to save itself from the

second. We see the dynasty that stands for Hellenism grow weaker and more

futile, till the Romans, when they roll back the Armenian invasion from Syria,

find only a shadow of it surviving. Lastly, we can see in the organization, and

institutions of the Roman Empire much that was taken over from the Hellenistic

kingdoms which went before.

We have tried to define the significance of the

Seleucid epoch by showing the place it holds in ancient history. But we should

have gained little, if we stopped short there, if we failed to inquire in what

relation the development of ancient history in its sum stands to the modern

world of which we form part. The Hellenism of which ancient history makes

everything, developed in the city-republics of Greece, propagated by Alexander,

sustained by the Seleucids and Rome, and involved in the fall of the Roman

Empire—what has become of it in the many centuries since then?

No antithesis is more frequent in the popular

mouth today than that between East and West, between the European spirit and

the Oriental. We are familiar with the. superiority, the material supremacy, of

European civilization. When, however, we analyse this difference of the,

European, when we state what exactly the qualities are in which the Western

presents such a contrast to the Oriental, they turn out to be just those which

distinguished the ancient Hellene from the Oriental of his day. On the moral

side the citizen of the modern European state, like the citizen of the old

Greek city, is conscious of a share in the government, is distinguished from

the Oriental by a higher political morality (higher, for all its lapses), a

more manly self-reliance, and a greater power of initiative. On the

intellectual side it is the critical spirit which lies at the basis of his

political sense, of his conquests in the sphere of science, of his sober and

mighty literature, of his body of well-tested ideas, of his power of consequent

thought. And whence did the modern European derive these qualities? The moral

part of them springs in large measure from the same source as in the case of

the Greeks—political freedom; the intellectual part of them is a direct legacy

from the Greeks. What we call the Western spirit in our own day is really

Hellenism reincarnate.

Our habit of talking about “East” and “West” as

if these were two species of men whose distinctive qualities were derived from

their geographical position, tends to obscure the real facts from us. The West

has by no means been always “Western.” Before the Hellenic culture came into

existence the tribal system went on for unknown ages in Europe, with no

essential difference from the tribal system as it went on, and still goes on,

in Asia. Then, in the East, the tendencies which promoted larger combinations

led to monarchy, as the only principle on which such combinations could be

formed. Asia showed its free tribes and its despotic kingdoms as the only two

types of association. The peoples of South Europe seemed for a time to have

escaped this dilemma, to have established a third type. The third type, indeed,

subsisted for a while, and generated the Hellenic spirit; but the city-state

proved after all too small. These peoples had in the end to accept monarchy.

And the result was the same in Europe as it had been in Asia. If before the

rise of Hellenism, Europe had resembled the Asia of the free tribes, under the

later Roman Empire it resembled the Asia which popular thought connects with

the term “Oriental,” the Asia of the despotic monarchies. The type of character

produced by monarchy was in both continents the same. In Greece and Italy under