|

MEDIEVAL HISTORY LIBRARY

THE LEVANT

A HISTORY OF

FRANKISH GREECE

(1204-1566)

WILLIAM MILLER

CHAPTERS

PDF-The History of the Maritime Wars of the Turks

PDF. THE HISTORY OF THE ISLAND OF CORFU

PREFACE

PROFESSOR Krumbacher says in his History of Byzantine Literature, that, when he announced his

intention of devoting himself to that subject, one of his classical friends

solemnly remonstrated with him, on the ground that there could be nothing of

interest in a period when the Greek preposition cnro governed the accusative

instead of the genitive case. I am afraid that many people are of the opinion

of that orthodox grammarian. There has long prevailed in some quarters an idea

that, from the time of the Roman Conquest in 146 B.C. to the day when

Archbishop Germanos raised the standard of Independence at Kalavryta in 1821,

the annals of Greece were practically a blank, and that that country thus

enjoyed for nearly twenty centuries that form of happiness which consists in

having no history. Forty years ago there was, perhaps, some excuse for this

theory: but the case is very different now. The great cemeteries of mediaeval

Greece, I mean the Archives of Venice, Naples, Palermo, and Barcelona—have

given up their dead. We know now, year by year, yes, almost month by month—the

vicissitudes of Hellas under her Frankish masters, and all that is required now

is to breathe life into the dry bones, and bring upon the stage in flesh and

blood that picturesque and motley crowd of Burgundian, Flemish, and Lombard

nobles, German knights, rough soldiers of fortune from Cataluña and Navarre,

Florentine financiers, Neapolitan courtiers, shrewd Venetian and Genoese

merchant princes, and last but not least, the bevy of high-born dames, sprung

from the oldest families of France, who make up, together with the Greek

archons and the Greek serfs, the persons of the romantic drama of which Greece

was the theatre for 250 years. The present volume is an attempt to accomplish

that delightful but difficult task.

Throughout I have based the narrative upon first-hand

authorities. I can conscientiously say that I have consulted all the printed

books known to me in Greek, Italian, Spanish, French, German, English, and

Latin, which deal in any way with the subject; and I have endeavoured to focus

all the scattered notices concerning the Frankish period which have appeared in

periodical literature, and in the documents of the epoch which have been

published. These I have supplemented by further research in the archives of

Rome and Venice. My aim has been to present as'complete an account as is

possible in the existing state of our knowledge of this most fascinating stage

in the life of Greece. I have also visited all the chief castles and sites

connected with the Frankish period, believing that before a writer can hope to

make the Franks live on paper, he must see where they lived in the flesh.

Enormous as is the debt which every student of mediaeval Greek history owes to

the late Karl Hopf, it was here that he failed, and it was hence that his

Frankish barons are labelled skeletons in a vast, cold museum, instead of human

beings of like passions with ourselves.

One word as to the arrangement of the book. The

historian of Frankish Greece is confronted at the outset with the problem of

telling his tale in the clearest possible manner. He may describe, like Finlay,

the history of each small state separately—a course which not only involves

repetition, but prevents the reader from obtaining a view of the country as a

whole; or he may, like Hopf, combine the separate narratives in one—a policy

which inevitably leads to confusion. I have adopted an intermediate course. The

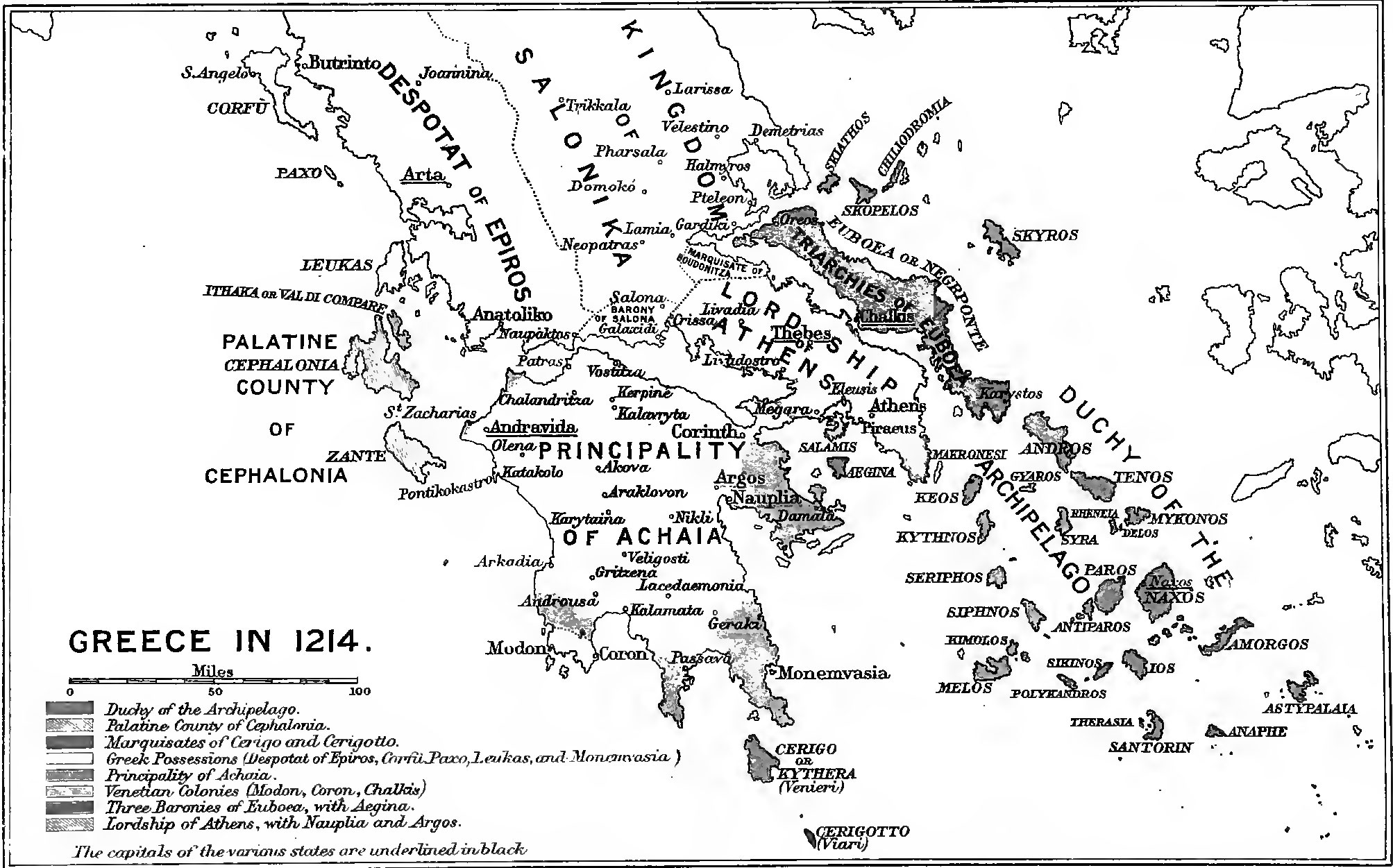

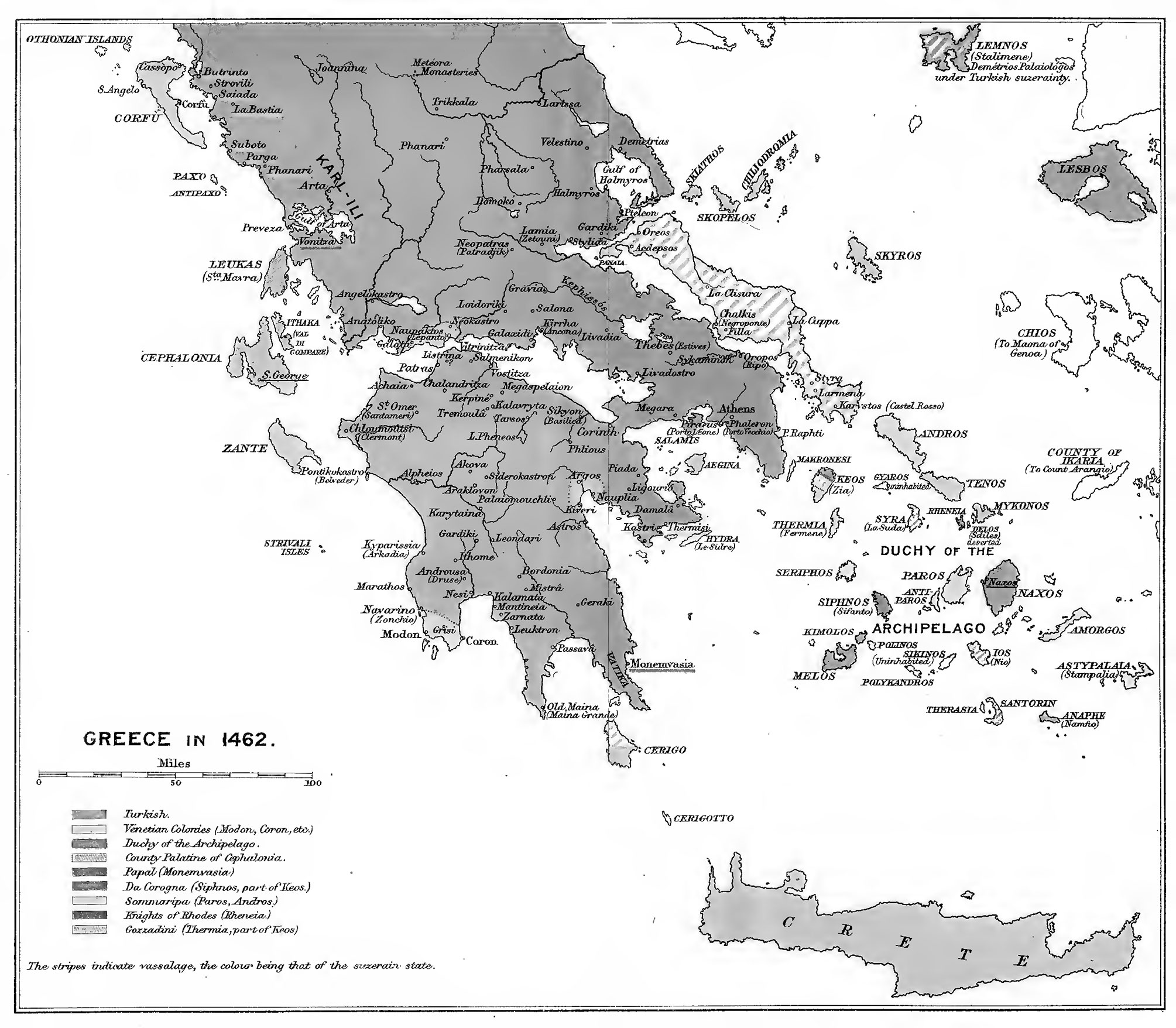

three states of the Morea and continental Greece—the principality of Achaia,

the duchy of Athens, and the Despotat of Epiros—were so closely connected as to

form a fairly homogeneous whole; and with them naturally go the island county

of Cephalonia and the island of Euboea. The duchy of the Archipelago and the

Venetian colony of Corfu, on the other hand, form separate sections, for their

evolution differed widely from the other states. I have therefore treated them

apart. Crete I have omitted for two reasons: it is not yet a part of the Greek

kingdom, and it so happens that Frankish Greece almost exactly coincided with

the area of modern Greece; moreover, the history of Venetian Crete cannot be

written till the eighty-seven volumes of the “Duca di Candia” documents at

Venice are published.

I owe thanks to many friends for help and advice,

especially to K. A. M. Idromenos of Corfu.

W. M.

ROME, December 1907.

|

|